Structural Biology of the TNFα Antagonists Used in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. TNFα Antagonists for the Treatment of Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases

3. Interactions between TNFα and FDA-Approved TNFα Antagonists

4. Selectivity of TNFα Antagonists against Lymphotoxin α

5. Structural Rigidity of the CDR Loops within Anti-TNFα Antibodies

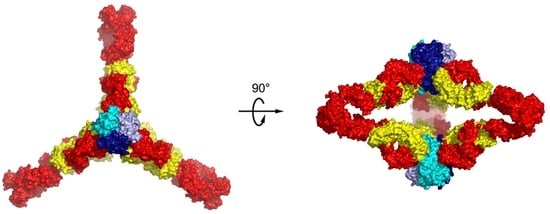

6. Higher Order Structures of Antibody-TNFα Complexes

7. The Quinary Structure of Infliximab

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Locksley, R.M.; Killeen, N.; Lenardo, M.J. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: Integrating mammalian biology. Cell 2001, 104, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, G.D.; Glenney, G.W. Origin and evolution of TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 1324–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Goeddel, D.V. TNF-R1 signaling: A beautiful pathway. Science 2002, 296, 1634–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennica, D.; Nedwin, G.E.; Hayflick, J.S.; Seeburg, P.H.; Derynck, R.; Palladino, M.A.; Kohr, W.J.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Goeddel, D.V. Human tumor necrosis factor: Precursor structure, cDNA cloning, expression, and homology to lymphotoxin. Nature 1984, 312, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luettiq, B.; Decker, T.; Lohmann-Matthes, M.L. Evidence for the existence of two forms of membrane tumor necrosis factor: An integral protein and a molecule attached to its receptor. J. Immunol. 1989, 143, 4034–4038. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegler, M.; Perez, C.; DeFay, K.; Albert, I.; Lu, S.D. A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: Ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF. Cell 1988, 53, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, P.; Declercq, W.; Beyaert, R.; Fiers, W. Two tumour necrosis factor receptors: Structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 1995, 5, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoni, F.; Beutler, B. The tumor necrosis factor ligand and receptor families. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1717–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, R.A.; Rauch, C.T.; Kozlosky, C.J.; Peschon, J.J.; Slack, J.L.; Wolfson, M.F.; Castner, B.J.; Stocking, K.L.; Reddy, P.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature 1997, 385, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, M.L.; Jin, S.-L.C.; Milla, M.E.; Burkhart, W.; Carter, H.L.; Chen, W.-J.; Clay, W.C.; Didsbury, J.R.; Hassler, D.; Hoffman, C.R.; et al. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature 1997, 385, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, M.J.; Maini, R.N.; Feldmann, M.; Kalden, J.R.; Antoni, C.; Smolen, J.S.; Leeb, B.; Breedveld, F.C.; Macfarlane, J.D.; Bijl, J.A.; et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor alpha (cA2) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1994, 344, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinblatt, M.E.; Keystone, E.C.; Furst, D.E.; Moreland, L.W.; Weisman, M.H.; Birbara, C.A.; Teoh, L.A.; Fischkoff, S.A.; Chartash, E.K. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: The ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanauer, S.B.; Sandborn, W.J.; Rutgeerts, P.; Fedorak, R.N.; Lukas, M.; MacIntosh, D.; Panaccione, R.; Wolf, D.; Pollack, P. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: The CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdaca, G.; Colombo, B.M.; Cagnati, P.; Gulli, R.; Spanò, F.; Puppo, F. Update upon efficacy and safety of TNF-alpha inhibitors. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2012, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducharme, E.; Weinberg, J.M. Etanercept. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2008, 8, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, P.C. Pharmacology of TNF blockade in rheumatoid arthritis and other chronic inflammatory diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010, 10, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Simone, C.; Amerio, P.; Amoruso, G.; Bardazzi, F.; Campanati, A.; Conti, A.; Gisondi, P.; Gualdi, G.; Guarneri, C.; Leoni, L.; et al. Immunogenicity of anti-TNFα therapy in psoriasis: A clinical issue? Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2013, 13, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.D.; Keystone, E.C. Intravenous golimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 10, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeks, E.D. Certolizumab Pegol: A Review in Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases. BioDrugs 2016, 30, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitoma, H.; Horiuchi, T.; Tsukamoto, H.; Ueda, N. Molecular mechanisms of action of anti-TNF-α agents—Comparison among therapeutic TNF-α antagonists. Cytokine 2018, 101, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, T.; Mitoma, H.; Harashima, S.; Tsukamoto, H.; Shimoda, T. Transmembrane TNF-alpha: Structure, function and interaction with anti-TNF agents. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010, 49, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scallon, B.; Cai, A.; Solowski, N.; Rosenberg, A.; Song, X.Y.; Shealy, D.; Wagner, C. Binding and functional comparisons of two types of tumor necrosis factor antagonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 301, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringheanu, M.; Daum, F.; Markowitz, J.; Levine, J.; Katz, S.; Lin, X.; Silver, J. Effects of infliximab on apoptosis and reverse signaling of monocytes from healthy individuals and patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2004, 10, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitoma, H.; Horiuchi, T.; Tsukamoto, H.; Tamimoto, Y.; Kimoto, Y.; Uchino, A.; To, K.; Harashima, S.; Hatta, N.; Harada, M. Mechanisms for cytotoxic effects of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents on transmembrane tumor necrosis factor alpha-expressing cells: Comparison among infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Brande, J.M.; Braat, H.; van den Brink, G.R.; Versteeg, H.H.; Bauer, C.A.; Hoedemaeker, I.; van Montfrans, C.; Hommes, D.W.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; van Deventer, S.J. Infliximab but not etanercept induces apoptosis in lamina propria T-lymphocytes from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, A.; Fossati, G.; Bergin, M.; Stephens, P.; Stephens, S.; Foulkes, R.; Brown, D.; Robinson, M.; Bourne, T. Mechanism of action of certolizumab pegol (CDP870): In vitro comparison with other anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007, 13, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitoma, H.; Horiuchi, T.; Hatta, N.; Tsukamoto, H.; Harashima, S.-I.; Kikuchi, Y.; Otsuka, J.; Okamura, S.; Fujita, S.; Harada, M. Infliximab induces potent anti-inflammatory responses by outside-to-inside signals through transmembrane TNF-alpha. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaymakcalan, Z.; Sakorafas, P.; Bose, S.; Scesney, S.; Xiong, L.; Hanzatian, D.K.; Salfeld, J.; Sasso, E.H. Comparisons of affinities, avidities, and complement activation of adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept in binding to soluble and membrane tumor necrosis factor. Clin. Immunol. 2009, 131, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shealy, D.J.; Cai, A.; Staquet, K.; Baker, A.; Lacy, E.R.; Johns, L.; Vafa, O.; Gunn, G.; Tam, S.; Sague, S.; et al. Characterization of golimumab, a human monoclonal antibody specific for human tumor necrosis factor α. MAbs 2010, 2, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, A.C.; Wildenberg, M.E.; Duijvestein, M.; Verhaar, A.P.; van den Brink, G.R.; Hommes, D.W. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies induce regulatory macrophages in an Fc region-dependent manner. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtal, K.A.; Rogler, G.; Scharl, M.; Biedermann, L.; Frei, P.; Fried, M.; Weber, A.; Eloranta, J.J.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Vavricka, S.R. Fc gamma receptor CD64 modulates the inhibitory activity of infliximab. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ueda, N.; Tsukamoto, H.; Mitoma, H.; Ayano, M.; Tanaka, A.; Ohta, S.; Inoue, Y.; Arinobu, Y.; Niiro, H.; Akashi, K.; et al. The cytotoxic effects of certolizumab pegol and golimumab mediated by transmembrane tumor necrosis factor α. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derer, S.; Till, A.; Haesler, R.; Sina, C.; Grabe, N.; Jung, S.; Nikolaus, S.; Kuehbacher, T.; Groetzinger, J.; Rose-John, S.; et al. mTNF reverse signalling induced by TNFα antagonists involves a GDF-1 dependent pathway: Implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut 2013, 62, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubel, J.S.; Testro, A.G.; Angus, P.W. Hepatitis B virus reactivation following immunosuppressive therapy: Guidelines for prevention and management. Intern. Med. J. 2007, 37, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Reino, J.J.; Carmona, L.; Valverde, V.R.; Mola, E.M.; Montero, M.D.; BIOBADASER Group. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may predispose to significant increase in tuberculosis risk: A multicenter active-surveillance report. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 2122–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.L.; Greene, M.H.; Gershon, S.K.; Edwards, E.T.; Braun, M.M. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy and lymphoma development: Twenty-six cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 3151–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banner, D.W.; D’Arcy, A.; Janes, W.; Gentz, R.; Schoenfeld, H.J.; Broger, C.; Loetscher, H.; Lesslauer, W. Crystal structure of the soluble human 55 kd TNF receptor-human TNF beta complex: Implications for TNF receptor activation. Cell 1993, 73, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yoshioka, Y.; Tsunoda, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Yamagata, Y.; Tsutsumi, Y. Solution of the structure of the TNF-TNFR2 complex. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Dai, J.; Hou, S.; Su, L.; Zhang, D.; Guo, H.; Hu, S.; Wang, H.; Rao, Z.; Guo, Y.; et al. Structural basis for treating tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-associated diseases with the therapeutic antibody infliximab. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 13799–13807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Liang, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Qian, W.; Hou, S.; Wang, H.; et al. Comparison of the inhibition mechanisms of adalimumab and infliximab in treating tumor necrosis factor α-associated diseases from a molecular view. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 27059–27067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.U.; Shin, W.; Son, J.Y.; Yoo, K.Y.; Heo, Y.S. Molecular Basis for the Neutralization of Tumor Necrosis Factor α by Certolizumab Pegol in the Treatment of Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerch, T.F.; Sharpe, P.; Mayclin, S.J.; Edwards, T.E.; Lee, E.; Conlon, H.D.; Polleck, S.; Rouse, J.C.; Luo, Y.; Zou, Q. Infliximab crystal structures reveal insights into self-association. MAbs 2017, 9, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Long, D.S.; Lute, S.C.; Levy, M.J.; Brorson, K.A.; Keire, D.A. Simple NMR methods for evaluating higher order structures of monoclonal antibody therapeutics with quinary structure. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 128, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, B.N.; Chan, S.L.; Ng, C.; Shi, J.; Correia, I.; Radziejewski, C.; Matsudaira, P. Higher order structures of Adalimumab, Infliximab and their complexes with TNFα revealed by electron microscopy. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 2392–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, C.; Sancetta, R.; Cerutti, A.; Semenzato, G. Alveolar macrophages as a cell source of cytokine hyperproduction in HIV-related interstitial lung disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995, 58, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caron, G.; Delneste, Y.; Aubry, J.P.; Magistrelli, G.; Herbault, N.; Blaecke, A.; Meager, A.; Bonnefoy, J.Y.; Jeannin, P. Human NK cells constitutively express membrane TNF-alpha (mTNFalpha) and present mTNFalpha-dependent cytotoxic activity. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999, 29, 3588–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, M. Cytolytic activities of activated macrophages versus paraformaldehyde-fixed macrophages; soluble versus membrane-associated TNF. Cell Immunol. 1991, 137, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L.; Thickett, D.R.; Christie, S.J.; Kendall, H.; Millar, A.B. Increased expression of functionally active membrane-associated tumor necrosis factor in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000, 22, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, M.; Latta, M.; Künstle, G.; Riehle, H.M.; van Rooijen, N.; Hentze, H.; Tiegs, G.; Biburger, M.; Lucas, R.; Wendel, A. Kupffer cell-expressed membrane-bound TNF mediates melphalan hepatotoxicity via activation of both TNF receptors. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 4076–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck, R.; Brockhaus, M.; Frey, J.R. Cell surface tumor necrosis factor (TNF) accounts for monocyte- and lymphocyte-mediated killing of TNF-resistant target cells. Cell Immunol. 1989, 122, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, T.; Morita, C.; Tsukamoto, H.; Mitoma, H.; Sawabe, T.; Harashima, S.; Kashiwagi, Y.; Okamura, S. Increased expression of membrane TNF-alpha on activated peripheral CD8+ T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 17, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grell, M.; Douni, E.; Wajant, H.; Löhden, M.; Clauss, M.; Maxeiner, B.; Georgopoulos, S.; Lesslauer, W.; Kollias, G.; Pfizenmaier, K.; et al. The transmembrane form of tumor necrosis factor is the prime activating ligand of the 80 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell 1995, 83, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, D.; Klareskog, L.; Sasso, E.H.; Salfeld, J.G.; Tak, P.P. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist mechanisms of action: A comprehensive review. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 117, 244–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, D.R.; Choi, Y. Signaing by tumor necrosis factor receptors: pathways, paradigms and targets for therapeutic modulation. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1999, 18, 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, F.K.; Chun, H.J.; Zheng, L.; Siegel, R.M.; Bui, K.L.; Lenardo, M.J. A domain in TNF receptors that mediates ligand-independent receptor assembly and signaling. Science 2000, 288, 2351–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacEwan, D.J. TNF ligands and receptors-a matter of life and death. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 135, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissner, G.; Kolch, W.; Scheurich, P. Ligands working as receptors: Reverse signaling by members of the TNF superfamily enhance the plasticity of the immune system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004, 15, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivkin, A. Certolizumab pegol for the management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Clin. Ther. 2009, 31, 1158–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, T.; Fossati, G.; Nesbitt, A. A PEGylated Fab’ fragment against tumor necrosis factor for the treatment of Crohn disease: Exploring a new mechanism of action. BioDrugs 2008, 22, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasut, G. Pegylation of biological molecules and potential benefits: Pharmacological properties of certolizumab pegol. BioDrugs 2014, 28 (Suppl. 1), S15–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, T.; Padaki, R.; Liu, L.; Hamburger, A.E.; Ellison, A.R.; Stevens, S.R.; Louie, J.S.; Kohno, T. Differences in binding and effector functions between classes of TNF antagonists. Cytokine 2009, 45, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lis, K.; Kuzawińska, O.; Bałkowiec-Iskra, E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors—State of knowledge. Arch. Med. Sci. 2014, 10, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narhi, L.O.; Arakawa, T. Dissociation of recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α studied by gel permeation chromatography. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987, 147, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, A.; Fassina, G.; Marcucci, F.; Barbanti, E.; Cassani, G. Oligomeric tumour necrosis factor α slowly converts into inactive forms at bioactive levels. Biochem. J. 1992, 284, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlodan, R.; Pain, R.H. The folding and assembly pathway of tumour necrosis factor TNFα, a globular trimeric protein. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 231, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Schie, K.A.; Ooijevaar-de Heer, P.; Dijk, L.; Kruithof, S.; Wolbink, G.; Rispens, T. Therapeutic TNF inhibitors can differentially stabilize trimeric TNF by inhibiting monomer exchange. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, J.L.; Miatkowski, K.; Griffiths, D.A.; Bourdon, P.R.; Hession, C.; Ambrose, C.M.; Meier, W. Preparation and characterization of soluble recombinant heterotrimeric complexes of human lymphotoxins alpha and beta. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 8618–8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calmon-Hamaty, F.; Combe, B.; Hahne, M.; Morel, J. Lymphotoxin α stimulates proliferation and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion of rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Cytokine 2011, 53, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrmann, C.; Shayan, P.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Shakibaei, M. Evidence that TNF-β (lymphotoxin α) can activate the inflammatory environment in human chondrocytes. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15, R202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.C. Accessing the Kabat antibody sequence database by computer. Proteins 1996, 25, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.A.; Stanfield, R.L. Antibody-antigen interactions: New structures and new conformational changes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1994, 4, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, T.; Tam, L.T.; Stevens, S.R.; Louie, J.S. Binding characteristics of tumor necrosis factor receptor-Fc fusion proteins vs anti-tumor necrosis factor mAbs. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2007, 12, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santora, L.C.; Kaymakcalan, Z.; Sakorafas, P.; Krull, I.S.; Grant, K. Characterization of noncovalent complexes of recombinant human monoclonal antibody and antigen using cation exchange, size exclusion chromatography, and BIAcore. Anal. Biochem. 2001, 299, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalonia, C.; Toprani, V.; Toth, R.; Wahome, N.; Gabel, I.; Middaugh, C.R.; Volkin, D.B. Effects of Protein Conformation, Apparent Solubility, and Protein-Protein Interactions on the Rates and Mechanisms of Aggregation for an IgG1Monoclonal Antibody. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 7062–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Guo, H.; Xu, J.; Qin, T.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, D.; Qian, W.; Li, B.; et al. Acid-induced aggregation propensity of nivolumab is dependent on the Fc. MAbs 2016, 8, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TNFα Antagonist | Original Product | Biosimilar Product | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etanercept | Enbrel® (1998) | Erelzi® (2016) | TNFR2 ectodomain fused to IgG1 Fc |

| Infliximab | Remicade® (1998) | Inflectra® (2016), Ixifi® (2017) | Chimeric murine/human IgG1 |

| Adalimumab | Humira® (2002) | Amjevita® (2016), Cyltezo® (2017) | Fully Human IgG1 |

| Certolizumab-pegol | Cimzia® (2008) | Humanized, PEGylated Fab’ | |

| Golimumab | Simponi® (2009) | Fully Human IgG1 |

| TNFα Antagonist | Protein/Complex | Method | PDB ID | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etanercept | TNFR2 ectodomain in complex with TNFα | X-ray | 3ALQ | [38] |

| Infliximab | Fab fragment in complex with TNFα | X-ray | 4G3Y | [39] |

| Fab fragment | X-ray | 5VH3 | [42] | |

| Fab fragment | X-ray | 5VH4 | [42] | |

| Fc fragment | X-ray | 5VH5 | [42] | |

| 1:1, 1:2, 2:2, 3:2 complex | Cryo-EM | [44] | ||

| Adalimumab | Fab fragment in complex with TNFα | X-ray | 3WD5 | [40] |

| Fab fragment | X-ray | 4NYL | to be published | |

| 1:1, 1:2, 2:2, 3:2 complex | Cryo-EM | [44] | ||

| Certolizumab-pegol | Fab fragment in complex with TNFα | X-ray | 5WUX | [41] |

| Fab fragment | X-ray | 5WUV | [41] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, H.T.; Lee, J.U.; Son, J.Y.; Shin, W.; Heo, Y.-S. Structural Biology of the TNFα Antagonists Used in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19030768

Lim H, Lee SH, Lee HT, Lee JU, Son JY, Shin W, Heo Y-S. Structural Biology of the TNFα Antagonists Used in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(3):768. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19030768

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Heejin, Sang Hyung Lee, Hyun Tae Lee, Jee Un Lee, Ji Young Son, Woori Shin, and Yong-Seok Heo. 2018. "Structural Biology of the TNFα Antagonists Used in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 3: 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19030768