Factors Associated with Travel Behavior of Millennials and Older Adults: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Background

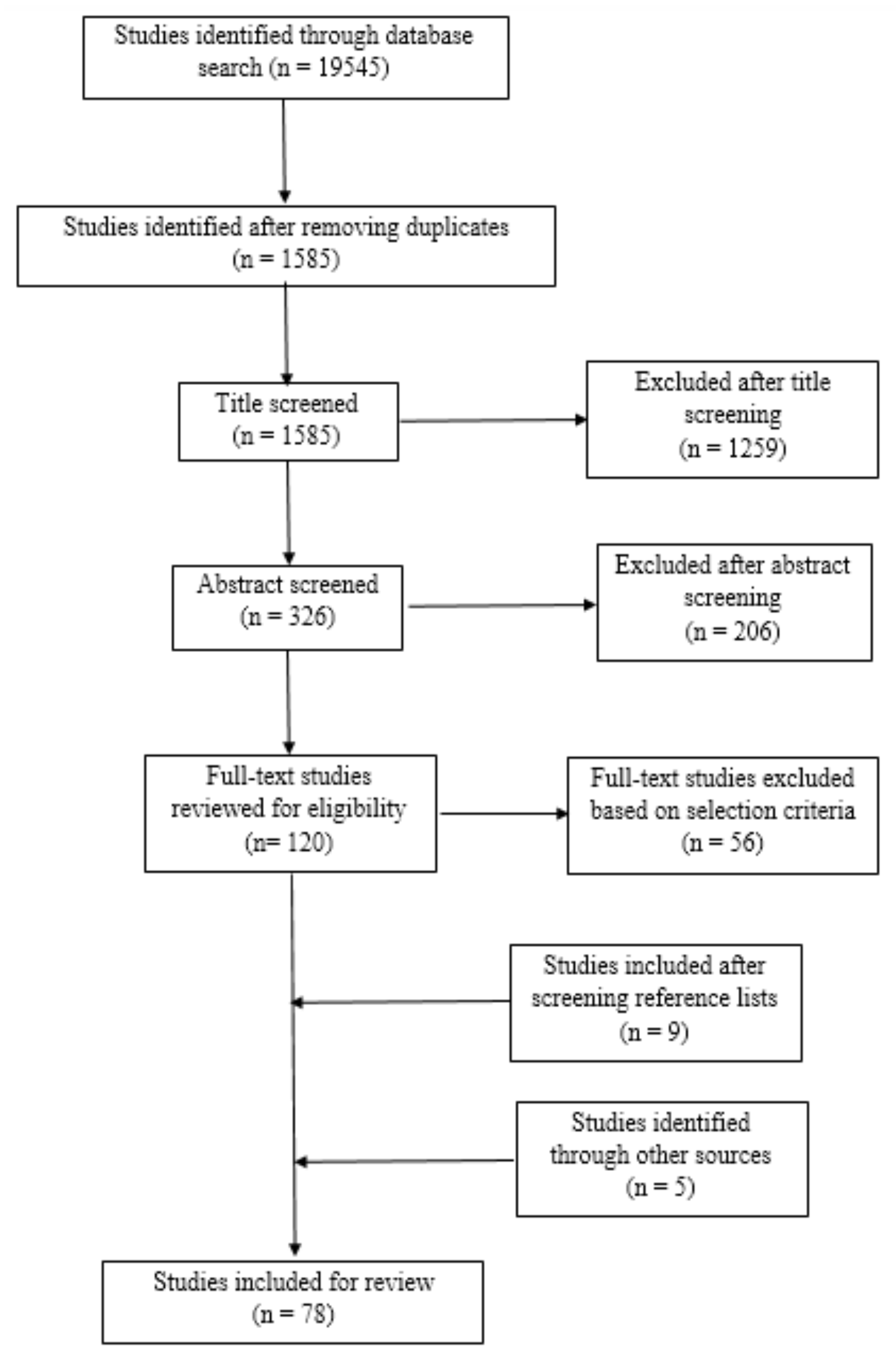

2. Methods

- English language studies.

- Travel-behavior-related studies that either considered generational differences or focused on a specific generation (baby boomers/seniors/older adults, millennials/young adults).

- Studies where the age of the sample population is 16 years or over.

- Studies that considered attributes of daily travel behavior—specifically, mode choice; trip distance; trip frequency; use of alternative transport; ridesharing; and mobility tool ownership: driver’s license, car, bike, transit pass.

- The studies were conducted in developed countries.

- Studies that focused on the travel behavior of the overall population.

- Tourism-related studies, long-distance travel, maritime travel, air travel, and railway travel.

- Studies related to generation-specific travel-support smartphone application development and the use of automotive or electric vehicles.

- Accident-, injury-, and fatality-related researches.

- Studies that focused on health conditions, health-related attributes, and/or physical activity.

3. Types of the Reviewed Literature

4. Travel Trends Among the Two Generations

5. Factors Associated with the Travel Behavior of the Two Generations

5.1. Personal Attributes

5.2. Geography and the Built Environment

5.3. Living Arrangements and Family Life

5.4. Technology Adoption

5.5. Attitudes Towards and Perceptions of Travel Options and Environment

6. Future Research Prospects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Transport Research Part A: Policy and Practice

- Transport Research Part C: Emerging Technologies

- Transportation

- Travel Behavior and Society

- Journal of Transport Geography

- Transportation Research Record

- Journal of Transport and Land Use

- Transport Reviews

- Transport Policy

| Reviewed Study | Document Type | Data Used | Method | Country of the Study | Age Group Considered | Focused Topic/Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahern and Hine (2012) [13] | Journal paper | Qualitative | Focus group | UK | 65 and over | Car use among older adults, Use of community transport service, type of trips/trip purpose |

| Alemi et al. (2018) [59] | Journal paper | California Millennials Dataset 2015 | Descriptive, binary logit model | US | Millennials: 18– 34; Generation X: 35–50 | Adoption of on-demand ride services among millennials and generation X |

| Axhausen (2013) [71] | Report | Quantitative, multiple data sources | Descriptive analysis | Germany and Britain | Born in 80s and 90s | Automobile ownership, licensing, mileage |

| Bailey et al. (2015) [51] | Report | Quantitative, online survey, licensing data by VicRoads | Descriptive analysis | Australia | 18–29 | Reasons behind not holding a driving license |

| Bardazzi and Pazienza (2018) [44] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Household Budget Survey 1997–2013, Panel data | Tobit model | Italy | Different cohorts | Lifecycle and generational effects on transport-related energy use, dependent variables— Choosing private transport, and level of fuel expenditure per adult |

| Barnes et al. (2016) [83] | Journal paper | Quantitative, CCHS (Canadian Community Health Survey) Healthy Aging Cycle (2008/2009) | Logistic regression | Canada | 45 and over | Association between walk score, transit score, transit use, transport walking—whether associations differ across age groups and retirement status |

| Berg et al. (2014) [17] | Journal paper | Qualitative (case studies) and travel diaries | Content analysis | Sweden | 61–67 | After transition to retirement, how mobility is influenced by individual, social, and geographical contexts |

| Berrington and Mikolai (2014) [55] | Report | Quantitative, UK household study | Descriptive analysis, regression analysis | UK | 17–34 | Young adults’ license holding, driving mileage |

| Blumenberg et al. (2012) [24] | Report | Quantitative, National Household Travel Surveys | Descriptive, structural equiation model | US | 15–26 | Travel behavior of young adults—pseudo cohorts |

| Blumenberg et al. (2015) [33] | Report | Quantitative, National Household Travel Surveys | Descriptive, factor analysis, cluster analysis | US | 20–34 | Millennials’ travel behavior at different geographic settings |

| Blumenberg et al. (2016) [76] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 1990 Nationwide Personal Travel Survey, 2001 and 2009 National Household Data | Descriptive, multi-variate model | US | Different age groups | Factors behind young adults’ decline in travel |

| Böcker et al. (2017) [37] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Travel diary of six days | Zero inflated negative binomial regression models, multinomial logit model | Netherland | 65 and over | Seniors’ and non-seniors’ trip frequency and mode choice |

| Boschmann and Brady (2013) [38] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2009 Travel Count Survey | Descriptive, logistic and OLS (Ordinary least squares) regression | US | 60 and over | Seniors’ travel behavior-trips, mode choice, distance, purpose |

| Brown et al. (2016) [58] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2001 and 2009 NHTS—cross-sectional dataset | Descriptive, regression analysis | US | Different birth cohorts | Transit use among youth |

| Buehler and Nobis, 2010 [4] | Conference paper | Quantitative, national travel surveys 1982/83 and 2001/02—cohort analysis | Descriptive, logistics regression | US and Germany | 65 and over | Car use among elderly |

| Busch-Geertsema and Lanzendorf (2017) [22] | Journal paper | Quantitative, online three-wave panel study | Descritive, binary logit | Germany | University students | Mode choice behavior of millennials |

| Buys et al. (2012) [5] | Journal paper | Qualitative and quantitative | Thematic approach | Australia | 55 and over | Transit and car dependency of older adults |

| Circella et al. (2017) [52] | Conference paper | Quantitative, California Millennials Dataset | Descriptive | US | 18–34 | Millennials’ travel behavior |

| Corran et al. (2018) [46] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Logistic regression | UK | Different age groups | Factors influencing elderly people’s non-travel |

| Davis et al. (2012) [50] | Report | Quantitative, National Household Travel Survey 2001 and 2009 | Descriptive analysis | USA | 16–34 | Decline in driving among young adults |

| De Paepe et al. (2018) [79] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Hierarchical logistic regression | Belgium | University students | Mode choice for particular activities |

| Delbosc and Currie (2013) [73] | Journal paper | Quantitative, travel survey data 1994, 1999, 2007, and 2009 | Descriptive analysis, binary logistic regression | Australia | 18–30 | License holding of young adults |

| Delbosc and Currie (2014) [16] | Journal paper | Qualitative | Online focus group | Australia | 17–23 | Attitudes toward cars and licensing |

| Delbosc and Nakanishi (2017) [18] | Journal paper | Qualitative | Semi-structured interview | Australia | 18–30 | Interaction between life course and mobility preference, and attitudes toward cars of millennials |

| Fatmi and Habib (2016) [31] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2006 Transportation Tomorrow Survey | Latent segmentation-based logit model | Canada | 65 and over | Ownership of multiple mobility tools— segments based on frequent trip makers and non-trip makers |

| Fatmi et al. (2014) [32] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2006 Transportation Tomorrow Survey | Latent class logit model | Canada | 17–19 | Mobility tool ownership among youths |

| Figueroa et al. (2014) [81] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Danish National Travel Survey 2006-2011 | Probit model, ordinary least square model | Denmark | Different age groups | How built environment is correlated with the travel patterns of different generations |

| Fordham et al. (2017) [25] | Journal paper | Quantitative, O-D survey 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013 | Pseudocohort analysis | Canada | 50 and over | Public transit use among seniors |

| Giesel and Kohler (2015) [62] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Mobility in Germany 2008 survey | Logistic regression, descriptive analysis | Germany | 65 and over | Elderly people’s daily travel, factors influencing daily short-distance travel (traveling locally) |

| Habib (2015) [40] | Journal paper | Quantitative, NCR’s 2011 Household Travel Survey | Utility theoretic joint model | Canada | 65 and over | Mode choice and travel distance of older people |

| Habib (2018) [29] | Journal paper | Quantitative, travel survey of four universities in GTA | Hazard-based duration model | Canada | University students | Age of acquiring driving license, choice of not acquiring a driving license |

| Habib et al. (2018) [53] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2015 travel survey of four universities in GTA | Cross-nested logit model | Canada | University students | Choice of owning basic mobility tools (driver’s license, car, transit pass, bike) or combination of basic tools |

| Hanson and Hildebrand (2011) [60] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional | Descriptive analysis | Canada | 54–92 | Can rural drivers meet their travel needs without a car? |

| Haustein (2011) [36] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Linear and ordinal regression analysis, cluster analysis | Germany | 60 and over | Older adults’ mobility by different segments |

| Haustein and Siren (2014) [45] | Journal paper | Quantitative, telephone survey of 863 individuals | Descriptive analysis, ordinal regression | Denmark | Born in 1939/40 | Amount of unmet mobility needs—used different segments of drivers. |

| Hess (2011) [80] | Journal paper | Quantitative | Descriptive analysis | US | 60 and over | How perception of distance to bus stops influence walking to bus stops among older adults |

| Hjorthol (2012) [43] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Norwegian nationwide survey of activities and daily mobilities, 2010 | Descriptive, logistic regression | Norway | 67 and over | Older adults’ mobility needs |

| Hjorthol (2016) [70] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Norwegian National Travel Survey data from 1985 to 2009, cross-sectional | Logistic regression, cohort analysis | Norway | 18–25 | Holding a driving license, access to a car |

| Hjorthol et al. (2010) [65] | Journal paper | Quantitative, National Travel Survey from 1984 to 2006, cross-sectional | Cohort analysis | Norway, Sweden, Denmark | 40–84 | Holding a driving license, access to a car |

| Jones et al. (2018) [63] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional data, longitudinal research on aging drivers cohort study | Logistic regression | US | 65–79 | Driving distance by different modes, number of alternate transport sources rather than self-driving among older drivers |

| Klein and Smart (2017) [23] | Journal paper | Quantitative, panel study, panel study of income dynamics | Poission panel regression: random effect model, fixed effects model | US | Born in 80s and 90s | Car ownership, car access |

| Kroesen and Handy (2015) [85] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional, LISS (Longitudinal Internet studies for the Social Sciences) panel data—used 2013 data | Linear regression | Denmark | 30 or younger, and above 30 | Attitudes toward car, attitudes toward public transport |

| Kuhnimhof et al. (2011) [48] | Journal paper | Quantitative, National Travel Survey from 1970 to 2013, cross-sectional | Descriptive analysis | Germany and Britain | Young population of different birth cohorts | Car ownership, distance, multimodality |

| Kuhnimhof et al. (2012) [54] | Journal paper | Quantitative, German Mobility Panel, German Income and Expenditure Survey for 1998 and 2008, time series data | Logistic regression, descriptive analysis | Germany | 18–34 | Car ownership, driving distance |

| Kuhnimhof et al. (2012) [78] | Journal paper | Quantitative, National Travel Survey | Descriptive analysis | Germany, France, Britain, Japan, Norway, US | 17–29 of different decades | Driver’s license, car ownership, distance |

| Kuhnimhof et al. (2012) [49] | Journal paper | Quantitative, National Travel Survey, 2002 and 2008 | Descriptive analysis, multilevel regression | Germany | 18–29 | Driver’s license, car ownership, distance |

| Lavieri et al. (2017) [3] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2014 Mobility Attitudes Survey, cross-sectional | Structural equation model | US | 18–33 | Mode of transport, driver’s license holding, vehicle ownership |

| Le Vine and Polak (2014) [74] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2010 British national travel Surveys | Logistic regression | UK | 17–29 | License holding |

| Leistner and Steiner (2017) [66] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional data | Descriptive | US | 60 and over | Older adults’ dynamic ridesharing—ridesharing has the potential to increase mobility and accessibility |

| Licaj et al. (2012) [75] | Journal Paper | Quantitative, 2005 -2006 Household Travel Survey | Logistics regression | France | 16–24 | Relationship between driving and socio-economic and geographical factors |

| Mattson (2012) [34] | Report | Quantitative, National Travel Survey of 2001 and 2010 | Binary logit model, negative binomial logit model, cluster analysis | US | 65 and over | Frequency of driving and number of trips |

| McDonald (2015) [2] | Journal paper | Quantitative, NTS of multiple years | Regression analysis, descriptive analysis | US | 19–42 | Daily automobile mileage |

| Melia et al. (2018) [84] | Journal paper | Quantitative, NTS 2001 and 2011 | Regression analysis— fractional logit model | UK | 16–34 | Driving frequency, public transport use frequency |

| Mifsud et al. (2017) [39] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Descriptive, regression analysis | Malta | 60 and over | Status of driving, public transport use |

| Mollenkopf et al. (2011) [21] | Journal paper | Mixed method—quantitative and qualitative, longitudinal study—1995, 2000, 2005 | Descriptive analysis, semi-structured interview, content analysis | Germany | 55 or over | Older adults’ perceptions of out-of-home mobility |

| Moniruzzaman et al. (2013) [28] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Montreal’s Household Travel Survey 2008 | Joint discrete-continuous model, hazard based model | Canada | 55 and over | Mode choice—walking, transit; trip length—car, walking, transit |

| Muromachi (2017) [72] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Ordered probit model, descriptive analysis | Japan | 18–26, university students | Intention to purchase a car in future, |

| Nash and Mitra (2018) [30] | Conference paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional, segmentation | Latent class logit model | Canada | University students | University students’ travel behavior including attitudes, and lifestyle |

| Newbold and Scott (2017) [26] | Journal paper | Quantitative, General Social Survey 1998, 2005, 2010 | Descriptive analysis | Canada | Different cohorts | Licensure rate, mode choice |

| Newbold and Scott (2018) [27] | Journal paper | Quantitative, General Social Survey 1998, 2005, 2010 | Descriptive analysis, logistic regression | Canada | Different cohorts | Mode choice, determinants of transit use |

| Rahman et al. (2016) [41] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional, nationwide survey | Descriptive analysis, ordered logit model | US | 65 or over | Older adults’ alternative transportation preferences |

| Sakaria and Stehfest (2013) [19] | Report | Qualitative (telephone survey) and quantitative (online survey) | Descriptive | US | 18–34 | Millennials’ lifestyle, attitudes and decision-making process related to daily travel |

| Schoettle and Sivak (2014) [77] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Descriptive analysis | US | 18–39 | Drivers’ licensing |

| Simons et al. (2014) [15] | Journal paper | Qualitative | Focus group study, content analysis | Belgium | 18–25 | Factors affecting transport mode for short distance travel- focus is given on cycling |

| Simons et al. (2017) [57] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Zero inflated negative binomial regression models | Belgium | 18–25 | Mode choice by different groups of young adults |

| Siren and Haustein (2013) [35] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Cluster analysis, descriptive analysis | Denmark | Born in 1946 and 1947 | Travel habits, expectations and preferences |

| Siren and Haustein (2015) [69] | Journal paper | Quantitative, longitudinal survey. 2009 and follow-up survey in 2012 | Descriptive analysis | Denmark | Born in 1946 and 1947 | How retirement affects baby boomers’ travel—distinguished by ’still working’, ’early retirees’, ‘recent retirees’ |

| Sivak and Schoettle (2011) [56] | Journal paper | Quantitative, Federal Highway Administration on driver’s licenses, 1983 -2008 | Descriptive analysis | US | Different age groups | Driving license holding by age |

| Truong and Somenahalli (2011) [20] | Journal paper | Qualitative and quantitative, cross-sectional travel survey 2010 | Descriptive analysis | Australia | 65 and over | Daily trips, distance travelled, trip chain complexity |

| Truong and Somenahalli (2015) [42] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey 2010 | Multinomial logistic regression | Australia | 65 and over | Factors influencing frequency of using transit |

| Tuokko et al. (2014) [86] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional data, Canadian Driving Research Initiative for Vehicular Safety in Elder (Candrive II) | Descriptive analysis | Canada | 70 and over | Attitudes relevant to driving restriction |

| Turner et al. (2017) [68] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional, nationwide survey 2013 | Multivariate analysis | US | 60 and over | Perceived alternative transport needs by older adults—driving groups vs. non-driving groups |

| Vale et al. (2018) [47] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey 2015 | Descriptive analysis, spatial analysis | Portugal | University students | Commute mode |

| Van Cauwenberg et al. (2013) [82] | Journal paper | Quantitative, cross-sectional | Multilevel logistic regression | Belgium | 60 or over | How physical environmental factors influence older adults’ walking—amount of daily walking |

| Vivoda et al. (2018) [67] | Journal paper | Quantitative | Regression analysis | US | 65 and over | E-hail/ridesharing knowledge, use and level of reliance of older adults |

| Ward et al. (2013) [14] | Journal paper | Qualitative | Focus group | UK | 65 and over | Older adults’ car use |

| Yang et al. (2018) [64] | Journal paper | Quantitative, 2009 National Travel Survey | Linear regression, Logistic regression | US | 65 and over | Active travel trips, public transportation trips, travel purpose, distance travelled |

| Zmud et al. (2017) [61] | Report | Quantitative, multiple data sources | Descriptive analysis | Germany, US, UK, China, Japan | 65 and over | Older adults’ mobility patterns |

References

- Thakuriah, P.V.; Menchu, S.; Tang, L. Car ownership among young adults. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2156, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.C. Are millennials really the “go-nowhere” generation? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavieri, P.S.; Garikapati, V.M.; Bhat, C.R.; Pendyala, R.M. Investigation of heterogeneity in vehicle ownership and usage for the millennial generation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2664, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buehler, R.; Nobis, C. Travel behavior in aging societies. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2182, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, L.; Snow, S.; van Megen, K.; Miller, E. Transportation behaviors of older adults: An investigation into car dependency in urban Australia. Australas J. Ageing 2012, 31, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Circella, G.; Tiedeman, K.; Handy, S.; Alemi, F.; Mokhtarian, P.L. What Affects U.S. Passenger Travel? Current Trends and Future Perspectives? White Paper from the National Center for Sustainable Transportation; University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, H.; de Bell, S.; Flemming, K.; Sowden, A.; White, P.; Wright, K. The experiences of everyday travel for older people in rural areas: A systematic review of UK qualitative studies. J. Transp. Health 2018, 11, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiu, C.; Tight, M.; Burrow, M. The unmet travel needs of the older population: A review of the literature. Transp. Rev. 2016, 37, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Siren, A. Older people’s mobility: Segments, factors, trends. Transp. Rev. 2015, 35, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delbosc, A.; Currie, G. Causes of youth licensing decline: A synthesis of evidence. Transp. Rev. 2013, 33, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.L.; Nixon, S.A. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahern, A.; Hine, J. Rural transport—Valuing the mobility of older people. Res. Transp. Econ. 2012, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.R.M.; Somerville, P.; Bosworth, G. ‘Now without my car I don’t know what I’d do’: The transportation needs of older people in rural Lincolnshire. Local Econ. 2013, 28, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simons, D.; Clarys, P.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I.; de Geus, B.; Vandelanotte, C.; Deforche, B. Why do young adults choose different transport modes? A focus group study. Transp. Policy 2014, 36, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbosc, A.; Currie, G. Using discussion forums to explore attitudes toward cars and licensing among young Australians. Transp. Policy 2014, 31, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Levin, L.; Abramsson, M.; Hagberg, J.E. Mobility in the transition to retirement—The intertwining of transportation and everyday projects. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 38, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbosc, A.; Nakanishi, H. A life course perspective on the travel of Australian millennials. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2017, 104, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaria, N.; Stehfest, N. Millennials and Mobility: Understanding the Millennial Mindset and New Opportunities for Transit Providers (No. Task 17, TCRP Project J-11); American Public Transportation Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, L.T.; Somenahalli, S. Exploring mobility of older people: A case study of Adelaide. In Proceedings of the 34th Australasian Transport Research Forum, Adelaide, Australia, 28–30 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf, H.; Hieber, A.; Wahl, H.-W. Continuity and change in older adults’ perceptions of out-of-home mobility over ten years: A qualitative–quantitative approach. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 782–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch-Geertsema, A.; Lanzendorf, M. From university to work life—Jumping behind the wheel? Explaining mode change of students making the transition to professional life. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2017, 106, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N.J.; Smart, M.J. Millennials and car ownership: Less money, fewer cars. Transp. Policy 2017, 53, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blumenberg, E.; Taylor, B.D.; Smart, M.; Ralph, K.; Wander, M.; Brumbagh, S. What’s Youth Got to Do with It? Exploring the Travel Behavior of Teens and Young Adults; University of California Transportation Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham, L.; Grisé, E.; El-Geneidy, A. When I’m 64: Assessing generational differences in public transit use of seniors in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2651, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, K.B.; Scott, D.M. Driving over the life course: The automobility of Canada’s millennial, generation x, baby boomer and greatest generations. Travel Behav. Soc. 2017, 6, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, K.B.; Scott, D.M. Insights into public transit use by Millennials: The Canadian experience. Travel Behav. Soc. 2018, 11, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, P.A.; Habib, K.N.; Morency, C. Mode use and trip length of seniors in Montreal. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 30, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, K.N. Modelling the choice and timing of acquiring a driver’s license: Revelations from a hazard model applied to the University students in Toronto. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, S.; Mitra, R. University Students’ Transportation Life-styles and the Role of Neighborhood Types and Attitudes (No. In 18-01770). In Proceedings of the 97th Annual Meeting of Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 7–11 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fatmi, M.R.; Habib, M.A. Modeling travel tool ownership of the elderly population: Latent segmentation-based logit model. Transp. Res. Rec. 2016, 2565, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatmi, M.R.; Habib, M.A.; Salloum, S.A. Modeling mobility tool ownership of youth in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2413, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenberg, E.; Brown, A.; Ralph, K.M.; Taylor, B.D.; Voulgaris, C.T. Typecasting Neighborhoods and Travelers: Analyzing the Geography of Travel Behavior among Teens and Young Adults in the US; US Department of Transportation (USDOT): Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Mattson, J.W. Travel Behavior and Mobility of Transportation-Disadvantaged Populations: Evidence from the National Household Travel Survey (No. DP-258); Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute: Fargo, ND, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Siren, A.; Haustein, S. Baby boomers’ mobility patterns and preferences: What are the implications for future transport? Transp. Policy 2013, 29, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haustein, S. Mobility behavior of the elderly: An attitude-based segmentation approach for a heterogeneous target group. Transportation 2011, 39, 1079–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böcker, L.; van Amen, P.; Helbich, M. Elderly travel frequencies and transport mode choices in Greater Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Transportation 2016, 44, 831–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boschmann, E.E.; Brady, S.A. Travel behaviors, sustainable mobility, and transit-oriented developments: A travel counts analysis of older adults in the Denver, Colorado metropolitan area. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, D.; Attard, M.; Ison, S. To drive or to use the bus? An exploratory study of older people in Malta. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 64, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Habib, K.N. An investigation on mode choice and travel distance demand of older people in the National Capital Region (NCR) of Canada: Application of a utility theoretic joint econometric model. Transportation 2015, 42, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Strawderman, L.; Adams-Price, C.; Turner, J.J. Transportation alternative preferences of the aging population. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, L.T.; Somenahalli, S.V.C. Exploring frequency of public transport use among older adults: A study in Adelaide, Australia. Travel Behav. Soc. 2015, 2, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthol, R. Transport resources, mobility and unmet transport needs in old age. Ageing Soc. 2012, 33, 1190–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardazzi, R.; Pazienza, M.G. Ageing and private transport fuel expenditure: Do generations matter? Energy Policy 2018, 117, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Siren, A. Seniors’ unmet mobility needs—How important is a driving licence? J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 41, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corran, P.; Steinbach, R.; Saunders, L.; Green, J. Age, disability and everyday mobility in London: An analysis of the correlates of ‘non-travel’ in travel diary data. J. Transp. Health 2018, 8, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, D.S.; Pereira, M.; Viana, C.M. Different destination, different commuting pattern? Analyzing the influence of the campus location on commuting. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuhnimhof, T.; Buehler, R.; Dargay, J. A new generation: Travel trends for young Germans and Britons. Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2230, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnimhof, T.; Armoogum, J.; Buehler, R.; Dargay, J.; Denstadli, J.M.; Yamamoto, T. Men shape a downward trend in car use among young Adults—Evidence from six industrialized countries. Transp. Rev. 2012, 32, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.; Dutzik, T.; Baxandall, P. Transportation and the New Generation: Why Young People Are Driving Less and What It Means for Transportation Policy; U.S. PIRG Education Fund & Frontier Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, T.J.; Wundersitz, L.N.; Raftery, S.J.; Baldock, M.R. Young Adult Licensing Trend and Travel Modes (No. 15/01); Royal Automobile Club of Victoria (RACV): Melbourne, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Circella, G.; Alemi, F.; Berliner, R.M.; Tiedeman, K.; Lee, Y.; Fulton, L.; Handy, S.; Mokhtarian, P.L. Multimodal behavior of millennials: Exploring differences in travel choices between young adults and gen-xers in California. In Proceedings of the 96th Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 8–12 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, K.N.; Weiss, A.; Hasnine, S. On the heterogeneity and substitution patterns in mobility tool ownership choices of post-secondary students: The case of Toronto. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2018, 116, 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnimhof, T.; Wirtz, M.; Manz, W. Decomposing young Germans’ altered car use patterns. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2320, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrington, A.; Mikolai, J. Young Adults’ Licence-Holding and Driving Behavior in the UK: Full Findings; The Royal Automobile Club Foundation for Motoring Ltd.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sivak, M.; Schoettle, B. Recent changes in the age composition of U.S. Drivers: Implications for the extent, safety, and environmental consequences of personal transportation. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2011, 12, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, D.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Clarys, P.; de Geus, B.; Vandelanotte, C.; van Cauwenberg, J.; Deforche, B. Choice of transport mode in emerging adulthood: Differences between secondary school students, studying young adults and working young adults and relations with gender, SES and living environment. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Blumenberg, E.; Taylor, B.; Ralph, K.; Voulgaris, C.T. A taste for transit? Analyzing public transit use trends among youth. J. Public Transp. 2016, 19, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alemi, F.; Circella, G.; Handy, S.; Mokhtarian, P. What influences travelers to use Uber? Exploring the factors affecting the adoption of on-demand ride services in California. Travel Behav. Soc. 2018, 13, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, T.; Hildebrand, E.D. Can rural older drivers meet their needs without a car? Stated adaptation responses from a GPS travel diary survey. Transportation 2011, 38, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmud, J.; Green, L.; Kuhnimhof, T.; le Vine, S.; Polak, J.; Phleps, P. Still going… and going: The emerging travel patterns of older adults. Institute for Mobility Research. 2017. Available online: https://www.ifmo.de/files/publications_content/2017/2017_ifmo_senior_generation_mobility_en.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Giesel, F.; Köhler, K. How poverty restricts elderly Germans’ everyday travel. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2015, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, V.; Johnson, R.M.; Rebok, G.W.; Roth, K.B.; Gielen, A.C.; Molnar, L.; Pitts, S.; DiGuiseppi, C.G.; Hill, L.L.; Strogatz, D.S.; et al. Use of alternative sources of transportation among older adult drivers. J. Transp. Health 2018, 10, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Michael, Y.; Zhang, H. Active travel, public transportation use, and daily transport among older adults: The association of built environment. J. Transp. Health 2018, 9, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthol, R.J.; Levin, L.; Siren, A. Mobility in different generations of older persons. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistner, D.L.; Steiner, R.L. Uber for seniors? Exploring transportation options for the future. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2660, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivoda, J.M.; Harmon, A.C.; Babulal, G.M.; Zikmund-Fisher, B.J. E-hail (rideshare) knowledge, use, reliance, and future expectations among older adults. Transp. Res. Part. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 55, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.J.; Adams-Price, C.E.; Strawderman, L. Formal alternative transportation options for older adults: An assessment of need. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2017, 60, 619–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siren, A.; Haustein, S. How do baby boomers’ mobility patterns change with retirement? Ageing Soc. 2015, 36, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthol, R. Decreasing popularity of the car? Changes in driving licence and access to a car among young adults over a 25-year period in Norway. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 51, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axhausen, K. Mobility Y: The Emerging Travel Patterns of Generation Y; Institute for Mobility Research: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muromachi, Y. Experiences of past school travel modes by university students and their intention of future car purchase. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2017, 104, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbosc, A.; Currie, G. Changing demographics and young adult driver license decline in Melbourne, Australia (1994–2009). Transportation 2013, 41, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Vine, S.; Polak, J. Factors associated with young adults delaying and forgoing driving licenses: Results from Britain. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2014, 15, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licaj, I.; Haddak, M.; Pochet, P.; Chiron, M. Individual and contextual socioeconomic disadvantages and car driving between 16 and 24 years of age: A multilevel study in the Rhone Departement (France). J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 22, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blumenberg, E.; Ralph, K.; Smart, M.J.; Taylor, B.D. Who knows about kids these days? Analyzing the determinants of youth and adult mobility in the U.S. between 1990 and 2009. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pr. 2016, 93, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoettle, B.; Sivak, M. The reasons for the recent decline in young driver licensing in the United States. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2013, 15, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnimhof, T.; Buehler, R.; Wirtz, M.; Kalinowska, D. Travel trends among young adults in Germany: Increasing multimodality and declining car use for men. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paepe, L.; van Acker, V.; Witlox, F.; de Vos, J. Changes in travel behavior during the transition from secondary to higher education: A case study from Ghent, Belgium. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hess, D.B. Walking to the bus: Perceived versus actual walking distance to bus stops for older adults. Transportation 2011, 39, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, M.J.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Siren, A. Comparing urban form correlations of the travel patterns of older and younger adults. Transp. Policy 2014, 35, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Cauwenberg, J.; Clarys, P.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I.; van Holle, V.; Verté, D.; de Witte, N.; de Donder, L.; Buffel, T.; Dury, S.; Deforche, B. Older adults’ transportation walking: A cross-sectional study on the cumulative influence of physical environmental factors. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2013, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnes, R.; Winters, M.; Ste-Marie, N.; McKay, H.; Ashe, M.C. Age and retirement status differences in associations between the built environment and active travel behavior. J. Transp. Health 2016, 3, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melia, S.; Chatterjee, K.; Stokes, G. Is the urbanisation of young adults reducing their driving? Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroesen, M.; Handy, S.L. Is the rise of the e-society responsible for the decline in car use by young adults? Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2496, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuokko, H.; Jouk, A.; Myers, A.; Marshall, S.; Man-Son-Hing, M.; Porter, M.M.; Bédard, M.; Gélinas, I.; Korner-Bitensky, N.; Mazer, B.; et al. A Re-examination of driving-related attitudes and readiness to change driving behavior in older adults. Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr. 2014, 32, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S.; Hunecke, M. Identifying target groups for environmentally sustainable transport: Assessment of different segmentation approaches. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jamal, S.; Newbold, K.B. Factors Associated with Travel Behavior of Millennials and Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198236

Jamal S, Newbold KB. Factors Associated with Travel Behavior of Millennials and Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198236

Chicago/Turabian StyleJamal, Shaila, and K. Bruce Newbold. 2020. "Factors Associated with Travel Behavior of Millennials and Older Adults: A Scoping Review" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8236. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198236