1. Introduction

In casual conversation, people often say that beer from a bottle tastes better than from a can (e.g., Dredge, 2014 [

1]). But how is such a difference to be explained? One possibility is that the packaging conveys some sort of taint on the contents (e.g., as was famously the case for tinned tomatoes; see Rosenbaum, 1979 [

2]). Alternatively, however, one might hypothesize some difference (e.g., in oxygen) introduced by bottling/canning (see also Wietstock, Glattfelder, Garbe, and Methner, 2016 [

3]). More interestingly, though, is the possibility that the packaging may exert some sort of psychological impact over people’s perception of the product itself (see Hine, 1995 [

4]; Spence, 2016 [

5]; Spence and Piqueras-Fiszman, 2012 [

6]; Velasco et al., 2016 [

7], for reviews of the psychological influence of packaging on product perception). Notably though, most of the research on the factors that influence beer perception and preference has been focused on the sensory and hedonic properties of the beer itself. In contrast, far less research has been conducted in terms of the influence of extrinsic factors associated with the beer such as its presentation format or label (e.g., Aquilani et al., 2015 [

8]; Carvalho et al., 2016 [

9]). Nevertheless, it is known that the consumer acceptance of, preference for, and perceived flavour of food and drink products are influenced by their packaging (Piqueras-Fiszman and Spence, 2015 [

10]; Sester et al., 2013 [

11]; Silva et al., 2017 [

12]).

In particular, a product’s packaging has been shown to influence the consumers’ emotional reactions towards, and semantic associations with, a beer (Sester et al., 2013 [

11]). The term ‘image mold’ was first introduced by Louis Cheskin to describe the fact that certain arbitrary packaging formats/shapes come to be associated with specific brands/product categories (Cheskin, 1957 [

13]; see Spence, 2016 [

5], for a review). One of the classic examples here is the Wishbone Salad dressing bottle. The wide, round shape of this shouldered bottle has come to define the packaging shape for the category since its introduction (see Velasco et al., 2016 [

7], for a review). The classic Coca-Cola bottle constitutes another iconic image mold (see Gates et al., 2007 [

14]; Prince, 1994 [

15]; Velasco et al., 2016 [

7]), as does the Kikkoman dispenser bottle, and even the Campari Soda bottle developed by the Italian Futurist Fortunato DePero back in 1932 (and still on the shelves today). In terms of the beer category, one can think of the distinctively-shaped steel Sapporo beer can as potentially representing such an image mold, or perhaps the distinctive Brahma beer bottle (see Spence and Piqueras-Fiszman, 2012 [

6], for a review). Hence, when a product is presented in packaging that has an identifiable image mold, it can sometimes act as a cue to the brand of product. Hence, it may well be the brand awareness that is doing the work in terms of modulating people’s perception of the taste/quality of the contents as much as the physical attributes of the packaging itself. The suggestion here is that presenting a product in such a distinctive packaging format, will cue the consumer to the likely product attributes, as much as revealing the brand name of a beer has been shown to do (e.g., Allison and Uhl, 1964 [

16]; Anonymous, 1962 [

17]).

In terms of the psychological sensory impact of packaging on product perception, there could be a number of plausible explanations. On the one hand, one might consider any differences in the visual appearance, sound, or feel of the packaging. There is, after all, an emerging literature showing that very often our feelings about the packaging appear to be transferred to our perception of the contents of that packaging (e.g., Krishna and Morrin, 2008 [

18]). This is known as ‘sensation transference’ (see Spence and Piqueras-Fiszman, 2012 [

6], for a review).

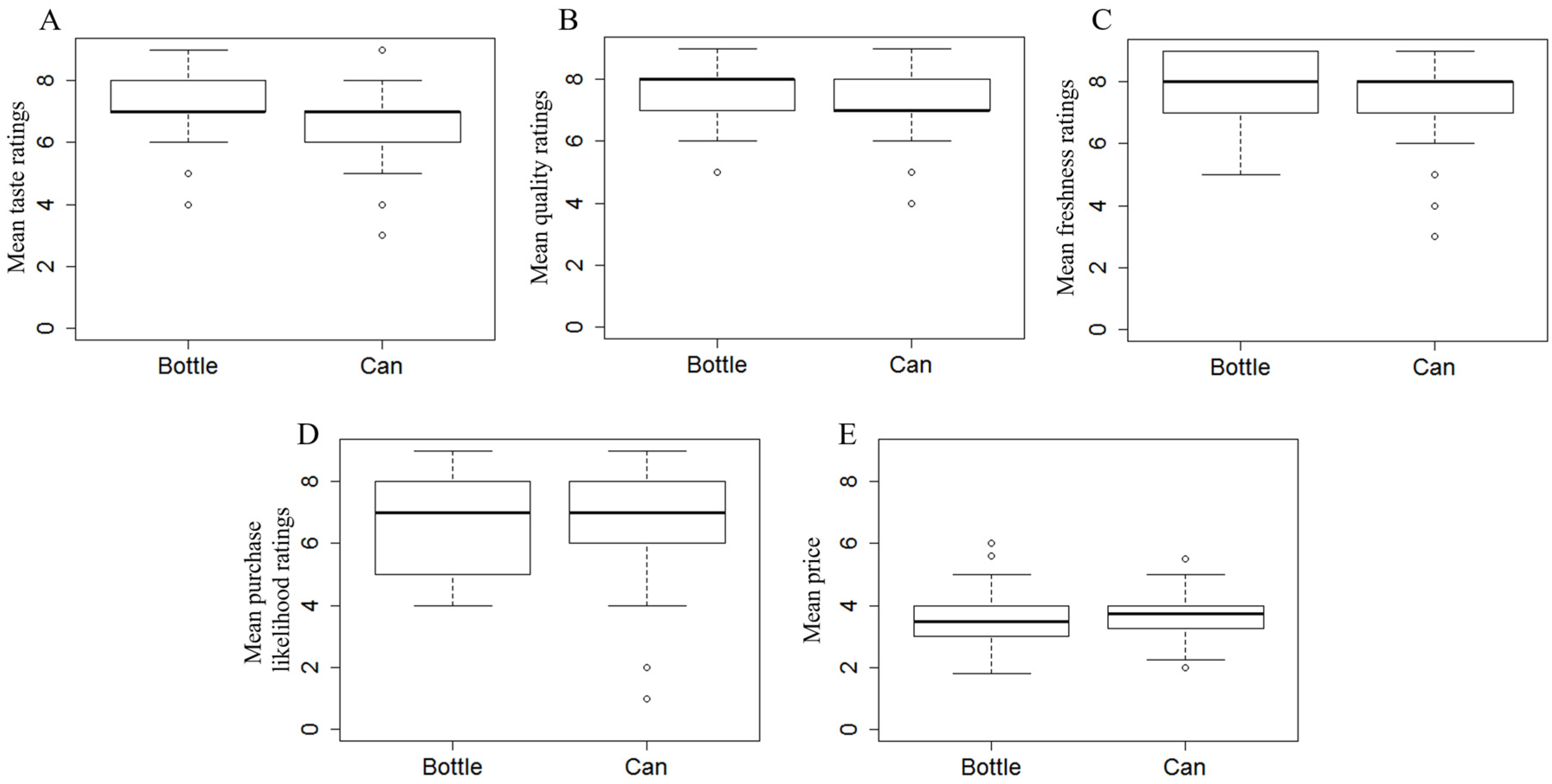

In the present study, we first conducted a preliminary online questionnaire in order to assess people’s preferences for different packaging formats. Next, a between-participants experiment was conducted at the 2016 Edinburgh Science Festival in order to determine what impact, if any, the type of receptacle (i.e., the packaging) had on the perceived taste of beer. Finally, we collected data in a small follow-up control study to check that when tasted blind, people showed no preference for a specific packaging format. In the main part of the study (the second stage), one group of participants was given a plastic cup of beer to taste that they saw being poured from a bottle. Another group of participants also rated beer from a plastic cup, but in this case they saw the beer being poured from a can instead (see

Figure 1). Importantly, the beer was from the same batch (donated by Barney’s Beer in Edinburgh, a small micro-brewery; see

http://barneysbeer.co.uk/) so that all that varied was the receptacle in which the drink was served and consumed. That said, the participants were encouraged to pick up the bottle or can in order to inspect the label before rating the beer.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study support the folk notion that beer tastes better from a bottle than from a can (see Spence, 2016 [

5]; Spence and Piqueras-Fiszman, 2012 [

6], for reviews). The packaging in which the beer was served in the present study was shown to exert a significant influence over the perceived taste of the beer, even though the beer itself was tasted from the same plastic cup in all cases. One can only imagine how much more pronounced the effects of packaging on taste may have been had participants tasted the beer direct from the packaging (i.e., bottle vs. can). Be aware though, that this kind of design would likely also introduce additional variability in terms of aroma perception given the differing opening formats of bottles versus cans (see Spence, 2016 [

21]). Intriguingly, a consistent trend for the bottled beer to be preferred were also demonstrated on perceived quality (though they just failed to reach statistical significance with the convenience sample collected here, thus, potentially deserving follow-up in future research). Here, it is important to consider whether differences in packaging material (e.g., glass vs. tin, therefore potentially their texture) or weight were doing the work in terms of driving the perceived differences in taste, or rather if it was the ‘image mold’ that was critical (Hine, 1995 [

4]; Spence, 2016 [

5]). It is, of course, possible that both factors may have contributed to the effects seen here.

Consumers may well have different associations with bottled vs. canned beer (see also Aquilani et al., 2015 [

8]). In fact, one explanation for the significant difference obtained in the present study relates to the fact that the volume manufacturers moved from bottles to cans as the principal beer packaging format during the 1980s and 1990s. This change in packaging format coincided with an increase in ‘off-trade’ sales at the expense of ‘on-trade’, not to mention the rise of the supermarkets as the biggest channel for sales. Relevant here, cans were used by volume brewers and multiple grocers as a source of discounting, and the value of beer in this format declined in real terms over this period. It can be hypothesized then that buyers increasingly came to associate cans as a value pack format. Consequently, when ‘craft beer’ emerged as a category it was predominantly packaged in bottles (a more commercially accessible format for low volume production) and had a premium price and publicity. Thus bottles, which had all but disappeared during the preceding two decades returned with a premium or quality association in the beer category. That said, things look to be changing once again, with cans now being presented as the fresher, more convenient, packaging format by craft brewers (led by those working out of the US; see Kleban and Nickerson, 2011 [

22], for a review of the U.S. craft brewing industry). That said, it would appear to be hard to get this message through to the consumer, except in exceptional cases. The Sapporo can and perhaps also the Heineken can with its asymmetrical coating of tactile paint were particularly innovative in the beer category (see Anonymous, 2011 [

23]; Spence and Piqueras-Fiszman, 2012 [

6]).

While it has long been asserted, at least anecdotally, that the packaging material (or image mold) exerts a significant impact on what consumers have to say about the taste of the contents (Hine, 1995 [

4]), rigorous empirical data in support of such a notion have, until now, been lacking. That said, the last few years have seen growing interest in the impact of the receptacles in which the consumer drinks on their perception of the contents (see Spence and Wan, 2015 [

24], 2016 [

25], for reviews). Indeed, as just mentioned, the results of the present study are especially interesting in the context of the recent drive toward cans being used as the preferred packaging material for North American craft beers these days. Note, however, that given that consumption patterns change across groups of consumers, one may well expected a variation across different groups. For example, Aquilani et al., 2015 [

8] reported that those consumers who have tasted craft beer (who also drink beer frequently and would drink beer alone) tend to prefer this kind of beer over bottled beer.

Alternatively, as mentioned in the introduction, the influence of the product packaging over taste perception could be something to do with the feel of the packaging in the hand. There are undoubtedly salient perceptual differences in compressability/firmness, temperature (or rather thermal diffusivity; see Bergmann Tiest and Kappers, 2009 [

26]), and texture (all of which have been shown to influence taste ratings, e.g., see Biggs et al., 2016 [

27]; Krishna and Morrin, 2008 [

18]; Piqueras-Fiszman and Spence, 2012 [

28]). Perhaps the most noticeable difference though between bottle and can is in terms of their weight. The filled bottle used in the present study weighed in at 560 grams, whereas the can weighed in at 365 grams (there was 330 mL of beer in each packaging format). A growing body of empirical research now shows that adding weight to product packaging can result in an enhancement in people’s perception of the product (e.g., see Gatti et al., 2014 [

29]; Kampfer et al., 2016 [

30]; Piqueras-Fiszman and Spence, 2012 [

31]; Spence and Piqueras-Fiszman, 2011 [

32]).

It is also important to highlight the fact that although the labels for both the bottle and the can used in the present research were the same, there are a number of aesthetic variations between the visual impression of the two packages. For example, not only did the shape differ, but also the colour, and visual texture. Given that such sensory cues have also been shown to influence product perception and choice (e.g., Barnett and Spence, 2016 [

33]; Hekkert, 2006 [

34]; Tu, Yang, and Ma, 2015 [

35]; Tu and Yang, 2016 [

36]), future research may be well advised to try to disentangle the contribution of each element of the packaging to the experience of the product within, in order to increase the generalizability of the results reported here.

The one other element to consider here is whether the bottle and can are perceived visually to have the same weight. There might, for instance, be illusions of volume differences, despite the fact that both containers actually contained the same volume of liquid (cf. Attwood, Scott-Samuel, Stothart, and Munafò, 2012 [

37]; Wansink and van Ittersum, 2003 [

38], 2005 [

39]). Finally, it is perhaps also worth considering the sound associated with opening and pouring from bottles and cans (see Spence and Wang, 2015 [

40], for a review). Once again, this can provide useful information to help the trained consumer distinguish between different beer brands (e.g., see Stummerer and Hablesreiter, 2010 [

41], p. 105, for one particularly impressive example).

5. Conclusions

Taken together, then, the results of the present study demonstrate that the packaging in which a beer is served can influence the perceived taste of the product. Our results also provide support for those companies wanting to promote glass over other packaging materials (e.g., see the

Vidrio es vida campaign by Peldar, highlighting the sonic benefits of glass bottles over other beverage packaging materials; see [

42].) Ultimately though, the decision about which packaging material to use always reflects a trade-off between the cost of different materials/formats, the cost of transportation to market, as well as questions of sustainability and recyclability (Bland, 2008 [

43]; Brilhuis-Meijer and Saxena, 2015 [

44]), not to mention the impact (psychological or otherwise) of packaging material on perceived taste and quality judgments. In premium categories, such as fine wine, many producers clearly feel it worthwhile to make their glass bottles significantly heavier in order to convey the perception of quality (see Piqueras-Fiszman and Spence, 2012 [

28]). Premium beer producers might be well advised to do the same. That said, there have been reports in the North American craft beer market suggesting that people’s perception of canned beer has been on the rise in recent years (see also Elzinga et al., 2015 [

45]). Ultimately, of course, one needs to remain cognizant of the fact that the packaging is but one ‘p’ in the marketing mix (see Murray and O’Neill, 2012 [

46]; Nickels and Jolson, 1976 [

47]). In terms of the managerial implications, the beneficial psychological impact of bottled beer will need to be balanced against the fact that canned beer is roughly 30% cheaper per litre (this figure based on a crude value/volume measure across all brands/skus/promotions/stores, etc.; Nielsen Scantrack, UK, personal communication to AB, 13 September 2016 [

48]). Determining the optimal solution for a craft beer producer will likely need consideration on a case-by-case basis.