Core RNAi Machinery and Sid1, a Component for Systemic RNAi, in the Hemipteran Insect, Aphis glycines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of Core RNAi Machinery and a Factor for Systemic RNAi

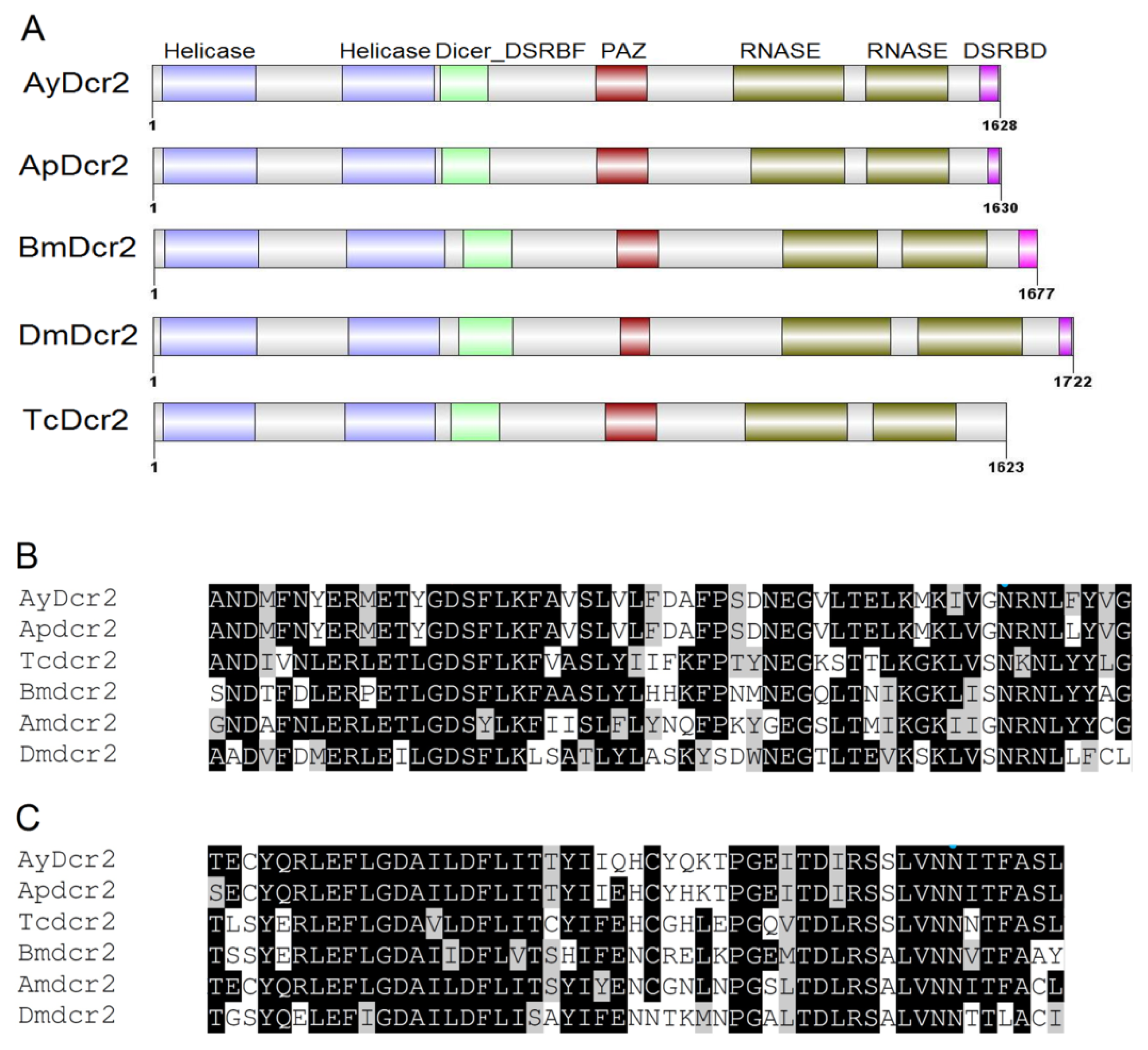

2.1.1. Characterization of AyDcr2

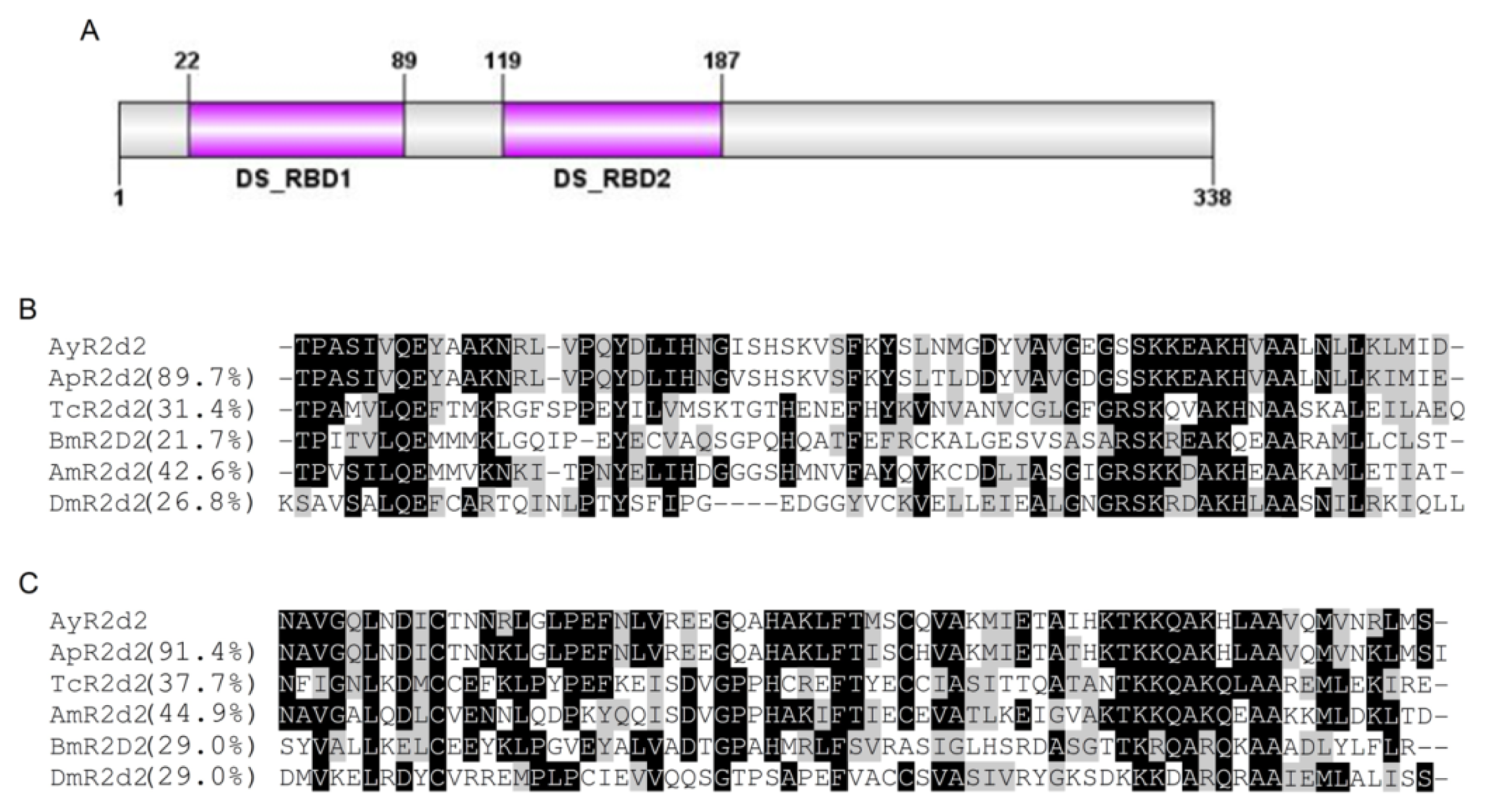

2.1.2. Characterization of AyR2d2

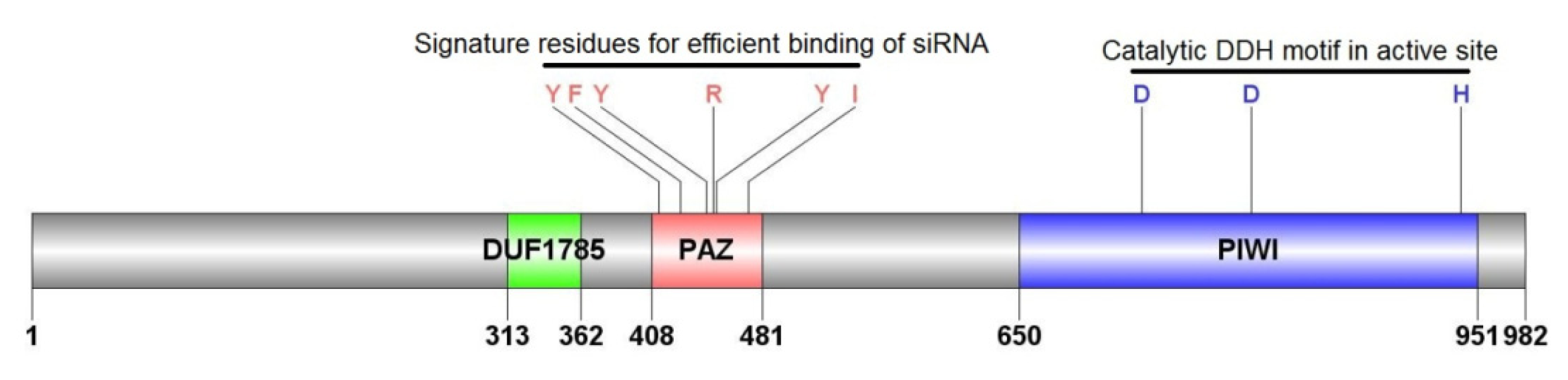

2.1.3. Characterization of AyAgo2

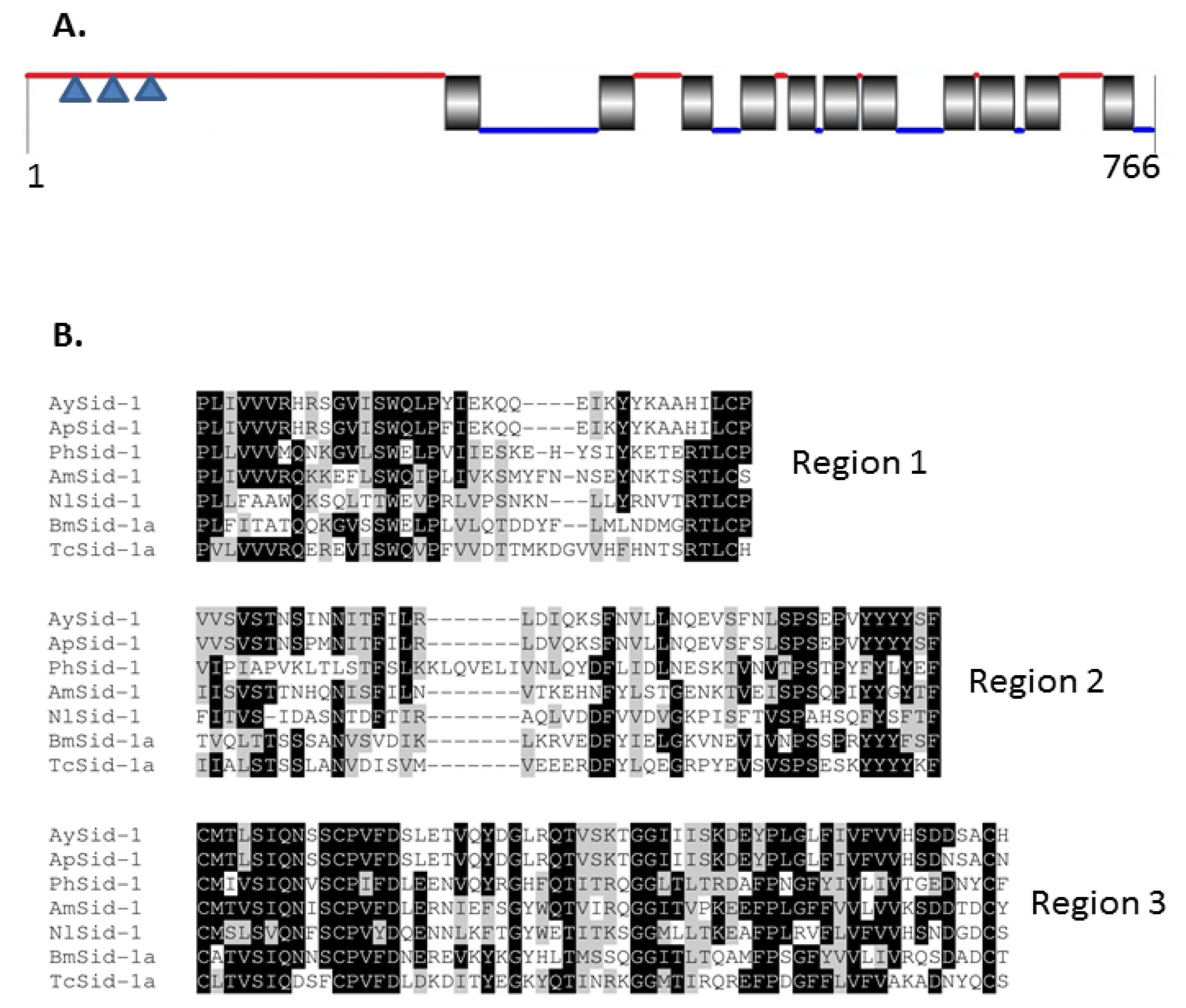

2.1.4. Characterization of AySid1

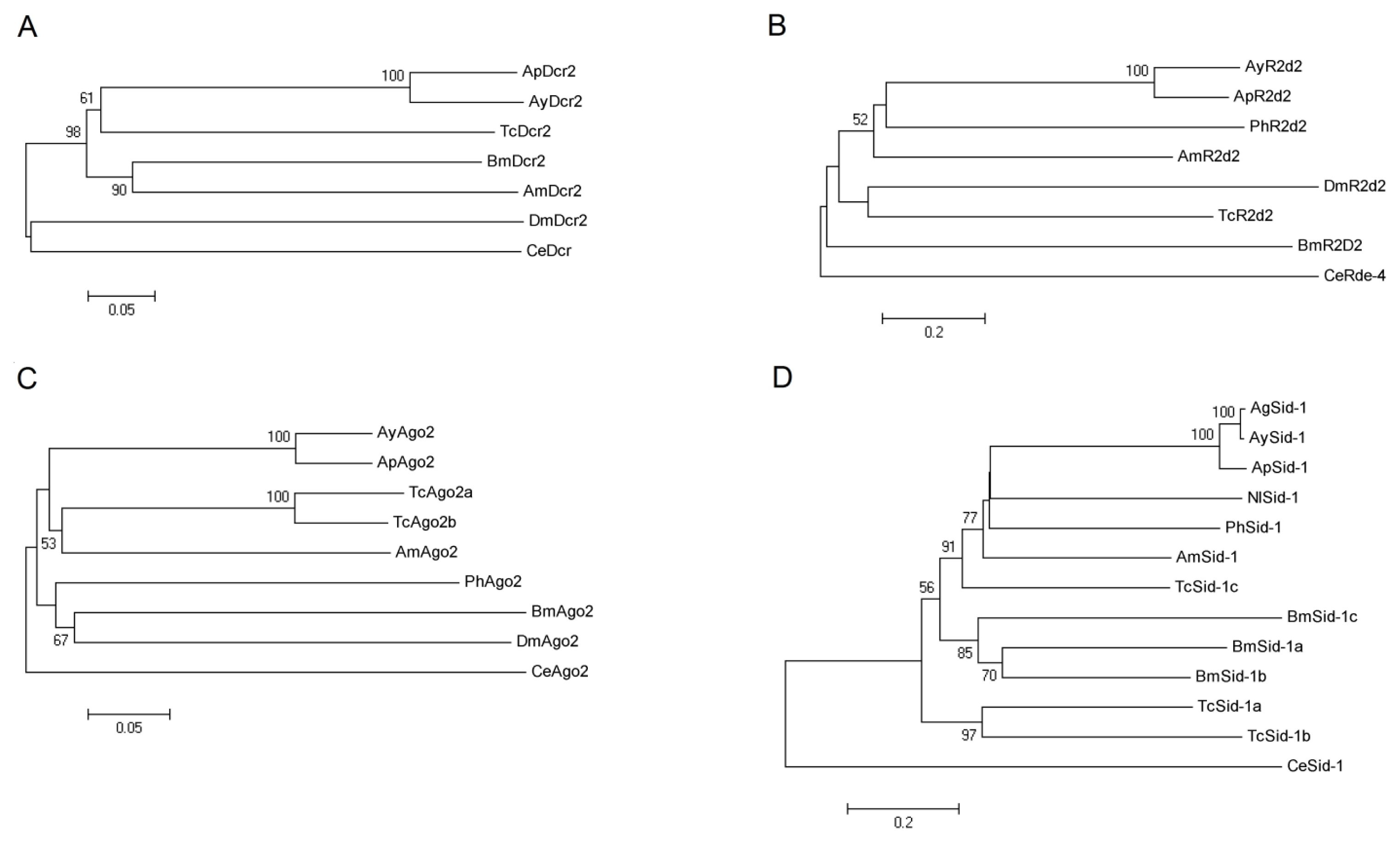

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of AyDcr2, AyR2d2, AyAgo2, and AySid1

2.2.1. Dcr2

2.2.2. R2d2

2.2.3. Ago2

2.2.4. Sid1

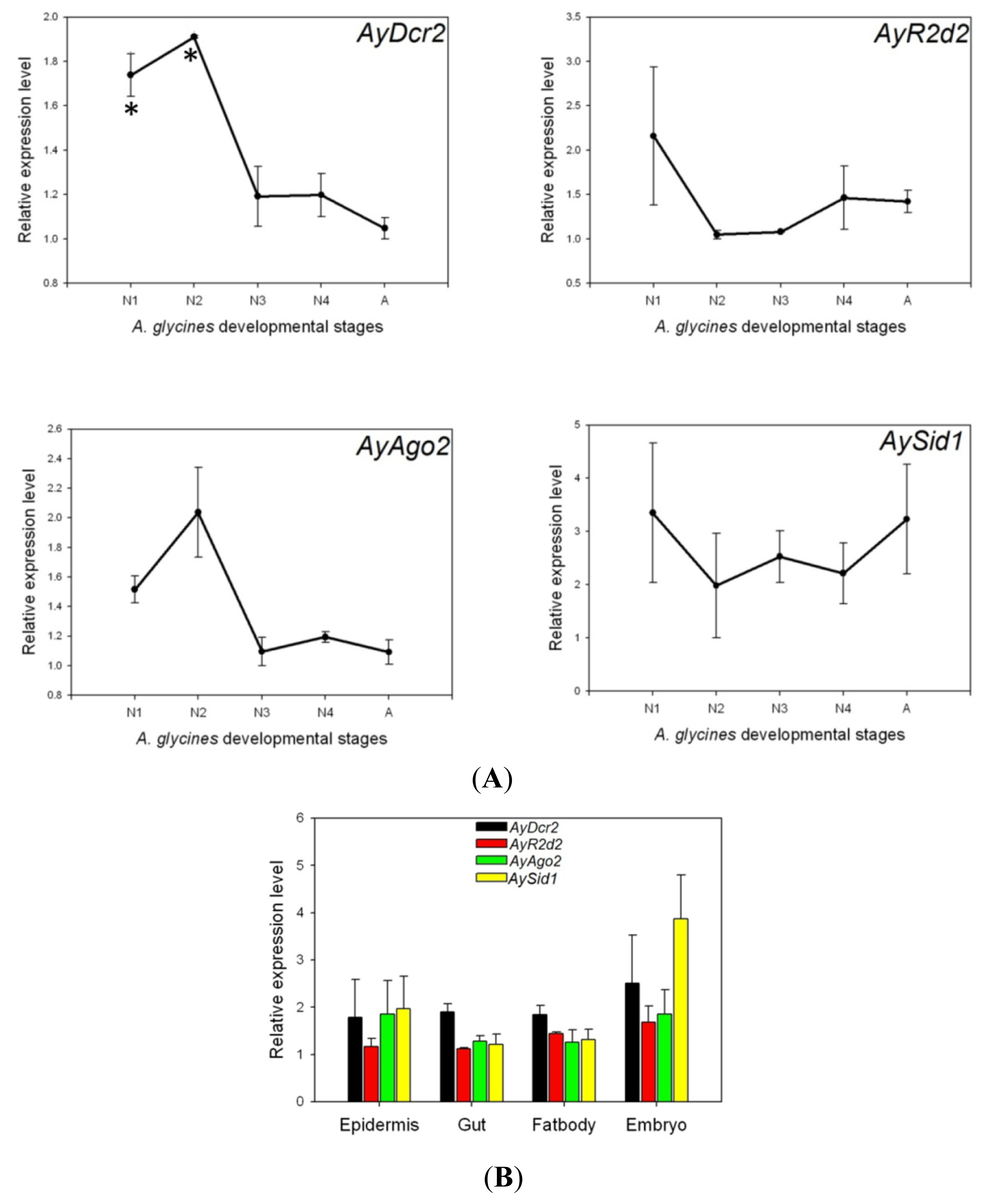

2.3. Expression Analysis of AyDcr2, AyR2d2, AyAgo2, and AySid1

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Identification and Analyses of Dcr2, R2d2, Ago2, and Sid1 cDNAs in A. glycines

4.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of insect Dcr2, R2d2, Ago2, and Sid1

4.3. Insect Culture

4.4. Tissue and Developmental Expression of Dcr2, R2d2, Ago2, and Sid1 in A. glycines

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Shelton, A.M.; Zhao, J.Z.; Roush, R.T. Economic, ecological, food safety, and social consequences of the deployment of Bt transgenic plants. Annu. Rev. Entomol 2002, 47, 845–881. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, T.; Cavato, T.; Brar, G.; Coombe, T.; DeGooyer, T.; Ford, S.; Groth, M.; Howe, A.; Johnson, S.; Kolacz, K.; et al. A method of controlling corn rootworm feeding using a Bacillus thuringiensis protein expressed in transgenic maize. Crop Sci 2005, 45, 931–938. [Google Scholar]

- Van Emden, H.F.; Harrington, R. Aphids as Crop Pests; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mellet, M.A.; Shoeman, A.S. Effect of Bt cotton on chrysopids, ladybird beetles and their prey aphids and whiteflies. Indian J. Exp. Biol 2007, 45, 554–562. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, C.A.; Wackers, F.L.; Pritchard, J.; Barrett, D.A.; Turlings, T.C. High susceptibility of bt maize to aphids enhances the performance of parasitoids of lepidopteran pests. PLoS One 2007, 2, e600. [Google Scholar]

- Cristofoletti, P.T.; Ribeiro, A.F.; Deraison, C.; Rahbe, Y.; Terra, W.R. Midgut adaptation and digestive enzyme distribution in a phloem feeding insect, the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Insect Physiol 2003, 49, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Head, G.; Brown, C.R.; Groth, M.E.; Duan, J.J. Cry1Ab protein levels in phytophagous insects feeding on transgenic corn. Implications for secondary exposure risk assessment. Ent. Exp. Appl 2001, 99, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Raps, A.; Kehr, J.; Gugerli, P.; Moar, W.J.; Bigler, F.; Hilbeck, A. Immunological analysis of phloem sap of Bacillus thurigiensis corn and of the nontarget herbivore Rhopalosiphum padi (Homoptera. Aphididae) for the presence of Cry1Ab. Mol. Ecol 2001, 10, 525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, A.; Klein, H.; Romeis, J.; Bigler, F. Uptake of Bt-toxin by herbivores feeding on transgenic maize and consequences for the predator Chrysoperla carnea. Ecol. Entomol 2002, 27, 441–447. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Chougule, N.P.; Bonning, B.C. Interaction of the Bacillus thuringiensis delta endotoxins Cry1Ac and Cry3Aa with the gut of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris). J. Invert. Path 2011, 107, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Schnepf, E.; Crickmore, N.; Van Rie, J.; Lereclus, D.; Baum, J.; Feitelson, J.; Zeigler, D.R.; Dean, D.H. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 1998, 62, 775–806. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, K.H.J.; Waterhouse, P.M. RNAi for insect-proof plants. Nat. Biotechnol 2007, 25, 1231–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, G.J. RNA interference. Nature 2002, 418, 244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Huvenne, H.; Smagghe, G. Mechanisms of dsRNA uptake in insects and potential of RNAi for pest control. A review. J. Insect. Physiol 2010, 56, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs. Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.W.; Voinnet, O. Antiviral immunity directed by small RNAs. Cell 2007, 130, 413–426. [Google Scholar]

- Mlotshwa, S.; Pruss, G.J.; Vance, V. Small RNAs in viral infection and host defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.H.; Aliyari, R.; Li, W.X.; Li, H.W.; Kim, K.; Carthew, R.; Atkinson, P.; Ding, S.-W. RNA interference directs innate immunity against viruses in adult Drosophila. Science 2006, 312, 452–454. [Google Scholar]

- Meister, G.; Tuschl, T. Mechanisms of gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature 2004, 431, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Jaubert-Possamai, S.; Rispe, C.; Tanguy, S.; Gordon, K.; Walsh, T.; Edwards, O.; Tagu, D. Expansion of the miRNA pathway in the hemipteran insect Acyrthosiphon pisum. Mol. Biol. Evol 2010, 27, 979–987. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, S.; Gibbs, R.A.; Weinstock, G.M.; Brown, S.J.; Denell, R.; Beeman, R.W.; Gibbs, R.; Beeman, R.W.; Brown, S.J.; Bucher, G.; et al. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature 2008, 452, 949–955. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, G.; Scholten, J.; Klingler, M. Parental RNAi in Tribolium (Coleoptera). Curr. Biol 2002, 12, R85–R86. [Google Scholar]

- Price, D.R.G.; Gatehouse, J.A. RNAi-mediated crop protection against insects. Trends Biotechnol 2008, 26, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Roignant, J.Y.; Carre, C.; Mugat, B.; Szymczak, D.; Lepesant, J.A.; Antoniewski, C. Absence of transitive and systemic pathways allows cell-specific and isoform-specific RNAi in Drosophila. RNA 2003, 9, 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, W.M.; Molodowitch, C.; Hunter, C.P. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science 2002, 295, 2456–2459. [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu, Y.; Miller, S.C.; Tomita, S.; Schoppmeier, M.; Grossmann, D.; Bucher, G. Exploring systemic RNA interference in insects. A genome-wide survey for RNAi genes in Tribolium. Genome Biol 2008, 9, R10. [Google Scholar]

- Aronstein, K.; Pankiw, T.; Saldivar, E. SID-1 is implicated in systemic gene silencing in the honey bee. J. Apic. Res 2006, 45, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, D.; Kang, L. The SID-1 double-stranded RNA transporter is not required for systemic RNAi in the migratory locust. RNA Biol 2012, 9, 663–671. [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale, D.W.; Heimpel, G.E.; Landis, D.A.; Brodeur, J.; Desneux, N. Ecology and management of the soybean aphid in North America. Annu. Rev. Entomol 2011, 56, 375–399. [Google Scholar]

- Tilmon, K.J.; Hodgson, E.W.; O’Neal, M.E.; Ragsdale, D.W. Biology of the soybean aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera. Aphididae) in the United States. J. Integr. Pest Manag 2011, 2, A1–A7. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.B.; Chirumamilla, A.; Hartman, G.L. Resistance and virulence in the soybean-Aphis glycines interaction. Euphytica 2012, 186, 635–646. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.S.; Hill, C.B.; Hartman, G.L.; Mian, M.A.R.; Diers, B.W. Discovery of soybean aphid biotypes. Crop Sci 2008, 48, 923–928. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, W.; Orantes, L.; Jun, T.-H.; Mittapalli, O.; Mian, M.A.R.; Michel, A.P. Combining next-generation sequencing strategies for rapid molecular resource development from an invasive aphid species, Aphis glycines. PLoS One 2010, 5, e11370. [Google Scholar]

- Preall, J.; He, Z.; Gorra, J.M.; Sontheimer, E.J. Short interfering RNA strand selection is independent of dsRNA processing polarity during RNAi in Drosophila. Curr. Biol 2006, 16, 530–535. [Google Scholar]

- Tomri, Y.; Matranga, C.; Haley, B.; Martinez, N.; Zamore, P.D. A protein sensor for siRNA asymmetry. Science 2004, 306, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Tomari, Y.; Zamore, P.D. Perspective: machines for RNAi. Gene Dev 2005, 19, 517–529. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Ye, K.; Patel, D.J. Structural basis for overhang-specific small interfering RNA recognition by the PAZ domain. Nature 2004, 429, 318–322. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, T.; Silverman, N. Bacterial recognition and signaling by the Drosophila IMD pathway. Cell. Microbiol 2005, 7, 461–469. [Google Scholar]

- Avadhanula, V.; Weasner, B.P.; Hardy, G.G.; Kumar, J.P.; Hardy, R.W. A novel system for the launch of alphavirus RNA synthesis reveals a role for the Imd pathway in arthropod antiviral response. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5, e1000582. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.; Jan, E.; Sarnow, P.; Schneider, D. The Imd pathway is involved in antiviral immune responses in Drosophila. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7436. [Google Scholar]

- Gerardo, N.M.; Altincicek, B.; Anselme, C.; Atamian, H.; Barribeau, S.M.; de Vos, M.; Duncan, E.J.; Evans, J.D.; Gabaldón, T.; Ghanim, M.; et al. Immunity and other defenses in pea aphids, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Genome Biol 2010, 11, R21. [Google Scholar]

- International Aphid Genomics Consortium. Genome sequence of the pea aphidAcyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS Biol 2010, 8, e1000313.

- Clark, A.J.; Perry, K.L. Transmissibility of field isolates of soybean viruses by Aphis glycines. Plant Dis 2002, 86, 1219–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Jaubert-Possamai, S.; Le Trionnaire, G.; Bonhomme, J.; Christophides, G.K.; Rispe, C.; Tagu, D. Gene knockdown by RNAi in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum. BMC Biotechnol 2007, 7, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Shakesby, A.J.; Wallace, I.S.; Isaacs, H.V.; Pritchard, J.; Roberts, D.M.; Douglas, A.E. A water-specific aquaporin involved in aphid osmoregulation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mutti, N.S.; Park, Y.; Reese, J.C.; Reeck, G.R. RNAi knockdown of a salivary transcript leading to lethality in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Insect Sci 2006, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pitino, M.; Coleman, A.D.; Maffei, M.E.; Ridout, C.J.; Hogenhout, S.A. Silencing of aphid genes by dsRNA feeding from plants. PLoS One 2011, 6, e25709. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, J.A.; Bogaert, T.; Clinton, W.; Heck, G.R.; Feldmann, P.; Ilagan, O.; Johnson, S.; Plaetinck, G.; Munyikwa, T.; Pleau, M.; et al. Control of coleopteran insect pests through RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol 2007, 25, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.-B.; Cai, W.-J.; Wang, J.-W.; Hong, G.-J.; Tao, X.Y.; Wang, L.-J.; Huang, Y.-P.; Chen, X.-Y. Silencing a cotton bollworm P450 monooxygenase gene by plant-mediated RNAi impairs larval tolerance of gossypol. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, L.; Knipple, D.C. Recent advances in RNA interference research in insects: Implications for future insect pest management strategies. Crop Prot 2013, 45, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Han, Z. Cloning and phylogenetic analysis of sid-1-like genes from aphids. J. Insect Sci 2008, 8, 30. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, E.; Sigrist, C.J.; Gattiker, A.; Bulliard, V.; Langendijk-Genevaux, P.S.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Hulo, N. ScanProsite: Detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, W362–W365. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, F.V.; Tolia, N.H.; Song, J.; Aragon, J.P.; Liu, J.; Hannon, G.J.; Leemor, J. Purified Argonaute2 and an siRNA form recombinant human RISC. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2005, 12, 340–349. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. ClustalW and ClustalX version 2. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar]

- Goujon, M.; McWilliam, H.; Li, W.; Valentin, F.; Squizzato, S.; Paern, J.; Lopez, R. A new bioinformatics analysis tools framework at EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, W695–W699. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Peterson, D.; Peterson, N.; Stecher, G.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol 2011, 28, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M.; Gojobori, T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol 1986, 3, 418–426. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.B.; Li, Y.; Hartman, G.L. Resistance of Glycine species and various cultivated legumes to the soybean aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae). J. Econ. Entomol 2004, 97, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, R.; Hulbert, S.; Schemerhorn, B.; Reese, J.C.; Whitworth, R.J.; Stuart, J.J.; Chen, M.S. Hessian fly-associated bacteria. Transmission, essentiality, and composition. PLoS One 2011, 6, e23170. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, R.; Mamidala, P.; Rouf, M.A.R.; Mittapalli, O.; Michel, A.P. Validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in soybean aphid, Aphis glycines Matsumura. J. Econ. Entomol 2012, 105, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, R.; Mian, M.R.; Mittapalli, O.; Michel, A.P. Characterization of a chitin synthase encoding gene and effect of diflubenzuron in soybean aphid, Aphis glycines. Int. J. Biol. Sci 2012, 8, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc 2008, 3, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar]

| Name | cDNA (bp) | Acc# a | ORF b | EPL (aa) c | MM (kDa) d | pIe | Match f | %ID g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AyDcr2 | 5877 | JX870425 | 487–5373 | 1628 | 187.96 | 6.23 | Ap(LOC100166428) | 85% |

| AyR2d2 | 1742 | JX870426 | 139–1155 | 338 | 37.88 | 5.84 | Ap(LOC100164758) | 73% |

| AyAgo2 | 3372 | JX870427 | 326–3274 | 982 | 111.46 | 9.63 | Ap(XP_003244047) | 78% |

| AySid1 | 2795 | JX870428 | 138–2438 | 766 | 88.39 | 7.02 | Ag(EF533711) | 99% |

Supplementary Files

© 2013 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Bansal, R.; Michel, A.P. Core RNAi Machinery and Sid1, a Component for Systemic RNAi, in the Hemipteran Insect, Aphis glycines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3786-3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14023786

Bansal R, Michel AP. Core RNAi Machinery and Sid1, a Component for Systemic RNAi, in the Hemipteran Insect, Aphis glycines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(2):3786-3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14023786

Chicago/Turabian StyleBansal, Raman, and Andy P. Michel. 2013. "Core RNAi Machinery and Sid1, a Component for Systemic RNAi, in the Hemipteran Insect, Aphis glycines" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 2: 3786-3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14023786