Building Customer Loyalty in Rural Destinations as a Pre-Condition of Sustainable Competitiveness

Abstract

:1. Introduction and Literature Review

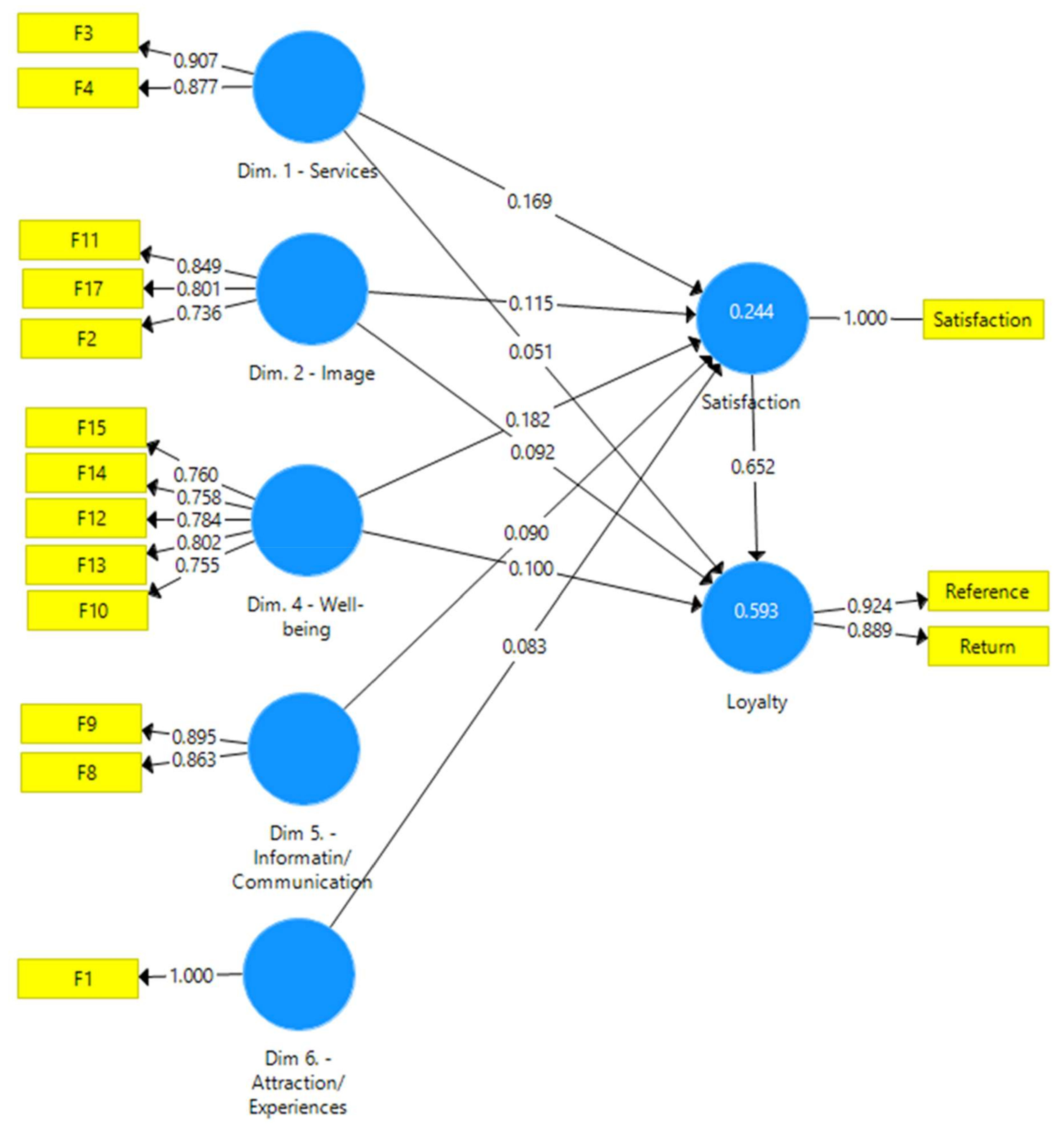

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plog, S.C. Why Destination Areas Rise and Fall in Popularity; The Southern California Chapter of the Travel Research Bureau: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Flagestad, A.; Hope, C.A. Strategic success in winter sports destinations: A value creation perspective. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B. Destination tourism. Critical debates, research gaps and the need for a new research agenda. In The Routledge Hanbook of Tourism and Sustainability, 1st ed.; Hall, C.M., Gossling, S., Scott, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 365–373, ISBN 13: 978-1-138-07147-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.R.; Crouch, G.I. The competitive destination: A sustainability perspective. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S. Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, I.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Our Common Future. United Nations. Available online: http://conspect.nl/pdf/Our_Common_Future-Brundtland_Report_1987.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- WTO. What Tourism Managers Need to Know: A Practical Guide to The Development and Use of Indicators of Sustainable Tourism; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.; Williams, M. Tourism and Innovation; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The Tourism Area Life Cycle: Applications and Modifications; Channel View Publications: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Jamal, T. Touristic Quest for Existential Authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development and New Tourism in the Third World, 2th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Munt, I. The “Other” Postmodern Tourism: Culture, Travel and the New Middle Class. Theory Cult. Soc. 1994, 11, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriely, N. Theories of modern and postmodern tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 982–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, J. The Holiday Makers: Understanding the Impact of Leisure Travel; Heinemann: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Budeanu, A. Sustainable tourist behaviour: A discussion of opportunities for change. Int. Stud. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Grappi, S.; Romani, S. The responsible tourist’s behaviour: An empirical analysis in Italy. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference “Marketing Trends”, Paris, France, 16–17 January 2009; Andreani, J.C., Collesei, U., Eds.; Marketing Trends Association: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter, D.L.; Hou, J.; Lin, C. Profiling Taiwanese ecotourists using a behavioral approach. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric, H.C.; Hunt, J. Ecotourist motivational and demographic characteristics: A case of North Carolina travellers. J. Travel Res. 1998, 36, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Tyrrel, T.J. A Dynamic Model of Sustainable Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2005, 44, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.; Sakata, H.; Thompson, M. Tourist Exit Survey Report: February—September 2012. Annual Patterns of Reef and Rainforest Tourism in North Queensland from Exit Survey Conducted at Cairns Domestic Airport; Report to the National Environmental Research Program; Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited: Caims, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.V.; Fornel, C.; Lehman, D.R. Customer Satisfaction, Market share and Profitability: Finfdings from Sweden. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Service quality, profitability, and the economic worth of customers: What we know and what we need to learn. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.-Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2007, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.K.; Brown, G. Understanding the relationships between perceived travel experiences, overall satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Anatolia Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 23, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, B.C.; Lupton, R.A. Customer portfolio development: Modeling destination adopters, inactives, and rejecters. J. Travel Res. 1997, 36, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A.; Baker, T.L. An Assessment of the Relationship between Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction in the Formation of Consumers’ Purchase Intentions. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A. Tourists’ Destination Loyalty through Emotional Solidarity with Residents: An Integrative Moderated Mediation Model. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.A.M.; Parra-Lopez, E.; Buhalis, D. The loyalty of young residents in an island destination: An integrated model. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 6, 444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Sangpikul, A. The influences of destination quality on tourists’ destination loyalty: An investigation of an island destination. Tourism 2017, 65, 422–436. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Kim, W.; Lee, S. Investigating customer loyalty formation for wellness spa: Individualism vs. collectivism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 67, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaity, M.; Melhem, S.B. Novelty seeking, image, and loyalty—The mediating role of satisfaction and moderating role of length of stay: International tourists’ perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 23, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Rajendran, G. The effect of historical nostalgia on tourists’ destination loyalty intention: An empirical study of the world cultural heritage site—Mahabalipuram, India. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolal, M.; Chi, C.G.; Pesämaa, O. Examine destination loyalty of first-time and repeat visitors at all-inclusive resorts. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1834–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanova, E. Tourism destination image as an antecedent of destination loyalty: The case of Linz, Austria. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 16, 214–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Malek, K. Effects of self-congruity and destination image on destination loyalty: The role of cultural differences. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. Anatolia 2016, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, Z.; Han, F.; Shi, H. Car Tourism in Xinjiang: The Mediation Effect of Perceived Value and Tourist Satisfaction on the Relationship between Destination Image and Loyalty. Sustainability 2017, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral Cuadra, S.; Jimber del Río, J.A.; Orgaz Agüera, F.; Cañero Morales, P.M. The Experience of Service and Loyalty to the Destiny in Tourist Sites: The Case of the Dominican-Haitian Border. Rosa Vent. Tur. Hosp. 2016, 8, 287–300. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-W. Destination loyalty modelling of the global tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Tourism destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2010, 39, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, F. Customer Care. 2001. Available online: https://bookboon.com/cs/customer-care-ebook (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Zabkar, V.; Brencic, M.M.; Dmitrovic, T. Modelling perceived quality, visitor satisfaction and behavioural intentions at the destination level. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeon, S.; Kim, D. The impact of tour quality and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: The case of Chinese tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Bitner, M.J.; Gremler, D. Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus across the Firm, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- CSU, Czech Statistical Office. 2017. Available online: https://vdb.czso.cz/vdbvo2/faces/cs/index.jsf?page=vystup-objekt&z=T&f=TABULKA&ds=ds915&katalog=31737&pvo=RSO13D&c=v61%7E2__RP2015MP12DP31&str=v62A (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Middleton, V.T.C.; Clarke, J.R. Marketing in Travel and Tourism, 3rd ed.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. eTourism: Information Technology for Strategic Tourism Management; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M.; Deegan, J. A Warm Welcome for destination quality brands: The example of the Pays Cathare region. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 5, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronroos, C. Service Management and Marketing: Customer Management in Service Competition, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ryglova, K.; Vajcnerova, I.; Sacha, J.; Strojarova, S. The Quality as a Competitive Factor of the Destination. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equations Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F.; Tepanon, Y.A.; Uysal, M. Measuring tourist satisfaction by attribute and motivation: The case of a nature-based resort. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryglova, K.; Rasovská, I.; Sacha, J. Rural Tourism—Evaluating the Quality of Destination. Eur. Countrys. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklof, J.A. European Customer Satisfaction Index Pan-European Telecommunication Sector Report; European Organization for Quality and European Foundationfor Quality Management: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coban, S. The Effects of the Image of Destination on Tourist Satisfaction and Loyalty: The Case of Cappadocia. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 29, 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gajdosik, T.; Smardova, L. Cooperation of Stakeholders in Urban Tourism Destinations. In Proceedings of the 19th International Colloquium on Regional Sciences, Cejkovice, Czech Republic, 15–17 June 2016; Klimova, V., Zitek, V., Eds.; Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rašovská, I.; Ryglová, K.; Sacha, J. The dimensions and quality factors in urban destinations. Czech Hosp. Tour. Pap. 2016, 12, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Assaker, G.; Vinzi, E.; O’Connor, P. Examining the Effect of Novelty Seeking, Satisfaction and Destination Image on Tourists’ Return Pattern: A Two-factor, Non-linear Latent Growth Model. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Destination | Methodology | Main Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeiro et al. [32] | Island destination | SEM | Results indicate that visitors’ feeling welcomed and sympathetic understanding directly influence loyalty. |

| Gonzalez et al. [33] | Island destination | The discriminant analysis | There are no significant differences in the perceptions of young residents according to gender. |

| Sangpikul [34] | Island destination | SEM | In the case of island destinations, beach attraction is not the only factor contributing to tourist loyalty but people and safety are also essential components to retain loyal tourists. |

| Han et al. [35] | Spa tourism destination | SEM | Quality and value were found to have a critical role, and other study constructs were identified to act as direct/indirect driving forces of loyalty intentions. In addition, a mediating role of affect, satisfaction, and desire was found. Moreover, a moderating impact of culture (individualism vs. collectivism) on the loyalty formation was identified. |

| Albailty, Melhem [36] | United Arab Emirates | PROCESS model tool | Researech confirmed the importance of novelty-seeking and destination image in predicting tourist satisfaction in a destination and destination loyalty. |

| Verma, Rajendran [37] | Cultural heritage site | SEM | The results revealed that historical nostalgia had a significant positive effect on the perceived value, satisfaction, and tourists’ destination loyalty. |

| Yolal et al. [38] | Urban tourism | SEM | This study shows that differences exist between the two groups of visitors—first time visitors value cognitive attributes more and rely more on cognitive evaluation. |

| Iordanova [39] | Linz, Austria | Composite loyalty index | The findings reveal that the better the image, the higher the composite loyalty. Specifically, a destination’s affective image is more influential on tourists’ loyalty than a destination’s cognitive image. |

| Kim, Malek [40] | South Korea | Descriptive statistics, confirmatory factor analysis, SEM | The findings confirmed the influential role of self-congruity and destination image on destination loyalty. |

| Wang et al. [41] | Car tourism | PLS-SEM | The results show that perceived value and satisfaction are direct antecedents of destination loyalty. Above all, perceived value and tourist satisfaction mediate the relationship between destination image and loyalty. |

| Moral Cuadra et al. [42] | Border tourism | Structural analysis | It has been found that there is significant relationship between service experience in a destination and loyalty to the destination. |

| Wu [43] | Global destination | Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) and SEM | Findings from the research sample support the argument that destination image, consumer travel experience, and destination satisfaction are the key determinants of destination loyalty. |

| Characteristics | Sample Structure, n = 775 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 50.5% | Female | 49.5% |

| Age | 18–23 years | 11.3% | 51–60 years | 14.2% |

| 24–30 years | 17.4% | 61–70 years | 13.8% | |

| 31–40 years | 14.3% | 71 and more | 12.6% | |

| 41–50 years | 16.4% | |||

| Education | primary | 21.8% | higher | 28.5% |

| secondary | 49.7% | |||

| Dimension 1: Services | |

| F3 | Accommodation |

| F4 | Food |

| F5 | Social and experiential events |

| Dimension 2: Image | |

| F2 | Cultural monuments |

| F17 | Uniqueness of destination |

| F16 | Overcrowding of the destination |

| F11 | Image of the place |

| Dimension 3: Transportation | |

| F6 | Availability of transportation to the destination |

| F7 | Local transportation |

| Dimension 4: Well-being | |

| F15 | Destination cleanliness |

| F14 | Sense of security |

| F12 | Level of prices of services and goods in the destination |

| F13 | Level of personnel quality in tourism services |

| F10 | Friendly acceptance by the locals |

| Dimension 5: Information/Communication | |

| F9 | Information and communication prior to arrival |

| F8 | Availability and quality of information |

| Dimension 6: Attractions/Experiences | |

| F1 | Natural attractions |

| F18 | Additional infrastructure |

| F19 | Respecting sustainable development of the destination |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryglová, K.; Rašovská, I.; Šácha, J.; Maráková, V. Building Customer Loyalty in Rural Destinations as a Pre-Condition of Sustainable Competitiveness. Sustainability 2018, 10, 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040957

Ryglová K, Rašovská I, Šácha J, Maráková V. Building Customer Loyalty in Rural Destinations as a Pre-Condition of Sustainable Competitiveness. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040957

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyglová, Kateřina, Ida Rašovská, Jakub Šácha, and Vanda Maráková. 2018. "Building Customer Loyalty in Rural Destinations as a Pre-Condition of Sustainable Competitiveness" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040957

APA StyleRyglová, K., Rašovská, I., Šácha, J., & Maráková, V. (2018). Building Customer Loyalty in Rural Destinations as a Pre-Condition of Sustainable Competitiveness. Sustainability, 10(4), 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040957