Spatial Rearrangement and Mobility Heterogeneity of an Anionic Lipid Monolayer Induced by the Anchoring of Cationic Semiflexible Polymer Chains

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Model and Simulation Method

2.1. Monte Carlo Model

2.2. Simulation Details

3. Results and Discussion

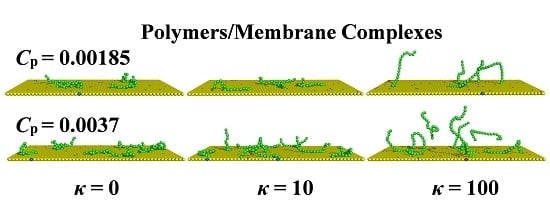

3.1. Sequestration of Anionic Lipids Underneath Anchored Polymers

3.2. Distribution of the Anchored Polymer Segments

3.3. Restricted Mobility of the Polymer/Lipids Complexes

3.4. Mobility Gradient in Lipid Clusters

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | Phosphatidyl-choline |

| PS | Phosphatidylserine |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| MSD | Mean-square-displacement |

| RDF | Radial distribution function |

| BAC | Bond angle correlation function |

| Lp | Persistence length |

| lB | Bjerrum length |

| lD− | Debye screening length |

| κ | Parameter to tailor the degree of polymer chain rigidity |

| Cp | Polymer concentration |

| φs | Fraction of the sequestered lipids in the interaction zones of all anchored polymers |

| Ms | Number of the sequestered lipids in the zones underneath each anchored polymer |

| gPIP2(r) | Radial distribution function for PIP2–PIP2 lipids |

| gPS(r) | Radial distribution function for PS–PS lipids |

| gs(r) | Distribution of the segments of the anchored polymers above the monolayer surface |

| mpc | MSD of the center of mass of the anchored polymers |

| mpd | MSD of lipid micro-domain |

| mpl | MSD of single sequestered lipids |

References

- McLaughlin, S.; Murray, D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature 2005, 438, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance, J.E.; Steenbergen, R. Metabolism and functions of phosphatidylserine. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005, 44, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, S.; Wang, J.Y.; Gambhir, A.; Murray, D. PIP2 AND proteins: Interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. 2002, 31, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Paolo, G.; De Camilli, P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature 2006, 443, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, W.D.; Inoue, T.; Park, W.S.; Kim, M.L.; Park, B.O.; Wandless, T.J.; Meyer, T. PI(3,4,5)P-3 and PI(4,5)P-2 lipids target proteins with polybasic clusters to the plasma membrane. Science 2006, 314, 1458–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, T.; Gilbert, G.E.; Shi, J.; Silvius, J.; Kapus, A.; Grinstein, S. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science 2008, 319, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.J.; Li, X.S.; Kaliszewski, M.J.; Zhuang, X.D.; Smith, A.W. Tuning the mobility coupling of quaternized polyvinylpyridine and anionic phospholipids in supported lipid bilayers. Langmuir 2015, 31, 1784–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambhir, A.; Hangyas-Mihalyne, G.; Zaitseva, I.; Cafiso, D.S.; Wang, J.Y.; Murray, D.; Pentyala, S.N.; Smith, S.O.; McLaughlin, S. Electrostatic sequestration of PIP2 on phospholipid membranes by basic/aromatic regions of proteins. Biophys. J. 2004, 86, 2188–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiewska, U.; Gambhir, A.; Hangyas-Mihalyne, G.; Zaitseva, I.; Radler, J.; McLaughlin, S. Membrane-bound basic peptides sequester multivalent (PIP2), but not monovalent (PS), acidic lipids. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.J.; Kohram, M.; Zhuang, X.D.; Smith, A.W. Interactions and translational dynamics of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2) lipids in asymmetric lipid bilayers. Langmuir 2016, 32, 1732–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.M.; Lietha, D.; Ceccarelli, D.F.; Karginov, A.V.; Rajfur, Z.; Jacobson, K.; Hahn, K.M.; Eck, M.J.; Schaller, M.D. Spatial and temporal regulation of focal adhesion kinase activity in living cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, J.; Annepu, H.; Sharma, A. Contact instability of a soft elastic film bonded to a patterned substrate. J. Adhesion 2011, 87, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.D.; Villalobos, C.; Andrade, R. TRPC channels mediate a muscarinic receptor-induced afterdepolarization in cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 10038–10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, L.H.; Xue, S.; Joo, S.W.; Qian, S.; Hsu, J.P. Field effect control of surface charge property and electroosmotic flow in nanofluidics. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 4209–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollapour, M.; Phelan, J.P.; Millson, S.H.; Piper, P.W.; Cooke, F.T. Weak acid and alkali stress regulate phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 2006, 395, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, Y.J.; Perera, I.Y.; Brglez, I.; Davis, A.J.; Stevenson-Paulik, J.; Phillippy, B.Q.; Johannes, E.; Allen, N.S.; Boss, W.F. Increasing plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate biosynthesis increases phosphoinositide metabolism in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1603–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mclaughlin, S. The electrostatic properties of membranes. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1989, 18, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleva, E.; Ben-Tal, N.; Diamant, H. Increased concentration of polyvalent phospholipids in the adsorption domain of a charged protein. Biophys. J. 2004, 86, 2165–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbamala, E.C.; Ben-Shaul, A.; May, S. Domain formation induced by the adsorption of charged proteins on mixed lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 2005, 88, 1702–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, R.S.; Pais, A.; Linse, P.; Miguel, M.G.; Lindman, B. Polyion adsorption onto catanionic surfaces. A Monte Carlo study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 11781–11788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loew, S.; Hinderliter, A.; May, S. Stability of protein-decorated mixed lipid membranes: The interplay of lipid-lipid, lipid-protein, and protein-protein interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 045102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzlil, S.; Ben-Shaul, A. Flexible charged macromolecules on mixed fluid lipid membranes: Theory and Monte Carlo simulations. Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 2972–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khelashvili, G.; Weinstein, H.; Harries, D. Protein diffusion on charged membranes: A dynamic mean-field model describes time evolution and lipid reorganization. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 2580–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzlil, S.; Murray, D.; Ben-Shaul, A. The “Electrostatic-Switch” mechanism: Monte Carlo study of MARCKS-membrane interaction. Biophys. J. 2008, 95, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiselev, V.Y.; Marenduzzo, D.; Goryachev, A.B. Lateral dynamics of proteins with polybasic domain on anionic membranes: A dynamic Monte-Carlo study. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.D.; Ma, Y.Q. Theoretical and computational studies of dendrimers as delivery vectors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 705–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, C.K.; Chen, K.; Tian, W.D.; Ma, Y.Q. Computational investigations of a peptide-modified dendrimer interacting with lipid membranes. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013, 34, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.; Radhakrishnan, R. Coarse-Grained models for protein-cell membrane interactions. Polymers 2013, 5, 890–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.C.; Storm, D.R. Regulation of free calmodulin levels by neuromodulin—Neuron growth and regeneration. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990, 11, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.Q.; Shi, T.F.; An, L.J.; Huang, Q.R. Monte Carlo study of polyelectrolyte adsorption on mixed lipid membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.Z.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, R.; Shi, T.F.; An, L.J.; Huang, Q.R. Regulation of anionic lipids in binary membrane upon the adsorption of polyelectrolyte: A Monte Carlo simulation. AIP Adv. 2013, 3, 062128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.Q.; Yang, Y.B.; Shi, T.F.; An, L.J.; Huang, Q.R. Effect of polyelectrolyte adsorption on lateral distribution and dynamics of anionic lipids: A Monte Carlo study of a coarse-grain model. Eur. Biophys. J. 2014, 43, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.Z.; Ding, M.M.; Zhang, R.; Li, L.Y.; Shi, T.F.; An, L.J.; Huang, Q.R.; Xu, W.S. Effects of chain rigidity on the adsorption of a polyelectrolyte chain on mixed lipid monolayer: A Monte Carlo study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 6041–6049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.Z.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, R.; Shi, T.F.; An, L.J.; Huang, Q.R. Compositional redistribution and dynamic heterogeneity in mixed lipid membrane induced by polyelectrolyte adsorption: Effects of chain rigidity. Eur. Phys. J. E 2014, 37, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liang, H.J.; Wu, J.Z. Electrostatic origins of polyelectrolyte adsorption: Theory and Monte Carlo simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 044906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Duan, X.Z.; Shi, T.F.; Li, H.F.; An, L.J.; Huang, Q.R. Physical gelation of polypeptide-polyelectrolyte-polypeptide (ABA) copolymer in solution. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 6201–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K. Phase Transition and Critical Phenomena; Domb, C., Green, M.S., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, N.; Lookman, T.; Pink, D.A. On computer-simulation methods used to study models of 2-component lipid bilayers. Biochemistry 1984, 23, 3227–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metropolis, N.; Rosenbluth, A.W.; Rosenbluth, M.N.; Teller, A.H.; Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953, 21, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, S.; Chodanowski, P. Polyelectrolyte adsorption on an oppositely charged spherical particle. Chain rigidity effects. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 9556–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Muthukumar, M. Langevin dynamics simulation of counterion distribution around isolated flexible polyelectrolyte chains. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116, 9975–9982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akesson, T.; Woodward, C.; Jonsson, B. Electric double-layer forces in the presence of poly-electrolytes. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 91, 2461–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, B.; Radler, J.O. Conformation and self-diffusion of single DNA molecules confined to two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 1911–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lp [Å] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| κ | 0 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 100 |

| Ci = 0.03 M | 39.4 | 44.0 | 48.5 | 55.3 | 59.1 |

| Ci = 0.01 M | 47.4 | 49.5 | 51.2 | 56.8 | 60.7 |

| Ci = 0.001 M | 51.7 | 58.5 | 60.1 | 62.6 | 67.7 |

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Ding, M.; Shi, T.; An, L.; Huang, Q.; Xu, W.-S. Spatial Rearrangement and Mobility Heterogeneity of an Anionic Lipid Monolayer Induced by the Anchoring of Cationic Semiflexible Polymer Chains. Polymers 2016, 8, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym8060235

Duan X, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Ding M, Shi T, An L, Huang Q, Xu W-S. Spatial Rearrangement and Mobility Heterogeneity of an Anionic Lipid Monolayer Induced by the Anchoring of Cationic Semiflexible Polymer Chains. Polymers. 2016; 8(6):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym8060235

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Xiaozheng, Yang Zhang, Ran Zhang, Mingming Ding, Tongfei Shi, Lijia An, Qingrong Huang, and Wen-Sheng Xu. 2016. "Spatial Rearrangement and Mobility Heterogeneity of an Anionic Lipid Monolayer Induced by the Anchoring of Cationic Semiflexible Polymer Chains" Polymers 8, no. 6: 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym8060235