Improving Eating Habits at the Office: An Umbrella Review of Nutritional Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aim and Research Question

- What kind of nutrition interventions are used in the office setting?

- What workplace nutrition interventions are effective for office workers?

- What are the factors contributing to the effectiveness of workplace nutrition interventions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

- Population: office workers of all ages and genders;

- Interventions: dietary interventions, counselling, nutrition programs;

- Comparisons: not applicable;

- Outcomes: nutritional knowledge, economic indicators (e.g., absenteeism, presenteeism, costs) or health-related indicators (e.g., BMI, glucose levels, cholesterol levels, disease exacerbation, consumption of specific food groups);

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Type of study: meta-analysis or systematic reviews that covered quantitative, qualitative, or mixed method studies that were peer reviewed.

- Type of participants: office workers.

- Type of controls: not applicable.

- Type of outcomes: nutritional knowledge, economic or health-related indicators.

- Language: papers written in English.

- Studies that included grey literature or professional guidelines.

- Studies that focused on groups of workers other than the target population.

- Studies that aimed to analyze the relationship between physical activity participation/adherence and the effects of nutrition interventions.

- Studies published in languages other than English.

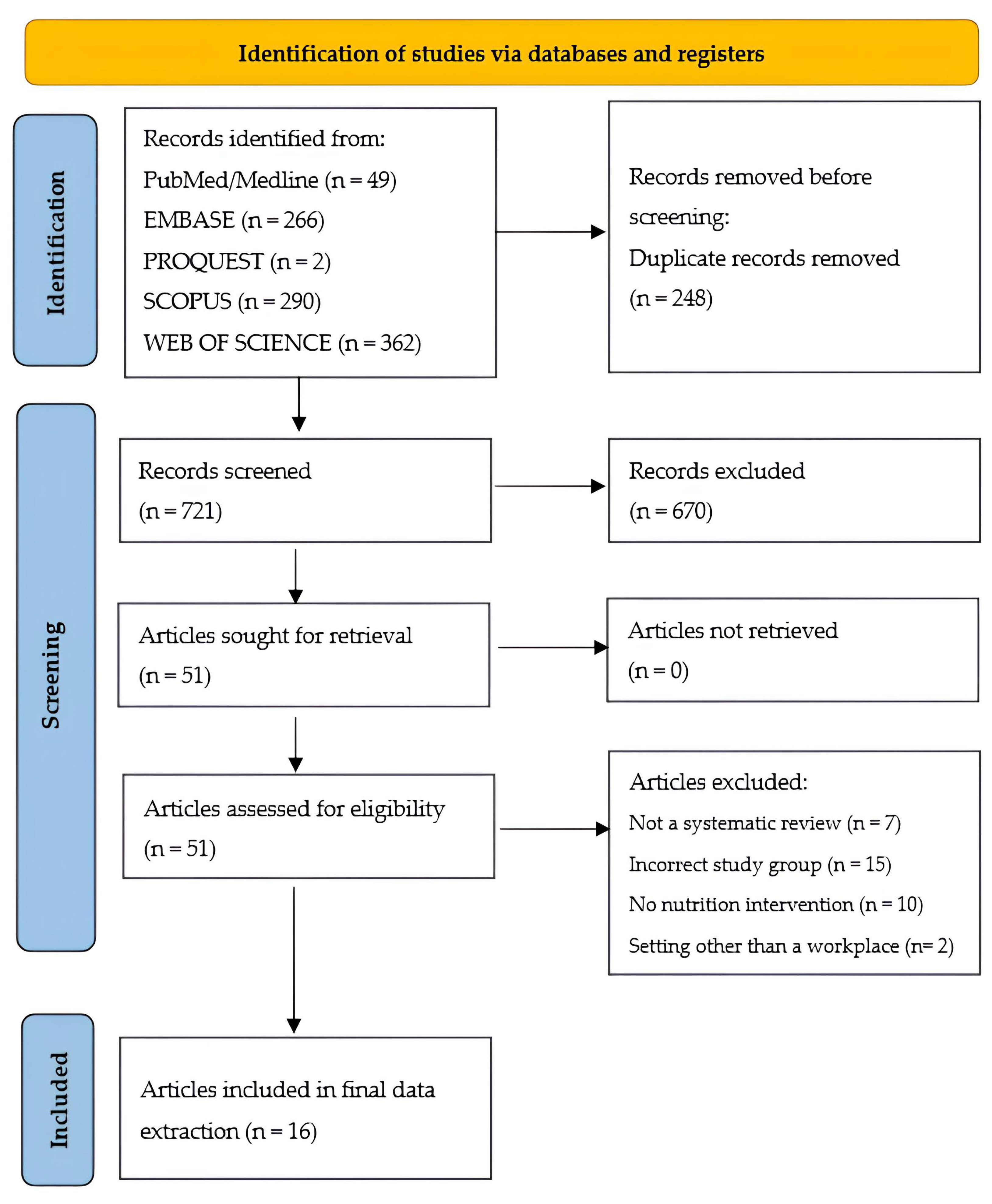

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Collection Process

2.5. Review Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Effect Measures

2.7. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Search Process

3.2. Description of Included Systematic Reviews

3.3. Reviews on Cognitive Interventions

3.4. Behavioural Intervention Reviews

3.5. Reviews on Mixed Interventions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Health Promotion Glossary of Terms; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muscaritoli, M. The Impact of Nutrients on Mental Health and Well-Being: Insights from the Literature. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 656290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/about-us/our-work/core-priorities/promoting-health-and-well-being (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Nielsen, K.N.M.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Känsälä, M.; Saari, E.; Isaksson, K. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 2017, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.M. The Value of Worker Well-Being. Public Health Rep. 2019, 134, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopman, C.; Pelletier, K.R.; Murray, J.F.; Sharda, C.E.; Berger, M.L.; Turpin, R.S.; Hackleman, P.; Gibson, P.; Holmes, D.M.; Bendel, T. Stanford presenteeism scale: Health status and employee productivity. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 44, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, T.; Rosenau, P.; Unruh, L.Y.; Barnes, A.J. United States: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2020, 22, 1–441. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, J. The history and impact of worksite wellness. Nurs. Econ. 1998, 16, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Top Employers Institute. HR Trends Report 2021—Priorities and Practices of the World’s Top Employers; Top Employers Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Grant Thornton. Medicover 2019. Zdrowy Pracownik, Zdrowy Pracodawca. Jak w Dobie Walki o Talenty Polscy Pracodawcy Dbają o Zdrowie Swoich Kadr; Grant Thornton: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniowska, E.; Puchalski, K. Co Firmy Powinny Wiedzieć, by Skutecznie Promować Zdrowe Odżywianie i Aktywność Fizyczną Pracowników? Raport z Wyników Reprezentatywnego Badania 1000 Pracowników Średnich i Dużych Firm w Polsce; Ministerstwo Zdrowia: Warsaw, Poland, 2019.

- World Health Organisation. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/activities/healthy-workplace (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- World Health Organisation. Healthy Workplaces: A Model for Action for Employers, Workers, Policy-Makers and Practitioners; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, K.; Korzeniowska, E.; Goszczyńska, E.; Petrykowska, A. Kto Wymaga Szczególnej Uwagi w Promocji Zdrowego Odżywiania i Aktywności Fizycznej w Firmach? Krajowe Centrum Promocji Zdrowia w Miejscu Pracy: Łódź, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, J.; Querstret, D.; Banas, K.; de Bruin, M. Environmental interventions for altering eating behaviours of employees in the workplace: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geaney, F.; Kelly, C.; Greiner, B.A.; Harrington, J.M.; Perry, I.J.; Beirne, P. The effectiveness of workplace dietary modification interventions: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Wada, K.; Shahrook, S.; Ota, E.; Takemi, Y.; Mori, R. Social marketing including financial incentive programs at worksite cafeterias for preventing obesity: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea Cabrera, A.; Caballero, P.; Wanden-Berghe, C.; Sanz-Lorente, M.; López-Pintor, E. Effectiveness of Workplace-Based Diet and Lifestyle Interventions on Risk Factors in Workers with Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendren, S.L.J. Impact of worksite cafeteria interventions on fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2017, 10, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, N.Y.; Lim, H.J.; Sung, S. Weight Reduction Interventions Using Digital Health for Employees with Obesity: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 3121–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmah, Q.; Martiana, T.; Mulyono, M.; Paskarini, I.; Dwiyanti, E.; Widajati, N.; Ernawati, M.; Ardyanto, Y.D.; Tualeka, A.R.; Haqi, D.N.; et al. The effectiveness of nutrition and health intervention in workplace setting: A systematic review. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 11, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papatheodorou, S.I.; Evangelou, E. Umbrella Reviews: What They Are and Why We Need Them. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2345, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frandsen, T.F.; Bruun Nielsen, M.F.; Lindhardt, C.L.; Eriksen, M.B. Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 127, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.V.; Valentine, J.C. (Eds.) The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L.M.; Quinn, T.A.; Glanz, K.; Ramirez, G.; Kahwati, L.C.; Johnson, D.B.; Buchanan, L.R.; Archer, W.R.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Kalra, G.P.; et al. The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; García, A.A.; Zuñiga, J.A.; Lewis, K.A. Effectiveness of workplace diabetes prevention programs: A systematic review of the evidence. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1036–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D.; Ali, M.U.; Horvath, S.; Nagpal, S.; Ghanem, S.; Sherifali, D. Effectiveness of Workplace Interventions to Reduce the Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Diabetes 2022, 46, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, K.; Eslami, A.; Pirzadeh, A.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Hosseini, F. Effects of the nutritional interventions in improving employee’s cardiometabolic risk factors in the workplace: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2022, 42, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, I.F.; Proper, K.I.; van der Beek, A.J.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; van Mechelen, W. Lifestyle-focused interventions at the workplace to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease--a systematic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2010, 36, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudzune, K.; Hutfless, S.; Maruthur, N.; Wilson, R.; Segal, J. Strategies to prevent weight gain in workplace and college settings: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, S.K.; Cordon, E.L.; Bailey, C.; Skouteris, H.; Ahuja, K.; Hills, A.P.; Hill, B. The effect of workplace lifestyle programmes on diet, physical activity, and weight-related outcomes for working women: A systematic review using the TIDieR checklist. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni Mhurchu, C.; Aston, L.M.; Jebb, S.A. Effects of worksite health promotion interventions on employee diets: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Effectiveness of worksite-based dietary interventions on employees’ obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2019, 13, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, V.; Andrade, J. Evaluation of Worksite Wellness Nutrition and Physical Activity Programs and Their Subsequent Impact on Participants’ Body Composition. J. Obes. 2018, 2018, 1035871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Dusenbury, L. Worksite cholesterol and nutrition: An intervention project in Colorado. Aaohn. J. 1999, 47, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ard, J.D.; Cox, T.L.; Zunker, C.; Wingo, B.C.; Jefferson, W.K.; Brakhage, C. A study of a culturally enhanced EatRight dietary intervention in a predominately African American workplace. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2010, 16, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, T.; Mullis, R.; Anderson, J.; Dusenbury, L.; Gorsky, R.; Kimber, C.; Krueger, K.; Kuester, S.; Mokdad, A.; Perry, G. The costs and effects of a nutritional education program following work-site cholesterol screening. Am. J. Public Health 1995, 85, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edye, B.V.; Mandryk, J.A.; Frommer, M.S.; Healey, S.; Ferguson, D.A. Evaluation of a worksite programme for the modification of cardiovascular risk factors. Med. J. Aust. 1989, 150, 574, 576–578, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J.T. Improved plasma cholesterol levels in men after a nutrition education program at the worksite. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 1993, 93, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briley, M.E.; Montgomery, D.H.; Blewett, J. Worksite nutrition education can lower total cholesterol levels and promote weight loss among police department employees. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 1992, 92, 1382–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily Fruits. Raport—Wpływ Pracy Zdalnej na Nawyki Żywieniowe Polaków; Daily Fruits: Marlboro, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Contento, I.R. Nutrition education: Linking research, theory, and practice. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17 (Suppl. S1), 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- ICAN Institute. Raport “Benefity Przyszłości”; ICAN Institute: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Goudie, S. The Broken Plate 2023. The state of the Nation’s Food System; The Food Foundation: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Milne-Ives, M.; Lam, C.; De Cock, C.; Van Velthoven, M.H.; Meinert, E. Mobile Apps for Health Behavior Change in Physical Activity, Diet, Drug and Alcohol Use, and Mental Health: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, K.; Bohnet-Joschko, S. Selling health and happiness how influencers communicate on Instagram about dieting and exercise: Mixed methods research. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Wilkinson, S.; Downie, O.; Truby, H. Communication of nutrition information by influencers on social media: A scoping review. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2022, 33, 657–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contento, I.R. Edukacja Żywieniowa, 1st ed.; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; ISBN 978-83-01-19857-2. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Year) | Number of Primary Surveys | Number of Participants | Type of Primary Research | Type of Intervention | Type of Review | Quality Assessment of Primary Research (Yes/No; Name of Tool) | AMSTAR2 Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allan et al. (2017) [15] | 22 | N/A * | RCTs, Quasi-experiments | Behavioural | Systematic review | Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool | Low |

| Anderson et al. (2009) [29] | 47 | 76,941 ** | RCTs, Quasi-experiments, Observational studies | Mixed | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Community Guide | Moderate |

| Brown et al. (2018) [30] | 22 | 35,197 | RCTs, Quasi-experiments, Observational studies | Behavioural | Systematic review | Cochrane criteria | Low |

| Cabrera et al. (2021) [18] | 13 | 5423 | RCTs, Quasi-experiments | Mixed | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Not specified | Low |

| Fitzpatrick-Lewis et al. (2022) [31] | 5 | 1494 | RCTs, Observational studies | Mixed | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Cochrane Risk of Bias 1 tool | Low |

| Geaney et al. (2013) [16] | 6 | N/A * | RCTs, Quasi-experiments | Behavioural | Systematic review | Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool | Low |

| Ghobadi et al. (2022) [32] | 8 | 1797 | RCTs | Mixed | Systematic review | Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool | Low |

| Groeneveld et al. (2010) [33] | 31 | 16,013 | RCTs, Quasi-experiments | Mixed | Systematic review | Delhi list based tool | Low |

| Gudzune et al. (2013) [34] | 9 | 76,465 ** | RCTs, Quasi-experiments | Mixed | Systematic review | Downs and Black methodological quality assessment checklist | Low |

| Hendren et al. (2017) [19] | 18 | 37,744 | RCTs | Mixed | Systematic review | Quality characteristics and bias criteria were adapted from two previously published systematic reviews | Low |

| Lee et al. (2022) [20] | 11 | 13,233 | RCTs | Mixed | Systematic review | The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomised Controlled Trials | Low |

| Madden et al. (2020) [35] | 20 | 3311 | RCTs, Quasi-experiments | Mixed | Systematic review | Cochrane Risk of Bias, ROBINS-I (risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions) | Low |

| Ni Mhurchu et al. (2010) [36] | 16 | N/A * | RCTs, Quasi-experiments | Mixed | Systematic review | A checklist adapted from a previous review | Low |

| Park et al. (2019) [37] | 7 | 2854 | RCTs | Behavioural | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Cochrane’s Risk of Bias | Low |

| Sandercock et al. (2018) [38] | 23 | 41,867 | RCTs, Quasi-experiments, Observational studies | Mixed | Systematic review | Quality Criteria Checklist from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) Evidence Analysis Manual | Low |

| Sawada et al. (2019) [17] | 3 | 3013 | RCTs | Behavioural | Systematic review | GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) | Low |

| Author (Year) | Description of the Intervention | Results | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allan et al. (2016) [15] | Environmental intervention (environmental intervention) affecting eating habits | For behavioural endpoints, 13 of 22 studies showed a significant effect on primary endpoints. For physical endpoints, some studies showed no difference in BMI or body weight, while others confirmed it. | The current state of knowledge does not allow for clear recommendations for introducing environmental interventions to change eating habits in the workplace. |

| Brown et al. (2017) [30] | Workplace well-being programs to prevent or treat diabetes (nutrition—cooking workshops, individual dietary consultations, dietary changes; physical activity pedometers, workout plans; smoking cessation; usually in combination) | The study demonstrated a steady improvement in health in biological measures, self-reported behavioural adherence measures, and psychosocial variables. The authors presented data that showed improvement in most cases. | Workplace diabetes prevention programs can be useful in reducing disease occurrence and progression, but better design of interventions is needed. Employer education and further research in this area are crucial. |

| Geaney et al. (2013) [16] | Change in the composition of meals available at work, change in portion sizes (usually reduction), changes in access to healthy products for employees. | All of the included studies showed changes in fruits and vegetables intake, but none showed an effect size greater than a half-portion increase in fruit and vegetables consumption. | Modification of workers’ meals may increase fruit and vegetables intake, but the strength of evidence is low. |

| Park et al. (2019) [37] | A nutritional intervention that limits the intake of energy and certain nutrients (carbohydrates or fats) or a balanced diet that ensures a normal supply of all nutrients | Employees’ body weight decreased significantly: WMD of −4.37 kg (95% CI −6.54 to −2.20; Z = 3.95, p < 0.001), so did BMI: WMD of −1.26 (95% CI −1.98 to −0.55) kg/m2, but it was statistically significant (Z = 3.47, p = 0.001), blood cholesterol and blood pressure values also declined—but the problem is the duration of the study and the quality of the data. | It is challenging to definitely state the effectiveness of interventions, but it is a good start for further research. |

| Sawada et al. (2019) [17] | Discounts on healthy food products or for a smaller portion ordered in the employee cafeteria, colour-coding of dishes (yellow, green and red), | No significant changes in BMI, blood cholesterol levels or changes in diet | Link between the intervention and the outcomes cannot be established; poor quality of evidence; a need for further research in this area. |

| Author (Year) | Description of the Intervention | Results | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (2009) [29] | Environmental, educational or behavioural interventions to achieve and/or maintain a healthy body weight | There is evidence of a modest reduction in body weight as a result of workplace health promotion programs aimed at improving nutrition, physical activity or both. Program effects are consistent, with a net loss of 2.8 pounds (95% CI −4.63, −0.96) among workers at 6–12-month follow-up, based on the meta-analysis of nine RCTs. In terms of BMI, a net loss of 0.47 BMI (95% CI −1.02, −0.2) at 6–12 months was observed in six RCTs. | There is strong evidence of a consistent, although small, effect (weight loss), in both men and women. The research quality is lacking and indicates the need and room for more research. |

| Cabrera et al. (2021) [18] | Basic nutrition education and general nutrition counselling, implementation of a specific diet, or dietary changes, motivational changes and/or coaching, physical activity and stress and/or sleep quality management. Most of the interventions studied were partially or fully delivered online using online platforms and/or social media | The effects of nutritional interventions: reduction in waist circumference (−4.9 cm, 95% CI −8.0 to −1.7), systolic blood pressure (−6.5 mmHg, 95% CI −10.7 to −2.3), diastolic blood pressure (−1.9 mmHg, 95% CI −3.6 to −0.2), triglycerides (SMD −0.46, 95% CI −0.88 to −0.04) fasting glucose (SMD −0.68, 95% CI −1.20 to −0.15). | Nutrition interventions in the workplace are beneficial for employees with the metabolic syndrome in terms of preventing the disease and also improving health parameters. Interventions that affect health-related behaviours and attitudes, as well as employee motivation, are the most effective—purely educational interventions are the most common but do not yield the anticipated outcomes. |

| Fitzpatrick-Lewis et al. (2022) [31] | A diabetes prevention program or a program with 3 components of diabetes prevention (nutrition educator/coach, focus on nutrition and increased physical activity) | Participants in diabetes prevention programs were 3.85 times more likely to lose weight ≥ 5% (4 RCTs; RR = 3.85; 95% CI, 1.58 to 9.38; p < 0.05) and had a 9.36-fold greater chance of weight loss ≥ 7% (2 RCTs; RR = 9.36; 95% CI, 2.31 to 37.97; p < 0.05), a significant reduction in BMI was observed (5 RCTs; MD = −0.86; 95% CI, −1.37 to −0.34; p < 0.05). Interventions based on diabetes prevention programs were 2.12 times more effective in increasing physical activity compared to the control group (RR = 2.12; 95% CI, 1.06 to 4.25; p < 0.05). | The quality of these data are low to average. Due to doubts about the quality of the data and its limited availability, further research is needed in this area. |

| Ghobadi et al. (2022) [32] | Nutrition interventions: educational, counseling and environmental | Improvements in lipid indices (HDL, LDL) were observed. Available data say that while dietary interventions are effective in improving the cholesterol profile, they do not affect other variables. | More high-quality primary research is needed to confirm these relationships. |

| Gudzune et al. (2013) [34] | Self-management, dietary, physical activity and/or environmental intervention | There were no statistically significant changes in body weight and BMI in either women or men. However, those in the group with a higher BMI at baseline who received the intervention lost weight, while those in the control group gained weight (a statistically significant relationship). | There is weak to moderate evidence that self-management, dietary, physical activity and/or environmental interventions prevent weight gain in workers. |

| Groeneveld et al. (2010) [33] | Lifestyle or health promotion intervention with emphasis on nutrition and physical activity | There is no evidence that interventions of this type have a positive effect on body weight, blood pressure values, lipid profile or glucose levels. In contrast, there is strong evidence of their effect on fat reduction. | The effectiveness of interventions depends on whether the patients included in the study were at CVD risk or not, with interventions working better for those at risk. |

| Hendren et al. (2017) [19] | Greater availability of fruit and vegetables, subsidies for healthy produce, changing menus/portion sizes, education at point of purchase, combination of education and community intervention | It showed an increase in fruit and vegetables intake which was statistically significant in 13 out of 14 studies (p < 0.05). Only one study showed a statistically significant decrease (p = 0.007). Three studies produced mixed results. One study showed a significant increase in vegetable intake (p = 0.002) but no change in fruit intake (p = 0.78). Another study showed a significant increase in fruit consumption (p = 0.001) but no change in salad sales (p = 0.139). | Environmental interventions conducted at the employee cafeteria/canteen can increase fruit and vegetable consumption, but the lack of consistency in the available literature limits the development of specific recommendations. |

| Lee et al. (2022) [20] | Weight loss interventions carried out using electronic devices such as computers, tablets, smartphones, apps and personal electronic assistants | Video consultations appear to be more effective than face-to-face appointments, while wearable devices (telemedicine devices, smartwatches and smart phones) and apps have proven to be the most effective. | As technology advances, the form of the message has to be updated. Also, these interventions lack a theoretical foundation—indicating the potential for future research. |

| Madden et al. (2020) [35] | Lifestyle programs to improve diet, physical activity and weight-related factors | In mixed activities (diet + physical activity), interventions that were not led by a health worker (possibly a healthcare worker and someone who is not—at the same time) were more effective. Emphasis was placed on how the interventions were delivered and on responding to the needs of female employees. | Proper social support and the right choice of interventions are key to the effectiveness of interventions with female employees. |

| Ni Mhurchu et al. (2010) [36] | A weight loss or healthy eating intervention in the workplace, lasting a minimum of 8 weeks | None of the studies showed measurable effects on presenteeism, productivity and/or health care costs. Overall, the effects of dietary interventions were positive, but the self-reported nature of dietary assessment poses a high risk of error. | Nutrition interventions in the workplace have a positive, though small, effect on employees’ eating habits. |

| Sandercock et al. (2018) [38] | Physical activity and nutrition education | The results of some studies have shown statistically significant changes in body composition (lower BMI, body fat percentage and waist circumference). Even though changes in body composition have been confirmed in other studies, the results are not statistically significant. Six interventions showed no change, and one showed an increase in BMI. | Interventions affect the body composition of the study participants, but the strength of evidence is low. More studies with better endpoint determination are needed—the authors suggest, e.g., BIA. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hyży, A.; Jaworski, M.; Cieślak, I.; Gotlib-Małkowska, J.; Panczyk, M. Improving Eating Habits at the Office: An Umbrella Review of Nutritional Interventions. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245072

Hyży A, Jaworski M, Cieślak I, Gotlib-Małkowska J, Panczyk M. Improving Eating Habits at the Office: An Umbrella Review of Nutritional Interventions. Nutrients. 2023; 15(24):5072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245072

Chicago/Turabian StyleHyży, Aleksandra, Mariusz Jaworski, Ilona Cieślak, Joanna Gotlib-Małkowska, and Mariusz Panczyk. 2023. "Improving Eating Habits at the Office: An Umbrella Review of Nutritional Interventions" Nutrients 15, no. 24: 5072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245072

APA StyleHyży, A., Jaworski, M., Cieślak, I., Gotlib-Małkowska, J., & Panczyk, M. (2023). Improving Eating Habits at the Office: An Umbrella Review of Nutritional Interventions. Nutrients, 15(24), 5072. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15245072