The Influence of Parental Emotional Neglect on Assault Victims Seeking Treatment for Depressed Mood and Alcohol Misuse: A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Assaults

1.2. Neglectful Parenting

1.3. Models That Consider Impact of Childhood Emotional Neglect

1.4. Summary

1.5. Current Study

2. Experimental Section

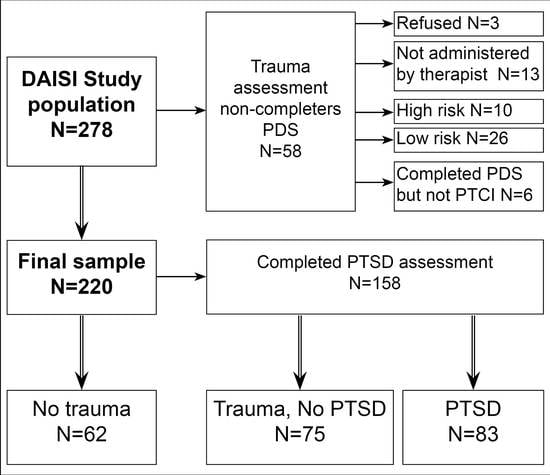

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Sample Characteristics

Stage 1: Correlations and Regressions of Sexual and Physical Assault Variables.

Stage 2: Path Analysis for SA and PA.

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health (ACPMH). Australian Guidelines for the Treatment of Adults with Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Practitioner Guide. Available online: www.acpmh.unimelb.edu.au (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Mayou, R.; Bryant, B.; Ehlers, A. Prediction of psychological outcomes one year after a motor vehicle accident. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalev, A.Y. Acute stress reactions in adults. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 51, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.M.; Beck, G.; Marques, L.; Palyo, S.A.; Clapp, J.D. The structure of distress following trauma: Posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and generalised anxiety disorder. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2008, 117, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, M.L.; Creamer, M.; Pattison, P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma: Understanding comorbidity. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1390–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koss, M.P.; Bailey, J.A.; Yuan, N.P.; Herrera, V.M.; Lichter, E.L. Depression and ptsd in survivors of male violence: Research and training initiatives to facilitate recovery. Psychol. Women Q. 2003, 27, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, A.Y.; Freedman, S.; Peri, T.; Brandes, D.; Shar, T.; Orr, S.P.; Pitman, R.K. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khantzian, E.J. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1997, 4, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briere, J.; Hodges, M.; Godbout, N. Traumatic stress, affect dysregulation, and dysfunctional avoidance: A structural equation model. J. Trauma. Stress 2010, 23, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, D.M.; Mok, D.S.; Briere, J. Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomalogy, and sex differences in the general population. J. Trauma. Stress 2004, 17, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masho, S.W.; Anderson, L. Sexual assault in men: A population-based study of virginia. Violence Vict. 2009, 24, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Personal Safety Survey; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- Talbot, N.L.; Conwell, Y.; O’Hara, M.W.; Stuart, S.; Ward, E.A.; Gamble, S.A.; Watts, A.; Tu, X. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed women with sexual abuse histories: A pilot study in a community mental health centre. J. Nerv. Ment. Disord. 2005, 193, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S.E.; Brecklin, L.R. Sexual assault history and health-related outcomes in a national sample of women. Psychol. Women Q. 2003, 27, 46–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A. Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between ptsd and alcohol abuse: The nature of the association. Addict. Behav. 1998, 23, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewksbury, R. Effects of sexual assaults on men: Physical, mental and sexual consequences. Int. J. Men’s Health 2007, 6, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonne, S.C.; Back, S.E.; Zuniga, C.D.; Randall, C.L.; Brady, K.T. Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Addict. 2003, 12, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinzow, H.M.; Resnick, H.S.; McCauley, J.L.; Amstadter, A.B.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Kilpatrick, D.G. Prevalence and risk of psychiatric disorders as a function of variant rape histories: Results from a national survey of women. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedtke, K.A.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Fitzgerald, M.M.; Zinzow, H.M.; Saunders, B.E.; Resnick, H.S.; Kilpatrick, D.G. A longitudindal investigation of interpersonal violence in relation to mental health and substance use. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.H. Alcohol abuse in individuals exposed to trauma: A critical review. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 120, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuller, G. The serious impact and consequences of physical assault. In Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice; Australian Insitute of Crime: Canberra, Australia, 2015; Volume 496, p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. The Science of Neglect: The Persistent Absence of Responsive Care Disrupts the Developing Brain (Working Paper 12). Available online: http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/reports_and_working_papers/working_papers/wp12/ (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Stoltenborg, M.; Bakersman-Kranenburg, M.J.; van IJzendorn, M.H. The neglect of child neglect: A metanalytic review of prevalence of neglect. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC). Core Info: Emotional Neglect and Emotional Abuse in Preschool Children; NSPCC: Cardiff, UK, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nilly, M.; Haran, D. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2009, 46, 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Dube, S.R.; Williamson, D.F.; Thompson, T.J.; Loo, C.M.; Giles, W.H. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect and childhood dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004, 28, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perry, B.D. Bonding and Attachment in Maltreated Children: Consequences of Emotional Neglect in Childhood. Available online: http://aia.berkeley.edu/strengthening_connections/handouts/perry/Bonding%20and%20Attachment.pdf (accessed on 22 Jule 2015).

- Farrugia, P.L.; Mills, K.L.; Barrett, E.; Back, S.E.; Teesson, M.; Baker, A.; Sannibale, C.; Hopwood, S.; Merz, S.; Rosenfeld, J.; et al. Childhood trauma among individual with co-morbid substance use and posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment. Health Subst. Use 2011, 4, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi-Oliveira, R.; Milnitsky Stein, L. Childhood maltreatment associated with ptsd and emotional distress in low-income adults: The burden of neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2008, 32, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierres, S.E.; Todd, M. The impact of childhood abuse on treatment outcomes of substance users. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1997, 28, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J. Childhood trauma and depression. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2003, 16, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballenger, J.C.; Davidson, R.T.; Lecrubier, Y.; Nutt, D.J.; Marshall, R.D.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Shalev, A.Y.; Yehuda, R. Consensus statement update on posttraumatic stress disorder from the international consensus group on anxiety and depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1994; Volume 3, pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briere, J. Treating adult survivors of severe childhood abuse and neglect: Further development of an integrative model. In The Apsac Handbook on Childhood Maltreatment, 2nd ed.; Myers, J.E.B., Berliner, L., Briere, J., Hendrix, C.T., Jenny, C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis, M.D. The psychobiology of neglect. Child Maltreat. 2005, 10, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, B.D.; Pollard, D. Altered brain development following global neglect in early childhood. In Society for Neuroscience: Proceedings from annual meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 25–29 October 1997.

- Bailey, K.A.; Webster, R.A.; Baker, A.L.; Kavanagh, D.J. Posttraumatic stress profiles among a treatment sample with comorbid depression and alcohol use problems. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012, 31, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tull, M. Rates of PTSD from Rape and Other Forms of Sexual Assault. Available online: http://ptsd.about.com/od/prevalence/a/sexassault.htm (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Dunmore, E.; Clark, D.M.; Ehlers, A. Cognitive factors involved in the onset and maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after physical or sexual assault. Behav. Res. Ther. 1999, 37, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patock-Peckham, J.A.; Morgan-Lopez, A.A. College drinking behaviours: Mediational links between parenting styles, parental bonds, depression and alcohol problems. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007, 21, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; Hunt, S.; Lewin, T.; Carr, V.J.; Connolly, J. A randomised controlled trial of CBT for co-existing depression and alcohol problems: Short-term outcome. Addiction 2010, 105, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Kay-Lambkin, F.J.; Hunt, S.A.; Lewin, T.J.; Carr, V.J.; McElduff, P. Randomised controlled trial of MICBT for co-existing alcohol misuse and depression: Outcomes to 36-months. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2014, 46, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Centre (NHMRC). Australian Alcohol Guidelines: Health Risks and Benefits; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2001.

- Foa, E.B.; Cashman, L.; Jaycox, L.; Perry, K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol. Assess. 1997, 9, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.; Roussos, J.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Mitchell, P.; Wilhelm, K.; Austin, M.P. The development of a refined measure of dysfunctional parenting and assessment of its relevance in patients with affective disorders. Psychol. Assess. 1997, 27, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. The Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed.; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J.B.; Aasland, O.G.; Babor, T.F.; de le Fuente, J.R.; Grant, M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). Who collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction 1993, 88, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babor, T.F.; Higgins-Biddle, J.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Monteiro, M.G. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care, 2nd ed.; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell, T.; Sitharthan, T.; McGrath, D.; Lang, E. The measurement of alcohol dependence and impaired control in community samples. Addiction 1994, 89, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, T.; Murphy, D.; Hodgson, R. The severity of alcohol dependence questionnaire: Its use, reliability and validity. Addiction 1983, 78, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobell, L.C.; Sobell, M.B. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In Review of Diagnostic and Screeing Instruments for Alcohol and Other Drug Use and Other Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed.Dawe, S., Loxton, N.J., Hides, L., Kavanagh, D.J., Mattick, R.P., Eds.; Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra, Australia, 2002; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell, L.C.; Sobell, M.B. Assessing Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers, 2nd ed.Allen, J.P., Wilson, V.B., Eds.; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2003.

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Spss for Window, version 19; Internationational Business Machines; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010.

- Gladstone, G.; Parker, G.; Wilhelm, W.; Mitchell, P.; Austine, M.P. Characteristics of depressed patients who report childhood sexual abuse. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vranceanu, A.; Hobfoll, S.E.; Johnson, R.J. Child multi-type maltreatment and associated depression and ptsd symptoms: The role of social support and stress. Child Abuse Negl. 2007, 31, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A.; McAtamney, A. Key Issues in Alcohol-Related Violence; Australian Institute of Criminology: Canberra, Australia, 2009; pp. 1–8.

- Abler, L.A.; Sikkema, K.J.; Watt, M.H.; Eaton, L.A.; Choi, K.W.; Kalichman, S.C.; Skinner, D.; Pieterse, D. Longitudinal cohort study of depression, post-traumatic stress, and alcohol use in south african women who attend alcohol serving venues. BioMed Cent. Psychiatry 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, J.P.; Wardell, J.D.; Colder, C.R. Reciprocal associations between ptsd and alcohol involvement in college: A three year trait-state-error analysis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.A.; Ramsey, S.E.; Kahler, C.W.; Palm, K.M.; Monti, P.M.; Abrams, D. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural treatment for depression versus relaxation training for alcohol-dependent individuals with elevated depressive symptoms. J. Stud. Alcohol 2011, 72, 268–296. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan, C.J.; Moos, R.H.; Holahan, C.K.; Cronkite, R.C.; Randall, P.K. Drinking to cope and alcohol use in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trauma Event Type | n (%) | Gender | Finished School | Welfare Recipient | Marital Status (Single) | PTSD Diagnosis | Depression Onset | Alcohol Initiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| No Trauma | 62 (28.2%) | a M 33 (53.2%) | 24 (39.3%) | 22 (35.5%) | 17 (27.4%) | -- | 29.7 years (14.2) | 16.0 years (5.3) |

| b F 29 (46.8%) | ||||||||

| Trauma Experienced | 158 (71.8%) | a M 80 (50.6%) | 78 (49.7%) | 79 (50.6) | 43 (27.2%) | 83 (52.5%) | 24.7 years (14.3) | 15.1 years (5.1) |

| b F 78 (49.4%) | ||||||||

| Sexual Assault | 74 (38.7%) | a M 19 (25.7%) | 35 (45.9%) | 36 (49.3%) | 20 (25.7%) | 43 (58.1%) | 21.7 years (13.2) | 14.6 years (5.8) |

| b F 55 (74.3%) | ||||||||

| Physical Assault | 84 (44.0%) | a M 42 (50.0%) | 43 (51.2%) | 48 (57.8% | 30 (35.7%) | 48 (57.1%) | 21.7 years (13.0) | 14.5 years (5.2) |

| b F 42 (50.0%) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bailey, K.A.; Baker, A.L.; McElduff, P.; Kavanagh, D.J. The Influence of Parental Emotional Neglect on Assault Victims Seeking Treatment for Depressed Mood and Alcohol Misuse: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm5100088

Bailey KA, Baker AL, McElduff P, Kavanagh DJ. The Influence of Parental Emotional Neglect on Assault Victims Seeking Treatment for Depressed Mood and Alcohol Misuse: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2016; 5(10):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm5100088

Chicago/Turabian StyleBailey, Kylie A., Amanda L. Baker, Patrick McElduff, and David J. Kavanagh. 2016. "The Influence of Parental Emotional Neglect on Assault Victims Seeking Treatment for Depressed Mood and Alcohol Misuse: A Pilot Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 5, no. 10: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm5100088