Analysis of the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Family Functioning in Adolescents’ Sustainable Use of Alcohol and Tobacco

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Risk and Protection Factors of Using Alcohol and Tobacco

1.2. Study Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Use of Alcohol and Tobacco

3.2. Emotional Intelligence, Resilience and Family Functioning: Relationship with Alcohol and Tobacco Use

3.3. Logistic Regression Model: Alcohol

3.4. Logistic Regression Model: Tobacco

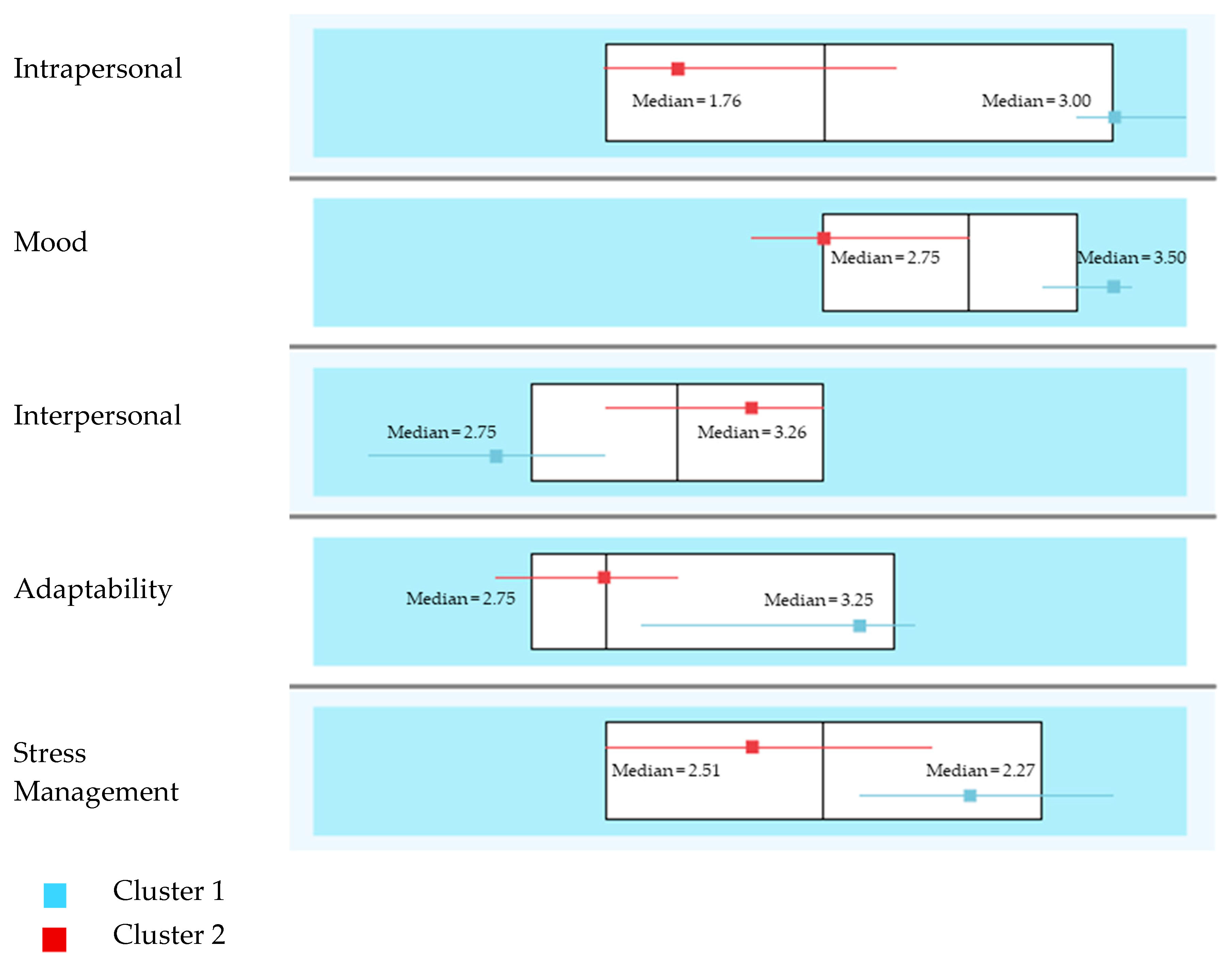

3.5. Emotional Profiles of Drinkers and Differences in Self-Concept

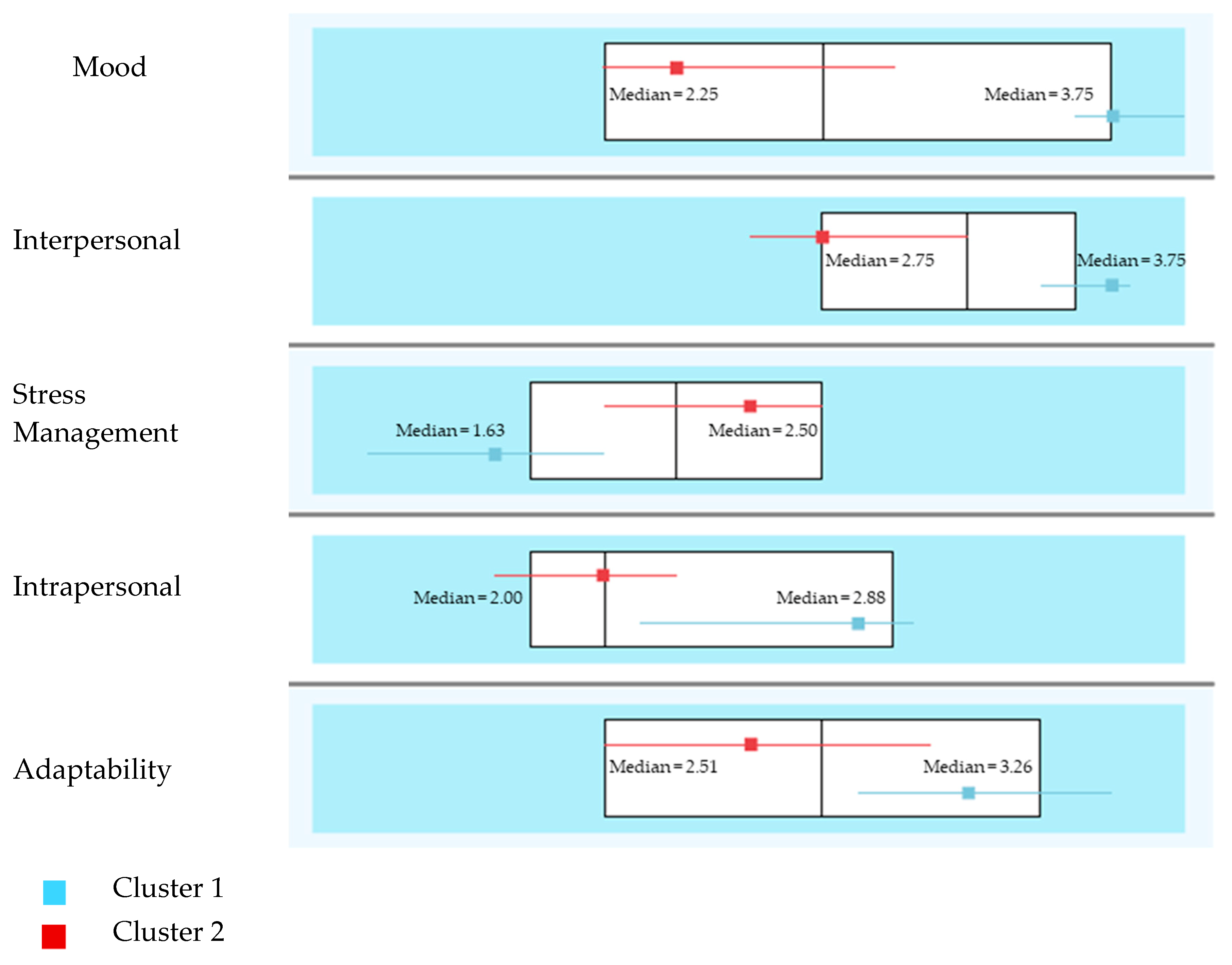

3.6. Emotional Profiles of Smokers and Differences in Self-Concept

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knoll, L.J.; Magis-Weinberg, L.; Speekenbrink, M.; Blakemore, S.J. Social influence on risk perception during adolescence. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 26, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-García, D.; Núñez, J.C.; García, T.; Barreiro-Collazo, A. Individual, Family, and community predictors of cyber-aggression among adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2018, 10, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrín, O.; Gómez-Fraguela, J.A.; Maneiro, L.; Sobral, J. Effects of parenting practices through deviant peers on nonviolent and violent antisocial behaviours in middle- and late-adolescence. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2018, 9, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derlan, C.L.; Umaña-Taylor, A.J. Brief report: Contextual predictors of African American adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity affirmation-belonging and resistance to peer pressure. J. Adolesc. 2015, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Gardner, C.O.; Edwards, A.C.; Dick, D.M.; Hickman, M. Childhood risk factors for heavy episodic alcohol use and alcohol problems in late adolescence: A marginal structural model analysis. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2018, 79, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, K.; Tiiri, E.; Lempinen, L.; Sillanmäki, L.; Kronström, K.; Sourander, A. Time trends of Finnish adolescents’ mental health and use of alcohol and cigarettes from 1998 to 2014. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, J.; O´Loughlin, E.K.; Wellman, R.J.; Sylvestre, M.P.; Dugas, E.N.; Chagnon, M.; McGrath, J.J. Predictors of cigarette smoking initiation in early, middle, and late adolescence. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Encuesta Sobre Uso de Drogas en Enseñanzas Secundarias en España 2016–2017; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, España, 2018.

- Míguez, M.C.; Becoña, E. Do cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption associate with cannabis use and problem gambling among Spanish adolescents? Adicciones 2015, 27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja, G.L.; Lacerda-Santos, J.T.; de Monura, D.; de Souza, I.; Granville-García, A.F.; Caldas, A.F.; Almeida, J. Smoking and alcohol consumption among university students of the healthcare area. J. Public Health 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, T.J.; Forster, M.; Unger, J.B.; Sussman, S. Predictors of alcohol-related negative consequences in adolescents: A systematic review of the literature and implications for future research. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 48, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaete, J.; Araya, R. Individual and contextual factors associated with tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use among Chilean adolescents: A multilevel study. J. Adolesc. 2017, 56, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Loredo, V.; Fernández-Hermida, J.R.; De la Torre-Luque, A.; Fernández-Artamendi, S. Polydrug use trajectories and differences in impulsivity among adolescents. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2018, 18, 189–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusxka, B.; Bácskai, E.; Czobor, P.; Gerevich, J. Physical aggression and concurrent alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 15, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, B.; Portela, I.; López, E.; Domínguez, V. Verbal violence in students of compulsory secondary education. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2018, 8, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, E.; Jiménez, T.I.; Moreno, D. Aggressive behavior in adolescence as a predictor of personal, family, and school adjustment problems. Psicothema 2018, 30, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, J.J.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Barragán, A.B.; Martos, Á.; Sánchez-Marchán, C. Drug use in adolescents in relation to social support and reactive and proactive aggressive behavior. Psicothema 2016, 28, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembo, R.; Briones-Robinson, R.; Barrett, K.; Winters, K.C.; Schmeidler, J.; Ungaro, R.A.; Karas, L.; Belenko, S.; Gulledge, L. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Delinquency Among Truant Youth in a Brief Intervention Project: A Longitudinal Study. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2011, 21, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabina, C.; Schally, J.L.; Marciniec, L. Problematic alcohol and drug use and the risk of partner violence victimization among male and female college students. J. Fam. Violence 2017, 32, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero-Jurado, M.M.; Martos-Martínez, Á.; Barragán-Martín, A.B.; Hernández-Garre, C.M.; Simón-Márquez, M.M.; Gázquez, J.J. Factors influencing or maintaining addictive substance use in Secondary Students. Rev. Psicol. Educ. 2018, 13, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchán, A.; Romero, A.F.; Alameda, J.R. Psychoactive substances consumption, emotional intelligence and academic performance in a university students simple. Rev. Esp. Drogodepend. 2017, 42, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Aranda, D.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Cabello, R.; Extremera, N. Perceived emotional intelligence and adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Ansiedad Estrés 2006, 12, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fainsilber, L.; Stettler, N.; Gurtovenko, K. Traumatic stress symptoms in children exposed to intimate partner violence: The role of parent emotion socialization and children’s emotion regulation abilities. Soc. Dev. 2016, 25, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Best, K.M.; Garmezy, N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Dev. Psychopathol. 1990, 2, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artuch-Garde, R.; González-Torres, M.D.C.; de la Fuente, J.; Vera, M.M.; Fernández-Cabezas, M.; López-García, M. Relationship between resilience and self-regulation: A study of spanish youth at risk of social exclusion. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, J.M.; Núñez-Lozano, J.M.; Goméz-Molinero, R.; Zayas, A.; Guil, R. Emotion Regulation ability and resilience in a sample of adolescents from a suburban area. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizoso-Gómez, C.; Arias-Gundín, O. Resilience, optimism and academic burnout in university students. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 11, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, R.K.; Freund, M.; Bowman, J.; Wolfenden, L.; Gillham, K.; Dray, J.; Wiggers, J. Association between adolescent tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use and individual and environmental resilience protective factors. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzinski, K.; McDonough, P.; Gartner, R.; Strike, C. Is there room for resilience? A scoping review and critique of substance use literature and its utilization of the concept of resilience. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2017, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; García-Moya, I.; Rivera, F.; Ramos, P. Characterization of Vulnerable and Resilient Spanish Adolescents in Their Developmental Contexts. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Becoña, E.; Míguez, M.C.; López, A.; Vázquez, M.J.; Lorenzo, M.C. Resilience and alcohol consumption in young people. Health Addict. 2006, 6, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tsakpinoglou, F.; Poulin, F. Best friends’ interactions and substance use: The role of friend pressure and unsupervised co-deviancy. J. Adolesc. 2017, 60, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M.S.; Tucker, J.S.; Pedersen, E.R.; D’Amico, E.J. Relative influence of perceived peer and family substance use on adolescent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use across middle and high school. Addict. Behav. 2019, 88, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, J.J.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Martos, A.; Cardila, F.; Barragán, A.B.; Carrión, J.J.; Garzón, A.; Mercader, I. Spanish adaptation of the Alcohol Expectancy Adolescent Questionnaire, Brief. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. 2015, 5, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero-Jurado, M.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez-Linares, J.J.; Barragán-Martín, A.B. Analysis and Profiles of Drug Use in Adolescents: Perception of Family Support and Evaluation of Consequences. Aten. Fam. 2017, 24, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbeater, B.; Sukhawathanakul, P.; Smith, D.; Bowen, F. Reciprocal associations between interpersonal and values dimensions of school climate and peer victimization in elementary school children. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riquelme, M.; García, O.F.; Serra, E. Psychosocial maladjustment in adolescence: Parental socialization, self-esteem, and substance use. An Psicol. 2018, 34, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Guerrero, T.J.; Vázquez-Cruz, E.; Córdova-Soriano, J.A. Perception of Family Functionality and Alcohol Use in Adolescents. Aten. Fam. 2016, 23, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohannessian, C.M.; Flannery, K.M.; Simpson, E.; Russell, B.S. Family functioning and adolescent alcohol use: A moderated mediation analysis. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambron, C.; Kosterman, R.; Catalano, R.F.; Guttmannova, K.; Hawkins, J.D. Neighborhood, family, and peer factors associated with early adolescent smoking and alcohol use. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita, F.; Álvaro, J.I. Effect of snuff and alcohol on academics and family factors in adolescent. Health Addict. 2014, 14, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chacón, R.; Zurita, F.; Castro, M.; Espejo, T.; Martínez, A.; Ruiz-Rico, G. The association of self-concept with substance abuse and problematic use of video games in university students: A structural equation model. Adicciones 2018, 30, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro, J.I.; Zurita, F.; Castro, M.; Martínez, A.; García, S. The relationship between consumption of tobacco and alcohol and self-concept in Spanish adolescents. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2016, 27, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezquita, L.; Stewart, S.; Kuntshe, E.; Grant, V. Cross-cultural examination of the five-factor model of drinking motives in Spanish and Canadian undergraduates. Adicciones 2016, 28, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón, R.; Castro, M.; Caracuel, R.; Padial, R.; Collado, D.; Zurita, F. Profiles of alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents from Andalusia in the first cycle of secondary education. Health Addict. 2016, 16, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Barragán, A.B.; Gázquez, J.J. Profiles of violence and alcohol and tobacco use in relation to impulsivity: Sustainable consumption in adolescents. Sustainability 2019, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, R. The Connection Between Academic Failure and Adolescent Drinking in Secondary School. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 79, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvanko, A.R.; Strickland, J.C.; Slone, S.A.; Shelton, B.J.; Reynolds, A. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: Predicting contingency management treatment outcomes for adolescent smokers. Addict. Behav. 2019, 90, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. La División Del Trabajo Social; Planeta-Agostini: Barcelona, España, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, C.T.; Lee, J.; Menon, T.; Im, D.K. Cheater´s hide and seek: Strategic cognitive network activation during ethical decision making. Soc. Netw. 2019, 58, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenqvist, E. Two Functions of Peer Influence on Upper-secondary Education Application Behavior. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 91, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Bar-On, R.; Parker, J.D.A. Emotional Quotient Inventory: Youth Version (EQ-i:YV): Technical Manual; MultiHealth Systems: Toronto, NT, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez, J.J.; Mercader, I.; Molero, M.M. Brief Emotional Intelligence Inventory for Senior Citizens (EQ-i-M20). Psicothema 2014, 26, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrándiz, C.; Hernández, D.; Bermejo, R.; Ferrando, M.; Sáinz, M. Social and Emotional Intelligence in Childhood and Adolescence: Spanish Validation of a Measurement Instrument. Rev. Psicodidact. 2012, 17, 309–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvalcaba-Romero, N.A.; Gallegos-Guajardo, J.; Villegas-Guinea, D. Validation of the resilience scale for adolescents (READ) in Mexico. J. Behav. Health Soc. Issues 2015, 6, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjemdal, O.; Friborg, O.; Stiles, T.C.; Martinussen, M.; Rosenvinge, J. A new scale for adolescents’ resilience: Grasping the central protective resources behind healthy development. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2006, 39, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellón, J.A.; Delgado, A.; Luna, J.D.; Lardelli, P. Validity and reliability of the Apgar-family questionnaire on family function. Aten. Prim. 1996, 18, 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein, G.; Ashworth, C.; Montano, D. Validity and reliability of the Family APGAR as a test of family function. J. Fam. Pract. 1982, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, L.A.R.; Katz, B.; Colby, S.M.; Barnett, N.P.; Golembeske, C.; Lebeau-Craven, R.; Monti, P.M. Validity and Reliability of the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire Adolescent, Brief. J. Child. Adolesc. Subst. Abus. 2007, 16, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.; Musitu, G. AF5: Autoconcepto Forma 5; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, España, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bretón, S.; Zurita, F.; Cepero, M. Analysis of the levels of self-concept and resilience, in the high school basketball players. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2017, 26, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, F.M. Relationships between coping with daily stress, self-concept, social skills and emotional intelligence. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behav. Res. Methods 2006, 38, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Lara, S. Fiabilidad y alfa ordinal. Actas Urol. Esp. 2018, 42, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua, P.; Zumbo, B.D. Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada. Psicothema 2008, 20, 896–901. [Google Scholar]

- Claes, M.; Lacourse, E.; Ercolani, A.; Pierro, A.; Leone, L.; Presaghi, F. Parenting, Peer Orientation, Drug Use, and Antisocial Behavior in Late Adolescence: A Cross-National Study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2005, 34, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Pérez, J.J.; Pérez-Cosín, J.V.; Perpiñán, S. El proceso de socialización de los adolescentes postmodernos: Entre la inclusión y el riesgo. Recomendaciones para una ciudadanía sostenible. Pedagogía Social. Rev. Interuniv. 2015, 25, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennis, J.; Stahler, G.J.; Mason, M.J. Risky Substance Use Environments and Addiction: A New Frontier for Environmental Justice Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | β | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(β) | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | −0.454 | 0.199 | 5.208 | 1 | 0.022 | 1.574 | 1.066–2.325 |

| Interpersonal | −0.032 | 0.259 | 0.015 | 1 | 0.902 | 0.969 | 0.583–1.609 |

| Stress Management | −0.182 | 0.163 | 1.261 | 1 | 0.262 | 0.833 | 0.606–1.146 |

| Adaptability | 0.199 | 0.184 | 1.170 | 1 | 0.279 | 1.221 | 0.851–1.752 |

| Mood | −0.040 | 0.206 | 0.037 | 1 | 0.847 | 0.961 | 0.641–1.440 |

| Family Cohesion | −0.350 | 0.232 | 2.276 | 1 | 0.131 | 0.705 | 0.447–1.110 |

| Family Competence | −0.113 | 0.231 | 0.239 | 1 | 0.625 | 0.893 | 0.568–1.404 |

| Social Competence | 0.293 | 0.194 | 2.280 | 1 | 0.131 | 1.340 | 0.916–1.960 |

| Social Resources | 0.184 | 0.229 | 0.642 | 1 | 0.423 | 1.202 | 0.767–1.883 |

| Orientation toward Goals | −0.207 | 0.216 | 0.916 | 1 | 0.339 | 0.813 | 0.533–1.242 |

| Family Functioning | −0.017 | 0.074 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.822 | 0.984 | 0.851–1.137 |

| Positive Expectancies | 0.795 | 0.182 | 19.160 | 1 | 0.000 | 2.215 | 1.551–3.162 |

| Negative Expectancies | 0.295 | 0.179 | 2.714 | 1 | 0.099 | 1.344 | 0.946–1.910 |

| Constant | −3.274 | 1.254 | 6.816 | 1 | 0.009 | 0.038 |

| Variables | β | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(β) | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | 0.215 | 0.258 | 0.698 | 1 | 0.404 | 1.240 | 0.749–2.054 |

| Interpersonal | 0.355 | 0.357 | 0.990 | 1 | 0.320 | 1.426 | 0.709–2.869 |

| Stress Management | −0.716 | 0.245 | 8.510 | 1 | 0.004 | 0.489 | 0.302–0.791 |

| Adaptability | −0.005 | 0.286 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.986 | 0.995 | 0.568–1.744 |

| Mood | −0.189 | 0.276 | 0.470 | 1 | 0.493 | 0.828 | 0.482–1.422 |

| Family Cohesion | −0.715 | 0.294 | 5.920 | 1 | 0.015 | 0.489 | 0.275–0.870 |

| Family Competence | 0.196 | 0.311 | 0.399 | 1 | 0.528 | 1.217 | 0.662–2.237 |

| Social Competence | 0.057 | 0.274 | 0.043 | 1 | 0.836 | 1.058 | 0.619–1.810 |

| Social Resources | 0.512 | 0.317 | 2.603 | 1 | 0.107 | 1.668 | 0.896–3.107 |

| Orientation toward Goals | −0.331 | 0.294 | 1.268 | 1 | 0.260 | 0.719 | 0.404–1.277 |

| Family Functioning | −0.073 | 0.099 | 0.542 | 1 | 0.462 | 0.930 | 0.765–1.129 |

| Constant | 0.236 | 1.471 | 0.026 | 1 | 0.873 | 1.266 |

| Total Sample of Drinkers (N = 119) | Cluster | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 45) | 2 (n = 74) | ||

| Intrapersonal | M = 2.25 (SD = 0.76) | M = 2.96 (SD = 0.50) | M = 1.82 (SD = 0.54) |

| Interpersonal | M = 2.98 (SD = 0.62) | M = 3.30 (SD = 0.42) | M = 2.79 (SD = 0.64) |

| Stress management | M = 2.45 (SD = 0.95) | M = 2.40 (SD = 1.30) | M = 2.47 (SD = 0.67) |

| Adaptability | M = 2.86 (SD = 0.62) | M = 3.10 (SD = 0.55) | M = 2.71 (SD = 0.61) |

| Mood | M = 2.99 (SD = 0.78) | M = 3.45 (SD = 0.51) | M = 2.71 (SD = 0.79) |

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | t | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |||

| Academic Self-Concept | 45 | 3.48 | 0.75 | 74 | 3.06 | 0.78 | 2.88 ** | 0.005 |

| Social Self-Concept | 45 | 3.77 | 0.44 | 74 | 3.36 | 0.48 | 4.66 *** | 0.000 |

| Emotional Self-Concept | 45 | 3.41 | 0.71 | 74 | 3.09 | 0.66 | 2.46 * | 0.015 |

| Family Self-Concept | 45 | 3.87 | 0.83 | 74 | 3.39 | 0.53 | 3.82 *** | 0.000 |

| Physical Self-Concept | 45 | 3.57 | 0.83 | 74 | 3.27 | 0.87 | 1.84 | 0.067 |

| Total Sample of Smokers (N = 39) | Cluster | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 12) | 2 (n = 27) | ||

| Intrapersonal | M = 2.23 (SD = 0.82) | M = 2.67 (SD = 0.92) | M = 2.04 (SD = 0.71) |

| Interpersonal | M = 3.07 (SD = 0.67) | M = 3.67 (SD = 0.30) | M = 2.80 (SD = 0.62) |

| Stress Management | M = 2.22 (SD = 0.72) | M = 1.67 (SD = 0.63) | M = 2.46 (SD = 0.62) |

| Adaptability | M = 2.80 (SD = 0.78) | M = 3.17 (SD = 0.70) | M = 2.64 (SD = 0.77) |

| Mood | M = 2.85 (SD = 0.89) | M = 3.71 (SD = 0.35) | M = 2.46 (SD = 0.79) |

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | t | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |||

| Academic Self-Concept | 12 | 3.39 | 0.78 | 27 | 2.70 | 0.69 | 2.75 ** | 0.009 |

| Social Self-Concept | 12 | 3.83 | 0.40 | 27 | 3.34 | 0.50 | 3.00 ** | 0.005 |

| Emotional Self-Concept | 12 | 3.64 | 0.67 | 27 | 3.09 | 0.84 | 1.98 | 0.054 |

| Family Self-Concept | 12 | 3.79 | 0.56 | 27 | 3.31 | 0.66 | 2.20 * | 0.034 |

| Physical Self-Concept | 12 | 3.76 | 0.72 | 27 | 2.89 | 0.80 | 3.22 ** | 0.003 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molero Jurado, M.d.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.d.C.; Barragán Martín, A.B.; del Pino Salvador, R.M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Analysis of the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Family Functioning in Adolescents’ Sustainable Use of Alcohol and Tobacco. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102954

Molero Jurado MdM, Pérez-Fuentes MdC, Barragán Martín AB, del Pino Salvador RM, Gázquez Linares JJ. Analysis of the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Family Functioning in Adolescents’ Sustainable Use of Alcohol and Tobacco. Sustainability. 2019; 11(10):2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102954

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolero Jurado, María del Mar, María del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes, Ana Belén Barragán Martín, Rosa María del Pino Salvador, and José Jesús Gázquez Linares. 2019. "Analysis of the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Family Functioning in Adolescents’ Sustainable Use of Alcohol and Tobacco" Sustainability 11, no. 10: 2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102954

APA StyleMolero Jurado, M. d. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. d. C., Barragán Martín, A. B., del Pino Salvador, R. M., & Gázquez Linares, J. J. (2019). Analysis of the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Family Functioning in Adolescents’ Sustainable Use of Alcohol and Tobacco. Sustainability, 11(10), 2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102954