Resveratrol and Amyloid-Beta: Mechanistic Insights

Abstract

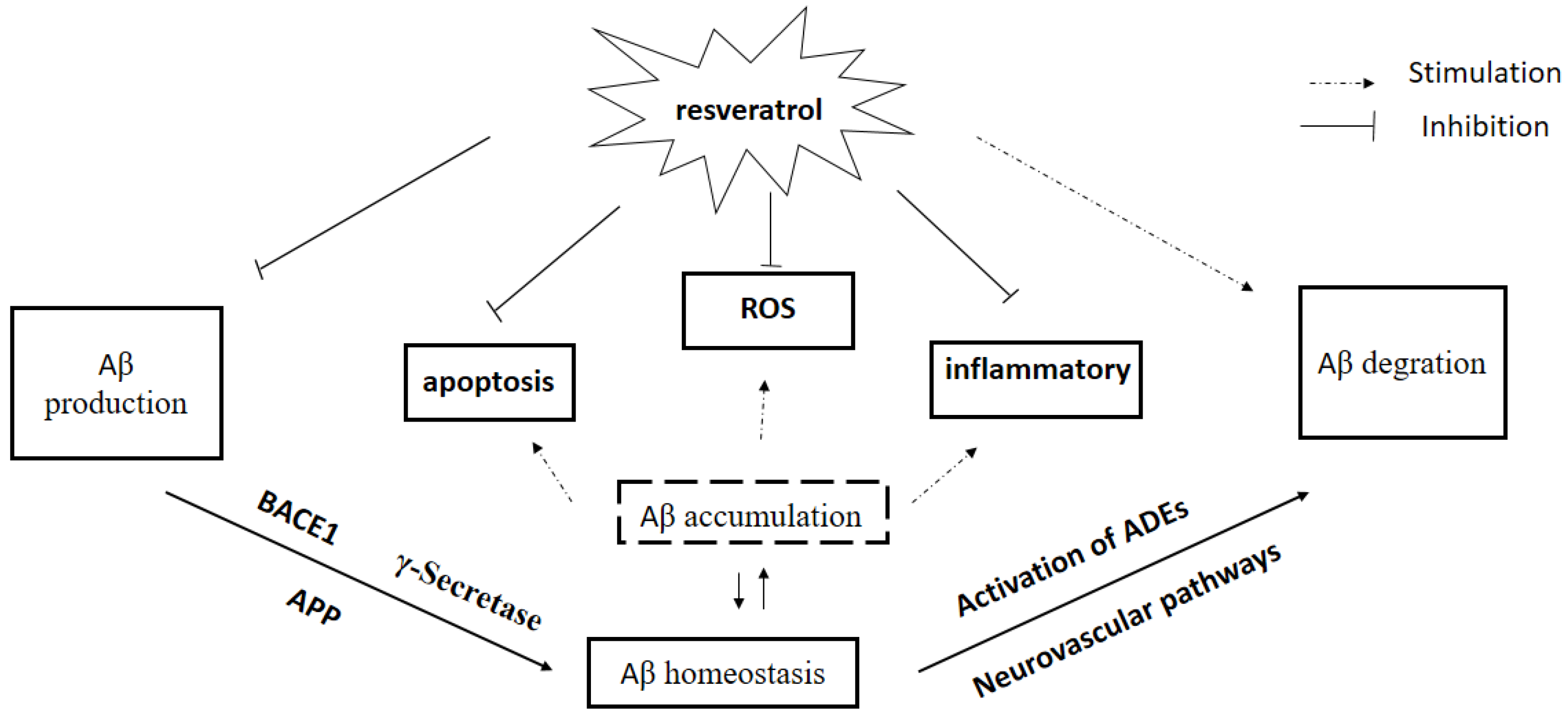

:1. Introduction

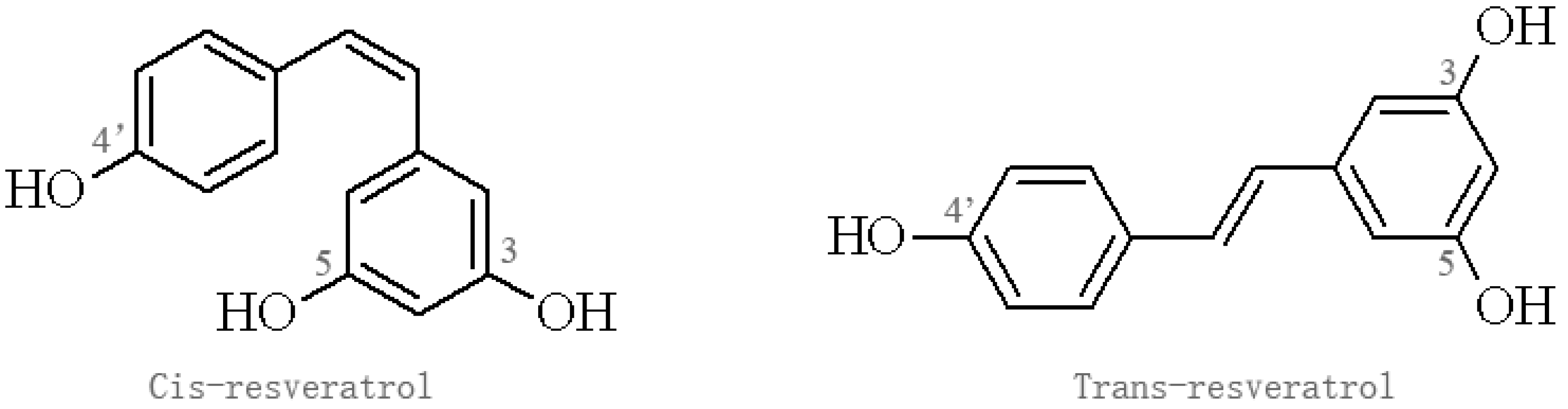

2. The Source and Pharmacological Profile of Res

3. Effect of Res on Aβ Production

3.1. Inhibitory Activity against BACE1

3.2. Inhibitory Activity against γ-Secretase

3.3. Autophagy Induction

4. Effect of Res on Aβ Clearance

4.1. Activation of ADEs

4.2. Plasminogen System

4.3. Neurovascular Pathways

4.3.1. BBB Integrity

4.3.2. P-gp

4.3.3. LRP1

4.3.4. RAGE

5. Aβ Plaque Disruption

6. Res Analogs in AD Treatment

7. Conclusions and Challenges

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Wijngaarden, P.; Hadoux, X.; Alwan, M.; Keel, S.; Dirani, M. Emerging ocular biomarkers of Alzheimer disease. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2017, 45, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarawneh, R.; Holtzman, D.M. The clinical problem of symptomatic Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, A.; Nelson, A.R.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. Impaired vascular-mediated clearance of brain amyloid β in Alzheimer’s disease: The role, regulation and restoration of LRP1. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, R.J.; Wong, P.C. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ries, M.; Sastre, M. Mechanisms of aβ clearance and degradation by glial cells. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, M.; Tachibana, M.; Kanekiyo, T.; Bu, G. Role of LRP1 in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence from clinical and preclinical studies. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, N.K.; Jha, S.K.; Kumar, D.; Kejriwal, N.; Sharma, R.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. Impact of insulin degrading enzyme and neprilysin in Alzheimer’s disease biology: Characterization of putative cognates for therapeutic applications. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 48, 891–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Assema, D.M.; van Berckel, B.N. Blood-brain barrier ABC-transporter P-glycoprotein in Alzheimer’s disease: Still a suspect? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 5808–5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huo, X.; Wang, C.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Q.; Sun, H.; Sun, P.; Yang, X.; Shu, X.; et al. Enhancement effect of resveratrol on the intestinal absorption of bestatin by regulating PEPT1, MDR1 and MRP2 in vivo and in vitro. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 495, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rege, S.D.; Geetha, T.; Griffin, G.D.; Broderick, T.L.; Babu, J.R. Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol in Alzheimer disease pathology. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braidy, N.; Jugder, B.E.; Poljak, A.; Jayasena, T.; Mansour, H.; Nabavi, S.M.; Sachdev, P.; Grant, R. Resveratrol as a potential therapeutic candidate for the treatment and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.H.; Surh, Y.J. Protective effect of resveratrol on β-amyloid-induced oxidative PC12 cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liang, N.; Zhu, D.; Gao, Q.; Peng, L.; Dong, H.; Yue, Q.; Liu, H.; Bao, L.; Zhang, J.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits β-amyloid-induced neuronal apoptosis through regulation of SIRT1-ROCK1 signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capiralla, H.; Vingtdeux, V.; Zhao, H.; Sankowski, R.; Al-Abed, Y.; Davies, P.; Marambaud, P. Resveratrol mitigates lipopolysaccharide- and Aβ-mediated microglial inflammation by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-KAPPAB/STAT signaling cascade. J. Neurochem. 2012, 120, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garwood, C.J.; Pooler, A.M.; Atherton, J.; Hanger, D.P.; Noble, W. Astrocytes are important mediators of Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and tau phosphorylation in primary culture. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollvander, S.; Nikitidou, E.; Brolin, R.; Soderberg, L.; Sehlin, D.; Lannfelt, L.; Erlandsson, A. Accumulation of amyloid-β by astrocytes result in enlarged endosomes and microvesicle-induced apoptosis of neurons. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, F.U.; Shah, S.A.; Kim, M.O. Vanillic acid attenuates Aβ1-42-induced oxidative stress and cognitive impairment in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; He, M.; Cao, J.; Wang, H.; Ding, J.; Jiao, Y.; Li, R.; He, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y. The comparative analysis of the potential relationship between resveratrol and stilbene synthase gene family in the development stages of grapes (vitis quinquangularis and vitis vinifera). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 74, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikumar, K.B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Resveratrol: A multitargeted agent for age-associated chronic diseases. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 1020–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.M.; Ha, Y.M.; Kim, J.A.; Chung, K.W.; Uehara, Y.; Lee, K.J.; Chun, P.; Byun, Y.; Chung, H.Y.; Moon, H.R. Synthesis of novel azo-resveratrol, azo-oxyresveratrol and their derivatives as potent tyrosinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 7451–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boocock, D.J.; Faust, G.E.; Patel, K.R.; Schinas, A.M.; Brown, V.A.; Ducharme, M.P.; Booth, T.D.; Crowell, J.A.; Perloff, M.; Gescher, A.J.; et al. Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, M.A.; Morris, B.J. Resveratrol in prevention and treatment of common clinical conditions of aging. Clin. Interv. Aging 2008, 3, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.D.; Burdock, G.A.; Edwards, J.A.; Beck, M.; Bausch, J. Safety studies conducted on high-purity trans-resveratrol in experimental animals. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkon, A.; Somoza, V. Quantification of free and protein-bound trans-resveratrol metabolites and identification of trans-resveratrol-c/o-conjugated diglucuronides—Two novel resveratrol metabolites in human plasma. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, G.; Dileo, J.N.; Hallas, B.H.; Horowitz, J.M.; Leheste, J.R. Silent information regulator 1 mediates hippocampal plasticity through presenilin1. Neuroscience 2011, 179, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, N.S.; Bayan, Y. Possible role of resveratrol targeting estradiol and neprilysin pathways in lipopolysaccharide model of Alzheimer disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 822, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.M.; Rodrigues, D.; Alemi, M.; Silva, S.C.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Cardoso, I. Resveratrol administration increases transthyretin protein levels ameliorating AD features—Importance of transthyretin tetrameric stability. Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.F.; Li, N.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, X.J.; Li, X.M.; Liu, T.T. Resveratrol decreases the insoluble Aβ1–42 level in hippocampus and protects the integrity of the blood-brain barrier in ad rats. Neuroscience 2015, 310, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.W.; Choi, Y.H.; Cha, M.R.; Kim, Y.S.; Yon, G.H.; Hong, K.S.; Park, W.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Ryu, S.Y. In vitro BACE-1 inhibitory activity of resveratrol oligomers from the seed extract of paeonia lactiflora. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koukoulitsa, C.; Villalonga-Barber, C.; Csonka, R.; Alexi, X.; Leonis, G.; Dellis, D.; Hamelink, E.; Belda, O.; Steele, B.R.; Micha-Screttas, M.; et al. Biological and computational evaluation of resveratrol inhibitors against Alzheimer’s disease. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016, 31, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.; Kim, S.; Jang, B.-G.; Kim, M.-J. Piceatannol, a natural analogue of resveratrol, effectively reduces β-amyloid levels via activation of alpha-secretase and matrix metalloproteinase-9. J. Funct. Foods 2009, 23, 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, K.; Mizuno, A.; Ueda, M.; Li, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Hida, Y.; Hayakawa-Yano, Y.; Itoh, M.; Ohta, E.; Kobori, M.; et al. Autophagy impairment stimulates PS1 expression and gamma-secretase activity. Autophagy 2010, 6, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzig, M.F.; Escher, F. Induction of neutral endopeptidase and angiotensin-converting enzyme activity of SK-N-SH cells in vitro by quercetin and resveratrol. Pharmazie 2002, 57, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.F.; Qiao, J.P.; Qi, C.C.; Wang, C.W.; Zhou, J.N. The binding of resveratrol to monomer and fibril amyloid β. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 61, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willem, M.; Garratt, A.N.; Novak, B.; Citron, M.; Kaufmann, S.; Rittger, A.; DeStrooper, B.; Saftig, P.; Birchmeier, C.; Haass, C. Control of peripheral nerve myelination by the β-secretase BACE1. Science 2006, 314, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagno, E.; Bardini, P.; Guglielmotto, M.; Danni, O.; Tabaton, M. The various aggregation states of β-amyloid 1–42 mediate different effects on oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, and BACE-1 expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skretas, G.; Meligova, A.K.; Villalonga-Barber, C.; Mitsiou, D.J.; Alexis, M.N.; Micha-Screttas, M.; Steele, B.R.; Screttas, C.G.; Wood, D.W. Engineered chimeric enzymes as tools for drug discovery: Generating reliable bacterial screens for the detection, discovery, and assessment of estrogen receptor modulators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 8443–8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marambaud, P.; Zhao, H.; Davies, P. Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-β peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 37377–37382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, K.; Koo, E.H. Emerging therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Strooper, B. APH-1, PEN-2, and nicastrin with presenilin generate an active gamma-secretase complex. Neuron 2003, 38, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acx, H.; Serneels, L.; Radaelli, E.; Muyldermans, S.; Vincke, C.; Pepermans, E.; Muller, U.; Chavez-Gutierrez, L.; De Strooper, B. Inactivation of gamma-secretases leads to accumulation of substrates and non-Alzheimer neurodegeneration. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, V.; Song, X.; Wiesner, A.; Ittner, L.M.; Baysang, G.; Meier, F.; Ozmen, L.; Bluethmann, H.; Drose, S.; Brandt, U.; et al. Amyloid-β and tau synergistically impair the oxidative phosphorylation system in triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20057–20062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kesidou, E.; Lagoudaki, R.; Touloumi, O.; Poulatsidou, K.N.; Simeonidou, C. Autophagy and neurodegenerative disorders. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 2275–2283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rubinsztein, D.C.; Marino, G.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy and aging. Cell 2011, 146, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, M.; Rockenstein, E.; Crews, L.; Masliah, E. Role of protein aggregation in mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Neuromol. Med. 2003, 4, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, K.; Eckman, C.; Zehr, C.; Yu, X.; Prada, C.M.; Perez-tur, J.; Hutton, M.; Buee, L.; Harigaya, Y.; Yager, D.; et al. Increased amyloid-β 42 (43) in brains of mice expressing mutant presenilin 1. Nature 1996, 383, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, R.A.; Yang, D.S. Autophagy failure in Alzheimer’s disease—Locating the primary defect. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 43, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, T.; Javed, S.; Javed, S.; Tariq, A.; Samec, D.; Tejada, S.; Nabavi, S.F.; Braidy, N.; Nabavi, S.M. Resveratrol and Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanistic insights. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 2622–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Mi, M.T. Resveratrol attenuates Aβ25–35 caused neurotoxicity by inducing autophagy through the TYrRS-PARP1-SIRT1 signaling pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 2367–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalivaeva, N.N.; Beckett, C.; Belyaev, N.D.; Turner, A.J. Are amyloid-degrading enzymes viable therapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease? J. Neurochem. 2012, 120 (Suppl. 1), 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.S.; Jo, S.A. Mechanisms of amyloid-β peptide clearance: Potential therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease. Biomol. Ther. 2012, 20, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Xiong, H.; Callaghan, D.; Liu, H.; Jones, A.; Pei, K.; Fatehi, D.; Brunette, E.; Stanimirovic, D. Blood-brain barrier transport of amyloid β peptides in efflux pump knock-out animals evaluated by in vivo optical imaging. Fluids Barriers CNS 2013, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghobeh, M.; Ahmadian, S.; Meratan, A.A.; Ebrahim-Habibi, A.; Ghasemi, A.; Shafizadeh, M.; Nemat-Gorgani, M. Interaction of Aβ (25–35) fibrillation products with mitochondria: Effect of small-molecule natural products. Biopolymers 2014, 102, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miners, J.S.; Barua, N.; Kehoe, P.G.; Gill, S.; Love, S. Aβ-degrading enzymes: Potential for treatment of Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 70, 944–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Quinto, J.; Herdt, A.; Eckman, C.B.; Eckman, E.A. Endothelin-converting enzymes and related metalloproteases in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013, 33 (Suppl. 1), 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Coppa, T.; Lazze, M.C.; Cazzalini, O.; Perucca, P.; Pizzala, R.; Bianchi, L.; Stivala, L.A.; Forti, L.; Maccario, C.; Vannini, V.; et al. Structure-activity relationship of resveratrol and its analogue, 4,4’-dihydroxy-trans-stilbene, toward the endothelin axis in human endothelial cells. J. Med. Food 2011, 14, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyganowska-Swiatkowska, M.; Surdacka, A.; Skrzypczak-Jankun, E.; Jankun, J. The plasminogen activation system in periodontal tissue. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 33, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.L.; Zhan, D.M.; Xi, S.H.; He, X.L. Roles of tissue plasminogen activator and its inhibitor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 7, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rakic, J.M.; Maillard, C.; Jost, M.; Bajou, K.; Masson, V.; Devy, L.; Lambert, V.; Foidart, J.M.; Noel, A. Role of plasminogen activator-plasmin system in tumor angiogenesis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2003, 60, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salles, F.J.; Strickland, S. Localization and regulation of the tissue plasminogen activator-plasmin system in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 2125–2134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Melchor, J.P.; Pawlak, R.; Strickland, S. The tissue plasminogen activator-plasminogen proteolytic cascade accelerates amyloid-β (Aβ) degradation and inhibits Aβ-induced neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 8867–8871. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ertekin-Taner, N.; Ronald, J.; Feuk, L.; Prince, J.; Tucker, M.; Younkin, L.; Hella, M.; Jain, S.; Hackett, A.; Scanlin, L.; et al. Elevated amyloid β protein (Aβ42) and late onset Alzheimer’s disease are associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms in the urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchigna, S.; Lambrechts, D.; Carmeliet, P. Neurovascular signalling defects in neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, F.C.; Liu, R.; Lu, P.; Shapiro, A.B.; Renoir, J.M.; Sharom, F.J.; Reiner, P.B. β-Amyloid efflux mediated by p-glycoprotein. J. Neurochem. 2001, 76, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candela, P.; Gosselet, F.; Saint-Pol, J.; Sevin, E.; Boucau, M.C.; Boulanger, E.; Cecchelli, R.; Fenart, L. Apical-to-basolateral transport of Amyloid-β peptides through blood-brain barrier cells is mediated by the receptor for advanced glycation end-products and is restricted by p-glycoprotein. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 22, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.D.; Bierhaus, A.; Nawroth, P.P.; Stern, D.M. RAGE and Alzheimer’s disease: A progression factor for amyloid-β-induced cellular perturbation? J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009, 16, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagare, A.; Deane, R.; Bell, R.D.; Johnson, B.; Hamm, K.; Pendu, R.; Marky, A.; Lenting, P.J.; Wu, Z.; Zarcone, T.; et al. Clearance of amyloid-β by circulating lipoprotein receptors. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deane, R.; Wu, Z.; Sagare, A.; Davis, J.; Du Yan, S.; Hamm, K.; Xu, F.; Parisi, M.; LaRue, B.; Hu, H.W.; et al. LRP/amyloid β-peptide interaction mediates differential brain efflux of Aβ isoforms. Neuron 2004, 43, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, A.; Sarkar, C.; Singh, S.P.; Zhang, Z.; Munasinghe, J.; Peng, S.; Chandra, G.; Kong, E.; Mukherjee, A.B. The blood-brain barrier is disrupted in a mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: Amelioration by resveratrol. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2233–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgetown University Medical Center. Resveratrol Appears to Restore Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/07/160727140041.htm (accessed on 27 July 2016).

- Moussa, C.; Hebron, M.; Huang, X.; Ahn, J.; Rissman, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Turner, R.S. Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordon-Cardo, C.; O′Brien, J.P.; Casals, D.; Rittman-Grauer, L.; Biedler, J.L.; Melamed, M.R.; Bertino, J.R. Multidrug-resistance gene (P-glycoprotein) is expressed by endothelial cells at blood-brain barrier sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, A.K.; Borson, S.; Link, J.M.; Domino, K.; Eary, J.F.; Ke, B.; Richards, T.L.; Mankoff, D.A.; Minoshima, S.; O’Sullivan, F.; et al. Activity of P-glycoprotein, a β-amyloid transporter at the blood-brain barrier, is compromised in patients with mild Alzheimer disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R.S.; Thomas, R.G.; Craft, S.; van Dyck, C.H.; Mintzer, J.; Reynolds, B.A.; Brewer, J.B.; Rissman, R.A.; Raman, R.; Aisen, P.S.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2015, 85, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieckmann, M.; Dietrich, M.F.; Herz, J. Lipoprotein receptors—An evolutionarily ancient multifunctional receptor family. Biol. Chem. 2010, 391, 1341–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagare, A.P.; Deane, R.; Zlokovic, B.V. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1: A physiological Aβ homeostatic mechanism with multiple therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 136, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, R.D.; Deane, R.; Chow, N.; Long, X.; Sagare, A.; Singh, I.; Streb, J.W.; Guo, H.; Rubio, A.; Van Nostrand, W.; et al. SRF and myocardin regulate LRP-mediated amyloid-β clearance in brain vascular cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoforidis, M.; Schober, R.; Krohn, K. Genetic-morphologic association study: Association between the low density lipoprotein-receptor related protein (LRP) and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2005, 31, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, G.D.; Messier, A.A.; Miller, M.C.; Machan, J.T.; Majmudar, S.S.; Stopa, E.G.; Donahue, J.E.; Johanson, C.E. Amyloid efflux transporter expression at the blood-brain barrier declines in normal aging. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushworth, J.V.; Griffiths, H.H.; Watt, N.T.; Hooper, N.M. Prion protein-mediated toxicity of amyloid-β oligomers requires lipid rafts and the transmembrane LRP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 8935–8951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.F.; Ramasamy, R.; Schmidt, A.M. The RAGE axis: A fundamental mechanism signaling danger to the vulnerable vasculature. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 842–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takuma, K.; Fang, F.; Zhang, W.; Yan, S.; Fukuzaki, E.; Du, H.; Sosunov, A.; McKhann, G.; Funatsu, Y.; Nakamichi, N.; et al. RAGE-mediated signaling contributes to intraneuronal transport of amyloid-β and neuronal dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20021–20026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slevin, M.; Ahmed, N.; Wang, Q.; McDowell, G.; Badimon, L. Unique vascular protective properties of natural products: Supplements or future main-line drugs with significant anti-atherosclerotic potential? Vasc. Cell 2012, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazaei, M.; Karimi, J.; Sheikh, N.; Goodarzi, M.T.; Saidijam, M.; Khodadadi, I.; Moridi, H. Effects of resveratrol on receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) expression and oxidative stress in the liver of rats with type 2 diabetes. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moridi, H.; Karimi, J.; Sheikh, N.; Goodarzi, M.T.; Saidijam, M.; Yadegarazari, R.; Khazaei, M.; Khodadadi, I.; Tavilani, H.; Piri, H.; et al. Resveratrol-dependent down-regulation of receptor for advanced glycation end-products and oxidative stress in kidney of rats with diabetes. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 13, e23542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malm, T.M.; Jay, T.R.; Landreth, G.E. The evolving biology of microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Aucoin, D.; Ahmed, M.; Ziliox, M.; Van Nostrand, W.E.; Smith, S.O. Capping of Aβ42 oligomers by small molecule inhibitors. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 7893–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.A.; Saraiva, M.J.; Cardoso, I. Stability of the transthyretin molecule as a key factor in the interaction with a-β peptide-relevance in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, H.J. Protective effects of piceatannol against β-amyloid-induced neuronal cell death. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1095, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Guo, Y.; Yan, J.; Luo, Z.; Luo, H.B.; Yan, M.; Huang, L.; Li, X. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of multitarget-directed resveratrol derivatives for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 5843–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Rimando, A.; Pallas, M.; Camins, A.; Porquet, D.; Reeves, J.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Smith, M.A.; Joseph, J.A.; Casadesus, G. Low-dose pterostilbene, but not resveratrol, is a potent neuromodulator in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aprahamian, I.; Stella, F.; Forlenza, O.V. New treatment strategies for Alzheimer’s disease: Is there a hope? Indian J. Med. Res. 2013, 138, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murakami, K.; Irie, K.; Ohigashi, H.; Hara, H.; Nagao, M.; Shimizu, T.; Shirasawa, T. Formation and stabilization model of the 42-mer Aβ radical: Implications for the long-lasting oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15168–15174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabner, B.J.; El-Agnaf, O.M.; Turnbull, S.; German, M.J.; Paleologou, K.E.; Hayashi, Y.; Cooper, L.J.; Fullwood, N.J.; Allsop, D. Hydrogen peroxide is generated during the very early stages of aggregation of the amyloid peptides implicated in Alzheimer disease and familial British dementia. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 35789–35792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottart, C.H.; Nivet-Antoine, V.; Laguillier-Morizot, C.; Beaudeux, J.L. Resveratrol bioavailability and toxicity in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasinetti, G.M.; Wang, J.; Marambaud, P.; Ferruzzi, M.; Gregor, P.; Knable, L.A.; Ho, L. Neuroprotective and metabolic effects of resveratrol: Therapeutic implications for Huntington’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 232, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experimental Animal | Model/Method | Action of Resveratrol | Dosage | Duration of Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP/PS1 mice | AD | Inhibits Aβ-mediated microglial activation | AIN-93G diet supplemented with 0.35% resveratrol | 15 weeks | [15] |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | - | increases PSEN1 expression in the rat brain | dietary resveratrol | 28 days | [26] |

| Mice | Injected with lipopolysaccharide | increases both the estradiol level and NEP level | injected with resveratrol 4 mg/kg | 7 days | [27] |

| APP/transthyretin (TTR) mice | AD | Increased LRP1 expression upregulated and stabilizes TTR | 174 mg/kg/day | 2 months | [28] |

| Wistar female rats | AD | decreases level of insoluble Aβ in the hippocampus | 80 mg/kg | 12 weeks | [29] |

| reduces the expression of RAGE in the hippocampus | |||||

| inhabits the expression of MMP-9 |

| Experimental Model/Method | Exposure | Mechanism of Resveratrol | Dosage of Resveratrol | Duration of Resveratrol Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC12 cells | Aβ25–35 induced | attenuated Aβ-induced cytotoxicity, apoptotic features, and intracellular ROI accumulation. | 25 μM | 24 h | [13] |

| PC12 cells | Aβ25–35 induced | inhibited the cell apoptosis | 12.5–100 μM | 24–48 h | [14] |

| prevented the LDH leakage | |||||

| maintained the intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis | |||||

| Purified baculovirus-expressed BACE-1 | - | inhibition of BACE-1 | 11.9 μM (IC50) | - | [30] |

| TRF assay | - | inhibition of BACE-1 | 28 μM (IC50) | 30 min | [31] |

| Neuro2a cells HEK293 | transfected with a plasmid containing APPsw | reduced γ-secretase activity | 2.5–20 μM | 24 h | [32] |

| induced MMP-9 activation | |||||

| autophagy-related 5 knockdown HEK293 | - | induced conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II | 60 μM | 24 h | [33] |

| suppression of Presenilin-1 induction | |||||

| suppressed Aβ production | |||||

| SK-N-SH cells | - | induction of NEP and ACE activity | 10 μM | 4 days | [34] |

| Hippocampal samples from AD patients | AD | binds to both fibril and monomer Aβ | 1.56–100 μM | - | [35] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, X. Resveratrol and Amyloid-Beta: Mechanistic Insights. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9101122

Jia Y, Wang N, Liu X. Resveratrol and Amyloid-Beta: Mechanistic Insights. Nutrients. 2017; 9(10):1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9101122

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Yongming, Na Wang, and Xuewei Liu. 2017. "Resveratrol and Amyloid-Beta: Mechanistic Insights" Nutrients 9, no. 10: 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9101122