1. Introduction

The detection, extraction, and transport of anions is an important element in a wide range of biological and chemical processes [

1]. Biological evolution has developed a score of anion binding proteins usually with high selectivity. The sulphate-binding protein of Salmonella typhimurium [

2] is an example of one that binds this anion via a number of H-bonds. Another protein is responsible for the binding and transport of phosphate [

3] with very high specificity. Still another protein, present in blue-green algae, is highly specific for the nitrate anion [

4] and another binds specifically to bicarbonate [

5]. While the evolutionary process has developed some very specific and selective anion binding agents, modern technology lags behind. Many receptors make use of general electrostatic interactions and sometimes of H-bonds [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The thiourea molecule, for example, is a widely used [

13,

14,

15] anion binder that takes advantage of its H-bonding capability. The guanidinium cation and its derivatives [

16,

17] have also found use in this regard. However, the anion receptors that have been developed to date still suffer from certain disadvantages. Their selectivity is not optimal and they are unable to detect the presence of a particular anion below a given concentration threshold. Furthermore, at this point in time, the biggest need is the development of highly selective receptors that can function in an aqueous rather than organic or biological environment. “Examples of receptors that are neutral or of low charge and operate in organic–aqueous mixtures are uncommon and those that function in 100% water are rarer still” [

1].

One major advancement in this field arose from the growing recognition of the phenomenon of halogen bonds (XBs) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] where an attractive force occurs between a halogen atom and an electron donor such as the lone pair of an amine. It was not long before researchers applied this concept in order to develop receptors that are highly selective for one anion over another [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The Beer group [

33] found that substitution of H by Br enabled the consequent halogen bond to more effectively bind chloride and that receptors of this type could recognize [

34] both chloride and bromide ions purely by virtue of XBs [

35,

36]. Chudzinski et al. [

37] obtained quantitative estimates of the contribution of halogen bonding to the binding of anions to bipodal receptors and later [

38] applied halogen bonds to develop pre-organized multi-dentate receptors capable of high-affinity anion recognition. Halogen bonding exerts selectivity for bromide over chloride or other anions in a set of tripodal receptors [

39]. Our own group [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46] has applied quantum chemical calculations toward solving this issue, which shows that the replacement of H in a series of H-bonding bidentate receptors by halogen atoms can influence their binding to halides. The work detailed a remarkable enhancement of both binding and selectivity especially when the H atom is replaced by I.

A rapidly burgeoning group of studies has extended the basic concepts of the XB to other atoms in the periodic table. Depending upon the particular family to which the atom in question belongs, these bonds have come to be known as chalcogen and pnicogen bonds [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Given the similarities, it was not surprising that noncovalent bonds of this sort can be every bit as useful as XBs in the context of anion binding and transport, which is being demonstrated in recent work [

61,

62,

63,

64]. Tetrel atoms (C, Si, Ge, Sn, Pb) seem capable of engaging in very similar interactions as well, which is becoming increasingly clear [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Therefore, there is every reason to believe that tetrel bonds might find a place in this constellation of noncovalent bonds that can function as integral components in anion receptors.

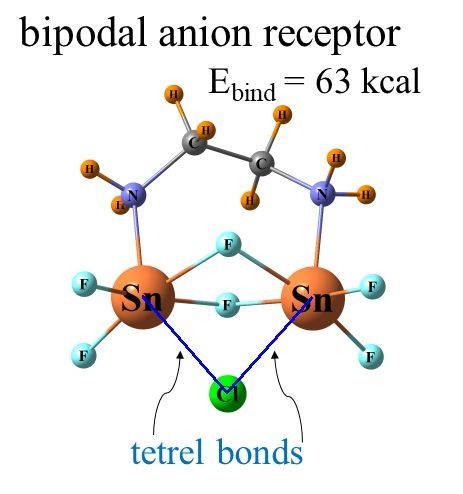

It was just this idea that motivated our group to recently perform calculations to examine how the latter type of bonds might compare with chalcogens in this context. A set of bidentate receptors, modeled closely after those in a prior experimental study, was constructed [

43], which varied in whether the atoms that engaged directly with the anion were chalcogen, pnicogen, or tetrel. The transition from chalcogen to pnicogen to tetrel yielded not only progressively stronger binding to anions but also greater selectivity. In a quantitative sense, the binding energy of halides to a Ge-bonding bidentate receptor was as high as 63 kcal/mol and preferentially bound F

− over other halides with a selectivity of 27 orders of magnitude. These quantities are especially impressive since the receptor was electrically neutral, which forgoes the positive charge on many other such candidates. A follow-up study [

46] delved somewhat more deeply into this issue by adding halogen atoms to the mix as well and by using a different bidentate receptor structure. It was found that with respect to Cl

− and Br

−, the binding is insensitive to the nature of the binding atom, viz H, halogen, chalcogen, or tetrel. However, there is a great deal of differentiation with respect to F

− where the order varies as tetrel > H ~ pnicogen > halogen > chalcogen. The replacement of the various binding atoms by their analogues in the next row of the periodic table enhances the fluoride binding energy by 22% to 56%. The strongest fluoride binding agents utilize the tetrel bonds of the Sn atom while it is I-halogen bonds that are preferred for Cl

− and Br

−.

At this point then, there are sound reasons to believe that tetrel bonding offers a unique opportunity in the design of effective and highly selective receptors. However, there are a number of very important issues that remain to be resolved. In the first place, most of the prior calculations have been centered in the gas phase while it is in solution, especially in water, there is more urgent need for these receptors. Particularly when one is dealing with charged species, the effects of hydration can be expected to be especially strong, so in vacuo trends cannot be simply transferred to water but must be assessed directly. For example, hydration would stabilize the receptor/anion complex but would more heavily stabilize the separate individually charged species. Therefore, gas-phase trends may be radically different in water. It is for this reason that the calculations reported in this study are conducted in an aqueous environment.

Within the realm of tetrel bonds, there is a question as to which tetrel (T) atom would be most effective. Past work has suggested that tetrel bonding is strengthened when the T atom is enlarged, but this phenomenon relates to the gas phase and has not been thoroughly tested in water. The same question pertains to the finding that tetrel bonding is enhanced by electron-withdrawing substituents. How might the strength of tetrel bonding be affected if the tetravalent -TH3 group is perfluorinated in water or likewise if the group possesses a positive charge? In a similar vein, most of the bipodal receptors that have come under experimental scrutiny are dications so it is important to assess how a double positive charge affects the binding. Within the context of the construction of the full receptor, the binding group has typically been placed by experimentalists on an imidazolium or triazolium group. Calculations can be used to compare and contrast a wider range of different groups and consider whether the aromaticity of this group is important or whether it even needs to be cyclic. One can address specificity by comparing the binding energetics of a number of various anions to each candidate tetrel-binding receptor. Lastly, since the extraction of an anion from solution by any receptor must overcome the attraction of this anion to counter-ions, this competition must be considered as well.

2. Systems and Methods

In the first set of tests, tetrel T atoms examined included the full {Si, Ge, Sn, Pb} set. These were placed into both a -TH

3 setting and its perfluorinated -TF

3 counterpart. One of the most commonly used groups to which anion-binding agents have been attached in the past is the imidazole species [

9,

27,

33,

34,

39,

42,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78] so it is this group that is considered in the pilot set of calculations. Both TH

3 and TF

3 were, therefore, affixed to an imidazole moiety and comparisons were made to the same system after protonation of the ring to an imidazolium group. The primary anion used to test binding was Cl

−, which is representative of the entire halide set without the complications noted earlier for the smaller F

−, which was prone to engage in asymmetric covalent bonding with the receptor. Another reason for selecting chloride as the prototype anion is the close correspondence observed recently [

79] between its calculated binding energy with a series of Lewis acids and the experimental trends arising from NMR measurements. Since this first battery of tests pointed to Sn as the most effective tetrel-bonding atom, it was the focus of the next testbed of calculations, which evaluated a wide range of groups that might replace imidazolium and perhaps enhance the anion binding. These replacements included both aromatic and nonaromatic, cyclic and noncyclic, and both mono and dictations. Having established one or two prime candidates, calculations then turned to comparisons between different anions of chemical and biochemical importance including all four halides, OH

−, NO

3−, and HCO

3−. Since the receptor must be capable of pulling the anion of choice out of solution where it is closely associated with positive counter-ions, the receptor/anion binding was compared to that with K

+ cations as model counter-ions.

Calculations were carried out with the Gaussian-09 [

80] set of programs. The M06-2X DFT functional [

81] was used along with the aug-cc-pVDZ basis set. For the heavy atoms I, Pb, and Sn. The aug-cc-pVDZ-PP pseudopotential was taken from the EMSL library [

82,

83] so as to incorporate relativistic effects. This level of theory is appropriate for this task as evident by previous work by others [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89] as well as by ourselves in dealing with very similar sorts of systems [

40,

41,

42,

90]. The geometries of the receptors and complexes were fully optimized with no restriction, which was assured as minima by the absence of imaginary vibrational frequencies. The binding energy of each anion with its receptor was calculated as the difference between the energy of the complex and the sum of the energies of separately optimized monomers. It was then corrected for basis set superposition error by the counterpoise [

91,

92] procedure. Gibbs free energies of each complexation reaction are computed at 298 K. To account for solvent effects, the polarizable conductor calculation model (CPCM) was applied [

93] with water as the solvent. This approach treats the surroundings as a polarizable continuum with dielectric constant of 78 but does not include explicit water molecules.

4. Discussion

Of the various tetrel atoms tested, Sn forms the strongest interactions with a chloride anion, which is followed closely by Pb. The tetrel bond is strongly enhanced when the TH3 group is perfluorinated to TF3. The interaction is further strengthened if the molecule containing the tetrel atom is endowed with a full positive charge. With this information as a starting point, the imidazolium group to which the SnF3 group is attached was varied in a methodical way to see if there were any ways to improve the binding. Binding is improved if this group is covalently attached to a Nitrogen atom of imidazolium rather than Carbon. On the other hand, replacement of imidazolium by triazolium had a slight weakening effect even though the tetrel bond is enhanced if the point of attachment is changed from C to N. The aromaticity of either of these two groups seems irrelevant since the replacement of imidazolium by its fully saturated five-membered ring analogue has no deleterious effect on the tetrel bond. Nor is the cyclic structure important, the binding is scarcely affected when a linear chain is used instead. The length of this chain on the N atom connection to SnF3 is unimportant as well since its shortening from n-butyl to a simple methyl group produces only a small enhancement. There seems little advantage in placing this amine group on a phenyl connector since doing so weakens the tetrel bond by perhaps 10%.

A chelating arrangement whereby the Cl

− forms tetrel bonds to two SnF

3 groups simultaneously increases the total binding energy but by far less than a factor of two. For example, placing two CH

3NH

2SnF

3+ groups on the phenyl ring produces only a magnification of the total binding energy by 21% when compared to that of a single such tetrel-bonding group. The size of this increase is not a result of geometric distortion since both θ(NSn·Cl) angles lie within 6° of linearity within this clathrate structure. Replacing the rigid phenyl ring by a more flexible (CH

2)

n alkane chain improves the overall binding regardless of the length of this chain. The optimal length appears to be

n = 2. Placing the two SnF

3 groups onto two separate molecules does not result in a stronger interaction, which suggests that steric constraints within the single dication molecule are not a detrimental factor. Just as adding a second group resulted in a magnification of only 1.2, a third such cation increases the binding free energy by the same factor. The modesty of the enhancement arising from a doubling of the positive charge on the receptor echoes recent [

99,

102] experimental findings.

It is worth reiterating that a very recent work [

79] suggested that Cl

− is an excellent choice as the test anion since its calculated binding to a series of Lewis acids mimics the experimental trends arising from NMR measurements. While the binding of Cl

− is just a bit stronger than the larger halides as well as NO

3−, HCO

3− binds more strongly to the MeNH

2SnF

3+ monocation. The smaller size of F

− with its concentrated negative charge leads to a larger binding free energy and OH

− even more so. The calculated trend of diminishing binding that accompanies the increasing size of the halide is consistent with experimental findings [

99]. These same trends are in evidence when these anions engage in a bifurcated tetrel bond with a uni-molecular SnF

3+NH

2(CH

2)

2NH

2SnF

3+ dication even though the magnitudes are larger. These differences in binding energy can result in highly selective receptors. For example, the 24 kcal/mol difference in ∆G binding of F

− over Cl

− in

Table 5 translates to a 10

17 equilibrium preference of the former over the latter. Even smaller differences in ∆G reflect substantial selectivity. The 3.4 kcal/mol advantage of Cl

− over Br

− yields a 300-fold equilibrium ratio. However, the very strong binding of OH

− might preclude the use of these receptors in basic environments where hydroxide would likely displace other anions.

In order to preferentially bind with an anion in solution, a receptor must successfully compete with counterions. The tetrel-bonding receptors examined here are extremely effective in this regard. Their binding energies with the various monoanions are much greater than those of K+ counterions despite the ability of the latter to move freely around each anion. The preference of any given anion for the monocationic tetrel-bonding receptors, over a K+ counterion, expressed as an equilibrium ratio, varies between 1027–1053. This preference is even larger for the dications when compared to a pair of K+ counterions, which rise up to as high as 1075.

It will be observed that both Gibbs free energy (∆G) and electronic energy (∆E) has been provided for all of the complexation reactions here. The former corrects the latter for zero-point vibrational energies as well as entropic effects. The latter additions make ∆G less negative than ∆E, but the discrepancy is fairly uniform and is typically on the order of 7–10 kcal/mol, which is a bit larger for the dications. As an end result, both energetic quantities obey similar trends.

It should be stressed that the self-consistent reaction field approach used here to model immersion in a solvent represents only an approximation of the full solvation effects. This model treats the solvent as a dielectric continuum that reacts to, and stabilizes, the charge distribution within the solute in an iterative manner. In doing so, it essentially averages over the many configurations that the solvent molecules will adopt over the course of a measurement. However, specific interactions of any individual solvent molecule with the solute are not explicitly evaluated. For this reason, the calculated energetics in water should be treated as only approximations. Nonetheless, this procedure has the virtue of providing some measure of the relative stabilization caused by immersing the solute in the solvent milieu. The trends in the data that emerge are likely realistic and differences from one system to the next of more than a few kcal/mol can be treated as meaningful. For example, the very large equilibrium ratios in

Table 7 between the preference of each anion for a tetrel-bonding receptor vs K

+ counterions are very unlikely to be reversed if other means of estimating solvation are employed.

Due to the high dielectric constant of water, solvation has quite a large impact on the binding energies. Taking the ImGeTH

3 complex with Cl

− as an example, the interaction energy in water of −1.9 kcal/mol rises to −14.6 kcal/mol in vacuo. The effect on the charged ImGeTF

3+ receptor is even more extreme since ∆E grows from −32.1 kcal/mol to −144.4 kcal/mol. Very similar increases are observed in ∆G. One may also consider how solvation contributes to the huge advantage that the tetrel-bonding receptors enjoy over K

+ in the competition for an anion.

Table 6 indicates a very weak interaction between K

+ and Cl

− in water with ∆G of only −1.72 kcal/mol, which is a major factor in the advantage of the tetrel-bonding receptor in the competition for this anion. The situation in the gas phase leads to much larger binding energies. Without the very substantial solvation energy of the cation, ∆G is greatly enlarged to −113.1 kcal/mol in vacuo. Taking the tetrel-bonding MeNH

2SnF

3+ cation as a counterpoint, its binding energy with Cl

− of −42.57 kcal/mol in water increases to −181.1 kcal/mol in vacuum, which is an even larger increment. As a result, the 41 kcal/mol advantage that MeNH

2SnF

3+ holds over K

+ in solution is increased to 68 kcal/mol without the moderating influence of water. Therefore, one may surmise that the stronger binding of tetrel-bonding species when compared to a small and compact counterion is intrinsic and is not an artifact of the solvation phenomena.

The reason for this reduced advantage in water derives from the solvation energies of the individual species. For exemplary purposes, one may consider the interactions of Cl− with both MeNH2SnF3+ and K+. Considering first the monomers, the solvation energy of K+ is larger by 9 kcal/mol than that of MeNH2SnF3+ due to its smaller size and more compact charge. A similar advantage accrues to the K+∙Cl− ion pair vs. the larger tetrel-bonded complex where it increases by 24 kcal/mol. This greater stabilization advantage of the K+∙Cl− complex vs the separate ions increases its binding energy relative to the MeNH2SnF3+ analogue. The net result is that the lesser binding energy of K+ vs the tetrel bond in the gas phase is reduced by 15 kcal/mol in water.

It might finally be remarked that some of these interactions between the receptor and the anion are quite strong since they are in excess of 50 kcal/mol. When combined with the rather short R(Sn·X) distances, it would be legitimate to refer to many of these interactions as bordering on covalent with the Sn atom adopting a hyper-valent bonding character. The arrangement of the atoms around the Sn atom in

Figure 2, for example, might best be described as pentavalent trigonal bipyramidal. An octahedral hexavalent environment, albeit a distorted one, could be invoked for a number of the bipodal receptors, which is shown in

Figure 4.

In conclusion, tetrel bonding offers a highly attractive way of forming strong complexes with anions that can easily extract these anions from an aqueous environment containing counter-ions. The -SnF3 group is particularly effective in this regard especially when the receptor contains a positive charge. A bipodal dicationic receptor has advantages over a mono-cation that can engage in only a single tetrel bond. It is hoped that the ideas presented here may guide researchers in the synthesis and testing of improved anion receptors.