Influence of Efficient Thickness of Antireflection Coating Layer of HfO2 for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cell

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Texturing of the Surface of the Silicon Wafer

2.2. Preparation of Precursor and Deposition of ARC Layer

2.3. Characterizations

2.4. PC1D Simulating Tool

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Crystallinity and Morphological Features

3.2. Optical Properties

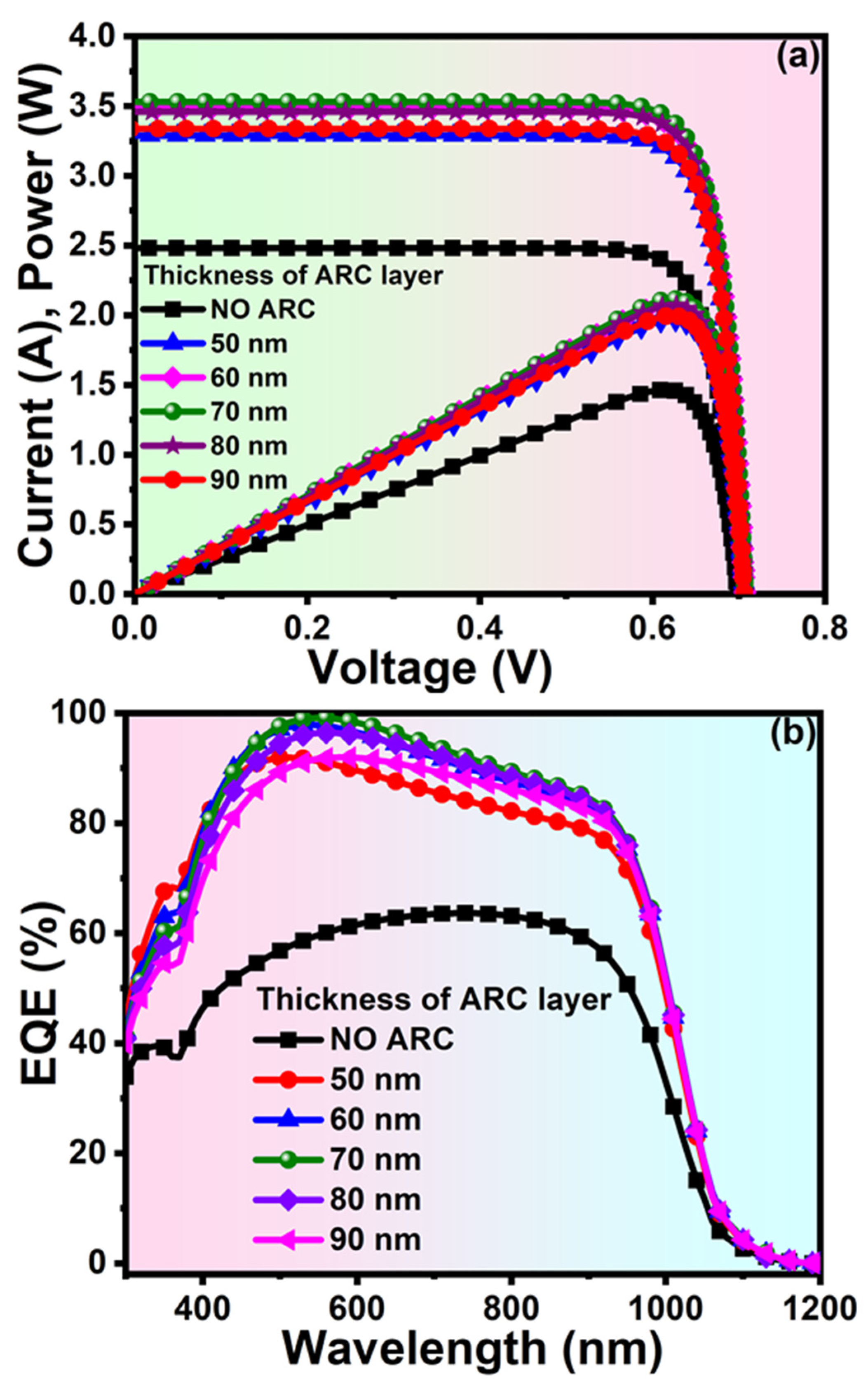

3.3. Photovoltaic Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarkın, A.S.; Ekren, N.; Sağlam, Ş. A review of anti-reflection and self-cleaning coatings on photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy 2020, 199, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Sadanand; Dubey, P.; Lohia, P.; Dwivedi, D.K.; Fouad, H.; Akhtar, M.S. Simulation Engineering in Quantum Dots for Efficient Photovoltaic Solar Cell Using Copper Iodide as Hole Transport Layer. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2021, 16, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Li, Y.; Que, Z.; Zhai, S.; Feng, Y.; Chu, L.; Li, X. Low Temperature VOx Hole Transport Layer for Enhancing the Performance of Carbon-Based Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2021, 16, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; Son, Y.-H.; Lee, H.-R.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. A stable gel electrolyte based on poly butyl acrylate (PBA)-co-poly acrylonitrile (PAN) for solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 754, 137756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, C.; Cuevas, A.; De Wolf, S. High-efficiency crystalline silicon solar cells: Status and perspectives. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 1552–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, D.K.; KC, D.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. Vertically Arranged Zinc Oxide Nanorods as Antireflection Layer for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cell: A Simulation Study of Photovoltaic Properties. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Kim, I.T.; Choi, H.W. Characteristics of Perovskite Solar Cells with ZnGa2O4: Mn Phosphor Mixed Polyvinylidene Fluoride Down-Conversion Layer. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2021, 16, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, D.; Shah, D.K.; Alanazi, A.M.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. Impact of Different Antireflection Layers on Cadmium Telluride (CdTe) Solar Cells: A PC1D Simulation Study. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 2199–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.E.; Doney, L.M.; Johnson, J.R. Some Properties of Hafnium Oxide, Hafnium Silicate, Calcium Hafnate, and Hafnium Carbide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1954, 37, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Vanderbilt, D. First-principles study of structural, vibrational, and lattice dielectric properties of hafnium oxide. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 233106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuhaili, M.F. Optical properties of hafnium oxide thin films and their application in energy-efficient windows. Opt. Mater. 2004, 27, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsenko, V.A.; Perevalov, T.V.; Islamov, D.R. Electronic properties of hafnium oxide: A contribution from defects and traps. Phys. Rep. 2016, 613, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukli, K.; Ritala, M.; Sundqvist, J.; Aarik, J.; Lu, J.; Sajavaara, T.; Hårsta, A. Properties of hafnium oxide films grown by atomic layer deposition from hafnium tetraiodide and oxygen. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 5698–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.A.; Luna-Velasco, A.; Boitano, S.A.; Shadman, F.; Ratner, B.D.; Barnes, C.; Sierra-Alvarez, R. Cytotoxicity and physicochemical properties of hafnium oxide nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dole, S.L.; Hunter, O.; Wooge, C.J. Elastic Properties of Monoclinic Hafnium Oxide at Room Temperature. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1977, 60, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukli, K.; Aarik, J.; Ritala, M.; Uustare, T.; Sajavaara, T.; Lu, J.; Leskelä, M. Effect of selected atomic layer deposition parameters on the structure and dielectric properties of hafnium oxide films. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 5298–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Kang, L.; Qi, W.-J.; Nieh, R.; Jeon, Y.; Onishi, K.; Lee, J.C. Ultrathin hafnium oxide with low leakage and excellent reliability for alternative gate dielectric application. In International Electron Devices Meeting 1999; Technical Digest (Cat. No. 99CH36318); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J. High dielectric constant oxides. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 28, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, S.; Lu, H.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, G.; Wu, L.; Feng, L. Study of CdTe/ZnTe composite absorbing layer deposited by pulsed laser deposition for CdS/CdTe solar cell. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2017, 67, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, K.-H.; Lin, Q.; Chou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, H.; Qi, P.; Fan, Z. Low-Cost, Flexible, and Self-Cleaning 3D Nanocone Anti-Reflection Films for High-Efficiency Photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2805–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.B.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, S.L. Annealing influence on optical performance of HfO2 thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 152552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, C.L.; Mihaescu, C.I.; Bala, D.; Gifu, I.C.; Ninciuleanu, C.M.; Burlacu, S.G.; Petcu, C.; Vladu, M.-G.; Ghebaur, A.; Stroea, L.; et al. Novel Hydrophobic Nanostructured Antibacterial Coatings for Metallic Surface Protection. Coatings 2022, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; KC, D.; Muddassir, M.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. A simulation approach for investigating the performances of cadmium telluride solar cells using doping concentrations, carrier lifetimes, thickness of layers, and band gaps. Sol. Energy 2021, 216, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; KC, D.; Kim, T.-G.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. Influence of minority charge carrier lifetime and concentration on crystalline silicon solar cells based on double antireflection coating: A simulation study. Opt. Mater. 2021, 121, 111500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmaz, I.; Mandong, A.M.; Uzum, A. Solution-based hafnium oxide thin films as potential antireflection coating for silicon solar cells. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; KC, D.; Kim, T.-G.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. In-search of efficient antireflection layer for crystalline silicon Solar cells: Optimization of the thickness of Nb2O5 thin layer. Eng. Sci. 2022, 18, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Bhopal, M.F.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, A.R.; Kim, H.J.; Rehman, M.A.; Lee, S.H. Effect of additional HfO2 layer deposition on heterojunction c-Si solar cells. Energy Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Son, D.-Y.; Bae, K.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Park, N.-G. Effects of Seed Layer on Growth of ZnO Nanorod and Performance of Perovskite Solar Cell. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 10321–10328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, D.; Shah, D.K.; Akhtar, M.S.; Park, M.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B.; Pant, B. Numerical Investigation of Graphene as a Back Surface Field Layer on the Performance of Cadmium Telluride Solar Cell. Molecules 2021, 26, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, G.; Rashid, M.J.; Mahmood, Z.H.; Hoq, M.; Rahman, M. Investigation of the impact of different ARC layers using PC1D simulation: Application to crystalline silicon solar cells. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2018, 12, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haug, H.; Olaisen, B.R.; Nordseth, Ø.; Marstein, E.S. A Graphical User Interface for Multivariable Analysis of Silicon Solar Cells Using Scripted PC1D Simulations. Energy Procedia 2013, 38, 1876–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lv, J.; Bao, Y.; Xuan, R.; Sun, S.; Sneck, S.; Li, S.; Modanese, C.; Savin, H.; Wang, A.; et al. Data of the recombination loss mechanisms analysis on Al2O3 PERC cell using PC1D and PC2D simulations. Data Brief 2017, 11, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, G. Photoelectric Conversion Performance of Composite Perovskite Solar Cell Device and Its Application in Photovoltaic Building. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2021, 16, 1492–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KC, D.; Shah, D.K.; Shrivastava, A. Computational study on the performance of zinc selenide as window layer for efficient GaAs solar cell. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 2580–2583. [Google Scholar]

- Naim, H.; Shah, D.K.; Bouadi, A.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y. An in-depth optimization of thickness of base and emitter of ZnO/Si heterojunction based crystalline silicon solar Cell: A simulation method. J. Electron. Mater. 2022, 51, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiatrowski, A.; Obstarczyk, A.; Mazur, M.; Kaczmarek, D.; Wojcieszak, D. Characterization of HfO2 Optical Coatings Deposited by MF Magnetron Sputtering. Coatings 2019, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai, D.; Guo, X.; Fan, J. Identification of luminescent surface defect in SiC quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 053115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.pveducation.org/pvcdrom/characterisation/bulk-lifetime (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Hossain, M.A.; Khoo, K.T.; Cui, X.; Poduval, G.; Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Hoex, B. Atomic layer deposition enabling higher efficiency solar cells: A review. Nano Mater. Sci. 2019, 2, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; KC, D.; Parajuli, D.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. A Computational Study of Carrier lifetime, Doping Concentration, and Thickness of Window layer for GaAs Solar Cell based on Al2O3 antireflection layer. Sol. Energy 2022, 234, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; Choi, J.; KC, D.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Yang, O.-B. Refined optoelectronic properties of silicon nanowires for improving photovoltaic properties of crystalline solar cells: A simulation study. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 2784–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Tate, K.; Ebong, A. Generalized analysis of the impact of emitter sheet resistance on silicon solar cell performance. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 54, 08KD20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.F.; Gao, L.K.; Xie, Y.; Tang, T.Y.; Tang, Y.L. Ferromagnetic and Antiferromagnetic Properties of Perovskite Solar Cell Materials. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2021, 16, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, Y.-H.; Kang, S.-J. Effects of Working Pressure on Structural and Optical Properties of HfO2 Thin Films. J. Korea Inst. Electron. Commun. Sci. 2017, 12, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz, Z.; Husein, S.; Saive, R. Thin silicon interference solar cells for targeted or broadband wavelength absorption enhancement. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 4324–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushasree, P.M.; Bora, B. Chapter 1: Silicon Solar Cells. In Solar Energy Capture Materials; RSC Publishing: Piccadilly, London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.pveducation.org/pvcdrom/solar-cell-operation/fill-factor (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Han, H.-V.; Lin, C.-C.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Chen, H.-C.; Chen, K.-J.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Yu, P. A Highly Efficient Hybrid GaAs Solar Cell Based on Colloidal-Quantum-Dot-Sensitization. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alnuaimi, A.; Almansouri, I.; Saadat, I.; Nayfeh, A. High performance graphene-silicon Schottky junction solar cells with HfO2 interfacial layer grown by atomic layer deposition. Sol. Energy 2018, 164, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Lin, T.; Letha, A.J.; Hwang, H.-L.; Kyznetsov, F.A.; Smirnova, T.P.; Kaichev, V.V. Advanced passivation techniques for Si solar cells with high-κ dielectric materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 123905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Device area | 100 cm2 |

| Front surface texture depth | 3 μm |

| The thickness of the Si solar cell | 150 μm |

| Dielectric constant | 11.9 |

| Energy bandgap | 1.124 eV |

| Background doping p-type | 5 × 1016 cm−3 |

| First front diffusion n-type | 3 × 1018 cm−3 |

| Refractive index | 3.42 |

| Excitation mode | Transient |

| Temperature | 25 °C |

| Other parameters | An internal model of PC1D |

| Primary light source | AM 1.5D spectrum |

| Bulk recombination | 10 μs |

| Constant intensity | 0.1 W/cm2 |

| Thickness of ARC Layer (nm) | Average Reflectance | Refractive Index | Isc (A) | Voc (V) | Pmax (W) | FF (%) | Efficiency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Simulation | Experimental | Simulation | ||||||

| Bare Si | 22.61 | 36.12 | 1.52 | -- | 2.28 | 0.642 | 1.22 | 69.80 | 12.27 |

| Texture Si | 10.51 | -- | 1.88 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 50 | -- | 15.76 | -- | 2.70 | 3.28 | 0.705 | 1.965 | 84.66 | 19.65 |

| 60 | 7.44 | 11.27 | 2.14 | 2.28 | 3.48 | 0.707 | 2.085 | 84.64 | 20.85 |

| 70 | 6.33 | 9.45 | 2.30 | 2.95 | 3.52 | 0.707 | 2.115 | 84.67 | 21.15 |

| 80 | 8.35 | 11.80 | 2.04 | 1.70 | 3.46 | 0.707 | 2.072 | 84.66 | 20.72 |

| 90 | -- | 14.85 | -- | 1.52 | 3.33 | 0.706 | 2.995 | 84.64 | 19.95 |

| Types of Solar Cell | Isc (A) | Voc (V) | FF (%) | Efficiency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene/HfO2/Si | 3.34 | 0.450 | 56.0 | 9.10 | [49] |

| HfO2/Si | 3.85 | 0.723 | 74.5 | 20.75 | [27] |

| HfO2/Si | 3.85 | 0.720 | 73.6 | 20.50 | [27] |

| HfO2/Si | 3.63 | 0.730 | 67.1 | 15.54 | [50] |

| HfO2/Si | 3.52 | 0.707 | 84.67 | 21.15 | This work |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, D.K.; KC, D.; Umar, A.; Algadi, H.; Akhtar, M.S.; Yang, O.-B. Influence of Efficient Thickness of Antireflection Coating Layer of HfO2 for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cell. Inorganics 2022, 10, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics10100171

Shah DK, KC D, Umar A, Algadi H, Akhtar MS, Yang O-B. Influence of Efficient Thickness of Antireflection Coating Layer of HfO2 for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cell. Inorganics. 2022; 10(10):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics10100171

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Deb Kumar, Devendra KC, Ahmad Umar, Hassan Algadi, Mohammad Shaheer Akhtar, and O-Bong Yang. 2022. "Influence of Efficient Thickness of Antireflection Coating Layer of HfO2 for Crystalline Silicon Solar Cell" Inorganics 10, no. 10: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics10100171