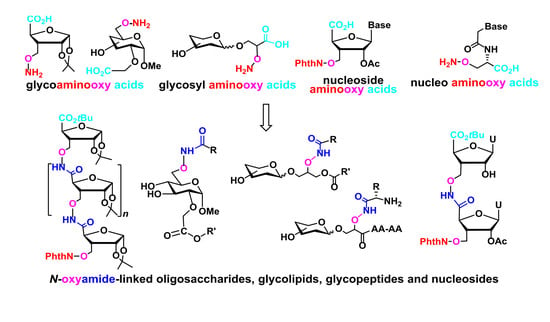

1. Introduction

The high nucleophilicity of hydroxylamine derivatives as well as the unique structural and chemical properties of the N-O, oxime and

N-oxyamide bonds have triggered the

O-amino functionalization of biomolecules like peptides, proteins, carbohydrates, nucleosides and nucleotides. Due to repulsion between the lone pairs of the electron of the nitrogen and oxygen atoms, the N-O bond of hydroxylamine derivatives has unusual conformational properties, which have been exploited to obtain particular N-O turn structures in aminooxy acid-derived peptides for the preparation of new foldamers, anion receptors or channels [

1,

2]. The N-O bond is relatively sensitive to radical conditions because of the low N-O bond dissociation energy [

3]. Oximes show higher hydrolytic stability than hydrazones [

4], while the

N-oxyamide linkage is resistant to chemical hydrolysis [

1]. Aminooxylated carbohydrates and glycoconjugates are attracting the increasing interest for the understanding of the glycobiology and for diverse biomedical applications [

3,

5].

N-,

O-glycosyl hydroxylamines as well as

N-hydroxyamino and

O-amino sugars have been developed over the last twenty years. Various chemically modified oligonucleotides have also been reported, with an increasing number showing up as drug candidates for oligonucleotide therapies [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Among them,

O-amino nucleosides have been prepared for the development of human UDP-GlcNAc 4-epimerase inhibitors [

10], modified oligonucleotides [

11] or for next generation sequencing [

12]. N-O,

N-oxyamide or

N-alkoxycarbamate-linked oligonucleotides have also been synthesized as oligonucleotides mimics [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The focus of this article is to summarize our own efforts in the preparation of

O-amino sugar and nucleoside derivatives, including sugar aminooxy acids, glycosyl α-aminooxy acids,

O-aminooxy nucleosides and nucleo-aminooxy acids for the generation of

N-oxyamide-linked oligosaccharides, glycopeptides, glycolipids, and oligonucleoside mimics.

2. Sugar Aminooxy Acids for Oligosaccharide Mimics

The design and synthesis of novel molecules bearing different functions are of great interest for organic, bioorganic, medicinal as well as material chemistry. The creation of cleverly functionalized molecules has a large impact in designing bioactive molecules and for drug discovery. Apart from their biological involvement, carbohydrates are readily available chiral compounds which have been widely used in organic synthesis. We have decided to introduce both aminooxyl and carboxyl functions on the sugar pyranosidic or furanosidic skeletons to generate sugar aminooxy acids or glycoaminooxy acids as multifunctional building blocks which could be used for the synthesis of novel

N-oxyamide linked oligosaccharides or glycoconjugates with interesting structural properties. It has been shown that

N-oxyamide-linked peptides can easily form intramolecular hydrogen bonds to facilitate turns and helical structures [

1,

2]. A rigid ribbon-like secondary structure has been observed on a trimer of a

cis-β-furanosidic sugar aminooxy acid by the group of Chandrasekhar [

18]. Nanorod formation through intermolecular H-bonding has also been observed on a symmetric cyclotetrapeptide prepared from a 2-(

C-furanosyl) β-amino acid and an α-aminooxy acid [

19]. Besides, the

N-oxyamide-linkage is resistant to chemical and enzymatic hydrolysis [

20], and

N-oxyamide bonds could be readily formed using classical amide formation methods.

We have synthesized

d-ribofuranosidic glycoaminooxy acid

4 from diisopropylidene

d-glucose (

1,

Scheme 1) [

21]. Since initial efforts to introduce an aminooxyl group at the 3-position of

1 failed, probably due to the steric hindrance, we converted

1 into its homologue

2 through Collins oxidation, Wittig reaction, and hydroboration-hydroxylation reactions. Unlike the secondary alcohol function in

1, the primary alcohol function in

2 reacted efficiently under Mitsunobu conditions with

N-hydroxyphthalimide to give

3 after selective deprotection of the 5,6-

O-isopropylidene moiety. Oxidative cleavage of the diol, followed by oxidation of the resulting aldehyde, afforded the desired phthalimidooxyl acid

4 which can be readily converted into aminooxy ester

5.

The building blocks

4 and

5 were coupled to form oligomers from di- to hexamers (

Scheme 2). For the synthesis of oligomers with more than three sugar units, the

tBu group was selectively removed using 13.7% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in CH

2Cl

2 without affecting the acetonide protecting groups.

N-Oxyamide bond formation can be realized by using

N-ethyl-

N’-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC)/1-hydroxy benzotriazole (HOBt) method or two organophosphorous reagents diphenylphosphoryl azide (DPPA)/

N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA)/NaHCO

3 and diethyl cyanophosphonate (DEPC)/Et

3N in similar yields.

Concerning pyranosidic glycoaminooxy acids, we have firstly prepared the compound

14 bearing the carboxylic acid on the

C-glycosidic anomeric chain (

Scheme 3) [

22]. This compound could be easily prepared from the readily available

C-allyl glucoside

13 containing a free hydroxyl group at the C-6 position [

23]. Hence, compound

13 was converted to the phthaloyl-protected glycoaminooxy acid

14 in two steps involving Mitsunobu reaction with PhthNOH, followed by oxidation of the alkene moiety to a carboxylic acid. The compound

14 was further transformed into the building block

15 via protection of the carboxylic acid as a

tBu-ester followed by the removal of the phthaloyl group to afford the free oxyamine. To demonstrate the synthetic utility of the building blocks

14 and

15 in the preparation of oligosaccharide and glycopeptide mimetics, compound

15 was coupled with

14 or Boc-Gly-OH to give the disaccharide

16 or glycosyl amino acid

17 in good yield.

The pyranosidic glycoaminooxy acid building blocks bearing the aminooxyl and carboxylic groups on the 2,6-positions were prepared from the

d-glucopyranoside

18 (

Scheme 4) [

24]. Alkylation of the hydroxyl group with BrCH

2CO

2tBu followed by acidic hydrolysis of the

tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBS) group and conversion of the resultant hydroxyl to phthalimidooxyl group afforded the fully protected glycoaminooxy acid

19. Selective removal of the

tBu group using TFA in CH

2Cl

2 formed the building block

20 bearing a free carboxylic acid. On the other hand, the phthaloyl group was removed through hydrazinolysis to the building block

21. The two orthogonally protected glycoaminooxy acid units were employed for the preparation of oligomers from dimer

22 to tetramer

24.

From our results and those reported in the literature [

3,

5], we can conclude that oligomers derived from sugar aminooxy acids can be obtained as efficiently as those formed from the previously developed sugar amino acid building blocks [

25,

26,

27]. However, benzyl protecting groups are to be avoided due to the sensitivity of the N-O bond towards the benzyl-deprotecting hydrogenolysis conditions [

3].

We then decided to use acid-sensitive

para-methoxybenzyl groups (

Scheme 5) [

28]. First, methyl α-

d-glucopyranoside was selectively protected with TBS and

para-methoxybenzyl (PMB) groups to

25 and

26. Contrary to compound

18, the 2-

O-alkylation of

26 has necessitated the optimization of the reaction conditions due to the very low conversion. The best conversion (64%) was obtained by slow addition of BrCH

2CO

2Et after formation of the alcoolate. The phthalimidooxyl group has been introduced under Mitsunobu conditions after desilylation, leading to the PMB-protected glycoaminooxy ester

28. The efficient deprotection of the PMB has been demonstrated in the corresponding glycolipids mimics (vide infra).

3. Glycosyl α-Aminooxy Acid Derivatives

Glycosyl amino acids are constituents of glycopeptides and glycoproteins playing key roles in biological processes. We have synthesized

C- and

O-glycosyl aminooxy acid derivatives as novel glycosyl amino acid building blocks for the generation of glycopeptide mimics. The α-

C-glycosyl aminooxy acid derivatives can be readily prepared from α-

C-allyl glucosides

29 and

30, through dihydroxylation, selective tritylation, Mitsunobu reaction with PhthNOH, detritylation and oxidation [

29] (

Scheme 6). Both α-

C-glucosyl

l- and

d-α-aminooxy esters

35–

38 have been successfully synthesized.

For the

O-glycosyl aminooxy acid derivatives, we have stereoselectively synthesized both (2

R)- and (2

S)-aminooxy analogues of β-

O-glucosylserine from

sn-(3-β-

O-glucosyl)glycerol

39 which was obtained through glycosylation of

sn-1,2-di-

O-benzyl-glycerol with

d-glucose pentaacetate followed by debenzylation (

Scheme 7) [

30]. Selective silylation and Mitsunobu reaction with PhthNOH and acidic desilylation afforded the

sn-(2-

O-phthalimido-1-

O-glucosyl)glycerol

41 which was transformed into the (2

R)-3-β-

O-glycosyl aminooxy ester

42 after selective deprotection of phthaloyl group with 1.1 equivalent of hydrazine in methanol during 20 min at 0 °C. To prepare the (2

S)-isomer, the configuration of the secondary alcohol was inverted via triflation followed by reaction with NaNO

2 (Lattrell-Dax epimerization method). The resulting alcohol

43 was converted to (2

S)-β-

O-glucopyranosylaminooxyl ester

45 by following the same synthetic sequence employed for the (2

R)-stereoisomer.

With a reliable method to both stereoisomers of the β-

O-glucosylserine analogues in hand, the synthesis of

N-oxyamide-linked glycopeptides was investigated (

Scheme 8). The glucosyl tripeptide mimetic

46 was prepared from

42 after coupling with FmocGlyOH, deprotection of the

tBu group, and coupling with GlyO

tBu. The

O-amino function can also be protected with Fmoc group and the corresponding glycopeptide

47 could be further used in the solid-phase peptide synthesis. Interestingly, NMR and IR studies suggested that compound

46 formed an α N-O turn structure via an eight-membered-ring intramolecular H bond between the amide NH and the carbonyl group of the

N-oxyamide.

4. N-Oxyamide-Linked Glycolipids

As part of the glycoconjugate family, glycolipids are implicated in a variety of important biological phenomena such as cell-cell interactions, viral and bacterial infections, immune responses, signal transduction, cell proliferation, etc. Natural glycolipids like glycoglycerolipids (GGLs) and glycosphingolipids (GSLs), as well as their synthetic mimics, have also shown very interesting biological activities [

31,

32]. The design of glycolipid mimics has become a useful strategy in drug discovery. We have prepared

N-oxyamide-linked glycolipids as mimics of glycoglycerolipids and glycosphingolipids by replacing the ester group in GGL with a

N-oxyamide functionality [

33,

34]. The β-glucolipids bearing two lipid chains

53–

57 were synthesized from the

O-phthaloylamino β-glucoglycerol

41, by esterification with palmitic acid, removal of the phthaloyl group and coupling with different carboxylic acids so as to introduce a lipid chain onto the nitrogen atom, and final full deprotection with hydrazine (

Scheme 9). Three β-glucolipids bearing one lipid chains

61–

63 have also been obtained from

40. Coupling of octanoic acid with the glucosyl aminooxy ester

42 led to glucolipid

64 [

30].

Synthesis of galactoglycerolipids

73–

77 has been realized from D-galactose pentaacetate in a similar way as the gluco-derivatives (

Scheme 10) [

34]. Interestingly, deacetylation of

68 and

69 under Zemplén conditions gave the intramolecular transacylation products

78 and

79, while the compound

71 led to the galactolipid

80. The synthesized glycolipids bearing one and two palmitic acyl chains

56,

62,

76 and

80 are able to assemble with polyethyleneglycol (PEG) thiol-coated gold nanoparticles to form a new type of glyco-Au nanoparticle (AuNP) capable of receptor-targeting cell imaging and drug delivery. The galactolipids derived galacto-AuNPs are selective to galactose-selective peanut agglutinin (PNA), while the gluco-AuNPs selective for concanavalin A (Con A). The efficiency of

76-AuNP for receptor-targeting hepatocellular imaging of human liver cancer Hep-G2 and the anticancer drug hydrocamptothecin delivery has been demonstrated.

Glycolipids bearing lipid chains on the 2,6-positions of methyl α-

d-glucopyranoside have been prepared from the 3,4-di-

O-PMB protected derivatives

26 and

28 (

Scheme 11) [

28]. Glycolipid

82 is readily obtained from the sugar phthalimidooxy ester

28 after successive deprotection, coupling reactions. The PMB group can be removed by 5% TFA in dichloromethane. Compound

82 is also accessible from

26 after careful 2-

O-alkylation, followed by usual coupling, deprotection and Mitsunobu reactions. From

26, we have also prepared glycolipid

85 bearing a 2-

O-palmitate.

5. O-Aminooxy Nucleosides

We have designed nucleoside aminooxy acids as novel building blocks for the development of stable oligonucleotide mimetics [

35]. Replacement of the ionic phosphodiester by the neutral

N-oxyamide linkage would not only increase its cellular permeability but also enhance its resistance to extra- and intracellular nucleases degradation. Synthesis of modified RNA oligomers has attracted renewed interest since the discovery of small interfering RNA (siRNA) for gene regulation [

6]. We are particularly interested in the development of ribonucleoside aminooxy acid which could be further used for the generation of

N-oxyamide-linked oligoribonucleosides. From the previously prepared furanosidic glycoaminooxy acid

4, five nucleoside aminooxy acids

86–

90 have been synthesized through

N-glycosylation in the presence of

N,

O-

bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA) and trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf) after acidic hydrolysis of the acetonide and acetylation of the resulting hydroxyl groups (

Scheme 12). Uridine derivative

86 was chosen for the investigation for

N-oxyamide-linked oligomer formation. Treatment with the

tert-butoxytrichloroacetimidate led to the formation of the desired

tBu ester

92 along with compound

91 bearing an extra

tBu group on the nitrogen atom of the uracil moiety. Compound

91 could be converted to

92 using 10% AcOH in CH

2Cl

2. Hydrazinolysis of

92 led to the removal of both phthaloyl and acetyl group to

94, along with a small amount of transacetylation product

93. The oxyamine can be further protected with Fmoc group (

95). Boc protected

N-methyl nucleoside aminooxy ester

96 can also be prepared from

86. Coupling of the building blocks

86 and

94 led to the

N-oxyamide-linked dinucleoside

97. We have observed the formation of the methanolysis product

98 during the column chromatography with CH

2Cl

2/MeOH as eluent.

We then decided to investigate the stability of uridine derivative

86 in the presence of MeOH (

Scheme 13). Treatment of

86 with K

2CO

3 in MeOH at room temperature led to the ring-opening product

99 in 30% isolated yield. Esterification of

86 in DMF led quantitatively to the methyl ester

100. Subsequent deacetylation with NaOMe led firstly to the phthalimido ring-opening product

101 which can be converted back to

100 by heating at 130–140 °C under reduced pressure. Further reaction with NaOMe deprotected the 2’-

O-acetyl group, providing a mixture of compounds

102 and

103. Similar phenomena have been observed during the saponification of

100 with K

2CO

3 or NaOH (4M) in MeOH. The ring closure reaction of the phthalimido group can be achieved by heating

102 under reduced pressure. Under acidic condition in MeOH, we have observed successive transformations of compound

86 to the methyl ester

103 through the intermediates

100 to

102 on thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

From the diacetone

d-glucose

1, nucleoside aminooxy esters

106–

108 bearing phthalimidooxyl group on 5’-position have been prepared according to the

Scheme 14 [

36]. Compound

1 was first converted to allylic ester

104. Mitsunobu reaction of

104 with PhthNOH led to impure

105 which was then prepared through the mesylate intermediate followed by nucleophilic substitution reaction.

N-glycosylation in the same conditions as for

4 led to the target nucleosides

106–

108.

From the uridine, we have prepared the uridine aminooxy esters through selective 2’,5’-di-

O-silylation, oxidation of 2’-OH followed by Wittig reaction and hydrogenation under acidic condition to give stereoselectively the ester

109 (

Scheme 15) [

36]. However, all temptations to introduce the phthalimidooxyl function on 5’-position through the Mitsunobu reaction failed. Hopefully, the 5’-hydroxyl function can be converted to Boc- or phthaloyl protected

110 and

111 through iodide intermediate, then deprotected to oxyamine nucleoside

112. Unfortunately, deprotection of the ester groups in

110 and

111 led to degradation, making further formation of

N-oxyamide-linked nucleoside aminooxy acid dimers impossible. We have also tried to protect the oxyamine in

112 with a 4-pentenoyl (Pen) group. Once again, decomposition was observed during the saponification or removal of the Pen-protecting group with I

2 [

37].

N-O-linked thymidine dimers were prepared from commercially available thymidine derivatives through introduction of an aminooxyl function on the 5’-position in

115 and an aldehyde or carboxylic functions on 2’ in

113 and

114 (

Scheme 16) [

38]. Coupling of

114 with

115 led to the

N-oxyamide-linked dithymidine

116, while condensation of aldehyde

113 with oxyamine

115 gave the oxime linked dimer

117 as a mixture of

E and

Z isomers (3:2) which can be reduced to the oxyamine-linked dinucleoside

118.

6. Nucleo-Aminooxy Acids

As promising alternatives to peptide nucleic acids, nucleobase-functionalized peptides have attracted increasing interest because of their well-ordered secondary structures and stability towards enzymatic degradations, as well as their cellular nucleus penetration ability without cytotoxic effects [

39,

40,

41]. We have designed and synthesized α-amino-β-aminooxy acid derivatives bearing nucleobases covalently attached to its α-position through an amide or triazole linkage as novel building blocks of nucleopeptides (

Scheme 17) [

42]. The key aminooxy acid

119 was prepared from

l-Ser-OMe. Coupling reaction with carboxybenzyl (Cbz)-protected cytosin-1-ylacetic acid formed successfully the nucleo-aminooxy ester

120. However, the analogous reaction with thymin-1-ylacetic acid was found to be problematic because of the difficult purification. The phthaloyl group in

119 was then replaced by a Boc group to give

121 via Cbz-protection of the amino group. The Cbz group in

121 should be removed using Pd-catalyzed hydrogenolysis in less than 10 min to avoid reductive cleavage of the N-O bond. The thymidine aminooxy ester

122 was obtained in moderate yield because of the over acylation on the NH-O nitrogen. Improved yields were obtained from the

bis-Boc-protected

123. Subsequently, full deprotection led to the target nucleo-aminooxy acids

126 and

127. Triazole-linked nucleo aminooxy esters

129 and

130 have been prepared from the azido derivative

128, where the use of ascorbic acid instead of sodium ascorbate is essential to avoid the elimination of the phthalimidooxy moiety during the triazole formation.

However, synthesis of the corresponding nucleopeptides was hampered by the rapid elimination reaction of the phthalimidooxyl group to give an acylamidoacrylate derivative during the deprotection of methyl esters in

124,

125,

129 and

130. To avoid this side reaction, we have then decided to prepare nucleo-aminooxy acids based on α-amino-γ-aminooxy ester

132, which can be obtained from

N-Cbz-

l-Met through

S-alkylation with iodoacetamide followed by lactonisation in hot citric acid (

Scheme 18) [

43]. To remove the Cbz protecting group without the cleavage of the N-O bond, 40% Pd/C (

w/

w) was necessary to quickly deprotect the Cbz group. Subsequent coupling with functionalized nucleobases afforded the corresponding nucleo γ-aminooxy esters

133–

136.

As expected, the obtained nucleo γ-aminooxy esters can be saponified to the corresponding carboxylic esters without elimination of the phthalimidooxyl group (

Scheme 19). Coupling reaction with the oxyamine derivatives

139–

141 furnished the

N-oxyamide-linked nucleopeptides

142–

144. Improved coupling yield could be obtained by using DMF as solvent to solubilize the starting materials.