1. Introduction

Scholarly writing on the multi-dimensional influences of tourism-related commodification and World Heritage nomination on local communities has increased in recent years. Research has related the influences of tourism development primarily to the commodification of traditional culture’s physical and ritual aspects through the interaction between tourists and local actors [

1,

2]. When conventional rituals are changed into commercial performances, the historical value and the ethnic identity of the rituals also change, if gradually. From a variety of scholarly perspectives, these studies have revealed the ongoing power of cultural colonialism and hierarchy between tourists and local residents [

3,

4].

Heritage scholars have also explored the influences of heritage authorization on local communities, particularly the impacts of World Heritage authorization on the national and local levels [

5]. The currently accepted concept of “heritage” originated in the nineteenth century in the context of modernity in Europe, particularly in Britain, France, and Germany [

6,

7]. This concept of heritage, which is related to European colonial expansion, facilitates the idea that European culture is and was more advanced than others. This was often depicted in the developed of new institutions of taxonomy and pedagogy, such as the museum [

8]. With the emergence of the modern nation state, this concept of heritage also strengthened national identity [

9]. Among the international conventions and charters for the preservation of cultural heritage that have been created, the most influential and successful has been the Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage (CCPWCNH) developed by UNESCO. This convention was first adopted in 1972, and the first Operational Guidelines for Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (OGIWHC) were passed in 1977. However, the adoption of the CCPWCNH was criticized for its hegemony in imposing European ideas on heritage in non-European countries in both policy and practice. The critical point is that the CCPWCNH was originated and is embedded in the European context, and that its operation has often overlooked the value of culture and cultural heritage in non-European countries, especially those forms that do not accord with the authorized version.

Such criticism is also reflected in the historical understanding of authenticity in China. For example, Chinese people historically were not concerned with the material authenticity of traditional architecture or the historical and cultural value embedded in the architecture [

10] (p. 41). For instance, the value of a copy of a palace or other built space would not be regarded as less “authentic” or “valuable” than the original. In fact, if the “copy” buildings had been commissioned by an emperor or other authority figure, such commissioning would actually enhance the value of the original [

11] (p. 22), while the European heritage principle would ascribe little authenticity value to such a reconstructed building. Nonetheless, in the contemporary period, the CCPWCNH creates authenticity and integrity criteria for the inscription of World Heritage. In order to meet the criteria, many local governments have launched authentication projects, including the restoration of built heritage and removing/purifying of unharmonious environments under the guidance of heritage experts [

12]. Both criteria can lead to controversial consequences. For example, the local government forcefully displaced about 2000 local residents when the Shaolin monastery was inscribed as part of a World Heritage site [

13].

Here, I am mobilizing Laurajane Smith’s notion of an Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD). AHD refers to “a Western discourse about heritage” that now dominates the understanding of heritage around the world [

6] (p. 4). A hegemonic heritage discourse such as AHD is “reliant on the power/knowledge claims of technical and aesthetic experts, and institutionalized in state cultural agencies and amenity societies” [

6] (p. 11). Heritage authorization is a cultural process that excludes certain actors from engaging in heritage-related efforts [

6] (p. 44). If such is the case, which actors will be excluded, and how does this happen in heritage-based tourist destinations in China? Considering the controversial influences of tourism-related commodification on local culture, what is the interaction between heritage authorization and tourism-related commodification? How does this interaction influence the transformative process of heritage-based tourist destination? In particular, which social actors are excluded in this process and how? These are some of the questions to be examined further below.

In order to examine these questions, I refer to Anthony Giddens’ theories concerning modernity. Giddens’ conceptualization of time–space distanciation, disembedding, and reflexivity are applied, to clarify how the heritage system and the tourism system interact to drive the transformative process of heritage-based tourist destinations. Time–space distanciation and the disembedding institution help to clarify the process of globalization, in that “modernity is inherently globalizing” [

14] (p. 63). Reflexivity refers more to local appropriation in this regard. The institution of CCPWCNH and other international agreements on heritage influence China’s heritage policies significantly, and in so doing reveal the dominant place of Western principles of preserving cultural heritage in China’s practice of heritage authorization. The expert system, as part of disembedding mechanics, facilitates both heritage authorization and tourism-related commodification.

The two systems interact to create a traditional-style culture, which is similar to the notion of an “invented tradition” [

9]. Such invention of tradition is related to the political aspect of the nation-state, while the traditional-style culture is created by both the heritage system and the tourism system. The traditional-style culture also differs from traditional culture, which is embedded in premodern societies, while traditional-style culture refers to cultural forms that are purposefully reconstructed to serve contemporary political and/or economic needs. In traditional-style culture, only the forms are traditional, while their nature is modern, and their production is embedded in the modern system. It is argued here that traditional-style culture is the product of the interaction between heritage authorization and tourism development.

This study examines how, in China, the interaction between heritage authorization and tourism-related commodification shapes the transformative process of heritage-based tourist destinations. The study further examines how local social actors are excluded in this process. The paper firstly introduces the qualitative approach, and case study and data collection methodology. Secondly, in linking Giddens’ modernity theory to the transformative process of heritage-based tourist destinations in China, a theoretical framework will be established to better understand heritage authorization and tourism development. Thirdly, the case study of authentication and tourism-related commodification in the ACP is presented and analyzed using local resident responses. Finally, in discussing the interaction between heritage authorization and tourism development, the conclusion is forwarded that during this process local residents have been disempowered culturally, spatially, and financially.

2. Methodological Considerations

In light of the research questions presented above, concerning the transmission of heritage knowledge and practice from Western countries and its influence on the social relations of actors in heritage-based tourist destinations in China, this study uses a combination of constructivism and qualitative data collection and analysis. This study focuses on the globalization of heritage discourse and its impact on local actors, the problem of structure and agency, and the concept of heritage in specific time–place settings (that is, locally constructed realities). Constructivism, which holds a relativist ontology that views the world as being constructed of multiple and dynamic realities [

15], notes that different actors have different understandings of heritage, and that they translate this understanding into a corresponding social reality. Of course, as shall also be examined below, the views of some actors are more powerful and influential than those of others.

A qualitative approach with a case study is consistent with the adoption of a constructivist paradigm [

16]. Four kinds of data are used: documentation, archival records, participant observation, and interviews. The fieldwork was conducted in Pingyao in February 2015 and April 2016, and included observation of local residents while living in a traditional inn operated by a local resident, and participation in activities like making dumplings, local foods, and local souvenirs. Observing local residents’ everyday behaviors and spatial–cultural preferences helped to reveal their attitudes toward traditional and “invented” festivals. Such observation provided the opportunity to become immersed in the community and to produce personal reflections on the themes under investigation. These personal experiences make the strange familiar and the familiar strange [

17].

In-depth interviews provide significant materials for this study. In-depth interviews were conducted with thirty-one local residents (

Table 1), two experts, and two local officials. All interviews were conducted in Mandarin, with some use of the local Pingyao dialect. Interviews were recorded with permission, and later transcribed for analysis and quotation. Interviews with local residents lasted one to two hours, and covered such topics as how they think about the influences of tourism development on their daily lives, and how they feel about the influences of World Heritage authorization on their daily lives. Twenty-three interviewees were local residents of the ACP, and eight lived outside the ACP, but still operated tourism-related businesses inside the ACP. In addition to these formal interviews, I took every opportunity to approach other local residents to address their attitudes and feelings about heritage authorization processes and local tourism development.

Experts and local officials are influential agents in heritage authorization and tourism development in Pingyao, and their thoughts and views on heritage and tourism development have been reflected in published articles and government reports. In addition to collecting some official documents and archival records, I conducted in-depth interviews with one heritage expert, one tourism expert, and two local officials, all of whom were familiar with the heritage authorization process and tourism development in Pingyao. Interview data from experts and government officials were corroborated by their arguments presented in articles and various documents.

3. Theoretical Framework: Understanding Heritage, Tourism-Related Commodification and Authentication in Heritage-Based Tourist Destinations in China

The modern concept of heritage was transmitted from Europe to China in the early twentieth century. Chinese people historically neither regarded traditional architecture as valuable nor did they care about the material authenticity of the historical or cultural value embedded in the architecture. Liang Qichao (1873–1929), described as “the mind of modern China,” argued for the renewal of Confucianism in China through the study of Western knowledge [

18]. When Liang Qichao visited North America and Europe, he recognized that Westminster Abbey and the House of Parliament were living reflections of the entire British nation, and that Gothic cathedrals represented the embodiment of a “national spirit” that had been inherited from various periods in history [

19]. His son, Liang Sicheng (1901–1972), having studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, introduced Western knowledge about built heritage to China, and explored restoration methods for Chinese traditional architecture with other Chinese scholars who had similar backgrounds [

20,

21].

Because of the cultural background and timber-framed nature of Chinese traditional architecture, the term “authenticity (

yuanzhenxing or

zhenshixing)” diversified the understanding and principles of the conservation practice of built heritage in China [

22]. Liang Sicheng regarded the restoration principle of Chinese architecture as “restoring the old to appear as old (

xiujiurujiu),” an approach to restoration that advocates returning ancient buildings to their original form by removing later additions [

23]. This principle has the same conservation philosophy as the French approach to historic restoration, which emphasizes keeping the traditional architecture to a certain style by changing or replacing some parts of the traditional architecture. However, this approach is condemned by the English approach, as it does not respect historic authenticity, since it advocates restoration to the original form without the later contributions [

24] (p. 358) [

25]. Furthermore, Liang’s restoration philosophy differs from the CCPWCHN’s authenticity criteria and those of other international documents that advocate minimal intervention for built heritage, and consider historical restorations done in Liang’s way to damage the historical authenticity of the built heritage [

22].

However, Liang’s influence on the restoration of traditional architecture remains significant in contemporary China since he shaped generations of architects and educators who have contributed to preserving/restoring built heritage in both policy and practice in China. For example, the Law on the Protection of Cultural Heritage in PRC (LPCHPRC) requires that “in the repairing, maintaining, and removing of immovable cultural relics, the principle of keeping the cultural relics in their original state shall be adhered to” (Article 21), which reflects Liang’s stylistic restoration principle. However, the term “original state” is controversial and ambiguous because it does not explain whether “original state” refers to the earliest state, the state before it was last damaged, or the state in its most splendid era. In this regard, heritage experts have interpreted spaces to identify the “original state” and, thus, authenticity. Liang and his followers constitute the heritage expert group in China, who interpret international heritage conventions to Chinese practices and, thus, have legitimized power in the heritage field.

The highly controversial notions of authenticity in heritage conservation in China leaves space for local governments to negotiate legitimate authentication projects tactically for World Heritage authorization and tourism-related commodification. Numerous studies have revealed that host countries and the private sector regard the World Heritage listings as significant drivers for attracting tourists [

26]. In China, a World Heritage inscription has found synergy with tourism development as an impetus to local economies [

22,

27,

28,

29], creating a tourism-driven heritage authorization model. Local residents, who are perhaps the owners of heritage, but less influential stakeholders because of their economic disadvantage, are consequently disempowered. For example, in the World Heritage site of Hongcun Village, large external capital that has the support of local governments dominates tourism businesses, but local residents benefit little from tourism-related commodification [

30]. Therefore, although heritage authorization does not necessarily lead to commercializing heritage, its connection to tourism development usually finds synergy with the inflow of external capital and leads to local residents’ disempowerment [

31] (pp. 31, 130).

Local residents are also disempowered spatially when they must relocate outside the heritage site in the name of authenticating and protecting heritage. In the World Heritage authorization of Wutai Shan, a Taoist religious area in China, local residents were displaced [

12,

32]. Similarly, local residents were relocated outside of their community near Shaolin temple before it was listed as part of World Heritage [

13]. About 90 percent of local residents in the World Heritage site Lijiang Old Town were relocated because of an overflow of tourists [

33]. The case of China’s Hainan Province also included the tourism-caused displacement of local residents [

34]. Such relocation leads to the detachment of communities and destroys the integrity of their culture. This is particularly problematic given that local residents’ attitudes influence the sustainable development of heritage sites [

35]. All of these examples demonstrate that local residents who have been disempowered economically, culturally, and spatially under the tourism-driven heritage authorization process.

Furthermore, the tourism-driven World Heritage authorization process in China reflects the globalization and localization of Chinese heritage. Giddens’ modernity theories, including time–space distanciation, disembedding (and re-embedding), and reflexivity, are applied to establish a theoretical framework to explain the tourism-driven heritage authorization in China. Later, these insights will be applied to the Pingyao case. Time–space distanciation means space is separated from place in that social activities are not determined only by localized factors, but also by geographically distant factors, while disembedding mechanics refer to “the ‘lifting out’ of social relations from local contexts of interaction and their restructuring across indefinite spans of time–space” [

14] (p. 21). The CCPWCNH, issued by UNESCO and originating in Europe, has itself shaped the authorized cultural heritage systems in China. In particular, it provides detailed guidelines related to preserving methods and standards, regardless of the diversity of local contexts. This international standard has the potential to alter social relationships that are embedded in original time–space contexts, where local people could independently manage cultural preservation.

Just as Giddens’ analysis of “expert system” and “experts” in disembedding mechanics [

14], heritage experts, who link the CCPWCNH to local practice, have been qualified to determine the restored style of built heritage. Although the CCPWCNH has been criticized for giving heritage experts too much power in evaluating heritage in a hegemonic way [

6], local governments in China have to depend on their professional expertise to meet the CCPWCNH’s criteria for inscription. The Chinese way of restoring built heritage is a negotiated approach to authenticity, so heritage experts’ restoration of built heritage is a way of reconstructing traditional culture. However, their views on reconstruction are authorized as part of heritage, while local residents’ reconstruction is usually viewed as false or unimportant. The heritage discourse suggests that heritage is more valuable to pseudo-reconstruction, reflecting the unequal power between heritage experts and local residents.

Giddens’ reflexivity refers to an “institutional reflexivity” in which agents influence social structure, and which involves the “reflexive monitoring of action” [

14] (p. 36). A low level of social reflexivity results in an individual’s being shaped largely by structure, while a high level of social reflexivity is defined by an individual’s shaping such things as his or her own social norms, personal tastes, and political orientation. In reconstructing traditional-style culture related to built heritage, Chinese heritage experts have revealed an institutional reflexivity by applying international standards to local contexts [

22], while local residents, who have no professional knowledge of heritage, but have their own understanding of authenticity and heritage, usually demonstrate a lower level of reflexivity [

36].

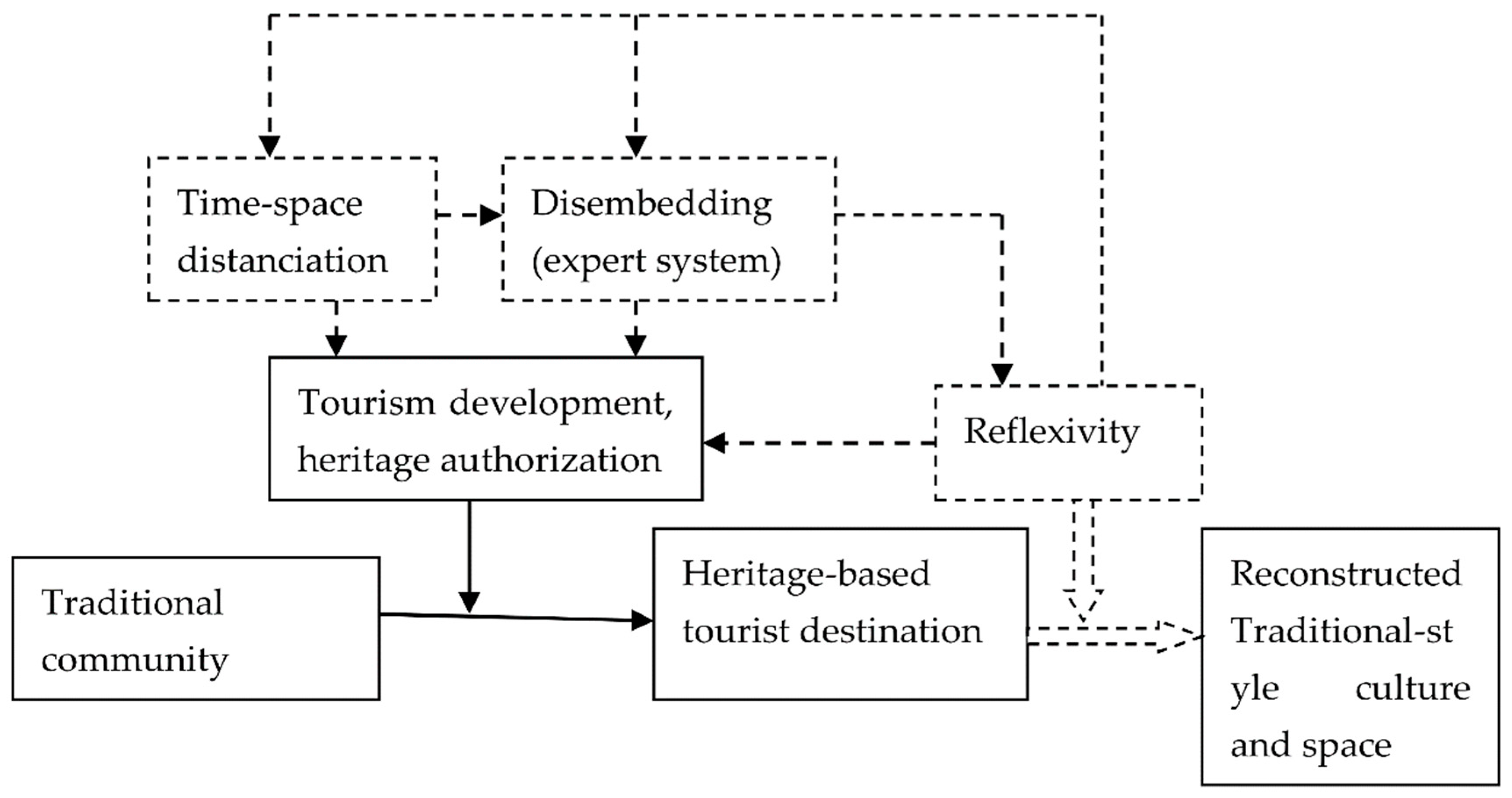

Based on this linking of Giddens’ modernity theory to the transformative process in heritage-related tourism sites in China, a theoretical framework is established as shown in

Figure 1.

4. Historical Background (Pre-1949 and 1949 to 1978)

In 1997, the ACP was inscribed as a World Cultural Heritage site as

“an outstanding example of a Han Chinese city of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (14th–20th centuries) that has retained all its features to an exceptional degree and in doing so provides a remarkably complete picture of cultural, social, economic, and religious development during one of the most seminal periods of Chinese history.”

The ACP was first constructed by Yin Jifu for Emperor Xuan in the Western Zhou dynasty (827–782 BC) to defend against a minority group, the Xianyun. Because of its special location, the ancient wall of the ACP fulfilled a military function, and was reconstructed and strengthened many times. The city was formed within the ancient walls. This section explores the historical background of the ACP, and its traditional and enclosed features before it was listed as a World Heritage site.

The ACP was first constructed for military defense. Its economy changed from a limited one, before the Ming dynasty, to a larger one in the late Qing dynasty. The period of the Qing dynasty, from 1644 to 1911, saw the emergence of prosperous commodities, such as dyeing and bank drafts in Pingyao [

37] (p. 11). Specifically, Pingyao was the financial center of China from 1823 to the early twentieth century. The prosperity of commerce in Pingyao facilitated the construction of the ACP and many of the public and private traditional buildings within it. The public and private traditional buildings and the layout of the ACP were constructed strictly in line with Chinese traditional culture, mainly Confucianism and Taoism. As the buildings and settlements were the visible expression of generally shared and accepted values [

38] (p. 47), the values originated by Chinese traditional culture were projected onto the physical spaces of the ACP, and the spaces injected the people with those values.

Confucian thought, which once underpinned behavioral rules, was projected onto the built environment in China [

39]. The construction of the ACP was influenced by Confucian principles in terms of subordinated social order, and by Taoism in terms of unity of heaven, earth, and people in the cosmos [

40]. The layout of the ACP reflects Taoist thought in a Yin–Yang system. An understanding of the cosmic principles through the five elements of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water is used to express the essence of the Yin–Yang system. As

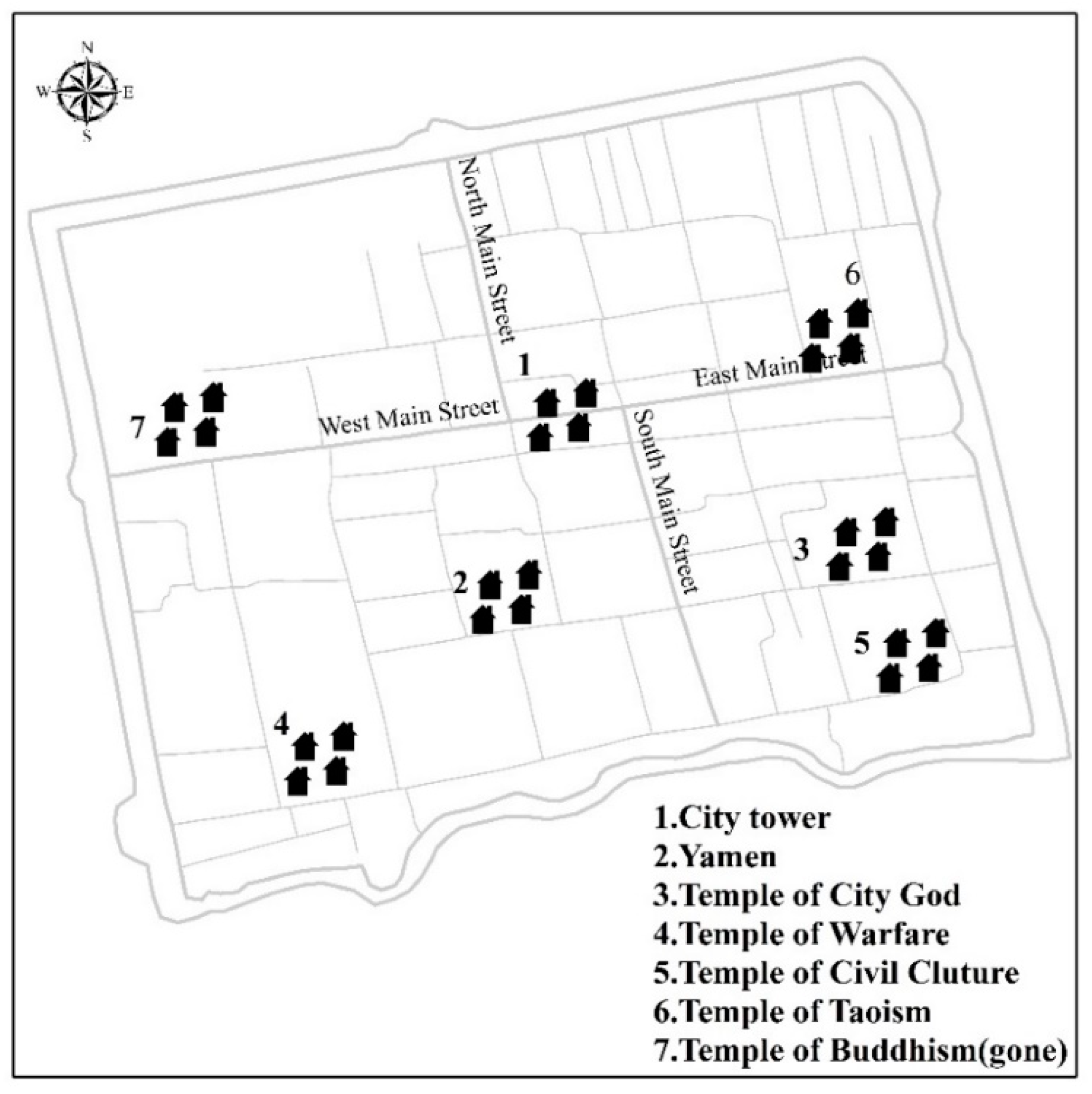

Figure 2 [

41] shows, the cities are viewed as a mini-cosmos, with the five elements representing the four cardinal points and the center (east for spring, wood, and dark blue; west for autumn, metal, and white; north for winter, water, black; south for summer, fire, and red; and center for late summer, earth, and yellow). The Confucius temple is located in the east, representing sunrise, spring, green, and wood, while the Warfare temple is situated in the west, symbolizing the sunset, autumn, white, and metal.

In traditional times, Pingyao’s people were embedded in the ACP, into which Chinese traditional culture was projected. On one hand, Confucianism has had a powerful influence on Chinese behavior and social structure [

42] (p. 35), providing guidance on the ethical principles of social and political life. On the other hand, the layout of the ACP and its traditional buildings were designed in line with both Confucianism and Taoism. Taoism and Buddhism both add psychological and spiritual dimensions [

43] (p. 224). It is clear that Pingyao’s people were embedded in the enclosed and integral spaces of the ACP, which existed only for locals, without external intervention from changing economic conditions. In other words, the spatial arrangement into which Chinese traditional culture was projected was also injected into Pingyao’s people.

The period from 1949 to 1978 witnessed rigid opposition to traditional culture under Mao’s radical socialism. In particular, the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) revealed the extreme and totalistic anti-traditionalism under the ideology of “Attack the Four Olds” of customs, culture, habits, and ideas [

44]. Although the cultural value in built heritage was interpreted in line with Mao’s dictum to “use the past to serve the present”, where history was interpreted as a tool to serve socialist ideology [

10] (p. 15), most traditional buildings in Pingyao were regarded as physical objects without cultural meaning, and turned into socialist infrastructure without being fully demolished under materialism. The layout and the pattern of streets were kept, while some traditional public buildings, such as the temples, were used as public socialist infrastructure with socialist functions.

Table 2 lists the detailed changes in the functions of traditional buildings in Mao’s era.

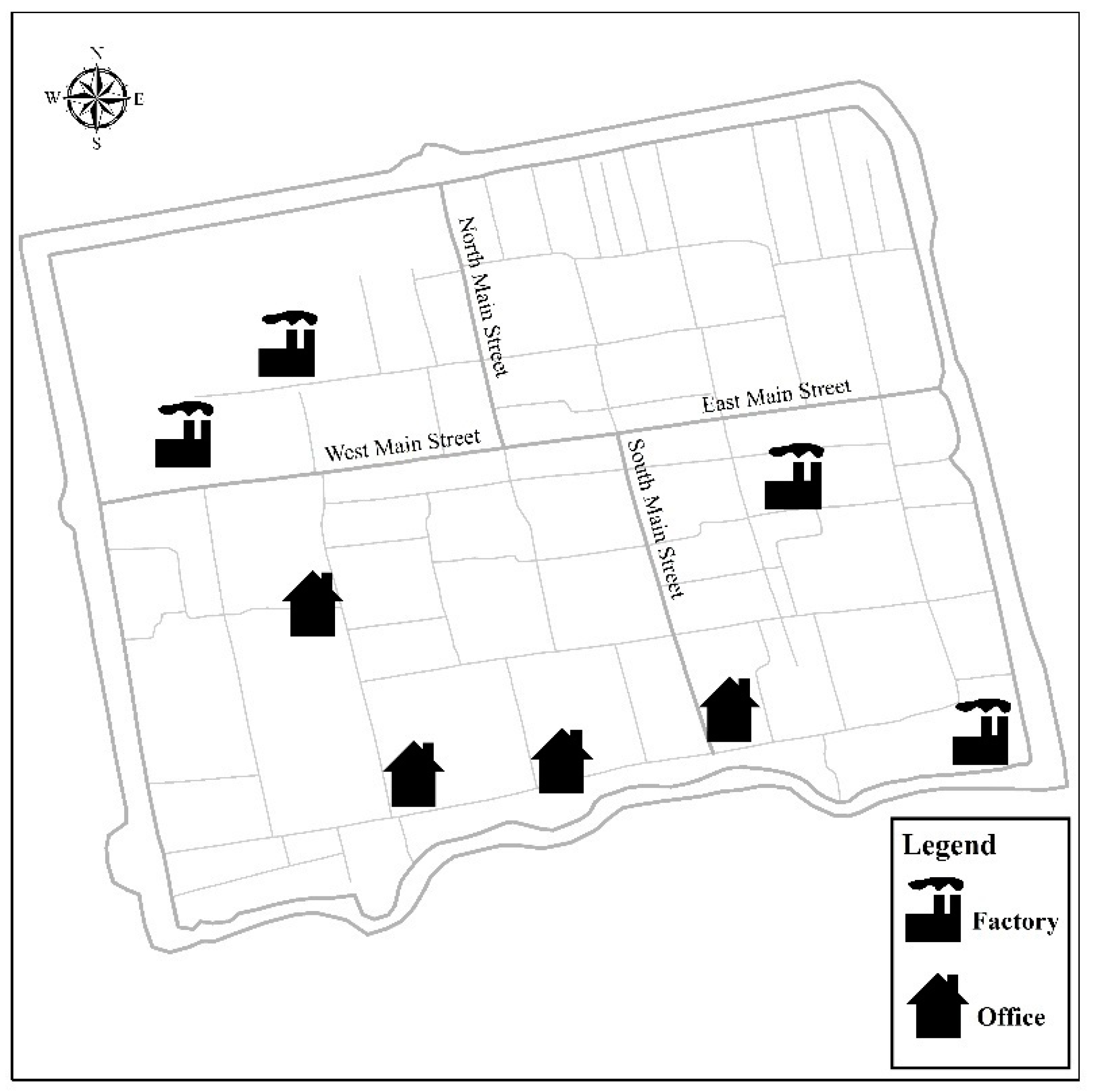

Other than changing traditional public buildings into socialist infrastructure, two new types of buildings were constructed in Mao’s era: modern buildings (the Chinese People’s Bank, the People’s courthouse, and the Pingyao Hotel, auditorium, post office, jail, and local police station) that represented the new socialist culture, and some small socialist factories (a cotton textile-spinning and -weaving mill, and an agricultural machinery plant) [

41] (p. 109). These newly built factories were arranged in the fringes of the ACP, usually at the northwest corner or in the east or southeast areas, where there was more vacant land and a low density of population, as indicated in

Figure 3 [

41]. These new constructions were all built of cement, bricks, and other modern materials in modern forms that differed significantly from the traditional buildings.

The ACP still existed for locals, whose actions and behaviors were influenced by Mao’s radical socialism in this enclosed socialist space. For example, when asked about life in Mao’s era, one interviewee said, “At that time we lived a very poor life, but we were inspired, happily believing that Chairman Mao would guide us to a socialist society in which everything is well and everyone is happy” (Interviewee, aged 68). However, the ACP’s physical settings demonstrated both traditional style and modern style. Although some buildings kept their style traditional in appearance, the projected traditional Chinese culture could not be injected into local people, since they were infused with socialist ideology. Culturally, these public traditional buildings were changed into socialist spaces. By contrast, the newly constructed buildings showed a modern style, with consistency between the projection and injection of socialism. As a result, the ACP became a socialist community, but still an enclosed space, with traditional-style and modern-style buildings.

5. Authentication and Tourism-Related Commodification of ACP

The Dengist era of “reform and openness” began in 1978. Deng’s model was called pragmatic and evolutionary socialism, or “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” in China or “Dengism,” and, after 1992, focused on a “socialist market economy” [

45] (p. 27). China’s socialist market economy was based on the political design of “federalism, Chinese style,” characterized by the development of fiscal decentralization with political durability [

46]. This decentralization depended only on the political relationships between levels of government [

46]. In this circumstance, local governments are expected to find effective ways to develop their local economies. Tourism is the way Pingyao’s government has identified to develop the local economy, through the use of the area’s heritage. This section focuses on how the interaction between World Heritage authorization and tourism-related commodification has shaped the processes of the ACP’s authentication in terms of its spatial, economic, and social aspects. This process is explored in order to explain the formation of the power structure in which social agents and actors engaged in reconstructing traditional-style culture.

5.1. Authentication: The Path to Authorized Authenticity

Heritage experts contributed significantly to the World Heritage listing of the ACP in 1997. Located in the remote western area, Pingyao could not get sufficient support from the central government to promote its economy when other local governments dismantled their traditional buildings in favor of urban modernization in the early 1980s. Ruan Yisan, a lecturer from Tongji University, tried to prevent the destruction of traditional buildings in the ACP when he found the Pingyao government had been dismantling about thirty buildings from the Ming dynasty, and one hundred buildings from the Qing dynasty, on a 180-meter stretch of road [

47] (p. 20). Ruan then made a master plan for Pingyao and posted it to the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MHURD) and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH). His idea of “Conserving the Ancient City Integrally, Dividing the New and the Ancient Completely, Improving the Internal Environment, and Developing Tourism Industry” was supported by administrators like Zheng Xiaoxie and Luo Zhewen [

48] (p. 14) [

49] (p. 11).

Ruan’s idea for Pingyao was similar to what Liang Sicheng had suggested for Beijing in 1958. Liang’s thoughts did not convince the CPC during the period from 1949 to 1978, but his students and followers were strong supporters. In fact, Zheng and Luo were followers of Liang when both undertook influential positions in administrative systems. Later, they visited the ACP, and SACH allocated RMB 80,000 to restore ACP’s ancient walls [

47] (p. 25). Because of Zheng’s and Luo’s influential positions, the Shanxi and Pingyao governments trusted the plan to conserve the ACP and quickly approved the Master Plan of Pingyao. Thus, the ACP was kept intact and listed as one of the second National Historical and Cultural Cities (NHCC) during the 1980s, and the Pingyao government received funding from the central government to conserve the ACP in the 1980s [

47] (p. 25). Clearly, these heritage experts with power and specialized knowledge greatly influenced Pingyao’s local development.

The fame of the NHCC attracted increasing numbers of tourists to the ACP, from 60,000 in 1988 to 167,000 in 1991 [

50], which led the local government to make an effort to inscribe the ACP as a World Heritage site to enhance tourism. In 1995, the Pingyao government officially confirmed the strategy of future development as “Using tourism to drive the economic prosperity of Pingyao” (

lvyouxingxian) [

51] (p. 809). In the 1990s, the Pingyao government invited heritage experts to visit the ACP in pursuit of the World Heritage inscription. For example, the Pingyao government sponsored the annual conference of the NHCC in the ACP in 1994. Heritage experts from the Ministry of Construction, SACH, and universities attended the NHCC conference and, with their support, the Pingyao government began to prepare for World Heritage inscription.

These external heritage experts contributed to inscribing ACP as a World Heritage site by linking the international conventions of CCPWCNH to local practice. They helped to plan the ACP in line with CCPWCNH criteria, and drafted the application for World Heritage authorization. Such knowledge and expertise are difficult for local actors to grasp. At their suggestion, the physical remains of Mao’s era were removed, and many traditional buildings that had been changed into socialist public infrastructure in Mao’s era, such as temples that became schools, were changed back physically into pre-Mao-era traditional spaces.

The authentication projects consisted of two parts: the relocation of public infrastructure to outside the ACP, and the official reconstruction of physically traditional-style spaces to show traditional features. I use “Relocation Project” and “Reconstruction Project” to refer to these two authentication projects, respectively. In regard to the Relocation Project, seventy-four government-related organizations, such as hospitals, schools, a sports center, and theaters, were relocated outside the ACP [

52]. Seven government-owned factories that were established in Mao’s era were also relocated outside the ACP to reduce air pollution. These public infrastructure buildings and government-owned factories provided living facilities and jobs for local residents at that time, but the local government relocated them in spite of their contributions to local development in Mao’s era. These contributions were part of these buildings’ historical contributions, and removing these contributions did not respect the real history of the built heritage. The other authentication project, Reconstruction Project, extended the disrespect for the area’s real history.

The Reconstruction Project consisted of three parts. First, South Street, known as the “Chinese Wall Street” in the late Qing dynasty, was packaged as the Ancient Street of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (Mingqingyitiaojie) to show the physically traditional features of the ACP. Most courtyards along South Street, which had been merchants’ houses before 1949 and were then transferred to local governments as public spaces in Mao’s era, were reconstructed into stores, inns, and restaurants as tourist facilities with a traditional-style appearance. Second, some disharmonious buildings and scenes, usually constructed between 1949 and 1978, were reconstructed with a Qing-style traditional appearance. For example, temples like the Confucian and City-God temples, which were used as schools in Mao’s era, were restored/reconstructed as temples in the traditional style. Third, power lines and other wires, viewed as messy and modern, were removed or placed underground, and the traditional features were reconstructed. These three parts targeted the reconstructing of aesthetically traditional-style buildings and scenes in the ACP.

The Relocation and Reconstruction authentication projects demonstrate the path to authorized authenticity that is institutionalized in the inscription of World Heritage. However, the authenticity of this type of restored heritage has been challenged, as removing the physical remains of certain eras has generated controversy for not respecting historical authenticity. The authenticity criteria in the 1977 version of the OGIWHC states

“the property should meet the test of authenticity in design, materials, workmanship and setting; authenticity does not limit consideration to original form and structure but includes all subsequent modifications and additions, over the course of time, which in themselves possess artistic or historical value.”

The 1980 and subsequent versions of the OGIWHC state that “Reconstruction is acceptable only on the basis of complete and detailed documentation and to no extent on conjecture” (2013 version OGIWHC, Article 86). However, interviews with two local residents, one heritage expert, and one local official, revealed that the reconstruction in the ACP was mainly in line with elderly people’s memories, that some documents about these structures had been destroyed in the Cultural Revolution, and some buildings had no detailed documents. Although the authenticity criteria of CCPWCNH is negotiated in the local context, heritage experts’ interpretations of the criteria in the local practice of official reconstructions/restorations strengthen the authenticity claims of these built heritages.

5.2. Local Residents’ Response

Inspired by the local government’s promotion and planning, local residents showed their support and understanding that the heritage authorization and expected tourism would bring more job opportunities [

53]. Nonetheless, the Relocation Project was inconvenient for them. As one interviewee said, “It was very inconvenient to live in the ACP after the hospital and schools moved out, because I have to send my child to school far away in the morning and receive him back in the afternoon”. However, they did not oppose or prevent the Relocation Project for two reasons: First, the local residents do not participate in policy-making or local planning processes in most areas in China [

30,

34], so they did not expect to influence local policy-making for the authentication projects. Second, the relocated public infrastructure belonged to government-owned or government-operated organizations. However, with a massive influx of tourists and resulting congestion and tourist-orientated development, they soon found themselves in a disadvantaged situation when the ACP became a popular heritage-based tourist site.

After the ACP was listed in 1997, it attracted many tourists, coinciding as it did with the rise of domestic tourism in China. Tourist arrivals in the ACP increased from 142,000 in 1997 to 420,000 in 1999 [

54] and to 1,563,700 in 2016, with ticket revenue from visitors increasing from RMB 1.04 million in 1997 to RMB 133.95 million in 2016 [

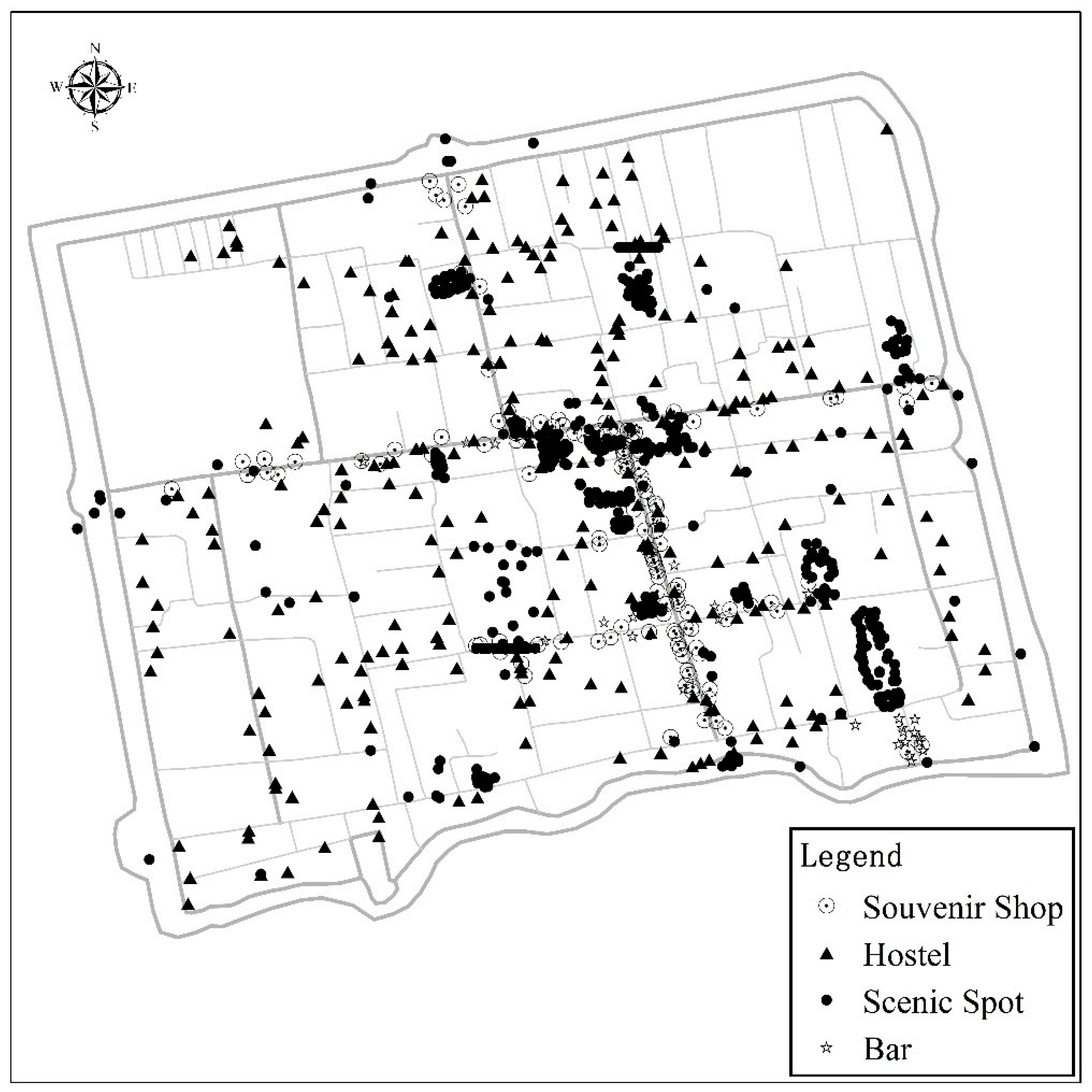

55]. The area has 510 scenic buildings, 260 hostels, 130 souvenir shops, and 27 pubs, as shown in

Figure 4. With increasing tourist visitations and tourist facilities, the ACP has transformed from a primarily living space into a tourist space. Living spaces’ design serves residents’ daily convenience, while tourist spaces are commercialized to serve tourists’ preferences. In this transition, then, most local residents were disempowered spatially and economically.

5.3. Spatial Aspect

In 1992, three experts from the United Nations Center for Human Settlements visited the ACP with Zheng Xiaoxie and Luo Zhewen, and suggested that the Pingyao government should guide local residents to relocate, to reduce the population to 15,000–20,000, in order to conserve the ACP [

56]. These suggestions legitimized the Pingyao government’s encouragement of local residents to relocate outside of the ACP, limited to those who were able to afford the high-priced apartments in the new city of Pingyao. As one interviewee said, “I can’t relocate outside. The cost of a house in the new city is too high for me, but I don’t want to live inside the ACP. There are no hospitals, no schools, no supermarkets for us, and it is too crowded with tourists.”

According to a local official, about 10,000 local residents moved outside the ACP with the relocation of the public living infrastructure, and those who could not relocate have to share their public places with tourists. Their behavior shows their emotional attachment to some of the public places where they used to gather, such as South Street, but which are now occupied by numerous tourists. The stores and shops on South Street used to serve locals’ living needs, but 90 percent of these shops became souvenir stores or other tourist facilities in 2007 [

57], as shown in

Figure 4. One interviewee said, “The ACP belongs to tourists during the daytime, while it is ours during the nighttime,” while another said, “The ACP is occupied by lots of tourists even at night. Sometimes, there are more than 100,000 tourists in one day here.”

Local residents know which reconstructed heritage and invented/performed culture are only for tourists and which are for locals. Recent years have brought many commercial cultural activities and festivals to attract tourists, such as the Pingyao International Photography Festival (PIPF), the Chinese Spring Festival of Pingyao (CSFP), and the newly invented Ancient Performance Activities (APA). These cultural performances bring opportunities for local residents to work as performers, but they distinguish the culture they perform for tourists clearly from their own culture. As one interviewee who works in cultural performance told me, “These performances are only for tourists. We locals are not interested in these … In the past, we didn’t celebrate Spring Festival like this.” What is part of their true past is clear for them.

For locals, these kinds of reconstructed culture for tourists have no cultural roots. For example, when asked if they visited the heritage sites in ACP, one interviewee, age 63, said, “We Pingyao people do not like to visit those heritage tourism sites because they are artificial, just for tourists. In our memory, they were different. Temples are all renewed and reconstructed. When we were young, the temples were schools.” It is clear that, although those reconstructed traditional-style buildings are designed to show the traditional features of the ACP for tourists, they have no relationship to the memories of local residents. In addition, when asked whether they regarded Confucian culture as significant in their daily lives, most replied in the negative. Therefore, while the reconstructed traditional-style spaces show the projected Chinese traditional culture, that culture has not been embraced by the local community.

5.4. Economic Aspect

Some policies that were issued to attract more external investors in tourism development increased the difficulties in local residents’ ability to benefit from tourism. For example, the “Who Funds, Who Benefits” (WFWB) policy states anyone or any organization that restores the traditional buildings as tourist attractions or tourist facilities should benefit from it. Under this attractive policy, sixty-four private investors had restored sixty-eight houses by 2001 [

58], improving the tourist facilities. It is common for external capital for tourist infrastructure and facilities to flow into economically disadvantaged destinations with booming tourist industries [

30,

59] (p. 17), but it leads to competition among local residents for benefits from tourism development. When asked if locals could open traditional inns, one interviewee replied, “I don’t have enough money to decorate my house into an inn … A lot of locals just sell food or work as servers, street vendors … In recent years, even these low-income jobs are competitive because nearby villagers come to do these jobs.”

Some regulations were issued to conserve traditional buildings in the ACP, but these regulations prohibited locals from benefiting freely from tourism development. Many regulations relate to restoring traditional buildings in the ACP, such as the “Shanxi Protection Regulations on Pingyao ancient city”, “Planning on Protecting Pingyao as a NHCC”, and “Detail Planning of the ACP”. In line with these regulations, only nominated companies with official certificates are qualified to restore traditional houses, even if these houses are not authorized as heritage. One of the interviewees said, “There are many regulations for restoring the ancient buildings in ACP. For example, some special materials from the officially nominated companies are used to decorate my house in order to make it look ‘ancient.’ I don’t have enough money to decorate and restore my house that I inherited from my ancestors, so I cannot operate a folk inn or souvenir store.”

Some local residents who have better economic conditions and abilities benefit more from tourism development in the ACP than others. Some local residents decorated and restored their houses into folk inns to provide accommodations for tourists. When I did my fieldwork, I lived in a folk inn operated by locals. The owner, one of my interviewees, told me “it was very difficult at the beginning. I borrowed money from six relatives and three friends to decorate the house. Now, it’s much better from an economic aspect. I should say I am lucky. Without money, many locals don’t have opportunities to open folk inns.” Another interviewee, who rents his house to external investors to operate as a folk inn, said, “It is too complicated to operate folk inns or souvenirs. I do not have that kind of knowledge and skill. I tried in the past, but it felt difficult. It is easier to rent the house to others.” It is clear that tourism development in the ACP widens the gap between rich and poor.

It is the use of heritage structures as objects of management and conservation that determine their value [

6] (p. 3). With more connections to tourism, the buildings in the ACP are evaluated in line with their use as tourist facilities and attractions. Buildings for tourists’ use have more value than do those used by locals, so buildings used by tourists are better restored than are those used by residents. When I undertook fieldwork in the ACP, many residential houses and other places were shabby, while buildings/places for tourists were very well-decorated in the traditional style.

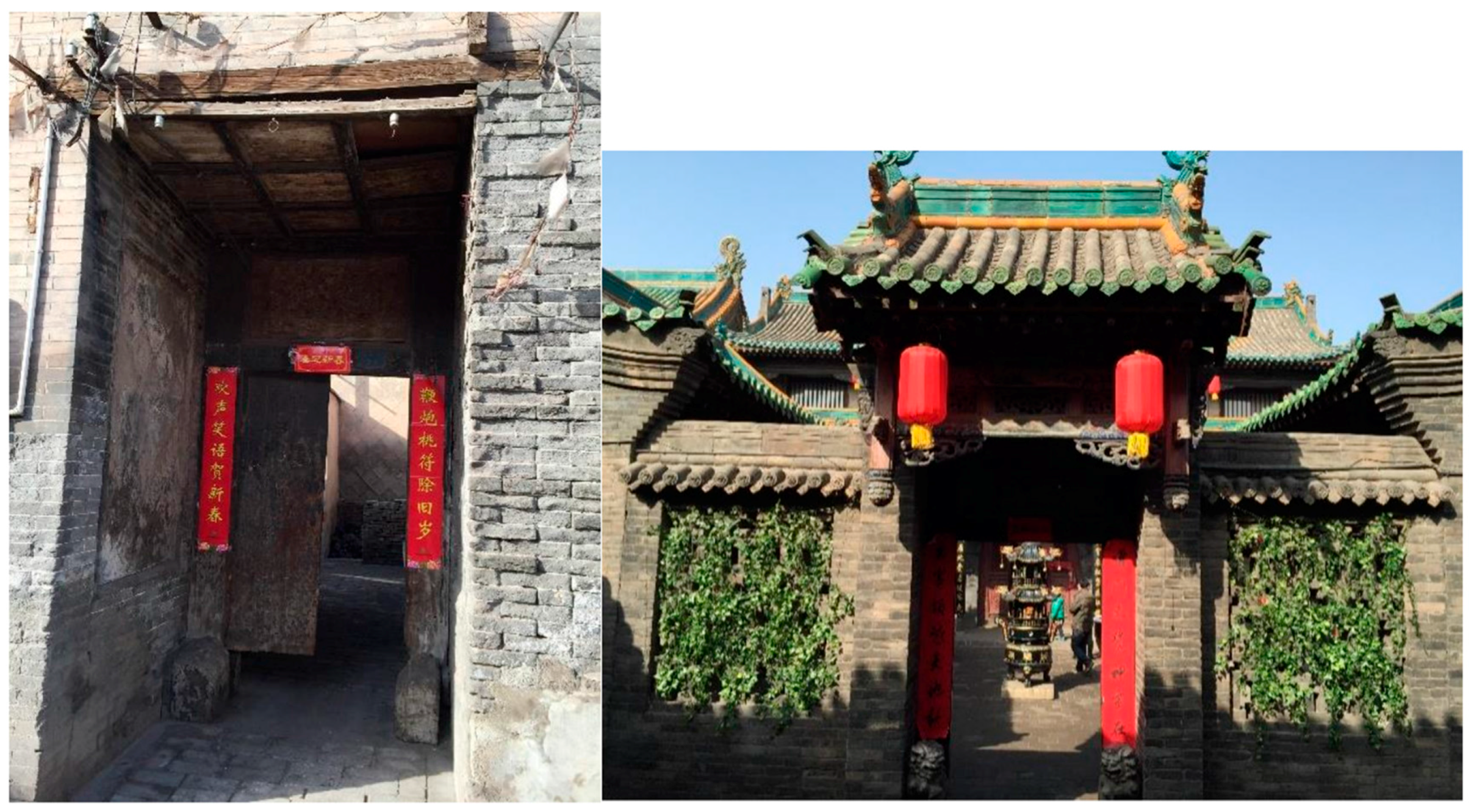

Figure 5 shows differences between tourist inns and local residents’ houses.

It is clear that, since 1978, the ACP has transformed from an enclosed socialist community to a heritage-based tourist destination in which traditional-style culture is purposely reconstructed by both external agents and local actors with the intermediation of local government. The authorized reconstruction of traditional-style buildings/places as heritage through official authentication projects has demonstrated a new social relationship between external heritage experts, external tourism investors, tourists, and local actors since 1978. Heritage authorization is a cultural process in which the heritage sites are tools that use the past to serve the present [

6] (p. 44). Since traditional-style culture is not authentically traditional, but heritage-based touristic culture, and even though the ACP is seen as demonstrating the projected Confucian culture, this traditional culture cannot be injected into locals. In addition, its reconstruction reveals differences in agents’/actors’ social positions in the newly established social relationships.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper examines the transformative process of ACP from a traditional space (that is, “premodern”) to a socialist space in Mao’s era to the current traditional-style commercial space. This process fits Giddens’ time–space distanciation in that the ACP’s spatial transformation is affected by external factors, including World Heritage authorization and touristic commodification. Specifically, the Chinese traditional culture projected in the layout and buildings of the ACP cannot be injected into local people. Furthermore, disembedding mechanics shapes the transformative process in that heritage experts link the international heritage criteria of CCPWCNH to the local practice of the ACP, which connects to tourism-related commodification by means of the reconstruction of traditional-style culture. However, the reconstruction reflects unequal relationships between external agents and local actors in terms of their spatial, economic, and social aspects. The power relationships that underlie the heritage discourse identify certain people who have the ability or authority to speak about heritage and those who do not [

6] (p. 12), so local residents’ restoration/reconstruction of their traditional houses has to be operated in line with heritage regulations and guided by external heritage experts. Furthermore, the absorption of competing external investors with superior economic capital and abilities prohibited local residents from benefiting more from tourism-related commodification, resulting in most local residents without the economic capital being able to do only low-income jobs, such as those of vendors and pedicab drivers [

60]. In this circumstance, local residents in the ACP are situated lower than external heritage experts and investors.

By examining the historical background and the recent transformation of the ACP, this paper also demonstrates the features of heritage modernity driven by the globalization and localization of CCPWCNH implementation. While the CCPWCNH has been heavily criticized for giving heritage experts too much power in evaluating heritage in a hegemonic way [

61,

62] (p. 49), the ACP case reveals the mechanics of the AHD in China, in which heritage experts link international conventions to local practice in a negotiated way. Under these mechanics, only heritage experts have the legitimized power and knowledge power to interpret and claim the “authenticity” of heritage that influences the material or social environment. Therefore, the remains of Mao’s era in the ACP were completely removed through the localization of the CCPWCNH.

In regard to local residents’ responses, this paper analyzes the consequences of heritage modernity as it relates to the effect of heritage authorization and touristic commodification on the formation of local residents’ positions, by illustrating their perceptions of spatial and economic change. As it happens, there is little space for expressions of the local cultural and historical identities of local residents within the homogenizing official discourse of “heritage.” Local residents have been disempowered spatially by the relocation of all public infrastructure and having to share culturally significant public spaces with tourists. In principle, residents around heritage sites carry the living culture of heritage sites and “own” the heritage [

63], and their attitudes influence the sustainable development of heritage sites [

35]. However, the interaction between heritage authorization and tourism development in the ACP results in their detachment from their communities and negative consequences for the integrity of their culture. Furthermore, because of their economically disadvantaged status and the policy of absorbing external investors, most of them have been limited in their ability to benefit from heritage-based tourism development, so they just engage in low-income jobs.

In summary, heritage authorization, per se, does not necessarily lead to the sharing of local places with external actors, but tourism-driven heritage authorization results in local spaces being reconstructed for external tourists. As a result, local residents’ authenticity claims are replaced by those of heritage experts. In this regard, heritage authorization makes it difficult for them to benefit from tourism, particularly because of competition from external investors. It is also clear that tourism development does not necessarily lead to the overt disempowerment of local residents, but heritage-based tourism development demonstrates the underlying disempowerment of local residents. It is the interaction between heritage authorization and tourism development that results in the disempowerment of local residents culturally, spatially, and financially.

This paper, however, did not collect sufficient data from tourists. That is, this research was unable to consider the extent to which the reconstruction of traditional-style culture satisfied the demands and expectations of tourists. During the course of this research, observation of tourist behavior was conducted, yet not to the extent that these behaviors are representative of tourist groups. In other words, how tourists have influenced the reconstruction of traditional-style culture remains unclear. This research is primarily focused on trying to understand how experts have influenced the reconstruction of traditional-style culture. By contrast, the influence of tourists has not been examined. In light of the above, the future direction of research in this area should focus on tourist attitudes towards the reconstructed traditional-style culture and the various ways in which tourists have shaped the transformative processes of heritage-protected tourist destinations.