Abstract

The concept of sustainable management in culture has been recognised in global strategic documents on sustainable development for more than a decade. It is also increasingly reflected in the cultural polices of particular states, and—very importantly—cultural managers who are responsible for shaping the cultural offer in cities are becoming more interested in this concept. Despite the increasing attention being paid to this topic among both practitioners and theoreticians of management, in none of these documents or other works can we find any content that is directly related to the possibility of applying this concept in a town which, due to political turmoil, has been divided by a national border. Hence, this gap was the direct impulse for taking up research in this field. In the article, by using different notions of the market, our own definition of a cross-border market for cultural services was developed, and the conditions for the functioning of this market were presented based on the example town of Cieszyn (Poland) and Český Těšín (Czech Republic). In the opinion of the authors of the article, the development and functioning of a cross-border market for cultural services is essential for the application of the concept of sustainable management of the cultural offer in a town divided by a border. For the purpose of the article, a survey and individual interviews with experts shaping the cultural offer in Cieszyn and Český Těšín were conducted. The results of the research prove that despite numerous cross-border Czech–Polish projects carried out by cultural institutions, there are still many barriers in the town, which make it difficult for the residents to benefit from the cultural offer that is available on the other side of the border. These barriers limit the full implementation and application of the concept of sustainable management of the cultural offer.

1. Introduction

The term “sustainable development” or “sustainable resource management” is attributed to Hans Carl von Carlowitz, who used it in relation to the treatment of forests that he managed in Saxony (Germany) in the 18th century. His main idea was to preserve the existence of the forest; he thus formulated and implemented such concepts as the rule of cutting only as many trees as could grow in their place in the relevant period of time. He noticed that a forest can exist without man, whereas man cannot exist without the forest. Hence, he protected forest resources against exploitation, although it could have brought a significant and rapid increase in income. At the same time, he harvested timber, not only for nurturing, but also for economic reasons, in order to obtain funds for the preservation of the forest [1,2]. This model quickly spread in forestry across the whole of Germany, and later it was also adopted by other countries in Western Europe. In the 21st century, this solution is successfully implemented in the field of culture as well. In the same way that there is no man without a forest, there is no man without culture. One cannot measure or calculate what is existential and what forms the basis for human existence. One cannot answer the questions: “Who am I?” and “What am I doing here?” without culture that is understood in the broadest sense of the word. An attempt at measuring and estimating the existential value of culture is the same kind of misunderstanding as calculating the existential value of a forest. Hence, in accordance with the concept of the sustainable management of culture, we must finance culture in order to exist, and not in order to earn money; otherwise, it would lead to the degradation of humanity as a society and prevent its development, also in terms of economy.

The first global document (signed by more than 650 cities, self-governments, and organisations from all over the world), raising the problem of sustainable management of culture, and thus establishing the rules and obligations of cities and self-governments in the context of cultural development was Agenda 21 from 2008 [3]. Two years later, this document was amended by the United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG)—a global network of cities, self-governments, and municipal associations from the 120 countries associated in the United Nations (UN)—at the International Congress in Mexico, where the elaboration entitled Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development [4] was approved. This document directly indicates the relations between culture and sustainable development. It deals with sustainable development in the context of developing a cultural policy in which culture is treated as a driving force for development; it also mentions the promotion of the cultural dimension in all public policies (culture as the development factor). The third of the global documents (and so far, the last one) was the declaration entitled Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies, also known as the Hangzhou Declaration—the name derived from the city in China where in 2013, the International Congress of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) devoted to links between culture and sustainable development was held [5]. At this congress, with the participation of the global community and the main interested parties: cultural practitioners, managers, and scientists performing research in this field, the ways of strengthening the role of culture in the worldwide debate on sustainable development were discussed, as well as the adoption of culture as the driving force for all development.

The three documents mentioned above did not remain as only empty records, as they quickly found their references in the global cultural policy. This can be proved by strategies of implementing the concept of sustainable development in the cultural context, such as the common document of International Federations of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies (IFACCA), Coalitions for Cultural Diversity (IFCCD), and Agenda 21 for Culture and Culture Action Europe: Culture as a Goal in the Post-2015 Development Agenda. In this document, which is the result of cooperation between government and self-government organisations and cultural environments in general, there is a statement about ensuring cultural stability for the well-being of all.

Among other important strategic documents, it is also worth mentioning the work entitled “Culture 21: Actions–Commitments on the role of culture in sustainable cities”, which through relevant additions, supplements Agenda 21 in terms of culture, and transforms it into specific obligations and actions [6]. At present, this document serves as an international guide and a set of specific solutions (tools) for cities, aimed at supporting activities and cooperation between city authorities, managers of cultural institutions, and residents. This document contains guidelines constituting a basis for building a strategy for the development of sustainable culture, as well as the sustainable offer of cultural institutions at a local level. One of the guidelines is the balance between the strategic goals of cultural institutions, on the one hand, and the expectations of the recipients of the cultural offer on the other. Unfortunately, none of the aforementioned documents contains guidelines concerning sustainable management in culture, the sustainable management of the offer of cultural institutions in a town divided by a border, or the development of a cross-border market for cultural services. In this area, there is a considerable research gap. The very lack of a definition of the cross-border market for cultural services was a direct impulse to engage in this topic.

In addition, over the last twenty years, along the borders of member states of the European Union, including the Polish and Czech border, the intensification of various types of activities aimed at supporting cross-border cooperation in the field of culture can be observed [7,8]. Among other things, these activities serve to blur the borders and divisions between the local communities, and to shape their new quality (they should become a place of meetings, and not divisions) [9,10]. On the Polish and Czech border, in particular in town divided by a border, such as Cieszyn-Český Těšín, it is expressed in the growing number of cultural events that are being organised, and which are often implemented as part of cross-border cultural projects co-financed from the funds of the European Union [11,12]. Nevertheless, this situation poses new challenges for the managers of the cultural institutions of Cieszyn and Český Těšín, and requires the implementation of the concept of the sustainable management of culture and the rules of sustainable management by the offer of cultural institutions [13]. This, however entails taking responsibility for culture, which, on the one hand, requires an even deeper examination of the cultural offers available on both sides of the border (its quality, its saturation with artistic content, or its availability), and on the other hand, is determined by an in-depth analysis of the needs of both Polish and Czech addressees of this offer. Hence, one of the main goals of the article was to find out how frequently the residents of a town divided by a border participate in cultural events that are organised on both its sides, as well as to identify the main barriers which make it difficult for the inhabitants to benefit from the cultural offers available both on the Polish and the Czech side of the border. Barriers that should be overcome, along with the implementation of the concept of sustainable management of culture were identified. The conclusions from the research and the recommendations contained in this article may be a contribution to the debate on the conditions for the development of a cross-border market for cultural services, or the possibilities of the application of the concept of sustainable management in the offers of cultural institutions in other cities (in particular, cities in the European Union), which similarly to Cieszyn and Český Těšín, have been divided by a national border.

2. Materials and Methods

Before discussing the methodology used in the research on the cross-border market for cultural services in Cieszyn and Český Těšín, it should be explained how the authors understand the issue of the cross-border market for cultural services. Source literature does not mention such a term, which may indicate a clear research gap in this area.

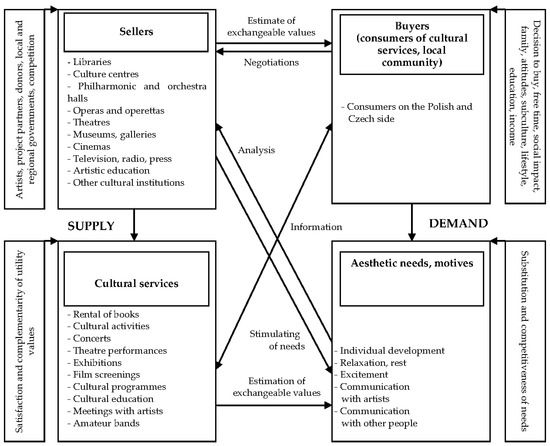

In attempting to define the cross-border market for cultural services, both the economic and geographical market definitions were used, according to which the cross-border market for cultural services was the entirety of the exchange relations between service providers that meet cultural needs and the consumers purchasing these services in the regions of the countries sharing a common border. In other words, it will be a collection of buyers (consumers of cultural services, mainly the local community) and sellers (self-government and government cultural institutions, third-sector cultural institutions and other cultural entities) who carry out transactions regarding cultural services in areas along the border of the countries (border and cross-border regions). A geographical understanding of the cross-border market for cultural services indicates a territory that is located on both sides of the border (in the present case, between Poland and the Czech Republic), as a separate area with similar purchasing and selling conditions. The classic (economic) understanding of the market reduces the definition of the cross-border market for cultural services to the general exchange relations between sellers, offering services that meet cultural needs and buyers, representing the demand for these services. It includes both the subjective (who participates in the trading process) and the objective aspect (what is the object of trade)—Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure of the cross-border market for cultural services.

The cross-border market for cultural services should therefore be treated as a system whose elements form a specific structure. In this system, we can distinguish [14,15]:

- (i)

- market entities, i.e., the sellers (cultural institutions, third-sector cultural organisations, other cultural entities) and the buyers (consumers of cultural services, mainly the local community);

- (ii)

- market objects, i.e., cultural services and aesthetic needs, motives for using the services of cultural entities available on the market);

- (iii)

- relations between market entities and objects.

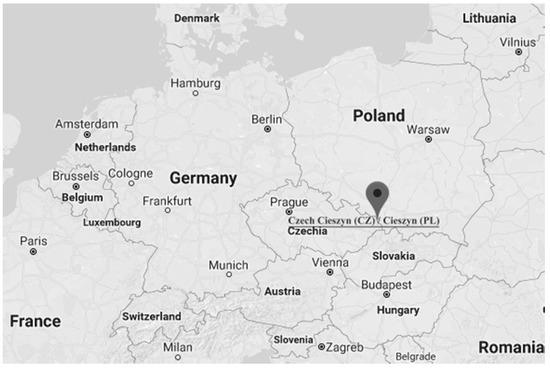

In this article, the analysed field is a town which, due to political decisions made at the end of the First World War, has been divided for a hundred years into Cieszyn (49°45′04″ N, 18°37′55″ E) on the Polish side of the border (approx. 36,000 inhabitants) and Český Těšín (Czech Republic, 49°44′46″ N, 18°37′34″ E, approx. 25,000 inhabitants)—Figure 2. In 2007, both cities joined the so-called Schengen Zone and became subject to visa-free travel without border control.

Figure 2.

The location of the border cities Czech Cieszyn (CZ)/Cieszyn (PL).

The Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services in these cities, functions on many different levels. It concerns not only economically significant activities, such as the investment “A Garden on Both Banks of the River” (co-financed from the funds of the European Union under the European Regional Development Fund), which connects the two towns, but also flagship events, such as the largest event in the town in terms of attendance, the Three Brothers’ Festival. However, the key to the sustainable management of cultural services in the cross-border market for cultural services is the commitment and common responsibility for the cultural offer on the part of self-government authorities, managers of cultural institutions, and the citizens involved (the commitment of the latter is visible e.g., in the third-sector cultural organisations functioning in the town). Currently, cooperation between Polish and Czech municipal authorities and the third sector is operating on many levels. Self-government authorities and the managers of self-government cultural institutions are involved in nearly all of the larger events that organised by representatives of the third sector. This concerns many small initiatives as well as international events which have contributed to the development of the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services for many years. These include, in particular, such events as the Film Festival, “Kino na Granicy” (Filmová přehlídka Kino na hranici) or the Theatre Festival, “Bez Granic”.

The supply side of the cross-border market for the cultural services of Cieszyn and Český Těšín is represented by a number of institutions whose offer is not limited to only one side of the river running along the national border. Despite its small size, the town boasts two theatres. On the Polish side, it is Adam Mickiewicz Theatre; on the Czech side, it is a theatre with both a Polish and Czech stage. Interestingly, the Polish stage located in Těšínské Divadlo is financed by the Czech Marshal’s Office without any subsidies from Polish sources. In the town as a whole, two large cultural centres are active: Cieszyn Cultural Centre “Dom Narodowy” and Kulturní a společenské středisko Střelnice. Other important cultural places include: the Municipal Library in Cieszyn, the Municipal Library in Český Těšín (Městská knihovna Český Těšín), a reading room and literary cafe Avion (Čítárna a kavárna Avion), the internationally recognised and design-oriented Cieszyn Castle, the Museum of Cieszyn Silesia and the Cieszyn Library, which boasts a number of unique publications from the last five centuries. Within the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services, many associations are active. The most visible ones include: the “Olza” Association of Development and Regional Cooperation, Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion, Polish Cultural, and the Educational Union in the Czech Republic, the Congress of Poles in the Czech Republic, Association “Kultura na Granicy” (Culture on the Border), Association “Člověk na hranici” (Man on the Border), Polish–Czech-Slovak Solidarity, and Association “Education Talent Culture”. The many privately-owned initiatives and places, playing a more or less significant role, should also be mentioned. Such places are also important for the development of the cross-border market for cultural services, and the sustainable management of the cultural offer on this market. Examples of such places are: Literary Cafe “Kornel i Przyjaciele”, Teahouse “Laja”, Club “Dziupla”, Bar “Blady Świt” (Bledý úsvit), as well as such cultural events as a cycle of charity concerts entitled “Aktywuj Dobro”.

The main purpose of the conducted research was to determine how often the residents of the town divided by a border participate in cultural events organised in Cieszyn and Český Těšín, as well as to define the main obstacles that make it difficult for residents to benefit from the cultural offer available abroad (in the neighbouring country). These obstacles present a challenge for the managers of cultural institutions in the process of the sustainable management of their offer. Three research hypotheses were adopted, according to which it is assumed that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

The range of impact of the offer of Polish cultural institutions located in Cieszyn is limited to the Polish side of the town.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

The range of impact of the offer of Czech cultural institutions located in Český Těšín is limited to the Czech side of the town.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

The main barrier that hinders the residents of both Cieszyn and Český Těšín in making use of the cultural offers available on the other side of the border is a lack of interest in the neighbouring country’s culture.

In order to verify the adopted hypotheses, a survey was conducted on a group of 799 residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín—which constitutes approx. 1% of all of the inhabitants of the town on both sides of the border. The group consisted of persons who, in 2017, participated at least once in any cultural event organised in the town divided by a border. The survey was carried out using the PAPI (Paper and Pen Personal Interview) and the CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interview) technique. The survey questionnaire was developed in both Polish and Czech. Electronic questionnaires were made available to the residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín on the following websites: https://goo.gl/forms/Gu7E23zM9uFxgVfD2 (questionnaire in Polish), https://goo.gl/forms/eS2GwmnaMQ40k3NU2 (questionnaire in Czech). Basic information about the conducted research is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic information about the conducted research.

Pierre Bourdieu indicates not without reason that “the mysteries of culture have their catechumens, their initiates, their holy men, that ‘discrete elite’ set apart from ordinary mortals” [16]. Although this statement seems to be a mental shortcut, it is beyond doubt that on the territory of a divided town, such as Cieszyn and Český Těšín, it is possible to find experts who, owing to their education and functions performed in the field of broadly understood culture, have a more extensive and detailed knowledge than other residents of the town. Therefore, in order to obtain a more complete picture of the issues analysed in this article, complementary research was conducted using the interview method in the form of individual in-depth interviews (IDI) with 40 experts—directors of cultural institutions, creators, animators, and organisers of cultural events in Cieszyn (20 persons) and Český Těšín (20 persons)—Table 2.

Table 2.

Experts participating in the in-depth interviews.

The interview questionnaire (in Polish and in Czech) contained 17 questions in total, seven of which were short, based on association and completion, while the remaining 10 questions were open and in-depth.

The survey was conducted among the residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín between October 2017 and January 2018, while the interviews were carried out between February and June 2018. The survey was preceded by consultations with employees of the Cultural Department of the Town Hall in Cieszyn and Český Těšín. The purpose of the consultations was to check the correctness of the research assumptions as well as to test the research tools being developed. Discussions in the relevant groups enabled the final version of the questionnaire and guidelines for the interview to be refined, as a result of which it was possible to start the main research. This article is limited to the presentation of selected results of the research which were relevant for the verification of the adopted research hypotheses.

The research was part of the project entitled “Programme for the Culture of Cieszyn and Český Těšín” co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund—Interreg V-A Programme Czech Republic—Poland as part of the Micro-Projects Fund of the Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion—Těšínské Slezsko and the state budget.

In order to obtain reliable results, an inductive method was used, i.e., the method of incomplete numerical induction. It is inductive reasoning, the premises of which do not exhaust the entire universe of objects to which the general principle expressed in the conclusion of the reasoning refers. Here, the premises are specific sentences, while the conclusion is a general sentence, and each premise follows logically from the conclusion. It is a method by which a general principle is derived from a limited number of details [17,18].

3. Results

Coming to the main part of the analysis, it must be indicated that the obtained results of the conducted survey, due to the sampling method applied (in the survey, non-random sampling methods were used—targeted selection), provides knowledge about the respondents’ opinions on the selected behaviours of the residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín at the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services, and not the factual state in this scope. However, it is necessary to bear in mind the large size of the research sample, as well as the reliability and goodwill of the respondents.

One of the main issues examined was related to the frequency of benefiting from the cultural offer. The residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín were asked about how often they made use of the cultural offers of institutions and cultural entities located in Cieszyn (on the Polish side) and Český Těšín. The results with a division into residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency of making use of the offers of cultural institutions and entities in Cieszyn and Český Těšín in 2017 by residents (in %, on average).

The data presented in Table 3 shows that the vast majority of the residents of Cieszyn (69%) had not made use of the offer of the cultural institutions located in their town. The cultural institutions that were visited by Polish respondents in 2017 usually included the Municipal Library in Cieszyn—21% of respondents, the Cieszyn Castle (17%)—here, however, in the course of further in-depth research, it turned out that the respondents first of all had in mind a walk around the Castle Hill, but not a visit to, for example, one of the Cieszyn Castle exhibitions, as well as the “Piast” Cinema (17%). The situation was even less optimistic regarding the inhabitants of Český Těšín. In 2017, as many as 84% of inhabitants did not even once use the cultural offer available on the Polish side of the town. The remaining inhabitants of Český Těšín most often visited such cultural institutions on the Polish side as: Cieszyn Castle (11%)—similarly as in the case of Poles, visiting the Cieszyn Castle was most often in the form of a walk around the Castle Hill, “Piast” Cinema (5%), and the Municipal Library in Cieszyn (3%), which Poles living in the Czech Republic (members of the Polish Cultural and Educational Union in the Czech Republic) most often use (Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequency of making use of the offer of cultural institutions and entities in Cieszyn in 2017 by residents (in %).

The presented data also show that Poles living in Cieszyn very rarely visit cultural institutions that are located on the other side of the border. The Těšín Theatre is the cultural institution in Český Těšín which enjoys the greatest interest among Poles. Nearly 5% of the surveyed residents of Cieszyn visited this institution in 2017 four or many times, 5% of the Cieszyn residents surveyed visited the Těšín Theatre 2–3 times and 12% of them did so once. Such a result could have been expected given the fact that the Theatre located in Český Těšín, in addition to the Czech theatre group, features a “Polish Stage”—a group of Polish actors putting on plays in Polish. The surveyed residents of Český Těšín declared, in turn, that in Český Těšín they most often made use of the offer of the literary café AVION, which is located in the immediate vicinity of the “Friendship Bridge” connecting Cieszyn with Český Těšín. In 2017, Café AVION was visited four or many times by 22% of the surveyed Český Těšín residents. In addition, the Municipal Library in Český Těšín was visited 4 or many times by 21% of Czech respondents, and the Těšín Theatre—by 20% of the surveyed residents of Český Těšín (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of making use of the offer of cultural institutions and entities in Český Těšín in 2017 by residents (in %).

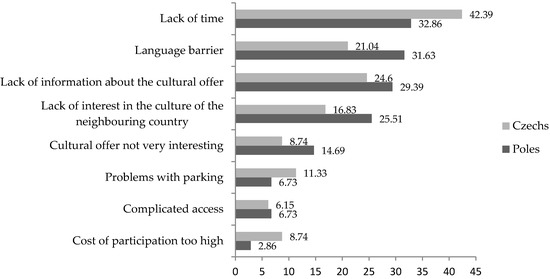

Another issue which was examined was related to barriers making it difficult for the residents to benefit from the cultural offers of Cieszyn and Český Těšín. In the opinion of the interviewed experts, the main barrier hindering access to the cultural offer in the neighbouring country was the language barrier (85%) and the lack of information about the cultural offer on the other side of the border (80%). Despite the fact that the Polish and Czech languages belong to the same group of Slavic languages and are very similar to each other—showing many common features (e.g., vocabulary, grammar, and inflection), specialised vocabulary in some thematic areas (including the area of culture) is, however, quite different in the two languages. Residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín communicate with each other using a colloquial language (a mix of Polish and Czech languages) in everyday, simple situations (e.g., when shopping or using public and intercity transport in both cities), however, difficulties often occur in communication when it becomes necessary to understand specialist or literary language (e.g., technical language or the language used by artists and culture organisers). Although the language barrier on the Polish–Czech or Polish–Slovak border is much smaller than, for example, that on the Polish–German or the Franco–German border (where they have completely different language groups), the people responsible for developing a sustainable cultural offers in Cieszyn and Český Těšín should not underestimate it—as shown by the results of surveys conducted among the residents (Figure 3). The residents of both cities, not knowing the language of the neighbouring country well, can take advantage the offers of museums, galleries, or symphonic orchestras located on both sides of the border without any obstacles, but they may have difficulties understanding the content of the offers of cultural institutions, such as cinemas or theatres. Therefore, common language education is necessary to overcome this barrier. Unfortunately, such education in Cieszyn and Český Těšín is incidental. Although, of course, there are primary and secondary schools in Cieszyn and Český Těšín where additional extracurricular activities in the Polish and Czech are conducted, there are, however, too few of them, and the obligatory foreign language taught at schools in both Cieszyn and Český Těšín is currently English. It is also worth noting here that the language barrier is more of a hindrance to Český Těšín’s cultural offer for Poles (around 32%) than the reverse—for residents of the Czech side of the city (around 21%). This is related to the fact that a large Polish minority lives on the Czech side, even having its representative in the municipal authorities (one of the deputy mayors of Český Těšín declares Polish nationality and is fluent in Polish).

Figure 3.

Barriers hindering the access of residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín to the cultural offer of the neighbouring country (in %). The results do not add up to 100 because respondents could tick more than one answer.

In addition, according to the majority of the interviewed experts (65%), an important reason for the residents not making use of the cultural offer was the low position of culture in their hierarchy of needs, which was directly related to a lack of proper preparation for the reception of culture. At this point, attention was drawn to the deficiencies in the cultural education, which were provided in primary and secondary schools both on the Polish and the Czech side. It is worth remembering that Polish–Czech cross-border cultural education means better preparation for participation in culture, i.e., participation in the artistic and cultural activities of both the Polish and Czech society. This education in both cities must first of all meet the needs of the young generation, both in terms of form and content of the message. It can take the form of e-learning education or through the use of suitable internet applications available for mobile devices, e.g., smartphones or tablets. In the process of cultural education, increased emphasis should be placed on the active participation of people in cultural events in the cross-border dimension of culture, and overcoming the stereotype of the passive reception of culture. However, the key task of cultural education in Cieszyn and Český Těšín is, above all, the development of cooperation between cultural institutions and organisations, and both primary and secondary schools. The program of joint Polish–Czech cultural education should be born at the “cross-border round table”, in order to jointly develop its concept, which would then be implemented in parallel in Polish and Czech schools. It is also extremely important to increase the scope of hobby and artistic activities in self-governmental cultural institutions and non-governmental organisations. This will allow cultural education to combine with social integration.

The experts also indicated that the cultural offers for both Cieszyn and Český Těšín were very chaotic (63%), and the residents of both the Polish and the Czech side had difficulties in finding or understanding them. Moreover, many cultural events overlapped with one another. The problem of common Polish–Czech promotion, or rather the lack of such promotion, was also raised (60%). It would seem that in a town divided by a border, information placed on posters or even on the websites of cultural institutions should be available both in Polish and in Czech. Unfortunately, an analysis of the websites of all the self-government cultural institutions of Cieszyn and Český Těšín proves that usually this is not the case [19,20]. The offer of the Polish cultural institutions does not reach the other side of the border—similarly, the cultural institutions in Český Těšín do not really strive to attract the Polish audience from Cieszyn. Moreover, barriers of a legal nature were indicated, such as the lack of the possibility for students from the Polish side to freely attend cultural events organised on the Czech side, or the need to buy additional insurance for the students. Experts (40%) also highlighted the so-called “provincial closure”—in their opinion, the residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín are simply not interested in the culture of the neighbouring country, and the cultural offer available on the other side of the border, which is also proven by the results of the survey conducted among the residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín. However, the survey shows that the inhabitants of Český Těšín are more interested in Polish culture than the inhabitants of Cieszyn are interested in Czech culture (it probably results from the fact that in Český Těšín a large Polish minority is still present and active). In addition, the residents of Český Těšín (16%) cross the border more often than the residents of Cieszyn (11%) in order to benefit from the cultural offer available on the other side of the border. In our opinion, it is worth mentioning that the organisers of the cultural life themselves are less affected by the aforementioned “provincial closure”. In the light of other research, these persons usually have an intrinsic awareness of their position in the structure of the local, peripheral community. However, the word “province” does not have a negative meaning here. It is associated with a number of advantages, and even some kind of pride in living in the periphery. The main barriers hindering access to the cultural offer in the neighbouring country, according to the interviewed residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín, are presented in the Figure 3.

According to the respondents, the main barrier that hinders the residents of both Cieszyn and Český Těšín in making use of the cultural offer available on the other side of the border, both for Poles and for Czechs, is a lack of time (33% and 42% of respondents respectively), which may indicate that the cultural needs of the respondents are not among their priorities. This state of affairs (the low position of culture in the hierarchy of needs) was indicated by 65% of the interviewed experts. For Poles, an almost equally important barrier hindering the use of the cultural offer of Český Těšín is the lack of knowledge of the Czech language (32%), followed by the lack of information about the cultural offer available in the neighbouring country (29%) and the lack of interest in the culture of the neighbouring country (26%). The same barriers (although in a slightly different order) were indicated by the residents of Český Těšín in relation to the cultural offer available on the Polish side of the border (Figure 3).

Despite the indicated barriers, most of the interviewed experts (70%) stated that the cooperation between the cultural institutions from Cieszyn and Český Těšín was good and enabled further development of the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services. This can also be proven by:

- (i)

- the important position of culture in the strategic documents of both towns, the Cieszyn county, the Cieszyn Silesia Euroregion, and the provinces on both sides of the border [21,22],

- (ii)

- a large number of various types of entities: public, commercial, and non-governmental, dealing with culture on both sides of the border [23,24],

- (iii)

- the great importance of culture as an element function in other areas that are important in the socio-economic development of the whole region (e.g., tourism) [25,26],

- (iv)

- the multiplicity and relative durability of bilateral partnerships based on cross-border projects in the field of culture, including, in particular, projects that are co-financed by the European Union, which foster the strengthening of cross-border cooperation [27,28].

However, the majority of experts (65%) admitted that in order to effectively implement the concept of the sustainable management of the offer of cultural institutions in a town divided by a border, the cooperation between cultural institutions should be much more intense in such fields as:

- (i)

- common cultural education,

- (ii)

- common Polish–Czech promotion of organised cultural events,

- (iii)

- common calendar of events,

- (iv)

- common public transport.

The importance of the better coordination of cross-border activities was also highlighted. At present, this coordination takes place mostly at a national level (separately on the Polish and the Czech side), while there is a lack of coordination at the transnational, cross-border level.

4. Discussion

Sustainable management of the offers of Polish and Czech cultural institutions—cooperation in the field of culture between Cieszyn and Český Těšín, is one of the basic forms of cross-border activity aimed at “blurring the borderline” on this section of the Polish–Czech border. Its aim is to strive to strengthen the harmonious development of both twin towns and the cohesion of the entire Cieszyn Silesia region. Thanks to joint Polish–Czech projects, cultural institutions functioning both on the Polish and the Czech side of the town are shaping the common locality of the two towns, not only because of the spatial closeness, but also due to the ability of social reproduction [29,30]. Many activities and events are of a cyclical nature, and some of them have a long-standing tradition. However, the results of the conducted research show that over 84% of the surveyed residents of Český Těšín have never made use of the cultural offer that is available on the Polish side of the border. Therefore, it can be assumed that the range of impact of the Polish cultural institutions located in Cieszyn is limited mainly to the Polish side of the borderland. Similarly, the spatial range of the impact of cultural institutions operating in Český Těšín is usually limited to the Czech side of the town (89% of the surveyed residents of Cieszyn have never benefited from the cultural offer available in Český Těšín). Therefore, the hypotheses H1 and H2, assuming that the range of impact of the offer of cultural institutions located in Cieszyn or Český Těšín is limited mainly to the part of the town in which they function, proved to be true. This was also confirmed by the results of former research in Cieszyn and Český Těšín, which showed that the division into Poles and Czechs is still very visible among the residents of both towns [7,22], and therefore the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services is still at an early stage of development.

The functioning of the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services in a town divided by a border and its importance for the social environment is determined by many complementary factors. From the perspective of cultural institutions and cultural offer management, these factors oscillate around the balance between the identification of the cultural needs of various social groups and the possibilities of pursuing articulated goals, which are often included in the strategic documents of the town, or in the statutes and development strategies of cultural institutions. The entities responsible for shaping the cultural offer include, among others, self-government and national institutions (in this case, one should say “government” institutions). In the development of modern societies, in the system of entities shaping the cultural environment, apart from the aforementioned organisations, the so-called third sector organisations (often abbreviated as “NGO” for non-governmental organisations) and private organisations have gained importance.

The fact that a national border exists, and that it cuts through the analysed town of Cieszyn-Český Těšín is, in this case, a socio-political factor. This factor poses a great challenge to the managers of cultural institutions that are responsible for shaping the cultural offers that are available for the residents of both the Polish and the Czech side of the town. The border and the attachment to the given nation in the described area is not illusory, although both sides belong to the European Community and the Schengen Zone. Even if we treat this national adherence as “(…) an imagined political community—and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign” [31], the matter of this symbolic attribution to the national community cannot be omitted in the light of these considerations.

Despite the opening of the borders and the functioning of cultural institutions, both on the Polish and the Czech side of the town, as well as the social and cultural capital of this area, is still connected with the history. What is more, it concerns not only contemporary history, but also that which dates back hundreds of years. Natural migration flows and politics have played an important part in this process. Particularly significant changes in the national composition of the population affected the Czech side of the town. The population formerly prevailing in this area, declaring themselves to be Poles, currently comprises only a few percent of all inhabitants. This change of composition was caused by political reasons aimed at the marginalisation of the former inhabitants of the town. Economic reasons related to the economic development of the town and its surroundings were also not without importance. These changes in the population structure have a fundamental meaning for the sustainable management of the cultural offers and cultural institutions and the cross-border market for cultural services. The recipients of the cultural offers of Cieszyn and Český Těšín look at their place of residence from totally different perspectives. New inhabitants brought to Český Těšín in the second half of the 20th century, coming from remote regions of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, are not rooted in this area and therefore lack a basis, which constitutes human identity in a fundamental way [32]. On the other hand, those residents who can trace their roots even back to the late Middle Ages, by glorifying the past of their town, often fail to notice its current needs.

The past and socio-political changes largely determine the cultural offers of the cultural institutions functioning in the town. In the described region, the Olza river, running along the national border, forms a kind of a mental barrier, which, despite the formal dissolution of the borders, is nurtured in the hearts of the residents on both sides of the river. Regardless of the right to cross it freely, the existence of the border has its consequences for the self-identification of the residents and thus the functioning of the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services. At this point, it is worth indicating that Poland and the Czech Republic are currently at a similar level of development. In the category of competitiveness, both countries are ranked relatively high in “The Global Competitiveness Report” for 2016–2017 [33]: they are listed among the 30 most competitive countries. Both nations also attach importance to similar values, such as family and health. In addition, both Poles and Czechs have a low level of confidence in politics. Apart from the numerous similarities that could be indicated here, one area significantly differentiates the two nations. It is their approach to religion. According to the findings of the “Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism”, 81% of Poles deem themselves to be religious, compared to only 20% of Czechs. In terms of religiousness, residents of the Czech Republic, despite their close proximity to Poland, are closer to such countries as China or Japan, which have the highest percentage of declared atheists [34]. The matter of the approach to religion is not without significance here, as it is one of the aspects which can influence mutual trust and the understanding of attitudes of the residents on both sides of the border, as well as the mutual sympathy or antipathy expressed by them. These problems may directly affect the cultural offers of cultural institutions and, therefore, the functioning of the cross-border market for cultural services. Despite the aforementioned differences, it is the average Pole, out of all the nations in the world, that has the greatest liking for Czechs. On the other hand, the same rankings prove that Czechs are not as fond of Poles. However, it is worth observing that as a national minority (and in the town of Český Těšín, which is discussed here, Poles constitute a significant minority), Poles are ranked very highly by Czechs.

The aforementioned conditions are only some of the problems that are present in the everyday life of the divided town of Cieszyn and Český Těšín that managers of cultural institutions have to face in their attempts at creating a cultural offer that is addressed to the residents of the both sides of the border. However, their efforts are often misunderstood and confronted with a strong sense of distinctness, often involving reluctance and various forms of chauvinism or xenophobia. This reluctance may be expressed by a dismissive attitude towards the inhabitants of the “other side”, verbal jokes, or indifference. It can also be acute in social situations, for example, in the manifestation of dislike towards representatives of the foreign nationality in public places. However, among the residents of both towns, the prevailing attitude is a mere lack of knowledge about the other nation. Hence, persons and institutions involved in cultural life assume a special kind of responsibility, where the local and national interests are often complementary, but sometimes mutually exclusive. At the same time, although it smacks of irony, many important cultural events and institutions—which, by definition, are supposed to connect both towns—have the word “border” in their name.

This state of affairs, in turn, makes it difficult to fully implement the concept of the sustainable management of the offer of cultural institutions in a town divided by a border. According to the interviewed experts, the main barriers (problems) that will have to be faced by the authorities and the managers of cultural institutions that are willing to develop the concept of sustainable management in culture, and to build the Polish–Czech cross-border market for cultural services, also include:

- (i)

- language barrier (85% of experts)—ignorance or poor knowledge of the neighbouring country’s language is an important barrier to the full receipt of the offer of some of the neighbour’s cultural institutions (e.g., theatre, cinema, or library),

- (ii)

- lack of information about the cultural offer on the other side of the border (80%),

- (iii)

- the low position of culture in the hierarchy of the needs of the residents of both Cieszyn and Český Těšín (65%),

- (iv)

- chaos in the cultural offers on both sides of the town, the overlapping dates of cultural events (63%),

- (v)

- lack of joint Polish–Czech promotion of the cultural offers (60%),

- (vi)

- lack of interest by the inhabitants of both towns for the culture of the neighbouring country (40%),

- (vii)

- difficulties in developing a cultural offer that is equally appealing to Poles and Czechs (even a very popular theatre actor in Poland may be completely anonymous to the residents of Český Těšín),

- (viii)

- economic barrier—for example, for the residents of Český Těšín, the cultural offer in some Polish cultural institutions (e.g., Adam Mickiewicz Theatre in Cieszyn) is less attractive price-wise than a similar cultural offer that is available on the Czech side of the town,

- (ix)

- psychological barrier—in the consciousness of some residents of Cieszyn and Český Těšín, there is a permanent border dividing the town into two different parts (Polish and Czech).

Therefore, hypothesis H3, assuming that the main barrier that hinders the residents of both Cieszyn and Český Těšín from making use of the cultural offer that is available on the other side of the border is a lack of interest in the cultural offer of the neighbouring country, was not confirmed.

The interviewed experts also pointed to changes in the cultural offer, which in their opinion, could facilitate the implementation of the concept of the sustainable management of the offer of cultural institutions in a town divided by a border, such as Cieszyn and Český Těšín. The vast majority of them (75%) stated that above all, quality should be valued more than quantity, which means that the large number of cultural events being organised (which causes chaos in the cultural offer of the town) should be limited for the benefit of their quality. Moreover, in the experts’ opinion, proper coordination of activities performed on both sides of the town by the Polish and the Czech cultural department in the town is necessary. According to some experts (45%), cultural departments should become more focused on the coordination of activities performed by self-governmental cultural institutions, and should support them in the promotion of the cultural offer on the other side of the border. In the opinion of 55% of experts, town halls should organise panels and meetings with the participation by all of the directors of self-governmental cultural institutions, in order to establish a schedule of cultural events, profile the cultural offer, and determine the common “direction” and the common goals of both a strategic and current (operational) nature. Ideally, such meetings would be organised together with the participation of representatives of self-governmental cultural institutions located in Český Těšín. At the same time, it was noticed that in a town divided by a border, such as Cieszyn and Český Těšín, common Polish–Czech cultural policy is necessary. Such a cultural policy should be one that would last longer than only one electoral period. Town authorities should clearly express what they expect from the cultural institutions. For example, they should determine whether the cultural offer should follow the expectations of the majority of residents and whether it should be more commercial (closer to entertainment) or whether it should be more ambitious and filled with artistic content (which would, however, require greater financial expenses and much more intensive cultural education than before). In the experts’ opinion, the cultural policy in Cieszyn and Český Těšín should be based on the concept of sustainable development in culture, and the understanding that in the common culture of Poland and the Czech Republic, there is something that could be defined as a value-creation chain. At the same time, culture must no longer be seen from the perspective of different sectors; instead, the potential of the cultural institutions of Cieszyn and Český Těšín should be treated as a capital that significantly influences the development of other industries, such as tourism, and which stimulates the socio-economic development of the whole region.

5. Conclusions

The cross-border partnership of local self-governments, i.e., the City of Cieszyn and Český Těšín in the field of culture, presented in the article, is innovative in nature, as it develops intersectoral cooperation between self-governmental organisations, the third sector, or private organisations with different competences, resources, and potentials. At the same time, successful cross-border cultural projects in this area (e.g., the “Two Shores Garden”, the “Cinema on the Border”, the “Three Brothers Day”) confirm that cultural problems are not limited to the sphere of public management, but are also very important for the third sector, i.e., private entities representing the needs and expectations of local communities. The sustainable management of the offers of cultural institutions in a city divided by a border should lead to the gradual improvement of the offer, the professionalisation of culture management, and an improvement of methods and techniques of human resources management for the development of the cultural sector in both cities. Bringing these assumptions to life will lead to an increased interest in the cultural offer, and also the offer that is available on the other side of the border, due to the fact that it will be possible to prepare a cultural offer in the neighbour’s language and to promote it through media that is tailored to different market segments. However, we must remember that due to the independent conditions on the market of cultural services, a cross-border offer (dedicated to the residents of both cities) should be available in cross-border cities, along with an offer that is dedicated only to the city residents in which the cultural institution functions.

Sustainable management of the cultural institutions’ offer in a city divided by a border requires very difficult changes, because they take place in a poorly measurable and strongly individualised area of attitudes and mutual understanding. The development of mutual understanding depends to a large extent on the scope, form, and effectiveness of intersectoral communication, which cannot be limited to individual, semi-formal conversations, the consideration of financial matters, passing on information about decisions taken by the offices of both cities, or arrangements for individual events. Intersectoral consultations should exceed sectoral affiliations and address all issues that are related to local culture, starting with its overall vision. The participation of non-governmental organisations or private cultural entities cannot be limited here to consulting their cooperation with the local government, and therefore only to some of the cultural issues. There is a need to work out a cross-border strategy for the development of the cultural offer, which would exceed, on the one hand, the horizon of a single budget year, and on the other hand—the routine of shaping local culture only by planning specific events.

In summary, analysing the research results presented here, as well as the available source literature, one can point to the priorities for the development of cross-border cooperation in European Union cities belonging to Schengen, which, like Cieszyn and Český Těšín, are divided by a border. These priorities are:

- (i)

- Cross-border cooperation between self-governments, institutions, and other cultural entities in both cities,

- (ii)

- Shared cultural education of the inhabitants of both cities, especially for children and youth,

- (iii)

- Development of the cross-border cultural offer and the improvement of its accessibility for various groups of recipients,

- (iv)

- Creating common cross-border branded products in the field of culture,

- (v)

- Undertaking joint cross-border information and promotion activities that are carried out in a language that is understandable to the inhabitants of both cities.

The aforementioned priorities for the development of cross-border cooperation in the field of culture cover the key areas of activity that should be developed within the organisational and financial capacity of all stakeholder groups who should be involved in the development of the cross-border market for cultural services. The implementation of the indicated priorities will also enable the sustainable management of the cultural institutions’ offers in cross-border cities, which should take place through the following activities:

- (i)

- At various levels (between the self-governments of both cities, between public cultural institutions, non-governmental organisations, and private organisations operating in both cities),

- (ii)

- In various thematic areas (e.g., joint cultural education, joint marketing activities, joint staff training, common bilingual cultural offers, etc.),

- (iii)

- In the formal dimension (e.g., as official contacts between institutions) and in the informal dimension (e.g., contacts of informal groups, non-official relations, social relations, etc.),

- (iv)

- Through better mutual understanding (e.g., learning the language of a neighbour’s country, regular consultative meetings),

- (v)

- By implementing a common cross-border cultural policy (e.g., including similar cultural tasks in the budgets of both cities, joint micro-grants for the development of cross-border cooperation between informal groups and associations).

The presented activities are necessary to create a balanced, diversified, attractive, and diverse cultural offer, corresponding to the authentic cultural needs of the residents of cities that share a state border. With the current, very large, and broadly understood degree of competition in the sphere of culture, only an extremely attractive cultural product is able to induce the public to give up other forms of free time and dedicate it to active participation in culture. However, we should remember that not all cultural projects should have a clearly trans-border dimension. A cross-border cultural offer should be created if its full reception is possible for residents on both sides of the border, and if it is potentially interesting for the inhabitants of both cities.

Author Contributions

Ł.W. designed the research, provided the data collection and drafted the manuscript. Z.D.-P. and B.D. provided extensive suggestion throughout the study regarding the Abstract, Introduction, Methodology, Results and Discusion, and revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the research, cooperated with each other to revise the paper, and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wagemann, M. Sustainable forestry: The basis of future management. Sugar Ind. 2011, 136, 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, W. The development of sustainable forestry in Württemberg—Idea and historical reality. Allgemeine Forst und Jagdzeitung 2014, 185, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Agenda 21 for Culture, Agenda 21 2008. Available online: http://www.agenda21culture.net/sites/default/files/files/documents/multi/ag21_en.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development, UCLG 2010. Available online: http://www.agenda21culture.net/documents/culture-the-fourth-pillar-of-sustainability (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies, UNESCO 2013. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/pdf/final_hangzhou_declaration_english.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Culture 21: Actions—Commitments on the Role of Culture in Sustainable Cities, UCLG 2010. Available online: http://www.worldurbancampaign.org/culture-21-actions-%E2%80%93-commitments-role-culture-sustainable-cities (accessed on 26 August 2018).

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. Opportunities for Cross-Border Entrepreneurship Development in a Cluster Model Exemplified by the Polish–Czech Border Region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E. Cross-border cooperation in Inner Scandinavia: A Territorial Impact Assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 62, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. Assessment of trends for the development of cross border cultural clusters. Forum Sci. Oecon. 2015, 3, 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schenone, C.; Brunenghi, M.M.; Pittaluga, I.; Hajar, A.; Kamali, W.; Montaresi, F.; Rasheed, M.; Wahab, A.A.; El Moghrabi, Y.; Manasrah, R.; et al. Managing European Cross Border Cooperation Projects on Sustainability: A Focus on MESP Project. Sustainability 2017, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, Ł. Application of marketing in cultural organizations: The case of the Polish Cultural and Educational Union in the Czech Republic. Cult. Manag. Sci. Educ. 2017, 1, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. A model of sustainable development of cross-border inter-organizational cooperation, conclusion from the research. In Business Models: Strategies, Impact and Challenges; Jabłoński, A., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepańska-Woszczyna, K. The importance of organizational culture for innovation in the company. Forum Sci. Oecon. 2014, 2, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, Ł. Cultural Management. Strategy and Marketing Aspects; Logos Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sobocińska, M. Management of value for customers on the culture market. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lisiński, M. Structural Analysis of the Management Science Methodology. Bus. Manag. Educ. 2013, 11, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. Pragmatism and the Philosophical Foundations of Mixed Methods Research. In SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, Ch., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, Ł. Websites of Polish cultural and educational organizations in the Czech Republic—Analysis and evaluation. Forum Sci. Oecon. 2015, 3, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J.; Wróblewski, Ł.; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, K. Identification and assessment of barriers to the development of cross-border cooperation. In Innovation Management and Education Excellence through Vision 2020, Proceedings of the 31st International Business Information Management Association Conference, Milano, Italy, 25–26 April 2018; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association: Milan, Italy, 2018; pp. 3317–3327. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J.; Castanho, R.A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M. Cross-border cooperation—The barriers analysis and the recommendations. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 17, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, Ł.; Kurowska-Pysz, J.; Dacko-Pkiewicz, Z. Polish-Czech micro-projects as a tool for shaping consumer behaviour on the cross-border market for cultural services. In Innovation Management and Education Excellence through Vision 2020, Proceedings of the 31st International Business Information Management Association Conference, Milano, Italy, 25–26 April 2018; Soliman, K.S., Ed.; International Business Information Management Association: Milan, Italy, 2018; pp. 3131–3141. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. Partnership Management in Polish-Czech Micro-Projects in Euroregion Beskidy; Economic Policy in the European Union Member Countries; Silesian University: Karvina, Czech Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewski, Ł. The Influence of Creative Industries on the Socioeconomic Development of Regions in Poland. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2014, 2, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, B.; Kramsch, O. (Eds.) Cross-Border Governance in the European Union; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J. The Circumstances of Knowledge Transfer within the Scope of the Cross-Border Czech-Polish Projects 2014–2020. Forum Sci. Oecon. 2015, 3, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho, R.A.; Loures, L.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L. Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) in Southern Europe—An Iberian Case Study. The Eurocity Elvas-Badajoz. Sustainability 2017, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramillano, A.; Levarlet, F.; Nilsson, H.; Camagni, R.; Capello, R.; Caragliu, A.; Fratesi, U.; Lindberg, G. Collecting Solid Evidence to Assess the Needs to Be Addressed by Interreg Cross-Border Cooperation Programmes; Directorate General for Regional and Urban Policy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Appadurai, A. Modernity at Large. Cultural Dimensions of Globalization; University of Minnnesota Press: London, UK; Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Interreg Va Czech Republic—Poland Programme 2014–2020. Available online: https://www.keep.eu/keep/programme/31 (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Anderson, B. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism; Revised Edition; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, S. The Need for Roots: Prelude Towards a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, K. The Global Competitiveness Report 2016–2017; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism; WIN-Gallup International. Available online: https://sidmennt.is/wp-content/uploads/Gallup-International-um-tr%C3%BA-og-tr%C3%BAleysi-2012.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).