Characterisation of Asphalt Concrete Using Nanoindentation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

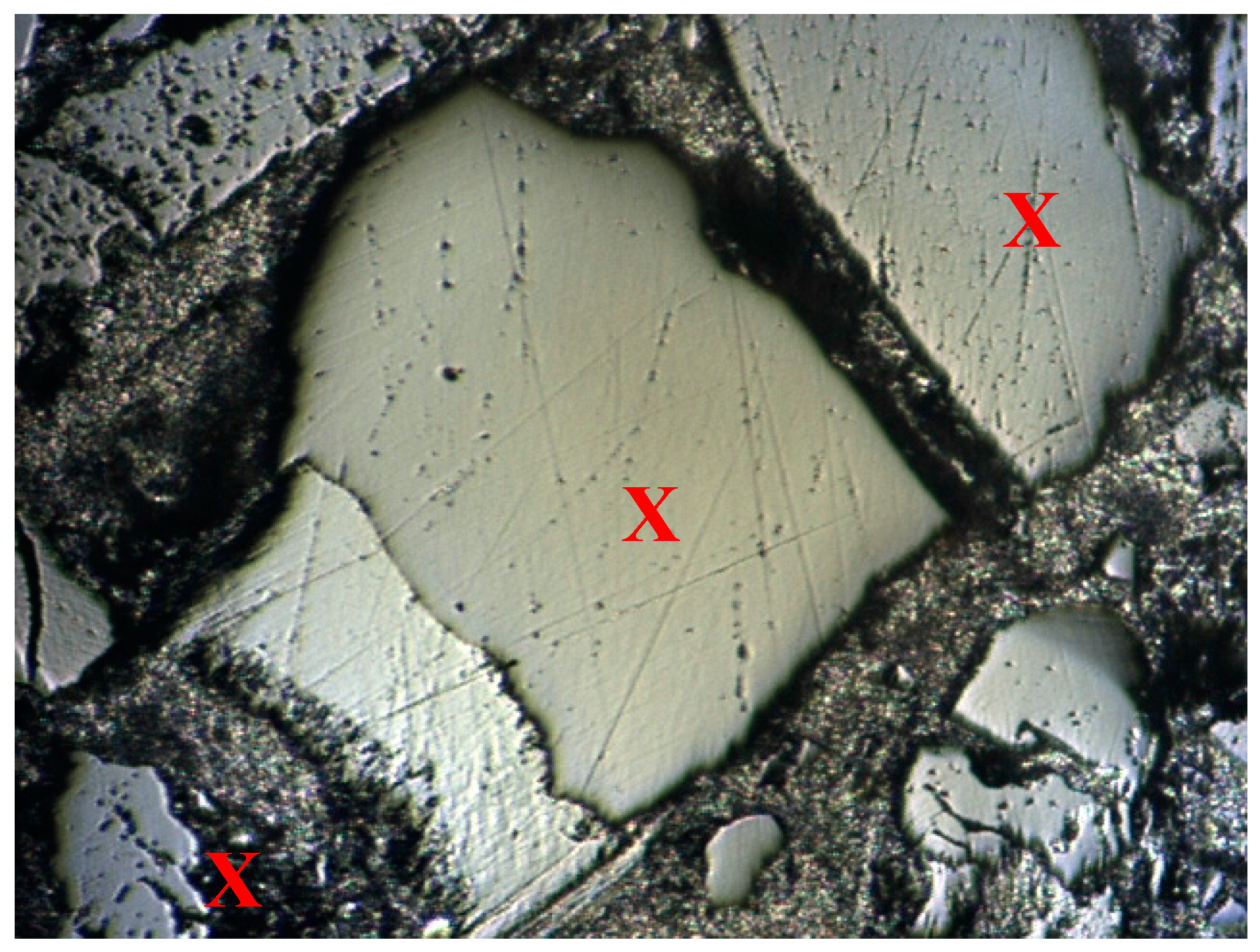

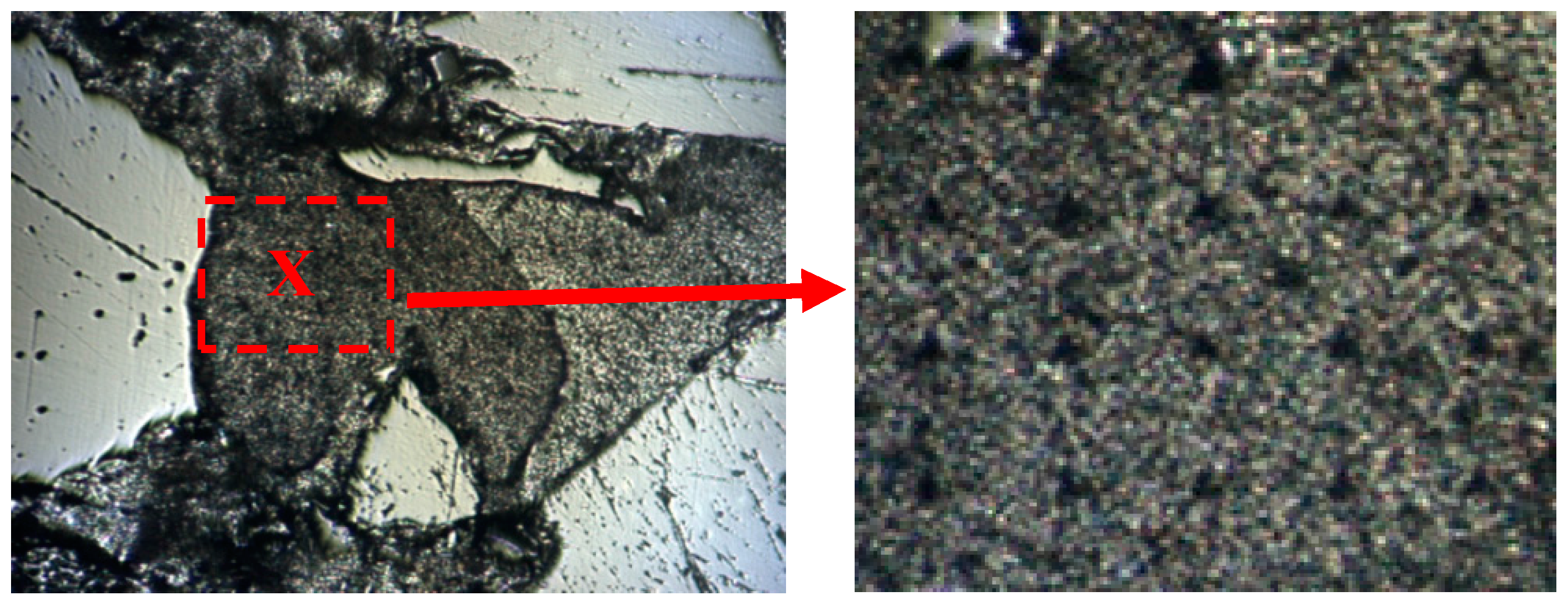

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Nanoindentation

3. Results and Discussion

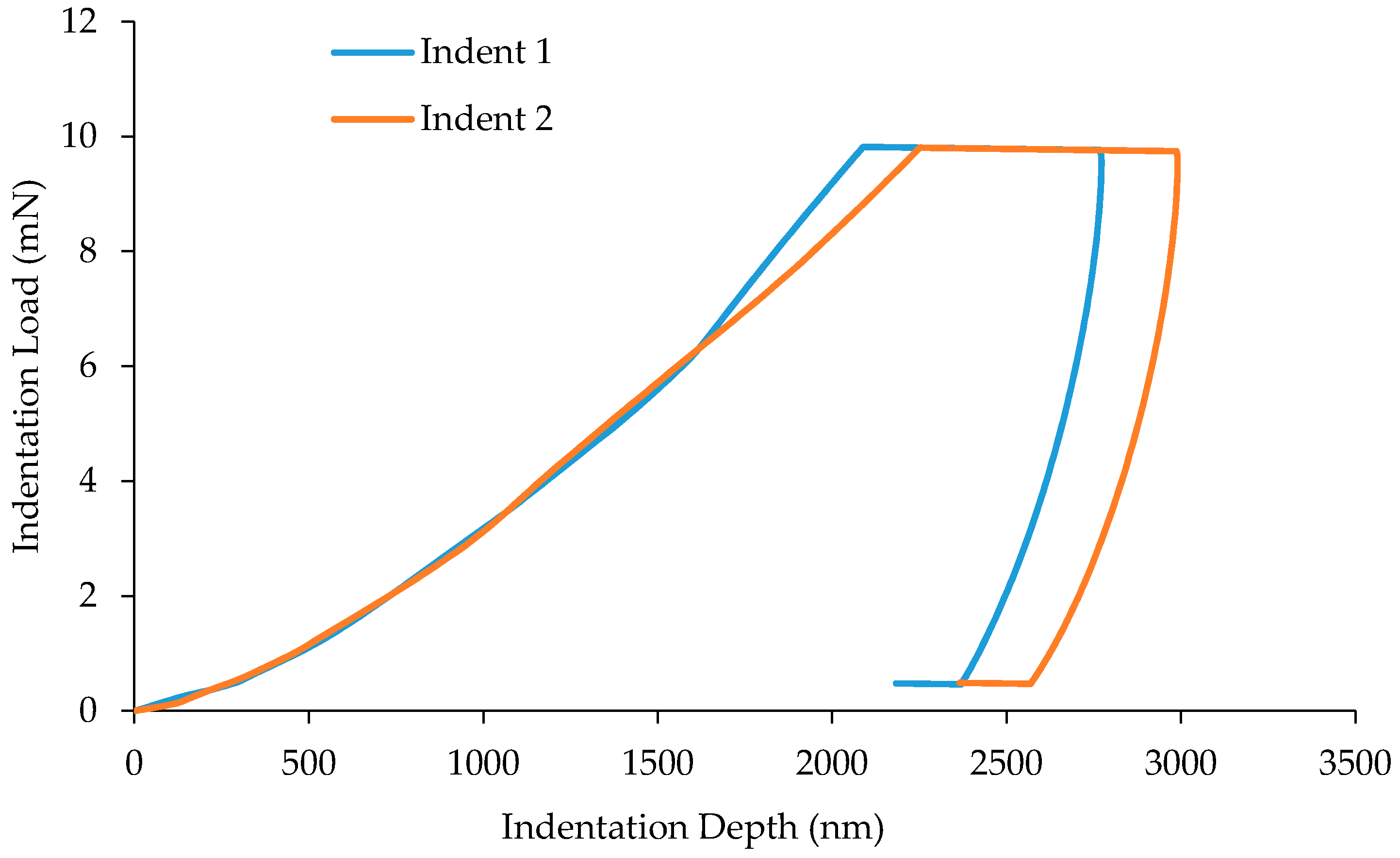

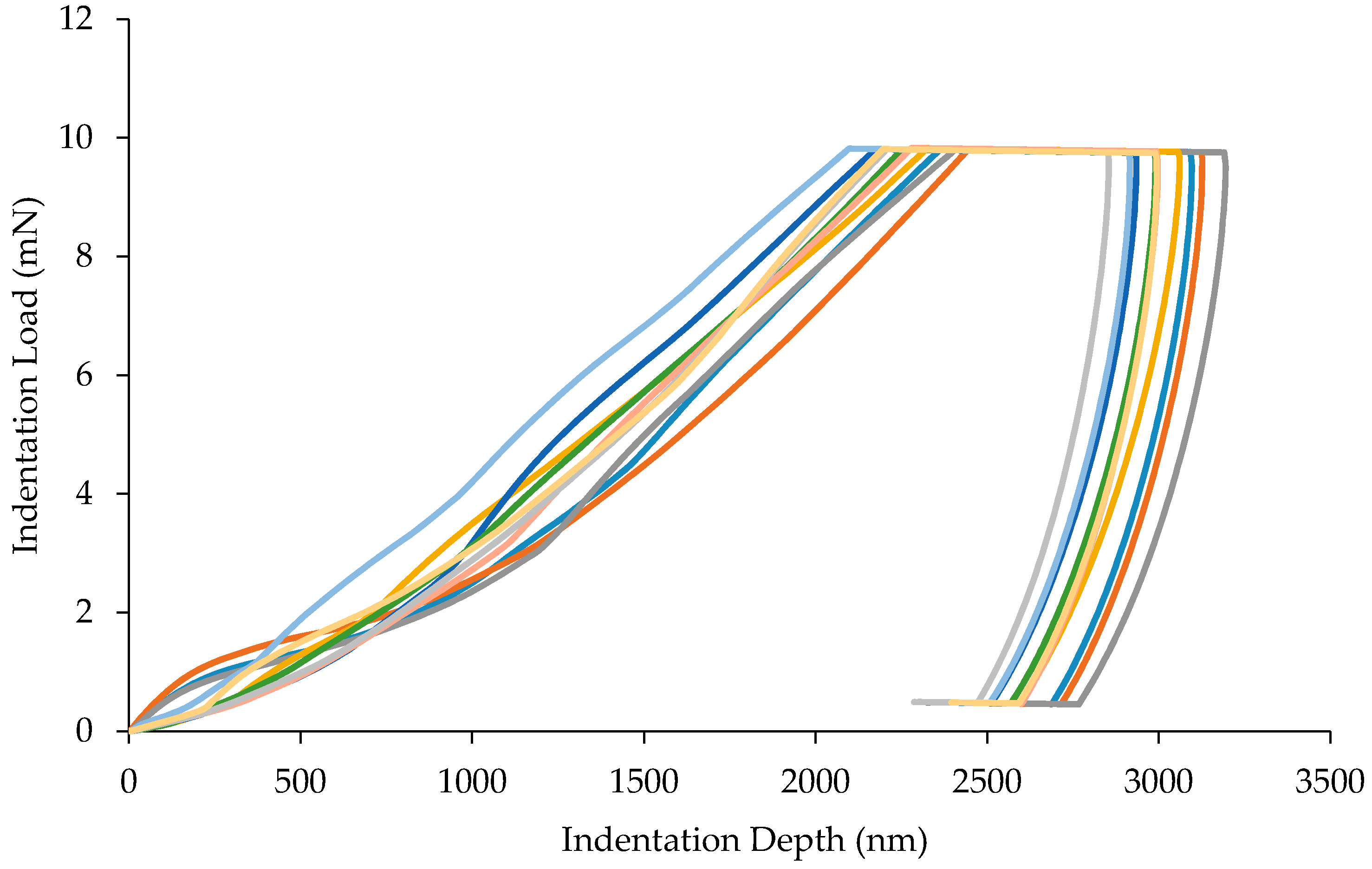

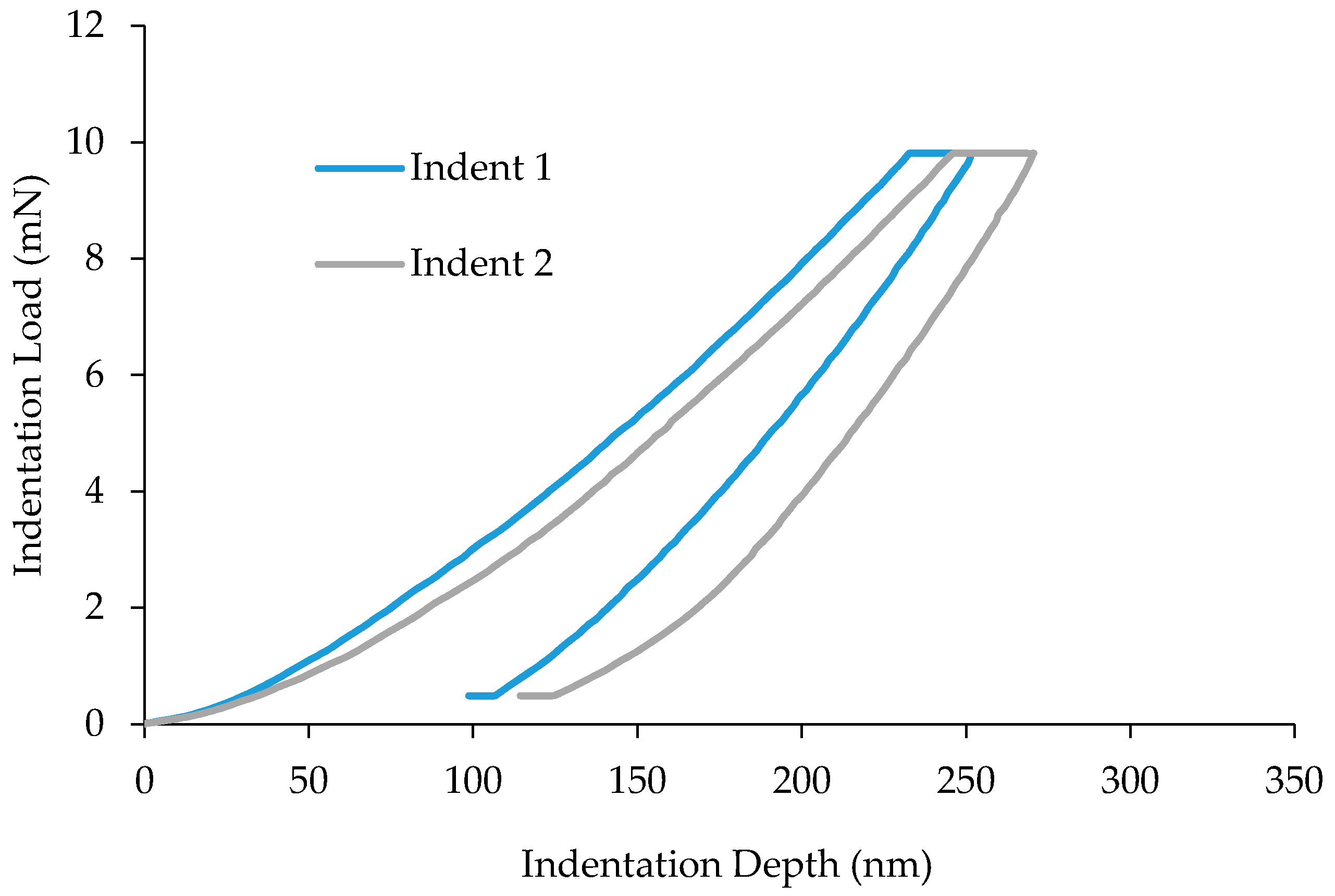

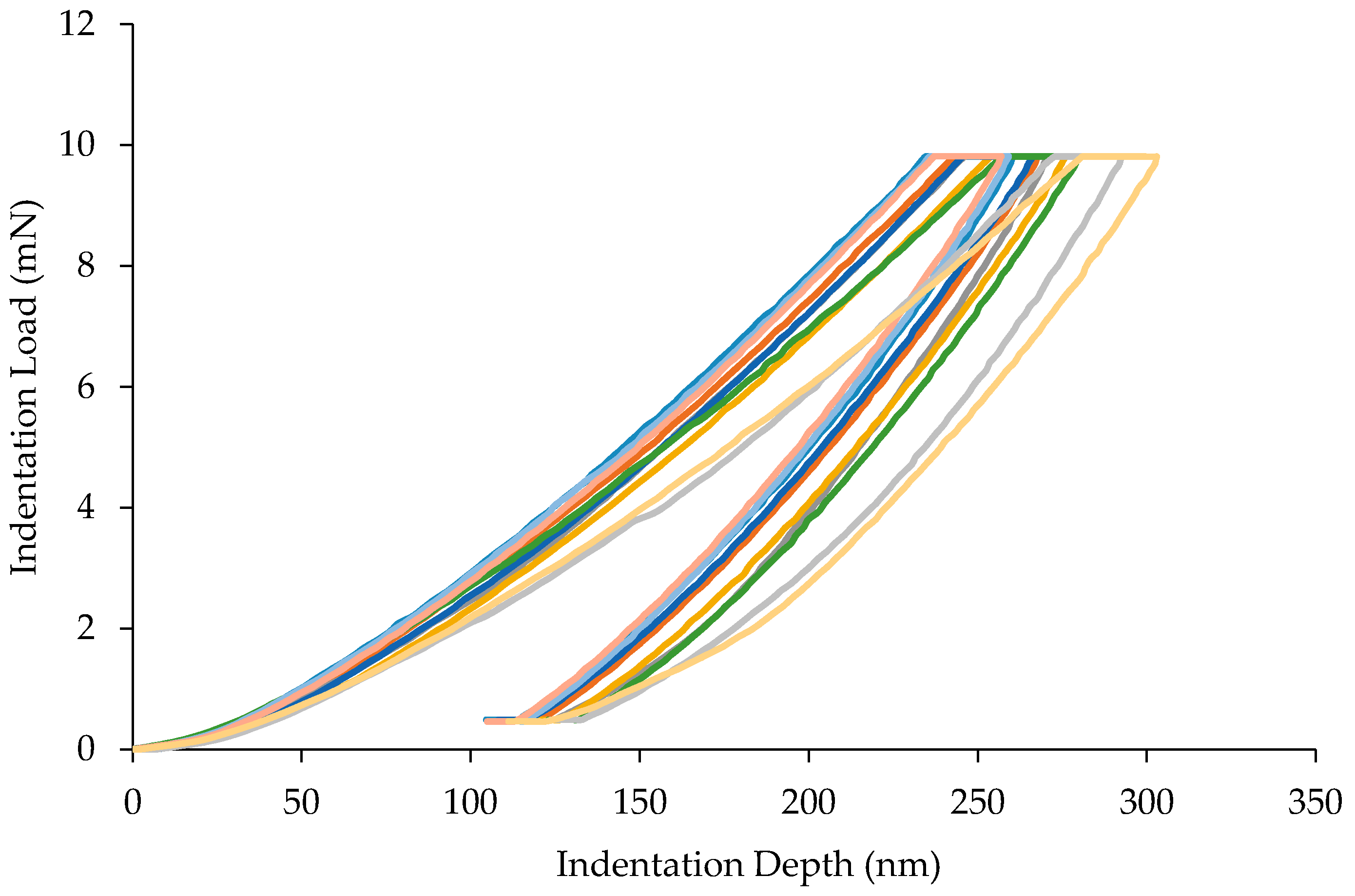

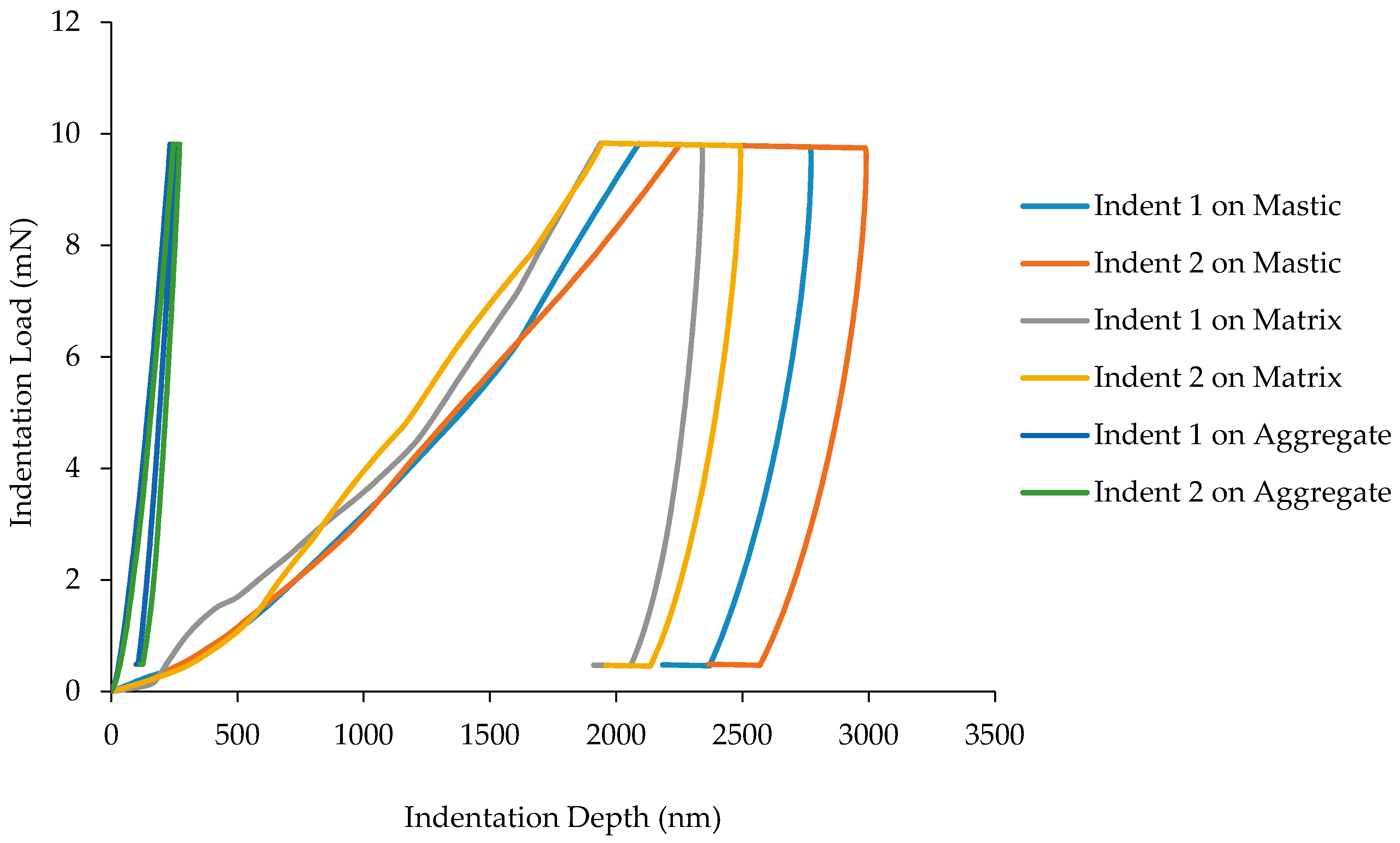

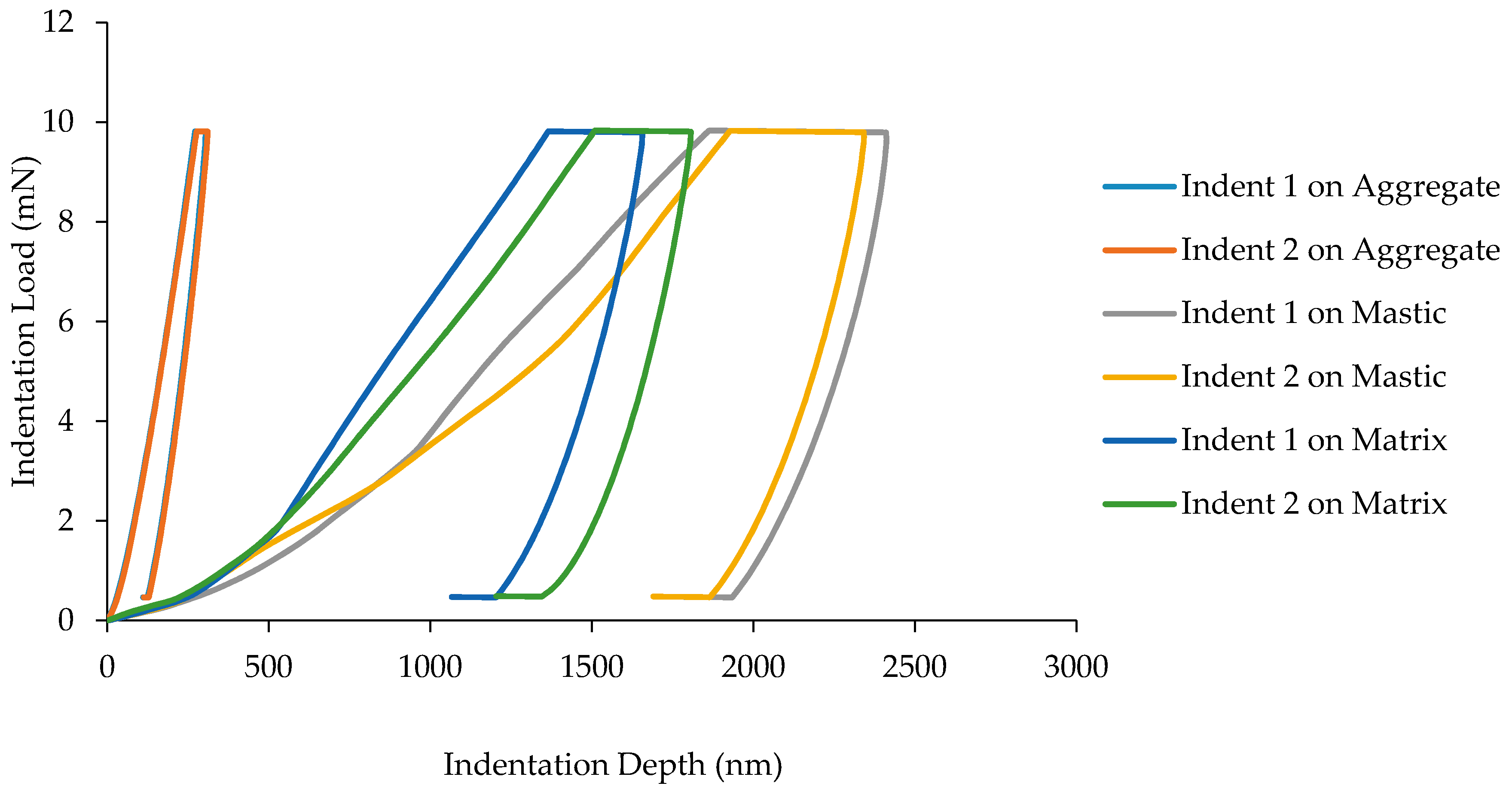

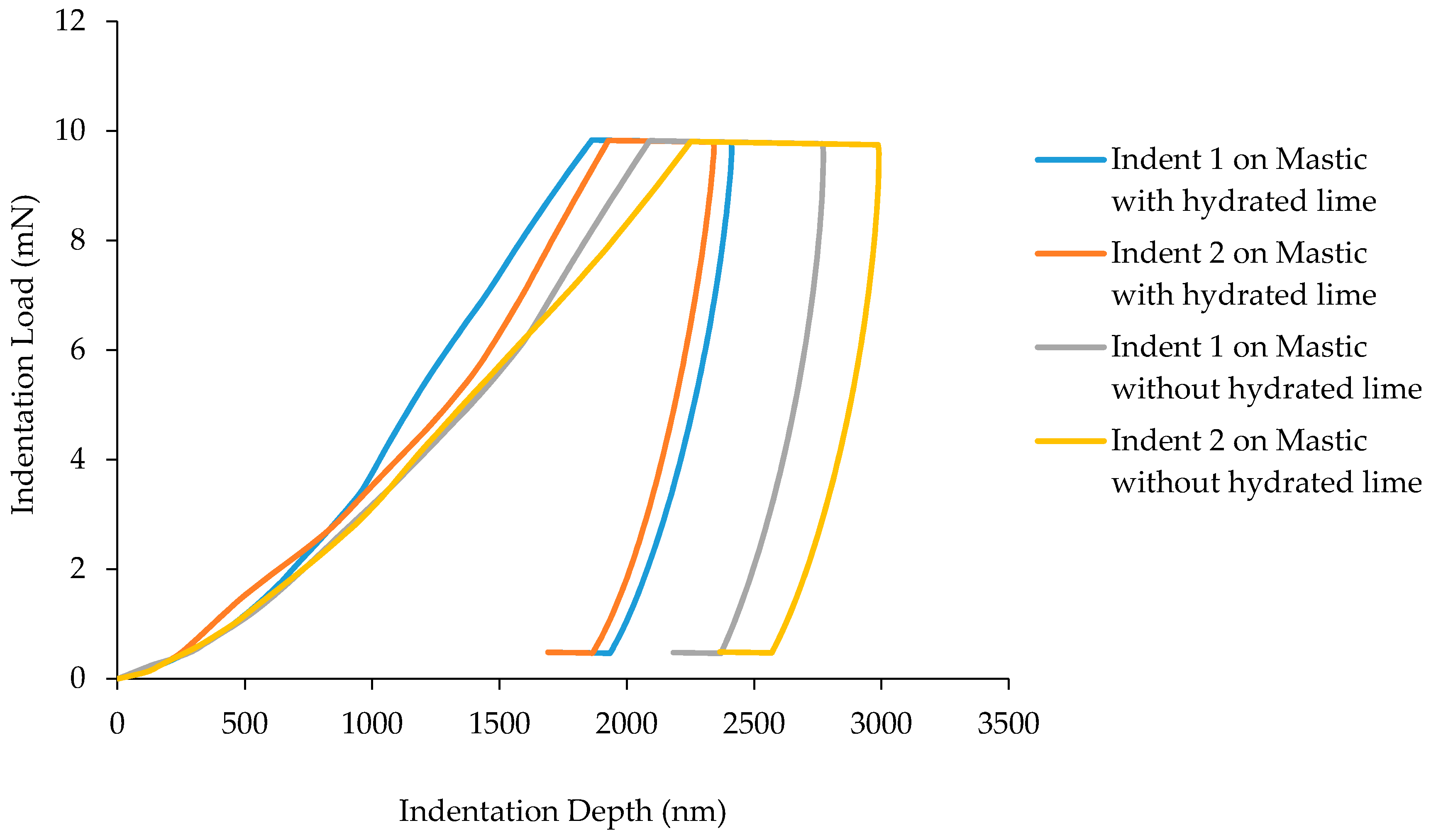

3.1. Load-Displacement Characteristics

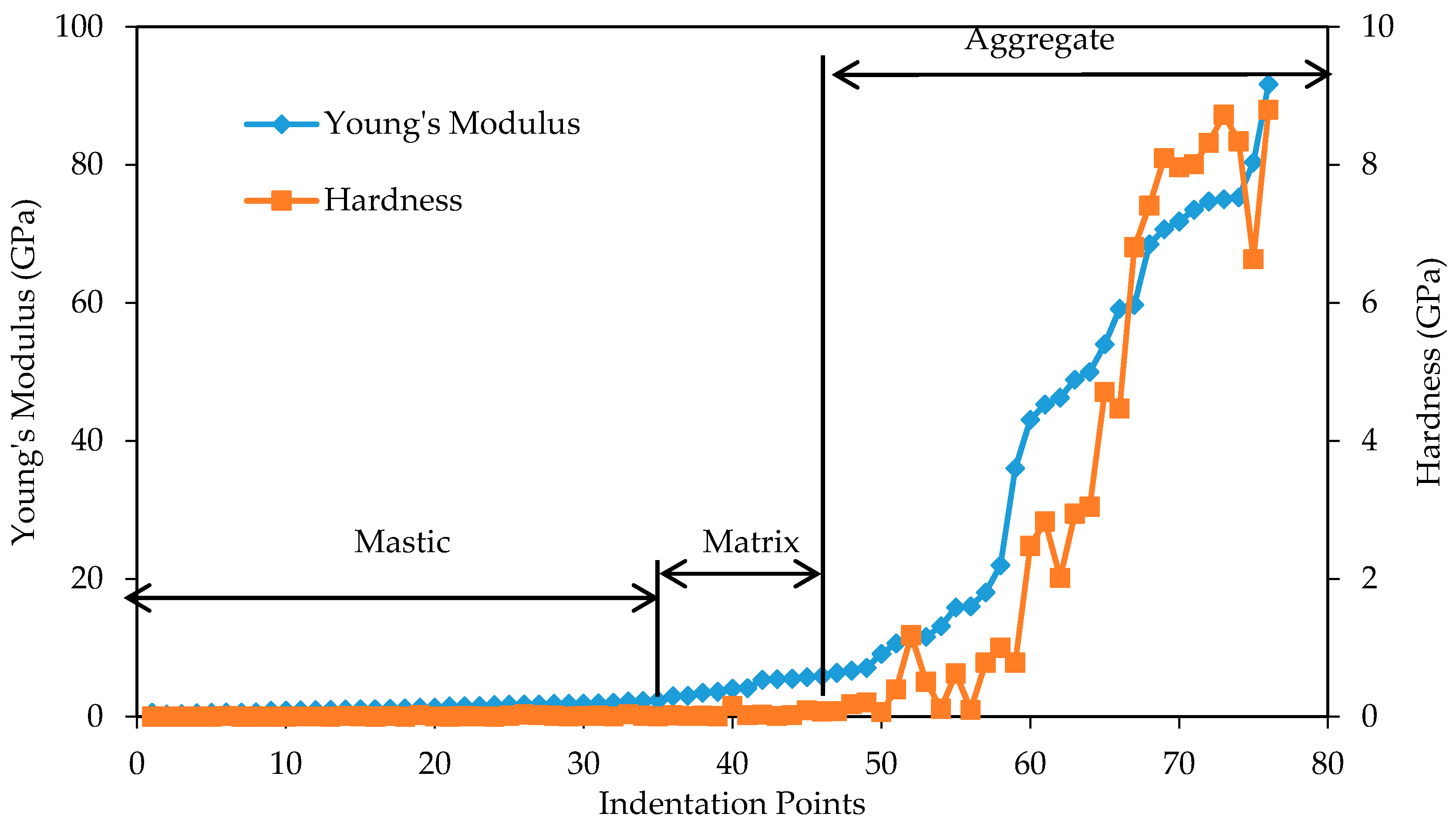

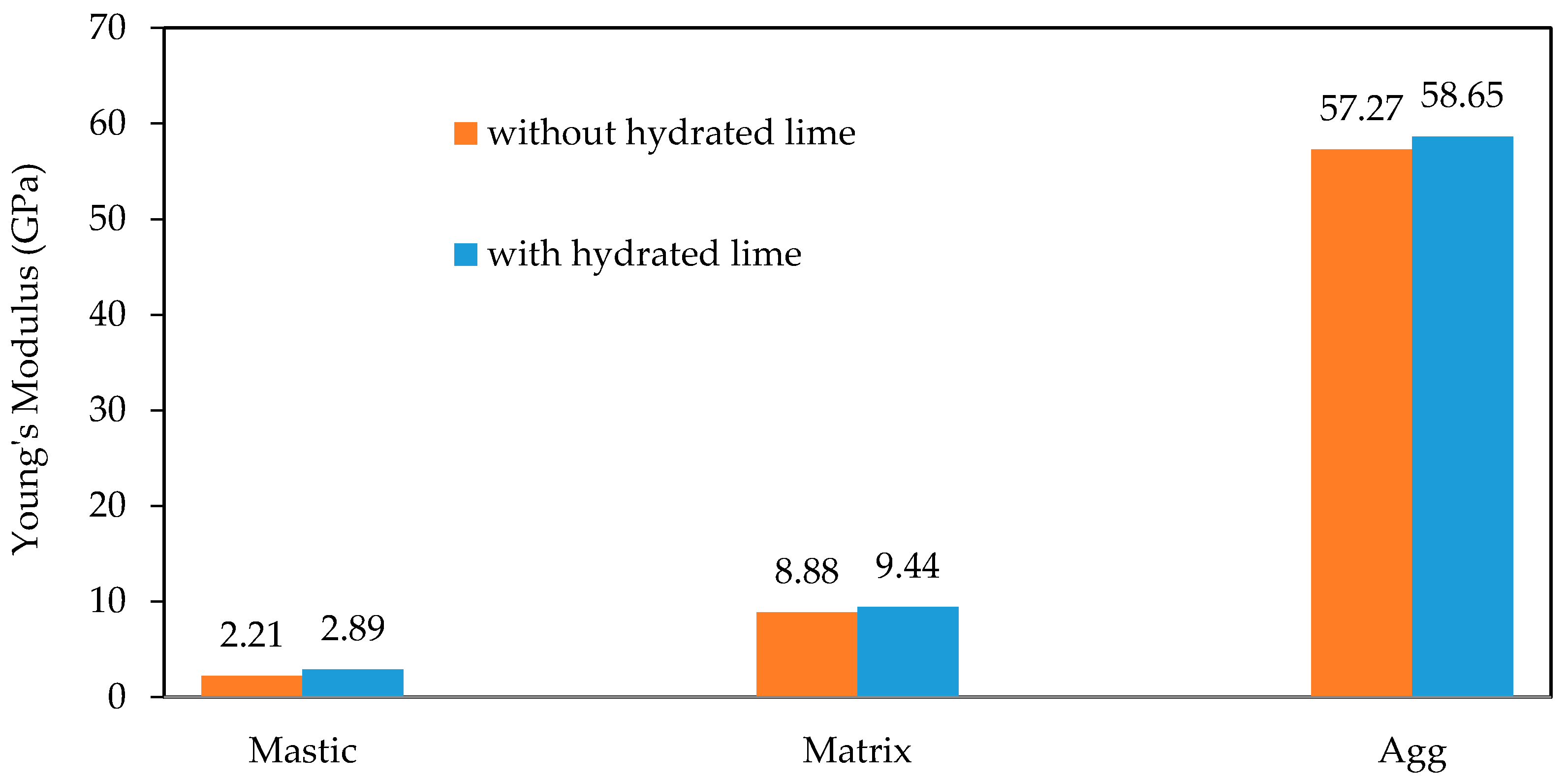

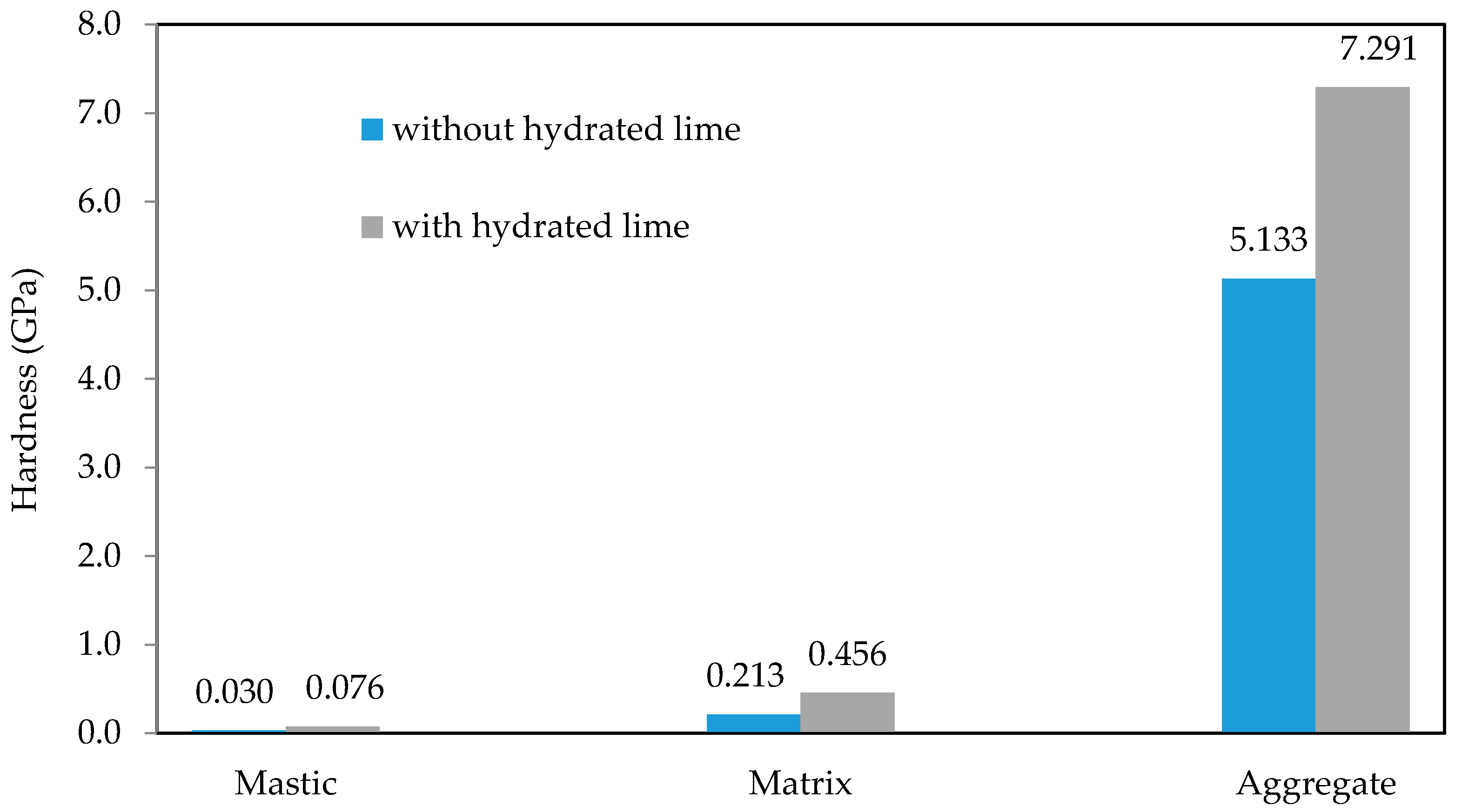

3.2. Nanomechanical Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tarefder, R.A.; Faisal, H.M. Nanoindentation characterization of asphalt concrete aging. J. Nanomech. Micromech. 2014, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, B.J.; Fiori, L.; Pelillo, E. Nano-indentation of polymeric surfaces. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1998, 31, 2395–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.R.; Spearing, S.M. Nanoindentation of neat and in situ polymers in polymer-matrix composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Vlassak, J.J. Numerical study on the measurement of thin film mechanical properties by means of nanoindentation. J. Mater. Res. 2001, 16, 2974–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Little, D.N.; Bhasin, A.; Lytton, R.L. Identification of the composite relaxation modulus of asphalt binder using AFM nanoindentation. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2013, 25, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, H.M.; Tarefder, R.A.; Weldegiorgis, M. Nanoindentation characterization of moisture damage in different phases of asphalt concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2015, 4, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Faisal, H.M.; Tarefder, R.A. Determining effects of moisture in mastic materials using nanoindentation. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarefder, R.A.; Zaman, A.M.; Uddin, W. Determining hardness and elastic modulus of asphalt by nanoindentation. Int. J. Geomech. 2010, 10, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarefder, R.A.; Faisal, H.M. Effects of dwell time and loading rate on the nanoindentation behavior of asphaltic materials. J. Nanomech. Micromech. 2012, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkati, A.; Diew, Y.; Delai, D.S. Effects of fillers on properties of asphalt–concrete mixture. J. Transp. Eng. 2012, 138, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, R.; Al-Rawas, A.; Al-Harthy, A.; Qatan, A. Use of cement bypass dust as filler in asphalt concrete mixtures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2002, 14, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljassar, A.H.; Metwali, S.; Ali, M.A. Effect of filler types on Marshall stability and retained strength of asphalt concrete. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2004, 5, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y. Design and Performance of Stone Mastic Asphalt in Singapore Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gorkem, C.; Sengoz, B. Predicting stripping and moisture induced damage of asphalt concrete prepared with polymer modified bitumen and hydrated lime. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2227–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.C.; Robertson, R.E.; Branthaver, J.F.; Petersen, J.C. Impact of lime modification of asphalt and freeze-thaw cycling on the asphalt-aggregate interaction and moisture resistance to moisture damage. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2005, 17, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, D.N.; Petersen, J.C. Unique effects of hydrated lime filler on the performance-related properties of asphalt cements: Physical and chemical interactions revisited. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2005, 17, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesueur, D.; Little, D.N. Effect of hydrated lime on rheology, fracture and aging of bitumen. Transp. Res. Rec. 1999, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesueur, D.; Petit, J.; Ritter, H.J. The mechanisms of hydrated lime modification of asphalt mixtures: A state-of-the-art review. Road. Mater. Pavement Res. 2013, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veytskin, Y.; Bobko, C.; Castorena, C.; Kim, Y.R. Nanoindentation investigation of asphalt binder and mastic cohesion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 100, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transport and Main Roads Specifications MRTS30 Asphalt Pavements; Technical Specification; Queensland Government: Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 2016; p. 56.

- AS 2150-2005. Hot Mix Asphalt—A Guide to Good Practice; Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia.

- Fischer-Cripps, A.C. Critical review of analysis and interpretation of nanoindentation test data. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 4153–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic-modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials (%) | Base (without Hydrated Lime) | With Hydrated Lime |

|---|---|---|

| 10 mm aggregates | 43.7 | 43.7 |

| 5 mm aggregates | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| Dust | 28.5 | 28.1 |

| Washed dust | 11.4 | 10.4 |

| Hydrated lime | 0 | 1.5 |

| Properties | Values |

|---|---|

| Binder type | C320 |

| Air voids | 3.0–7.0% |

| VMA | ≥16.0% |

| Stability | ≥8.0 kN |

| Flow | 2–4 mm |

| Compaction | 75 blows |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbhuiya, S.; Caracciolo, B. Characterisation of Asphalt Concrete Using Nanoindentation. Materials 2017, 10, 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10070823

Barbhuiya S, Caracciolo B. Characterisation of Asphalt Concrete Using Nanoindentation. Materials. 2017; 10(7):823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10070823

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbhuiya, Salim, and Benjamin Caracciolo. 2017. "Characterisation of Asphalt Concrete Using Nanoindentation" Materials 10, no. 7: 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10070823