1. Introduction

Symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity typically co-occur with poor communication skills [

1,

2] and low levels of literacy [

3,

4,

5] in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The same comorbidities are also found in the general school population [

6,

7] and in other neurodevelopmental conditions including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [

8], specific language impairment (SLI) [

9], and dyslexia [

10,

11]. These overlapping symptom profiles may reflect dimensions of inattentive and hyperactive behaviour and cognitive difficulties that cut across traditional diagnostic categories [

12,

13,

14]. In the current study we adopt a dimensional approach to test the specificity of the associations between these dimensions of behaviour, communication and literacy skills in a large sample of children receiving support from specialist services for difficulties in attention, learning and/or memory. The sample included a small number of children with diagnosed developmental disorders and a substantial number with sub-clinical difficulties. The atypical and heterogeneous nature of the sample enabled us to investigate the extent to which impairments in language and behaviour co-occurred in children with problems related to educational progress.

Difficulties in both the formal learning of language structure and the use of language in different contexts are common in developmental disorders [

1,

15,

16,

17]. Structural aspects of language include the use of phonology, semantics, syntax and morphology. These skills are important for literacy development [

18,

19] and for expressing and understanding spoken language in communication [

20]. Pragmatic aspects of language involve the appropriate use of language in social communicative contexts such as maintaining appropriate topics, not talking excessively, turn-taking in conversations and interpreting non-verbal cues of others [

21,

22]. It is unclear whether impairments in pragmatic language arise as a secondary consequence of structural language problems [

23] or instead reflect social or behavioural difficulties [

7,

24]. Evidence that children can have pragmatic language difficulties in the absence of problems with language structure supports the view that these two dimensions of language impairment may have different sources [

22,

25].

Profiles of structural and pragmatic language difficulties differ across specific diagnostic groups. For example, pragmatic language impairments are common in high-functioning autism [

16] and ADHD [

1,

6,

21,

26], but structural language difficulties are more common in children with reading difficulties and SLI [

12,

14,

27]. However, there is also considerable heterogeneity within each diagnostic category, as demonstrated for example by the prevalence of pragmatic language difficulties among children with SLI [

28]. There is also substantial overlap between the linguistic profiles of children with different diagnoses, illustrated by the prevalence of pragmatic language difficulties in both children with ADHD and those with autism [

1]. These two groups also show elevated symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity typically common in both disorders [

29,

30,

31], illustrating how symptom profiles of language and behaviour problems may not be specific to particular disorders.

Pragmatic communication problems are also associated with the severity of symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity in other clinical and typically developing populations [

1,

6,

21]. A possible source of these co-morbid problems are the executive function difficulties frequently observed in children with attentional symptoms of ADHD [

32,

33]. It has been suggested that ADHD may arise from disruptions to two functionally distinct neurodevelopmental systems: cool cognitive-based functions that include working memory, planning, and inhibition, and which are associated with inattention; and hot affective processes that are associated with delay aversion and impulsive behaviours [

34]. Effective pragmatic communication may also rely on both of these systems. Cool cognitive functions may be required to maintain information about the conversational topic and to produce coherent, well-planned and appropriate conversational speech [

2,

35,

36], whilst affective processes may be required for appropriate turn taking, and to limit excessive talking [

2,

37]. Deficits in one or both of these dimensions may therefore impair pragmatic communication and cause problems with social and peer relationships [

7,

38]. Consistent with this, research has shown that children with elevated symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity have intact knowledge of pragmatics but problems in the executive skills needed to apply it in social contexts [

2,

6,

39].

Impairments in language structure also co-occur with ADHD symptoms across different populations. Deficits in structural components of communication such as the use of syntax and phonology are present in children with ADHD [

2]. Weak literacy skills are also associated with both elevated levels of inattention and hyperactivity in clinical and community samples [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44], with stronger links with inattention [

45,

46,

47,

48]. A possible explanation for this association is that behavioural inattention disrupts the formal acquisition of reading skills through its impact on classroom behaviour, which reduces children’s ability to attend to direct instructions required for learning to read [

49]. This model is supported by evidence that preschool inattention predicts later reading skills independently from other early markers of literacy development such as phoneme awareness and letter knowledge [

40,

41,

50]. Difficulties paying attention may also have a direct effect on the development of structural language skills that are important for literacy development (e.g., phonological processing) [

51,

52,

53]. An alternative possibility is that underlying deficits in executive functions such as working memory underlie both short attention spans and literacy problems [

3,

32,

33].

Pragmatic and structural language problems encompassing poor structural communication and literacy therefore co-occur with the symptoms of ADHD, but evidence for the specificity and strengths of these relationships is mixed. To date, studies have focused on either diagnosed groups or community samples containing large numbers of typically developing children. The present study explored the relationship between these dimensions of impairment across diagnostic categories in a unique sample of struggling learners. The children had difficulties in attention, learning, or memory, and were receiving support from professionals working in children’s services, including speech and language therapists, educational psychologists, school-based special educational needs co-ordinators, mental health practitioners, and paediatricians. Approximately one third had received formal diagnoses (e.g., of ADHD, ASD, or dyslexia) and the remainder had sub-clinical difficulties of varying severity. Based on previous findings of an association between behavioural problems and pragmatic language difficulties we expected behaviour problems to be more highly linked with pragmatic than structural language skills overall, with additional specific associations between behavioural inattention and assessments of structural language skills in literacy.

Assessments included standardised tests of reading, spelling, phonological awareness and vocabulary, as well as parent ratings of children’s behaviour and pragmatic and structural communication skills. Because of the atypicality of this sample, a data driven approach was used to examine the relationships between behaviour and language skills. We sought to identify whether separate dimensions of inattentive and hyperactive behaviour problems were present in the sample, and the extent to which these behaviours were related to poor structural and pragmatic language skills.

4. Discussion

This study explored associations between the behavioural symptoms of ADHD and pragmatic and structural language abilities in a heterogeneous sample of children receiving support for problems in attention, learning, or memory. A bottom-up data driven approach identified dimensions of behaviour and language characterising the sample. This yielded a single dimension of behavioural problems that included inattention, hyperactivity and other behaviour problems commonly associated with ADHD. Although symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity can be diagnostically separate [

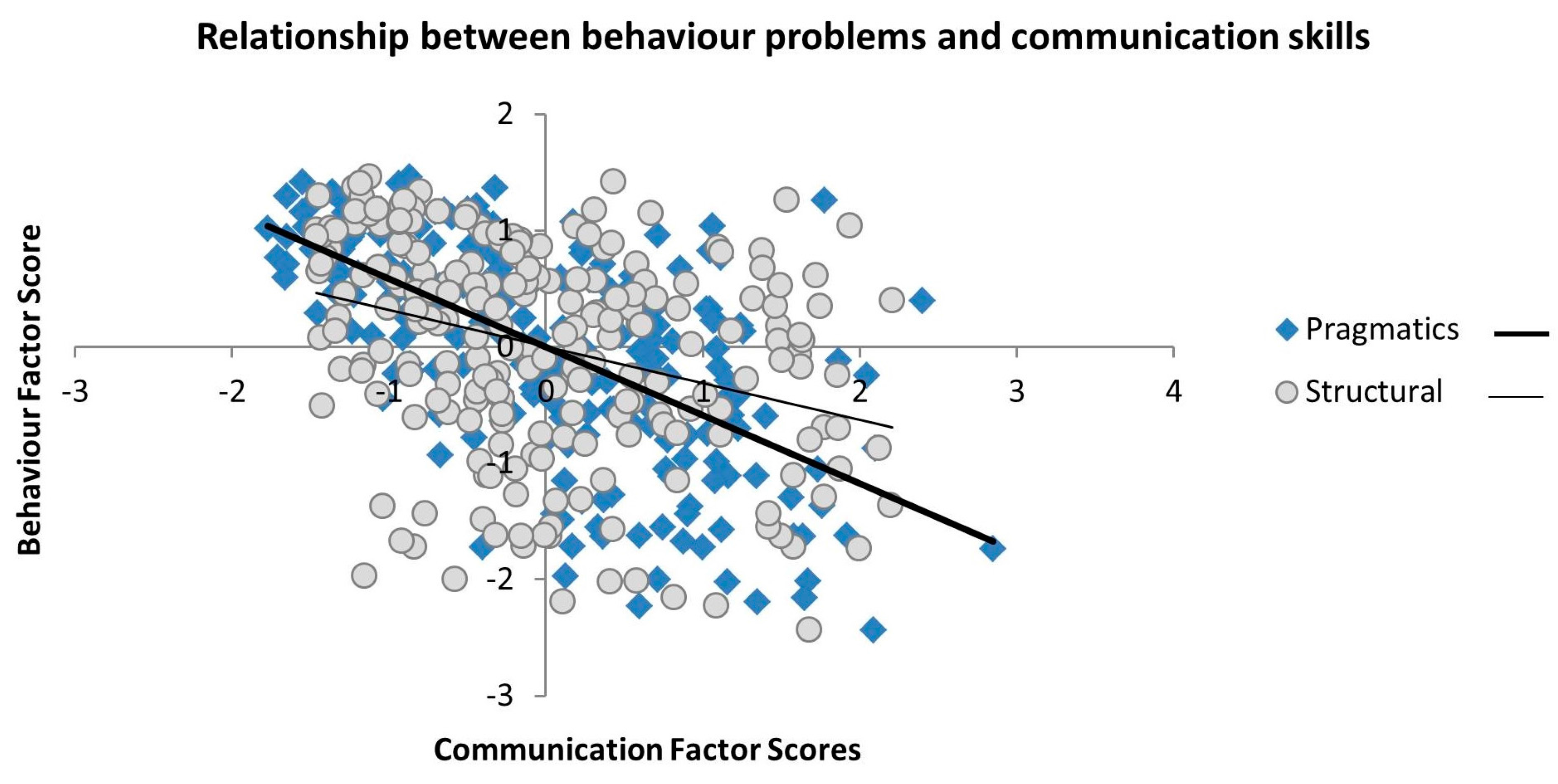

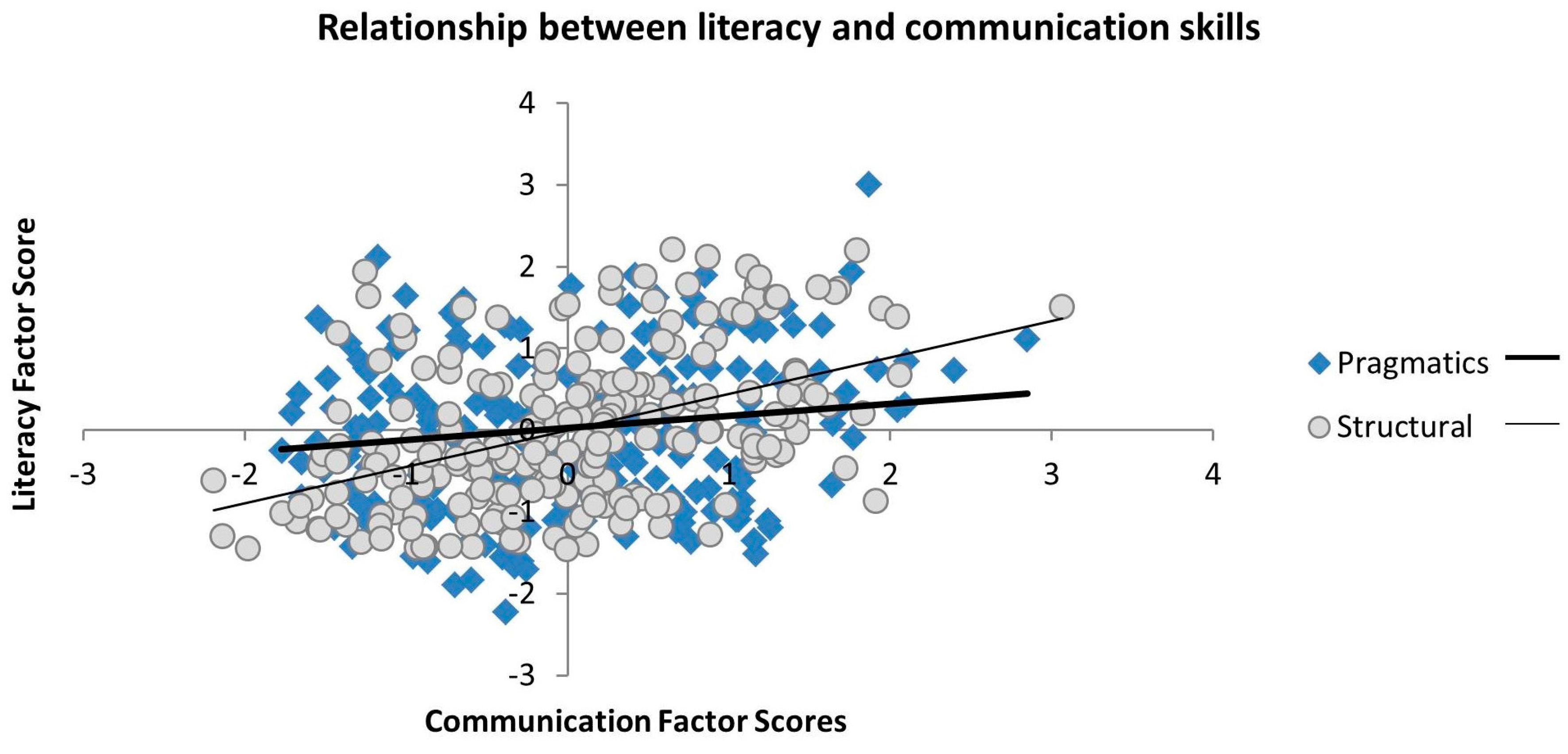

60], it was not possible to differentiate them in the current sample. Three related dimensions of language emerged. One captured pragmatic communication skills and two encompassed children’s use of language structure. These were structural communication and literacy. Behaviour problems were strongly associated with pragmatic aspects of language, but less so with structural communication skills and not at all with literacy.

These differences in the relationship between the pragmatic and structural aspects of language function and behaviour are consistent with the idea that language impairments may have different sources [

22,

25]. Co-occurring behaviour difficulties and pragmatic communication problems may be underpinned by a common deficit in executive functioning. Pragmatic skills such as taking turns in conversation and not talking excessively, and the ability to control hyperactive/impulsive behaviours may both rely on hot executive skills like self-regulation and inhibition [

2,

37]. Likewise, features of social interaction such as monitoring and maintaining appropriate topics of conversation, and planning coherent speech, may draw on the same cool executive functions needed to maintain focussed attention (e.g., working memory) [

61]. Consistent with this interpretation, executive function problems were present in the behaviour ratings in our sample. An alternative explanation is that there is a direct link between poor behaviour and weak pragmatic skills. By this account, difficult behaviour might directly limit opportunities for social interaction at home or school, impairing the development of social language skills [

24,

38]. Our sample had problems with peer relationships, signalling that they may indeed have had fewer opportunities to practice or develop pragmatic language skills.

Impairments in language structure may arise from different or additional sources to pragmatic and behavioural problems. Consistent with this, there was a weaker association between structural communication and behaviour than between pragmatics and behaviour. Moreover, literacy was unrelated to behaviour. This was unexpected given previous evidence linking ADHD symptoms, and in particular inattentive behaviour, with language and reading abilities [

41,

49]. One possibility is that the cognitive deficits limiting the acquisition and development of linguistic knowledge and skills are different to the executive function problems that are affecting behavioural control and social communication in our sample. These additional or alternative deficits might include problems with phonological processing. Supporting this idea, in the current study children’s phonological awareness and abilities in reading and spelling were strongly associated, but there was no link between their behavioural attention problems and phonological skills. Phonological processing skills are important for literacy development [

14] and difficulties with phonological processing influence the acquisition of letter-sound correspondences that are important for learning to read [

27,

40]. Phonological processing impairments are commonly observed in children with SLI who have structural language impairments [

12]. However, children with elevated symptoms of ADHD or pragmatic language difficulties tend to have intact phonological processing skills unless they have co-morbid problems with language structure [

62,

63], suggesting phonological deficits may be more closely associated with broader structural language problems than pragmatic difficulties.

There were stronger links between the parent-reported measures of language and behaviour than between parent-rated behaviour and the direct tests of literacy. This raises the possibility that the associations between parent-rated communication and behaviour simply reflect common variance in subjective reports from parents/carers of children who are receiving support from professional services. Although we cannot rule out this possibility, several features of the data suggest the parent ratings provided meaningful measurements of children’s behaviour and language skills. Firstly, the parent ratings of communicative language were related to the standardised literacy assessments, with a stronger relationship between parent-rated structural communication and direct literacy measures than between pragmatic communication and literacy. Second, these parent-rated communication scores similarly showed different strengths of association with parents’ behaviour ratings. Finally, parents’ views of their children’s learning abilities, as measured by a subscale of the behaviour checklist, correlated with the direct measures of literacy despite there being no other relationships between these measures and other scales on the behaviour checklist. Taken together, the specificity of these links speaks against a common variance in the parent measures underpinning the results.