Concise Synthesis of (+)-β- and γ-Apopicropodophyllins, and Dehydrodesoxypodophyllotoxin

Abstract

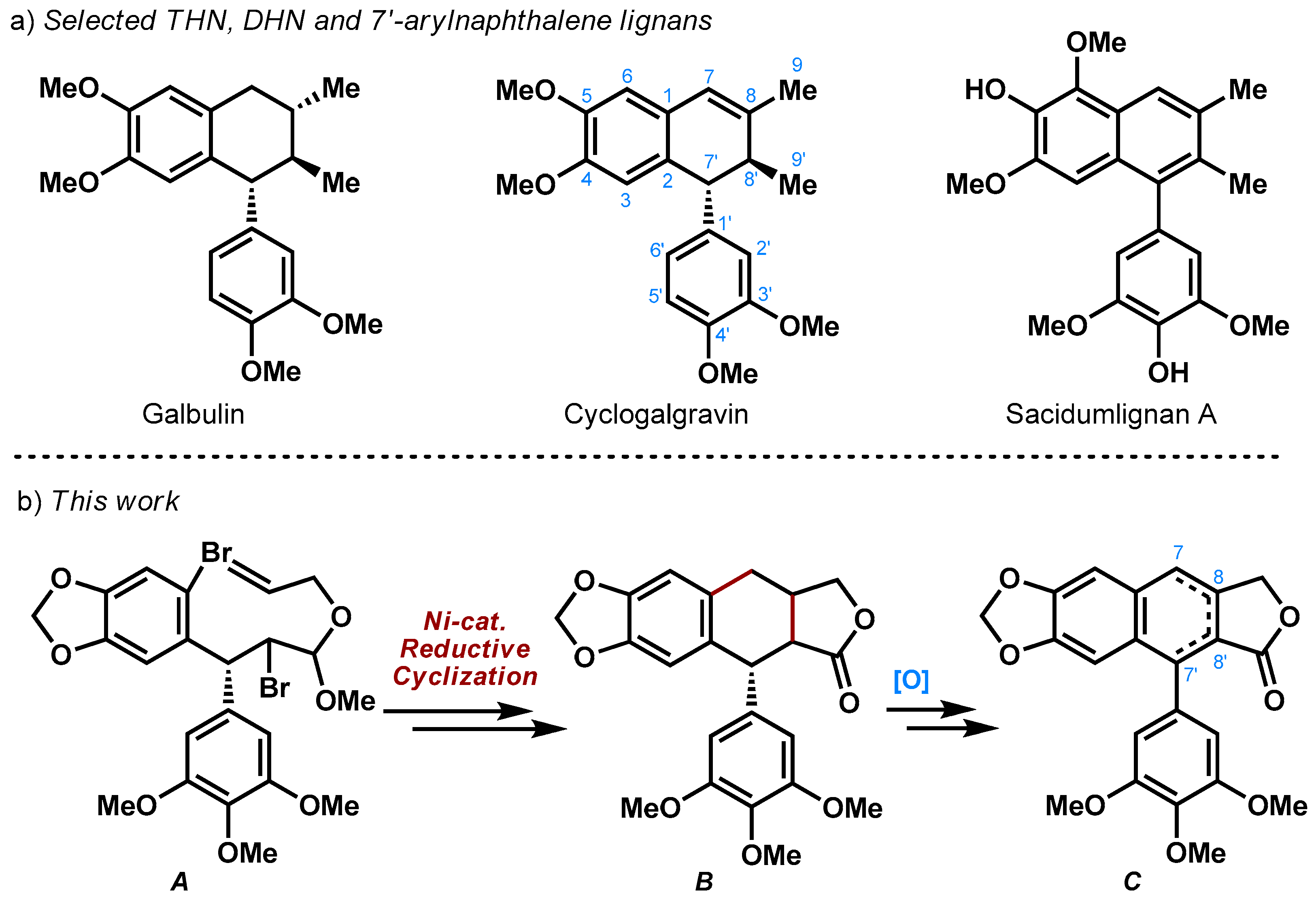

:1. Introduction

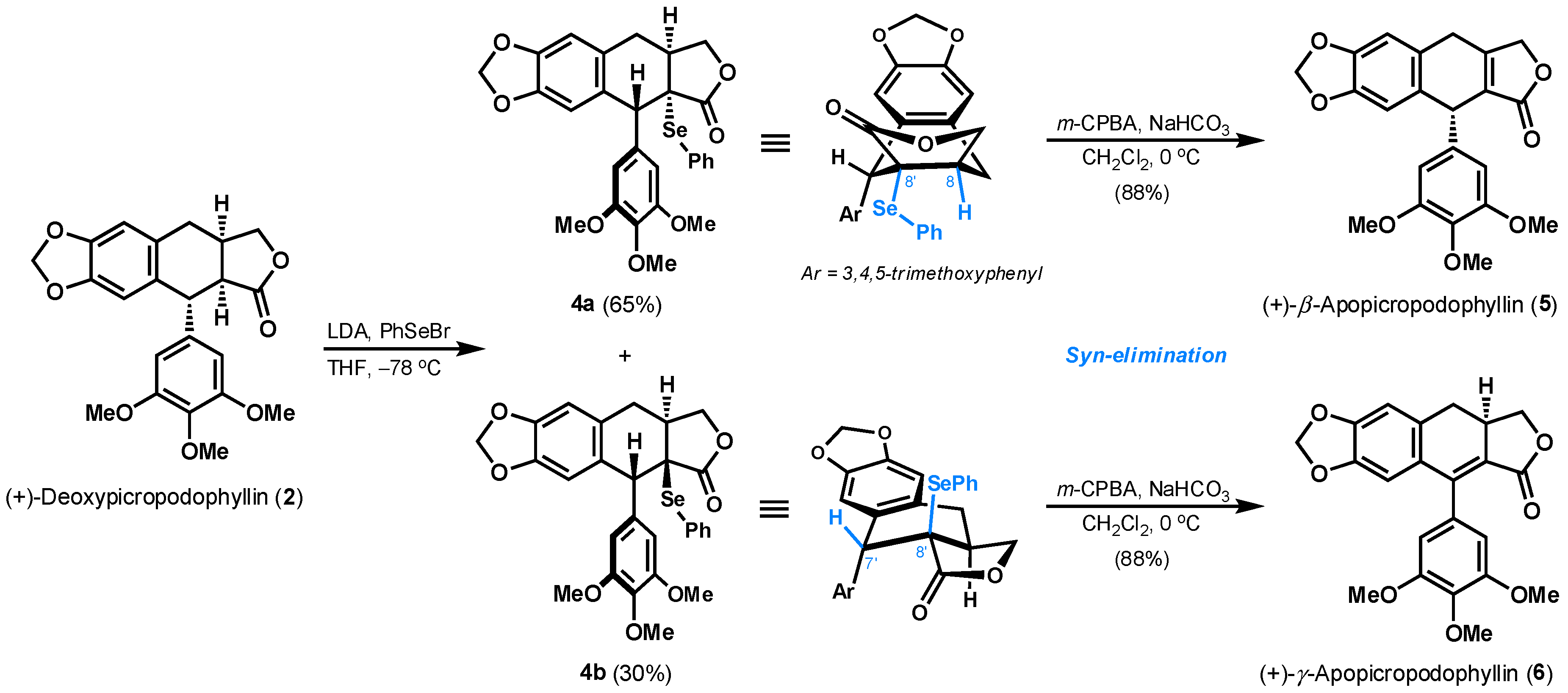

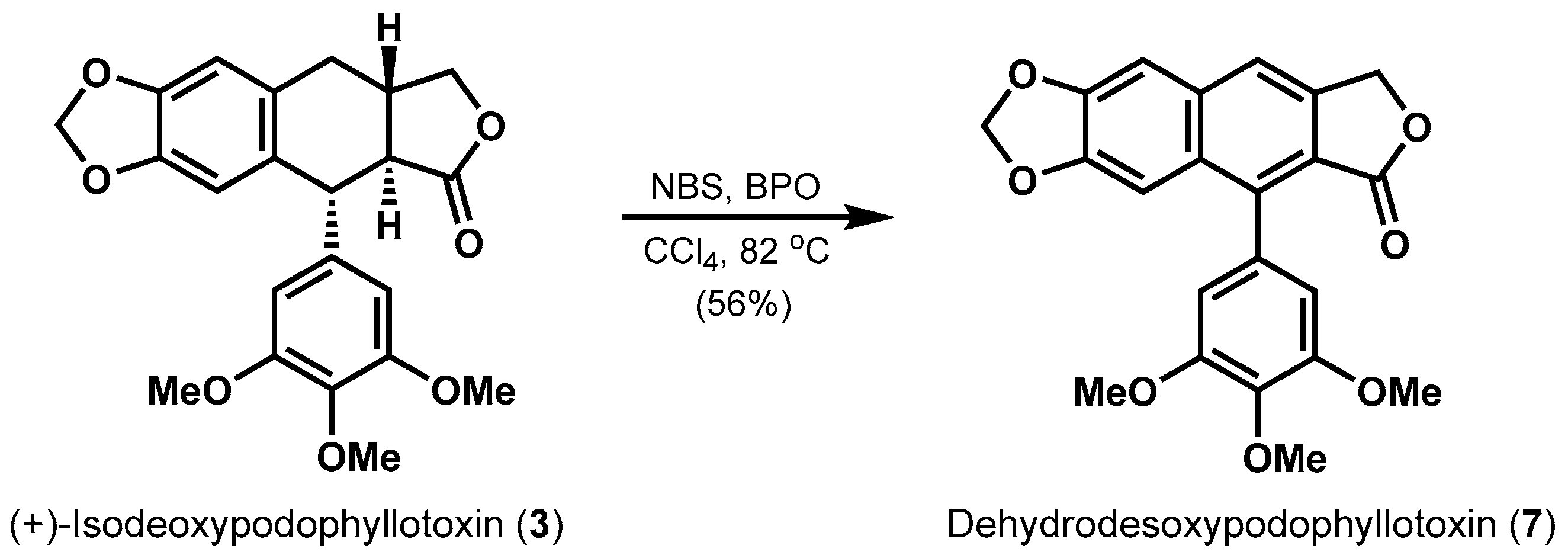

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Procedure

3.2. Synthesis of C9a-PhSe-Deoxypicropodophyllin (4a and 4b)

3.3. Synthesis of (+)-β-Apopicropodophyllin (5)

3.4. Synthesis of (+)-γ-Apopicropodophyllin (6)

3.5. Synthesis of Dehydrodesoxypodophyllotoxin (7)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayres, D.C.; Loike, J.D. Lignans, Chemical, Biological and Clinical Properties; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J. Lignans Chemistry, 1st ed.; Chemical Industrial Press: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 1–395. ISBN 978-7-122-06559-9. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. Lignans, lignins, and resveratrols. In From Biosynthesis to Total Synthesis: Strategies and Tactics for Natural Products; Zografos, A.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 331–379. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, J.D.; Steel, P.G. Advances in the synthesis of aryltetralin lignan lactones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 3815–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.C.; Hsu, C.S.; Lee, G.H. Enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-galbulin via organocatalytic domino Michael-Michael-aldol condensation. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2385–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rye, C.E.; Barker, D. Asymmetric synthesis of (+)-galbelgin, (−)-kadangustin J, (−)-cyclogalgravin and (−)-pycnanthulignenes A and B, three structurally distinct lignan classes, using a common chiral precursor. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6636–6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Route, J.K.; Ramana, C.V. Total synthesis of (−)-sacidumlignans B and D. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.J.; Yan, C.S.; Peng, Y.; Luo, Z.B.; Xu, X.B.; Wang, Y.W. Total synthesis of (±)-sacidumlignans D and A through Ueno-Stork radical cyclization reaction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 2498–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Luo, Z.B.; Zhang, J.J.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.W. Collective synthesis of several 2,7′-cyclolignans and their correlation by chemical transformations. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 7574–7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocsis, L.S.; Brummond, K.M. Intramolecular Dehydro-Diels–Alder Reaction Affords Selective Entry to Arylnaphthalene or Aryldihydronaphthalene Lignans. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4158–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Cong, X.W.; Yang, G.Z.; Wang, Y.W.; Peng, Y. Divergent asymmetric syntheses of podophyllotoxin and related family members via stereoselective reductive Ni-catalysis. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1651–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Cong, X.W.; Yang, G.Z.; Wang, Y.W.; Peng, Y. Stereoselective synthesis of podophyllum lignans core by intramolecular reductive nickel-catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2040–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.S.; Peng, Y.; Xu, X.B.; Wang, Y.W. Nickel-mediated inter- and intramolecular reductive cross-coupling of unactivated alkyl bromides and aryl iodides at room temperature. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6039–6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, Y.W.; Peng, Y. Nickel-mediated inter- and intramolecular C-S coupling of thiols and thioacetates with aryl iodides at room temperature. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Luo, L.; Yan, C.S.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, Y.W. Ni-catalyzed reductive homocoupling of unactivated alkyl bromides at room temperature and its synthetic application. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10960–10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Xu, X.B.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.W. Nickel-mediated stereocontrolled synthesis of spiroketals via tandem cyclization-coupling of β-bromo ketals and aryl iodides. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 472–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, J.J.; Ling, W.J.; Shao, Y.L.; Wang, Y.W.; Peng, Y. Unified synthesis of (−)-folicanthine and (−)-ditryptophenaline enabled by a nickel-mediated reductive dimerization at room temperature. Synthesis 2014, 46, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xu, X.B.; Duan, S.M.; Ren, L.; Shao, Y.L.; Wang, Y.W. Stereospecific synthesis of tetrahydronaphtho[2,3-b]furans enabled by a nickel-promoted tandem reductive cyclization. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5170–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.W.; Peng, Y. Nickel-promoted reductive cyclization cascade: A short synthesis of a new aromatic strigolactone analogue. Synthesis 2017, 49, 3576–3581. [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama, M.; Kimura, Y.; Ohta, A. Stereoselective total syntheses of (±)-arthrinone and related natural compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 10013–10017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.Q.; Yang, L.; Feng, G. Podophyllotoxin derivatives show activity against Brontispa longissima larvae. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kennedy-Smith, J.J.; Young, L.A.; Toste, F.D. Rhenium-catalyzed aromatic propargylation. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1325–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, R.C.; Teague, S.J.; Meyers, A.I. Asymmetric total synthesis of (−)-podophyllotoxin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 7854–7858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCDC-1875746 (5) Contain the Supplementary Crystallographic Data for This Paper. These Data Can Be Obtained Free of Charge. Available online: http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Kashima, T.; Tanoguchi, M.; Arimoto, M.; Yamaguchi, H. Studies on the constituents of the seeds of Hernandia ovigera L. VIII. Synthesis of (±)-desoxypodophyllotoxin and (±)-β-peltatin-A methyl ether. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991, 39, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Arimoto, M.; Nakajima, S.; Tanoguchi, M.; Fukada, Y. Studies on the constituents of the seeds of Hernandia ovigera L.V. Syntheses of epipodophyllotoxin and podophyllotoxin from desoxypodophyllotoxin. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1986, 34, 2056–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Asano, H.; Wakasugi, K.; Morita, J.-I.; Aso, Y.; Yoshida, E.; Motoyoshiya, J.; Aoyama, H.; Tanabe, Y. Regiocontrolled benzannulation of diaryl(gem-dichlorocyclopropyl)methanols for the synthesis of unsymmetrically substituted α-arylnaphthalenes: Application to total synthesis of natural lignan lactones. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 2667–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrecker, A.W.; Hartwell, J.L. Components of podophyllin. IX. The structure of apopicropodophyllins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 5676–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, J.; Nan, G.; Wang, Y.-W.; Peng, Y. Concise Synthesis of (+)-β- and γ-Apopicropodophyllins, and Dehydrodesoxypodophyllotoxin. Molecules 2018, 23, 3037. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23113037

Xiao J, Nan G, Wang Y-W, Peng Y. Concise Synthesis of (+)-β- and γ-Apopicropodophyllins, and Dehydrodesoxypodophyllotoxin. Molecules. 2018; 23(11):3037. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23113037

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Jian, Guangming Nan, Ya-Wen Wang, and Yu Peng. 2018. "Concise Synthesis of (+)-β- and γ-Apopicropodophyllins, and Dehydrodesoxypodophyllotoxin" Molecules 23, no. 11: 3037. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23113037