Grain Foods Are Contributors of Nutrient Density for American Adults and Help Close Nutrient Recommendation Gaps: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

Methods and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

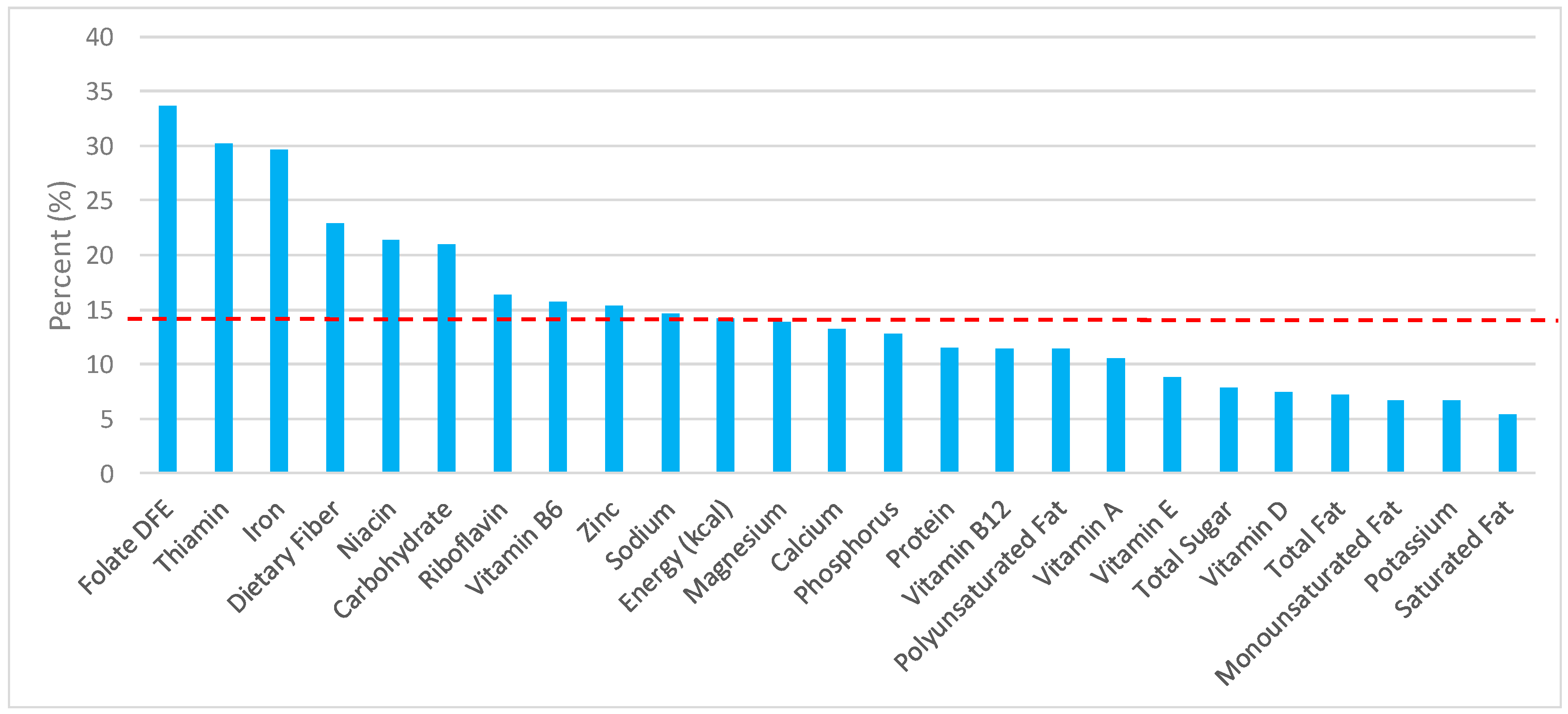

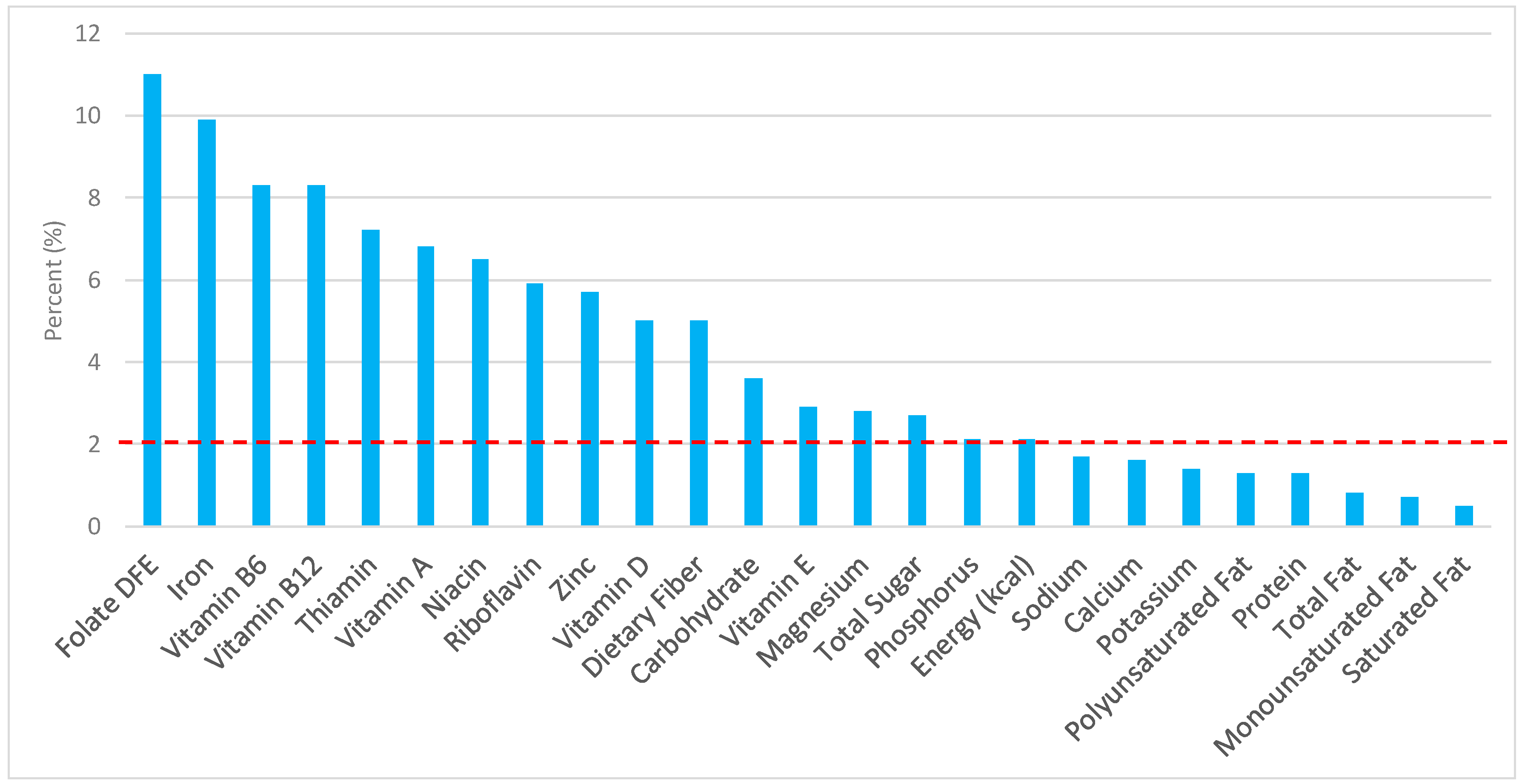

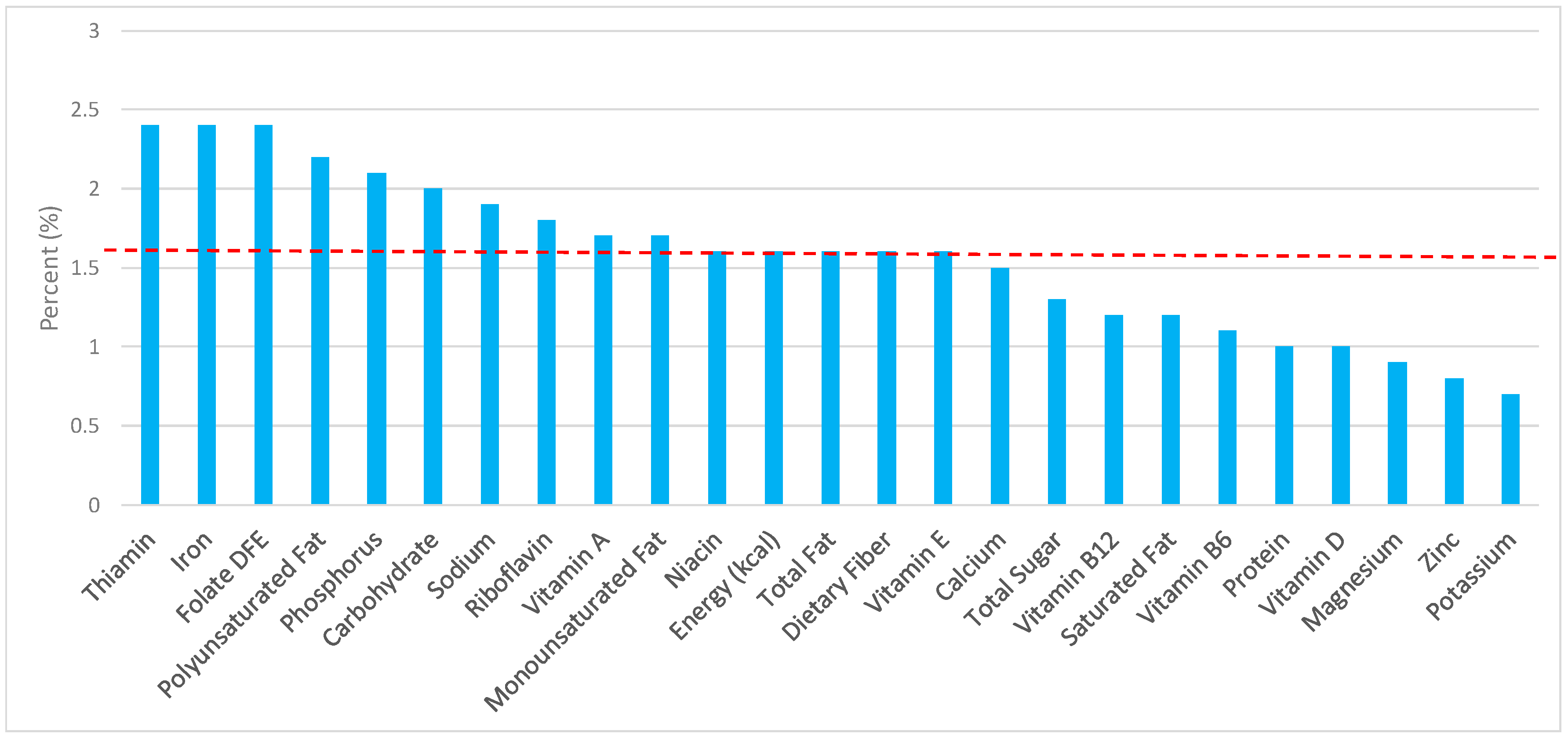

3.1. All Grain Foods: Sources of Energy and Nutrients

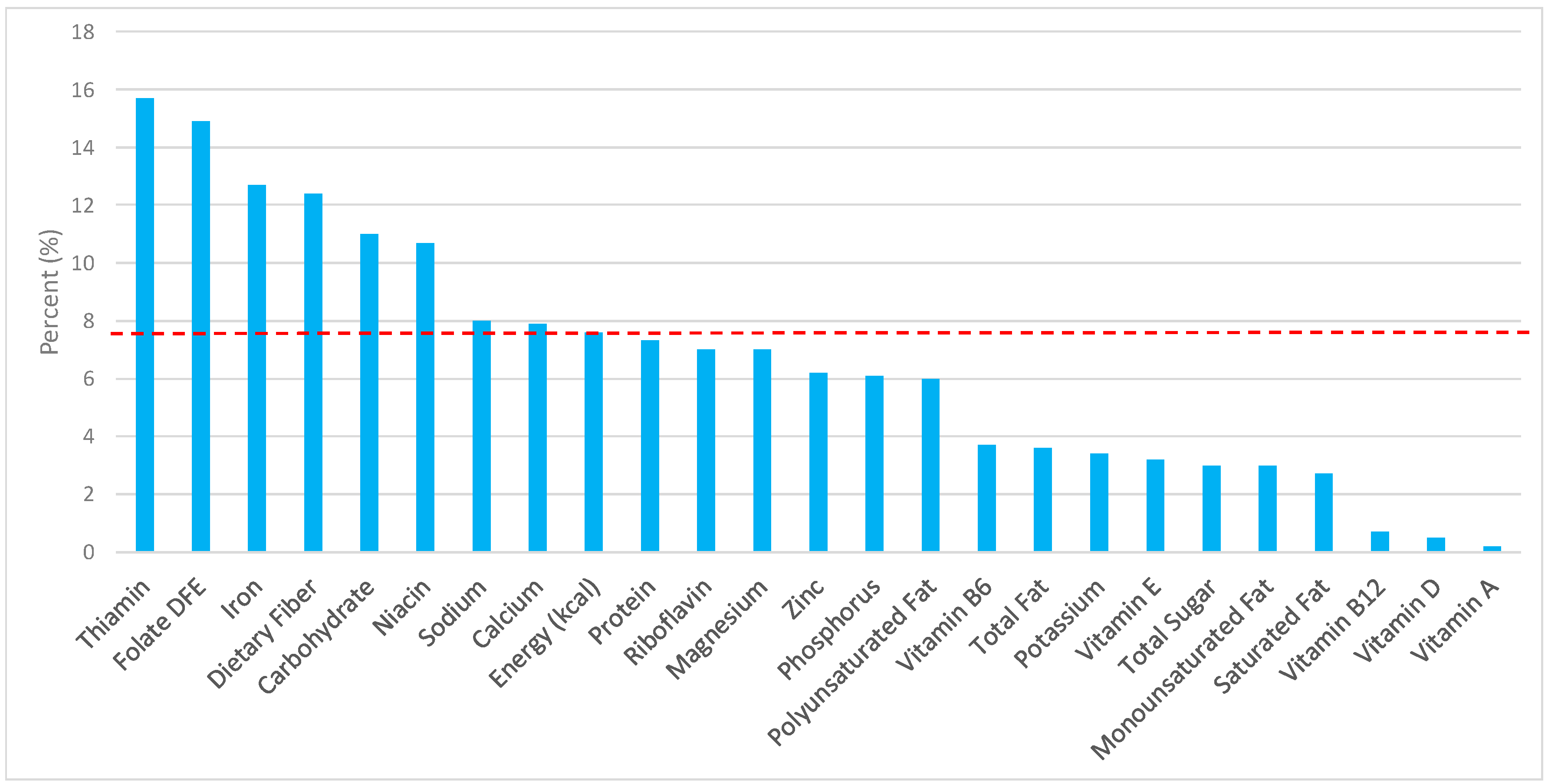

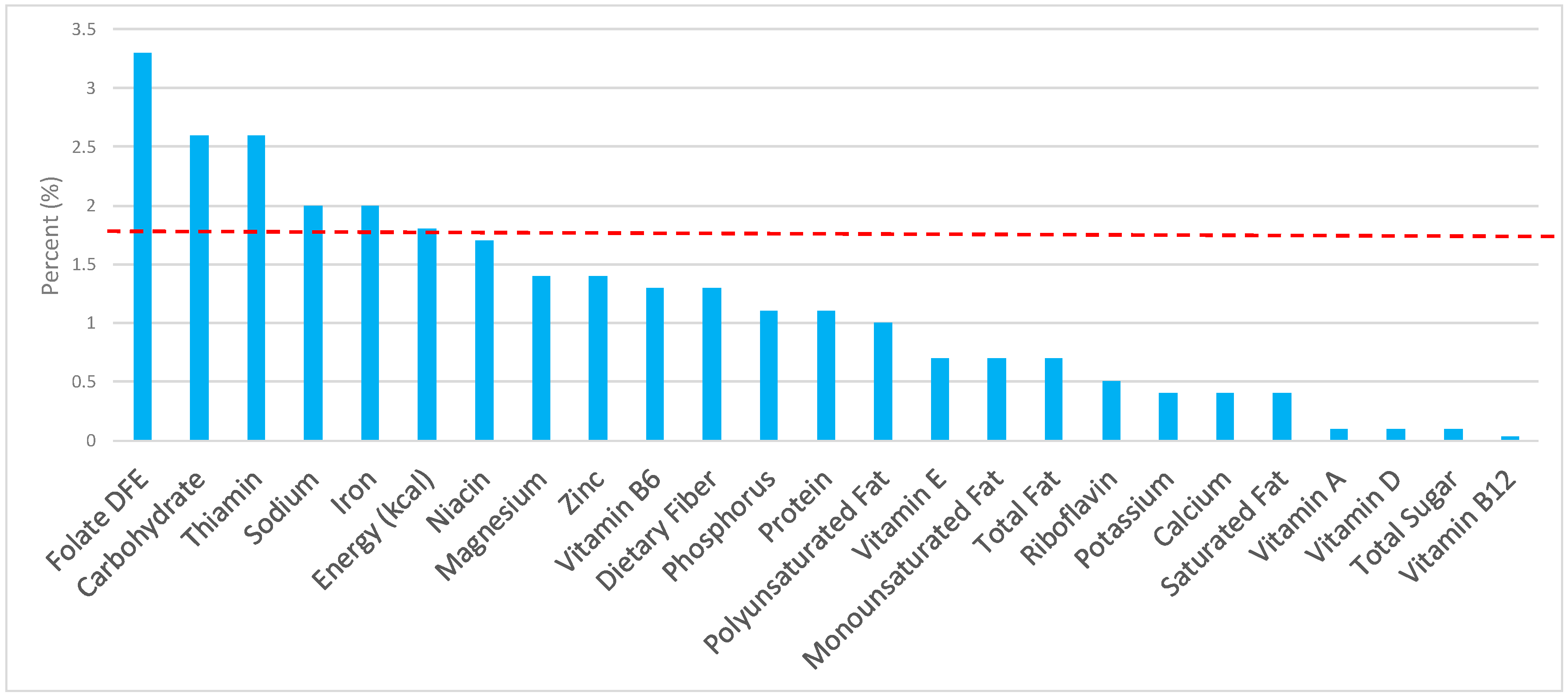

3.2. Breads, Rolls, and Tortillas: Sources of Energy and Nutrients by Gender

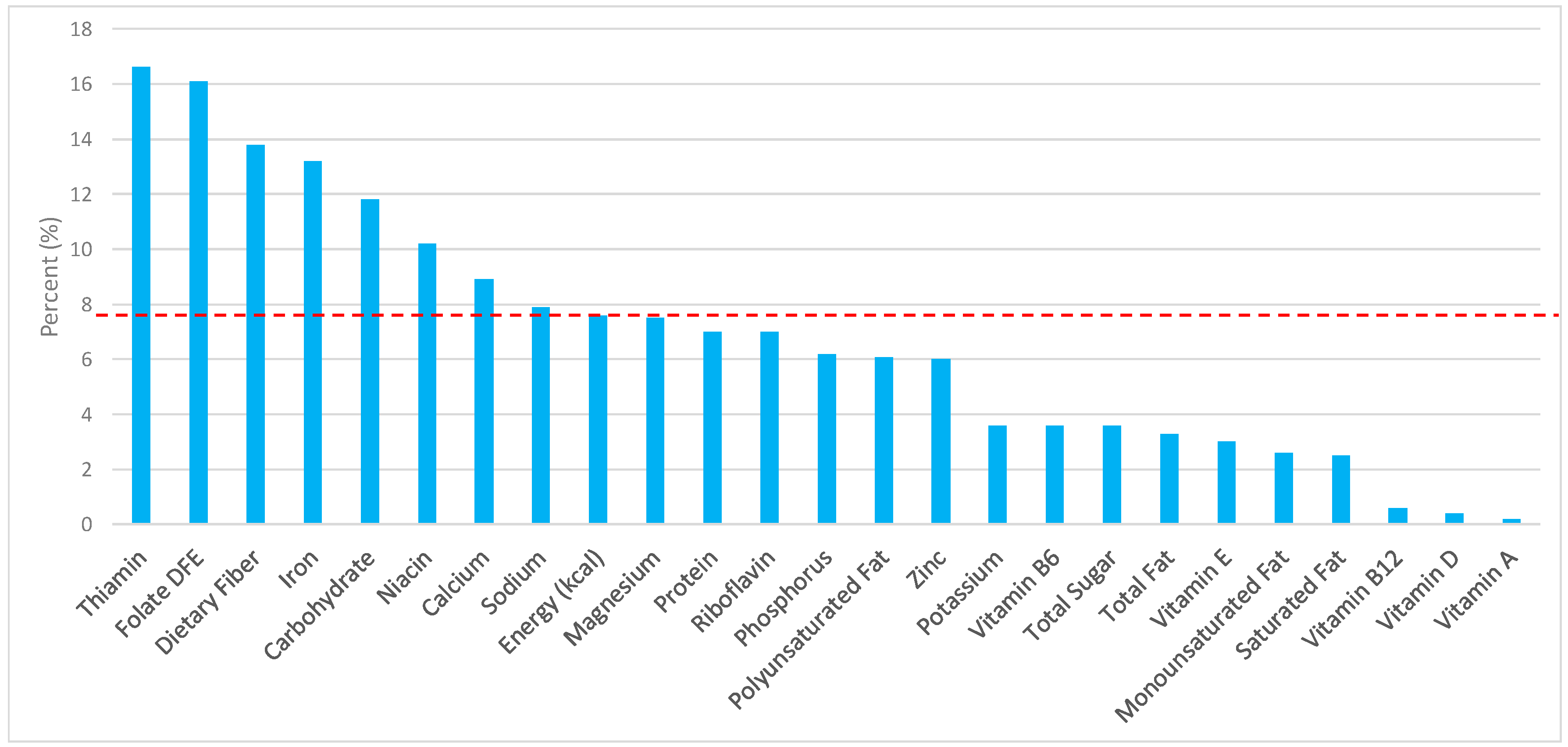

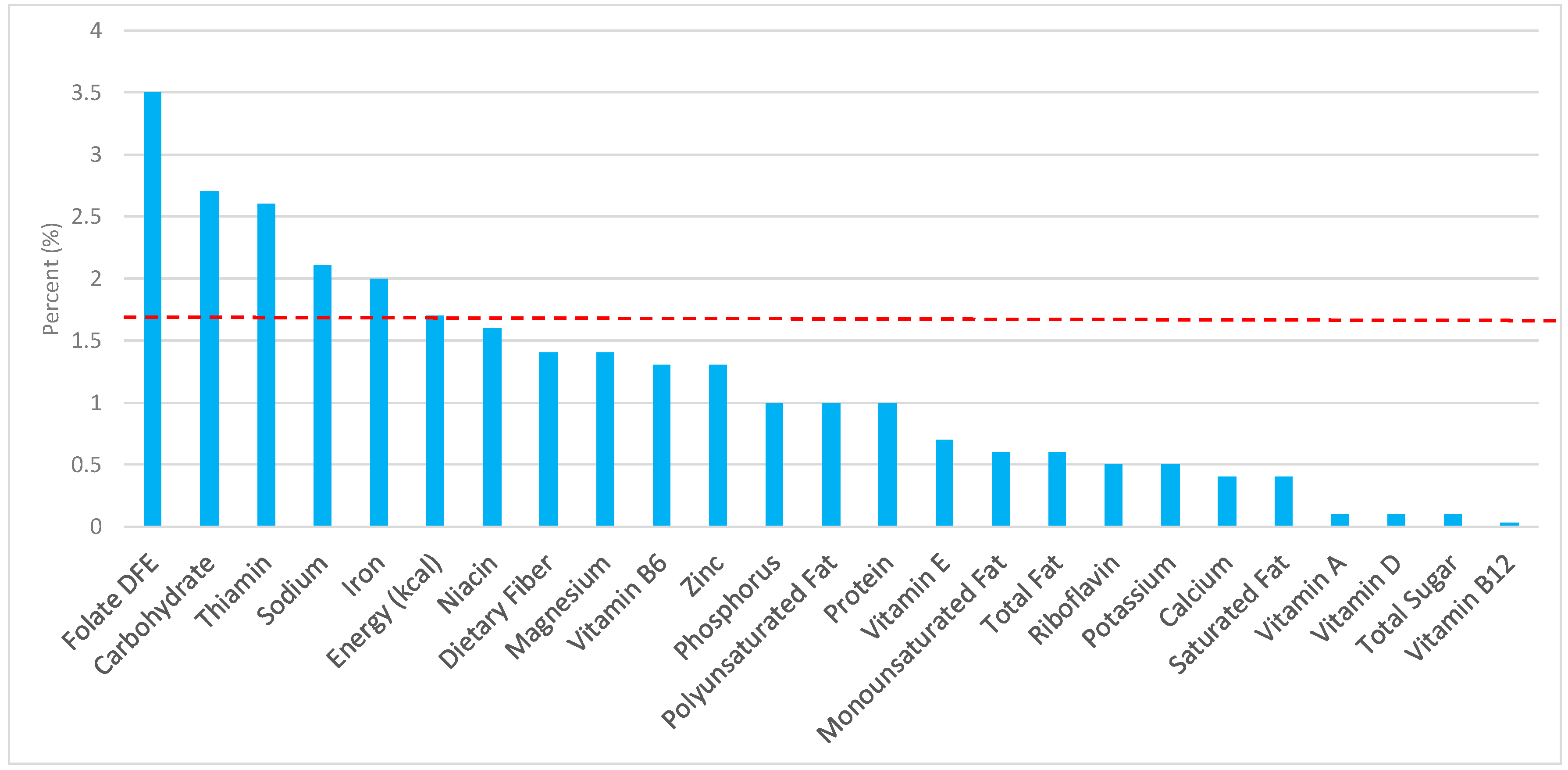

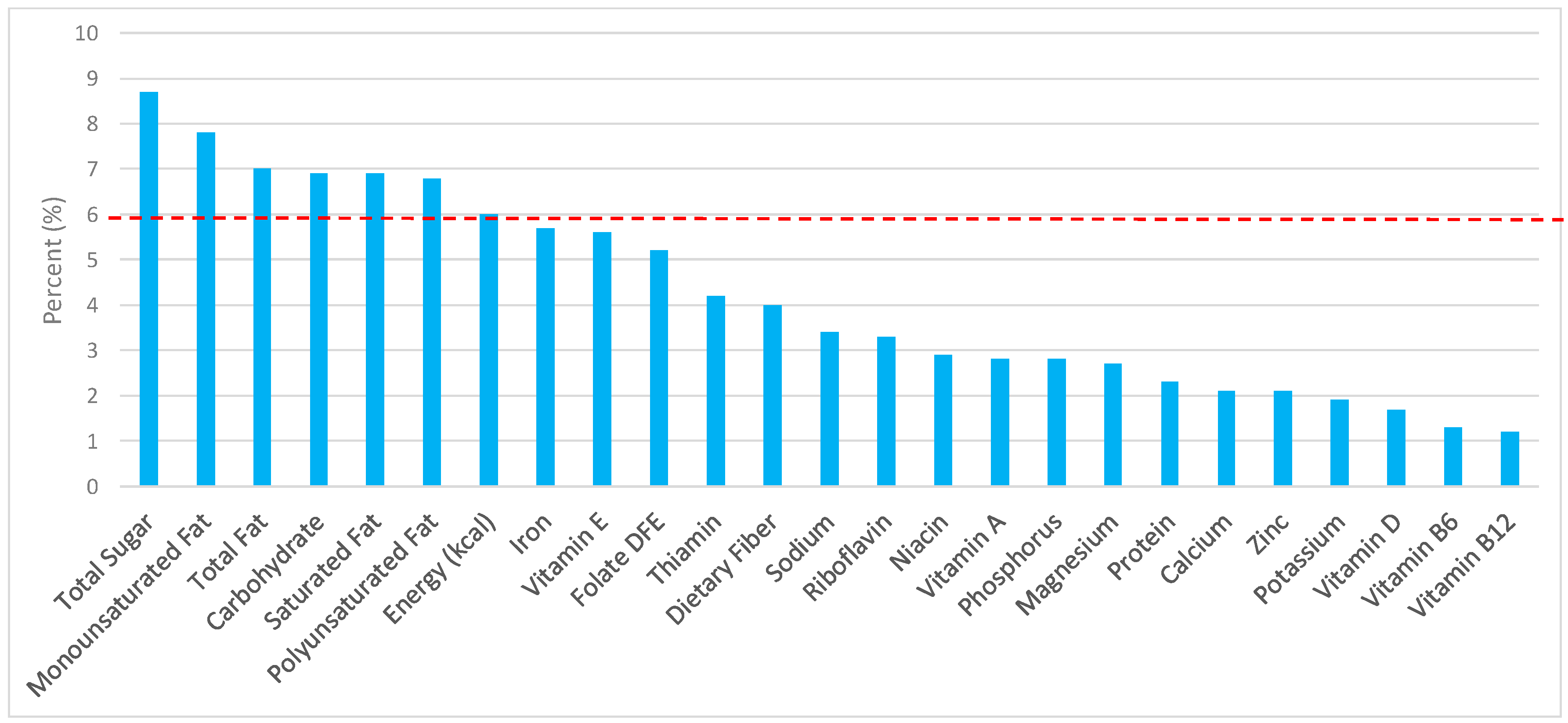

3.3. Ready-to-Eat Cereals: Sources of Energy and Nutrients by Gender

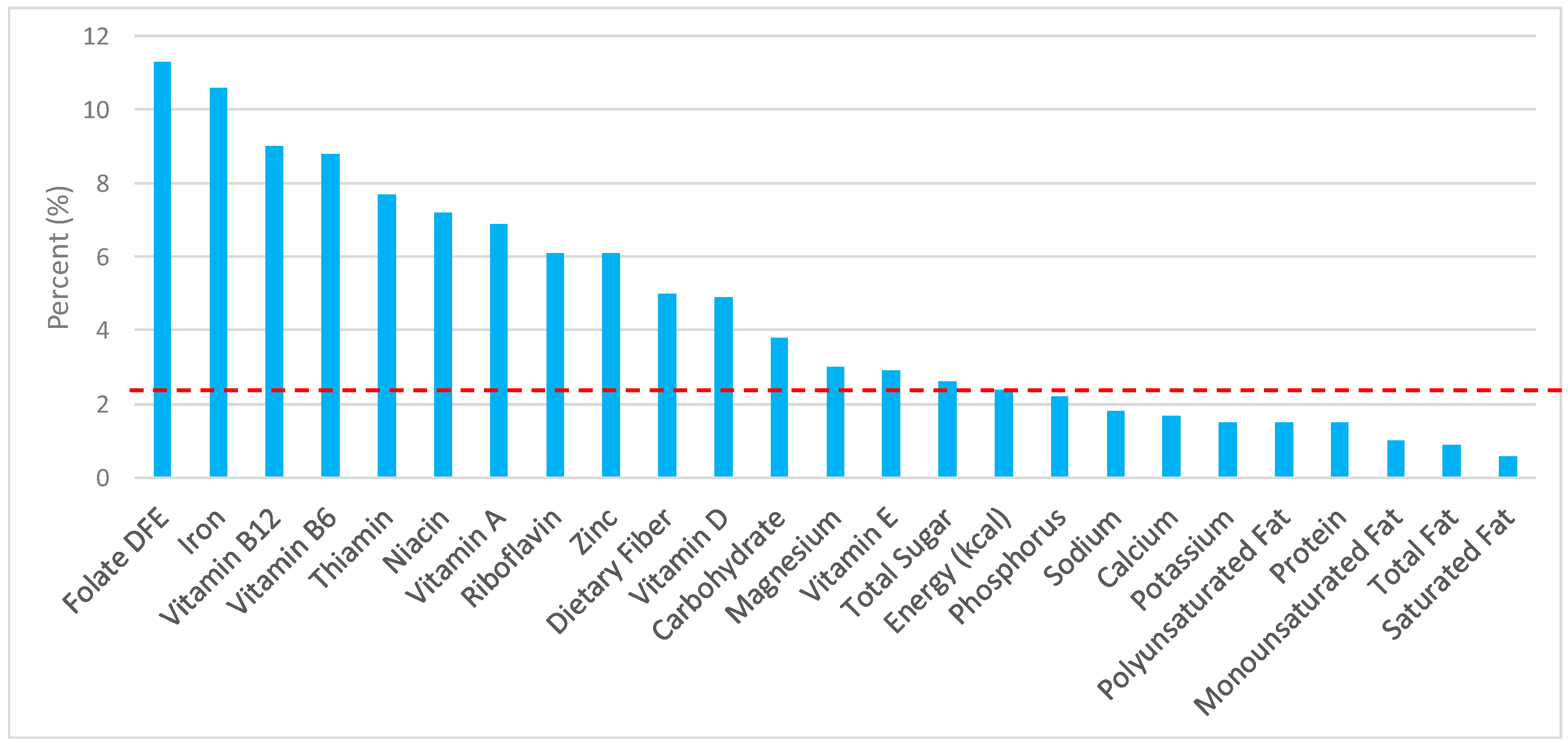

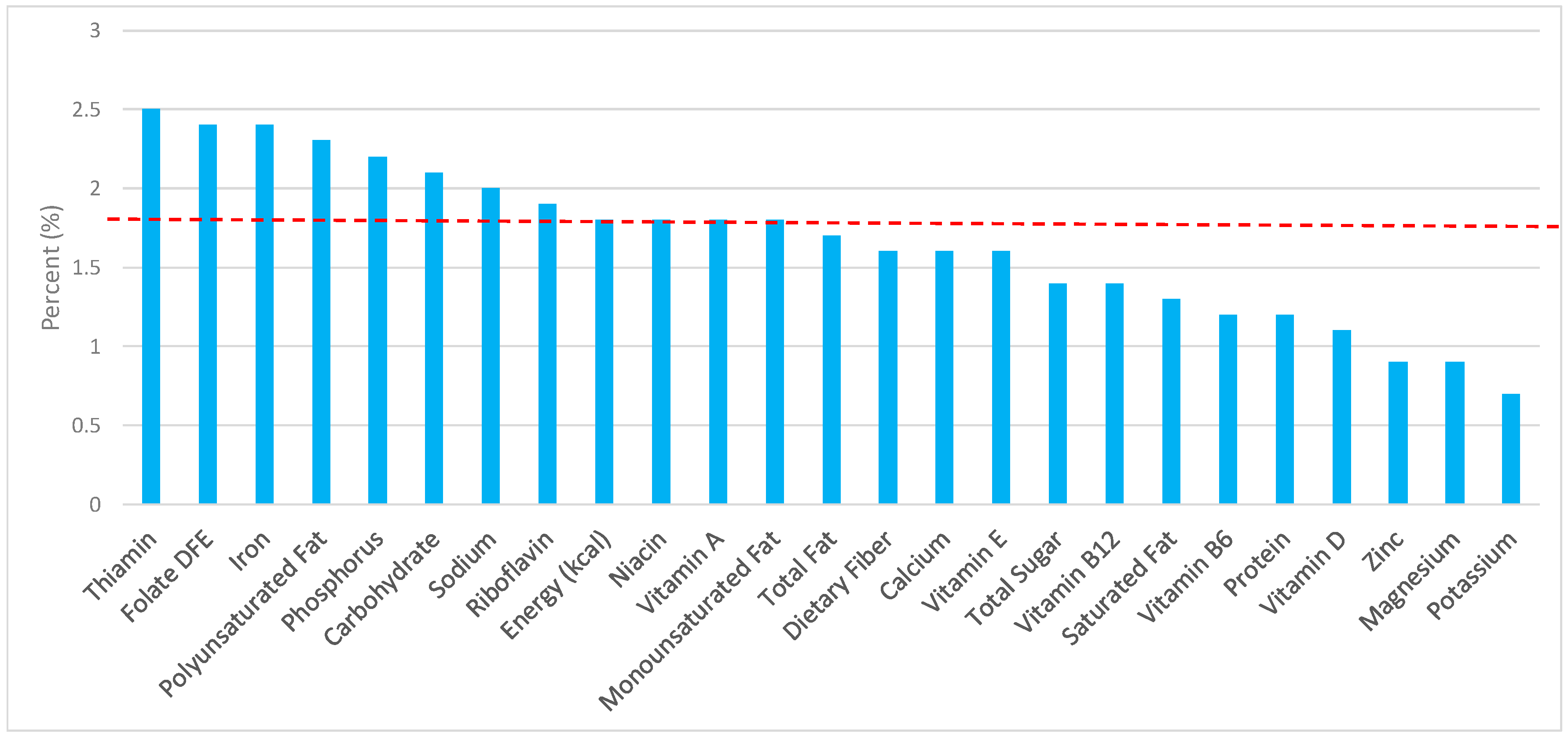

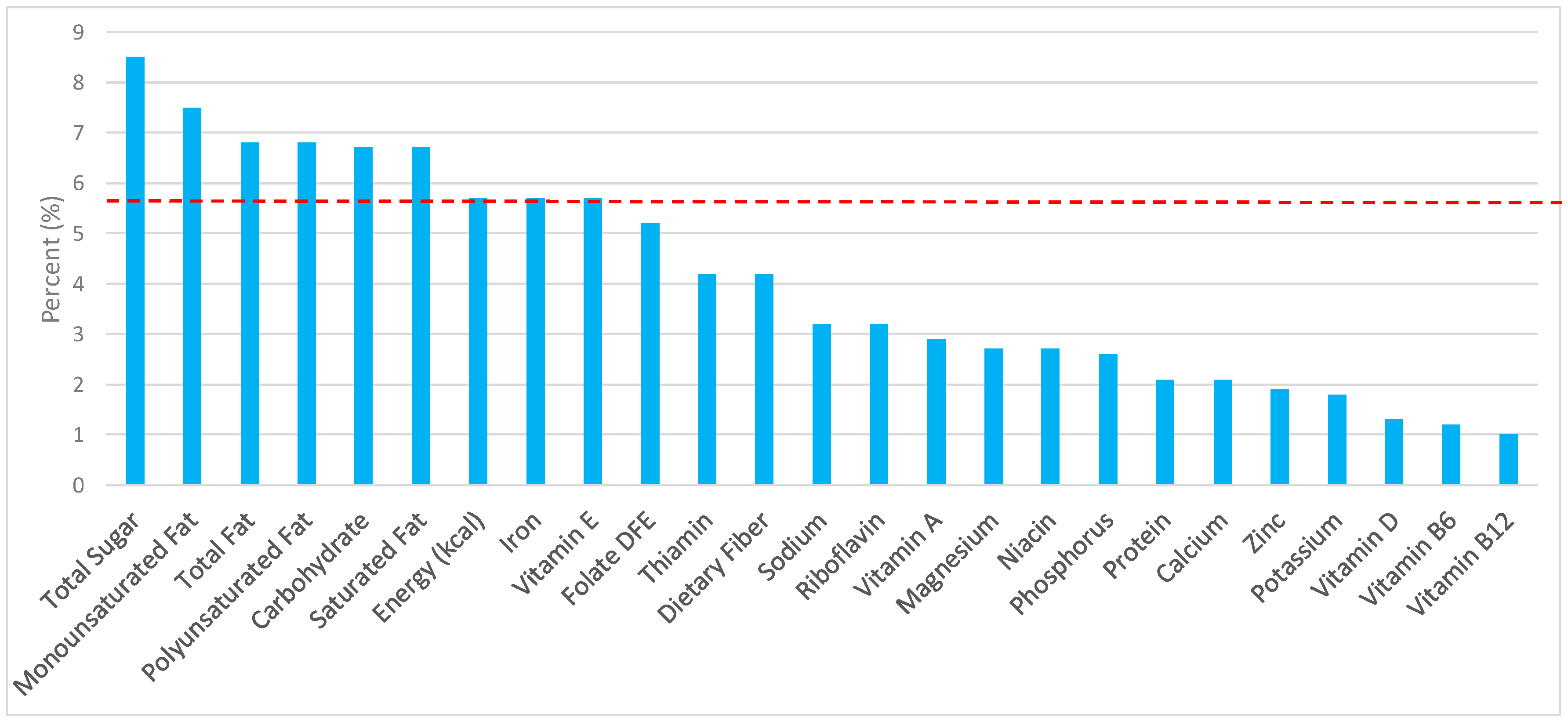

3.4. Cooked Grains: Sources of Energy and Nutrients by Gender

3.5. Quick Breads and Bread Products: Sources of Energy and Nutrients by Gender

3.6. Sweet Bakery Products: Sources of Energy and Nutrients by Gender

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Health and Human Services and United States Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed.; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/resources/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2017).

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, V.L. Certain grain food patterns are associated with improved 2015 Dietary Guidelines shortfall nutrient intakes, diet quality, and lower body weight in U.S. adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2010. Food Nutr. Sci. 2016, 7, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Miller-Jones, J.; Fulgoni, V.L. Several grain dietary patterns are associated with better diet quality and improved shortfall nutrient intakes in U.S. children and adolescents: A study focusing on the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Nutr. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Guenther, P.M.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Dodd, K.W. Americans do not meet federal dietary recommendations. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1832–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, V.L. Certain grain foods can be meaningful contributors to nutrient density in the diets of U.S. children and adolescents: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012. Nutrients 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Analytic and Reporting Guidelines. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/nhanes_analytic_guidelines_dec_2005.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2017).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Analytic Note Regarding 2007–2010 Survey Design Changes and Combining Data across other Survey Cycles. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/analyticnote_2007-2010.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2017).

- Ahuja, J.K.A.; Montville, J.B.; Omolewa-Tomobi, G.; Heendeniya, K.Y.; Martin, C.L.; Steinfeldt, L.C.; Anand, J.; Adler, M.E.; LaComb, R.P.; Moshfegh, A.J. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 5.0–Documentation and User Guide; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group: Beltsville, MD, USA, 2012.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s What We Eat in America—Food Commodity Intake Database, 2003–2008 (WWEIA-FCID 2003–2008). Available online: http://fcid.foodrisk.org (accessed on 7 June 2017).

- National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine; Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes: Recommended Intakes for Individuals. Available online: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Nutrition/DRI-Tables/5Summary%20TableTables%2014.pdf?la=en (accessed on 12 June 2017).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDA/HHS). Scientific Report of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and Secretary of Agriculture; USDA, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, 7th ed.; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Weaver, C.M.; Dwyer, J.; Fulgoni, V.L.; King, J.C.; Leveille, G.A.; MacDonald, R.S.; Ordovas, J.; Schnakenberg, D. Processed foods: Contributions to nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 1525–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.T.; Fulgoni, V.L.; Clemens, R.A.; Schmidt, D.B.; Freedman, M.R. Is “processed” a four-letter word? The role of processed foods in achieving dietary guidelines and nutrient recommendations. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppaka, R. Ten great public health achievements—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR 2011, 60, 619–623. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, R.J.; Bailey, L.; Mulinare, J.; Bower, C.; Folic Acid Working Group. Fortification of flour with folic acid. Food Nutr. Bull. 2010, 31, S22–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.T.; Wiemer, K.L.; Dary, O.; Keen, C.L.; King, J.C.; Miller, K.B.; Philbert, M.A.; Tarasuk, V.; Taylor, C.L.; Gaine, P.C.; et al. Fortification and health: Challenges and opportunities. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Guidelines on Food Fortification with Micronutrients; Allen, L., de Benoist, B., Dary, O., Hurrell, R., Eds.; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, P.J.; Fulgoni, V.L.; Keast, D.R.; Park, K.; Auestad, N. Major food sources of calories, added sugars, and saturated fat and their contribution to essential nutrient intakes in the U.S. diet: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2003–2006). Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulgoni, V.L.; Keast, D.R.; Bailey, R.L.; Dwyer, J. Foods, fortificants, and supplements: Where do Americans get their nutrients? J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keast, D.R.; Fulgoni, V.L.; Nicklas, T.A.; O’Neil, C.E. Food sources of energy and nutrients among children in the United States: NHANES 2003–2006. Nutrients 2013, 5, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulgoni, V.L.; Buckley, R.B. The contribution of fortified ready-to-eat cereal to vitamin and mineral intake in the U.S. population, NHANES 2007–2010. Nutrients 2015, 7, 3949–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.; Picciano, M.F.; Raiten, D.J. Members of the Steering Committee. Collection of food and dietary supplement intake data: What we eat in America—NHANES. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 590S–600S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Grain Food Group Category | Mean Weight (g) Consumption (SE) | Percent (%) Weight Consumption in the Total Diet |

|---|---|---|

| All Foods | 3555 ± 36 | 100 ± 0 |

| All Grains | 126.3 ± 3.0 | 4.1 ± 0.123 |

| Breads, Rolls & Tortillas | 55.7 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 0.03 |

| Ready-to-Eat Cereals | 12.2 ± 0.4 | 0.39 ± 0.01 |

| Cooked Grains | 24.6 ± 1.7 | 0.82 ± 0.06 |

| Quick Breads & Bread Products | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 0.40 ± 0.03 |

| Sweet Bakery Products | 36.0 ± 0.84 | 1.1 ± 0.03 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, V.L. Grain Foods Are Contributors of Nutrient Density for American Adults and Help Close Nutrient Recommendation Gaps: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012. Nutrients 2017, 9, 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080873

Papanikolaou Y, Fulgoni VL. Grain Foods Are Contributors of Nutrient Density for American Adults and Help Close Nutrient Recommendation Gaps: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012. Nutrients. 2017; 9(8):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080873

Chicago/Turabian StylePapanikolaou, Yanni, and Victor L. Fulgoni. 2017. "Grain Foods Are Contributors of Nutrient Density for American Adults and Help Close Nutrient Recommendation Gaps: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012" Nutrients 9, no. 8: 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080873