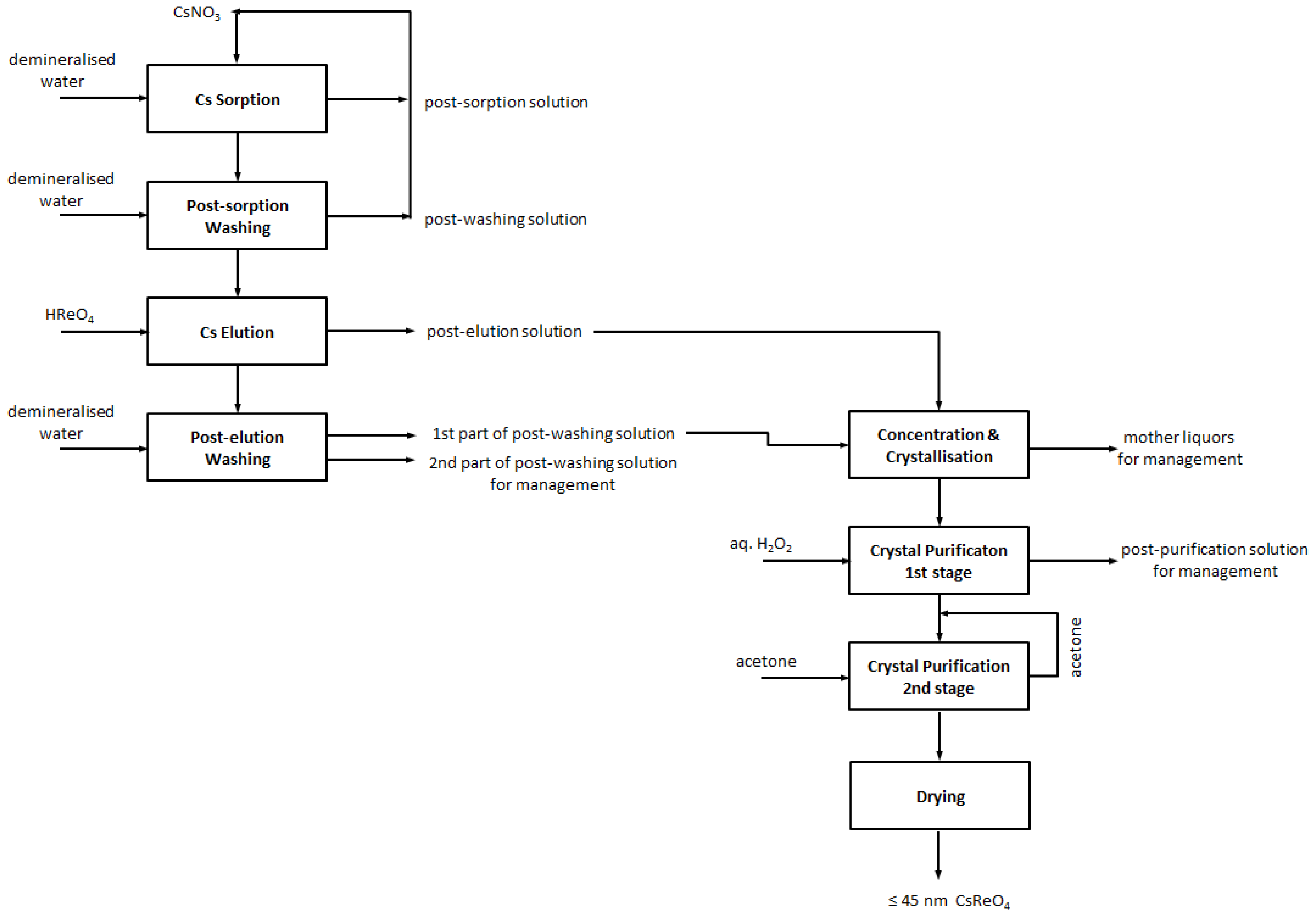

2.2. Cesium Perrhenate Preparation—Ion Exchange

A new method of anhydrous nanocrystalline cesium perrhenate synthesis, an alternative to the classical one, was developed. It is composed of two stages: sorption of Cs

+ ions and their elution by aqueous solution of perrhenic acid:

Tests were performed in static and dynamic conditions. Preliminary experiments at static conditions allowed the choice of the best-fitted cationite for Cs

+ sorption. Then, in further static tests, the effect of selected parameters (temperature, contact time of a solution with ion-exchange resin, and cesium concentration in an initial solution) on Cs

+ sorption efficiency of resins was determined. Ion-exchange selection was carried out using the following procedure: 10.0 g of ion-exchange resin was mixed for 30 min at ambient temperature with 100 cm

3 of cesium nitrate(V) aqueous solution containing 5.0 g/dm

3 Cs and followed by vacuum filtration. Solutions were analysed to estimate cesium content. Cesium sorption efficiency was calculated using the following formula:

where:

is the cesium mass in a solution before sorption (g);

is the cesium concentration in a solution after sorption (g/dm

3); and

is the volume of the solution after sorption (dm

3).

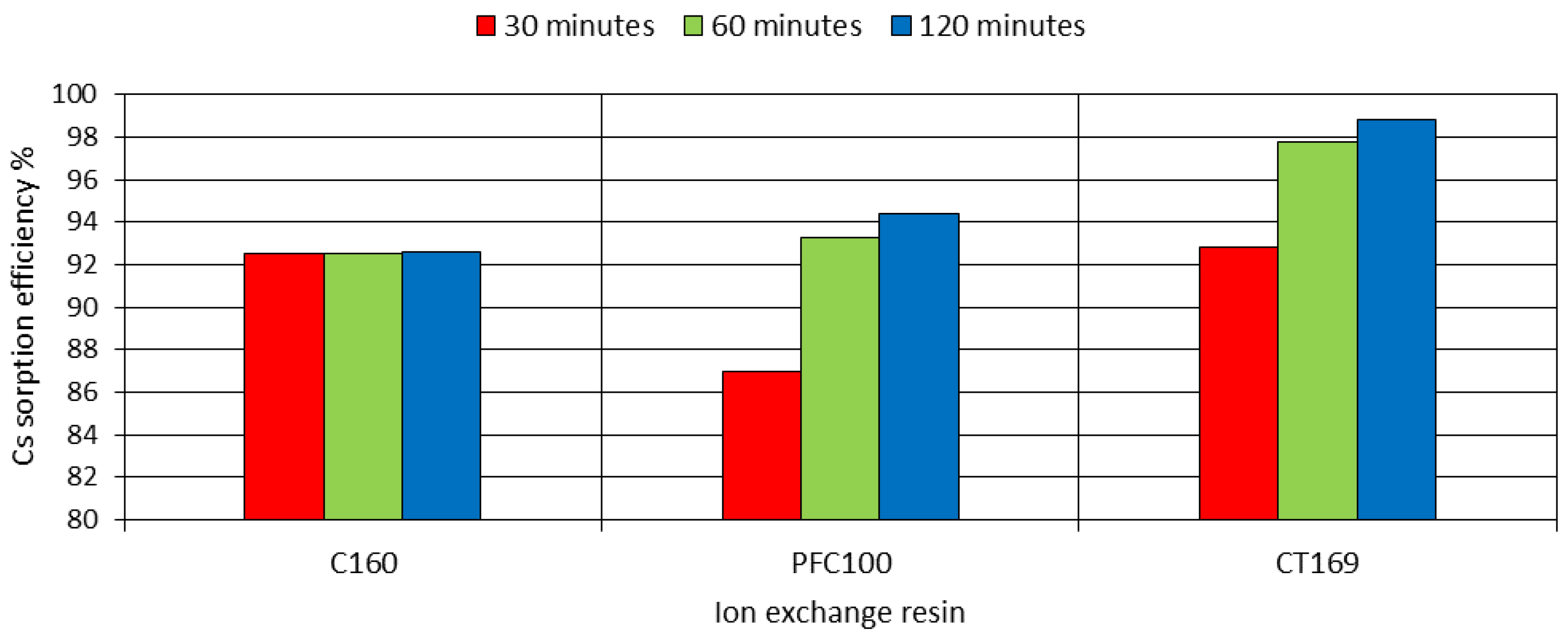

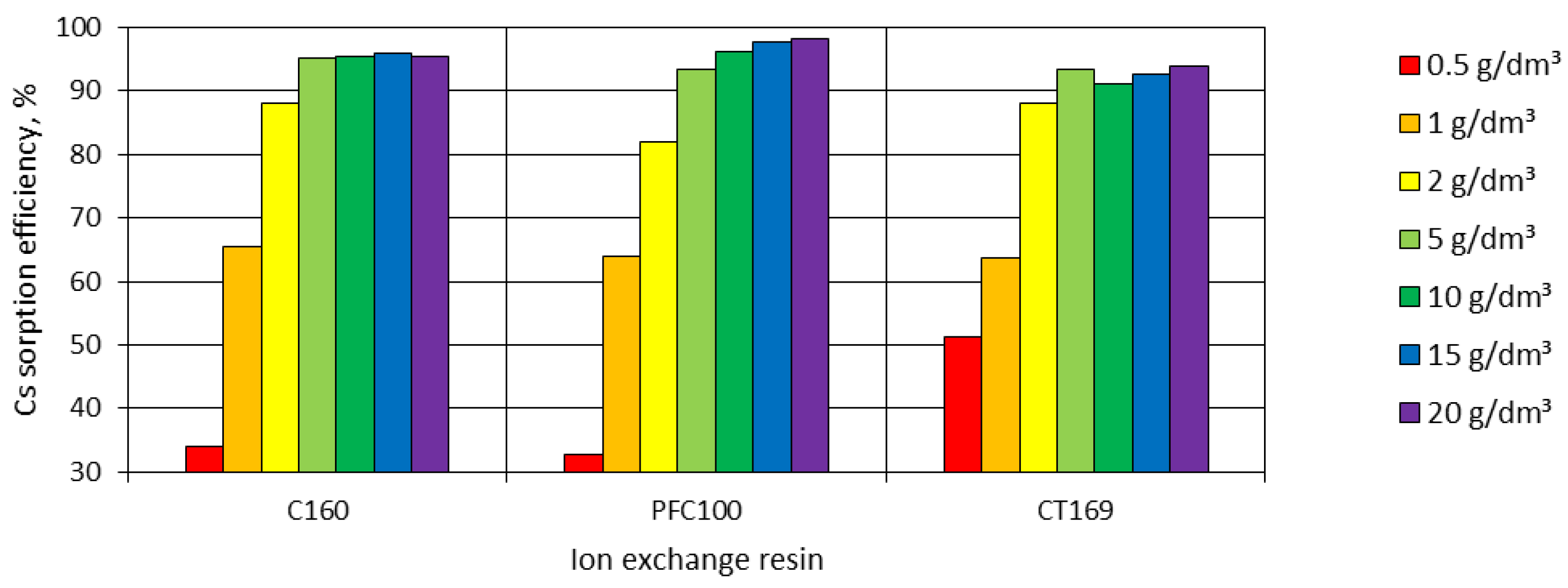

The effect of temperature, contact time, and cesium concentration of an initial solution on cesium sorption efficiency was conducted in the same conditions as presented for ion-exchange selection. The examined temperature was in the range 293–333 K, with a contact time of 30–120 min, and a cesium concentration of 0.5–20.0 g/dm3. The effect of contact time and cesium concentration on sorption efficiency was examined at ambient temperature, while the effect of cesium concentration was examined for a contact time of 60 min.

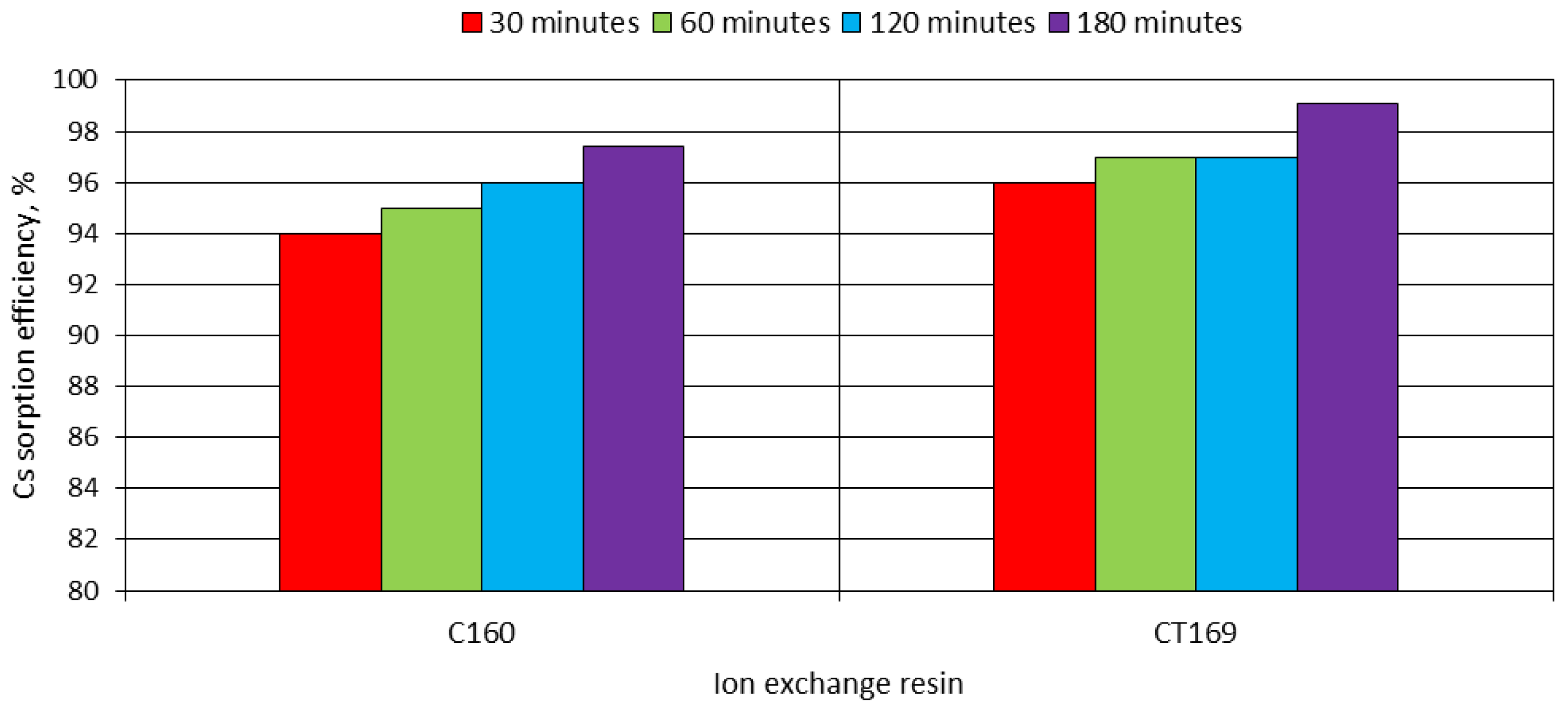

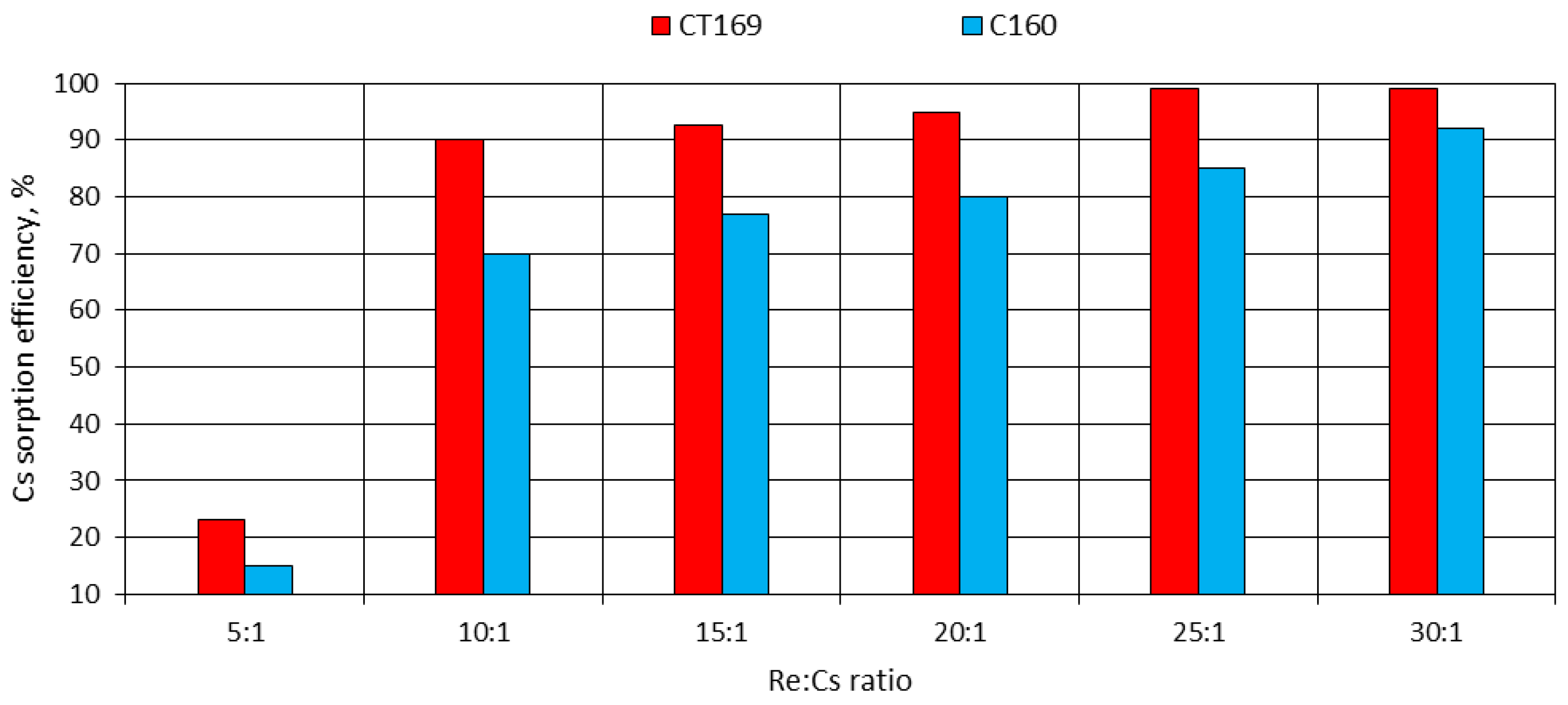

In the next stage, the influence of contact time, temperature, and rhenium–cesium ratio on Cs elution was determined. Ion-exchange resins after the sorption stage contained: C160: 4.6% Cs; PFC100: 4.5% Cs; CT169: 4.7% Cs. The procedure was as follows: 5.0 g of ion-exchange resin containing sorbed cesium was magnetically mixed with 10 cm

3 perrhenic acid of concentration 100.0 g/dm

3 Re. Solutions were mixed for 30 min, and vacuum filtered. Then, cesium content was analysed. The following parameter ranges were examined: contact time 30–180 min, temperature 293–333 K, and rhenium-to-cesium ratio 5:1–30:1. Contact time of 60 min was used to examine the effect of temperature and Re:Cs ratio. Elution efficiency was calculated using the formula:

where:

is the cesium mass in a solution before elution (g);

is the cesium concentration in a solution after elution (g/dm

3); and

′ is the volume of solution after elution (dm

3).

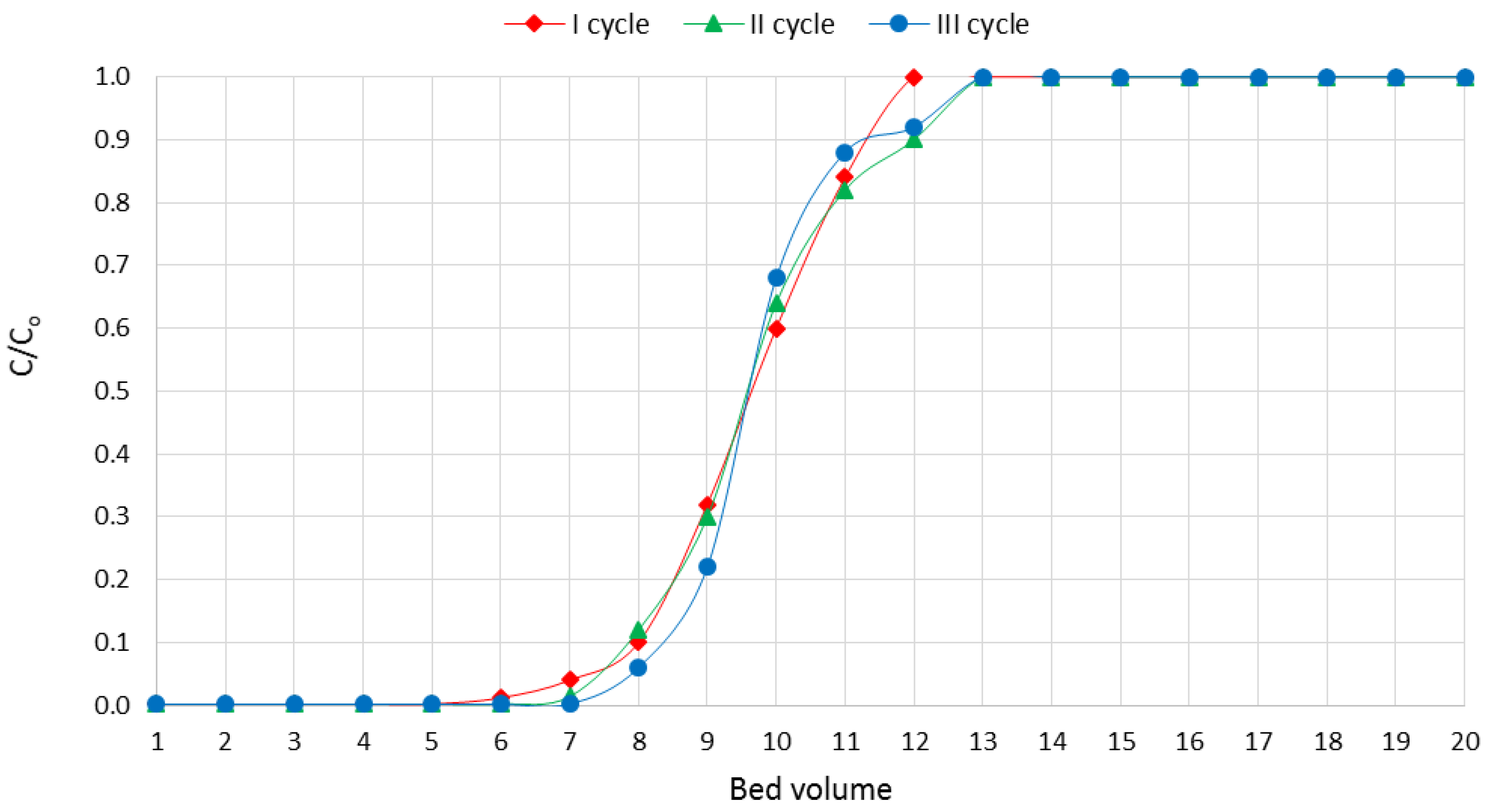

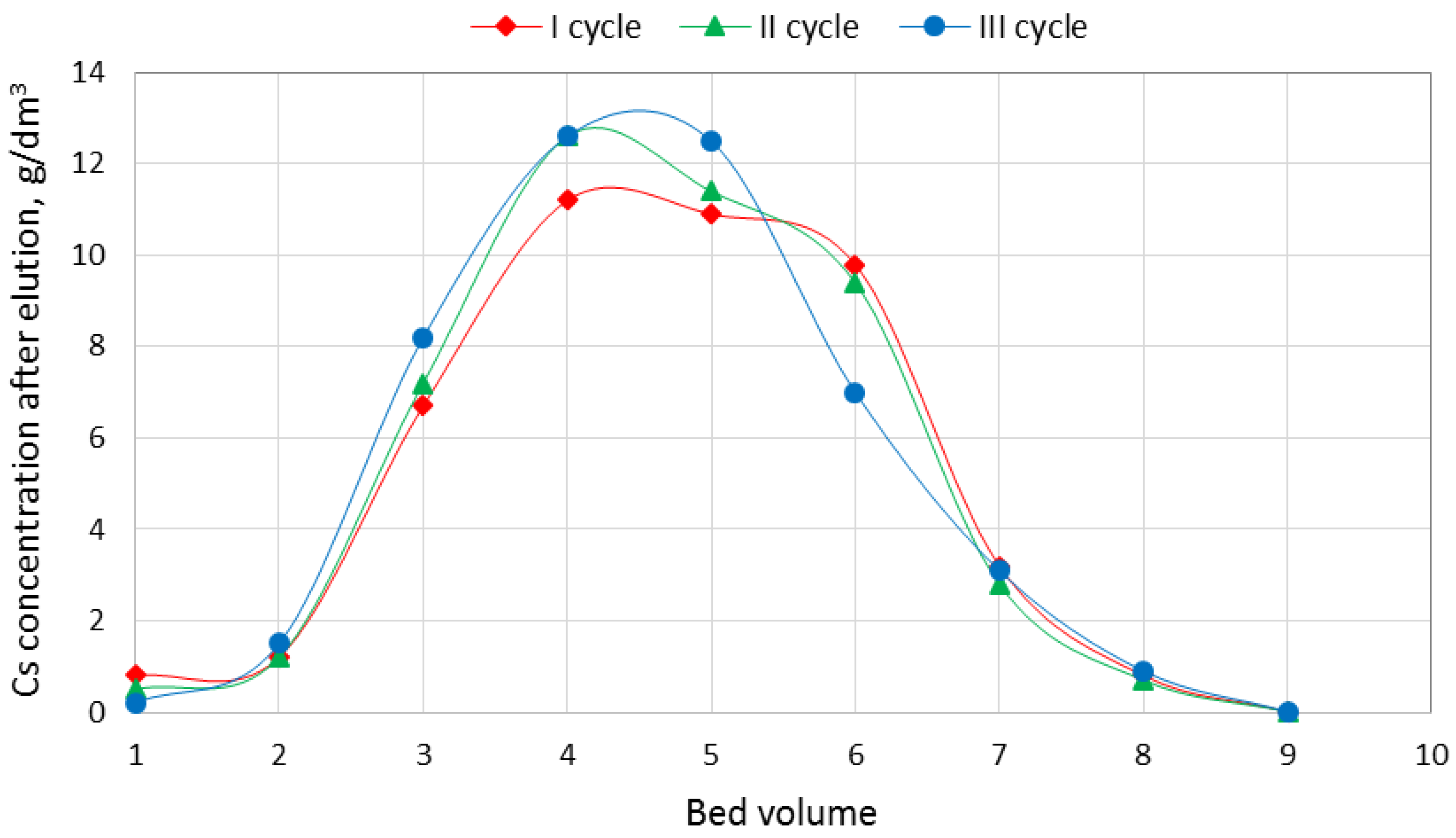

Dynamic tests were carried out according to the following procedure: 100 cm3 CT169 or C160 ion-exchange resins were placed in a column 2.5 cm in diameter. Then, a cesium nitrate(V) solution containing 5.0 g/dm3 Cs was added until the cesium concentration in the effluent reached the initial level. The effluent solution was separated into three portions of 100 cm3 and analysed for cesium content. After, the sorption ion-exchange resin was washed with distilled water until pH 7.0 was reached. Then, 600 cm3 perrhenic acid at a concentration of 100 g Re/dm3 was passed up the column. Ion-exchange resin was washed until neutral pH was reached and used in the next process.

Solutions from elution and the first portion of washing solutions (containing 1.0 g/dm

3 Cs) were concentrated. Three operation cycles were performed in this way. The succeeding data were evaluated: cesium ion sorption efficiency: Equation (1), cesium ion elution efficiency: Equation (2), ion-exchange saturation by cesium ions in each stage: Equation (3); OZ

1: bed volume for which cesium concentration is <0.01 g/dm

3; OZ

2: bed volume when the column is totally filled; OZ

3: bed volume when cesium concentration is higher than 5.0 g/dm

3, for elution; OZ

4: bed volume when cesium concentration is higher than 1.0 g/dm

3, for elution and washing after elution.

where:

is the cesium mass in a solution before sorption (g);

is the mass of ion-exchange resin (cm

3);

is the cesium concentration in solution after sorption (g/dm

3); and

is the volume of solution after sorption (dm

3).

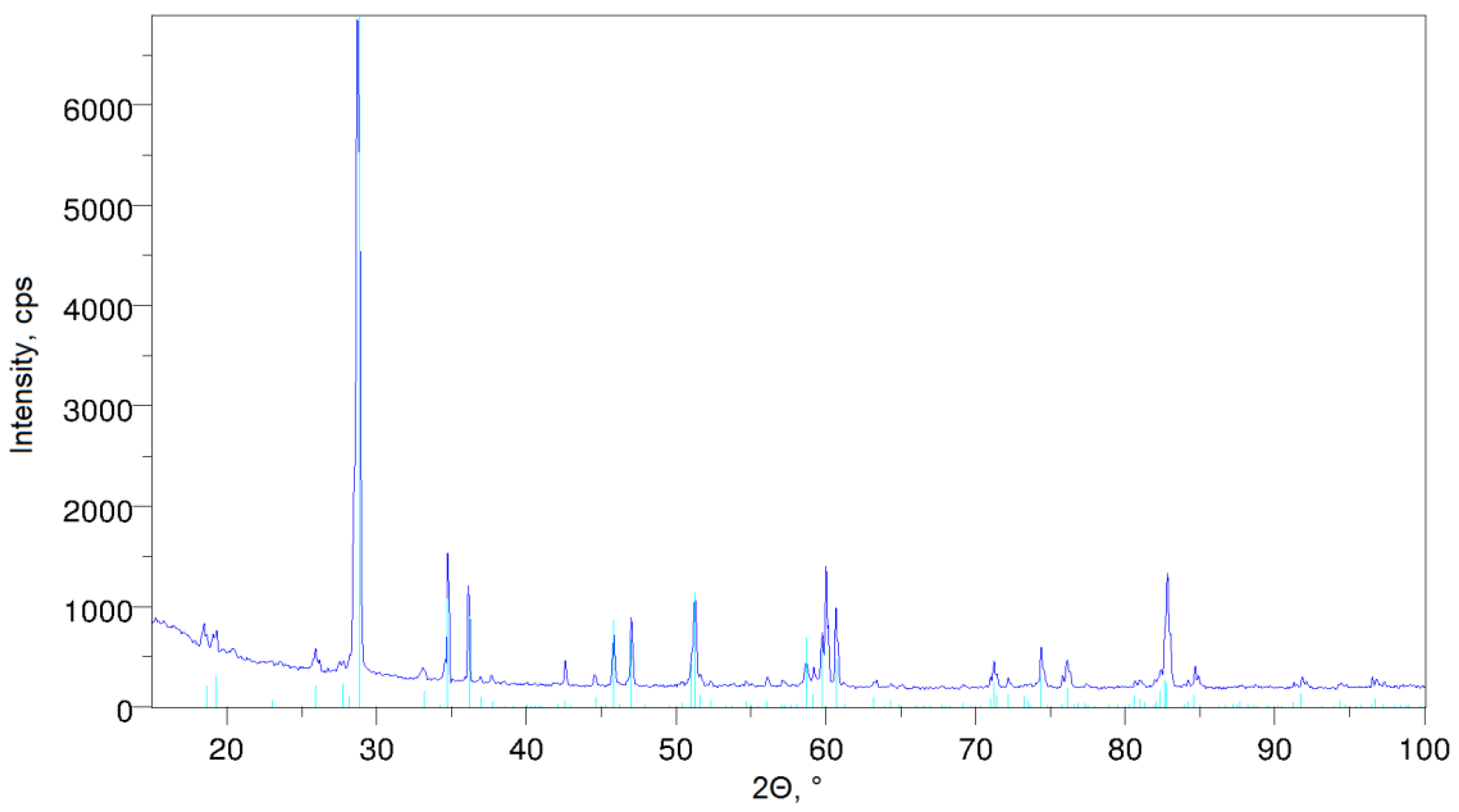

Solutions from elution and washing after elution were combined in such a way as to obtain different cesium concentrations, namely 3, 5, and 10 g/dm3 in a concentration stage. The volume of solutions directed to crystallisation was constant and equal to 1.5 dm3. Concentrated solutions were intensively mixed at temperatures up to 353 K. Then, solutions were cooled at 0.5 K/min until ambient temperature. Crystallised cesium perrhenate was separated from solutions by filtration. Additionally, cesium perrhenate prepared using 10 g/dm3 Cs solution was divided into five parts and directed to the purification stage. The purification process was a single- or two-step washing of filtered crystals. The washing media were 50 cm3 portions of 5% or 10% aqueous hydrogen peroxide solutions and/or 20 cm3 portions of anhydrous acetone. Purified crystals were dried at 393 K until constant mass. Cesium and rhenium content, as well as selected contaminations (i.e., As, Cu, Zn, Ca, Fe, Mo, Ni, Pb, Na, K, Mg, Bi) were analysed and the crystallite size was evaluated.