Novel Aluminum Oxide-Impregnated Carbon Nanotube Membrane for the Removal of Cadmium from Aqueous Solution

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

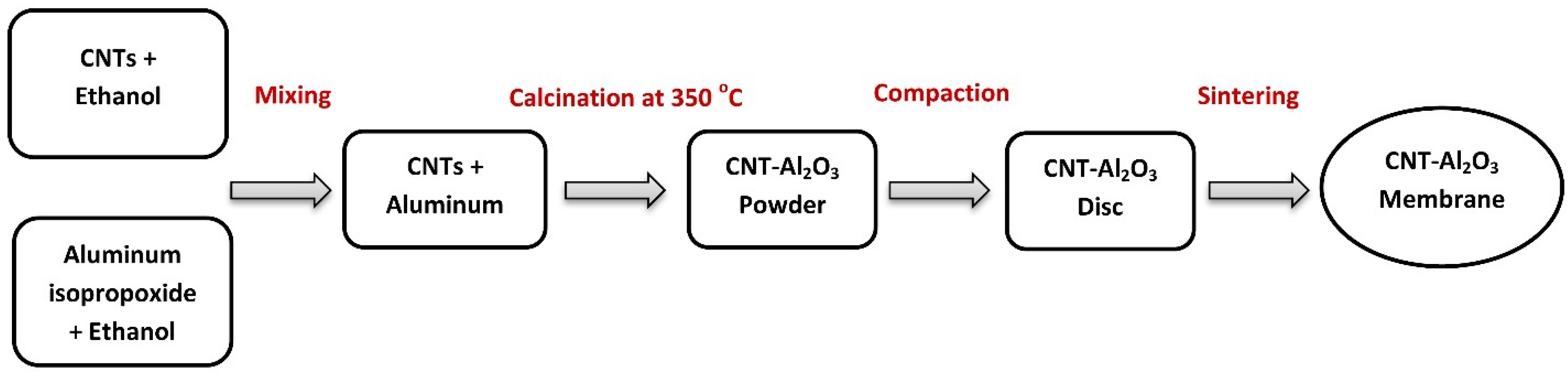

2.2. Impregnated Aluminum Oxide-Carbon Nanotubes

2.3. Membrane Preparation

2.4. Characterization Analysis of Raw and Impregnated CNTs and Membranes

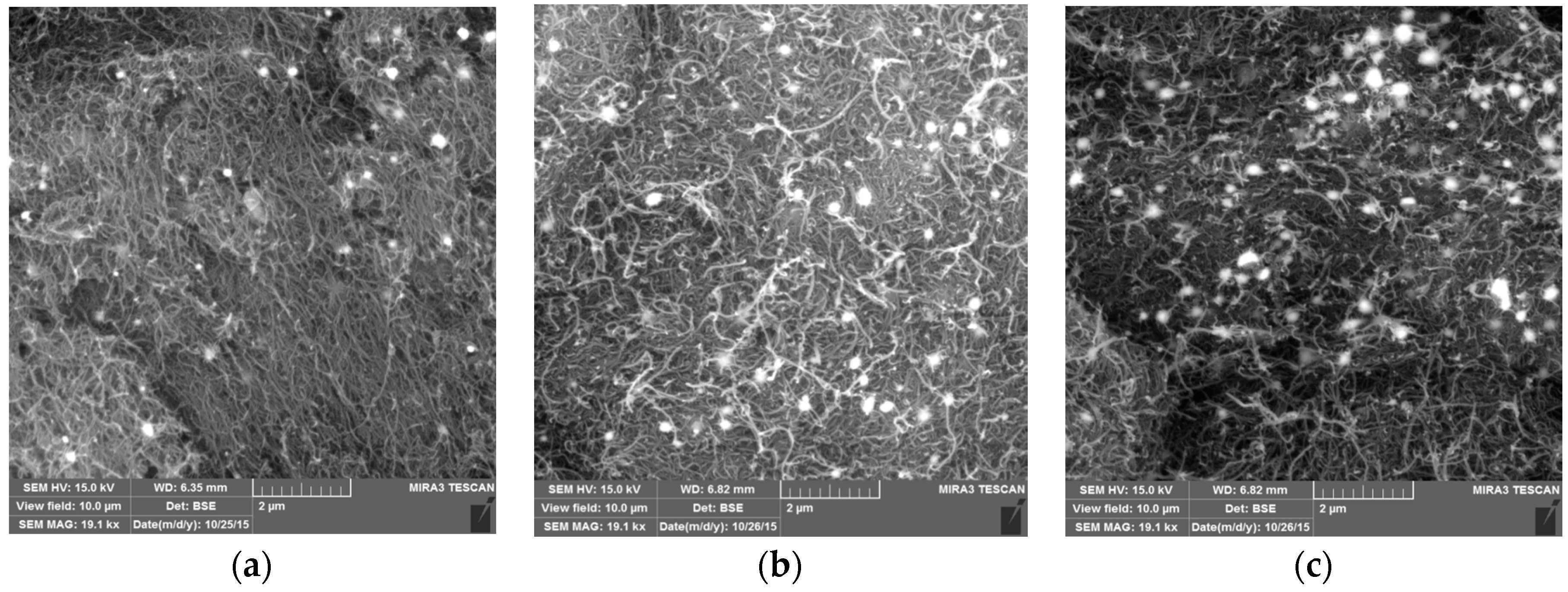

2.4.1. SEM Analysis

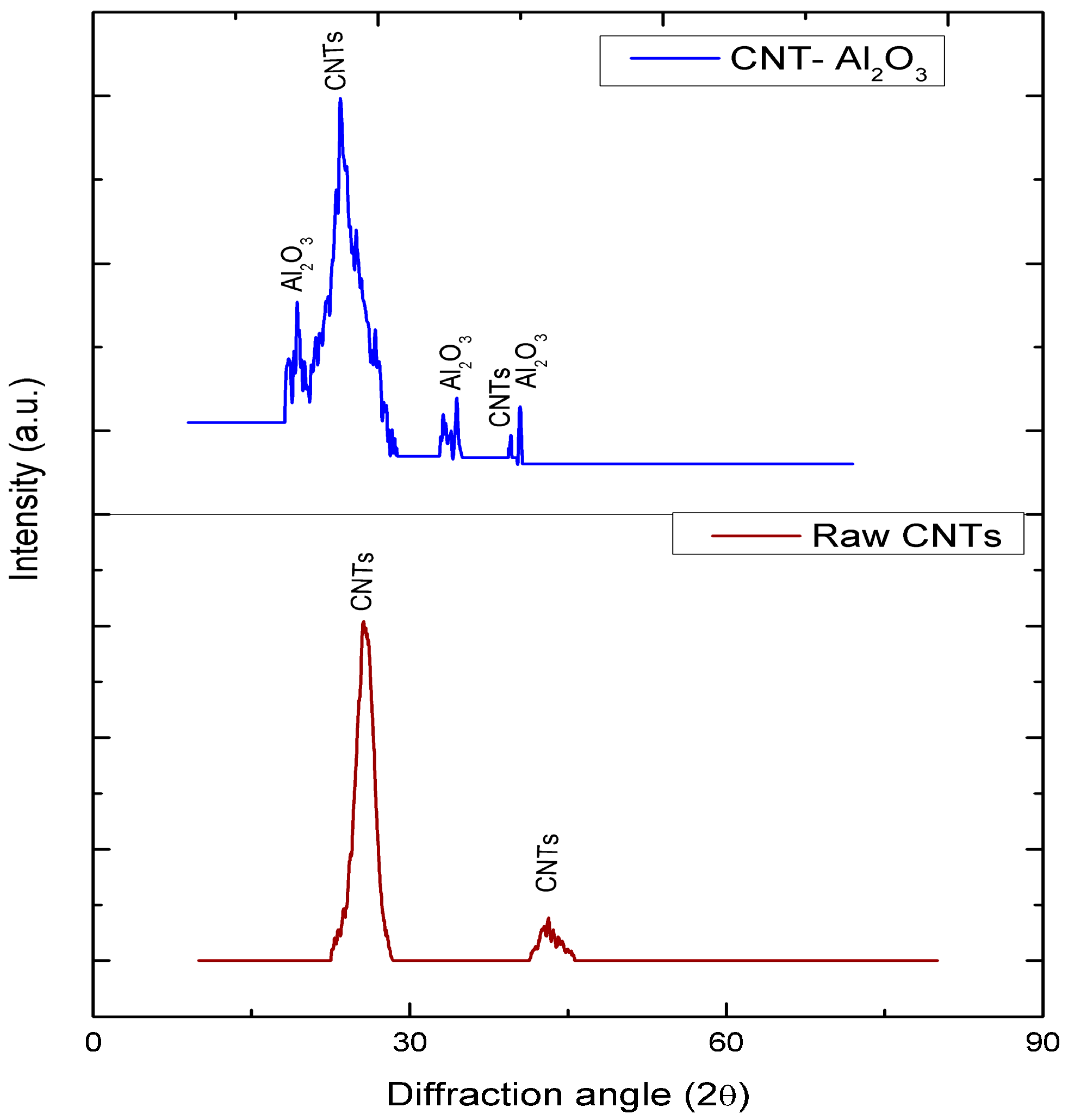

2.4.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.4.3. Porosity Measurement

2.4.4. Contact Angle Measurement

2.4.5. Zeta Potential Measurement

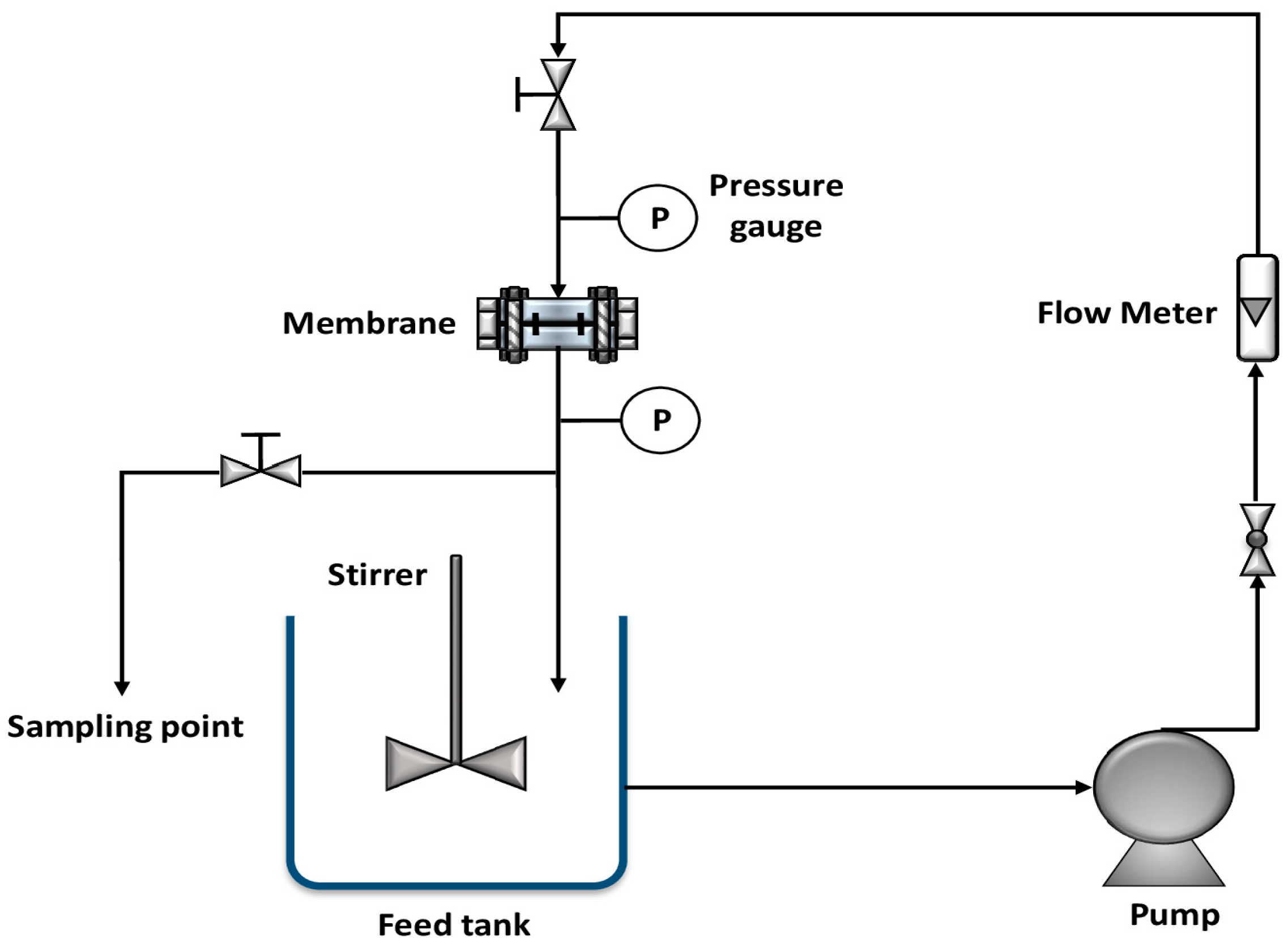

2.5. Continuous Filtration System

2.6. Analytical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SEM and EDS Analysis

3.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

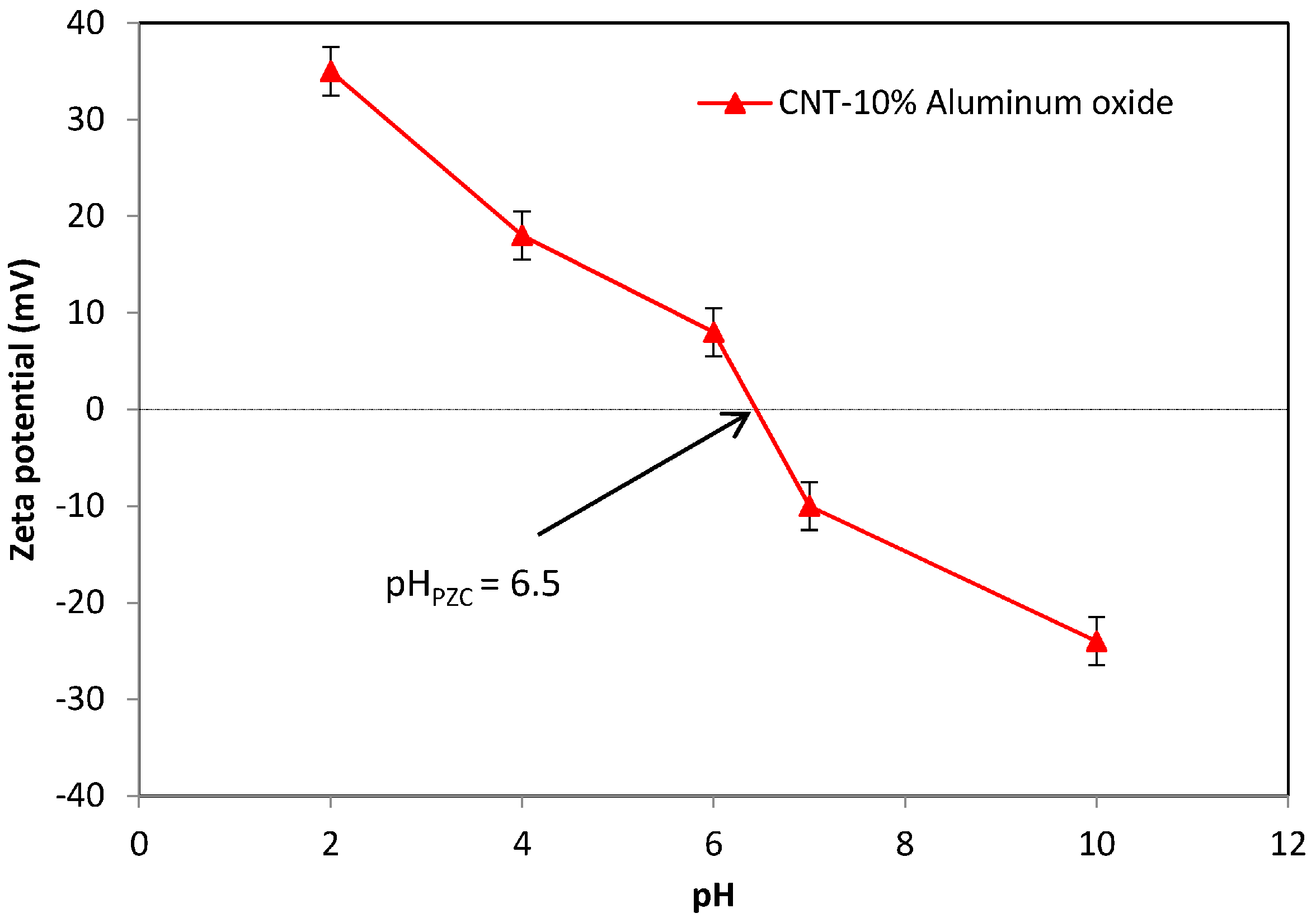

3.3. Measurement of the Zeta Potential and Point of Zero Electric Charge (pHPZC)

3.4. Membrane Characterization

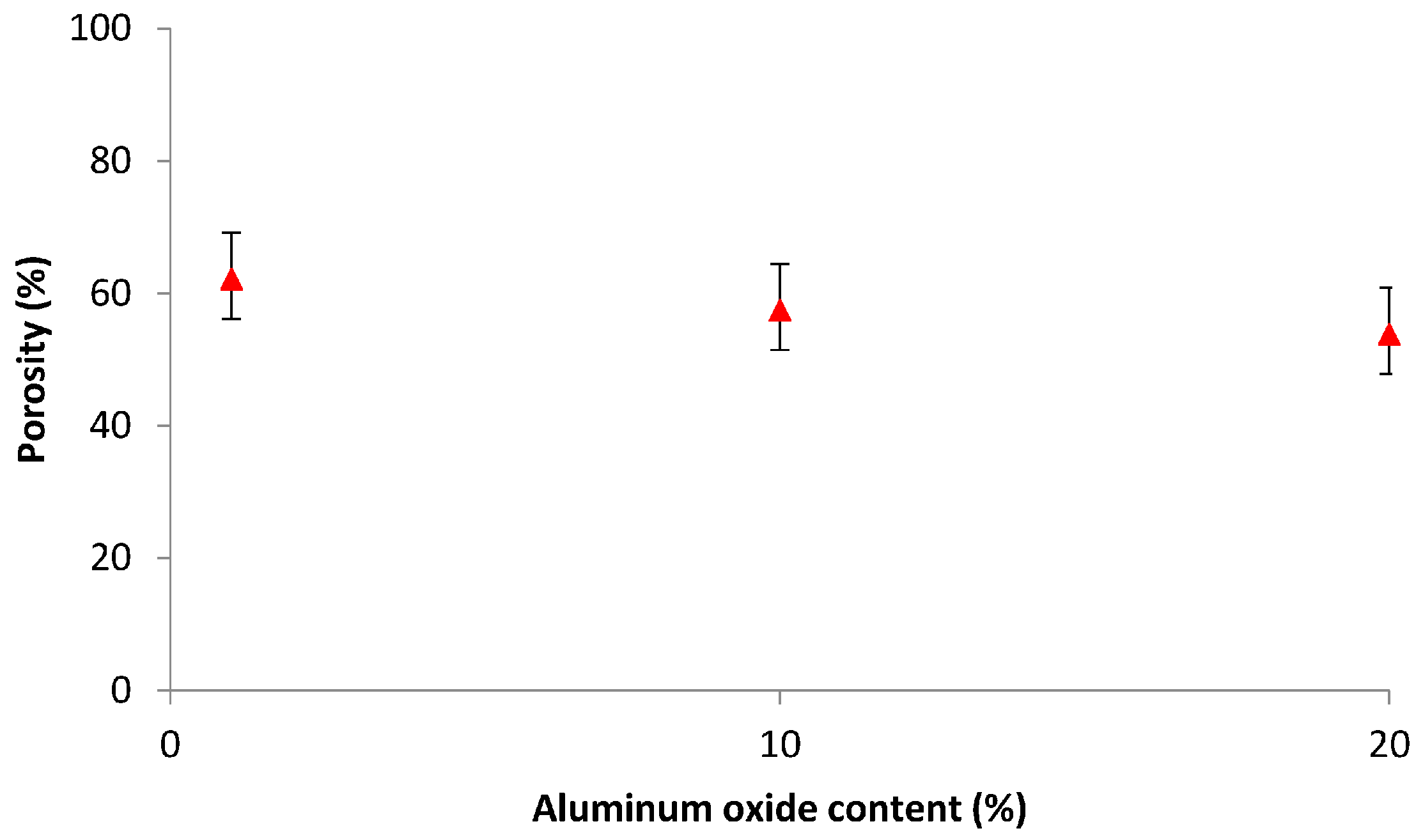

3.4.1. Porosity Measurement

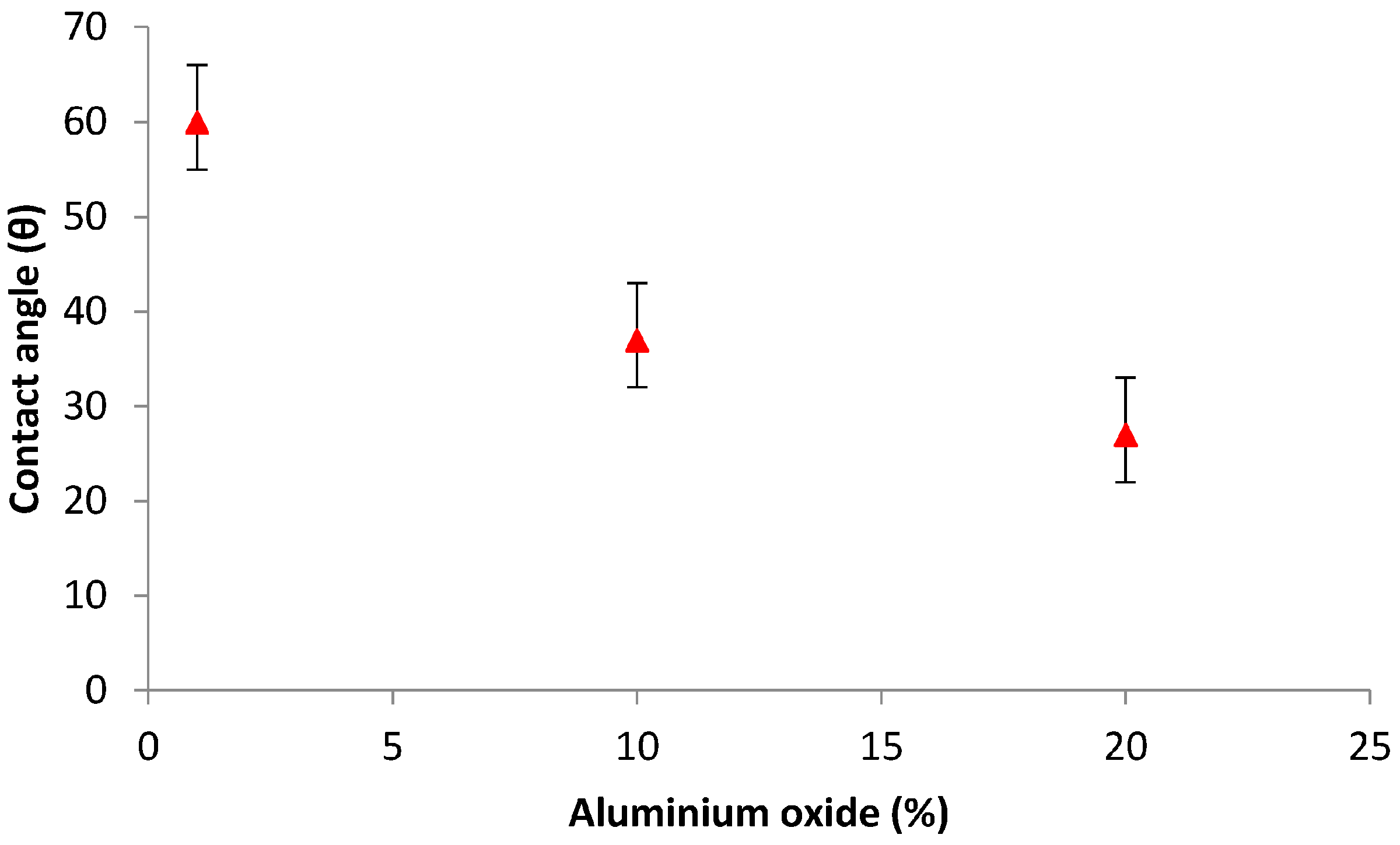

3.4.2. Contact Angle Measurement

3.5. Water Flux Measurements: Effect of Transmembrane Pressure Difference and Aluminum Oxide Loading

3.6. Cadmium Removal

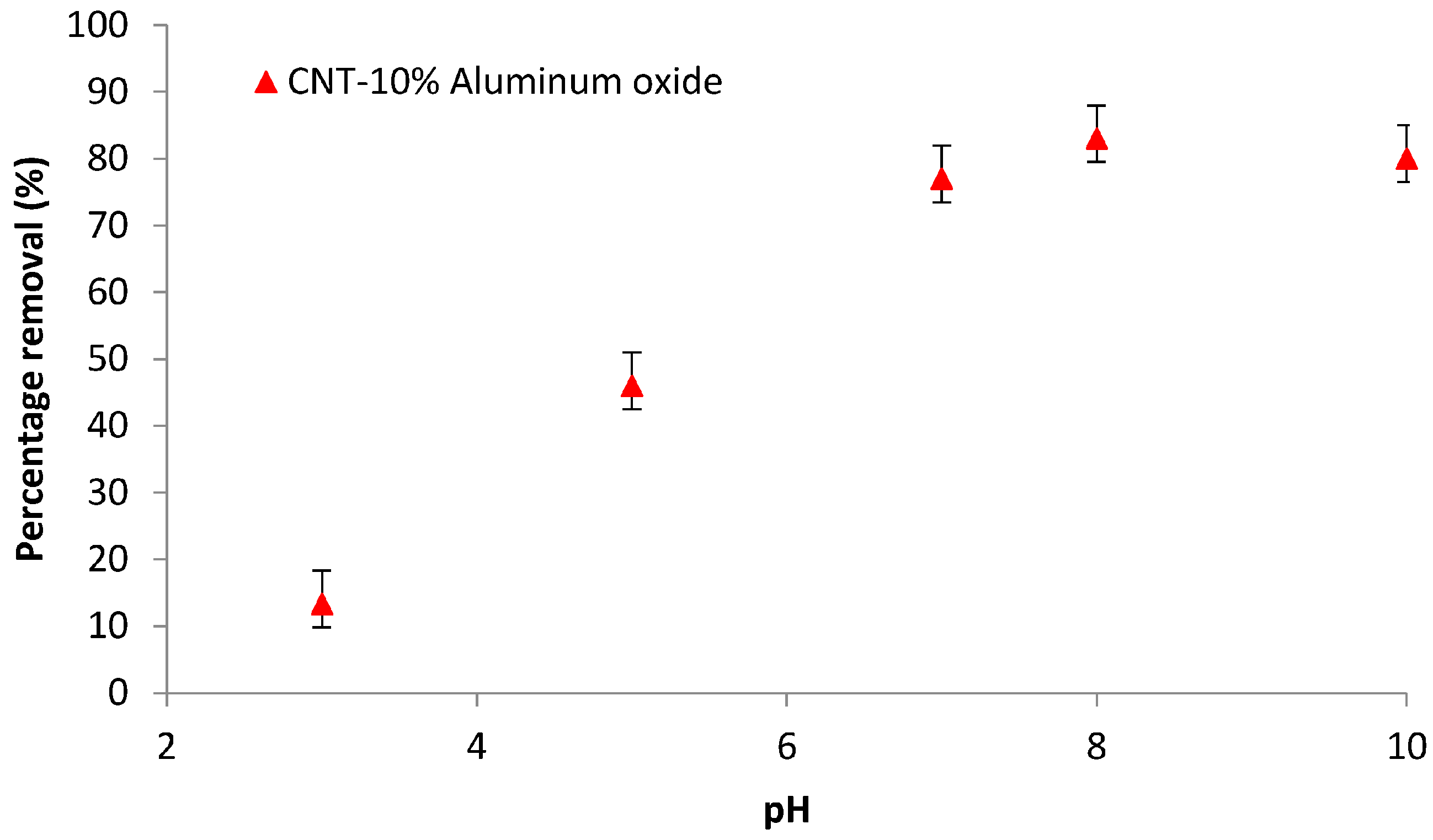

3.6.1. Effect of Feed pH

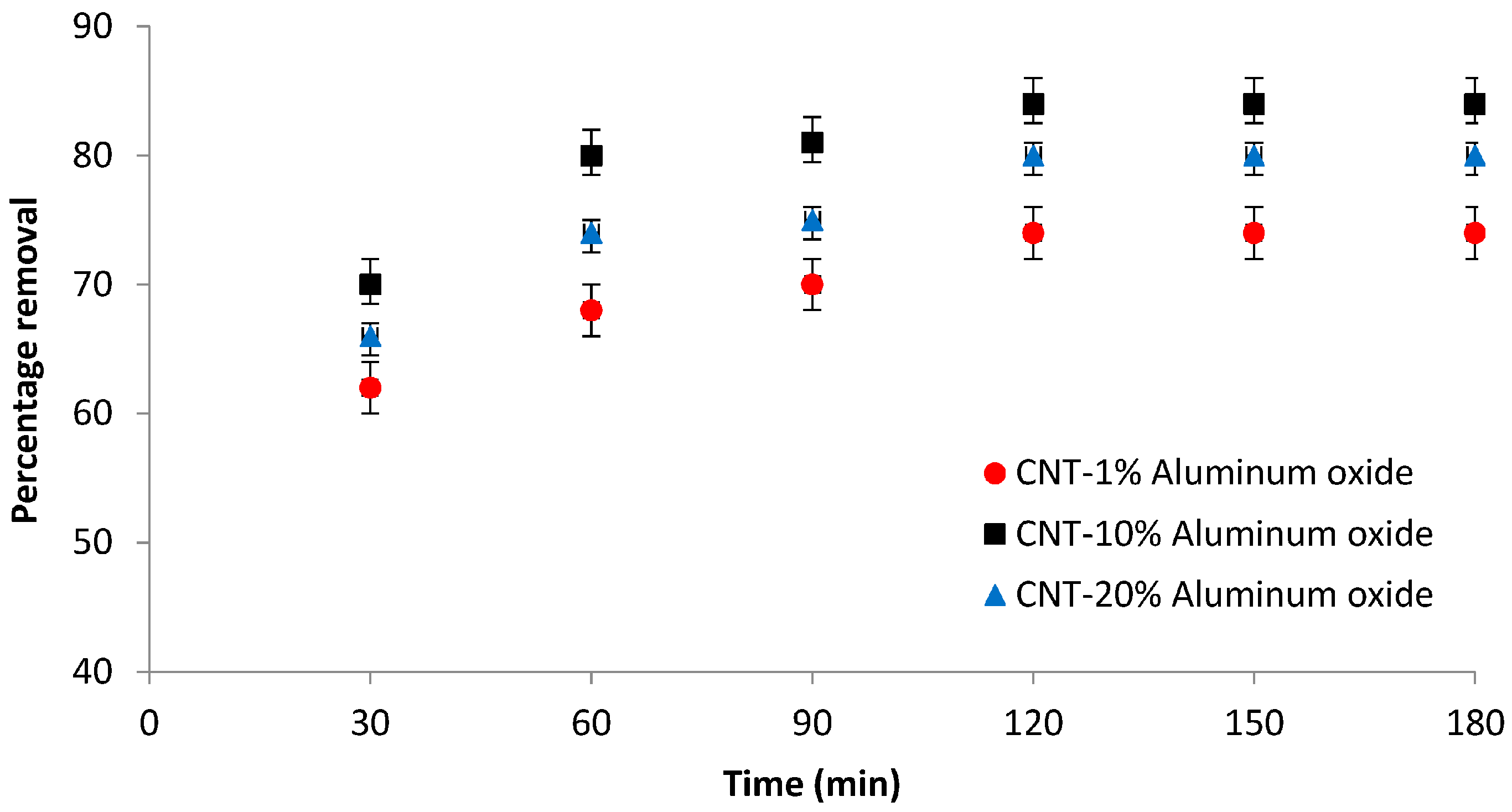

3.6.2. Effect of Time

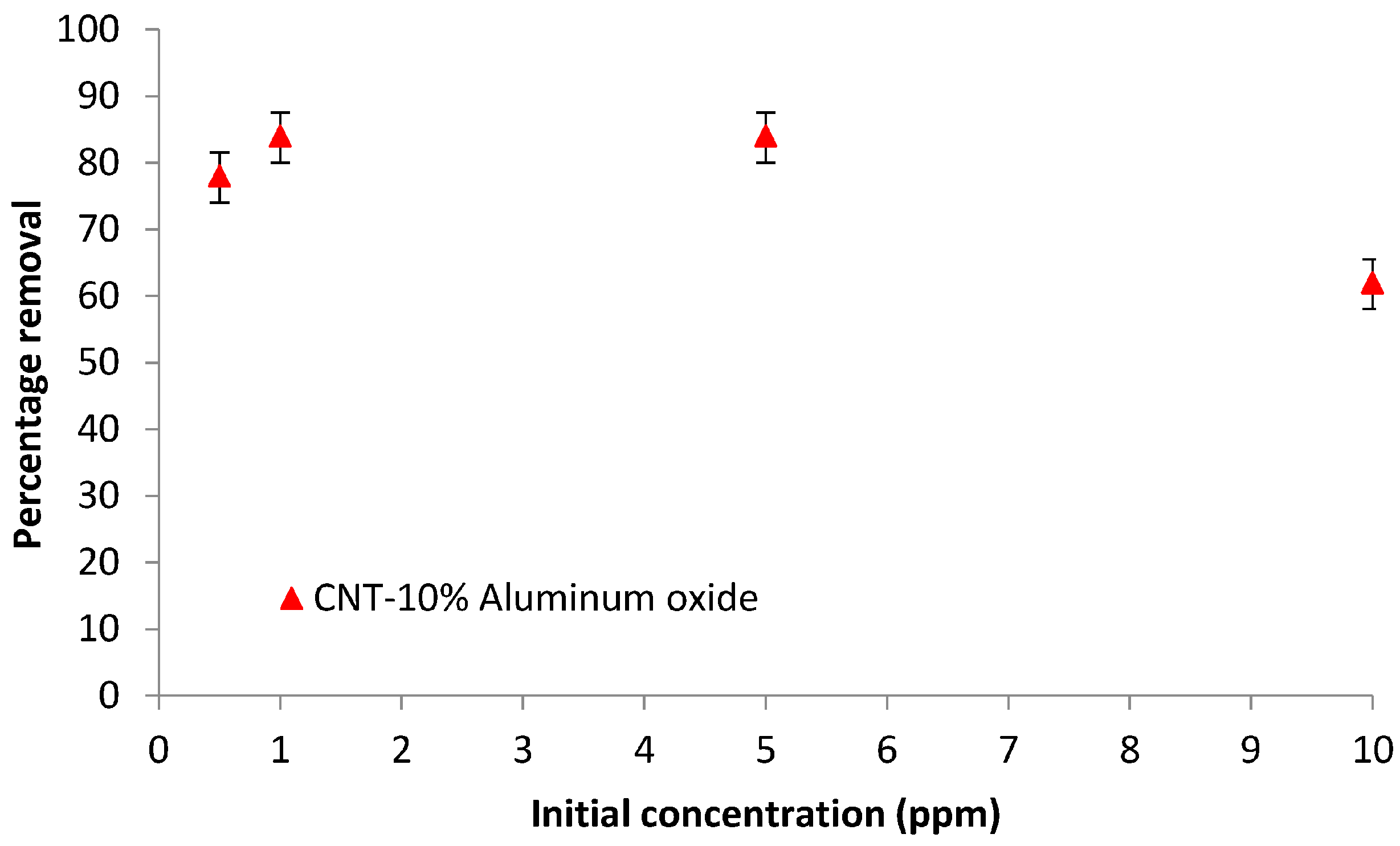

3.6.3. Effect of the Initial Concentration

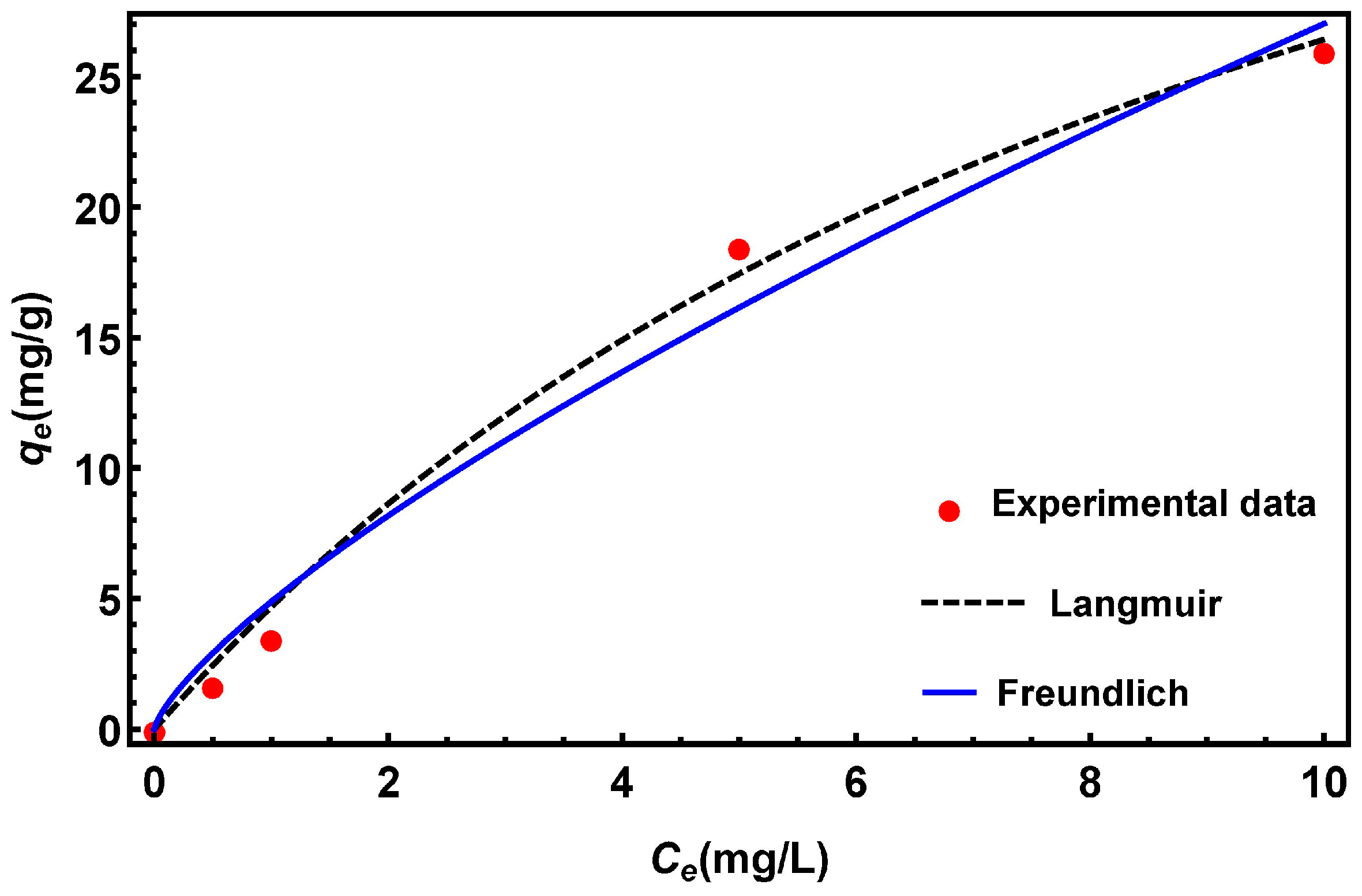

3.6.4. Adsorption Isotherms

3.7. Mechanism of Cadmium Ion Removal by the CNT-10% Al2O3 Membrane

3.8. Comparative Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. International Standards for Drinking Water; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Luan, Z.; Ding, J.; Xu, C. Adsorption of cadmium(II) from aqueous solution by surface oxidized carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2003, 41, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsanullah; Al-Khaldi, F.A.; Abusharkh, B.; Khaled, M.; Atieh, M.A.; Nasser, M.S.; Laoui, T.; Saleh, T.A.; Agarwal, S.; Tyagi, I.; et al. Adsorptive removal of cadmium(II) ions from liquid phase using acid modified carbon-based adsorbents. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 204, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, J.W. Adsorption of cadmium(II) ions from aqueous solution by a new low-cost adsorbent—Bamboo charcoal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wu, S.; Liu, G.; Liao, X.; Deng, X.; Sun, D.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y. Simultaneous biosorption of cadmium(II) and lead(II) ions by pretreated biomass of phanerochaete chrysosporium. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2004, 34, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsanullah; Abbas, A.; Al-Amer, A.M.; Laoui, T.; Al-Marri, M.J.; Nasser, M.S.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M.A. Heavy metal removal from aqueous solution by advanced carbon nanotubes: Critical review of adsorption applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 157, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmaly, H.A.; Abussaud, B.; Ihsanullah; Saleh, T.A.; Gupta, V.K.; Atieh, M.A. Ferric oxide nanoparticles decorated carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers: From synthesis to enhanced removal of phenol. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2015, 19, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmaly, H.A.; Abussaud, B.; Ihsanullah; Saleh, T.A.; Bukhari, A.A.; Laoui, T.; Shemsi, A.M.; Gupta, V.K.; Atieh, M.A. Evaluation of micro- and nano-carbon-based adsorbents for the removal of phenol from aqueous solutions. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2015, 97, 1164–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Abussaud, B.A.; Al-baghli, N.A.H.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M.A. Benzene removal by iron oxide nanoparticles decorated carbon nanotubes. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 5654129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Abussaud, B.A.; Ihsanullah; Al-baghli, N.A.H.; Redhwi, H.H. Adsorption of Toluene and Paraxylene from aqueous solution using pure and iron oxide impregnated carbon nanotubes: Kinetics and isotherms study. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2017, 2017, 2853925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.C.; Teow, Y.H.; Ang, W.L.; Mohammad, A.W. Novel GO/OMWCNTs mixed-matrix membrane with enhanced antifouling property for palm oil mill effluent treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 177, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liao, G.; Liu, Z.; Pan, Y.; Wu, Q.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Tsui, O.K.C. Enhanced water flux in vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays and polyethersulfone composite membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 12171–12176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.; Chopra, N.; Andrews, R.; Hinds, B.J. Nanoscale hydrodynamics: Enhanced flow in carbon nanotubes. Nature 2005, 438, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, J.K.; Park, H.G.; Wang, Y.; Stadermann, M.; Artyukhin, A.B.; Grigoropoulos, C.P.; Noy, A.; Bakajin, O. Fast mass transport through sub-2-nanometer carbon nanotubes. Science 2006, 312, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Srivastava, O.N.; Talapatra, S.; Vajtai, R.; Ajayan, P.M. Carbon nanotube filters. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, S.; Fierro, D.; Buhr, K.; Wind, J.; Du, B.; Boschetti-de-Fierro, A.; Abetz, V. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) mixed polyacrylonitrile (PAN) ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 403–404, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, A.K.S.; Dwivedi, V.; Dasgupta, K.; Ali, S.M.; Shenoy, K.T. Novel amidoamine functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes for removal of mercury(II) ions from wastewater: Combined Experimental and density functional theoretical approach. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 899–911. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Ye, Y.; Ward, A.J.; Zhou, C.; Chen, V.; Andrew, I.; Lee, S.; Liu, Z.; Chae, S.; Shi, J. High flux and high selectivity carbon nanotube composite membrane for natural organic matter removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 163, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabi, H.; Ehsan, M.; Vatanpour, V.; Shockravi, A.; Safarpour, M. Improvement in desalination performance of thin film nanocomposite nano filtration membrane using amine-functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotube. Desalination 2016, 394, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, B.J.; Chopra, N.; Rantell, T.; Andrews, R.; Gavalas, V.; Bachas, L.G. Aligned multiwalled carbon nanotube membranes. Science 2004, 303, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, R.; Jacques, D.; Rao, A.M.; Derbyshire, F.; Qian, D.; Fan, X.; Dickey, E.C.; Chen, J. Continuous production of aligned carbon nanotubes: A step closer to commercial realization. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 303, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, G.T.; Park, Y.-B.; Wang, S.; Liang, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Funchess, P.; Kramer, L. Mechanical and electrical properties of polycarbonate nanotube buckypaper composite sheets. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 325705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumée, L.F.; Sears, K.; Schütz, J.; Finn, N.; Huynh, C.; Hawkins, S.; Duke, M.; Gray, S. Characterization and evaluation of carbon nanotube Bucky-Paper membranes for direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 351, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooper, S.M.; Chuang, H.F.; Cinke, M.; Cruden, B.A.; Meyyappan, M. Gas permeability of a buckypaper membrane. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, M.; Pan, S.; Li, H. Well-aligned carbon nanotube array membrane synthesized in porous alumina template by chemical vapor deposition. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2000, 45, 1373–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofighy, M.A.; Shirazi, Y.; Mohammadi, T.; Pak, A. Salty water desalination using carbon nanotubes membrane. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 168, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, J.; Yuan, X.; Dong, H.; Zeng, G.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Hua, S.; Zhang, S.; et al. Facile synthesis of alumina-decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes for simultaneous adsorption of cadmium ion and trichloroethylene. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 273, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsanullah; Al Amer, A.M.; Laoui, T.; Abbas, A.; Al-aqeeli, N.; Patel, F.; Khraisheh, M.; Ali, M.; Hilal, N. Fabrication and antifouling behaviour of a carbon nanotube membrane. Mater. Des. 2016, 89, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsanullah; Laoui, T.; Al-Amer, A.M.; Khalil, A.B.; Abbas, A.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M.A. Novel anti-microbial membrane for desalination pretreatment: A silver nanoparticle-doped carbon nanotube membrane. Desalination 2015, 376, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Fan, Z.; Luo, G.; Wei, G. A new structure for multi-walled carbon nanotubes reinforced alumina nanocomposite with high strength and toughness. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Yan, J.; Wei, T. Preparation of graphene nanosheet/alumina composites by spark plasma sintering. Mater. Res. Bull. 2011, 46, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Ramos, R.; Rangel-Mendez, J.R.; Mendoza-Barron, J.; Fuentes-Rubio, L.; Guerrero-Coronado, R.M. Adsorption of cadmium(II) from aqueous solution onto activated carbon. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 35, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, G.D.; Marinkovic, A.D.; Coli, M.; Risti, M.Ð.; Aleksić, R.; Perić-Grujić, A.A.; Uskoković, P.S. Removal of cadmium from aqueous solutions by oxidized and ethylenediamine-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 157, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozutsumi, K.; Takamuku, T.; Shin-ichi, I.; Ohtaki, H. An X-ray diffraction study on the structure of solvated cadmium(II) ion and tetrathiocyanatocadmate(II) complex in N,N-dimethylformamide. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1989, 62, 1875–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.K.; Kim, Y.M.; Woo, S.H.; Park, J.M. Removal of cadmium using acid-treated activated carbon in the presence of nonionic and/or anionic surfactants. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 99, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.K.; Park, D.; Woo, S.H.; Park, J.M. Removal of cationic heavy metal from aqueous solution by activated carbon impregnated with anionic surfactants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 164, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Bandosz, T.J.; Zhao, Z.; Han, M.; Qiu, J. Investigation of factors affecting adsorption of transition metals on oxidized carbon nanotubes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 167, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khaldi, F.A.; Abu-Sharkh, B.; Abulkibash, A.M.; Atieh, M.A. Cadmium removal by activated carbon, carbon nanotubes, carbon nanofibers, and carbon fly ash: A comparative study. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfa, O.M.; Yalçinkaya, Ö.; Türker, A.R. Synthesis and characterization of nano-scale alumina on single walled carbon nanotube. Inorg. Mater. 2009, 45, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, O. The removal of ions by functionalized carbon nanotube: Equilibrium, isotherms and thermodynamic studies. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2011, 25, 229–240. [Google Scholar]

| Experimental Set | Al2O3 Loading (wt %) in the Membrane | Transmembrane Pressure Difference (psi) | pH of the Solution | Initial Concentration of Cd(II) (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CNT-10% Al2O | 15 | 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 | 1 |

| 2 | CNT-1% Al2O3 | 15 | 7 | 0.5, 1, 5, 10 |

| 3 | CNT-10% Al2O3 | 15 | 7 | 0.5, 1, 5, 10 |

| 4 | CNT-20% Al2O3 | 15 | 7 | 0.5, 1, 5, 10 |

| Model | Parameters | CNT-10% Al2O3 Membrane |

|---|---|---|

| Langmuir () | KL (L/mg) | 0.09 |

| qm (mg/g) | 54.42 | |

| R2 | 0.997 | |

| Freundlich () | KF (mg/g)·(L/mg)1/n | 4.89 |

| N | 1.35 | |

| R2 | 0.99 |

| Adsorbent | Experimental Conditions | Percentage Removal | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-grown CNTs | pH 5.5, initial concentration = 4 mg/L | - | 1.1 | [2] |

| H2O2 oxidized CNTs | pH 5.5, initial concentration = 4 mg/L | - | 2.6 | [2] |

| HNO3 oxidized CNTs | pH 5.5, initial concentration = 4 mg/L | - | 5.1 | [2] |

| Acid-modified CNTs | pH 7, initial concentration = 1 ppm | 93 | 4.35 | [3] |

| Raw CNTs | pH 7, initial concentration = 1 ppm | 27 | 1.661 | [38] |

| Ethylenediamine-functionalized MWCNTs | pH 8, initial concentration = 5 mg/L | - | 25.70 | [33] |

| SWCNTs | pH 8 | - | 1.97 | [39] |

| Nano-alumina/SWCNTs | pH 8 | - | 2.18 | [39] |

| SWCNTs-COOH | pH 5, initial concentration = 20 mg/L | 69.97 | 55.89 | [40] |

| CNT-10% Al2O3 membrane | pH 7, initial concentration = 1 mg/L, contact time = 2 h | 84 | 54.42 | This study |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ihsanullah; Patel, F.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M.A.; Laoui, T. Novel Aluminum Oxide-Impregnated Carbon Nanotube Membrane for the Removal of Cadmium from Aqueous Solution. Materials 2017, 10, 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101144

Ihsanullah, Patel F, Khraisheh M, Atieh MA, Laoui T. Novel Aluminum Oxide-Impregnated Carbon Nanotube Membrane for the Removal of Cadmium from Aqueous Solution. Materials. 2017; 10(10):1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101144

Chicago/Turabian StyleIhsanullah, Faheemuddin Patel, Majeda Khraisheh, Muataz Ali Atieh, and Tahar Laoui. 2017. "Novel Aluminum Oxide-Impregnated Carbon Nanotube Membrane for the Removal of Cadmium from Aqueous Solution" Materials 10, no. 10: 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10101144