Resilient Prosumer Scenario in a Changing Regulatory Environment—The UniRCon Solution

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Optimal Integration of Renewables in a Changing Regulatory Environment

2.1. Introduction

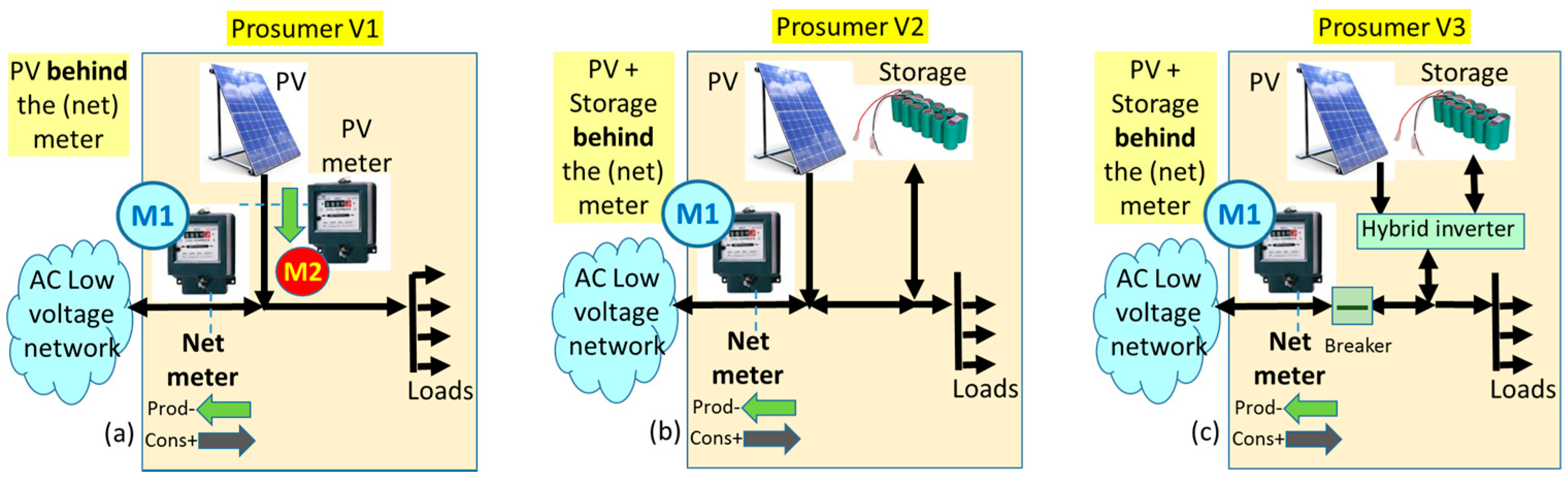

- Prosumer V1 (Figure 2a) has PV (or other intermittent, RES-based) generation behind the meter, connected to both the AC internal network and the DSO grid; depending on secondary legislation, available support scheme such as feed-in tariff (FiT) or green certificates (GC) might apply either for the excess energy measured by the net meter M1, or for the energy measured by the PV meter M2;

- ■

- Advantages: Support schemes apply; installed PV capacity could be greater than the local need (instant power terms), which is an advantage if good support schemes apply.

- ■

- Disadvantages: Income from support schemes is exposed to regulatory changes; curtailment asked by the relevant operator may apply, especially in a high-RES penetration situation.

- Prosumer V2 (Figure 2b) has PV and local storage connected to the AC grid directly operated by the DSO, for example for addressing local power-quality issues.

- ■

- Advantages: Electricity harvested during the day can be stored and used during the evening, thus increasing self-consumption.

- ■

- Disadvantages: Each piece of equipment is connected to the grid as a generation unit, thus being subjected to network requirements and regulatory changes, such as curtailment; according to EU regulation, the generators’ operation is monitored without considering prosumer behaviour.

- Prosumer V3 (Figure 2c) has a device—named a generically hybrid inverter—which connects PV and storage to the AC network; it brings resilience to the loads in the islanding mode of operation.

- ■

- Advantages: One piece of equipment (the hybrid inverter) is optimising the PV and storage energy transfer, which allows better operation of both units; good dimensioning can increase the self-consumption of locally produced energy;

- ■

- Disadvantages: In the islanding mode of operation, loads can be supplied only after breaker disconnection; the hybrid inverter needs to comply with network codes and possible curtailment orders still apply. Thus, this architecture is still prone to regulatory changes. Furthermore, the overall efficiency of a PV-storage system can be improved, as DC resources such as PV and storage are still used through the AC network (lower overall efficiency due to unnecessary AC–DC–AC conversion stages).

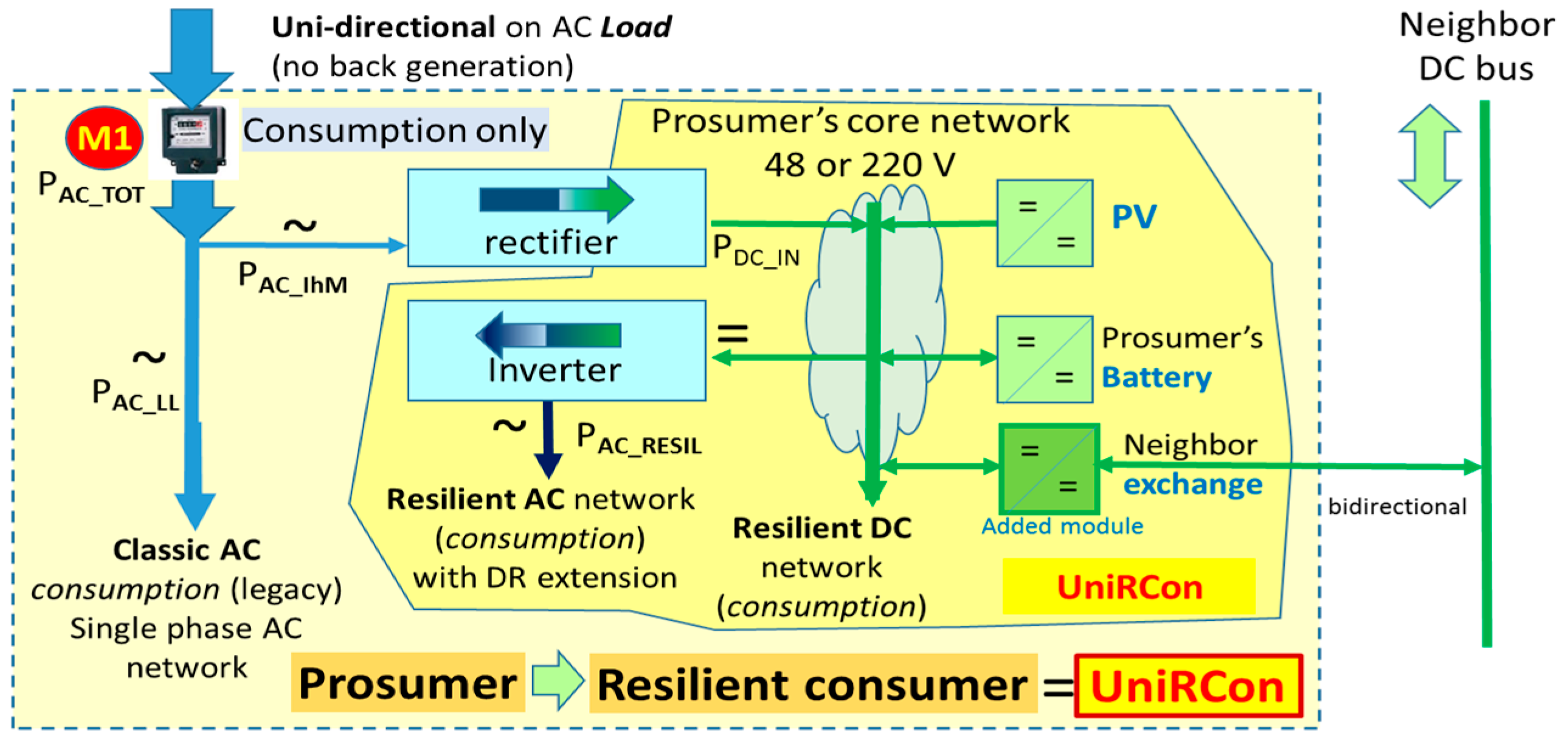

2.2. Resilient Architecture for Prosumers with Integrated Storage

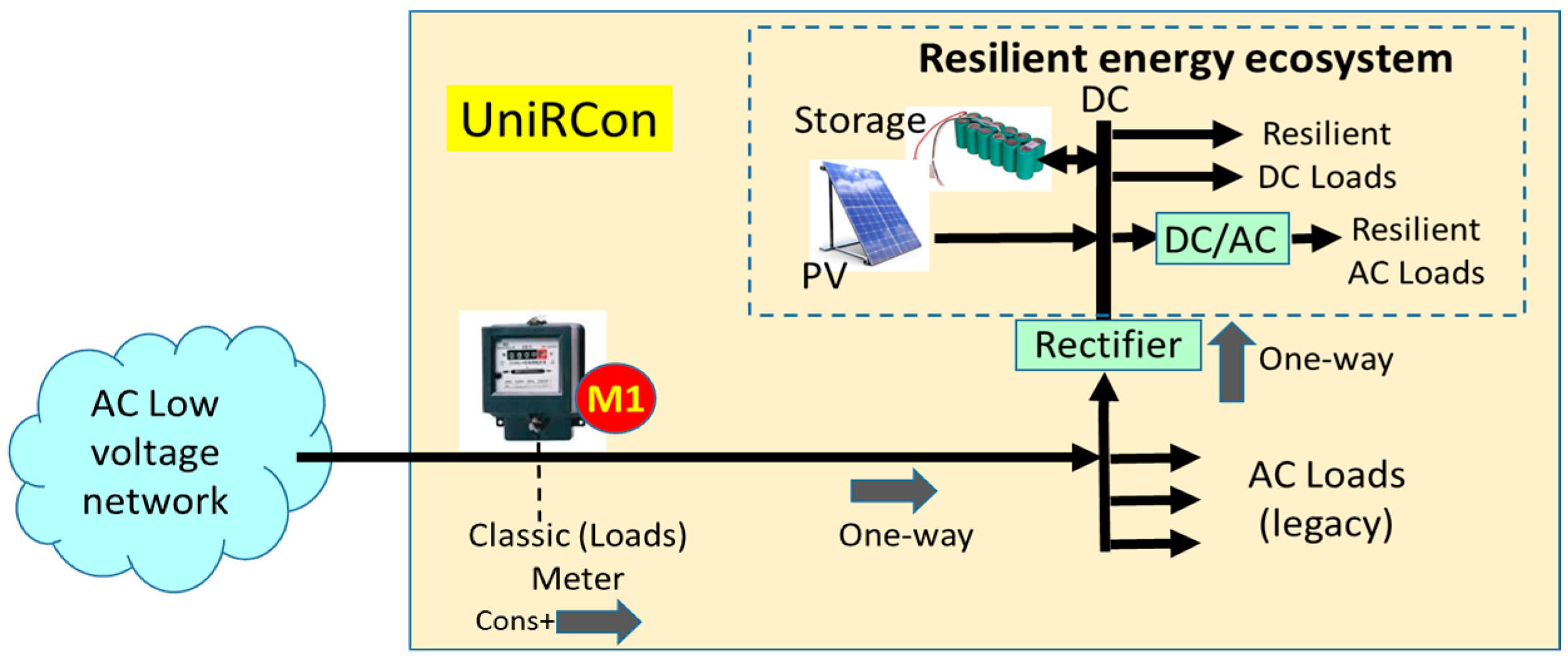

- DSOs will perceive no disruptive operational changes, beyond decreased load profile: an incremental RES-based DG deployment keeps business-as-usual (BAU) load-equivalent behaviour for all new PV owners, thus keeping the grid compatible with its initial design; the proposed prosumer’s grid coupling is more predictable and more flexible, to help the grid in critical situations, and thus enhances options for the DSO to increase its resiliency.

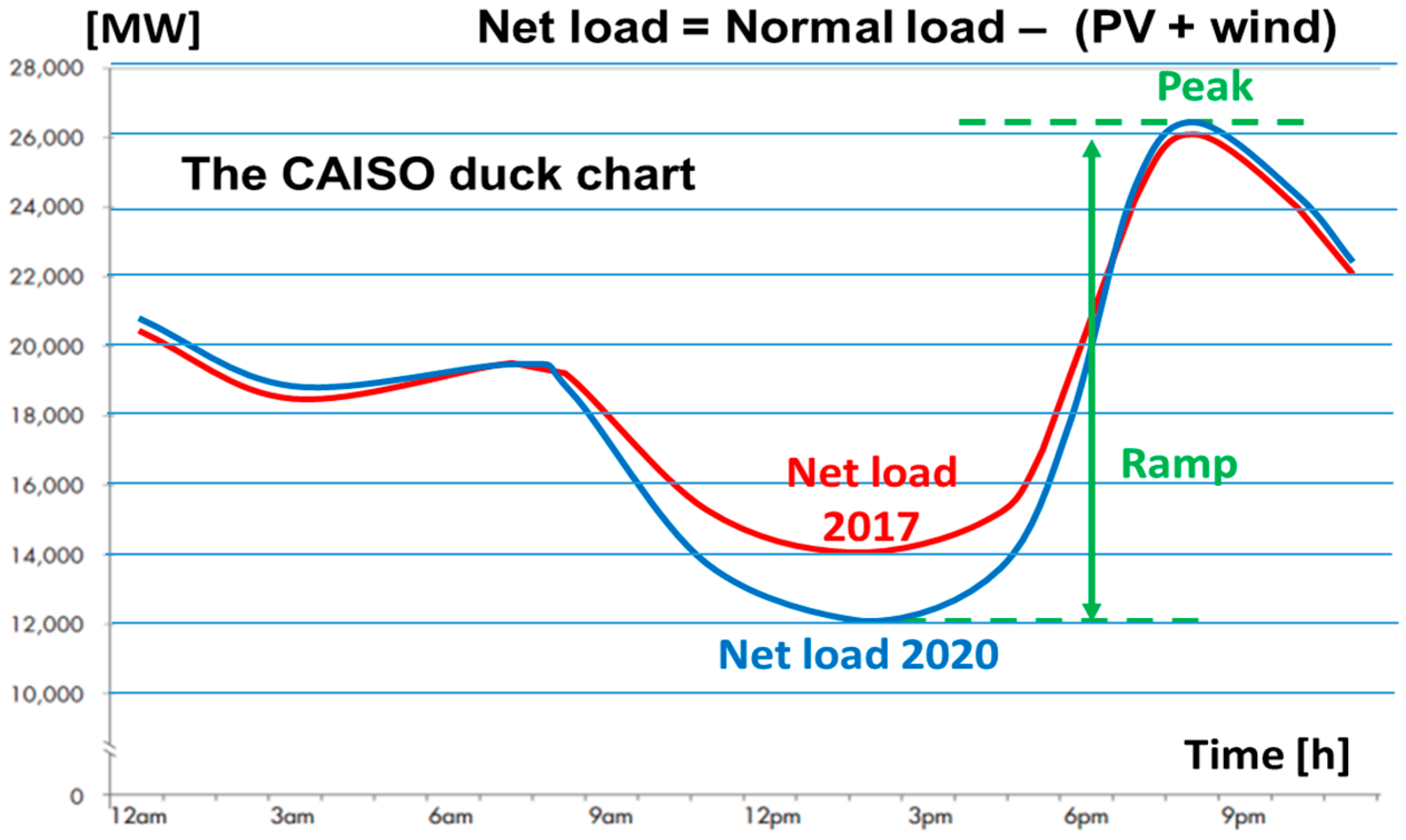

- TSOs will maintain the classic control approach, reducing effects such as duck-chart ramp problem (with the UniRCon grid coupling, there is no un-dispatchable energy production on the TSO side);

- The prosumer will experience:

- ■

- resilience against network outages, due to the prosumer’s internal busbar, which provides by design an independent and adaptable energy and power control algorithm that allows a short- to medium-term islanding operation. Thus, for increasing local resilience, the prosumer may apply scheduling and prioritize consumption based on the available local resources (PV, storage, available energy from neighbourhood connections);

- ■

- stability and predictability in the benefits brought by the RES and storage investment, thus being protected from regulatory changes related to FiT or to curtailment policies (financial resilience);

- ■

- increased self-consumption during summer as well as a high use of market opportunities during winter, when bulk energy can be purchased at low prices; moreover, in winter, storage has higher availability of the capacity due to reduced PV production;

- ■

- higher efficiency of the used energy, as important elements such as PV and storage are naturally functioning in DC and even many of today’s AC loads are also directly pluggable in appropriate DC local grids;

- ■

- lower costs of grid-connection if consumers have the historical right to access electrical energy (a 20th-century electrification paradigm).

- Energy communities in particular will benefit from:

- ■

- higher resiliency, achieved by design due to an additional “backyard DC” network; in addition, higher efficiency of energy use could be achieved by boosting a local energy market, an embryonic model for the new smart cities design;

- Society will benefit from:

- ■

- improved efficiency as a result of energy harvesting and the local use of electricity; this feature was invoked also on the prosumer side, but it has a societal impact as well;

- ■

- preserving participation in a wide-area market like the unified European electricity market, where a significant share (40–60%) can be purchased from the main grid; in this respect, the architecture provides a balanced solution between business as usual—full dependence on the main grid, providing energy supply only when local resources are insufficient on a long-term basis or when the energy price is low due to external factors, and the opposite tendency of full defection—which may require expensive and high storage needs.

- ■

- paving the road to 100% renewables (already endorsed by California and Hawaii for 2045) or towards 100% CO2-free energy systems (endorsed by European Union for 2050), without jeopardising the stability of electricity systems;

- ■

- minimising the cyber-security threat arising from system-level control, because the end-level of UniRCon is only locally controllable.

2.3. Resilient Architecture for Advanced Prosumers

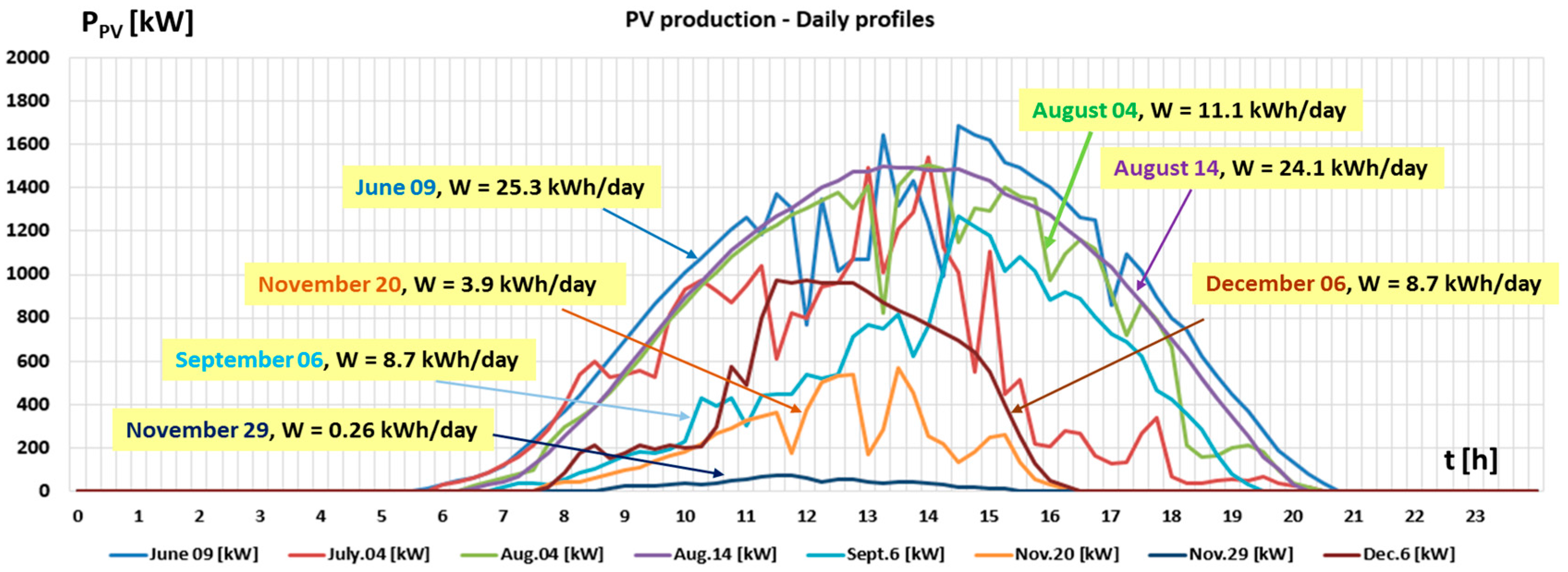

2.4. Numerical Simulation

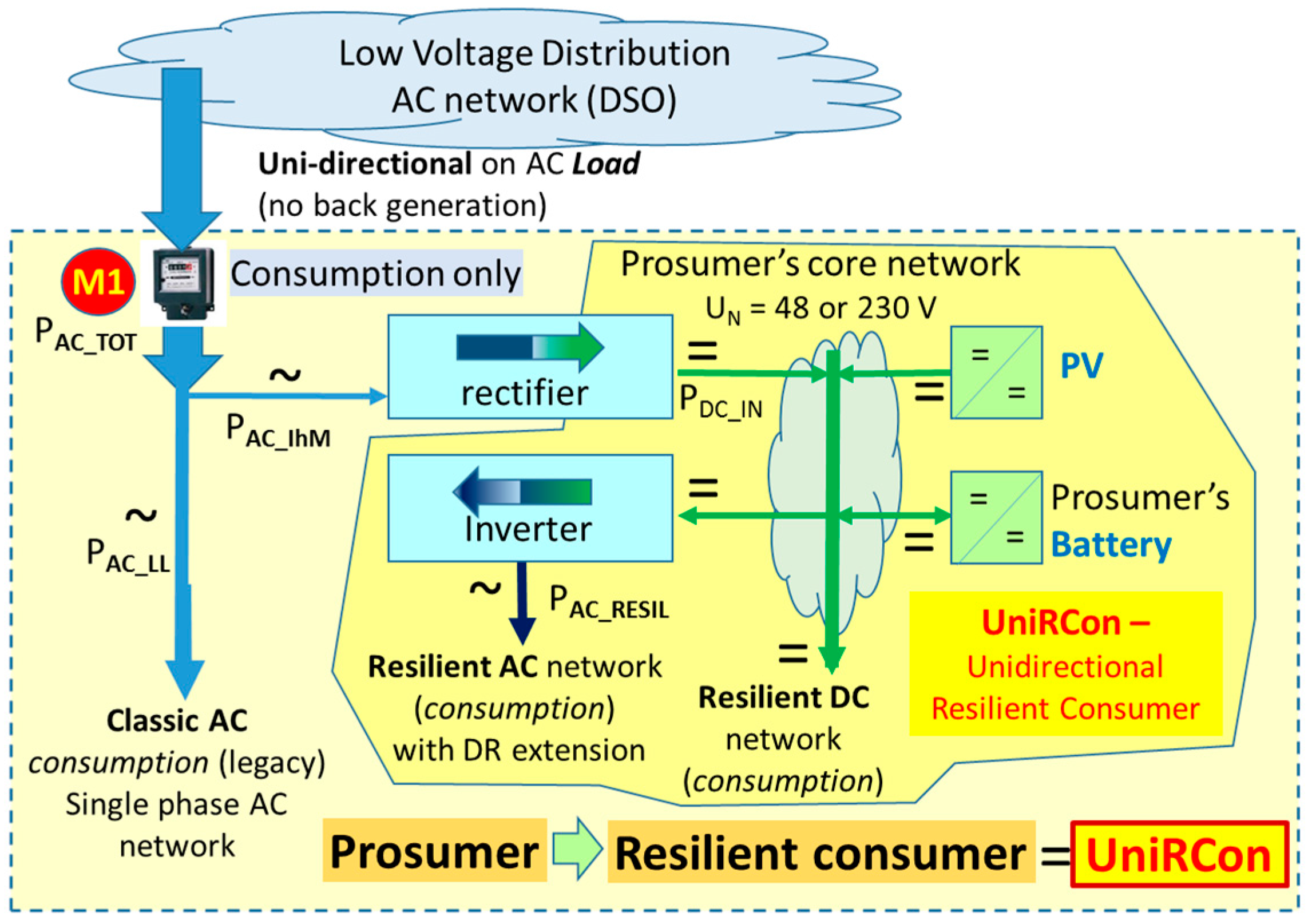

- The net power, , defined as 15-min average power, corresponds to the net meter M1; this is a classic net metering associated with FiT schemes; the net metering performed by M1 indicates total energy transferred from the grid to the end-user;

- The net power, is defined similarly and measured with the same net meter, however with the constraint that it describes uniquely the energy exchange between the grid and the end user, i.e., seen always as a load from the grid side. The excess power produced by the PV during the day is managed by the UniRCon architecture, able to control energy transfer to and from the battery or deploying demand-response algorithms.

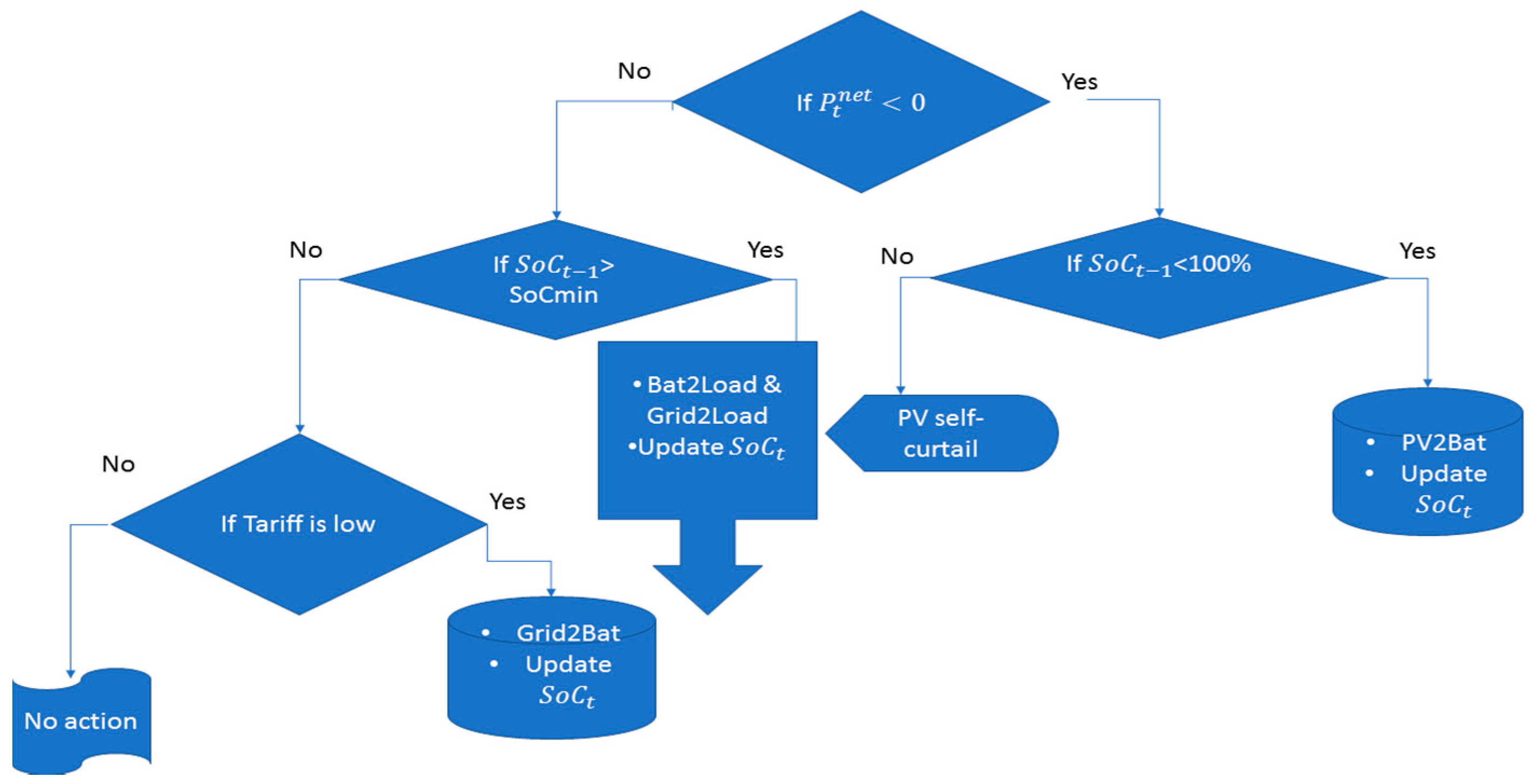

- A bottom-up approach is used, with a decision-logic subroutine for the daily scheduling of the battery (time of charge and discharge and amount of energy to be charged/discharged). This scheduling module is based on estimated average from past recorded data for PV and load demand. Thus, it is implemented as a deterministic model with perfect knowledge information. Note, however, that this approach does not affect the economic/technical calculations below. They indeed may influence a real-time operation of the system. The decision logic used for scheduling the battery is give in Figure 7.

- For the simplicity of calculations, we have limited the number of daily cycles of the battery to 1, where the cycle is counted as a full charge and discharge. This approach helps to relate all cost calculations to a daily-basis approach. Note that partial charges and discharges are allowed within the day if their cumulative effect does not exceed a full cycle. This constraint is reflected in the fixed cost associated with the aging effect on the battery due to its utilization. It is estimated as a specified ratio for each kWh of stored energy, as it is defined in Equation (11) from Table 3 below. This cost may also reflect the operation or wear-out cost of a battery due to operation. Calendar aging of the battery was ignored. We differentiate the types of storage technologies according to the number of guaranteed cycles (full charge and discharge).

- The inverter efficiency is considered in the proposed methodology by averaging the operation points and is taken as a constant for the rest of the calculations (European efficiency was used). The efficiency curve of an inverter is a highly non-linear curve with respect to their operation point. There is a lot of research underway where such curves are estimated and taken into account in the daily scheduling of a PV-battery system. Modelling the efficiency in such a form is, however, beyond the scope of this study, which looks at a long-term investment perspective rather than a daily scheduling method.

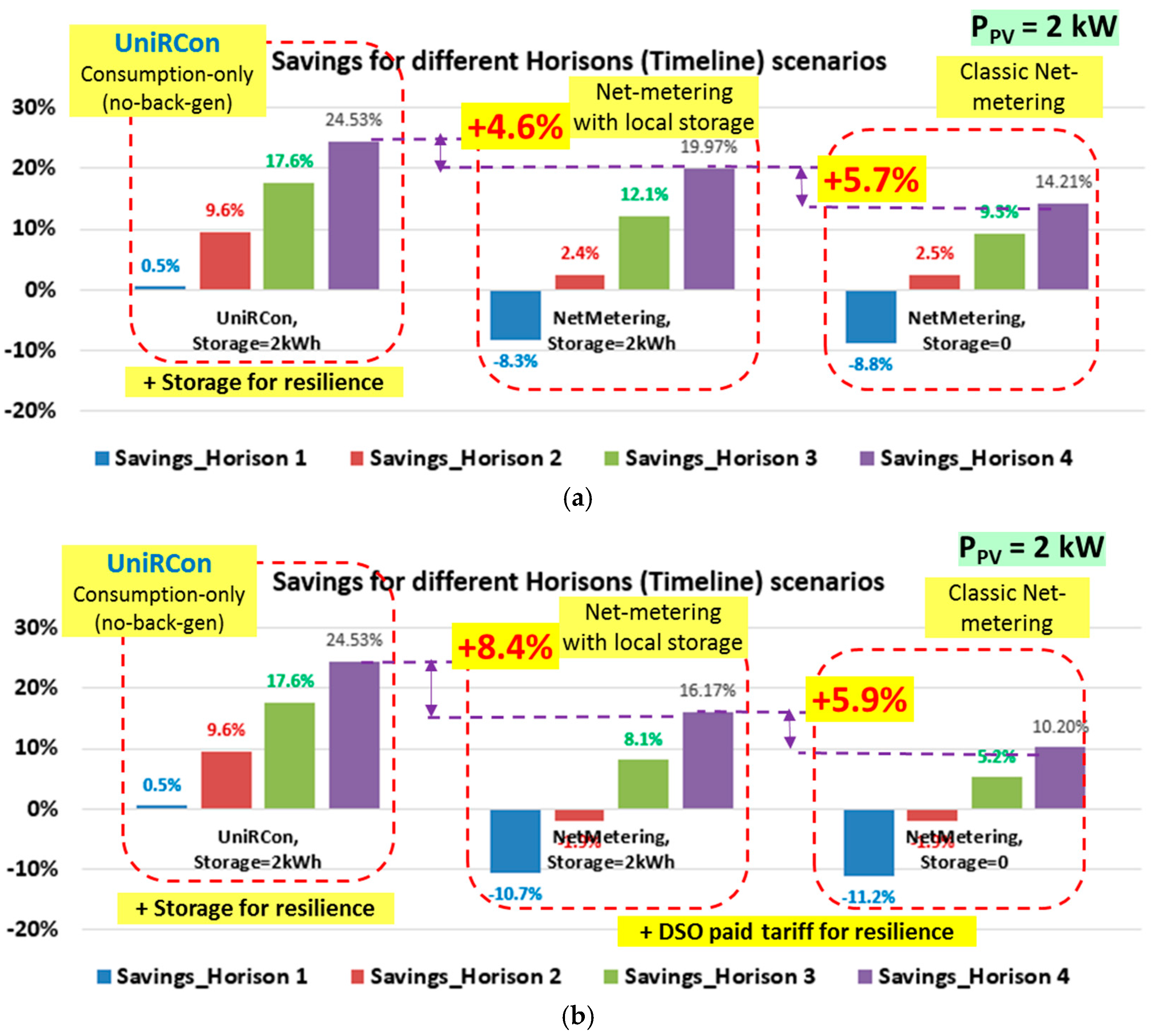

- (1)

- The use-case labelled UC1-NM considers the net-metering operation in the existing way, with PV installations behind the meter and no storage on the prosumer’s grid side;

- (2)

- The use-case labelled UC2-NM+Stor deals with the same case of a net-metering operation, with PV behind the meter but additionally 2 kWh of energy storage in the prosumer installations (behind the meter), in order to enable local use of the PV-produced energy;

- (3)

- The use-case labelled UC3-UniRCon corresponds to a so-called no back-generation situation, where the prosumer has only consumption on the grid side, but uses PV production and internal storage to enable local energy use together with a resilience feature; the use-case considers 2 kWh of local energy storage, in order to compare with the second use-case (3 kWh and 4 kWh of storage have also been analysed, but they are relevant in future work).

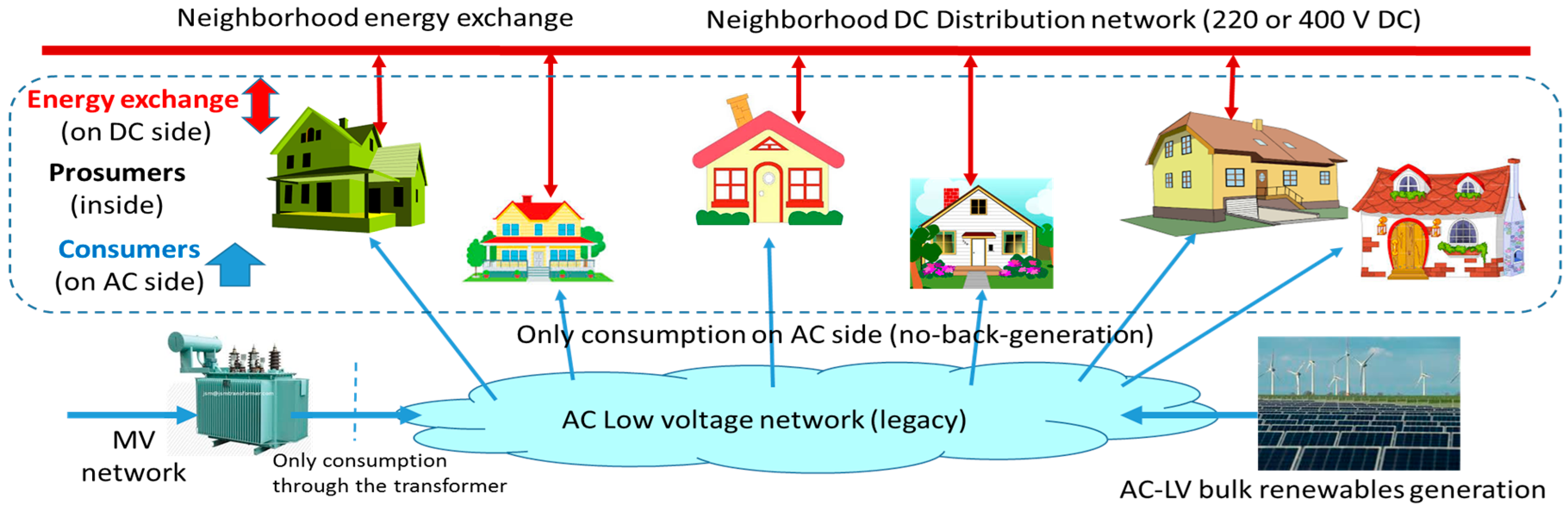

3. Expanding the Architecture towards Community-Level Energy Exchange

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lott, M.C.; Kim, S.-I.; Tam, C.; Houssin, D.; Gagné, J.-F. Technology Roadmap EnergyStorage; Energy Technology Perspective; IEA: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- ENTSO-E Network Code on Requirements for Grid Connection Applicable to All Generators RfG), ENTSO-E: 17 May 2016. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2016_112_R_0001 (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Denholm, P.; O’Connell, M.; Brinkman, G.; Jorgenson, J. Overgeneration from Solar Energy in California. A Field Guide to the Duck Chart; NREL: Denver, CO, USA, 2015; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kies, A.; Schyska, B.U.; von Bremen, L. Curtailment in a highly renewable power system and its effect on capacity factors. Energies 2016, 9, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, R.; Paulos, B. Curtailment of renewable energy in California and beyond. Electr. J. 2015, 28, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kies, A.; Schyska, B.U.; von Bremen, L. The demand side management potential to balance a highly renewable European power system. Energies 2016, 9, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Best Practices on Renewable Energy Self-Consumption; Working Document; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EURELECTRIC. Prosumers—An Integral Part of the Power System and the Market; Eurelectric Paper; EURELECTRIC: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Consumer Organization. Building a Consumer-Centric Energy Union; Position Paper; European Consumer Organization: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bourazeri, A.; Pitt, J.; Almajano, P.; Rodriguez, I.; Lopez-Sanchez, M. Meet the meter: Visualising smartgrids using self-organising electronic institutions and serious games. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Sixth International Conference on Self-Adaptive and Self-Organizing Systems Workshops, Lyon, France, 10–14 September 2012; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayaka, A.D.; Potdar, V.M.; Dillon, T.S.; Hussain, O.K.; Chang, E. A methodology to find influential prosumers in prosumer community groups. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2014, 10, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayaka, A.J.D.; Potdar, V.M.; Dillon, T.; Hussain, O.; Kuruppu, S. Goal-oriented prosumer community groups for the smart grid. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2014, 33, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Zhang, X.; Shahidehpour, M.; Alabdulwahab, A.; Abusorrah, A. Optimal interconnection planning of community microgrids with renewable energy sources. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubilla, K.; Jiménez-Estévez, G.A.; Hernádez, R.; Reyes-Chamorro, L.; Irigoyen, C.H.; Severino, B.; Palma-Behnke, R. Smart microgrids as a solution for rural electrification: Ensuring long-term sustainability through Cadastre and business models. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2014, 5, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottesen, S.Ø.; Tomasgard, A.; Fleten, S.-E. Prosumer bidding and scheduling in electricity markets. Energy 2016, 94, 828–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunescu, C.I.; Zabava, T.; Toma, L.; Bulac, C.; Eremia, M. Hardware home energy management system for monitoring the quality of energy service at small consumers. In Proceedings of the 2014 16th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), Bucharest, Romania, 25–28 May 2014; pp. 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, A.; Jacqmin, J.; Poudou, J.C. The prosumer and the grid. In Proceedings of the 65th Annual Meeting of the French Economic Association, Nancy, France, 27–29 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, H.C.; Martins, R.; Musilek, P.; Naumann, M.; Truong, C.N.; Jossen, A. Economic optimization of component sizing for residential battery storage systems. Energies 2017, 10, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Gooi, H.B.; Wang, M.Q. Sizing of energy storage for microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2012, 3, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, D. Pareto-efficient capacity planning for residential photovoltaic generation and energy storage with demand-side load management. Energies 2017, 10, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, A.M.; Severiano, C.A.; Karthik, S.; Kubis, M.; Zhao, L.; Martins, F.R.; Pereira, E.B.; Rüther, R.; Reindl, T. PV power conversion and short-term forecasting in a tropical, densely-built environment in Singapore. Renew. Energy 2016, 94, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zang, C.; Zeng, P.; Yu, H. Combined two-stage stochastic programming and receding horizon control strategy for microgrid energy management considering uncertainty. Energies 2016, 9, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, D.E.; Mehrizi-Sani, A.; Etemadi, A.H.; Cañizares, C.A.; Iravani, R.; Kazerani, M.; Hajimiragha, A.H.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O.; Saeedifard, M.; Palma-Behnke, R.; et al. Trends in microgrid control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1905–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschae, R.; Kato, T.; Matsuyama, T. Energy management in prosumer communities: A coordinated approach. Energies 2016, 9, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Liu, N.; Zhang, J.; Lei, J. Multi-objective optimal sizing for battery storage of PV-based microgrid with demand response. Energies 2016, 9, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, N.S.; Taylor, P.C.; Lang, P.D.; Jones, P.R. Evaluating the benefits of an electrical energy storage system in a future smart grid. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7180–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christoforidis, C.G.; Panapakidis, P.I.; Papadopoulos, A.T.; Papagiannis, K.G.; Koumparou, I.; Hadjipanayi, M.; Georghiou, E.G. A model for the assessment of different net-metering policies. Energies 2016, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, S.; Zafar, R.; Khan, A.N.; Butt, R.A.; Mahmood, A. A novel prosumer-based energy sharing and management (PESM) approach for cooperative demand side management (DSM) in smart grid. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, A.; Aiello, M. A novel strategy for optimising decentralised energy exchange for prosumers. Energies 2016, 9, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, N.C.; Naumann, M.; Karl, C.R.; Müller, M.; Jossen, A.; Hesse, C.H. Economics of residential photovoltaic battery systems in Germany: The case of Tesla’s Powerwall. Batteries 2016, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weniger, J.; Tjaden, T.; Quaschning, V. Sizing of residential PV battery systems. Energy Procedia 2014, 46, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFFEKTA Regeltechnik GmbH AX-Series, Hybrid, Solar Inverter, PV Inverter, UPS. Available online: http://www.effekta.com.de/AX-Series (accessed on 14 August 2017).

- California Public Utilities Commission. Bosch DC Microgrid Project; California Public Utilities Commission: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015.

- Sistem Fotovoltaic off Grid/Cu Stocare—Alaska Fotovoltaice (in Romanian). Available online: http://www.alaska-energies.ro/sisteme-fotovoltaice-rezidential/sistem-fotovoltaic-off-grid/ (accessed on 1 March 2017).

| Regulatory Aspects | Economic Evaluation of Photovoltaic–Battery Energy Storage (PV–BESS) Systems | Single Microgrid (MG) Approach | Community of MGs and/or Energy-Hubs |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2,3,4,5,7,8,9,26] | [13,18,19,20,27,28] | [23,24] | [11,12,13,14,22,29] |

| (i) | is a sub-unitary factor | |

| (ii) | is the total energy produced by the PV installation during the day, in (kWh) | |

| (iii) | is the total energy consumed during the day, in (kWh) |

| (1) | is the total energy needed during the day to supply the total aggregated loads, in (kWh); , is the average measured power consumption within the time step, in (kW); t is the time index used in the discretization of the time horizon into 15 min time-interval recordings; = is a ratio equivalent with 15 min recordings; T = 24 (h) is the time interval for a day in hours. | |

| (2) | is the total energy produced by the PV installation during the day, in (kWh). | |

| (3) | is the net-metering power balance (for each time interval ), in (kW). | |

| (4) | is the estimated value of daily energy that needs to be stored by the battery energy storage systems (BESS) in UniRCon architecture, in (kWh). | |

| (5) | is the energy sent back to the grid, (kWh); is the maximum allowable state of charge of the BESS, in (kWh). | |

| (6) | (kWh) | is the portion of PV power that is used locally (self-consumption), in (kWh); is the average efficiency of the inverter. |

| (7) | Energy coming from the DSO, in (kWh). | |

| (8) | Total daily cost of the energy if all loads are supplied with energy from the DSO, in (€); is the unit cost of energy purchased from the DSO, in (€/kWh). | |

| (9) | Total daily cost of the energy purchased from the DSO, in (€). | |

| (10) | is the estimated fixed daily cost for the PV system, in (€); (kW) is the installed PV capacity; is the fixed cost per unit of kWh of PV produced energy (€/kWh); is the total number of hours within a year (h/year); total number of simulated years (years). | |

| (11) | is the fixed daily cost for the BESS, in (€). is the battery-installed energy necessary for increasing PV self-consumption, in (kWh); is the installed energy required for resilience, in (kWh); is the fixed cost per unit of kWh of battery storage, in (€/kWh); total number of guaranteed cycles for the respective BESS technology, in (p.u.). | |

| (12) | are opportunity savings when using the battery to buy energy from the grid when it is cheap and use it when it is expensive, in (€); amount of energy purchased at low prices from DSO and stored in the battery for later use, in (kWh); difference in tariffs (e.g., day-night or real-market prices), in (€/kWh); coefficient capturing the market opening for opportunities (p.u). | |

| (13) | = | are the savings for sold energy, in (€); curtailment factor for PV excess energy (not accepted into the grid), in (p.u.); is the price at which the energy coming from PV is sold to the grid (it is assumed different than the price of purchasing energy from the grid), in (€/kWh). |

| (14) | + | is the total cost of prosumer-used energy, in (€); are the cost for the lost energy due to charge/discharge cycles and other aging factors for the BESS, in (€); is the daily ratio of the cost needed for communication with TSO/DSO, in (€). |

| (15) | is the period, expressed in minutes, based on the supplementary energy in a battery, kept only for resilience situations. | |

| (16) | are the relative savings in the UniRcon architecture, in (%) from the total cost if all energy would be purchased from the grid. |

| Abbreviation | Description | H 1 | H 2 | H 3 | H 4 | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of battery investment | 700 | 600 | 500 | 400 | €/kWh | |

| Number of battery cycles per lifetime | 7000 | 7000 | 7000 | 7000 | Cycles | |

| Specific cost of the service to store energy in BESS—storage as a service SaaS | 0.100 | 0.080 | 0.063 | 0.044 | €/kWh | |

| Electricity tariff (flat) for purchasing the energy from the grid | 0.120 | 0.130 | 0.140 | 0.150 | €/kWh | |

| Minimum tariff used for the energy supplied to the loads | 0.060 | 0.065 | 0.070 | 0.075 | €/kWh | |

| KM | The market opportunity factor for buying cheap(er) energy | 20% | 40% | 60% | 80% | [%] |

| Tariff used to buy back the injected energy into the distribution network FiT | 0.080 | 0.060 | 0.040 | 0.020 | €/kWh | |

| Overall efficiency of the batteries | 90% | 91% | 93% | 95% | [%] | |

| Curtailment factor for PV excess energy to be sent into the grid | 0.00% | 10.00% | 15% | 25.00% | [%] | |

| Cost of PV for each installed kW, UniRCon solution | 1500 | 1200 | 900 | 600 | €/kW | |

| Cost/kW_PV (includes the cost of power electronics and installation) | 1800 | 1400 | 1100 | 800 | €/kWh | |

| Number of hours per year (at PV nominal power) | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | hour/year | |

| Number of years for PV and Electric Power investment return | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | Years | |

| Cost of kWh produced, PV with UniRCon | 0.083 | 0.06 | 0.050 | 0.0325 | €/kWh | |

| Cost of kWh produced, PV classic | 0.100 | 0.078 | 0.061 | 0.044 | €/kWh produced | |

| Battery energy used only for resilience | 0.060 | 0.165 | 0.220 | 0.325 | kWh | |

| ResilienceAC_Genxit | Resilience [min] with UniRCon, based on EBAT_RESIL | 4 | 12 | 16 | 24 | min |

| ResilienceDay_UniRCon | Resilience, [%] per day with UniRCon | 0.3% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 1.7% | [%] |

| Efficiency of PV-BESS in classic option 1 | 86.0% | 87.0% | 88.0% | 89.0% | [%] | |

| Efficiency of PV-BESS for the UniRCon | 91.0% | 92.0% | 93% | 94.0% | [%] | |

| Year | Scenarios run for the respective year | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | 2025 | Year |

| C_RESIL_Day | DSO daily tariff (cost) for resilience provision | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | €/day |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanduleac, M.; Ciornei, I.; Albu, M.; Toma, L.; Sturzeanu, M.; Martins, J.F. Resilient Prosumer Scenario in a Changing Regulatory Environment—The UniRCon Solution. Energies 2017, 10, 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10121941

Sanduleac M, Ciornei I, Albu M, Toma L, Sturzeanu M, Martins JF. Resilient Prosumer Scenario in a Changing Regulatory Environment—The UniRCon Solution. Energies. 2017; 10(12):1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10121941

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanduleac, Mihai, Irina Ciornei, Mihaela Albu, Lucian Toma, Marta Sturzeanu, and João F. Martins. 2017. "Resilient Prosumer Scenario in a Changing Regulatory Environment—The UniRCon Solution" Energies 10, no. 12: 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10121941

APA StyleSanduleac, M., Ciornei, I., Albu, M., Toma, L., Sturzeanu, M., & Martins, J. F. (2017). Resilient Prosumer Scenario in a Changing Regulatory Environment—The UniRCon Solution. Energies, 10(12), 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10121941