Abstract

“Public legal information from all countries and international institutions is part of the common heritage of humanity. Maximizing access to this information promotes justice and the rule of law”. In accordance with the aforementioned declaration on free access to law by legal information institutes of the world, a plethora of legal information is available through the Internet, while the provision of legal information has never before been easier. Given that law is accessed by a much wider group of people, the majority of whom are not legally trained or qualified, diversification techniques should be employed in the context of legal information retrieval, as to increase user satisfaction. We address the diversification of results in legal search by adopting several state of the art methods from the web search, network analysis and text summarization domains. We provide an exhaustive evaluation of the methods, using a standard dataset from the common law domain that we objectively annotated with relevance judgments for this purpose. Our results: (i) reveal that users receive broader insights across the results they get from a legal information retrieval system; (ii) demonstrate that web search diversification techniques outperform other approaches (e.g., summarization-based, graph-based methods) in the context of legal diversification; and (iii) offer balance boundaries between reinforcing relevant documents or sampling the information space around the legal query.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, as a consequence of many open data initiatives, more and more publicly available portals and datasets provide legal resources to citizens, researchers and legislation stakeholders. Thus, legal data that were previously available only to a specialized audience and in “closed” format are now freely available on the Internet.

Portals, such as the EUR-Lex (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/), the European Union’s database of regulations, the on-line version of the United States Code (http://uscode.house.gov/), United Kingdom (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/), Brazil (http://www.lexml.gov.br/) and the Australian one (https://www.comlaw.gov.au/), just to mention a few, serve as an endpoint to access millions of regulations, legislation, judicial cases or administrative decisions. Such portals allow for multiple search facilities, so as to assist users to find the information they need. For instance, the user can perform simple search operations or utilize predefined classificatory criteria, e.g., year, legal basis, subject matter, to find relevant to her/his information needs legal documents.

At the same time, the legal domain generates a huge and ever-increasing amount of open data, thus leveraging the awareness level of legislation stakeholders. Judicial ruling, precedents and interpretations of laws create a big data space with relevant and useful legal resources, while many facts and insights that could help win a legal argument usually remain hidden. For example, it is extremely difficult to search for a relevant case law, by using Boolean queries or the references contained in the judgment. Consider, for example, a patent lawyer who want to find patents as a reference case and submits a user query to retrieve information. A diverse result, i.e., a result containing several claims, heterogeneous statutory requirements and conventions, varying in the numbers of inventors and other characteristics, is intuitively more informative than a set of homogeneous results that contain only patents with similar features. In this paper, we propose a novel way to efficiently and effectively handle similar challenges when seeking information in the legal domain.

Diversification is a method of improving user satisfaction by increasing the variety of information shown to the user. As a consequence, the number of redundant items in a search result list should decrease, while the likelihood that a user will be satisfied with any of the displayed results should increase. There has been extensive work on query results’ diversification (see Section 4), where the key idea is to select a small set of results that are sufficiently dissimilar, according to an appropriate similarity metric.

Diversification techniques in legal information systems can be helpful not only for citizens, but also for law issuers and other legal stakeholders in companies and large organizations. Having a big picture of diversified results, issuers can choose or properly adapt the legal regime that better fits their firms and capital needs, thus helping them operate more efficiently. In addition, such techniques can also help lawmakers, since deep understanding of legal diversification promotes evolution to better and fairer legal regulations for society [1].

In this work, extending our previous work [2], we address result diversification in the legal information retrieval (IR). To this end, in parallel with the search result diversification methods utilized in our previous work (maximal marginal relevance (MMR) [3], Max-sum [4], Max-min [4] and Mono-objective [4]), we extended the methods utilized by incorporating methods introduced for text summarization (LexRank [5] and Biased LexRank [6]) and graph-based ranking (DivRank [7] and Grasshopper [8]). We present the diversification methods utilized with an algorithmic presentation, alongside with a textual explanation of each diversification objective. We evaluate the performance of the above methods on a legal corpus annotated with relevant judgments using metrics employed in TREC Diversity Tasks, fine-tuning separately for each method, trade-off values between finding relevant to the user query documents and diverse documents in the result set.

Our findings reveal that (i) diversification methods, employed in the context of legal IR, demonstrate notable improvements in terms of enriching search results with otherwise hidden aspects of the legal query space and (ii) web search diversification techniques outperform other approaches, e.g., summarization-based, graph-based methods, in the context of legal diversification. Furthermore, our accuracy analysis can provide helpful insights for legal IR systems, wishing to balance between reinforcing relevant documents, result set similarity, or sampling the information space around the query, result set diversity.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the concepts of search diversification and presents diversification algorithms, while Section 3 describes our experimental results and discuss their significance. Section 4 reviews previous work in query result diversification, diversified ranking on graphs and in the field of legal text retrieval, while it stresses the differentiation and contribution of this work. Finally, we draw our conclusions and present future work aspects in Section 5.

2. Legal Document Ranking Using Diversification

At first, we define the problem addressed in this paper and provide an overview of the diversification process. Afterwards, legal document’s features relevant for our work are introduced, and distance functions are defined. Finally, we describe the diversification algorithms used in this work.

2.1. Diversification Overview

Result diversification is a trade-off between finding relevant to the user query documents and diverse documents in the result set. Given a set of legal documents and a query, our aim is to find a set of relevant and representative documents and to select these documents in such a way that the diversity of the set is maximized. More specifically, the problem is formalized as follows:

Definition 1 (Legal document diversification).

Let q be a user query and N a set of documents relevant to the user query. Find a subset of documents that maximize an objective function f that quantifies the diversity of documents in S.

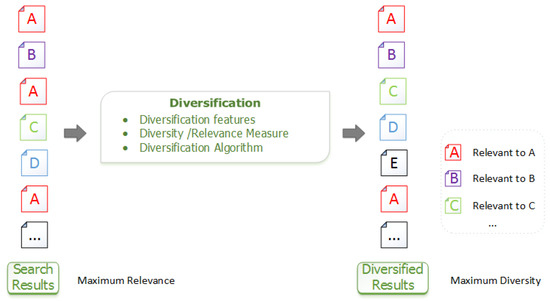

Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow of the diversification process. At the highest level, the user submits his/her query as a way to express an information need and receives relevant documents, as shown in the left column of Figure 1, where different names and colors represent the main aspects/topics of documents. From the relevance-oriented ranking of documents, we derive a diversity-oriented ranking, produced by seeking to achieve both coverage and novelty at the same time. This list is visualized in the right column of Figure 1. Note that Document E was initially hidden in the left column, the relevance-oriented ranked result set list.

Figure 1.

Diversification overview. Each document is identified by name/color representing the main aspects/topics of documents. A diversity-oriented ranked list of the documents is obtained in the right column, through diversification of the relevance-oriented ranked result set list in the left column.

Significant components of the process include:

- Ranking features, features of legal documents that will be used in the ranking process.

- Distance measures, functions to measure the similarity between two legal documents and the relevance of a query to a given document. We note that in this work, as in information retrieval in general [9], the term “distance” is used informally to refer to a dissimilarity measure derived from the characteristics describing the objects.

- Diversification heuristics, heuristics to produce a subset of diverse results.

2.2. Ranking Features/Distance Measures

Typically, diversification techniques measure diversity in terms of content, where textual similarity between items is used in order to quantify information similarity. In the vector space model [10], each document u can be represented as a term vector , where are all of the available terms, and can be any popular indexing schema, e.g., . Queries are represented in the same manner as documents.

Following, we define:

- Document similarity: Various well-known functions from the literature (e.g., Jaccard, cosine similarity, etc.) can be employed for computing the similarity of legal documents. In this work, we choose cosine similarity as a similarity measure; thus, the similarity between documents u and v, with term vectors U and V is:

- Document distance: The distance of two documents is:

- Query document similarity. The relevance of a query q to a given document u can be assigned as the initial ranking score obtained from the IR system, or calculated using the similarity measure, e.g., cosine similarity of the corresponding term vectors:

2.3. Diversification Heuristics

Diversification methods usually retrieve a set of documents based on their relevance scores and then re-rank the documents so that the top-ranked documents are diversified to cover more query subtopics. Since the problem of finding an optimum set of diversified documents is NP-hard, a greedy algorithm is often used to iteratively select the diversified set S.

Let N be the document set, , the relevance of u to the query q, the distance of u and v, with the number of documents to be collected and a parameter used for setting the trade-off between relevance and diversity. In this paper, we focus on the following representative diversification methods:

- MMR: Maximal marginal relevance [3], a greedy method to combine query relevance and information novelty, iteratively constructs the result set S by selecting documents that maximize the following objective function:MMR incrementally computes the standard relevance-ranked list when the parameter and computes a maximal diversity ranking among the documents in N when . For intermediate values of , a linear combination of both criteria is optimized. In MMR Algorithm 1, the set S is initialized with the document that has the highest relevance to the query. Since the selection of the first element has a high impact on the quality of the result, MMR often fails to achieve optimum results.

Algorithm 1 Produce diverse set of results with MMR. Input: Set of candidate results N , size of diverse set k Output: Set of diverse results ▹ Initialize with the highest relevant to the query document Set Set while do Find ▹ Iteratively select document that maximize Equation (5) Set Set end while - Max-sum: The Max-sum diversification objective function [4] aims at maximizing the sum of the relevance and diversity in the final result set. This is achieved by a greedy approximation, Algorithm 2, that selects a pair of documents that maximizes Equation (6) in each iteration.where is a pair of documents, since this objective considers document pairs for insertion. When is odd, in the final phase of the algorithm, an arbitrary element in N is chosen to be inserted in the result set S.Max-sum Algorithm 2, at each step, examines the pairwise distances of the candidate items N and selects the pair with the maximum pairwise distance, to insert into the set of diverse items S.

Algorithm 2 Produce diverse set of results with Max-sum. Input: Set of candidate results N, size of diverse set k Output: Set of diverse results for do Find ▹ Select pair of docs that maximize Equation (6) Set Set end for if k is odd then ▹ If k is odd add an arbitrary document to S end if - Max-min: The Max-min diversification objective function [4] aims at maximizing the minimum relevance and dissimilarity of the selected set. This is achieved by a greedy approximation, Algorithm 3, that initially selects a pair of documents that maximize Equation (7) and then in each iteration selects the document that maximizes Equation (8):Max-min Algorithm 3, at each step, it finds, for each candidate document, its closest document belonging to S and calculates their pairwise distance . The candidate document that has the maximum distance is inserted into S.

Algorithm 3 Produce diverse set of results with Max-min. Input: Set of candidate results N, size of diverse set k Output: Set of diverse results Find ▹ Initially selects documents that maximize Equation (7) Set while do Find ▹ Select document that maximize Equation (8) Set end while - Mono-objective: Mono-objective [4] combines the relevance and the similarity values into a single value for each document. It is defined as:Algorithm 4 approximates the Mono-objective. The algorithm, at the initialization step, calculates a distance score for each candidate document. The objective function weights each document’s similarity to the query with the average distance of the document with the rest of the documents. After the initialization step, where scores are calculated, they are not updated after each iteration of the algorithm. Therefore, each step consists of selecting the document from the remaining candidates set with the maximum score and inserting it into S.

Algorithm 4 Produce diverse set of results with Mono-objective. Input: Set of candidate results N, size of diverse set k Output: Set of diverse results for do ▹ Calculate scores based on Equation (9) end for while do Find ▹ Sort and select documents Set Set end while - LexRank: LexRank [5] is a stochastic graph-based method for computing the relative importance of textual units. A document is represented as a network of inter-related sentences, and a connectivity matrix based on intra-sentence similarity is used as the adjacency matrix of the graph representation of sentences.In our setting, instead of sentences, we use documents that are in the initial retrieval set N for a given query. In this way, instead of building a graph using the similarity relationships among the sentences based on an input document, we utilize document similarity on the result set. If we consider documents as nodes, the result set document collection can be modeled as a graph by generating links between documents based on their similarity score as in Equation (2). Typically, low values in this matrix can be eliminated by defining a threshold so that only significantly similar documents are connected to each other. However, as in all discretization operations, this means information loss. Instead, we choose to utilize the strength of the similarity links. This way we use the cosine values directly to construct the similarity graph, obtaining a much denser, but weighted graph. Furthermore, we normalize our adjacency matrix B, so as to make the sum of each row equal to one.Thus, in LexRank scoring formula Equation (10), Matrix B captures pairwise similarities of the documents, and square matrix A, which represents the probability of jumping to a random node in the graph, has all elements set to , where is the number of documents.LexRank Algorithm 5 applies a variation of PageRank [11] over a document graph. A random walker on this Markov chain chooses one of the adjacent states of the current state with probability or jumps to any state in the graph, including the current state, with probability λ.

Algorithm 5 Produce diverse set of results with LexRank. Input: Set of candidate results N, size of diverse set k Output: Set of diverse results for do ▹ Calculate connectivity matrix based on document similarity Equation (2) end for ▹ Calculate stationary distribution of Equation (10). (Omitted for clarity) while do Find ▹ Sort and select documents Set Set end while - Biased LexRank: Biased LexRank [6] provides for a LexRank extension that takes into account a prior document probability distribution, e.g., the relevance of documents to a given query. The Biased LexRank scoring formula is analogous to LexRank scoring formula Equation (10), with matrix A, which represents the probability of jumping to a random node in the graph, proportional to the query document relevance.Algorithm 5 is also used to produce a diversity-oriented ranking of results with the Biased LexRank method. In Biased LexRank scoring formula Equation (10), we set matrix B as the connectivity matrix based on document similarity for all documents that are in the initial retrieval set N for a given query and matrix A elements proportional to the query document relevance.

- DivRank: DivRank [7] balances popularity and diversity in ranking, based on a time-variant random walk. In contrast to PageRank [11], which is based on stationary probabilities, DivRank assumes that transition probabilities change over time; they are reinforced by the number of previous visits to the target vertex. If is the transition probability from any vertex u to vertex v at time T, is the prior distribution that determines the preference of visiting vertex and is the transition probability from u to v prior to any reinforcement, then,where is the number of times the walk has visited up to time T and,DivRank was originally proposed in a query independent context; thus, it is not directly applicable to the diversification of search results. We introduce a query dependent prior and thus utilize DivRank as a query-dependent ranking schema. In our setting, we use documents that are in the initial retrieval set N for a given query q, create the citation network between those documents and apply the DivRank Algorithm 6 to select divers’ documents in S.

Algorithm 6 Produce diverse set of results with DivRank. Input: Set of candidate results N, size of diverse set k Output: Set of diverse results for do ▹ Connectivity matrix is based on citation network adjacency matrix end for ▹ Calculate stationary distribution of Equation (11). (Omitted for clarity) while do Find ▹ Sort and select documents Set Set end while - Grasshopper: Similar to the DivRank ranking algorithm, it is described in [8]. This model starts with a regular time-homogeneous random walk, and in each step, the vertex with the highest weight is set as an absorbing state.where is the number of times the walk has visited up to time T and,Since Grasshopper and DivRank utilize a similar approach and will ultimately present rather similar results, we utilized Grasshopper distinctively from DivRank. In particularly, instead of creating the citation network of documents belonging to the initial result set, we form the adjacency matrix based on document similarity, as previously explained in LexRank Algorithm 5.

3. Experimental Setup

In this section, we describe the legal corpus we use, the set of query topics and the respective methodology for annotating with relevance judgments for each query, as well as the metrics employed for the evaluation assessment. Finally, we provide the results along with a short discussion.

3.1. Legal Corpus

Our corpus contains 3890 Australian legal cases from the Federal Court of Australia (http://www.fedcourt.gov.au). The cases were originally downloaded from the Australasian Legal Information Institute (http://www.austlii.edu.au) and were used in [12] to experiment with automatic summarization and citation analysis. The legal corpus contains all cases from the Federal Court of Australia spanning from 2006 up to 2009. From the cases, we extracted all text and citation links for our diversification framework. Our index was built using standard stop word removal and Porter stemming, with the log-based indexing technique, resulting in a total of 3890 documents, 9,782,911 terms and 53,791 unique terms.

Table 1 summarizes the testing parameters and their corresponding ranges. To obtain the candidate set N, for each query sample, we keep the elements using cosine similarity and a log-based indexing schema. For the candidate set size , our chosen threshold value, 100, is a typical value used in the literature [13]. Our experimental studies are performed in a two-fold strategy: (i) qualitative analysis in terms of diversification and precision of each employed method with respect to the optimal result set; and (ii) scalability analysis of diversification methods when increasing the query parameters.

Table 1.

Parameters tested in the experiments.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

As the authors of [14] claim that “there is no evaluation metric that seems to be universally accepted as the best for measuring the performance of algorithms that aim to obtain diverse rankings”, we have chosen to evaluate diversification methods using various metrics employed in TREC Diversity Tasks (http://trec.nist.gov/data/web10.html). In particular, we report:

- a-nDCG: The a-normalized discounted cumulative gain [15] metric quantifies the amount of unique aspects of the query q that are covered by the ranked documents. We use , as typical in TREC evaluation.

- ERR-IA: Expected reciprocal rank-intent aware [16] is based on inter-dependent ranking. The contribution of each document is based on the relevance of documents ranked above it. The discount function is therefore not just dependent on the rank, but also on the relevance of previously ranked documents.

- S-recall: Subtopic-recall [17] is the number of unique aspects covered by the results, divided by the total number of aspects. It measures the aspect coverage for a given result list at depth k.

3.3. Relevance Judgments

Evaluation of diversification requires a data corpus, a set of query topics and a set of relevance judgments, preferably assessed by domain experts for each query. One of the difficulties in evaluating methods designed to introduce diversity in the legal document ranking process is the lack of standard testing data. While TREC added a diversity task to the web track in 2009, this dataset was designed assuming a general web search, and so, it is not possible to adapt it to our setting. Having only the document corpus, we need to define: (a) the query topics; (b) a method to derive the subtopics for each topic; and (c) a method to annotate the corpus for each topic. In the absence of a standard dataset specifically tailored for this purpose, we looked for an objective way to evaluate and assess the performances of various diversification methods on our corpus. We do acknowledge the fact that the process of automatic query generation is at best an imperfect approximation of what a real person would do.

To this end, we have employed the following way to annotate our corpus with relevance judgments for each query:

User profiles/queries: The West American Digest System is a taxonomy of identifying points of law from reported cases and organizing them by topic and key number. It is used to organize the entire body of American law. We used the West Law Digest Topics as candidate user queries. In other words, each topic was issued as a candidate query to our retrieval system. Outlier queries, whether too specific/rare or too general, were removed using the interquartile range, below or above values and , sequentially in terms of the number of hits in the result set and the score distribution for the hits, demanding in parallel a minimum coverage of results. In total, we kept 289 queries. Table 2 provides a sample of the topics we further consider as user queries.

Table 2.

West Law Digest Topics as user queries.

Query assessments and ground-truth: For each topic/query, we kept the results. An LDA [18] topic model, using an open source implementation (http://mallet.cs.umass.edu/), was trained on the results for each query. Topic modeling gives us a way to infer the latent structure behind a collection of documents since each trained topic is a set of keywords with corresponding weights. Table 3 provides a sample of the top keywords for each topic based on the result set for User Query 1: Abandoned and Lost Property .

Table 3.

Top key words for topics for documents on the result set for Query 1: Abandoned and Lost Property.

Based on the resulting topic distribution, with an acceptance threshold of 20%, we access a document as relevant for an topic/aspect. The chosen threshold value, 20%, in the outcome of the LDA method to annotate the corpus for each topic affects the density of our topic/aspect distribution and not the generalizability of the proposed approach or the evaluation outcome. We performed experiments with other settings, i.e., 10% and 30% achieving comparable results. We do acknowledge the fact that if we had chosen a threshold based on interquartile range, as we did in the “user profiles/queries” paragraph, the aforementioned threshold would sound less ad hoc. Nevertheless, this would come at the expense of increasing the complexity both of the paper and the system code.

Table 4 provides a sample of the topic distribution for User Query 1: Abandoned and Lost Property. For the data given in Table 4, based on the relative proportions, with an acceptance threshold of 20%, we can infer that Document Number 08_711 is relevant for Topics 1 and 2, while Document Number 07_924 is relevant for Topics 1 and 5.

Table 4.

Topic composition for five random documents on the result set for Query 1: Abandoned and Lost Property.

In other words from the corresponding topic model distribution, we acquire binary assessments for each query and document in the result set. Thus, using LDA, we create our ground-truth data consisting of binary aspect assessments for each query.

We have made available our complete dataset, ground-truth data, queries and relevance assessments in standard TREC format (qrel files), so as to enhance collaboration and contribution with respect to diversification issues in legal IR (https://github.com/mkoniari/LegalDivEval).

3.4. Results

As a baseline to compare diversification methods, we consider the simple ranking produced by cosine similarity and log-based indexing schema. For each query, our initial set N contains the query results. The interpolation parameter is tuned in 0.1 steps separately for each method. We present the evaluation results for the methods employed, using the aforementioned evaluation metrics, at cut-off values of 5, 10, 20 and 30, as typical in TREC evaluations. Results are presented with fixed parameter n = . Note that each of the diversification variations is applied in combination with each of the diversification algorithms and for each user query.

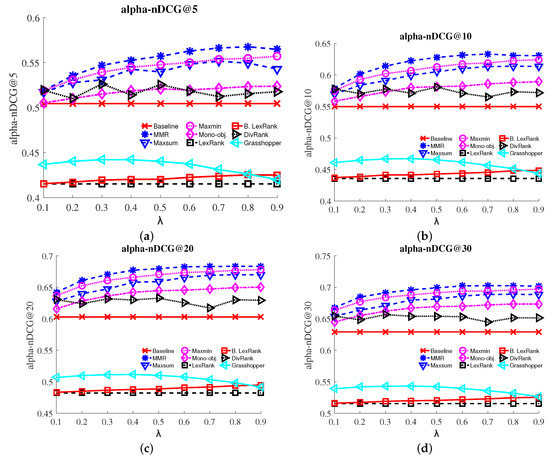

Figure 2 shows the a-normalized discounted cumulative gain (a-nDCG) of each method for different values of λ. Interestingly, web search result diversification methods (MMR, Max-sum, Max-min and Mono-objective) outperformed the baseline ranking, while text summarization methods (LexRank, Biased LexRank and Grasshopper, as it was utilized without a network citation graph) failed to improve the baseline ranking performing lower than the baseline ranking at all levels across all metrics. Graph-based methods’ (DivRank) results vary across the different values of λ. We attribute this finding to the extreme sparse network of citations since our dataset covers a short time period (three years).

Figure 2.

a-Normalized discounted cumulative gain (a-nDCG) at various levels @5, @10, @20, @30 for baseline, MMR, Max-sum, Max-min, Mono-objective, LexRank, Biased LexRank, DivRank and Grasshopper methods. (a) alpha-nDCG@5; (b) alpha-nDCG@10; (c) alpha-nDCG@20; (d) alpha-nDCG@30. (Best viewed in color.)

The trending behavior of MMR, Max-min and Max-sum is very similar, especially at levels @10, and @20, while at level @5, Max-min and Max-sum presented nearly identical a-nDCG values in many λ values (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.7). Finally, MMR constantly achieves better results with respect to the rest of the methods, followed by Max-min and Max-sum. Mono-objective, despite the fact that it performs better than the baseline in all λ values, still always presents a lower performance when compared to MMR, Max-min and Max-sum. It is clear that web search result diversification approaches (MMR, Max-sum, Max-min and Mono-objective) tend to perform better than the selected baseline ranking method. Moreover, as λ increases, preference for diversity, as well as a-nDCG accuracy increase for all tested methods.

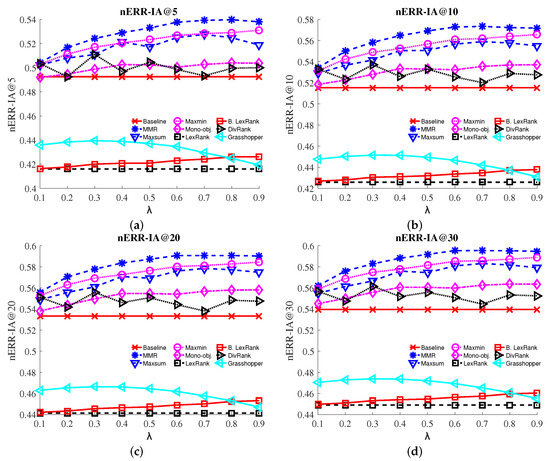

Figure 3 depicts the normalized expected reciprocal rank-intent aware (nERR-IA) plots for each method with respect to different values of λ. It is clear that web search result diversification approaches (MMR, Max-sum, Max-min and Mono-objective) tend to perform better than the selected baseline ranking method. Moreover, as λ increases, preference for diversity, as well as nERR-IA accuracy increase for all tested methods. Text summarization methods (LexRank, Biased LexRank) and Grasshopper once again failed to improve the baseline ranking at all levels across all metrics, while as in a-nDCG plots, DivRank results vary across the different values of λ. MMR constantly achieves better results with respect to the rest of the methods. We also observed that Max-min tends to perform better than Max-sum. There were a few cases where both methods presented nearly similar performance, especially in lower recall levels (e.g., for nERR-IA@5 when λ equals 0.1, 0.4, 0.6, 0.7). Once again, Mono-objective presents a lower performance when compared to MMR, Max-min and Max-sum for the nERR-IA metric for all λ values applied.

Figure 3.

Normalized expected reciprocal rank-intent aware (nERR-IA) at various levels @5, @10, @20, @30 for baseline and the MMR, Max-sum, Max-min, Mono-objective, LexRank, Biased LexRank, DivRank and Grasshopper methods. (a) nERR-IA@5; (b) nERR-IA@10; (c) nERR-IA@20; (d) nERR-IA@30. (Best viewed in color.)

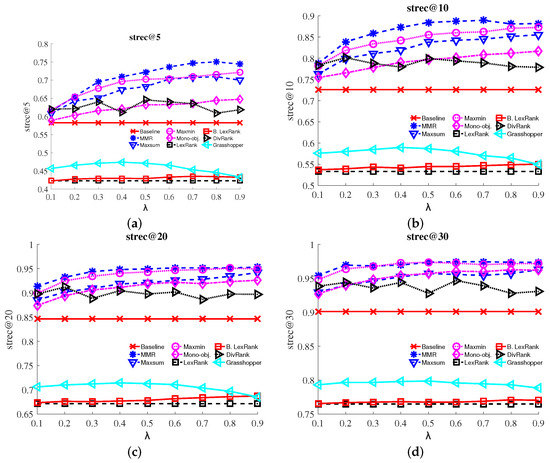

Figure 4 shows the subtopic-recall (S-recall) at various levels @5, @10, @20, @30 of each method for different values of λ. It is clear that the web search result diversification methods (MMR, Max-sum, Max-min and Mono-objective) tend to perform better than the baseline ranking. As λ increases, preference to diversity increases for all methods, except MMR. Subtopic-recall accuracy of all methods, except MMR, increases when increasing λ. For lower levels (e.g., @5, @10), MMR clearly outperforms other methods, while for upper levels (e.g., @20, @30), MMR and Max-min scores are comparable. We also observe that Max-min tends to perform better than Max-sum, which in turn constantly achieves better results than Mono-objective. Finally, LexRank, Biased LexRank and Grasshopper approaches fail to improve the baseline ranking at all levels across all metrics. Overall, we noticed a similar trending behavior with the ones discussed for Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Subtopic recall (S-recall) at various levels @5, @10, @20, @30 for the baseline and the MMR, Max-sum, Max-min, Mono-objective, LexRank, Biased LexRank, DivRank and Grasshopper methods. (a) S-recall@5; (b) S-recall@10; (c) S-recall@20; (d) S-recall@30. (Best viewed in color.)

In summary, among all of the results, we note that the trends in the graphs look very similar. Clearly enough, the utilized web search diversification methods (MMR, Max-sum, Max-min, Mono-objective) and DivRank statistically significantly, using the paired two-sided t-test, outperform the baseline method, offering legislation stakeholders broader insight with respect to their information needs. Furthermore, trends across the evaluation metric graphs highlight balance boundaries for legal IR systems between reinforcing relevant documents or sampling the information space around the legal query.

Table 5 summarizes the average results of the diversification methods. Statistically-significant values, using the paired two-sided t-test with are denoted with and with with .

Table 5.

Retrieval performance of the tested algorithms with interpolation parameter tuned in 0.1 steps for and . The highest scores are shown in bold. Statistically-significant values, using the paired two-sided t-test with are denoted with and with with .

The effectiveness of diversification methods is also depicted in Table 6, which illustrates the result sets for three example queries, using our case law dataset ( and ) with (no diversification), (light diversification), (moderate diversification) and (high diversification). Only MMR results are shown since, in almost all variations, it outperforms other approaches. Due to space limitations, we show the case title for each entry. The hyperlink for the full text for each entry can be formed using the format (http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/FCA/{year}/{docNum}.html) and substituting the given values in the Table 6. For example, for the first entry of the Table 6 the corresponding hyperlink, substituting values 2008 and 1503 for and is (http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/FCA/2008/1503.html).

Table 6.

Result sets (document titles for three example queries, using the dataset ( and ) with (no diversification), (light diversification), (moderate diversification) and (high diversification).

When , the result set contains the top-five elements of S ranked with the similarity scoring function. The result sets with no diversification contain several almost duplicate elements, defined by terms in the case title. As λ increases, less “duplicates” are found in the result set, and the elements in the result set “cover” many more subjects again, as defined by terms in the case title. We note that the result set with high diversification contains elements that have almost all of the query terms, as well as other terms indicating that the case is related to different subjects among the other cases in the result set.

4. Related Work

In this section, we first present related work on query result diversification, afterwards on diversified ranking on graphs and then on legal text retrieval techniques.

4.1. Query Result Diversification

Result diversification approaches have been proposed as a means to tackle ambiguity and redundancy, in various problems and settings, e.g., diversifying historical archives [19], diversifying user comments on news articles [20], diversifying microblog posts [21,22], diversifying image retrieval results [23], diversifying recommendations [24], utilizing a plethora of algorithms and approaches, e.g., learning algorithms [25], approximation algorithms [26], page rank variants [27] and conditional probabilities [28].

Users of (web) search engines typically employ keyword-based queries to express their information needs. These queries are often underspecified or ambiguous to some extent [29]. Different users who pose exactly the same query may have very different query intents. Simultaneously, the documents retrieved by an IR system may reflect superfluous information. Search result diversification aims to solve this problem, by returning diverse results that can fulfill as many different information needs as possible. Published literature on search result diversification is reviewed in [30,31].

The maximal marginal relevance criterion (MMR), presented in [3], is one of the earliest works on diversification and aims at maximizing relevance while minimizing similarity to higher ranked documents. Search results are re-ranked as the combination of two metrics, one measuring the similarity among documents and the other the similarity between documents and the query. In [4], a set of diversification axioms is introduced, and it is proven that it is not possible for a diversification algorithm to satisfy all of them. Additionally, since there is no single objective function suitable for every application domain, the authors propose three diversification objectives, which we adopt in our work. These objectives differ in the level where the diversity is calculated, e.g., whether it is calculated per separate document or on the average of the currently-selected documents.

In another approach, researchers utilized explicit knowledge so as to diversify search results. In [32], the authors proposed a diversification framework, where the different aspects of a given query are represented in terms of sub-queries, and documents are ranked based on their relevance to each sub-query, while in [33] the authors proposed a diversification objective that tries to maximize the likelihood of finding a relevant document in the positions given the categorical information of the queries and documents. Finally, the work described in [34] organizes user intents in a hierarchical structure and proposes a diversification framework to explicitly leverage the hierarchical intent.

The key difference between these works and the ones utilized in this paper is that we do not rely on external knowledge, e.g., taxonomy, query logs to generate diverse results. Queries are rarely known in advance, thus probabilistic methods to compute external information are not only expensive to compute, but also have a specialized domain of applicability. Instead, we evaluate methods that rely only on implicit knowledge of the legal corpus utilized and on computed values, using similarity (relevance) and diversity functions in the data domain.

4.2. Diversified Ranking on Graphs

Many network-based ranking approaches have been proposed to rank objects according to different criteria [35], and recently, diversification of the results has attracted attention. Research is currently focused on two directions: a greedy vertex selection procedure and a vertex-reinforced random walk. The greedy vertex selection procedure, at each iteration, selects and removes from the graph the vertex with maximum random walk-based ranking score. One of the earlier algorithms that addresses diversified ranking on graphs by vertex selection with absorbing random walks is Grasshopper [8]. A diversity-focused ranking methodology, based on reinforced random walks, was introduced in [7]. Their proposed model, DivRank, incorporates the rich-gets-richer mechanism to PageRank [11] with reinforcements on transition probabilities between vertices. We utilize these approaches in our diversification framework considering the connectivity matrix of the citation network between documents that are relevant for a given user query.

4.3. Legal Text Retrieval

With respect to legal text retrieval that traditionally relies on external knowledge sources, such as thesauri and classification schemes, various techniques are presented in [36]. Several supervised learning methods have been proposed to classify sources of law according to legal concepts [37,38,39]. Ontologies and thesauri have been employed to facilitate information retrieval [40,41,42,43] or to enable the interchange of knowledge between existing legal knowledge systems [44]. Legal document summarization [45,46,47] has been used as a way to make the content of the legal documents, notably cases, more easily accessible. We also utilize state of the art summarization algorithms, but under a different objective: we aim to maximize the diversity of the result set for a given query.

Finally, a similar approach with our work is described in [48], where the authors utilize information retrieval approaches to determine which sections within a bill tend to be outliers. However, our work differs in the sense that we maximize the diversify of the result set, rather than detect section outliers within a specific bill.

In another line of work, citation analysis has been used in the field of law to construct case law citation networks [49]. Case documents usually cite previous cases, which in turn may have cited other cases, and thus, a network is formed over time with these citations between cases. Case law citation networks contain valuable information, capable of measuring legal authority [50], identifying authoritative precedent (the legal norm inherited from English common law that encourages judges to follow precedent by letting the past decision stand) [51], evaluating the relevance of court decisions [52] or even assisting with summarizing legal cases [53], thus showing the effectiveness of citation analysis in the case law domain. While the American legal system has been the one that has undergone the widest series of studies in this direction, recently, various researchers applied network analysis in the civil law domain, as well. The authors of [54] propose a network-based approach to model the law. Network analysis techniques were also employed in [55], demonstrating an online toolkit allowing legal scholars to apply network analysis and visual techniques to the entire corpus of EU case law. In this work, we also utilize citation analysis techniques and construct the legislation network, as to cover a wide range of possible aspects of a query.

This paper is an extended version of our paper [2], where we originally introduced the concept of diversifying legal information retrieval results with the goal of evaluating the potential of results diversification in the field of legal information retrieval. We adopted various methods from the literature that where introduced for search result diversification (MMR [3], Max-sum [4], Max-min [4] and Mono-objective [4]) and evaluated the performance of the above methods on a legal corpus objectively annotated with relevance judgments. In our work [56], we address result diversification in the legal IR. To this end, we analyze the impact of various features in computing the query-document relevance and document-document similarity scores and introduce legal domain-specific diversification criteria.

In this work, extending our previous work presented in [2], we extended the methods utilized by incorporating methods introduced for text summarization (LexRank [5] and Biased LexRank [6]) and graph-based ranking (DivRank [7] and Grasshopper [8]) in parallel with the search result diversification methods utilized in our previous work (MMR, Max-sum, Max-min and Mono-objective). We adopted the text summarization and graph-based ranking methods in our diversification schema, and additionally, we utilized various features of our legal dataset.

In detail, text summarization methods (LexRank and Biased LexRank) were originally proposed for computing the relative importance of textual units within a document for assisting summarization tasks. They utilize a document as a graph with vertices consisting of its sentences and edges formed among the vertices based on the sentence textual similarity. To utilize such an approach in our diversification scenario, we: (i) introduce a query-dependent prior, since in our approach, we utilize documents that are in the initial retrieval set N for a given query; and (ii) we build a graph using the document similarity on the result set. If we consider documents as nodes, the result set document collection can be modeled as a graph by generating links between documents based on their similarity score. Analogously to adopting graph-based ranking methods (DivRank and Grasshopper) in our setting, we: (i) introduce a query-dependent prior, since these methods were originally proposed in a query independent context, thus not directly applicable to the diversification of search results; and (ii) we use documents that are in the initial retrieval set N for a given query q and create the citation network between those documents based on the features of the legal dataset we use (prior citation analysis).

Furthermore, we complemented the presentation of the diversification methods utilized with an algorithmic presentation, alongside a textual explanation of each diversification objective, evaluated all of the methods using a real dataset from the common law domain and performed an exhaustive accuracy analysis, fine-tuning separately for each method, trade-off values between finding relevant to the user query documents and diverse documents in the result set. Additionally, we identified statistically-significant values in the retrieval performance of the tested algorithms using the paired two-sided t-test.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we studied the problem of diversifying results in legal documents. We adopted and compared the performance of several state of the art methods from the web search, network analysis and text summarization domains so as to handle the problems challenges. We evaluated all of the methods using a real dataset from the common law domain that we objectively annotated with relevance judgments for this purpose. Our findings reveal that diversification methods offer notable improvements and enrich search results around the legal query space. In parallel, we demonstrated that that web search diversification techniques outperform other approaches, e.g., summarization-based, graph-based methods, in the context of legal diversification. Finally, we provide valuable insights for legislation stakeholders though diversification, as well as by offering balance boundaries between reinforcing relevant documents or information space sampling around legal queries.

A challenge we faced in this work was the lack of ground-truth. We hope for an increase of the size of truth-labeled dataset in the future, which would enable us to draw further conclusions about the diversification techniques. To this end, our complete dataset is publicly available in an open and editable format, along with ground-truth data, queries and relevance assessments.

In future work, we plan to further study the interaction of relevance and redundancy, in historical legal queries. While access to legislation generally retrieves the current legislation on a topic, point-in-time legislation systems address a different problem, namely that lawyers, judges and anyone else considering the legal implications of past events need to know what the legislation stated at some point in the past when a transaction or events occurred that have led to a dispute and perhaps to litigation [57].

Author Contributions

Marios Koniaris conceived of the idea, designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, drafted the initial manuscript and revised the manuscript. Ioannis Anagnostopoulos analyzed the results, helped to draft the initial manuscript and revised the final version. Yannis Vassiliou provided feedback and revised the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alces, K.A. Legal diversification. Columbia Law Rev. 2013, 113, 1977–2038. [Google Scholar]

- Koniaris, M.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Vassiliou, Y. Diversifying the Legal Order. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, Thessaloniki, Greece, 16–18 September 2016; pp. 499–509.

- Carbonell, J.; Goldstein, J. The use of MMR, diversity-based reranking for reordering documents and producing summaries. In Proceedings of the 21st annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, Melbourne, Australia, 24–28 August 1988; pp. 335–336.

- Gollapudi, S.; Sharma, A. An Axiomatic Approach for Result Diversification. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on World Wide Web, Madrid, Spain, 20–24 April 2009; pp. 381–390.

- Erkan, G.; Radev, D.R. LexRank: Graph-based lexical centrality as salience in text summarization. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2004, 22, 457–479. [Google Scholar]

- Otterbacher, J.; Erkan, G.; Radev, D.R. Biased LexRank: Passage retrieval using random walks with question-based priors. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, 45, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.; Guo, J.; Radev, D. Divrank: The interplay of prestige and diversity in information networks. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 July 2010; pp. 1009–1018.

- Zhu, X.; Goldberg, A.B.; Van Gael, J.; Andrzejewski, D. Improving Diversity in Ranking using Absorbing Random Walks. In Proceedings of the Human Language Technologies: The Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL-HLT), 2007, Rochester, NY, USA, 22–27 April 2007; pp. 97–104.

- Hand, D.J.; Mannila, H.; Smyth, P. Principles of Data Mining; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.M.; Raghavan, V.V. Vector space model of information retrieval: A reevaluation. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Cambridge, UK, 2–6 July 1984; pp. 167–185.

- Page, L.; Brin, S.; Motwani, R.; Winograd, T. The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web; Technical Report for Stanford InfoLab: Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Galgani, F.; Compton, P.; Hoffmann, A. Combining different summarization techniques for legal text. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Innovative Hybrid Approaches to the Processing of Textual Data, Avignon, France, 22 April 2012; pp. 115–123.

- Sanderson, M. Test Collection Based Evaluation of Information Retrieval Systems. Found. Trends® Inf. Retr. 2010, 4, 247–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radlinski, F.; Bennett, P.N.; Carterette, B.; Joachims, T. Redundancy, diversity and interdependent document relevance. In ACM SIGIR Forum; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 43, pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C.L.A.; Kolla, M.; Cormack, G.V.; Vechtomova, O.; Ashkan, A.; Büttcher, S.; MacKinnon, I. Novelty and diversity in information retrieval evaluation. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Singapore, 20–24 July 2008; pp. 659–666.

- Chapelle, O.; Metlzer, D.; Zhang, Y.; Grinspan, P. Expected reciprocal rank for graded relevance. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on Information and Knowledge Management—CIKM ’09, Hong Kong, China, 2–6 November 2009; pp. 621–630.

- Zhai, C.X.; Cohen, W.W.; Lafferty, J. Beyond independent relevance. In Proceedings of the 26th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, Toronto, ON, Canada, 28 July–1 August 2003; pp. 10–17.

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Nejdl, W.; Anand, A. History by Diversity: Helping Historians Search News Archives. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM on Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, Carrboro, NC, USA, 13–17 March 2016; pp. 183–192.

- Giannopoulos, G.; Koniaris, M.; Weber, I.; Jaimes, A.; Sellis, T. Algorithms and criteria for diversification of news article comments. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2015, 44, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Arvanitis, A.; Chrobak, M.; Hristidis, V. Multi-Query Diversification in Microblogging Posts. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Extending Database Technology (EDBT), Athens, Greece, 24–28 March 2014; pp. 133–144.

- Koniaris, M.; Giannopoulos, G.; Sellis, T.; Vasileiou, Y. Diversifying microblog posts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Information Systems Engineering, Thessaloniki, Greece, 12–14 October 2014; pp. 189–198.

- Song, K.; Tian, Y.; Gao, W.; Huang, T. Diversifying the image retrieval results. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2006; pp. 707–710.

- Ziegler, C.N.; McNee, S.M.; Konstan, J.A.; Lausen, G. Improving recommendation lists through topic diversification. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on World Wide Web, Chiba, Japan, 10–14 May 2005; pp. 22–32.

- Raman, K.; Shivaswamy, P.; Joachims, T. Online learning to diversify from implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Beijing, China, 12–16 August 2012; pp. 705–713.

- Makris, C.; Plegas, Y.; Stamatiou, Y.C.; Stavropoulos, E.C.; Tsakalidis, A.K. Reducing Redundant Information in Search Results Employing Approximation Algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database and Expert Systems Applications, Munich, Germany, 1–4 September 2014; pp. 240–247.

- Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Ji, L.; Xi, W.; Fan, W.; Chen, Z.; Ma, W.Y. Improving web search results using affinity graph. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Salvador, Brazil, 15–19 August 2005; pp. 504–511.

- Chen, H.; Karger, D.R. Less is more: probabilistic models for retrieving fewer relevant documents. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Seattle, WA, USA, 6–10 August 2006; pp. 429–436.

- Cronen-Townsend, S.; Croft, W.B. Quantifying Query Ambiguity. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Human Language Technology Research, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–27 March 2002; pp. 104–109.

- Santos, R.L.T.; Macdonald, C.; Ounis, I. Search Result Diversification. Found. Trends® Inf. Retr. 2015, 9, 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosou, M.; Pitoura, E. Search result diversification. ACM SIGMOD Rec. 2010, 39, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.L.; Macdonald, C.; Ounis, I. Exploiting query reformulations for web search result diversification. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, Hong Kong, China, 1–5 May 2010; pp. 881–890.

- Agrawal, R.; Gollapudi, S.; Halverson, A.; Ieong, S. Diversifying search results. In Proceedings of the second ACM international conference on web search and data mining, Barcelona, Spain, 9–11 February 2009; pp. 5–14.

- Hu, S.; Dou, Z.; Wang, X.; Sakai, T.; Wen, J.R. Search Result Diversification Based on Hierarchical Intents. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Melbourne, Australia, 19–23 October 2015; pp. 63–72.

- Langville, A.N.; Meyer, C.D. A survey of eigenvector methods for web information retrieval. SIAM Rev. 2005, 47, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, M. Innovative techniques for legal text retrieval. Artif. Intell. Law 2001, 9, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, C.; Francesconi, E.; Passerini, A.; Montemagni, S.; Soria, C. Automatic semantics extraction in law documents. In Proceedings of the 10th international conference on Artificial intelligence and law, Bologna, Italy, 6–11 June 2005.

- Mencia, E.L.; Fürnkranz, J. Efficient pairwise multilabel classification for large-scale problems in the legal domain. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Grabmair, M.; Ashley, K.D.; Chen, R.; Sureshkumar, P.; Wang, C.; Nyberg, E.; Walker, V.R. Introducing LUIMA: an experiment in legal conceptual retrieval of vaccine injury decisions using a UIMA type system and tools. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–12 June 2015; pp. 69–78.

- Saravanan, M.; Ravindran, B.; Raman, S. Improving legal information retrieval using an ontological framework. Artif. Intelli. Law 2009, 17, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweighofer, E.; Liebwald, D. Advanced lexical ontologies and hybrid knowledge based systems: First steps to a dynamic legal electronic commentary. Artif. Intell. Law 2007, 15, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagri, M.T.; Tiscornia, D. Metadata for content description in legal information. In Proceedings of the 14th International Workshop on Database and Expert Systems Applications, Prague, Czech Republic, 1–5 September 2003; pp. 745–749.

- Klein, M.C.; Van Steenbergen, W.; Uijttenbroek, E.M.; Lodder, A.R.; van Harmelen, F. Thesaurus-based Retrieval of Case Law. In Proceedings of the 2006 conference on Legal Knowledge and Information Systems: JURIX 2006: The Nineteenth Annual Conference, Paris, France, 8 December 2006; Volume 152, p. 61.

- Hoekstra, R.; Breuker, J.; di Bello, M.; Boer, A. The LKIF Core ontology of basic legal concepts. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Legal Ontologies and Artificial Intelligence Techniques (LOAIT 2007), Stanford, CA, USA, 4 June 2007.

- Farzindar, A.; Lapalme, G. Legal text summarization by exploration of the thematic structures and argumentative roles. In Text Summarization Branches Out Workshop Held in Conjunction with ACL; Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL): Barcelona, Spain, 25–26 July 2004; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Farzindar, A.; Lapalme, G. Letsum, an automatic legal text summarizing system. In Proceedings of the Legal Knowledge and Information Systems. JURIX 2004: The Seventeenth Annual Conference, Berlin, Germany, 8–10 December 2004; pp. 11–18.

- Moens, M.F. Summarizing court decisions. Inf. Process. Manag. 2007, 43, 1748–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktolga, E.; Ros, I.; Assogba, Y. Detecting outlier sections in us congressional legislation. In Proceedings of the 34th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval—SIGIR ’11, Beijing, China, 24–28 July 2011; pp. 235–244.

- Marx, S.M. Citation networks in the law. Jurimetr. J. 1970, 10, 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Van Opijnen, M. Citation Analysis and Beyond: In Search of Indicators Measuring Case Law Importance. In Proceedings of the Legal Knowledge and Information Systems-JURIX 2012: The Twenty-Fifth Annual Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 17–19 December 2012; pp. 95–104.

- Fowler, J.H.; Jeon, S. The Authority of Supreme Court precedent. Soc. Netw. 2008, 30, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.H.; Johnson, T.R.; Spriggs, J.F.; Jeon, S.; Wahlbeck, P.J. Network Analysis and the Law: Measuring the Legal Importance of Precedents at the U.S. Supreme Court. Political Anal. 2006, 15, 324–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgani, F.; Compton, P.; Hoffmann, A. Citation based summarisation of legal texts. In Proceedings of the PRICAI 2012: Trends in Artificial Intelligence, Kuching, Malaysia, 3–7 September 2012; pp. 40–52.

- Koniaris, M.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Vassiliou, Y. Network Analysis in the Legal Domain: A complex model for European Union legal sources. arXiv, 2015; arXiv:1501.05237. [Google Scholar]

- Lettieri, N.; Altamura, A.; Faggiano, A.; Malandrino, D. A computational approach for the experimental study of EU case law: analysis and implementation. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniaris, M.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Vassiliou, Y. Multi-dimension Diversification in Legal Information Retrieval. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Information Systems Engineering, Shanghai, China, 8–10 November 2016; pp. 174–189.

- Wittfoth, A.; Chung, P.; Greenleaf, G.; Mowbray, A. AustLII’s Point-in-Time Legislation System: A generic PiT system for presenting legislation. Available online: http://portsea.austlii.edu.au/pit/papers/PiT_background_2005.rtf (accessed on 25 January 2017).

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).