Recent Advances in Mycotoxin Determination for Food Monitoring via Microchip

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials of the Microchip

3. Application of Microchips for the Determination of Mycotoxins in Foods

3.1. Optical Detection

3.1.1. Fluorescence Detection

3.1.2. Chemiluminescence Detection

3.1.3. Colorimetric Detection

3.2. Electrochemical Detection

3.3. Photo-Electrochemical Detection

3.4. Label-Free Detection

3.4.1. MS Detection

3.4.2. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Detection

Microchip SPR Sensors Based on Antibodies

Microchip SPR Biosensors Based on Aptamers

Microchip SPR Biosensors Based on MIP

3.4.3. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Detection

3.4.4. Optical Waveguide Lightmode Spectroscopy (OWLS) Detection

3.4.5. Broad-Band Mach–Zehnder Interferometry (BB-MZI) Detection

3.4.6. Giant Magnetoresistive Detection

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P. Mycotoxin determination in foods using advanced sensors based on antibodies or aptamers. Toxins 2016, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, A.; Giuberti, G.; Frisvad, J.; Bertuzzi, T.; Nielsen, K. Review on mycotoxin issues in ruminants: Occurrence in forages, effects of mycotoxin ingestion on health status and animal performance and practical strategies to counteract their negative effects. Toxins 2015, 7, 3057–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kong, D.; Liu, L.; Song, S.; Suryoprabowo, S.; Li, A.; Kuang, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, C. A gold nanoparticle-based semi-quantitative and quantitative ultrasensitive paper sensor for the detection of twenty mycotoxins. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 5245–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthiller, F.; Crews, C.; Dall’Asta, C.; Saeger, S.D.; Haesaert, G.; Karlovsky, P.; Oswald, I.P.; Seefelder, W.; Speijers, G.; Stroka, J. Masked mycotoxins: A review. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Egmond, H.P.; Schothorst, R.C.; Jonker, M.A. Regulations relating to mycotoxins in food. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 389, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagnollo, F.B.; Ganev, K.C.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Portela, J.B.; Cruz, A.G.; Granato, D.; Corassin, C.H.; Oliveira, C.A.F.; Sant’Ana, A.S. The occurrence and effect of unit operations for dairy products processing on the fate of aflatoxin M1: A review. Food Control 2016, 68, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfossi, L.; Giovannoli, C.; Baggiani, C. Mycotoxin detection. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 37, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacentini, K.C.; Rocha, L.O.; Fontes, L.C.; Carnielli, L.; Reis, T.A.; Corrêa, B. Mycotoxin analysis of industrial beers from Brazil: The influence of fumonisin B1 and deoxynivalenol in beer quality. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensassi, F.; Zaied, C.; Abid, S.; Hajlaoui, M.R.; Bacha, H. Occurrence of deoxynivalenol in durum wheat in Tunisia. Food Control 2010, 21, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimany, F.; Jinap, S.; Rahmani, A.; Khatib, A. Simultaneous detection of 12 mycotoxins in cereals using RP-HPLC-PDA-FLD with PHRED and a post-column derivatization system. Food Addit. Contam. A 2011, 28, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.J.; Shen, H.H.; Zhang, X.F.; Yang, X.L.; Qiu, F.; Ou-yang, Z.; Yang, M.H. Analysis of zearalenone and α-zearalenol in 100 foods and medicinal plants determined by HPLC-FLD and positive confirmation by LC-MS-MS. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 1584–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meca, G.; Zinedine, A.; Blesa, J.; Font, G.; Mañes, J. Further data on the presence of Fusarium emerging mycotoxins enniatins, fusaproliferin and beauvericin in cereals available on the Spanish markets. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1412–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mornar, A.; Sertić, M.; Nigović, B. Development of a rapid LC/DAD/FLD/MSn method for the simultaneous determination of monacolins and citrinin in red fermented rice products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walravens, J.; Mikula, H.; Rychlik, M.; Asam, S.; Devos, T.; Njumbe Ediage, E.; Diana Di Mavungu, J.; Jacxsens, L.; Van Landschoot, A.; Vanhaecke, L.; et al. Validated UPLC-MS/MS methods to quantitate free and conjugated alternaria toxins in commercially available tomato products and fruit and vegetable juices in belgium. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 5101–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, E.; Glauner, T.; Berthiller, F.; Krska, R.; Schuhmacher, R.; Sulyok, M. Development and validation of a (semi-) quantitative UHPLC-MS/MS method for the determination of 191 mycotoxins and other fungal metabolites in almonds, hazelnuts, peanuts and pistachios. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 5087–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.C.; Zheng, N.; Zheng, B.Q.; Wen, F.; Cheng, J.B.; Han, R.W.; Xu, X.M.; Li, S.L.; Wang, J.Q. Simultaneous determination of aflatoxin M1, ochratoxin A, zearalenone and α-zearalenol in milk by UHPLC–MS/MS. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, M.; Akimoto, N.; Ohnishi, K.; Yamashita, M.; Maoka, T. Rapid and simultaneous determination of tetra cyclic peptide phytotoxins, tentoxin, isotentoxin and dihydrotentoxin, from Alternaria porri by LC/MS. Chromatogr.-Tokyo-Soc. Chromatogr. Sci. 2003, 24, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Prelle, A.; Spadaro, D.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. A new method for detection of five alternaria toxins in food matrices based on LC–APCI-MS. Food Chem. 2013, 140, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mavungu, D.; De Saeger, S. Masked mycotoxins in food and feed: Challenges and analytical approaches. In Determining Mycotoxins and Mycotoxigenic Fungi in Food and Feed; Mavungu, J.D.D., Saeger, S.D., Eds.; Woodhead: Cambridge, UK, 2011; Volume 203, pp. 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dzuman, Z.; Vaclavikova, M.; Polisenska, I.; Veprikova, Z.; Fenclova, M.; Zachariasova, M.; Hajslova, J. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in analysis of deoxynivalenol: Investigation of the impact of sample matrix on results accuracy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, R.R.G.; Novo, P.; Azevedo, A.M.; Fernandes, P.; Chu, V.; Conde, J.P.; Aires-Barros, M.R. Aqueous two-phase systems for enhancing immunoassay sensitivity: Simultaneous concentration of mycotoxins and neutralization of matrix interference. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1361, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

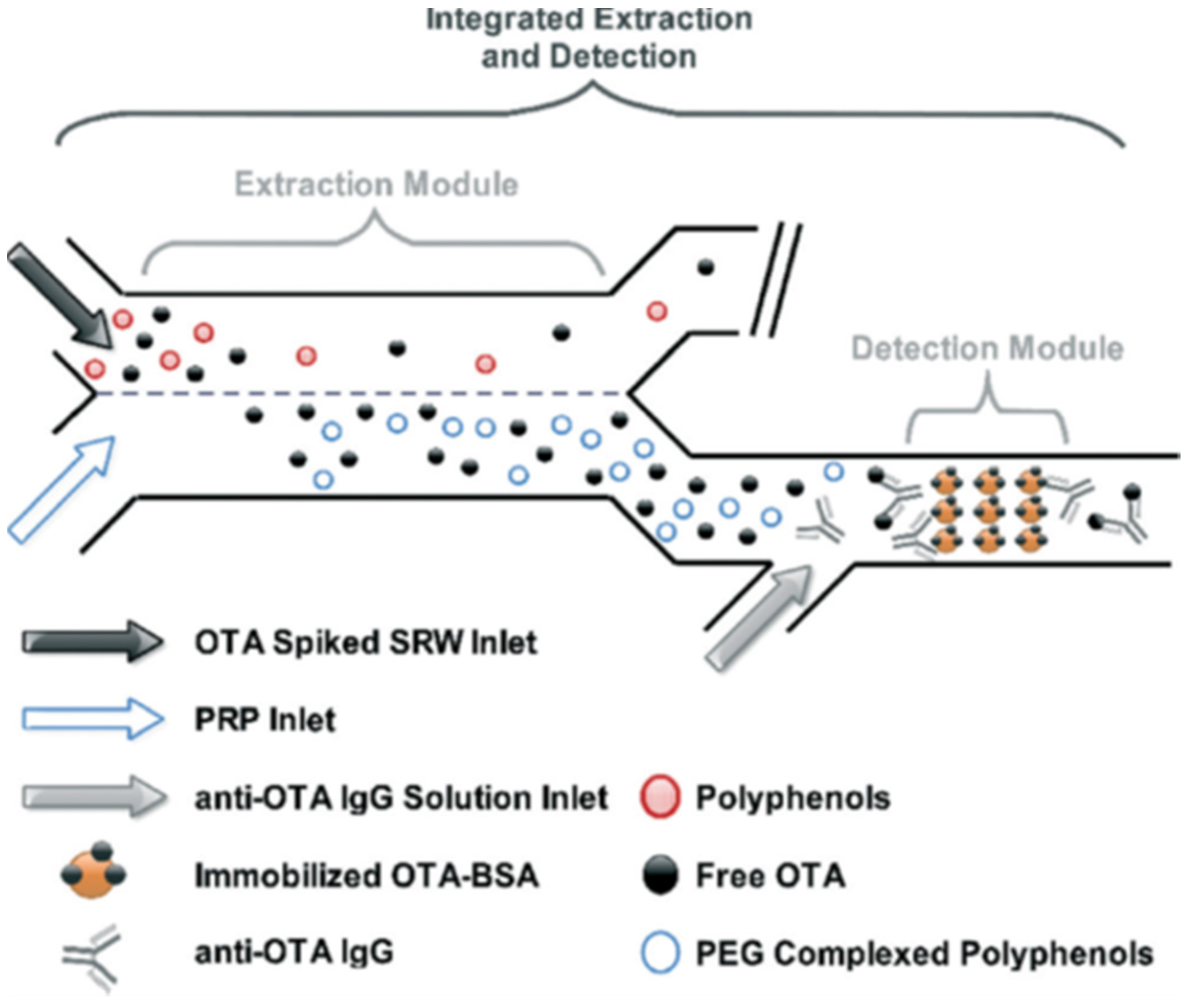

- Soares, R.R.; Novo, P.; Azevedo, A.M.; Fernandes, P.; Aires-Barros, M.R.; Chu, V.; Conde, J.P. On-chip sample preparation and analyte quantification using a microfluidic aqueous two-phase extraction coupled with an immunoassay. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 4284–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, L.; Xu, L.; Hu, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, X.; Feng, X. Biotoxin sensing in food and environment via microchip. Electrophoresis 2014, 35, 1547–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, D.; Haeberle, S.; Roth, G.; von Stetten, F.; Zengerle, R. Microfluidic lab-on-a-chip platforms: Requirements, characteristics and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1153–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.H.; Phillips, T.D.; Jolly, P.E.; Stiles, J.K.; Jolly, C.M.; Aggarwal, D. Human aflatoxicosis in developing countries: A review of toxicology, exposure, potential health consequences, and interventions. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1106–1122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.Y.; Watson, S.; Routledge, M.N. Aflatoxin exposure and associated human health effects, a review of epidemiological studies. Food Saf. 2016, 4, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Pashazadeh, P.; Hejazi, M.; de la Guardia, M.; Mokhtarzadeh, A. Recent advances in nanomaterial-mediated bio and immune sensors for detection of aflatoxin in food products. TrAC-Trend Anal. Chem. 2017, 87, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamanaka, B.T.; de Menezes, H.C.; Vicente, E.; Leite, R.S.F.; Taniwaki, M.H. Aflatoxigenic fungi and aflatoxins occurrence in sultanas and dried figs commercialized in Brazil. Food Control 2007, 18, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, R.; Hmaissia-khlifa, K.; Ghorbel, H.; Maaroufi, K.; Hedili, A. Incidence of aflatoxins, ochratoxin A and zearalenone in tunisian foods. Food Control 2008, 19, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans. Some traditional herbal medicines, some mycotoxins, naphthalene and styrene. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 2002, 82, 1–556. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, P.; Dong, W.; Qi, Y.; Guo, H. Etiological role of alternaria alternata in human esophageal cancer. Chin. Med. J.-Peking 1992, 105, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Man, Y.; Liang, G.; Li, A.; Pan, L. Analytical methods for the determination of Alternaria mycotoxins. Chromatographia 2017, 80, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejdovszky, K.; Warth, B.; Sulyok, M.; Marko, D. Non-synergistic cytotoxic effects of Fusarium and Alternaria toxin combinations in Caco-2 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 241, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahlke, G.; Tiessen, C.; Domnanich, K.; Kahle, N.; Groh, I.A.; Schreck, I.; Weiss, C.; Marko, D. Impact of Alternaria toxins on CYP1A1 expression in different human tumor cells and relevance for genotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 240, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostry, V. Alternaria mycotoxins: An overview of chemical characterization, producers, toxicity, analysis and occurrence in foodstuffs. World Mycotoxin J. 2008, 1, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, L.; Vazquez, D. Differences in eukaryotic ribosomes detected by the selective action of an antibiotic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1973, 319, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Qiang, S. Environmental, genetic and cellular toxicity of tenuazonic acid isolated from Alternaira alternata. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, D.B.; Seitz, L.M.; Burroughs, R.; Mohr, H.E.; West, J.L.; Milleret, R.J.; Anthony, H.D. Toxicity of Alternaria metabolites found in weathered sorghum grain at harvest. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1978, 26, 1380–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meulenberg, E.P. Immunochemical methods for ochratoxin A detection: A review. Toxins 2012, 4, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A. Ochratoxin A: General overview and actual molecular status. Toxins 2010, 2, 461–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, R.; Singh, J.; Sachdev, T.; Basu, T.; Malhotra, B.D. Recent advances in mycotoxins detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 81, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekaert, N.; Devreese, M.; Demeyere, K.; Berthiller, F.; Michlmayr, H.; Varga, E.; Adam, G.; Meyer, E.; Croubels, S. Comparative in vitro cytotoxicity of modified deoxynivalenol on porcine intestinal epithelial cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 95, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, M.; Roux, J.; Mounien, L.; Dallaporta, M.; Troadec, J.D. Advances in Deoxynivalenol toxicity mechanisms: The brain as a target. Toxins 2012, 4, 1120–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pestka, J.J. Deoxynivalenol: Toxicity, mechanisms and animal health risks. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007, 137, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueza, I.; Raspantini, P.; Raspantini, L.; Latorre, A.; Górniak, S. Zearalenone, an estrogenic mycotoxin, is an immunotoxic compound. Toxins 2014, 6, 1080–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zinedine, A.; Soriano, J.M.; Moltó, J.C.; Mañes, J. Review on the toxicity, occurrence, metabolism, detoxification, regulations and intake of zearalenone: An oestrogenic mycotoxin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puel, O.; Galtier, P.; Oswald, I. Biosynthesis and toxicological effects of Patulin. Toxins 2010, 2, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Melo, F.T.; de Oliveira, I.M.; Greggio, S.; Dacosta, J.C.; Guecheva, T.N.; Saffi, J.; Henriques, J.A.P.; Rosa, R.M. DNA damage in organs of mice treated acutely with patulin, a known mycotoxin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3548–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, J.; Miller, J.D.; Trenholm, L. Mycotoxins in grain: Compounds other than aflatoxin. New Zeal. J. Crop. Hort. 1995, 23, 233–234. [Google Scholar]

- Visconti, A.; Lattanzio, V.M.T.; Pascale, M.; Haidukowski, M. Analysis of T-2 and HT-2 toxins in cereal grains by immunoaffinity clean-up and liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1075, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudakin, D.L. Trichothecenes in the environment: Relevance to human health. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 143, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfossi, L.; Calderara, M.; Baggiani, C.; Giovannoli, C.; Arletti, E.; Giraudi, G. Development and application of a quantitative lateral flow immunoassay for fumonisins in maize. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 682, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edite Bezerra da Rocha, M.; Freire, F.D.C.O.; Erlan Feitosa Maia, F.; Izabel Florindo Guedes, M.; Rondina, D. Mycotoxins and their effects on human and animal health. Food Control 2014, 36, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.R.; Colvin, B.M.; Greene, J.T.; Newman, L.E.; Cole, J.R., Jr. Pulmonary edema and hydrothorax in swine produced by fumonisin B1, a toxic metabolite of Fusarium moniliforme. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1990, 2, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Xiong, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Tu, Z.; Fu, J.; Tang, X. Citrinin detection using phage-displayed anti-idiotypic single-domain antibody for antigen mimicry. Food Chem. 2015, 177, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flajs, D.; Peraica, M. Toxicological properties of citrinin. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2009, 60, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovdisova, I.; Zbynovska, K.; Kalafova, A.; Capcarova, M. Toxicological properties of mycotoxin Citrinin. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2016, 5, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawod, M.; Arvin, N.E.; Kennedy, R.T. Recent advances in protein analysis by capillary and microchip electrophoresis. Analyst 2017, 142, 1847–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt Shields, C., IV; Reyes, C.D.; Lopez, G.P. Microfluidic cell sorting: A review of the advances in the separation of cells from debulking to rare cell isolation. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 1230–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, W.; Han, J.; Choi, J.-W.; Ahn, C.H. Point-of-care testing (POCT) diagnostic systems using microfluidic lab-on-a-chip technologies. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 132, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetala, K.K.; Vijayalakshmi, M. A review on recent developments for biomolecule separation at analytical scale using microfluidic devices. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 906, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitesides, G.M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, G.; Li, C.; Su, H. Microfluidic aqueous two-phase extraction of bisphenol A using ionic liquid for high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 3617–3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, I.F.; Caneira, C.R.F.; Soares, R.R.G.; Madaboosi, N.; Aires-Barros, M.R.; Conde, J.P.; Azevedo, A.M.; Chu, V. The application of microbeads to microfluidic systems for enhanced detection and purification of biomolecules. Methods 2017, 116, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbulovic-Nad, I.; Lucente, M.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wheeler, A.R.; Bussmann, M. Bio-microarray fabrication techniques—A review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2006, 26, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, K.; Zhou, J.; Wu, H. Materials for microfluidic chip fabrication. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2396–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollier, E.; Murray, C.; Maoddi, P.; Di Carlo, D. Rapid prototyping polymers for microfluidic devices and high pressure injections. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 3752–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Perera, A.P.; Wong, C.C.; Park, M.K. Solid phase nucleic acid extraction technique in a microfluidic chip using a novel non-chaotropic agent: Dimethyl adipimidate. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuefeng, Y.; Hong, S.; Zhaolun, F. A simplified microfabrication technology for production of glass microfluidic chips. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2003, 31, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Xu, Z.; Pan, Y.; Liu, J.; Du, L. An effective PDMS microfluidic chip for chemiluminescence detection of cobalt (II) in water. Microsyst. Technol. 2013, 19, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Li, T.Y.; Zhang, S.; Yao, Z.; Chen, X.D.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.L. Research on optimizing parameters of thermal bonding technique for PMMA microfluidic chip. Int. Polym. Proc. 2017, 32, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, S.; Holzer, R.; Renaud, P. Polyimide-based microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 2001, 1, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Hu, Z. An effective method for fabricating microchannels on the polycarbonate (PC) substrate with CO2 laser. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Kodzius, R.; Foulds, I.G. Fabrication of polystyrene microfluidic devices using a pulsed CO2 laser system. Microsyst. Technol. 2012, 18, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.M.; Liu, C.; Qiao, H.C.; Zhu, L.Y.; Chen, G.; Dai, X.D. Hot embossing/bonding of a poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) microfluidic chip. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2008, 18, 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swickrath, M.J.; Shenoy, S.; Mann, J.A.; Belcher, J.; Kovar, R.; Wnek, G.E. The design and fabrication of autonomous polymer-based surface tension-confined microfluidic platforms. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2008, 4, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.S.; Ohlsson, P.D.; Ordeig, O.; Kutter, J.P. Cyclic olefin polymers: Emerging materials for lab-on-a-chip applications. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2010, 9, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Dai, W.; Zhou, J.; Su, J.; Wu, H. Whole-Teflon microfluidic chips. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8162–8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yuen, K.T.; Mak, A.F.T.; Yang, M.; Leung, P. A polyethylene glycol (PEG) microfluidic chip with nanostructures for bacteria rapid patterning and detection. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2009, 154, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.-J.; Mak, A.F.-T.; Li, Y.; Yang, M. A microfluidic chip with poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel microarray on nanoporous alumina membrane for cell patterning and drug testing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 143, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abgrall, P.; Conedera, V.; Camon, H.; Gue, A.M.; Nguyen, N.T. SU-8 as a structural material for labs-on-chips and microelectromechanical systems. Electrophoresis 2007, 28, 4539–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wägli, P.; Homsy, A.; de Rooij, N.F. Norland optical adhesive (NOA81) microchannels with adjustable wetting behavior and high chemical resistance against a range of mid-infrared-transparent organic solvents. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 156, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, E.; Furukawa, K.S.; Miyata, F.; Sakai, Y.; Ushida, T.; Fujii, T. Fabrication of microstructures in photosensitive biodegradable polymers for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 4683–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, A.W.; Phillips, S.T.; Whitesides, G.M.; Carrilho, E. Diagnostics for the developing world: Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabinyc, M.L.; Chiu, D.T.; McDonald, J.C.; Stroock, A.D.; Christian, J.F.; Karger, A.M.; Whitesides, G.M. An integrated fluorescence detection system in poly (dimethylsiloxane) for microfluidic applications. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 4491–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Deng, Y.J.; Zou, J. Microfluidic smectite-polymer nanocomposite strip sensor for Aflatoxin detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 1835–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; He, Q.; Tu, Z.; Fu, J.; Gee, S.J.; Hammock, B.D. Anti-idiotypic nanobody-alkaline phosphatase fusion proteins: Development of a one-step competitive enzyme immunoassay for fumonisin B1 detection in cereal. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 924, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Clarke, J.R.; Marquardt, R.R.; Frohlich, A.A. Improved methods for conjugating selected mycotoxins to carrier proteins and dextran for immunoassays. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1995, 43, 2092–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

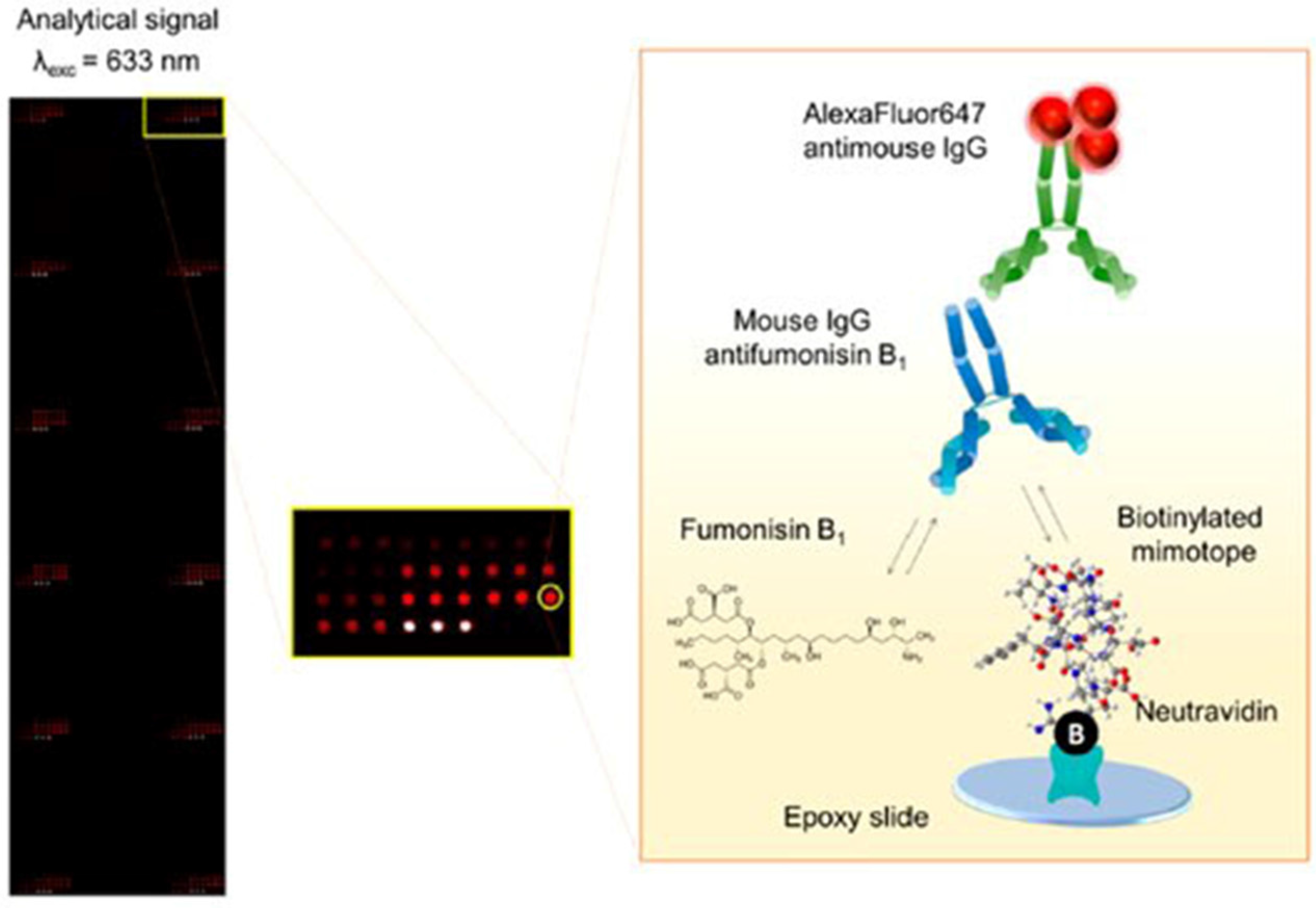

- Peltomaa, R.; Benito-Peña, E.; Barderas, R.; Sauer, U.; González Andrade, M.; Moreno-Bondi, M.C. Microarray-based immunoassay with synthetic mimotopes for the detection of fumonisin B1. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 6216–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngundi, M.M.; Shriver-Lake, L.C.; Moore, M.H.; Lassman, M.E.; Ligler, F.S.; Taitt, C.R. Array biosensor for detection of Ochratoxin A in cereals and beverages. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngundi, M.M.; Qadri, S.A.; Wallace, E.V.; Moore, M.H.; Lassman, M.E.; Shriver-Lake, L.C.; Ligler, F.S.; Taitt, C.R. Detection of Deoxynivalenol in foods and indoor air using an array biosensor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 2352–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Ning, B.; Liu, M.; Lv, Z.; Sun, Z.; Peng, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Gao, Z. Simultaneous and rapid detection of six different mycotoxins using an immunochip. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2012, 34, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Shen, P.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, T. Aptamer fluorescence signal recovery screening for multiplex mycotoxins in cereal samples based on photonic crystal microsphere suspension array. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 248, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukagoshi, K.; Jinno, N.; Nakajima, R. Development of a micro total analysis system incorporating chemiluminescence detection and application to detection of cancer markers. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeyens, W.; Schulman, S.; Calokerinos, A.C.; Zhao, Y.; Campana, A.M.G.; Nakashima, K.; De Keukeleire, D. Chemiluminescence-based detection: Principles and analytical applications in flowing streams and in immunoassays. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 1998, 17, 941–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauceda-Friebe, J.C.; Karsunke, X.Y.Z.; Vazac, S.; Biselli, S.; Niessner, R.; Knopp, D. Regenerable immuno-biochip for screening ochratoxin A in green coffee extract using an automated microarray chip reader with chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 689, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, S.; Dietrich, R.; Märtlbauer, E.; Niessner, R.; Knopp, D. Microarray-based immunoassay for parallel quantification of multiple mycotoxins in oat. Oat 2017, 1536, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

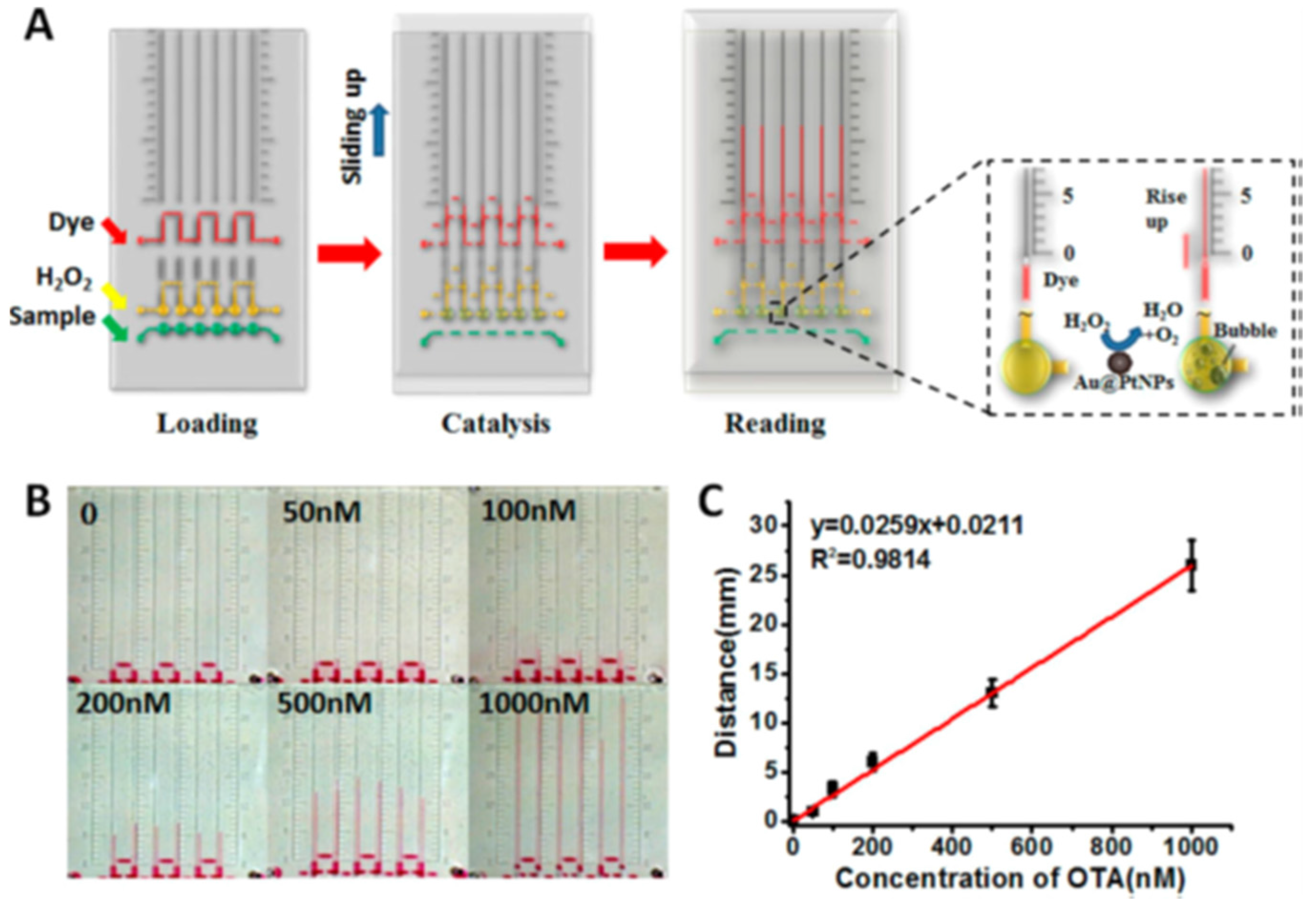

- Liu, R.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Jia, S.; Gao, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, D.; Wu, M.; Chen, Y. Design and synthesis of target-responsive aptamer-cross-linked hydrogel for visual quantitative detection of Ochratoxin A. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 2015, 7, 6982–6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Mao, Y.; Huang, D.; He, Z.; Yan, J.; Tian, T.; Shi, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Yang, C.J. Portable visual quantitative detection of aflatoxin B1 using a target-responsive hydrogel and a distance-readout microfluidic chip. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 3097–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, F.; Wong, J.X.; Yu, H.-Z. Integrated smartphone-app-chip system for on-site ppb-level colorimetric quantitation of aflatoxins. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 8908–8916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervás, M.; López, M.A.; Escarpa, A. Electrochemical immunosensing on board microfluidic chip platforms. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 31, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Meng, S.; Guo, K.; Liu, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhong, W.; Liu, B. Microfluidic immunosensor based on stable antibody-patterned surface in PMMA microchip. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piermarini, S.; Micheli, L.; Ammida, N.H.S.; Palleschi, G.; Moscone, D. Electrochemical immunosensor array using a 96-well screen-printed microplate for aflatoxin B1 detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2007, 22, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parker, C.O.; Lanyon, Y.H.; Manning, M.; Arrigan, D.W.; Tothill, I.E. Electrochemical immunochip sensor for aflatoxin M1 detection. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 5291–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arévalo, F.J.; Granero, A.M.; Fernández, H.; Raba, J.; Zón, M.A. Citrinin (CIT) determination in rice samples using a micro fluidic electrochemical immunosensor. Talanta 2011, 83, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

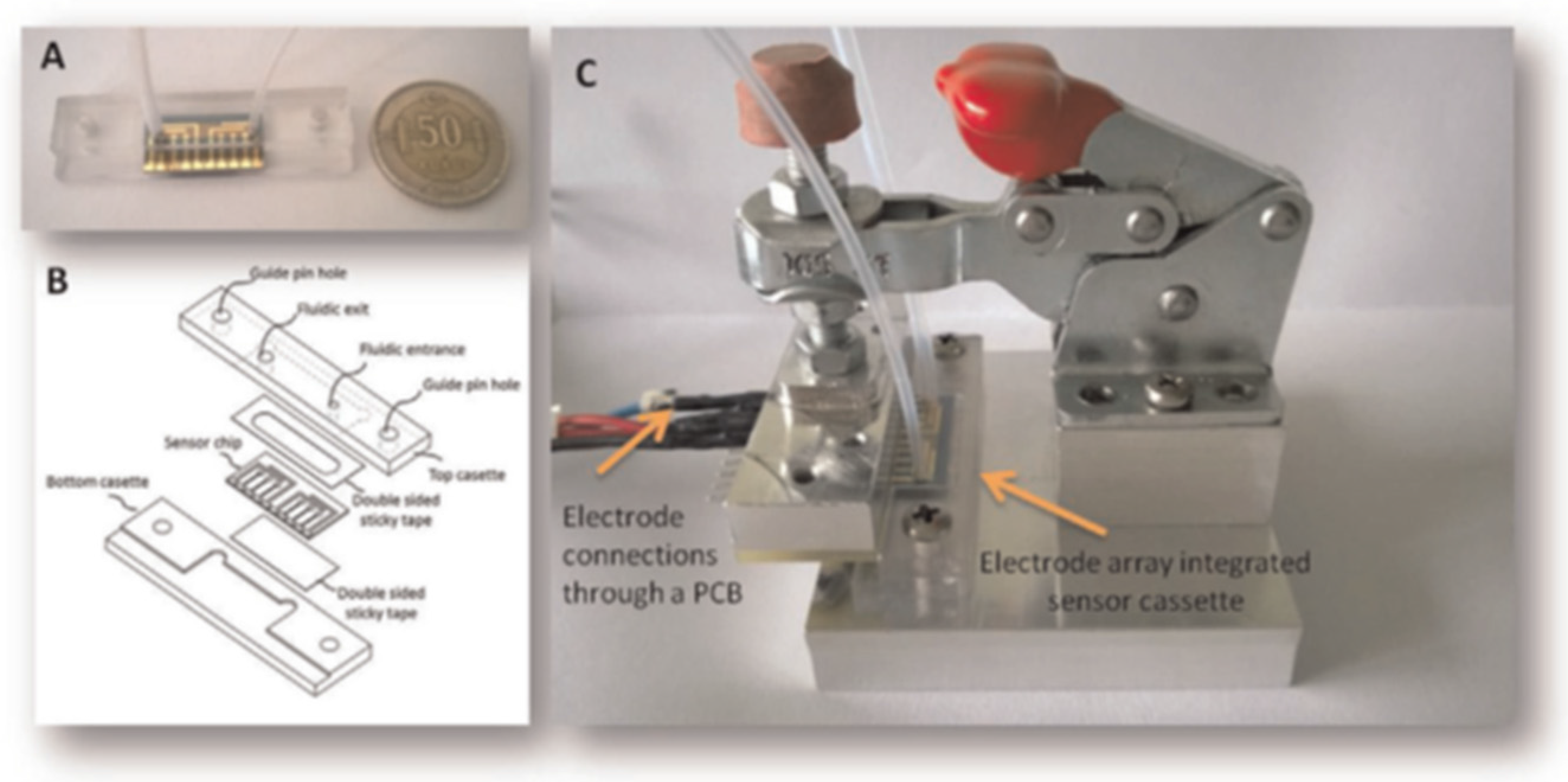

- Olcer, Z.; Esen, E.; Muhammad, T.; Ersoy, A.; Budak, S.; Uludag, Y. Fast and sensitive detection of mycotoxins in wheat using microfluidics based Real-time Electrochemical Profiling. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 62, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uludag, Y.; Esen, E.; Kokturk, G.; Ozer, H.; Muhammad, T.; Olcer, Z.; Basegmez, H.I.O.; Simsek, S.; Barut, S.; Gok, M.Y. Lab-on-a-chip based biosensor for the real-time detection of aflatoxin. Talanta 2016, 160, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervas, M.; Lopez, M.A.; Escarpa, A. Electrochemical microfluidic chips coupled to magnetic bead-based ELISA to control allowable levels of zearalenone in baby foods using simplified calibration. Analyst 2009, 134, 2405–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervas, M.; Lopez, M.A.; Escarpa, A. Integrated electrokinetic magnetic bead-based electrochemical immunoassay on microfluidic chips for reliable control of permitted levels of zearalenone in infant foods. Analyst 2011, 136, 2131–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panini, N.V.; Salinas, E.; Messina, G.A.; Raba, J. Modified paramagnetic beads in a microfluidic system for the determination of zearalenone in feedstuffs samples. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Baldo, M.A.; Bertolino, F.A.; Fernandez, G.; Messina, G.A.; Sanz, M.I.; Raba, J. Determination of Ochratoxin A in apples contaminated with Aspergillus ochraceus by using a microfluidic competitive immunosensor with magnetic nanoparticles. Analyst 2011, 136, 2756–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vistas, C.R.; Soares, S.S.; Rodrigues, R.M.; Chu, V.; Conde, J.P.; Ferreira, G.N. An amorphous silicon photodiode microfluidic chip to detect nanomolar quantities of HIV-1 virion infectivity factor. Analyst 2014, 139, 3709–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputo, D.; Cesare, G.D.; Dolci, L.S.; Mirasoli, M.; Nascetti, A.; Roda, A.; Scipinotti, R. Microfluidic chip with integrated a-Si:H photodiodes for chemiluminescence-based bioassays. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 2595–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirasoli, M.; Nascetti, A.; Caputo, D.; Zangheri, M.; Scipinotti, R.; Cevenini, L.; de Cesare, G.; Roda, A. Multiwell cartridge with integrated array of amorphous silicon photosensors for chemiluminescence detection: Development, characterization and comparison with cooled-CCD luminograph. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 5645–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novo, P.; Moulas, G.; Prazeres, D.M.F.; Chu, V.; Conde, J.P. Detection of ochratoxin A in wine and beer by chemiluminescence-based ELISA in microfluidics with integrated photodiodes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 176, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.R.G.; Ramadas, D.; Chu, V.; Aires-Barros, M.R.; Conde, J.P.; Viana, A.S.; Cascalheira, A.C. An ultrarapid and regenerable microfluidic immunoassay coupled with integrated photosensors for point-of-use detection of ochratoxin A. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 235, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.R.; Santos, D.R.; Chu, V.; Azevedo, A.M.; Aires-Barros, M.R.; Conde, J.P. A point-of-use microfluidic device with integrated photodetector array for immunoassay multiplexing: Detection of a panel of mycotoxins in multiple samples. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, F.; Sberna, C.; Petrucci, G.; Reverberi, M.; Domenici, F.; Fanelli, C.; Manetti, C.; de Cesare, G.; DeRosa, M.; Nascetti, A.; Caputo, D. Aptamer-based sandwich assay for on chip detection of Ochratoxin A by an array of amorphous silicon photosensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 230, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, P.-C.; Locascio, L.E.; Lee, C.S. Integrated plastic microfluidic devices with ESI-MS for drug screening and residue analysis. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 2048–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kussak, A.; Nilsson, C.A.; Andersson, B.; Langridge, J. Determination of aflatoxins in dust and urine by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1995, 9, 1234–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Lin, S.-L.; Chan, S.-A.; Lin, T.-Y.; Fuh, M.-R. Microfluidic chip-based nano-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry for quantification of aflatoxins in peanut products. Talanta 2013, 113, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Lin, Z. Recent developments and applications of surface plasmon resonance biosensors for the detection of mycotoxins in foodstuffs. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnik, V.; Anderluh, G. Toxin detection by surface plasmon resonance. Sensors 2009, 9, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edupuganti, S.R.; Edupuganti, O.P.; O’Kennedy, R. Biological and synthetic binders for immunoassay and sensor-based detection: Generation and characterisation of an anti-AFB2 single-chain variable fragment (scFv). World Mycotoxin J. 2013, 6, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edupuganti, S.R.; Edupuganti, O.P.; O’Kennedy, R. Generation of anti-zearalenone scFv and its incorporation into surface plasmon resonance-based assay for the detection of zearalenone in sorghum. Food Control 2013, 34, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, T.; Takezawa, Y.; Hirano, S.; Tajima, O.; Maragos, C.M.; Nakajima, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kamata, Y.; Sugita-Konishi, Y. Rapid detection of nivalenol and deoxynivalenol in wheat using surface plasmon resonance immunoassay. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 673, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneely, J.P.; Sulyok, M.; Baumgartner, S.; Krska, R.; Elliott, C.T. A rapid optical immunoassay for the screening of T-2 and HT-2 toxin in cereals and maize-based baby food. Talanta 2010, 81, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneely, J.P.; Quinn, J.G.; Flood, E.M.; Hajšlová, J.; Elliott, C.T. Simultaneous screening for T-2/HT-2 and deoxynivalenol in cereals using a surface plasmon resonance immunoassay. World Mycotoxin J. 2012, 5, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennacchio, A.; Ruggiero, G.; Staiano, M.; Piccialli, G.; Oliviero, G.; Lewkowicz, A.; Synak, A.; Bojarski, P.; D’Auria, S. A surface plasmon resonance based biochip for the detection of patulin toxin. Opt. Mater. 2014, 36, 1670–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorokhin, D.; Haasnoot, W.; Franssen, M.C.R.; Zuilhof, H.; Nielen, M.W.F. Imaging surface plasmon resonance for multiplex microassay sensing of mycotoxins. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 400, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Annida, R.M.; Zuilhof, H.; van Beek, T.A.; Nielen, M.W.F. Analysis of mycotoxins in beer using a portable nanostructured imaging surface plasmon resonance biosensor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8263–8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Segarra-Fas, A.; Peters, J.; Zuilhof, H.; van Beek, T.A.; Nielen, M.W.F. Multiplex surface plasmon resonance biosensing and its transferability towards imaging nanoplasmonics for detection of mycotoxins in barley. Analyst 2016, 141, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Zuilhof, H.; van Beek, T.A.; Nielen, M.W.F. Biochip spray: Simplified coupling of surface plasmon resonance biosensing and mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; He, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.M. Sensitive detection of multiple mycotoxins by SPRi with gold nanoparticles as signal amplification tags. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 431, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karczmarczyk, A.; Reiner-Rozman, C.; Hageneder, S.; Dubiak-Szepietowska, M.; Dostálek, J.; Feller, K.-H. Fast and sensitive detection of ochratoxin A in red wine by nanoparticle-enhanced SPR. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 937, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karczmarczyk, A.; Dubiak-Szepietowska, M.; Vorobii, M.; Rodriguez-Emmenegger, C.; Dostálek, J.; Feller, K.-H. Sensitive and rapid detection of aflatoxin M1 in milk utilizing enhanced SPR and p(HEMA) brushes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 81, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, Y.-P.; Kim, I.-H.; Ko, S. Rapid detection of aflatoxin B 1 by a bifunctional protein crosslinker-based surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Food Control 2014, 36, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Feng, M.; Zuo, L.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Shan, G.; Luo, S.-Z. An aptamer based surface plasmon resonance biosensor for the detection of ochratoxin A in wine and peanut oil. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 65, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Q. Aptamer based surface plasmon resonance sensor for aflatoxin B1. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 2605–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Byun, J.-Y.; Mun, H.; Shim, W.-B.; Shin, Y.-B.; Li, T.; Kim, M.-G. A regeneratable, label-free, localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) aptasensor for the detection of ochratoxin A. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 59, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, M.; Sonato, A.; De Girolamo, A.; Pascale, M.; Romanato, F.; Rinaldi, R.; Arima, V. An aptamer-based SPR-polarization platform for high sensitive OTA detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 241, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-W.; Chang, H.-J.; Lee, N.; Chun, H.S. A surface plasmon resonance sensor for the detection of deoxynivalenol using a molecularly imprinted polymer. Sensors 2011, 11, 8654–8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-W.; Chang, H.-J.; Lee, N.; Kim, J.-H.; Chun, H.S. Detection of mycoestrogen zearalenone by a molecularly imprinted polypyrrole-based surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atar, N.; Eren, T.; Yola, M.L. A molecular imprinted SPR biosensor for sensitive determination of citrinin in red yeast rice. Food Chem. 2015, 184, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.; Bhaskar, A.S.B.; Tripathi, B.K.; Pandey, P.; Boopathi, M.; Rao, P.V.L.; Singh, B.; Vijayaraghavan, R. Supersensitive detection of T-2 toxin by the in situ synthesized π-conjugated molecularly imprinted nanopatterns. An in situ investigation by surface plasmon resonance combined with electrochemistry. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 2534–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, B.; Chen, L. SERS Tags: Novel optical nanoprobes for bioanalysis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1391–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galarreta, B.C.; Tabatabaei, M.; Guieu, V.; Peyrin, E.; Lagugné-Labarthet, F. Microfluidic channel with embedded SERS 2D platform for the aptamer detection of ochratoxin A. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Lu, Z.; Tan, X.; Xiao, X.; Wang, P.; Wu, L.; Shao, K.; Yin, W.; Han, H. Ultrasensitive detection of aflatoxin B1 by SERS aptasensor based on exonuclease-assisted recycling amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 97, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majer-Baranyi, K.; Székács, A.; Szendrő, I.; Kiss, A.; Adányi, N. Optical waveguide lightmode spectroscopy technique–based immunosensor development for deoxynivalenol determination in wheat samples. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 233, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer-Baranyi, K.; Zalán, Z.; Mörtl, M.; Juracsek, J.; Szendrő, I.; Székács, A.; Adányi, N. Optical waveguide lightmode spectroscopy technique-based immunosensor development for aflatoxin B1 determination in spice paprika samples. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adányi, N.; Levkovets, I.A.; Rodriguez-Gil, S.; Ronald, A.; Váradi, M.; Szendrő, I. Development of immunosensor based on OWLS technique for determining Aflatoxin B1 and Ochratoxin A. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2007, 22, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagkali, V.; Petrou, P.S.; Salapatas, A.; Makarona, E.; Peters, J.; Haasnoot, W.; Jobst, G.; Economou, A.; Misiakos, K.; Raptis, I. Detection of ochratoxin A in beer samples with a label-free monolithically integrated optoelectronic biosensor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 323, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, A.C.; Osterfeld, S.J.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.X.; Davis, R.W.; Jejelowo, O.A.; Pourmand, N. Sensitive giant magnetoresistive-based immunoassay for multiplex mycotoxin detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 25, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mycotoxins | Abbreviation | Toxicities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFs | Aflatoxin B1 | AFB1 | AFs play an important role in developing countries; they have acute toxicity and can lead to cancer, immunologic suppression, and nutritional interference [25,26,27]. AFB1 is the most potent carcinogenic agent [28]. AFB1 and AFM1 are classified as group 1 carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [29,30]. |

| Aflatoxin B2 | AFB2 | ||

| Aflatoxin M1 | AFM1 | ||

| Aflatoxin G1 | AFG1 | ||

| Aflatoxin G2 | AFG2 | ||

| Alternaria toxins | Alternariol | AOH | AOH and AME have no acute toxic effects, but possess carcinogenicity, with an especially high incidence of esophageal cancer [31]. Moreover, they also display mutagenicity, genotoxicity, and cytotoxicity, and can induce DNA breaks and inhibit the activity of topoisomerase [32,33,34]. |

| Altenariol monomethyl ether | AME | ||

| Tenuazonic acid | TeA | TeA has acute toxicity and was listed in the Food and Drug Administration (FAD) toxic chemical register [32,35]; it inhibits protein synthesis [36] and has cytotoxic [37], carcinogenic, and synergistic effects [38]. | |

| Ochratoxin A | OTA | OTA has nephrotoxic, hepatotoxic, neurotoxic, teratogenic, and immunotoxic effects [39,40], and is classified as a Group 2B carcinogen [41]. | |

| Deoxynivalenol | DON | DON displays cytotoxicity [42,43] and can induce emesis, anorexia and diarrhea, weight loss, neuroendocrine changes, immunological effects, leukocytosis, hemorrhaging, or circulatory shock [44]. | |

| Zearalenone | ZEA | ZEA displays carcinogenicity, immunotoxicity, genotoxicity, reproductive and developmental toxicity; in addition, it has an effect on the endocrine system [16,45,46]. | |

| Patulin | PTL | PTL displays neurotoxicity, embryotoxicity, teratogenicity, immunotoxicity, and can cause convulsions, dyspnea, pulmonary congestion, edema, ulceration, hyperemia, and distension of the gastrointestinal tract [47,48]. | |

| T-2 toxin | T-2 | T-2 is a potent inhibitor of protein synthesis and mitochondrial function, and shows immunosuppressive and cytotoxic effects [49]; it also has extremely toxic effects on the skin and mucous surfaces [50,51]. | |

| Fumonisin B1 | FB1 | FB1 can lead to hepatotoxicity, cancer, and apoptosis [52,53], and can cause pulmonary edema and hydrothorax in pigs [54]. FB1 is classified as a Group 2B carcinogen [41]. | |

| Citrinin | CIT | CIT displays reproductive toxicity, as well as nephrotoxic, embryotoxic, teratogenic, hepatotoxic, immunotoxic, and carcinogenic properties [55,56,57]. | |

| Materials | Process | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic materials | Silicon [68] | Standard photolithography | Resistance to organic solvents, high thermoconductivity, simple metal deposition, stable electroosmotic mobility. | Fragile, opaque, poor electrical insulation, hardness, high cost, time-consuming, labor-intensive, the bonding is difficult and requires a sterile environment. |

| Glass [69] | Standard photolithography | Optically transparent and electrically insulating, resistance to organic solvents, high thermoconductivity, simple metal deposition, stable electroosmotic mobility, easy surface modification. | Fragile, high cost, time-consuming, labor-intensive, bonding is difficult and requires a sterile environment. | |

| Elastomeric polymers | PDMS [70] | Cast molding | Optically transparent, high elasticity, low cost, easy and reversible binding, non-toxicity, permeability, compatible for cell culture, could integrate with the micropump and microvalve. | Could not withstand high temperatures, low thermoconductivity, strong nonspecific adsorption, poor organic solvent compatibility. |

| Rigid plastic polymers | PMMA [71] | Thermal molding | Organic solvent compatibility better than PDMS, low cost, can produce thousands of replicas at a high rate, the thermal bonding does not require a sterile environment. | Poor permeability and heat conductivity, high rigidity, difficult surface modification, cannot withstand high temperatures. |

| PI [72] | ||||

| PC [73] | ||||

| PS [74] | ||||

| PET [75] | ||||

| PVC [76] | ||||

| COC [77] | ||||

| Teflon PFA [78] | Extremely inert to chemical solvents, optically transparent, moderate permeability, antifouling, proper mechanical strength, low nonspecific absorption, no leaching of residue molecules from the material bulk into the solution in the channel. | Melting temperatures are high (over 280 °C). | ||

| Teflon FEP [78] | ||||

| Hydrogel polymers | PEG [79,80] | UV-induced polymerization | Highly porous with controllable pore sizes, allowing small molecules or even bio-nanoparticles to diffuse through, compatible for cell culture, short preparation time. | The bonding is difficult. |

| Photosensitive polymer | SU-8 photoresist [81] | Photolithography | Stable even at high temperatures, resistant to most solvents, and optically transparent. | High cost, high stiffness, poor permeability, and non-uniform thickness. |

| NOA81 [82] | Transparent, rapid, solvent-resistant, lower auto-fluorescence, and the thickness can be easily manipulated. | |||

| pCLLA [83] | Non-toxicity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, rapidness, and flexibility in materials processing. | |||

| Paper | Paper [84] | Lithographic methods and printing (cutting) methods | Portable and low-cost analysis, without the need for power or external components; large surface-to-volume ratio, the cheapest materials. | Liquids may not be well confined in the channel due to hydrophobicity, the applicable detection methods are relatively limited, low detection sensitivity, evaporation of liquid. |

| Target Analyte | Detection Method | Characteristic of the Microchip | Real Sample | LOD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTA | Fluorescence detection | PDMS microfluidic chip based on aqueous two-phase extraction | Red wine | 0.26 μg/L | [22] |

| AFB1 | Fluorescence detection | Smectite-PAM nanocomposite based on strip microfluidic sensor chip | Corn | 6.09 μg/kg | [86] |

| FB1 | Fluorescence detection | Microarray immunochip based on synthetic mimotopes | Maize and wheat | 11.1 μg/L | [89] |

| OTA | Fluorescence detection | Microarray immunochip | Cereals | 3.8–100 μg/kg | [90] |

| Coffee | 7 μg/kg | ||||

| Wine | 38 μg/kg | ||||

| DON | Fluorescence detection | Microarray immunochip | Oats | 0.2–50 μg/kg | [91] |

| Effluent | 4 μg/L | ||||

| AFB1 | Fluorescence detection | Protein microarray immunochip | Drinking water | 0.01 μg/L | [92] |

| AFM1 | 0.24 μg/L | ||||

| DON | 15.45 μg/L | ||||

| OTA | 15.39 μg/L | ||||

| T-2 | 0.05 μg/L | ||||

| ZEA | 0.01 μg/L | ||||

| AFB1 | Fluorescence detection | High throughput biochip based on photonic crystal microsphere (PHCM) suspension array | Cereal samples | 15.96 × 10−6 μg/L | [93] |

| OTA | 3.96 × 10−6 μg/L | ||||

| FB1 | 0.011 μg/L | ||||

| OTA | Chemiluminescence detection | Indirect competitive immunochip | Green coffee | 0.3 μg/L | [96] |

| AFs, OTA, DON, FB1 | Chemiluminescence detection | Regenerable microarray immunochip | Oat extracts | / | [97] |

| OTA | Colorimetric detection | Combination of an OTA-responsive hydrogel with a distance-based readout V-chip | Beer | 0.51 μg/L | [98] |

| AFB1 | Colorimetric detection | Combination of an AFB1-responsive hydrogel with a distance-based readout V-chip | Beer | 0.55 μg/L | [99] |

| AFB1 | Colorimetric detection | Integrated, smartphone-app-chip (SPAC) system | Corn | 3 μg/kg | [100] |

| AFB1 | Electrochemical detection | 96-well screen-printed microarray immunochip | Corn | 0.03 μg/L | [103] |

| AFM1 | Electrochemical detection | Gold microelectrode array immunochip | Milk | 0.008 μg /L | [104] |

| CIT | Electrochemical detection | Microfluidic electrochemical immunochip | Rice | 0.1 μg/L | [105] |

| DON | Electrochemical detection | Microfluidic chip coupled with gold microelectrode arrays | Wheat | 6.25 μg/L | [106] |

| AF | Electrochemical detection | Microfluidic chip coupled with gold microelectrode arrays | Foods | 0.08–0.65 μg/kg | [107] |

| ZEA | Electrochemical detection | Microfluidic chips coupled with magnetic bead-based immunoassay | Baby foods | 1 μg/kg | [108] |

| ZEA | Electrochemical detection | Microfluidic chips coupled with magnetic bead-based immunoassay | Infant foods | 0.4 μg/L | [109] |

| ZEA | Electrochemical detection | Microfluidic chips coupled with magnetic bead-based ELISA | Feedstuffs | 0.41 μg/L | [110] |

| OTA | Electrochemical detection | Microfluidic chips coupled with magnetic bead-based ELISA | Apples | 50 μg/kg | [111] |

| OTA | Photo-electrochemical detection | Chemiluminescence-based ELISA in microfluidic chip with integrated photodiodes | Beer | 0.1 μg/L | [115] |

| Red wine | 2 μg/L | ||||

| OTA | Photo-electrochemical detection | Regenerable chemiluminescence-based immunoassay in microfluidic chip with integrated photodiodes | Red wine | <2 μg/L | [116] |

| OTA, AFB1 and DON | Photo-electrochemical detection | Microfluidic multiplexed biosensor chip with a permanent magnet valves | / | / | [117] |

| OTA | Photo-electrochemical detection | Aptamer-based sandwich assay in a multichannel microfluidic chip | Beer | 0.82 μg/L | [118] |

| AFB1 | MS | Plastic microfluidic chip coupled with ESI-MS | / | / | [119] |

| AFs | MS | Microfluidic chip-based nano LC coupled with QqQ-MS | Peanut | 0.004–0.008 μg/kg | [121] |

| AFB2 | SPR | Microchip SPR immunochip using anti-AFB2 scFv antibody | Almond | 0.9 μg/L | [124] |

| ZEA | SPR | Microchip SPR immunochip using anti-ZEA scFv antibody | Sorghum | 7.8 μg/L | [125] |

| NIV | SPR | Microchip SPR immunochip using monoclonal antibody | Wheat | 200 μg/kg | [126] |

| DON | 100 μg/kg | ||||

| T-2 and HT-2 | SPR | Microchip SPR immunochip using monoclonal antibody | Baby food and breakfast cereal | 25 μg/kg | [127] |

| Wheat | 26 μg/kg | ||||

| T-2 HT-2 | SPR | Microchip SPR immunochip using monoclonal antibody | Wheat | 31 μg/kg | [128] |

| Breakfast cereal | 47 μg/kg | ||||

| Maize-based baby food | 36 μg/kg | ||||

| DON | Wheat | 12 μg/kg | |||

| Breakfast cereal | 1 μg/kg | ||||

| Maize-based baby food | 29 μg/kg | ||||

| PTL | SPR | Microchip SPR immunochip using polyclonal mono-specific antibodies | / | 15.41 μg/L | [129] |

| DON | iSPR | Microchip multiplex microassay iSPR immunochip | Maize | 84 μg/kg | [130] |

| Wheat | 68 μg/kg | ||||

| ZEA | Maize | 64 μg/kg | |||

| Wheat | 40 μg/kg | ||||

| DON | iSPR | Microchip nanostructured iSPR immunochip | Beer | 17 μg/L | [131] |

| OTA | 7 μg/L | ||||

| DON | iSPR | Microchip benchtop SPR (Biacore) with two separates nanostructured iSPR immunochip | Barley | 26 μg/kg | [132] |

| ZEA | 6 μg/kg | ||||

| T-2 | 0.6 μg/kg | ||||

| OTA | 3 μg/kg | ||||

| FB1 | 2 μg/kg | ||||

| AFB1 | 0.6 μg/kg | ||||

| DON | SPR-MS | Coupled SPR immunochip and ambient ionization MS | Beer | / | [133] |

| AFB1 | iSPR | AuNP-enhanced iSPR immunochip | Spiked peanut | 0.008 μg/L | [134] |

| OTA | 0.03 μg/L | ||||

| AEN | 0.015 μg/L | ||||

| OTA | SPR | AuNP-enhanced SPR immunochip | Red wine | 0.068 μg/L | [135] |

| AFM1 | SPR | AuNP-enhanced SPR immunochip | Milk | 0.018 μg/L | [136] |

| AFB1 | SPR | SPR immunochip based on GBP-ProG crosslinker | Buffer and corn extracts | 1000 μg/L | [137] |

| OTA | SPR | SPR microchip based on aptamer | Wine and peanut oil | 0.005 μg/L | [138] |

| AFB1 | SPR | SPR microchip based on aptamer | Red wine | 124.91 μg/L | [139] |

| OTA | SPR | Localized SPR microchip based on aptamer | Ground corn samples | 403 μg/L | [140] |

| OTA | SRP | SPR-polarization microchip based on aptamer | / | 0.005 μg/L | [141] |

| DON | SPR | SPR microchip based on MIP | DON standard solution | >1 μg/L | [142] |

| ZEA | SPR | SPR microchip based on MIP | Corn | 0.3 μg/kg | [143] |

| CIT | SPR | SPR biosensor chip based on MIP | Red yeast rice | 0.0017 μg/L | [144] |

| T-2 | SPR | SPR microchip based on nanopatterned π-conjugated MIP | / | 0.47 × 10-4 μg/L | [145] |

| OTA | SERS | Microfluidic chip embedded 2D SERS platform | / | / | [147] |

| AFB1 | SERS | SERS aptasensor chip based on exonuclease-assisted recycling amplification | Spiked peanuts | 0.4 × 10−6 μg/L | [148] |

| DON | OWLS | Immunochip based on OWLS | Wheat flour | / | [149] |

| AFB1 | OWLS | Immunochip based on OWLS | Spice paprika samples | 0.35 μg/kg | [150] |

| AFB1, OTA | OWLS | Immunochip based on OWLS | Barley and wheat flour samples | / | [151] |

| OTA | BB-MZI | Si immunochip based on monolithically integrated BB-MZI | Beer | 2.0 μg/L | [152] |

| AFB1, ZEA, HT-2 | GMR | Multiplex magnetic nanotag-based biochip | / | 0.05 μg/L | [153] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Man, Y.; Liang, G.; Li, A.; Pan, L. Recent Advances in Mycotoxin Determination for Food Monitoring via Microchip. Toxins 2017, 9, 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9100324

Man Y, Liang G, Li A, Pan L. Recent Advances in Mycotoxin Determination for Food Monitoring via Microchip. Toxins. 2017; 9(10):324. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9100324

Chicago/Turabian StyleMan, Yan, Gang Liang, An Li, and Ligang Pan. 2017. "Recent Advances in Mycotoxin Determination for Food Monitoring via Microchip" Toxins 9, no. 10: 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9100324

APA StyleMan, Y., Liang, G., Li, A., & Pan, L. (2017). Recent Advances in Mycotoxin Determination for Food Monitoring via Microchip. Toxins, 9(10), 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9100324