Self-Assembled Triphenylphosphonium-Conjugated Dicyanostilbene Nanoparticles and Their Fluorescence Probes for Reactive Oxygen Species

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Instruments

2.2. Synthesis of Compound 3

2.3. Synthesis of Compound 2

2.4. Synthesis of Probe 1

2.5. Synthesis of Probe 2

2.6. Synthesis of 1-Ref

2.7. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.8. Determination of Limit of Detection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Self-Assembled Probes 1 and 2

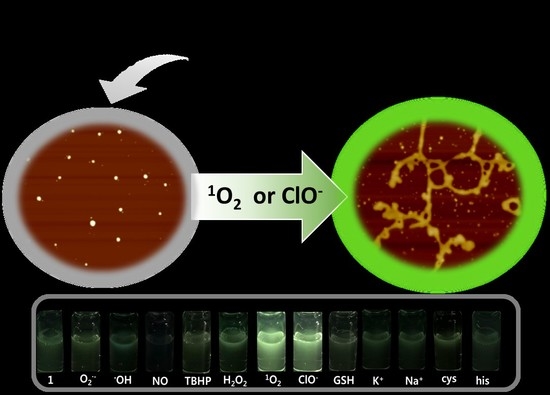

3.2. ROS-Sensing Ability of Self-Assembled Probes 1 and 2 in Aqueous Solution

3.3. ROS-Mediated Fluorescence Turn-On Mechanism of Self-Assembled Probe 1 in Aqueous Solution

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, H.; Qu, D.; Jiang, H.; Fan, W.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y. A supramolecular approach towards strong and tough polymer nanocomposite fibers. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10361–10366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cherumukkil, S.; Vedhanarayanan, B.; Das, G.; Praveen, V.K.; Ajayaghosh, A. Self-assembly of Bodipy-derived extended π-Systems. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 91, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T. Self-assembly of discrete organic nanotubes. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 91, 623–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K.; Nishikawa, M.; Mori, T.; Takeya, J.; Shrestha, L.K.; Hill, J.P. Self-assembly as a key player for materials nanoarchitectonics. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tian, T.; Zhang, T.; Cai, X.; Lin, Y. Advances in biological applications of self-assembled DNA tetrahedral nanostructures. Mater. Today 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-T.; Chen, Z.; Goei, R.; Wu, W.; Lim, T.-T. Magnetically recyclable Bi/Fe-based hierarchical nanostructures via self-assembly for environmental decontamination. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 12736–12746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Hu, L.; Du, W.; Tian, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Wu, J.; Uvdal, K.; Tian, Y. Mitochondria-targeted iridium (III) complexes as two-photon fluorogenic probes of cysteine/homocysteine. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 255, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.H.; Todd, M.H.; Rutledge, P.J. Recent advances in macrocyclic fluorescent probes for ion sensing. Molecules 2017, 22, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, K.; Jana, D.; Ghorai, B.K.; Jana, N.R. Functionalized chitosan with self-assembly induced and subcellular localization-dependent fluorescence ‘switch on’ property. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 5774–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, Y.; Tong, B.; Zhi, J.; Dong, Y. Tunable fluorescence upon aggregation: Photophysical properties of cationic conjugated polyelectrolytes containing AIE and ACQ units and their use in the dual-channel quantification of heparin. Sens. Actuators B 2014, 197, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tian, X.; Shin, I.; Yoon, J. Fluorescent and luminescent probes for detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4783–4804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Xu, M.; Jiang, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q. A simple fluorescein derived colorimetric and fluorescent ‘off-on’ sensor for the detection of hypochlorite. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 4562–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Hou, J.-T.; Yang, J.; Yu, X.-Q. A tumor-specific and mitochondria-targeted fluorescent probe for real-time sensing of hypochlorite in living cells. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5539–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavelescu, L.A.; Iordache, M.-M.; Savopol, T.; Kovacs, E.; Moisescu, M.G. A new technique for evaluating reactive oxygen species generation. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2015, 5, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, X.; Li, Y.; Niu, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, X.; Tang, B. Small-Molecule Fluorescent Probes for Imaging and Detection of Reactive Oxygen, Nitrogen, and Sulfur Species in Biological Systems. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Wang, F.; Qiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Benzothiazole-based fluorescent sensor for hypochlorite detection and its application for biological imaging. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 243, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, Q.; Li, Q.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y. A new rhodamine-based fluorescent probe for the detection of singlet oxygen. Chem. Lett. 2015, 44, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-W.; Xu, S.; Wang, P.; Hu, X.-X.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, X.-B.; Tan, W. An efficient two-photon fluorescent probe for monitoring mitochondrial singlet oxygen in tissues during photodynamic therapy. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12330–12333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Cho, E.J.; Kwon, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S.E. A singlet oxygen photosensitizer enables photoluminescent monitoring of singlet oxygen doses. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulay, S.V.; Choi, M.; Jang, Y.J.; Kim, Y.; Jon, S.; Churchill, D.G. Enhanced Fluorescence Turn-on Imaging of Hypochlorous Acid in Living Immune and Cancer Cells. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 9642–9648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Zhu, L.; Cao, D.; Li, L. Synthesis, characterization and fluorescence “turn-on” detection of BSA based on the cationic poly(diketopyrrolopyrrole-co-ethynylfluorene) through deaggregating process. Sens. Actuators B 2016, 231, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifu, N.; Dong, X.; Li, D.; Sun, X.; Zebibula, A.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, G.; Qian, J. Aggregation-induced emission nanoparticles as photosensitizer for two-photon photodynamic therapy. Mater. Chem. Front. 2017, 1, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- En, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yan, C.; Wang, T.; Cheng, H.; Cheng, X. Self-assembly, AIEE and mechanochromic properties of amphiphilic α-cyanostilbene derivatives. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 5253–5259. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, X. Hyperbranched conjugated polymers containing 1,3-butadiene units: Metal-free catalyzed synthesis and selective chemosensors for Fe3+ ions. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 12269–12276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Yin, G.; Quan, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, R. A colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent probe for ClO- targeting in mitochondria and its application in vivo. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Jin, H.; Park, J.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.; Kim, S.K.; Bae, J.; Jung, J.H. Mitochondria-targeting self-assembled nanoparticles derived from triphenylphosphonium-conjugated cyanostilbene enable site-specific imaging and anticancer drug delivery. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 1082–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay-Agbozo, S.; Street, S.; Kispert, L.D. The carotenoid bixin: Optical studies of aggregation in polar/water solvents. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2018, 362, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Cho, H.; Chen, H.H.; Panagia, M.; Sosnovik, D.E.; Josephson, L. Fluorescent and radiolabeled triphenylphosphonium probes for imaging mitochondria. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 10361–10363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herrikhuyzen, J.; Willems, R.; George, S.J.; Flipse, C.; Gielen, J.C.; Christianen, P.C.M.; Schenning, A.P.H.J.; Meskers, S.C.J. Atomic Force Microscopy Nanomanipulation of Shape Persistent, Spherical, Self-Assembled Aggregates of Gold Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 6501–6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, J.J.; Wong, N.-K.; Lu, M.-Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, S.; Zhao, A.Q.; Gao, P.; Kao, R.Y.-T.; Shen, J.; Yang, D. HKOCl-3: A fluorescent hypochlorous acid probe for live-cell and in vivo imaging and quantitative application in flow cytometry and a 96-well microplate assay. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 2094–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Yu, P.; Sun, M.; Yan, X.; Guo, J.-P.; Guo, W. Imaging lysosomal highly reactive oxygen species and lighting up cancer cells and tumors enabled by a Si-rhodamine-based near-infrared fluorescent probe. Biomaterials 2017, 133, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njeri, C.W.; Ellis, H.R. Shifting redox states of the iron center partitions CDO between crosslink formation or cysteine oxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 558, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Zhang, F.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Ding, H.; Ding, L. Sensitive detection of biothiols and histidine based on the recovered fluorescence of the carbon quantum dots-Hg (II) system. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 859, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagadevan, A.; Hwang, K.C.; Su, M.-D. Singlet oxygen-mediated selective C–H bond hydroperoxidation of ethereal hydrocarbons. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, W.; Lim, N.Y.; Choi, H.; Seo, M.L.; Ahn, J.; Jung, J.H. Self-Assembled Triphenylphosphonium-Conjugated Dicyanostilbene Nanoparticles and Their Fluorescence Probes for Reactive Oxygen Species. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8121034

Choi W, Lim NY, Choi H, Seo ML, Ahn J, Jung JH. Self-Assembled Triphenylphosphonium-Conjugated Dicyanostilbene Nanoparticles and Their Fluorescence Probes for Reactive Oxygen Species. Nanomaterials. 2018; 8(12):1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8121034

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Wonjin, Na Young Lim, Heekyoung Choi, Moo Lyong Seo, Junho Ahn, and Jong Hwa Jung. 2018. "Self-Assembled Triphenylphosphonium-Conjugated Dicyanostilbene Nanoparticles and Their Fluorescence Probes for Reactive Oxygen Species" Nanomaterials 8, no. 12: 1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8121034