Abstract

We investigated the effect of auxin and acetylcholine on the expression of the tomato expansin gene LeEXPA2, a specific expansin gene expressed in elongating tomato hypocotyl segments. Since auxin interferes with clathrin-mediated endocytosis, in order to regulate cellular and developmental responses we produced protoplasts from tomato elongating hypocotyls and followed the endocytotic marker, FM4-64, internalization in response to treatments. Tomato protoplasts were observed during auxin and acetylcholine treatments after transient expression of chimerical markers of volume-control related compartments such as vacuoles. Here we describe the contribution of auxin and acetylcholine to LeEXPA2 expression regulation and we support the hypothesis that a possible subcellular target of acetylcholine signal is the vesicular transport, shedding some light on the characterization of this small molecule as local mediator in the plant physiological response.

Keywords:

cell elongation; acetylcholine; expansin; protoplasts; endocytosis; vesicle trafficking; vacuoles 1. Introduction

Cell elongation is a process known to be dependent on auxin. Although it has been studied for decades the mechanism is still not completely unravelled, since the response of the cell to the elongation stimulus is integrated and highly complex [1,2]. Recently, it has been proposed that auxin transport could involve secretion via an endocytic vesicle recycling process, at least at the root apex [3–8]. This vesicular secretion closely resembles the synaptic communication in animals [9–12] and, at the same time, supports the neurotransmitter-like concept of auxin [13]. Plants possess many homologous molecules that are similar to the neurotransmitters of the animal nervous system such as glutamate, GABA, serotonin, melatonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine [14–19]. The role of these molecules in plants is still far from understood [20–23]. These compounds can act as deterrents against predation, but they may somehow provide a signalling function also in plants. Supporting this role, receptors have been found [24,25]; among them the glutamate receptors are the better characterised (for review [26]). Serotonin and melatonin [21–23], as well as l-glutamate [27], appear to regulate the root system architecture. Acetylcholine (ACh) seems to mediate various physiological processes, such as phytochrome-based signalling [28–30], water balance [31], cell swelling [32,33], stomatal movement [34,35], root-shoot signal transduction [36] and cell elongation [37,38].

Expansins are well known key enzymes involved in cell elongation. They are encoded by a multigene family with unique and well-defined cell wall loosening effects, mediating cell wall relaxation in a pH-dependent manner [39] and enabling plant cells to elongate in response to their internal turgor pressure. LeEXPA2 belongs to the expansins multigene family, and it is up regulated by auxin in the young growing regions of tomato hypocotyl [40,41]. We previously investigated the role of auxin and sugars on LeEXPA2 mRNA expression in elongating tomato hypocotyl segments [42]. Sugar cross-talk with hormonal signalling is well documented [43–45]. Sugars are carbon and energy source in cell metabolism, but they are also a signal informing the plant about its metabolic state, affecting physiological processes such as germination, flowering and senescence [43,44,46–49].

In the present work we used LeEXPA2 expression to investigate the effect of auxin and ACh on cell elongation. Our research focuses on cell elongation with two main goals: to discriminate between the contribution of auxin and ACh on LeEXPA2 gene expression, and to identify the subcellular target of ACh signal in vesicular transport, contributing to the characterization of this kind of small molecule as local mediator in the plant physiological response.

2. Results

2.1. Determination of ACh Effect on Hypocotyl Segment Elongation

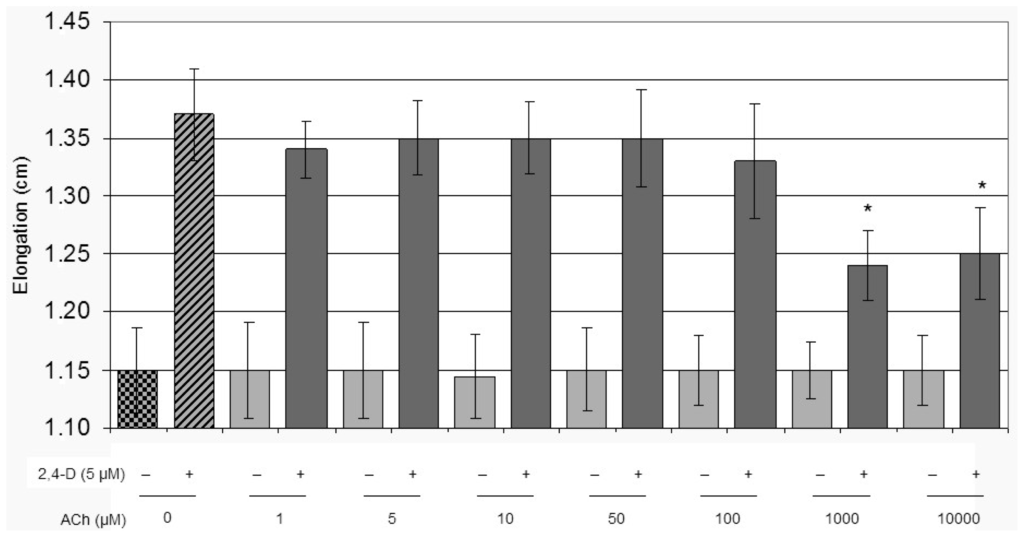

We investigated the effect of different concentrations of ACh alone or combined with a constant amount of the synthetic auxin 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) on hypocotyl segment elongation (Figure 1). The ACh dose definition was determined incubating tomato hypocotyl segments for 16 h. ACh concentrations higher than 100 μM spoiled the positive effect of 2,4-D, inhibiting segments elongation in presence of auxin. Considering that we do not know how ACh could be taken up from the medium by the plant tissue, a concentration of 50 μM ACh was chosen for further experiments. From our previous work [42] we already know that if the segment elongation has to be monitored, the presence of sucrose is an essential requirement to sustain the auxin-induced LeEXPA2 transcript in a 16 h-long experiment. We are also aware that sucrose is more than an energy supply in the auxin induced expansin transcription [41,42], and we decided to take these observations into account in all the experimental conditions.

Figure 1.

Effects of acetylcholine on tomato hypocotyl segments elongation. Hypocotyl segments were incubated for 16 h in buffer and increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (ACh) as indicated in the figure, with or without 5 μM 2,4-D. Hypocotyl segment length data are mean ± SE, n = 20. Group means were analysed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test (* p < 0.05).

2.2. ACh Alone Has a Moderate Induction Effect on LeEXPA2 Expression, but a Very Strong Effect When Combined with Auxin

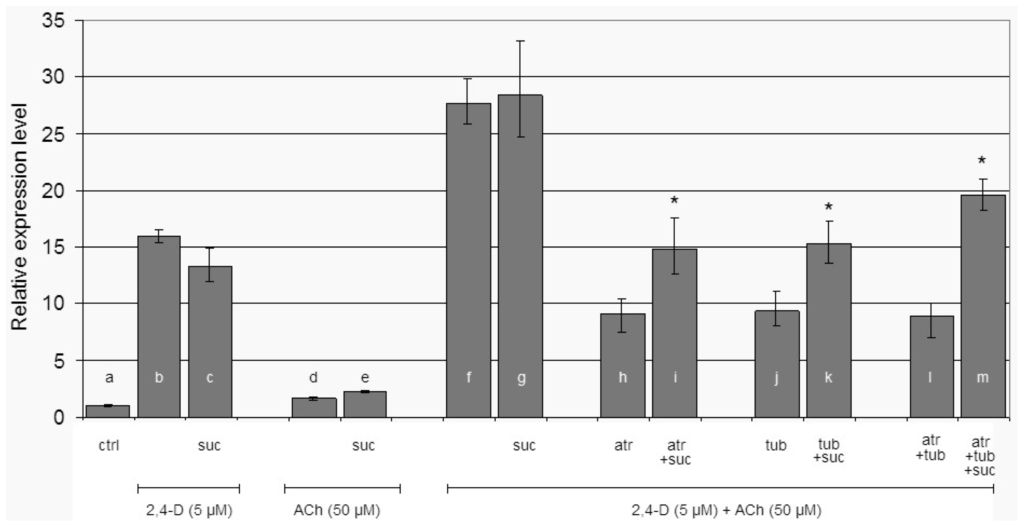

In order to avoid the effect of starvation we quantified LeEXPA2 transcript level in hypocotyl segments after 2 h of incubation. The possible signalling contribution of sucrose was taken into account quantifying LeEXPA2 in response to 2,4-D, ACh and their combination, with or without sucrose (Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference in LeEXPA2 mRNA accumulation between segments treated with 2,4-D or 2,4-D plus sucrose (Figure 2, histograms b,c). The supplying of ACh without or with sucrose does not affect LeEXPA2 transcription (Figure 2, histograms d,e), but when ACh was supplied together with 2,4-D, or with 2,4-D plus sucrose, the effect was more than simply additive (Figure 2, histograms f,g).

Figure 2.

Relative LeEXPA2 gene expression level. Relative LeEXPA2 gene expression in tomato hypocotyl segments after 2 h of incubation at different conditions as indicated in the figure. Ctrl = control in buffer alone; suc = sucrose (60 mM); atr = atropine (0.1 μM); tub = tubocurarine (0.1 μM). Pair of treatments (with or without sucrose) were analysed by ANOVA followed by Tukey test (* p < 0.05).

The specificity of ACh on gene induction was investigated by supplying two known antagonists of animal ACh receptors: atropine (atr) [50] and tubocurarine (tub) [51]. The observed effect was to decrease LeEXPA2 transcript to about 33% of the mRNA level registered in the relative control without antagonists (Figure 2, histograms h,j,l vs. f). LeEXPA2 mRNA was assessed to about 52% in presence of the single inhibitors when sucrose was added (Figure 2, histograms i,k vs. g), and to about 69% when the inhibitors were supplied together (Figure 2, histogram m vs. g). In all these last three different conditions (single inhibitors or the combination of both), sucrose statistically made the difference in maintaining expansin transcript.

2.3. Auxin and ACh Interfere with Endocytosis but Promote Early Steps of the Process

Hypocotyl elongation is certainly related to endomembrane traffic; synergistic effects of auxin and ACh may be explained by an effect on such traffic. We prepared protoplasts from etiolated hypocotyls isolated from seedlings grown in the same physiological conditions maintained in the other experiments and we loaded these cells with the endocytic tracer FM4-64. Protoplasts are cells deprived of their rigid cell wall that strongly influence plasma membrane turnover.

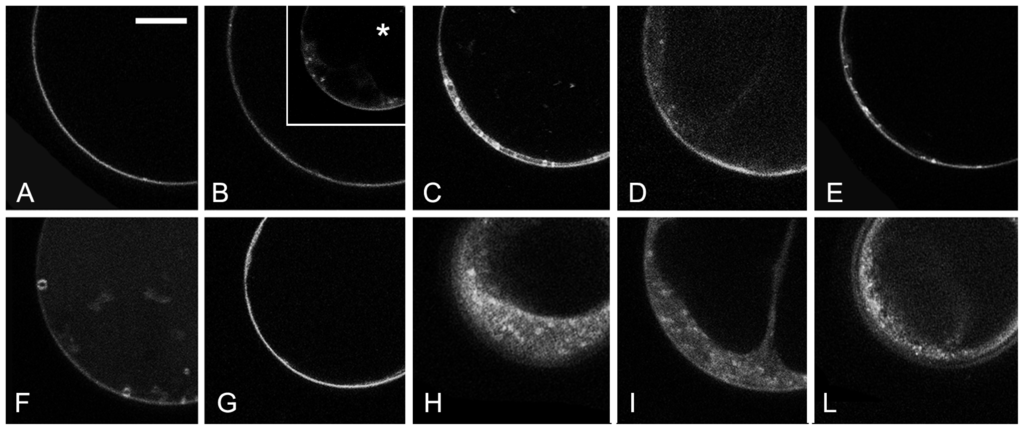

The prepared protoplasts had no visible plastids or rare etioplasts with a visible epifluorescent prolamellar body (not shown). Two sub-populations of cells, with large (above 30 μm) and small diameter (below 30 μm) could be distinguished. The few minutes time, required for the slide preparation, was sufficient to allow the loading of cell plasma membrane (PM) with FM4-64 and occasionally very small endocytic compartments were also visible within 10 min. Nonetheless, within the first 20 min, the labelling remained essentially limited to the PM in all large cells (Figure 3A). Small cells appeared to have a more active endocytosis with an earlier appearance of internal dotted structures (not shown). Brefeldin-A (BFA) treatment made more evident FM4-64 internalization in small cells, probably blocking the dye in newly forming BFA bodies (Figure 3B inset) but appeared to reduce the dye internalization in large cells (Figure 3B). It is known that BFA may have very specific effects in different cell types and also inhibit endocytosis [52,53]. We therefore decided to limit our observation to cells with a diameter above the 30 μm limit where endocytosis was inhibited and differences were more evident.

Figure 3.

FM4-64 internalization in tomato hypocotyl protoplasts. (A–E) Images of protoplasts within the first 20 min of staining. (A) In control conditions labelling remained essentially limited to the PM in all large cells; (B) Effect of BFA treatment appeared to reduce FM4-64 internalization in large cells even if in small cells BFA bodies rapidly appeared (inset *); (C) Effect of treatment of protoplasts with 5 μM Auxin; (D) Effect of treatment with 50 μM ACh; and (E) Effect of combined chemicals; (F–L) Images of protoplast after 80 min of staining. (F) Control protoplast with defined late endosomes; (G) BFA treated cell with no internalization of the dye; (H) Protoplast treated with Auxin; (I) Protoplast treated with ACh; and (L) Protoplast treated with combined chemicals. Scale bar: 10 μm.

The chemical protoplasts treatment with 5 μM 2,4-D (Figure 3C), 50 μM ACh (Figure 3D) or the combination of both (Figure 3E) induced an increase of very small dotted structures visible immediately after FM4-64 loading. After 80 min of FM4-64 internalization, control protoplasts presented well defined late endosomes with a diameter over 1 μm (Figure 3F), while BFA treated cells showed almost no internalization of the dye (Figure 3G). The treatment with the synthetic auxin (Figure 3H), ACh (Figure 3I) or the two combined chemicals (Figure 3L) inhibited the correct endocytosis inducing an aberrant FM4-64 distribution pattern that appeared almost diffused in the cytosol.

2.4. Auxin and ACh Affect the Compartment Involved in Golgi-Independent ER-to-Vacuole Transport

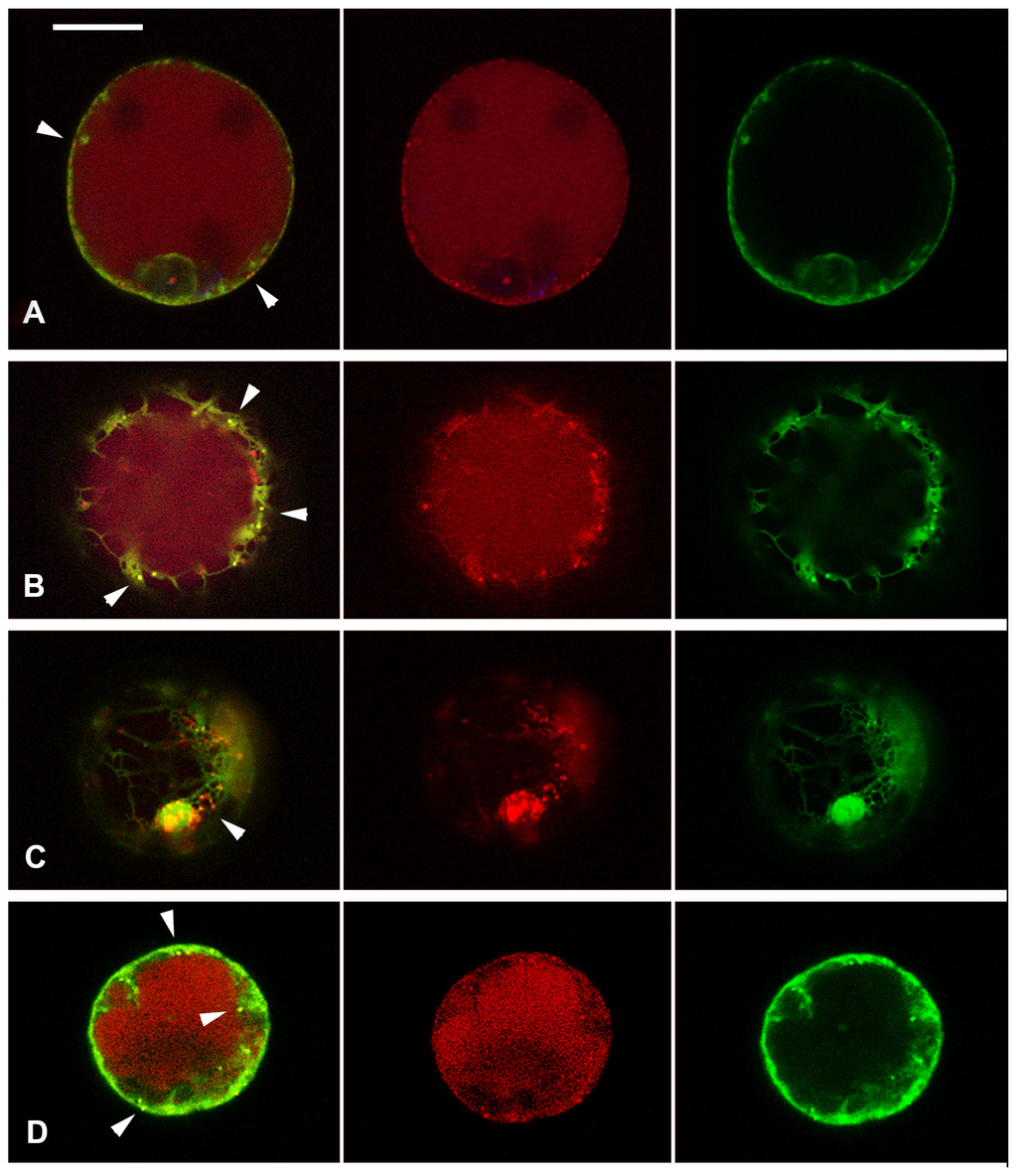

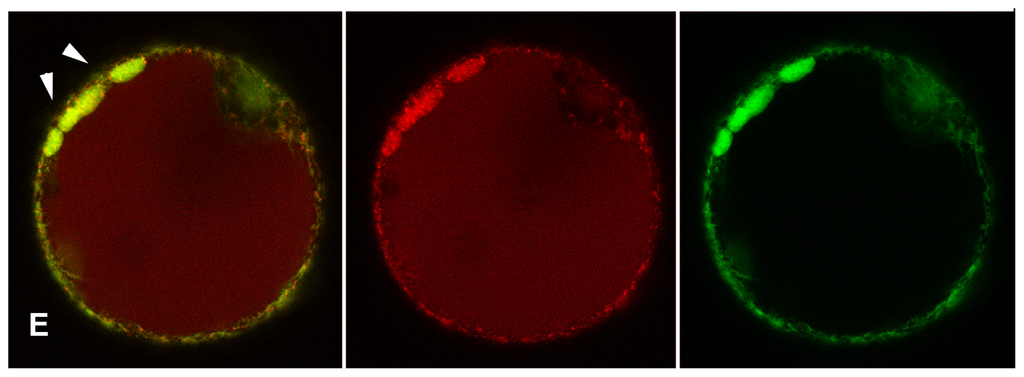

The central vacuole is essential to drive plant cell expansion [54]. For this reason, the two well-documented vacuolar fluorescent reporters AleuRFP and GFPChi [55] were expressed in tomato hypocotyl protoplasts to visualize vacuoles and to monitor auxin and ACh effects on endocytic compartments organization. GFPChi is the result of the fusion of GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) with the C-terminal VSD of tobacco chitinase, while AleuRFP comes from the N-terminal fusion of the Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP) with the sequence-specific VSD of the barley cysteine protease aleurain. It has been reported that AleuRFP transits through a prevacuolar compartment (PVC), which is identified as late endosome (LE), while GFPChi reaches the vacuole bypassing Golgi stacks [56]. In Arabidopsis [55] and Tobacco [56] protoplasts, GFPChi and AleuRFP partially colocalize in the central vacuole (Lytic Vacuole = LV). In tomato hypocotyl protoplasts AleuRFP was distributed as expected in PVC and LV while GFPChi was very rarely observed in the LV and its localization was generally restricted to the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Tomato hypocotyl protoplasts transiently co-transformed with GFPChi (in green colour) and AleuRFP (in red colour). (A) Cell in control conditions, GFPChi is restricted to the ER and only AleuRFP labels small punctate structures (white arrows); (B) Cell treated with Auxin, it induces concentration of GFPChi in small punctate structures that colocalized partially with those labeled by AleuRFP (white arrows); (C) Cell treated with ACh, it caused accumulation of GFPChi in small vacuoles surrounded by several AleuRFP labeled structures (white arrow); (D) Cell treated with the two chemical combined, the treatment appeared very stressful but again it was evident that GFPChi and AleuRFP colocalized in punctate structures (white arrows); and (E) Cell treated with BFA induced bodies where GFPChi and AleuRFP colocalized partially (white arrows) but colocalization was not observed in the small discrete compartments exclusively labeled by AleuRFP. Scale bar: 20 μm.

All chemical treatments visibly stressed the cells. When 2,4-D was applied, GFPChi distribution was altered and the reporter was concentrated in small punctate structures that colocalized partially with AleuRFP positive PVC (Figure 4B). ACh caused accumulation of GFPChi in small compartments, large enough to be named vacuoles, surrounded by many PVC that appeared to be associated (Figure 4C). The two chemicals combined were very stressful for the cells, but it was evident that again GFPChi and AleuRFP colocalized in PVCs (Figure 4D). BFA treatments induced BFA-bodies where GFPChi and AleuRFP partially colocalized similarly to that observed in tobacco [56]. Colocalization was not observed in the small discrete compartments that may be identified as PVCs (Figure 4E) where, on the contrary, the two fluorescent markers colocalized during auxin and ACh treatments (Figure 4B–D).

3. Discussion

Expansins were first identified by McQueen-Mason and colleagues [57] and are members of a multigene family known to be cell-wall-loosening enzymes. They allow turgor-driven cell expansion by disrupting hydrogen bonds of the wall polysaccharides, and they are involved in a variety of physiological responses such as root growth [58], internode elongation [59], leaf development [60], fruit development [61], floral development [62], fruit maturation [63,64], and seed germination [65]. They are expressed in the apical meristem [66] and in active elongating tomato hypocotyl tissues [41,42,67]; they also play important roles during abiotic stress response [68–70]. Expansin activity is shown to be regulated by many factors. The promotor region includes target sites for transcription factors regulated by hormones such as auxin [67,71], gibberellins [72,73], cytokinin [74,75], ethylene [76,77], or by light [41].

In the experimental system based on tomato elongating hypocotyl segments used here, LeEXPA2 is induced by auxin and it is directly involved in cell elongation confirming what was previously reported [40–42,67]. After 2 h of treatment, there is no statistically significant difference in LeEXPA2 transcript amount between hypocotyl segments subject to 2,4-D, or 2,4-D plus sugar (Figure 2). This observation may indicate that sugar has no signalling role on its own, or–at least–that it is fully masked by auxin effect. When ACh is added to the medium, the presence of sucrose seems to cause a slight increase in LeEXPA2 mRNA amount. Sucrose has proven to possess a signalling role in many cases [78–81], but for a molecule so tightly integrated in the plant cell metabolism it is difficult to separate its contribution as metabolic/energetic compound from the signalling one. Considering LeEXPA2 transcript level accumulation upon ACh or auxin stimulation (Figure 2), while ACh alone does not seem to induce any changes in LeEXPA2 transcript level, the combination of both auxin and ACh causes a strong increase in expansin transcript abundance, more than additive when compared to the effect due to the single chemicals.

ACh has already been shown to possess some of the effects historically ascribed to auxin, such as rooting of leaf explants [82], promoting lateral roots [83], interacting with phytochrome [28], and mediating coleoptyl segment elongation [37,38]. In our experimental system, no additive effect was observed in segment elongation when auxin and Ach—with or without sucrose—were added to the medium (data not shown); maximum elongation after 16 h was observed in hypocotyl segments treated with auxin alone. Our observation differs from Lawson and colleagues [38], who reported that higher concentration of ACh had an inhibitory effect on elongation. In any case, the literature does not provide support in the definition of an optimal physiological concentration of ACh in plants. A wide range of ACh concentration is described, from 10 μM in oat coleoptile segments [37], to 10−4–10−2 M in pea chloroplasts [84], 10−8–10−2 M in wheat protoplasts [85], 23 pmol/g in Arabidopsis [86], and 2.94 μmol/g in Bamboo shoot [86,87]. An even wider range of ACh concentration was used in various experimental systems: 0.3 mM on germinating beans [29], 0.1 mM on oat coleoptile segments [37], 10 μM on peels from Vicia faba leaves [35], and 1 nM on germinating radish [83]. We failed to measure the endogenous concentration of ACh in tomato hypocotyls; therefore we monitored the effect of ACh on hypocotyl segments elongation in order to identify an optimal concentration for the experiments (Figure 1). An ACh concentration beyond 50 mM appeared to negatively interfere with the auxin driven elongation process, supporting the observations of Lawson and colleagues (1978) [38]; we therefore adopted the concentration just below (50 mM). Further experiments are needed to understand whether smaller concentrations may be sufficient to induce expansin transcription.

The ACh effect described here is specific. The elongation induced by the combined action of ACh and auxin, either in presence or in absence of sucrose, was prevented by adding to the medium the inhibitors of mammal ACh receptors (Figure 2). The evidence of a cholinergic system in plants is still lacking [14], but ACh and the enzymes necessary to its biosynthesis and degradation are already been found in life forms without a mammal-like nervous system, such as bacteria, fungi, yeast, and finally plants [31,86]. The application of specific agonists such as muscarin and nicotine, and antagonists such as atropine and tubocurarine [50,51] indirectly suggests the possible existence of the two main receptors types (muscarinic and nicotinic). Since plants possess all the neurotransmitter-like molecules proper of the mammalian nervous system, such as dopamine, melatonin, serotonin, GABA, and glutamate [14,15,17,18,88,89], it is reasonable to hypothesize that these compounds could be involved in some kind of signal transmission [18,90,91] in addition to a possible metabolic role. In some cases these molecules act as deterrents for plant predation, but for some of them the presence of plant-specific receptors has been proven [24–26,92]. Atropine and tubocurarine efficacy in our experimental system might support the indirect evidence of the existence of an ACh receptor: a receptor that may be competitively bound by selective antagonistic compounds.

We also investigated the modification of the cell upon auxin and ACh stimulation, observing the alteration of membrane and vesicular traffic. It has already been proven that cell-to-cell auxin transport depends on a vesicular traffic, and that auxin loading involves carriers derived from plasma membrane and endosome recycling [18,19,93]. In human and animal systems, ACh is also packaged into vesicles after been synthesized. ACh vesicular import occurs by means of a carrier protein on the vesicle membrane. Once packaged, ACh is stored into the synaptic vesicles pool [94–96]. Synergistic effects of auxin and ACh may be explained by an effect on membrane traffic; we used protoplasts from etiolated hypocotyls to test this hypothesis. Protoplasts are expected to provide a reasonable indication of plasma membrane turnover and endomembrane organization in the differentiated cells of the studied tissue [97–99].

Protoplasts from etiolated hypocotyls, similarly to other protoplasts populations [55,100], had no less than two distinct sub-populations: one with large diameter (above 30 μm), the other with small diameter (below 30 μm). Being aware that vesicle traffic and endomembrane organization may be different, and that BFA (chosen as control treatment) may have very specific effect in different cell types [53], we decided to limit our observations to cells with a diameter above the 30 μm. Protoplasts were stained with the styryl dye FM4-64, commonly used as endocytic tracer [101–103] and a BFA treatment was used as a control of the cell behaviour. We found that the drug had different effects on the two size-based subpopulations of the cells derived from tomato hypocotyl. While BFA induced rapid accumulation of the dye in small cells, it inhibited FM4-64 internalization in large cells. Several authors stressed that BFA action is determined by the localization and concentration of resistant and sensitive ARF (ADP-ribosylation factor)/ARF-GEF (Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factor) complexes and can have different effects in different tissues [52]. On the contrary, the treatments of cells with 2,4-D 5 μM, ACh 50 μM or the two combined chemicals, induced also in large cells a rapid increase of very small dotted structures immediately visible after FM4-64 loading. Staining of the PM drastically decreased indicating a clear acceleration of the dye internalization. The observed increased internalization was anyhow different from the normal endocytotic process. In fact, after longer internalization time, when well-defined late endosomes should have been visible, the correct endocytosis progress appeared to be impaired. 80 min after FM4-64 loading, the marker did not progress in the internal membranes, especially the late endosome; on the contrary it was trapped in very small vesicles dispersed in the cytosol. The normal progression of the endocytotic pathway was altered. Both auxin and ACh did not prevent FM4-64 internalization but affected a second step of endocytosis leading to large late endosomes. BFA treated cells provided a control situation in which almost no internalization of the dye was observed. In this case the dye remained confined to the PM. This control was useful to clearly distinguish auxin and ACh effect from a simple endocytosis inhibition. The existence of several endocytotic and recycling pathways was proven by the production of functional BFA-sensitive or BFA-resistant ARF-GEFs variants [104]. It was shown that BFA-sensitive GNOM regulated PIN1 and PIN3 recycling [104,105], but it was not involved in the recycling of AUXIN-RESISTANT1 (AUX1), PIN2, and PM-located H+-ATPase [106] to the PM. The possibility of differential effects suggests the existence of multiple functionally distinct early/recycling endosomes (REs). GNOM partially co-localizes with FM4-64 and REs might then be part of the Trans Golgi Network (TGN) as suggested by [104], nonetheless the two compartments have a different sensitivity to BFA [106].

Certainly the auxin and ACh effect is different from the effect of BFA. BFA disrupts Golgi-based secretion and leads to the formation of endomembrane bodies (BFA bodies) that incorporate early endosomes and TGN components as well as Golgi resident proteins. BFA also aggregates the endosomal population of BRI1 [107,108] and disrupts the endocytosis of PIN2, AUX1, PIN1 and PIN7 [105,106,108]. We speculate that the very small FM4-64-labelled dots visualized during auxin and ACh treatments are compartments characterized by the transit of PIN1 and PIN7 [106,107].

Looking for further information on the effect of auxin and ACh treatments on late endosomal compartments, we investigated post-Golgi compartments, labelling them with two known vacuolar markers: GFPChi and AleuRFP [55]. These reporter proteins follow two different and independent routes to the vacuole [55,56,100]. BFA also had a differential effect on the two markers. The inhibition of COPII trafficking by a specific dominant-negative mutant (NtSar1h74l) confirmed that GFPChi transport from the ER to the vacuole is not fully dependent on the Golgi apparatus [56]; suggesting the existence of a not yet characterized intermediate compartment. On the contrary, AleuRFP/GFP transits through Golgi stacks. In Arabidopsis [55] and Tobacco [56] protoplasts, GFPChi and AleuRFP partially colocalize in the central vacuole (Lytic Vacuole = LV) but never colocalize in the intermediate compartments [56]. In tomato protoplasts from etiolated hypocotyls GFPChi was never observed in the LV. In the absence of a biochemical evaluation, this is not the definitive indication that this marker does not reach the LV because proteases and low pH may reduce GFPChi fluorescence in the vacuole below detection limits [109]. Our attention was in any case focused on intermediate compartments more than on LV.

We observed that GFPChi was distributed essentially in the ER. The distribution was altered through auxin and ACh, both inducing the formation of small compartments labelled by GFPChi. AleuRFP pattern suffered no alteration. The small compartments labelled by GFPChi under auxin treatment were not an altered ER domain but colocalized with the PVC labelled by AleuRFP (Figure 4B). Also ACh induced the formation of discrete compartments. In this case small and large compartments were labelled. The small ones colocalized with AleuRFP-positive PVC (Figure 4C). The larger compartments may be defined small vacuoles by their size, larger than 1 μm. BFA treatment induced the formation of BFA bodies not very different from the “small vacuoles” induced by ACh, but colocalization of the two markers was never observed in the PVC.

We can speculate that both auxin and ACh, inhibiting a secondary step of endocytosis, prevent the formation of the intermediate compartment responsible for the correct sorting of GFPChi or, in the case of tomato cells, for its recovery to the ER. As a consequence, auxin and ACh cause the merging of GFPChi and AleuRFP sorting pathways and the colocalization of the two markers in the PVC. This effect may result in an indirect stimulation of the LV expansion and of cell expansion.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Experiments were performed with 5-day-old tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicon cv. St. Pierre). Seeds of tomato were sown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium with 2 g/L Gelrite Gellan Gum (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) in covered plastic sterile vessels (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, The Netherlands), and then plants were grown in the dark for 5 days at 24 °C.

4.2. Hypocotyl Segment Treatment

Seedlings from 2.8 to 3.2 cm long were cut exactly below the apical hook in order to obtain one cm long segment. Measurement and cutting were conducted under a green safelight. Segments were incubated in Petri dishes containing 2.5 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 24 °C in the dark with gentle shaking as pre-treatment rinse in order to deplete endogenous auxin and other interfering putative signaling molecules [42,67]. After 2 h, the rinsing buffer was discarded and the segments were transferred into a new fresh buffer containing or not (control) different treatments (2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid), sucrose, acetylcholine, atropine, tubocurarine) in different combinations. Sucrose and 2,4-D were purchased from Duchefa. Acetylcholine, atropine and tubocurarine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

4.3. RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

Total RNA isolation was performed using RNAqueous kit (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Monza, Italy), and then total RNA was DNase-treated using Turbo DNA-Free kit (Ambion) to remove possible DNA contamination. The quantity and quality of RNA samples were measured on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND 1000, NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) at 260/280 nm. Reverse transcription was performed using ImProm-II Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Milan, Italy) and the cDNA concentration of each sample was normalised to 50 ng/μL prior to the qRT-PCR reactions.

4.4. Quantitative PCR

Quantitative-PCR (q-PCR) analysis was carried out using a TaqMan probe. The sequence used for the design of the probe for LeEXPA2 gene was identified sequencing the fragment obtained using the primers described by Caderas et al. (2000) [41]. The probe consists of 248 bases with the target site for the probe located at position 186 of the sequence, while 18S rRNA was used as reference housekeeping gene because of its high stability [110] and lack of variation in the experimental treatments. Quantitative PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM(R) 7300 SequenceDetection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in MicroAmp Optical 96-Well Reaction Plates. TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used, containing AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase. Data were evaluated in triplicate and the gene expression was calculated using the formula 2−(ΔΔCt).

4.5. FM4-64 Dye Staining and Transient Transformation of Hypocotyl Protoplasts

Protoplasts were obtained from hypocotyl segments grown as for the elongation assay. The manipulation, performed under normal white light, was performed as previously described for other plant material [55].

The FM4-64 staining was performed after 4 h of standard incubation at 26 °C. No transformation was performed in these cases. 100 μM FM4-64 (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) was used from a stock (1 mM) in 0.4 M mannitol. After 1 min the cells were washed with W5 (NaCl 154 mM; CaCls 125 mM; KCl 5 mM; Glucose 5 mM) and observed within 80 min. Images were produced as specified in the result description. The constructs GFPChi and AleuRFP, used for transient transformation, were built previously [100,102]. Protoplasts were examined with a confocal laser-microscope (LSM 710 Zeiss, ZEN software, GmbH, Jena, Germany). To detect FM4-64 fluorescence, the He-Ne laser was used to produce a 543-nm excitation and the emission was recorded with the 560–615 nm filter set. GFPChi was detected in the lambda range 505–530 nm, assigning the green colour, AleuRFP within 560–615 nm, assigning the red colour. Excitation wavelengths of 488 and 543 nm were used. The laser power was set to a minimum and appropriate controls were made to ensure there was no bleed-through from one channel to the other. Images were mounted using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software (Mountain View, CA, USA).

5. Conclusions

Auxin and ACh effects on endomembranes seem to converge on the same traffic events but appear to be in any case distinct. The synergistic effect of auxin and ACh on LeEXPA2 transcription and on hypocotyl elongation, associated with the observed diversified effect on endomembranes, supports the interpretation of two distinct signalling molecules capable of synergistic effects on elongation. A more accurate dissection of the molecular processes, supported by the increasing bibliography on auxin and brassinosteroids, has to be performed to fully explain the action of ACh in plants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the contribution of the Interdepartmental Centre Biogest-Siteia of the High Technology Network of the Emilia Romagna Region, and the Italian project “Reti di Laboratori Pubblici di Ricerca per la Selezione, Caratterizzazione e Conservazione di Germoplasma 2009”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Author ContributionsThis work is the result of the collaboration between L.A. and G.P.D.S. L.A. defined the research theme. L.A. designed methods and experiments for the molecular part, G.P.D.S. for the citological one. S.F., F.B. and G.P.D.S. performed the experiments. L.A., G.P. and G.P.D.S. analysed and discussed the data, interpreted the results and wrote the paper.

References

- Geitmann, A.; Ortega, J.K.E. Mechanics and modeling of plant cell growth. Trends Plant Sci 2009, 14, 467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, R.E. Auxin and cell elongation. In Plant Hormones: Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! Revised 3rd ed.; Davies, P.J., Ed.; Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg: London, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 204–220. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Šamaj, J.; Menzel, D. Polar transport of auxin: Carrier-mediated flux across the plasma membrane or neurotransmitter-like secretion? Trends Cell Biol 2003, 13, 282–285. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Xue, H.W. Arabidopsis PLDζ2 regulates vesicle trafficking and is required for auxin response. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso, S.; Marras, A.M.; Mugnai, S.; Schlicht, M.; Zarsky, V.; Li, G.; Song, L.; Xue, H.-W.; Baluška, F. Phospholipase Dζ 2 drives vesicular secretion of auxin for its polar cell-cell transport in the transition zone of the root apex. Plant Signal. Behav 2007, 2, 240–244. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H.; Hou, N.Y.; Schlicht, M.; Wan, Y.; Mancuso, S.; Baluška, F. Aluminium toxicity targets PIN2 in Arabidopsis root apices: Effects on PIN2 endocytosis vesicular recycling and polar auxin transport. Chin. Sci. Bull 2008, 53, 2480–2487. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Song, L.; Xue, H.W. Membrane steroid binding protein 1 (MSBP1) stimulates tropism by regulating vesicle trafficking and auxin redistribution. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Mancuso, S. Microorganism and filamentous fungi drive evolution of plant synapses. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 2013, 3, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Šamaj, J.; Wojtaszek, P.; Volkmann, D.; Menzel, D. Cytoskeleton—plasma membrane—cell wall continuum in plants: Emerging links revisited. Plant Physiol 2003, 133, 482–491. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Wojtaszek, P.; Volkmann, D.; Barlow, P.W. The architecture of polarized cell growth: the unique status of elongating plant cells. Bioessays 2003, 25, 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Volkmann, D.; Menzel, D. Plant synapses: Actin-based domains for cell-to-cell communication. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 3, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Mancuso, S.; Volkmann, D.; Barlow, P.W. The “root-brain” hypothesis of Charles and Francis Darwin: Revival after more than 125 years. Plant Signal. Behav 2009, 4, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F. Actin Myosin VIII and ABP1 as central organizers of auxin-secreting synapses. In Plant Electrophysiology; Volkov, A.G., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Tretyn, A.; Kendrick, R.E. Acetylcholine in plants: Presence metabolism and mechanism of action. Bot. Rev 1991, 57, 33–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kuklin, A.I.; Conger, B.V. Catecholamines in plants. J. Plant Growth Regul 1995, 14, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Odjakova, M.; Hadjiivanova, C. Animal neurotransmitter substances in plants. Bulg. J. Plant Physiol 1997, 23, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Roshchina, V. Neurotransmitters in Plant Life; Science Publishers Inc.: New Hempshire, NE, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Mancuso, S.; Volkmann, D.; Barlow, P. Root apices as plant command centres: The unique “brain-like” status of the root apex transition zone. Biologia 2004, 59, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, E.D.; Stahlberg, R.; Mancuso, S.; Vivanco, J.; Baluška, F.; van Volkenburgh, E. Plant neurobiology: An integrated view of plant signaling. Trends Plant Sci 2006, 11, 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna, A.; Giridhar, P.; Ravishankar, G.A. Phytoserotonin: A review. Plant Signal. Behav 2011, 6, 800–809. [Google Scholar]

- Pelagio-Flores, R.; Ortïz-Castro, R.; Méndez-Bravo, A.; Macïas-Rodrïguez, L.; López-Bucio, J. Serotonin a tryptophan-derived signal conserved in plants and animals regulates root system architecture probably acting as a natural auxin inhibitor in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 2011, 52, 490–508. [Google Scholar]

- Pelagio-Flores, R.; Muñoz-Parra, E.; Ortiz-Castro, R.; López-Bucio, J. Melatonin regulates Arabidopsis root system architecture likely acting independently of auxin signaling. J. Pineal Res 2012, 53, 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Back, K. Melatonin promotes seminal root elongation and root growth in transgenic rice after germination. J. Pineal Res 2012, 53, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, H.M.; Chiu, J.; Hsieh, M.H.; Meisel, L.; Oliveira, I.C.; Shin, M.; Coruzzi, G. Glutamate-receptor genes in plants. Nature 1998, 396, 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Turano, F.J.; Panta, G.R.; Allard, M.W.; van Berkum, P. The putative glutamate receptors from plants are related to two superfamilies of animal neurotransmitter receptors via distinct evolutionary mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Evol 2001, 18, 1417–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Price, M.B.; Jelesko, J.; Okumoto, S. Glutamate receptor homologs in plants: Functions and evolutionary origins. Front. Plant Sci 2012, 3, 235. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Mancuso, S. Root apex transition zone as oscillatory zone. Front. Plant Sci 2013, 4, 354. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, M.J. Evidence for the regulation of phytochrome-mediated processes in bean roots by the neurohumor acetylcholine. Plant Physiol 1970, 46, 768–777. [Google Scholar]

- Tanada, T. On the involvement of acetylcholine in phytochrome action. Plant Physiol 1972, 49, 860–861. [Google Scholar]

- Bossen, M.E.; Tretyn, A.; Kendrick, R.E.; Vredenberg, W.J. Comparison between swelling of etiolated wheat (Triticum aestivum L) protoplasts induced by phytochrome and α-naphthaleneacetic acid benzylaminopurine gibberellic acid abscisic acid and acetylcholine. J. Plant Physiol 1991, 137, 706–710. [Google Scholar]

- Wessler, I.; Kilbinger, H.; Bittinger, F.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. The non-neuronal cholinergic system: The biological role of non-neuronal acetylcholine in plants and humans. Jpn. J. Pharmacol 2001, 85, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tretyn, A.; Bossen, M.E.; Kendrick, R.E. The influence of acetylcholine on the swelling of wheat (Triticum aestivum L) protoplasts. J. Plant Physiol 1990, 136, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tretyn, A.; Kendrick, R.E.; Bossen, M.E.; Vredenberg, W.J. Influence of acetylcholine agonists and antagonists on the swelling of etiolated wheat (Triticum aestivum L) mesophyll protoplasts. Planta 1990, 182, 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Lou, C. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is involved in acetylcholine regulating of stomatal movement. Sci. China Ser. C 1998, 41, 650–656. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Lou, C. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor involved in acetylcholine regulating of stomatal function. Chin. Sci. Bull 2000, 45, 250–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Lou, C. Role of acetylcholine on plant root-shoot signal transduction. Chin. Sci. Bull 2003, 48, 570–573. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.L. Promotion of cell elongation in avena coleoptiles by acetylcholine. Plant Physiol 1972, 50, 414–416. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, V.R.; Brady, R.M.; Campbell, A.; Knox, B.G.; Knox, G.D.; Walls, R.L. Interaction of acetylcholine chloride with IAA GA3 and red light in the growth of excised apical coleoptile segments. B. Torrey Bot. Club 1978, 105, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature 2000, 407, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Català, C.; Rose, J.K.C.; Bennett, A.B. Auxin regulation and spatial localization of an endo-14-β-d-glucanase and a xyloglucan endotransglycosylase in expanding tomato hypocotyls. Plant J 1997, 12, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Caderas, D.; Muster, M.; Vogler, H.; Mandel, T.; Rose, J.K.C.; McQueen-Mason, S.; Kuhlemeier, C. Limited correlation between expansin gene expression and elongation growth rate. Plant Physiol 2000, 123, 1399–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Arru, L.; Rognoni, S.; Poggi, A.; Loreti, E. Effect of sugars on auxin-mediated LeEXPA2 gene expression. Plant Growth Regul 2008, 55, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, F.; Baena-Gonzalez, E.; Sheen, J. Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: Conserved and novel mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol 2006, 57, 675–709. [Google Scholar]

- Eveland, A.L.; Jackson, D.P. Sugars signalling and plant development. J. Exp. Bot 2012, 63, 3367–3377. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, P.G.; Frankel, N.; Mazuch, J.; Balbo, I.; Iusem, N.; Fernie, A.R.; Carrari, F. ASR1 mediates glucose-hormone cross talk by affecting sugar trafficking in tobacco plants. Plant Physiol 2013, 161, 1486–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, S.I. Control of plant development and gene expression by sugar signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 2005, 8, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Baena-González, E.; Sheen, J. Convergent energy and stress signaling. Trends Plant. Sci 2008, 13, 474–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J.; Smeekens, S. Sugar perception and signaling: an update. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol 2009, 12, 562–567. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam, M.R.B.; van den Ende, W. Sugars the clock and transition to flowering. Front. Plant Sci 2013, 4, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.H.; Taylor, P. Muscarinic receptor agonists and antagonists. In Goodman & Gilman’s the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 11th ed.; Brunton, L.L., Lazo, J.S., Parker, K.L., Eds.; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 183–216. [Google Scholar]

- Westfall, T.C.; Westfall, D.P. Neurotransmission: The autonomic and somatic motor nervous systems. In Goodman & Gilman’s the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 11th ed.; Brunton, L.L., Lazo, J.S., Parker, K.L., Eds.; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 137–181. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, O.K.; Moore, I. An ARF-GEF acting at the Golgi and in selective endocytosis in polarized plant cells. Nature 2007, 448, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.G.; Langhans, M.; Saint-Jore-Dupas, C.; Hawes, C. BFA effects are tissue and not just plant specific. Trends Plant Sci 2008, 13, 405–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Ruan, Y.L. Unraveling mechanisms of cell expansion linking solute transport metabolism plasmodesmtal gating and cell wall dynamics. Plant Signal. Behav 2010, 5, 1561–1564. [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis, M.; Bleve, G.; Faraco, M.; Stigliano, E.; Grieco, F.; Piro, G.; Dalessandro, G.; di Sansebastiano, G.P. AtSYP51/52 functions diverge in the post-Golgi traffic and differently affect vacuolar sorting. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 916–930. [Google Scholar]

- Stigliano, E.; Faraco, M.; Neuhaus, J.M.; Montefusco, A.; Dalessandro, G.; Piro, G.; di Sansebastiano, G.P. Two glycosylated vacuolar GFPs are new markers for ER-to-vacuole sorting. Plant Physiol. Biochem 2013, 73, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason, S.; Durachko, D.M.; Cosgrove, D.J. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plants. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Soltys, D.; Rudzińska-Langwald, A.; Gniazdowska, A.; Wiśniewska, A.; Bogatek, R. Inhibition of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L) root growth by cyanamide is due to altered cell division phytohormone balance and expansin gene expression. Planta 2012, 236, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.S.; Lee, Y.; Cho, H.T.; Kende, H. Regulation of expansin gene expression affects growth and development in transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1386–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, J.; Backhaus, A.; Malinowski, R.; McQueen-Mason, S.; Fleming, A.J. Phased control of expansin activity during leaf development identifies a sensitivity window for expansin-mediated induction of leaf growth. Plant Physiol 2009, 151, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J.K.C.; Cosgrove, D.J.; Albersheim, P.; Darvill, A.G.; Bennett, A.B. Detection of expansin proteins and activity during tomato ontogeny. Plant Physiol 2000, 123, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar]

- Zenoni, S.; Fasoli, M.; Tornielli, G.B.; Santo, S.D.; Sanson, A.; Groot, P.; Sordo, S.; Citterio, S.; Monti, F.; Pezzotti, M. Overexpression of PhEXPA1 increases cell size modifies cell wall polymer composition and affects the timing of axillary meristem development in Petunia hybrida. New Phytol 2011, 191, 662–677. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J.K.C.; Lee, H.H.; Bennet, A.B. Expression of a divergent expansin gene is fruit-specific and ripening regulated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 5955–5960. [Google Scholar]

- Brummell, D.A.; Harpster, M.H.; Dunsmuir, P. Differential expression of expansin gene family members during growth and ripening of tomato fruit. Plant Mol. Biol 1999, 39, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Bradford, K.J. Expression of an expansin is associated with endosperm weakening during tomato seed germination. Plant Physiol 2000, 124, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, D.; Wittwer, F.; Mandel, T.; Kuhlemeier, C. Localized upregulation of a new expansin gene predicts the site of leaf formation in the tomato meristem. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Catalá, C.; Rose, J.K.C.; Bennett, A.B. Auxin-regulated genes encoding cell wall-modifying proteins are expressed during early tomato fruit growth. Plant Physiol 2000, 122, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, H.; Nirasawa, S.; Terauchi, R. Transcript profiling in rice (Oryza sativa L) seedlings using serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE). Plant J 1999, 20, 719–726. [Google Scholar]

- Harb, A.; Krishnan, A.; Ambavaram, M.M.R.; Pereira, A. Molecular and physiological analysis of drought stress in Arabidopsis reveals early responses leading to acclimation in plant growth. Plant Physiol 2010, 154, 1254–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, P.; Kang, M.; Jiang, X.; Dai, F.; Gao, J.; Zhang, C. RhEXPA4 a rose expansin gene modulates leaf growth and confers drought and salt tolerance to Arabidopsis. Planta 2013, 237, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, K.W.; Singer, P.B.; McInnis, S.; Diaz-Sala, C.; Greenwood, M.S. Expansins are conserved in conifers and expressed in hypocotyls in response to exogenous auxin. Plant Physiol 1999, 120, 827–831. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.T.; Kende, H. Expression of expansin genes is correlated with growth in deepwater rice. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Kende, H. Expression of b-expansins is correlated with internodal elongation in deepwater rice. Plant Physiol 2001, 127, 645–654. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, R.C.; Lynn, D.G. Expansin message regulation in parasitic angiosperms: Marking time in development. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel, R.L.; Yoder, J.I. Differential RNA expression of α-expansin gene family members in the parasitic angiosperm Triphysaria versicolor (Scrophulariaceae). Gene 2001, 266, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Cho, H.T.; Kende, H. α-Expansins in the semi-aquatic ferns Marsilea quadrifolia and Regnellidium diphyllum: Evolutionary aspects and physiological role in rachis elongation. Planta 2000, 212, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Vriezen, W.H.; de Graaf, B.; Mariani, C.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J. Submergence induces expansin gene expression in flooding-tolerant Rumex palustris and not in flooding-intolerant R. acetosa. Planta 2000, 210, 956–963. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, A.; Elzinga, N.; Wobbes, B.; Smeekens, S. Sucrose-induced translational repression of plant bZIP-type transcription factors. Biochem. Soc. Trans 2005, 33, 272–275. [Google Scholar]

- Wind, J.; Smeekens, S.; Hanson, J. Sucrose: Metabolite and signaling molecule. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1610–1614. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y.L. Signaling role of sucrose metabolism in development. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 763–765. [Google Scholar]

- Tognetti, J.A.; Pontis, H.G.; Noël, G.M.M. Sucrose signaling in plants: A world yet to be explored. Plant Signal. Behav 2013, 8, e23316:1–e23315:10. [Google Scholar]

- Bamel, K.; Chandra Gupta, S.; Gupta, R. Acetylcholine causes rooting in leaf explants of in vitro raised tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Miller) seedlings. Life Sci 2007, 80, 2393–2396. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, K.I.; Tezuka, T. Acetylcholine promotes the emergence and elongation of lateral roots of Raphanus sativus. Plant Signal. Behav 2011, 6, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Roshchina, V.V.; Mukhin, E.N. Acetylcholine action on the photochemical reactions of pea chloroplasts. Plant Sci 1985, 42, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tretyni, A.; Bossen, M.E.; Kendrick, R.E. Evidence for different types of acetylcholine receptors in plants. In Progress in Plant Growth Regulation; Karssen, C.M., van Loon, L.C., Vreugdenhil, D., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 306–311. [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi, Y.; Kimura, R.; Kato, N.; Fujii, T.; Seki, M.; Endo, T.; Kato, T.; Kawashima, K. Evolutional study on acetylcholine expression. Life Sci 2003, 72, 1745–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, K.; Misawa, H.; Moriwaki, Y.; Fujii, Y.X.; Fujii, T.; Horiuchi, Y.; Yamadaa, T.; Imanaka, T.; Kamekura, M. Ubiquitous expression of acetylcholine and its biological functions in life forms without nervous systems. Life Sci 2007, 80, 2206–2209. [Google Scholar]

- Bouche, N.; Lacombe, B.; Fromm, H. GABA signaling: A conserved and ubiquitous mechanism. Trends Cell Biol 2003, 13, 607–610. [Google Scholar]

- Craxton, M. Synaptotagmin gene content of the sequenced genomes. BMC Genomics 2004, 5, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, E.D. Drugs in the plant. Cell 2002, 109, 680–681. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška, F.; Hlavacka, A.; Mancuso, S.; Volkmann, D.; Barlow, P.W. Neurobiological view of plants and their body plan. In Communication in Plants—Neuronal Aspects of Plant Life; Baluška, F., Mancuso, S., Volkmann, D., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Forde, B.G. Glutamate signalling in roots. J. Exp. Bot 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljung, K. Auxin metabolism and homeostasis during plant development. Development 2013, 140, 943–950. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson, U.; Riedl, M.; Elde, R.; Meister, B. Vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) protein: A novel and unique marker for cholinergic neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J. Comp. Neurol 1997, 378, 454–467. [Google Scholar]

- Guiheneuc, P. Neuromuscular synapse: Molecular mechanisms of acetylcholine vesicular exocytosis. Ann. Readapt. Med. Phys 2003, 46, 276–280. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, V.F.; Roy, A.; Kolisnyk, B.; Gros, R.; Prado, M.A. Regulation of cholinergic activity by the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Biochem. J 2013, 450, 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Faraco, M.; di Sansebastiano, G.P.; Spelt, K.; Koes, R.E.; Quattrocchio, F.M. One protoplast is not the other! Plant Physiol 2011, 156, 474–478. [Google Scholar]

- Denecke, J.; Aniento, F.; Frigerio, L.; Hawes, C.; Hwang, I.; Mathur, J.; Neuhaus, J.M.; Robinson, D.G. Secretory pathway research: The more experimental systems the better. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocchio, F.M.; Spelt, C.; Koes, R. Transgenes and protein localization: myths and legends. Trends Plant Sci 2013, 18, 473–476. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sansebastiano, G.P.; Paris, N.; Marc-Martin, S.; Neuhaus, J.M. Regeneration of a lytic central vacuole and of neutral peripheral vacuoles can be visualized by green fluorescent proteins targeted to either type of vacuoles. Plant Physiol 2001, 126, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bolte, S.; Talbot, C.; Boutte, Y.; Catrice, O.; Read, N.D.; Satiat-Jeunemaitre, B. FM-dyes as experimental probes for dissecting vesicle trafficking in living plant cells. J. Microsc 2004, 214, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- De Caroli, M.; Lenucci, M.S.; di Sansebastiano, G.P.; Dalessandro, G.; de Lorenzo, G.; Piro, G. Protein trafficking to the cell wall occurs through mechanisms distinguishable from default sorting in tobacco. Plant J 2011, 65, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- De Caroli, M.; Lenucci, M.S.; di Sansebastiano, G.P.; Dalessandro, G.; de Lorenzo, G.; Piro, G. Dynamic protein trafficking to the cell wall. Plant Signal. Behav 2011, 6, 1012–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Geldner, N.; Anders, N.; Wolters, H.; Keicher, J.; Kornberger, W.; Muller, P.; Delbarre, A.; Ueda, T.; Nakano, A.; Jürgens, G. The Arabidopsis GNOM ARF-GEF mediates endosomal recycling auxin transport and auxin-dependent plant growth. Cell 2003, 112, 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Galván-Ampudia, C.S.; Demarsy, E.; Łangowski, Ł; Kleine-Vehn, J.; Fan, Y.; Morita, M.T.; Tasaka, M.; Fankhauser, C.; Offringa, R.; et al. Light-mediated polarization of the PIN3 auxin transporter for the phototropic response in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol 2011, 13, 447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine-Vehn, J.; Dhonukshe, P.; Swarup, R.; Bennett, M.; Friml, J. Subcellular trafficking of the Arabidopsis auxin influx carrier AUX1 uses a novel pathway distinct from PIN1. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 3171–3181. [Google Scholar]

- Geldner, N.; Dénervaud-Tendon, V.; Hyman, D.L.; Mayer, U.; Stierhof, Y.D.; Chory, J. Rapid combinatorial analysis of membrane compartments in intact plants with a multicolor marker set. Plant J 2009, 59, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Drakakaki, G.; Robert, S.; Raikhel, N.V.; Hicks, G.R. Chemical dissection of endosomal pathways. Plant Signal. Behav 2009, 4, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Di Sansebastiano, G.P.; Renna, L.; Gigante, M.; de Caroli, M.; Piro, G.; Dalessandro, G. Green fluorescent protein reveals variability in vacuoles of three plant species. Biol. Plant 2007, 51, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, A.M.; Yakovlev, I.A.; Strauss, S.H. Validating internal controls for quantitative plant gene expression studies. BMC Plant Biol 2004, 4, 14. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).