The Effect of Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Activities on Employee Deviance: The Mediating Role of Anomie

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Concepts and Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Views on CSR Activities

2.1.2. CSR and Employees’ Perceptions

2.1.3. Anomie

2.1.4. Employee Deviance

2.2. Hypotheses

2.2.1. Effect of Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Activities on Employee Deviance

2.2.2. Effect of Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Activities on Anomie

2.2.3. Effects of Anomie on Employee Deviance

2.2.4. Mediating Role of Anomie

2.3. Method

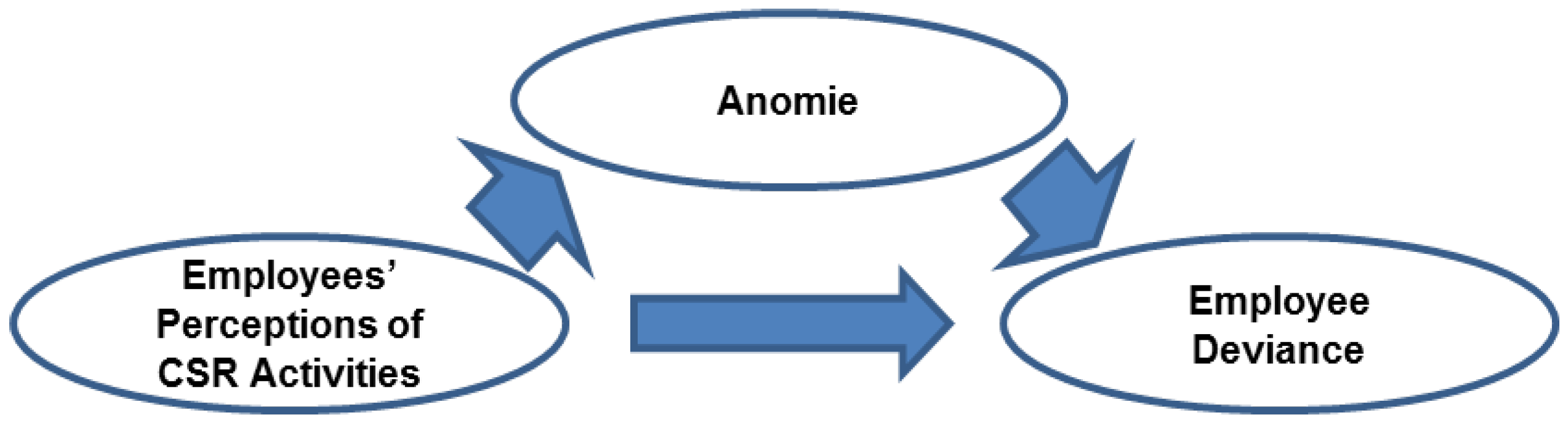

2.3.1. Research Model

2.3.2. Sampling and Analysis of Demographic Factors of Respondents

2.3.3. Measurement of Variables

Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Activities

Anomie

Employee Deviance

Control Variables

3. Results

3.1. Correlations

3.2. Regression Results 1 (H1)

3.3. Regression Results 2 (H2)

3.4. Regression Results 3 (H3)

3.5. Regression Results 4 (H4)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Questionnaire

CSR and Employees’ Perceptions

- Our company contributes to campaigns and projects that promote the well-being of the society.

- Our company implements special programs to minimize its negative impact on the natural environment.

- Our company participates in activities which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment.

- Our company targets sustainable growth which considers future generations.

- Our company makes investment to create a better life for future generations.

- Our company encourages its employees to participate in voluntarily activities.

- Our company supports nongovernmental organizations working in problematic areas.

- Our company supports employees who want to acquire additional education.

- Our company policies encourage the employees to develop their skill and careers.

- Our company implements flexible policies to provide a good work & life balance for its employees.

- The management of our company is primarily concerned with employees’ needs and wants.

- The managerial decisions related with the employees are usually fair.

- Our company provides full and accurate information about its products to its customers.

- Our company respects consumer rights beyond the legal requirements.

- Customer satisfaction is highly important for our company.

- Our company always pays its taxes on a regular and continuing basis.

- Our company complies with legal regulations completely and promptly.

Anomie

- In our firm, there is pressure to meet organizational objectives by any means possibles.*

- For the most part of work, there is no right or wrong way to achieve the firm’s goal.*

- At work it is considered okay to play dirty to win.

- The attitude in our firm is that sometimes it is necessary to lie to others in order to keep their trust.

- In our firm, the rules can be broken in order to achieve organizational goals.

- The prevailing attitude in our firm is that “nice guys finish last.”

- In our firm the feeling is that the ends justify the means.

- In our firm you have to be willing to break some rules if that is what it takes to get the job done.

Employee Deviance

- Exaggerated about your hours worked.

- Started negative rumors about your company.

- Gossiped about your coworkers.

- Covered up your mistakes.

- Competed with your coworkers in an unproductive way.

- Gossiped about your supervisor.

- Stayed out of sight to avoid work.

- Taken company equipment or merchandise.

- Blamed your coworkers for your mistakes.

- Intentionally worked slow.

Social Desirable Responding

- None of the managers at my firm feel dissatisfied with their jobs.

- At my company, all of the employees are outstanding performers.

- Employees at my company are always trustworthy.

References

- Palanski, M.E.; Yammarino, F.J. Integrity and leadership: Clearing the conceptual confusion. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.C.; Sharfman, M. Legitimacy, visibility and the antecedents of corporate social performance: An investigation of the instrumental perspective. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1558–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Tuzzolino, F.; Armandi, B.R. A need-hierarchy framework for assessing corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 6, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.K.; Song, H.J.; Lee, H.M.; Lee, S.; Bernhard, B.J. The impact of CSR on casino employees’ organizational trust, job satisfaction and customer orientation: An empirical examination of responsible gambling strategies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, L.; Cunningham, P. To thine own self be true? Employees’ judgments of the authenticity of their organization’s corporate social responsibility program. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, T.J. Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 887–910. [Google Scholar]

- Pastrana, N.A.; Sriramesh, K. Corporate social responsibility: Perceptions and practices among SMEs in Colombia. Public Relat. Rev. 2004, 40, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.D.; Johnson, J.L.; Cullen, J.B. Organizational change, normative control deinstitutionalization, and corruption. Bus. Ethics Q. 2009, 19, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.D.; Cullen, J.B.; Johnson, J.L.; Parboteeah, K.P. Deciding to bribe: A cross-level analysis of firm and home country influences on bribery activity. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1401–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.V. Creating and maintaining ethical work climates: Anomie in the workplace and implications for managing change. Bus. Ethics Q. 1993, 3, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B.; Parboteeah, K.P.; Hoegl, M. Cross-national differences in managers’ willingness to justify ethically suspect behaviors: A test of institutional anomie theory. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.V. Ethics and crime in business firms: Organizational culture and the impact of anomie. In The Legacy of Anomie Theory: Advances in Criminological Theory; Adler, F., Laufer, W.S., Eds.; Transaction Pub: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1995; Volume 6, pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski, S.S.; Kuczmarski, T.D. Values-Based Leadership; Prentice-Hall: Paramus, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique de Lara, Z.M.; Espinoza-Rodriguez, T.F. Organizational anomie as moderator of the relationship between an unfavorable attitudinal environment and citizenship behavior (OCB): An empirical study among university administration and services personnel. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toddington, S. Rationality, Social Action and Moral Judgement; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tsahuridu, E.E. The remoralisation of business. Presented at the International Conference of Reason in Practice and the Forum for European Philosophy: Developing Philosophy of Management, St Annes College, UK, 26–29 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Anomie and deviation: A conceptual framework for empirical studies. Br. J. Sociol. 1966, 17, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, N.S. Deviant managerial behavior: Costs, outcomes and prevention. J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, R.H. Ethics, discipline and human nature: A new look at management and deviance. Ind. Manag. 1989, 31, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Social structure and anomie. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1938, 3, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Measuring corporate citizenship in two countries: The case of the United States and France. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. Corporate sustainability: What is it and where does it come from? Ivey Bus. J. 2003, 67, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics training and businesspersons’ perceptions of organizational ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.I.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, C.M.; Gatewood, R.D.; Bill, J.B. Corporate image: Employee reactions and implications for managing corporate social performance. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Box, S. Ideology, Crime and Mystification; Tavistock: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.V. The dynamics of powerlessness: Explaining unethical conduct in business organizations. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–27 August 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.V. Ethical choice in the workplace: Situational and psychological determinants. In Doctoral Dissertation; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.V. Resisting the right stuff: Barriers to business ethics consultation. Academy of Management best paper proceedings. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–27 August 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, R. Organizational anomie and worker consent. Work Occup. 1999, 26, 292–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, N. Anomie and corporate deviance. Contemp. Crises 1990, 14, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D. Controlling Unlawful Organizational Behavior: Social Structure and Corporate Misconduct; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tsahuridu, E.E. Anomie and ethics at work. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. Executive values and the ethics of company politics: Some preliminary findings. J. Bus. Ethics 1989, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. Anomie, Anomia, and Social Interaction: Context of Deviant Behavior. In Anomia and Deviant Behavior; Clinard, M.B., Ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964; pp. 213–242. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, R.; Messner, S.F. Markets, Morality, and an Institutional Anomie Theory of Crime; Passas, N., Agnew, R., Eds.; The future of anomie theory 207–224; Northeastern University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L.; Martin, K.D.; Saini, A. Strategie culture and environmental dimensions as determinants of anomie in publicly-traded and privately-held firms. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 473–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, L. A cultural perspective on changing and developing organizational ethics. In Research in Organization Change and Development; Woodman, R., Passmore, W., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1990; Volume 4, pp. 195–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, E. Organisational crime: A theoretical perspective. In Studies in Symbolic Interaction; Denzin, N., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, UK, 1978; pp. 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Clinard, M.B. Corporate Ethics and Crime; Sage: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J.B.; Victor, B.; Stephens, C. An ethical weather report: Assessing the organizations ethical Climate. Organ. Dyn. 1989, 18, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.W.; Smith, B.D.; Grojean, M.W.; Ehrhart, M. An organizational climate regarding ethics: The outcome of leader values and the practices that reflect them. Leadersh. Q. 2001, 12, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- Trevino, L.K.; Weaver, G.R. Organizational justice and ethics program “Follow-Through”: Influences on employees’ harmful and helpful behavior. Bus. Ethics Q. 2001, 11, 651–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1985; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.A.; Ashforth, B.E. Loyal from day one: Biodata, organizational identification and turnover among newcomers. Per. Psychol. 1995, 48, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M. To be or not to be? Central questions in organizational identification. In Identity in Organizations; Whetten, D.A., Godfrey, P., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; van Schie, E.C.M. Foci and correlates of organisational identification. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.; Peccei, R. Organizational identification: Development and testing of a conceptually grounded measure. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickona, T. Moral Development and Behavior: Theory, Research and Social Issues; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H.C.; Hamilton, V.L. Crimes of Obedience: Toward a Social Psychology of Authority and Responsibility; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Theories of decision making in economics and behavioural science. In Decisions, Organisations and Society; Castles, F.G., Murray, D.J., Pollitt, C.J., Potter, D.C., Eds.; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK, 1976; pp. 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- MacIver, R.M. The Ramparts We Guard; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Srole, L. Social integration and certain corollaries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1956, 21, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, Y. The effects of organizational and ethical climates on misconduct at work. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, B.J.; Kyj, M.J. Economics and ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 1990, 9, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.S.; Jin, H.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Lim, J.C. Emerging predictors of organizational commitment and turnover intention in the case of Chinese employees: Perceived external prestige, ethical organizational climate and leader-member exchange (LMX) quality. Korean J. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2010, 12, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. A Theory and Measure of Ethical Climate in Organizations; Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy 9; JAI Press: Greenwich, UK, 1987; pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J. The organizational bases ethical work climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.K. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Riberio, N.; Chuha, M.P. Perceptions of organizational virtuousness and happiness as predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 93, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, S. A developmental test of Mertonian anomie theory. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1995, 32, 136–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Bennett, R.J. A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Loughlin, C.; Barling, J.; Nault, A. Self-reported counterproductive behaviors and organizational citizenship behaviors: Separate but related constructs. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2002, 10, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, K.C.; Bearden, W.O.; Tian, K. Development and validation of the agents’ socially desirable responding (ASDR) scale. Mark. Lett. 2009, 20, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Age | −0.194 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Employment period | −0.206 ** | 0.646 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Position | −0.228 ** | 0.469 ** | 0.386 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Business Area | −0.059 | 0.242 ** | 0.260 ** | −0.102 | 1 | |||||||||

| Firm age | −0.047 | 0.099 | 0.220 ** | 0.140 * | 0.021 | 1 | ||||||||

| CSR perceptions | −0.152 * | 0.059 | 0.118 | 0.044 | 0.204 ** | 0.193 ** | 1 | |||||||

| Society | −0.148 * | 0.012 | 0.110 | 0.027 | 0.136 * | 0.218 ** | 0.938 ** | 1 | ||||||

| Employee | −0.142 * | 0.060 | 0.050 | 0.021 | 0.202 ** | 0.133 * | 0.880 ** | 0.755 ** | 1 | |||||

| Customer | −0.078 | 0.111 | 0.149 * | 0.041 | 0.198 ** | 0.160 * | 0.849 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.648 ** | 1 | ||||

| Government | −0.136 * | 0.079 | 0.138 * | 0.110 | 0.230 ** | 0.099 | 0.668 ** | 0.508 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.690 ** | 1 | |||

| Anomie | 0.079 | −0.090 | −0.101 | 0.033 | −0.230 ** | −0.115 | −0.360 ** | −0.282 ** | −0.277 ** | −0.359 ** | −0.435 ** | 1 | ||

| Employee deviance | −0.035 | −0.102 | −0.074 | −0.015 | −0.234 ** | −0.077 | −0.205 ** | −0.156 * | −0.117 | −0.218 | −0.340 ** | 0.600 ** | 1 | |

| SDR | −0.075 | 0.049 | 0.100 | 0.022 | 0.127 * | −0.010 | 0.643 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.662 ** | 0.508 ** | 0.264 ** | −0.114 | −0.052 | 1 |

| Category | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | ||

| Control variable | (Constant) | 4.831 | 0.000 | 5.532 | 0.000 |

| Gender | −0.175 | −0.064 | −0.243 | −0.089 | |

| Age | −0.169 | −0.066 | −0.190 | −0.074 | |

| Employment period | 0.114 | 0.046 | 0.096 | 0.038 | |

| Position | −0.083 | −0.029 | −0.068 | −0.024 | |

| Business area | −0.742 | −0.232 | −0.632 | −0.198 ** | |

| Firm age | −0.184 | −0.075 | −0.057 | −0.023 | |

| SDR | −0.031 | −0.029 | 0.144 | 0.133 | |

| Independent variable | Employees’ perceptions of CSR activities | −0.327 | −0.259 ** | ||

| R square (▲ R square) | 0.068 | 0.103 | (0.035 **) | ||

| F | 2.515 * | 3.455 ** | |||

| Category | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | ||

| Control variable | (Constant) | 4.818 | 0.000 | 6.187 | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.189 | 0.061 | 0.057 | 0.018 | |

| Age | −0.134 | −0.046 | −0.175 | −0.061 | |

| Employment period | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.038 | −0.013 | |

| Position | 0.214 | 0.067 | 0.243 | 0.076 | |

| Business area | −0.706 | −0.196 | −0.492 | −0.136 | |

| Firm age | −0.316 | −0.113 | −0.068 | −0.024 | |

| SDR | −0.104 | −0.085 | 0.239 | 0.195 * | |

| Independent variable | Employees’ perceptions of CSR activities | −0.639 | −0.448 ** | ||

| R square (▲ R square) | 0.079 | 0.184 | (0.105 **) | ||

| F | 2.980 ** | 6.818 ** | |||

| Category | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | B | β | ||

| Control variable | (Constant) | 4.831 | 0.000 | 2.328 | 0.000 |

| Gender | −0.175 | −0.064 | −0.273 | −0.100 | |

| Age | −0.169 | −0.066 | −0.099 | −0.039 | |

| Employment period | 0.114 | 0.046 | 0.115 | 0.046 | |

| Position | −0.083 | −0.029 | −0.194 | −0.068 | |

| Business area | −0.742 | −0.232 ** | −0.375 | −0.117 * | |

| Firm age | −0.184 | −0.075 | −0.020 | −0.008 | |

| SDR | −0.031 | −0.029 | 0.023 | 0.021 | |

| Independent variable | Anomie | 0.520 | 0.586 ** | ||

| R square (▲ R square) | 0.068 | 0.384 | (0.317 **) | ||

| F | 2.515 | 18.864 | |||

| Category | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anomie | Employee Deviance | Employee Deviance | |||||

| B | Β | B | β | B | β | ||

| Control variable | (Constant) | 6.187 | 5.532 | 2.311 | |||

| Gender | 0.057 | 0.018 | −0.243 | −0.089 | −0.272 | −0.100 | |

| Age | −0.175 | −0.061 | −0.190 | −0.074 | −0.099 | −0.039 | |

| Employment period | −0.038 | −0.013 | 0.096 | 0.038 | 0.115 | 0.046 | |

| Position | 0.243 | 0.076 | −0.068 | −0.024 | −0.194 | −0.068 | |

| Business area | −0.492 | −0.136 | −0.632 | −0.198 | −0.376 * | −0.118 | |

| Firm age | −0.068 | −0.024 | −0.057 | −0.023 | −0.022 | −0.009 | |

| SDR | 0.239 | 0.195 | 0.144 | 0.133 | 0.020 | 0.18 | |

| Independent variable | Employees’ perceptions of CSR activities | −0.639 | −0.448 ** | −0.327 | −0.259 ** | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| Mediating variable | Anomie | 0.521 | 0.587 ** | ||||

| R square (▲ R square) | 0.184 | 0.103 | 0.384 | ||||

| F | 6.818 ** | 3.455 ** | 16.699 ** | ||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, Y.H.; Myung, J.K.; Kim, J.D. The Effect of Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Activities on Employee Deviance: The Mediating Role of Anomie. Sustainability 2018, 10, 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030601

Choi YH, Myung JK, Kim JD. The Effect of Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Activities on Employee Deviance: The Mediating Role of Anomie. Sustainability. 2018; 10(3):601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030601

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Yun Hyeok, Jae Kyu Myung, and Jong Dae Kim. 2018. "The Effect of Employees’ Perceptions of CSR Activities on Employee Deviance: The Mediating Role of Anomie" Sustainability 10, no. 3: 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030601