Abstract

This paper discusses the uses of the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] in the language of politics. The paper draws examples from political speeches which took place in the Hellenic Parliament during 2011 and discussed the financial situation of Greece during that time. It is suggested that εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] have a high degree of metonymicity since they express ‘stand for’ relations. It is argued that the deictic adverbs have a referential function since they designate a range of concepts, namely, political parties, financial, political, and social situations, the Hellenic Parliament, political ideology, decisions, etc. It is also stated that the temporal and the spatial denotations of εδώ and εκεί are subject to image schemas. In particular, the paper discusses how the Greek deictic adverbs prompt for the image schemas of containment, part for whole, and centre-periphery and suggests that these types of image schemas have a metonymic basis.

Keywords:

politics; political speech; economic crisis; Greece; deictics; space; time; image schemas; metonymicity 1. Introduction

Our language is central to everything we do; more than any other human attribute, language distinguishes us from all the other animals, and without language, there would be no possibility or cultural development (Chomsky and Otero, 2004; p. 3 [1]). According to Beard (2000; p. 5 [2]), politics, as all spheres of social activities, has its own “code”. The idea is that politics broadly refers to people and the lives they lead in organized communities rather than narrowly referring to the battle-ground of conventional party politics that gained popularity during the 1960s (2000; p. 5 [2]).

Brewer’s Dictionary of Politics (1995 [3]) defines the term politician as: “[a] practitioner of the art of politics, essential to the working of human society but frequently despised by those outside the political arena; indeed the word is sometimes a term of abuse”. It has been observed that politicians and other public figures, instead of reporting the truth, tend to claim that the media presents a distorted picture about them (Beard, 2000; p. 17 [2]).

As far as the relation between politics and language is concerned, O’Barr (1976 [4]) suggested that politics and language are interconnected because one determines the other. According to him, when we ordinarily think of language and politics, we come across situations that readily come to mind, and such situations could be described as “involving language” or as “a dependent variable in the relationship” (ibid; p. 6 [4]). According to this idea, language has a political dimension since humans use language in order to communicate with others, express their thoughts and ideas, agree or disagree, discern between friends and foes, shape and/or form identity and ideology, etc.

The present paper discusses how the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] are used by members of the Hellenic Parliament throughout their political speeches. The paper draws examples from political speeches that took place in the Hellenic Parliament during 2011 and discussed the financial situation of Greece during that time.

2. Metonymy and the Language of Politics

Metonymy constitutes a fundamental cognitive “tool”. Taylor (1989; p. 124 [5]) stated that its essence “resides in the possibility of establishing connections between entities which co-occur within a given conceptual structure”. According to Panther and Radden (1999; p. 2 [6]), metonymy is a process in which one conceptual entity, “the target”, is mentally accessible by means of another conceptual entity, “the vehicle”.

Langacker (1993; p. 30 [7]) argued for the indeterminacy of meaning, interpretation, and the radically indexical nature of language, and he stated that “metonymy is basically a reference-point phenomenon […] affording mental access to the desired access”. According to Langacker (2009; p. 46 [8]), grammatical structures are rooted in metonymy because “[…] the information explicitly provided by conventional means does not itself establish the precise connections apprehended by the speaker and the hearer in using an expression”. In this respect, “[e]xplicit indications evoke conceptions that merely provide mental access to elements with the potential to be connected in specific ways, but the details have to be established on the basis of other considerations” (ibid; p. 46 [8]). Langacker stated that grammar is inherently metonymic in the sense that grammatical structures are connected to one another as “indeterminant”. This means that (i) grammar is not autonomous from semantics, (ii) semantics are neither well-delimited nor fully compositional, and (iii) language draws on more general cognitive systems and capacities from which it cannot be neatly separated (ibid; p. 45 [8]).

One of the most important notions encouraging metonymy is the notion of contiguity. Lakoff and Johnson (1989 [9]) and Taylor (1989 [5]) argued that metonymy could be defined as a shift of a word meaning from the entity it stands for to a “contiguous” entity. Various proposals have been developed for the notion of contiguity. Lakoff and Johnson (1989 [9]) claimed that contiguity deals with the whole range of associations that are commonly related to an expression.

Moreover, Dirven (2002; pp. 92, 100 [10]) observed that, in metonymy, two related domains or subdomains are construed as one domain matrix, or “[…] two elements are brought together, they are mapped on one another and form a contiguous system”. As far as metonymic mappings are concerned, Croft (2002; p. 177 [11]) claimed that they occur within a single domain matrix and not across domains (or domain matrices). Domain matrices are seen as the combination of domains, being “simultaneously presupposed by a concept such as ‘human being’” (ibid; p. 168 [11]).

As far as metonymic expressions are concerned, Radden and Kövecses (2007; p. 337 [12]) suggested that speakers can distinguish between what is subjective and objective in virtue of perceptual selectivity. According to this idea, basic meanings can be distinguished from the non-basic ones and vice versa (ibid; p. 353 [12]). Radden and Kövecsces (ibid; pp. 353, 357 [12]) stated that metonymic expressions serve in denoting communicative principles, and in this way, the default metonymic vehicle is selected as the most preferred.

According to Beard (2000 [2]), both metaphor and metonymy constitute a foundational component of political discourse. According to him, a closer look to metaphor and metonymy explains how political language operates. As far as the use of metonymy in politics is concerned, its power became broadly known by the Watergate Scandal (the building that housed the Democratic Party was broken by the supporters of the Republican president Richard Nixon in 1972). Beard claimed that the power of metonymy in politics was highlighted by this political incident because of intertextuality (one text uses reference to another and one main effect is that of allusion) (ibid; p. 19 [2]). Beard observed that, after the Watergate scandal, the suffix “gate” was used to describe all sorts of scandals in most English-speaking countries (ibid; p. 27 [2]).

Applying the afore-mentioned ideas to the language of politics, it is suggested that the Greek deictic adverb εδώ [here] (see example 1) has a metonymic basis because it goes beyond spatial and temporal senses.

1. Εδώ έχουμε μια κυβέρνηση η οποία δεν παρουσίασε ποτέ ένα σχέδιο για την οικονομία. Άλλα λέτε εντός και άλλα εκτός. Μάλλον εσείς ζείτε την Πρωταπριλιά κάθε μέρα. Και βεβαίως είναι δύσκολα. Aλλά εμείς είμαστε εδώ.

[Here we have a government which has never presented a plan for the economy. You express other statements inside and outside (of the Parliament). Maybe you experience April’s fool every day. Of course it is difficult. But we are here.]

In (1), the Greek deictic adverb εδώ [here] does not simply refer to time and place (that is, the actual time the particular statement was uttered in the Hellenic Parliament). Εδώ [here] serves as the anchoring point of the conversational maxims of quantity, quality, relevance, and manner. It is suggested that the speaker uses the deictic εδώ without giving more information in order to refer to a particular political party, which also happens to be the governing party of Greece.

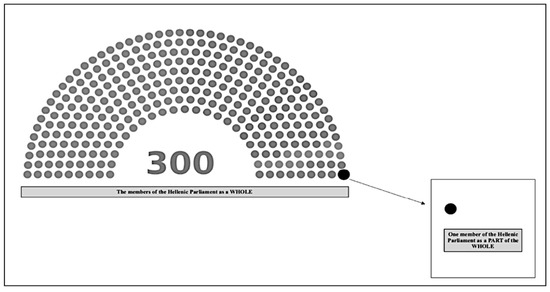

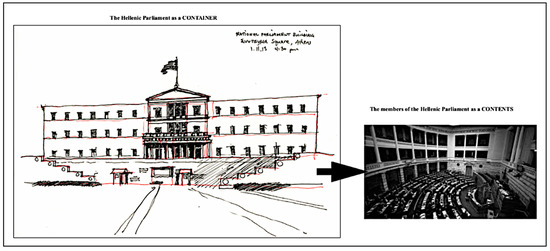

Following Radden and Kövesces’ (2007 [12]) theory regarding the expressivity of metonymic expressions, it is suggested that the deictic adverb εδώ [here], besides its temporal and spatial denotations, encourages the metonymic readings of (i) container for content (The Parliament stands for container and the members of the Parliament stands for contents) and (ii) part-for-whole (see Figure 1) (the member of the Parliament who criticizes the governing political party stands for part and the members of the government stand for whole). It is also suggested that these metonymic readings are rooted to the containment image schema (see Figure 2) because two specific groups of people are indicated (the members of the government and the members of the opposition parties) by serving as entities within a container (the Hellenic Parliament).

Figure 1.

The part for whole image schema communicated by the use of the Greek deictic adverb εδώ [here] in political speeches.

Figure 2.

The containment image schema communicated by the use of the Greek deictic adverb εδώ [here] in political speeches.

Along the same lines, it is argued that, in (2), the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] are used metonymically since they refer to a particular political party (pasok) rather than in purely spatial senses.

2. Εμείς δεν λέμε άλλα εδώ, άλλα εκεί, άλλα μέσα κι άλλα έξω. Γιατί εμείς Πασόκ δεν είμαστε. Λέμε παντού τις απόψεις μας και βρίσκουμε όλο και μεγαλύτερη κατανόηση από τους συνομιλητές μας.

[We do not walk around pronouncing other statements here and other statements there, other statements inside (the Parliament) and other statements (outside of the Parliament). Because we are not pasok. We declare our opinions everywhere and we gain a greater understanding from our interlocutors.]

In (2), the deictics εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] have a metonymic basis because they do not refer only to the statements of the members of the governing party (stated both within the Hellenic Parliament and outside) but also to the members of the governing party. Εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] have a referential metonymic basis because they also refer to the audiences and the members of the governing political party address, namely, the members of the other political parties and the audiences (the citizens) whom they address to declare their political views.

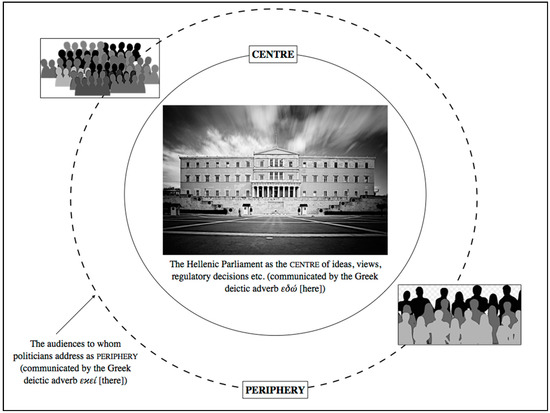

It is also suggested that, in (2), the metonymicity of the deictics εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] is encouraged by the image schemas of containment and center-periphery. As far as the containment image schema is concerned, it is stated that the members of the governing party stand for contents, and the Hellenic Parliament (as a physical space) stands for the container. As far as the center-periphery image schema (see Figure 3) is concerned, it is suggested that εδώ [here] stands for the center (= the Hellenic Parliament where ideas, views, regulatory decisions are voted) and εκεί [there] stands for periphery (= the people to whom politicians address).

Figure 3.

The centre-periphery image schema communicated by the use of the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] in political speeches.

3. The Greek Deictics εδώ [Here] and εκεί [There], Polysemy, and Metonymy

According to Evans (2009; p. 149 [13]), polysemy is the phenomenon whereby “[…] a single vehicle has multiple related sense-units associated with it”. According to Taylor (2003; p. 638 [14]), polysemy deals with the association of two or more related senses with a single linguistic form; hence, polysemy is not only a property of words but also a property of morphemes, morphosyntactic categories, and even syntactic constructions. Moreover, according to Nerlich and Clark (2003; p. 7 [15]), polysemy manifests the way language is employed because language constitutes a system that prompts for conceptual integration. Therefore, linguistic expressions prompt for the evocation of meanings rather than simply representing meanings.

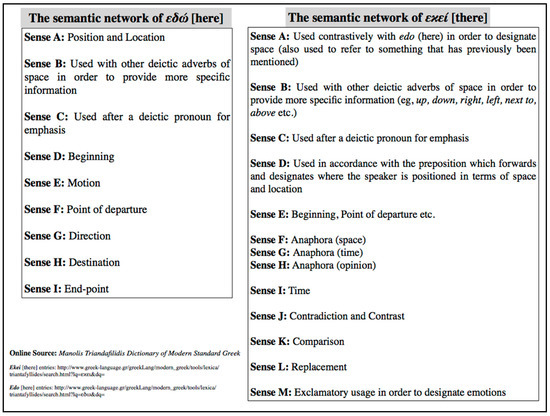

Along the same lines, a review of the literature of polysemy suggests that the abstract meaning of a word can be seen as an instance of a core meaning from multiple senses derived (cf, Tyler and Evans, 2003; Taylor, 2003; Geeraerts, 2010 [14,16,17]). Therefore, new senses can emerge as various extensions from a core meaning. According to these ideas, the new senses can be seen as abstractions because they are the indicators of clusters of other sub-senses. Applying these theories to the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ (here) and εκεί (there), it is suggested that their semantic networks include the core and the prototypical senses of time and space, which are then extended to more abstract and less literal new sub-senses. Figure 4 illustrates the semantic networks of these deictic adverbs (their senses were retrieved from Manolis Triantafyllides Dictionary of Modern Standard Greek [18]).

Figure 4.

The semantic networks of the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there].

Moreover, according to Evans and Green (2006; pp. 270–271 [19]), polysemy networks constitute cluster models of Idealized Cognitive Models (ICMs) and provide a number of different subcategories for a given category. According to them, ICMs (i) include simple elements and connections between them, (ii) represent image schemas, (iii) designate metaphoric and metonymic mappings, (iv) can function symbolically. As Figure 4 illustrates, the senses of time and place are the core meanings of the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there]. In its more abstract senses, εδώ (here) can be used for emphasis (3).

3. Eδώ σου είπα να το βάλεις.

[Here I told you to put it.]

This deictic adverb can be also extended to the sense of directionality by designating the senses of “here”, “there”, “beyond”, “front-back”, “right-left” (4).

4. Έτρεξε κατά δω.

[He run over here.]

As far as motion is concerned, εδώ (here) denotes the location of the speaker in combination with motion (5).

5. Μην φύγετε από δω.

[Don’t go (from here).]

When it comes to the language of politics, it is suggested that, in (6), the core meaning of εδώ (here) is spatio-temporal but extends into more abstract senses.

6. Εδώ και τώρα εκλογές.

[Elections here and now.]

In (6), εδώ [here] is used metonymically because it is employed within a specific context. Εδώ [here] is used in political discourse, which takes place within the Hellenic Parliament, and members of the opposition parties demand the governing party to conduct elections earlier than planned. It is argued that this deictic adverb is used metonymically since it refers both to the socio-political situation of Greece during 2011 and to the individual political actions of the members of the governing party (the governing party is considered to be responsible for the financial situation of Greece according to the accusations of the opposition parties). Therefore, the metonymic reading of activity for related phenomena is encouraged. The political actions of the governing party stand for activities (e.g., political decisions regarding austerity measures and imposition of taxes), and elections stand for related phenomena (the opposition parties disagree with the political decisions of the governing party and they demand elections; elections constitute the consequence or the effect of the governmental policy, which is questioned by the other members of the Hellenic Parliament).

4. Time, Space, and the Greek Deictic Adverbs εδώ [Here] and εκεί [There]

4.1. Temporal Cognition

According to Evans (2007; pp. 733–734 [20]), temporal cognition is one aspect of conceptual structure that relates to our conceptualization of time; unlike space, time is neither a concrete nor a physical sensory experience because temporal experience is both phenomenologically real and subjective. Subjective experience of time is not a single unitary phenomenon; on the contrary, it comprises experiences such as our ability to access and perceive duration, simultaneity, and points of time (ibid; p. 735 [20]). Along the same lines, Hale (1993; pp. 88–89 [21]) defined time as a subjective experience, as the currency of life and the medium through which we find life both meaningful and enjoyable. Gruber, Wagner, Block, and Matthews (2000; p. 50 [22]) claimed that the sooner we process information, the better information we accrue about events. They also suggested that our experience about events will be more subjective.

Moreover, Flaherty (1999; p. 96 [23]) claimed that humans experience time as “protracted duration”, which is triggered by the context of empty and full intervals (intervals that are full of significant events). According to him, “[p]rotracted duration is experienced when the density of conscious information processing is high. The density of conscious information is low when the subject is attending to less of the stimulus array” (ibid; pp. 112–113 [23]). For example, low density is present in cases of expressing routine habitually, and time seems to go by quickly (e.g., every morning I open the window). On the other hand, high density refers to situations where time seems to pass more slowly (e.g., She was waiting for three hours!).

The Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] are broadly used in everyday language. When these deictics express time, they denote either high or low density. However, in political discourse, εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] are used both deictically and emphatically and express high density. This suggestion is based on the fact that political debates use language in a more expressive manner because they are subject to the need of a generalized social and economical change. Therefore, in political discourse, these deictics are used by speakers in order to stress their arguments against the hearers whose political views are idiosyncratically opposite. In (7), the deictic εκεί [there] expresses high density because it refers to a long-term financial situation that is considered to be devastating for cultural, social, and financial development of Greece.

7. Συνήθως λένε ότι η κρίση επιστρέφει εκεί που ξεκίνησε.

[It is often said that the (economic) crisis returns there (= where) it stared.]

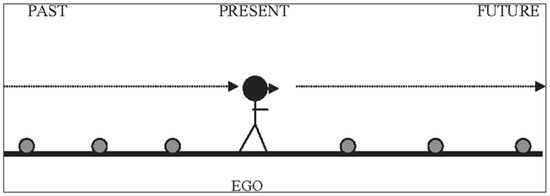

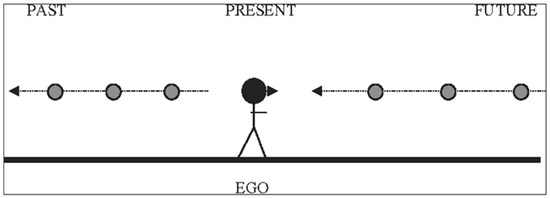

As far as the cognitive models for temporal cognition are concerned, Evans (2007 [20]) argued for the Moving Time Model and the Moving Ego Model. In the Moving Time Model (see Figure 5), the ego’s location correlates with the experience of the present and serves as the reference point for establishing the temporal location of other temporal concepts (ibid; p. 751 [20]). Thus, the ego is located in present time and locates the temporal dimensions of future and past. In the Moving Ego Model (see Figure 6), only the ego moves; time does not move because temporal events constitute locations (ibid; p. 753 [20]).

Figure 5.

The Moving Time Model; reprinted from Evans (2007 [20]).

Figure 6.

The Moving Ego Model; reprinted from Evans (2007 [20]).

As far as these two models for temporal cognition are concerned, it is suggested in (7) that the metonymic readings of the Greek deictic adverb εκεί [there] are encouraged by the Moving Time Model. The speaker locates himself/herself in the present time and makes a reference to the temporal dimensions of past. He/she states that Greece will not only overcome the current economic crisis (= locates himself/herself in the present) but will also return to the past financial situation (= he/she refers to a past temporal location where the economic crisis in Greece has started). Therefore, in (7), the deictic function of εκεί [there] serves to communicate a past financial situation that refers to economic recession, unemployment, bankruptcy, and wrong political judgments and decisions.

4.2. Spatial Cognition

According to Svorou (1993; p. 5 [24]), the spatio-temporal anchoring of our language is not only the basis of our understanding of linguistic messages but also the basis for anticipating certain kinds of linguistic messages. We locate entities and situations spatially, and each of these expressions carries a different degree of explicitness in the encoding referents of the world. Explicitness incorporates the weighted relevance of various conceived elements of the situation with respect to the communicative intent of the speaker (ibid; p. 6 [24]). With regard to the degree of explicitness, it is observed that εδώ [here] has the lowest degree of explicitness because the speaker simply considers knowledge of his/her position as adequate information for the listener to locate the entity under question. Hence, speakers act as reference points not only in terms of time but also of space.

Applying these ideas to the way the Greek deictic adverb εδώ [here] is used in political speeches, it is suggested that εδώ [here] positions speakers as reference points of situations and temporal aspects (which are rooted to both time and space) (8).

8. Oλοκληρώνοντας την εισαγωγή της, η κ. X υπογράμμισε ότι όλα τα ανωτέρω αποκτούν εδώ νόημα στο πλαίσιο μιας συνολικής αλλαγής του οικονομικού μοντέλου, σύμφωνα με τις θέσεις που έχει εκφράσει ο Πρωθυπουργός και Πρόεδρος του πασοκ, και η Oμάδα των Σοσιαλιστών και Δημοκρατών.

[After finishing her introduction, Mrs. X has underlined that all the above mentioned make sense here, within the framework of an overall change of the economic model, in accordance with the statements that have been expressed by the Prime Minister and president of pasok and the group of Socialists and Democrats.]

In (8), εδώ [here] locates the speaker in time and place (the Hellenic parliament). Τhe speaker serves as the reference point of a spatio-temporal anchoring. The metonymic readings of the deictic adverb εδώ [here] are licensed by the image schemas of containment (the members of the parliament stand for contents, and the Hellenic Parliament, as an instance of physical space, stands for container) and linkage-separation (the speaker refers to a specific group of people, namely, the Prime Minister and the members of his party (= linkage) rather than to the members of every political party of the Hellenic Parliament (= separation)).

4.3. Time is Space

Langacker (1986 [25]; 1988 [26]) and Talmy (2007 [27]) observed that the way in which we locate objects with regard to one another involves the recognition of some kind of asymmetrical relation between the object we want to locate and the object with respect to where we locate it. According to them, asymmetrical relations are recognized on the basis of size, containment, support, orientation, order, direction, distance, motion, or a combination of these. Svorou (1993 [24]) stated that a spatial arrangement of two entities could be described in a number of ways, each of which constitutes a construal.

Radden and Dirven (2007; p. 304 [28]) suggested that time could not be separated from space. They argued for physical space by referring to absolute reference frames and relative frames (physical space and objects are relatively specified to one or more reference object). Their approach to spatial cognition stated that the property of extent is very important due to the existence of a relation between a thing and its measured property (ibid; p. 307 [28]). According to them, extent could be a static relation (length), a dynamic relation (distance covered in motion), or even a static relation that could be viewed as dynamic (distance in fictive motion) (ibid; p. 307 [28]).

With respect to the aforementioned ideas, it is suggested that, in (9), the property of extent subjects to the metonymicity of the Greek deictic adverb εδώ [here].

9. Πώς φτάσαμε ως εδώ; H Κυβέρνηση Καραμανλή, που ακολούθησε, συνέχισε τις σπατάλες και την [πολιτική] αδιαφάνεια, δεν πήρε τα μέτρα που έπρεπε να πάρει εγκαίρως και σήμερα ο Γιώργος Παπανδρέου τρέχει και δεν φτάνει. Aμαρτίες γονέων παιδεύουσι τέκνα.

[How did we come to this (= here)? Karamanlis’ government, which followed, continued the financial extravagances and the (political) non-transparency, did not take the measures they should take early enough and today Giorgos Papandreou is in a tearing hurry. The sins of the fathers are visited upon the children.]

In (9), extent is illustrated as a static relation that becomes dynamic. Εδώ [here] has both a spatial and a temporal value because it describes the length and the duration of the economic situation of Greece. As far as time and space are concerned, εδώ [here] functions as the reference point of the economic crisis. In (9), the deictic adverb designates the concept of time as both a subjective and an objective experience. The concept of time can be viewed as subjective if we consider how the speaker experiences the socio-political crisis on the basis of individual parameters and viewpoints. Time can be also seen as objective if we consider the actual time the utterance was pronounced. As far as space is concerned, it is suggested that, in (9), the deictic adverb εδώ [here] refers both to physical and abstract space. The Hellenic Parliament stands for physical space, whereas Greece indicates a more abstract dimension of space.

5. How the Greek Deictics εδώ [Here] and εκεί [There] Construct Spatial Scenes

According to Talmy (2007 [27]), there are two sub-systems that can be used for the conceptualization of spatial cognition. On the one hand, the first sub-system includes all the schematic delineations that can be conceptualized as existing in any volume of space; hence, it could be treated as a matrix or a framework that contains and localizes spatial aspects (ibid; p. 769 [27]). In this sub-system, static concepts include region and location, whereas dynamic concepts include path and placement. On the other hand, the second sub-system consists of the configurations of interrelationships of material occupying a volume of the first subsystem. Thus, it has more contents of space: (i) an object is a portion of material and is conceptualized as having a boundary around it (as an intrinsic aspect of its identity and makeup, and (ii) a mass has no boundaries (ibid; p. 769 [27]).

A spatial scene is constructed under the spatial disposition of a focal object. According to Talmy (2007; p. 770 [27]), such a disposition “[…] is largely characterized in terms of a single further object, also selected within the scene, whose location and geometric properties are already known and function as a reference object”. The site, path, and orientation of the first object is indicated in terms of distance from or in relation to the geometry of the second object (ibid; p. 770 [27]).

In (10), there is a strong contrast between the deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there]. This kind of contrast is manifested by their metonymic readings and especially by the image schemas of splitting and removal.

10. Εμείς είμαστε εδώ και θα παραμείνουμε εδώ, ενώ εσείς είστε και θα παραμείνετε εκεί, μακριά από τα προβλήματα και την πραγματικότητα.

[We are here and we will stay here, whereas you are and you will remain there, far from the problems and reality.]

It is also suggested that, in (10), the meaning of the Greek deictic adverb εκεί [there] is very close to the semantics of away from. As Talmy (2007; p. 771 [27]) highlighted, away from indicates the motion of a schematic “Figure” along a path that progressively increases its distance from a schematically point-like “Ground”. In (10), the notion of “Figure” is indicated by the members of the opposition political parties. According to the speaker, their political views and ideas are irrelevant to reality (= path). Moreover, in (10), the speaker is a member of the governing political party who criticizes the idiosyncrasy of the opposition parties and states that their political stance has nothing to do with the way they should act inside the Hellenic parliament (= “Ground”).

With respect to the aforementioned ideas concerning the construction of a spatial scene, Svorou (1993 [24]) argued for three ways in which reference objects localize figures. The first way is guide-based because the speaker can function as an external punctual object, often with special locations for the situation. For instance, in (11), the speaker uses the deictic adverb εδώ [here] emphatically in order to highlight a problematic financial situation both in terms of time (2011 was the year these political speeches took place) and space (Hellenic Parliament as physical space and Greece in general as a more generic and abstract space).

11. H κρίση κύριοι ειναι εδώ, στην καρδιά της Ελληνικής οικονομίας.

[Ladies and gentlemen the crisis is here, within the heart of Greek economy.]

In addition, Svorou (1993 [24]) stated that the second way in which reference objects localize figures is non-projective. According to her, the external object lacks either an asymmetric geometry or, if it has one, its projection is not being used for a localizing function. In (12), the speaker does not serve as the reference point because he/she refers to an external object. Assuming that the deictic adverb εκεί [there] has a metonymic reading, it is stated that εκεί [there] does not simply locate the object (Samaras) in physical space (Omonia). The object communicates an asymmetric relation between the speaker of the utterance (a member of Samaras’ political party, which was the largest opposition party during 2011) and the members of the governing party. Therefore, the metonymicity of εκεί [there] is encouraged by the image schemas of splitting and removal, which indicate the contrast between the actions of the governing political party and the actions of the dominant opposition party.

12. O Σαμαράς πήγε εκεί, στο κέντρο της Aθήνας, στην Oμόνοια για να συζητήσει με τους μετανάστες.

[Samaras went there, in the centre of Athens, in Omonia in order to speak to the immigrants.]

According to Svorou (1993 [24]), the third way in which reference objects localize figures indicates that an external secondary reference object can have an asymmetric geometry that projects out from it to form a reference frame. This means that either the speaker or some previously established viewpoint can serve as the source of the projection. For example, in (13), the speaker refers to an external reference object (all the above-mentioned make sense here) that has been projected previously.

13. Oλοκληρώνοντας την εισαγωγή της, η κ. X υπογράμμισε ότι όλα τα ανωτέρω αποκτούν εδώ νόημα στο πλαίσιο μιας συνολικής αλλαγής του οικονομικού μοντέλου.

[After finishing her introduction, Mrs. X has underlined that all the above mentioned make sense here, within the framework of an overall change of the economic model.]

6. Conclusions

This paper examined the way the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] are used in political discourse. The examples analyzed were drawn by political speeches that took place in the Hellenic Parliament during 2011. These political speeches dealt with the socio-political and the economic crisis Greece was confronting during that time. The linguistic examples showed that the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] designate time and space both in physical and in abstract senses. It was suggested that the metonymicity of these deictics is rooted to image schemas, namely, containment, part-for-whole, centre-periphery, removal, splitting, and linkage-separation. It was also argued that image schemas play a crucial role in understanding how the Greek deictic adverbs εδώ [here] and εκεί [there] function in political discourse because image schemas embody visual, auditory, and kinesthetic aspects of how we think, reason, and construct speech.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Chomsky, N.; Otero, C.P. Language and Politics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, A. The Language of Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, N. Brewer’s Politics: A Phrase and Fable Dictionary, revised edition; Cassell PLC: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- O’Barr, W. (Ed.) Politics Affecting Language. In Language and Politics; Mouton: Hague, The Netherlands; Paris, France, 1976; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R. Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes in Linguistic Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Panther, K.U.; Radden, G. (Eds.) Introduction. In Metonymy in Language and Thought; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, R.W. Reference-point Constructions. Cogn. Linguist. 1993, 4, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, R.W. Metonymic Grammar. In Metonymy and Metaphor in Grammar; Panther, K., Thornburg, L., Barcelona, A., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Conceptual Metaphor in Everyday Language. J. Philos. 1989, 77, 453–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirven, R. Metonymy and Metaphor: Different Mental Strategies of Conceptualization. In Metaphor and Metonymy in Comparison and Contrast; Dirven, R., Pörings, R., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 75–111. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, W. The Darwinization of Linguistics. Selection 2002, 3, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radden, G.; Kövesces, Z. Towards a Theory of Metonymy. In The Cognitive Linguistics Reader; Evans, V., Bergen, B., Zinken, J., Eds.; Equinox Publishing Ltd.: London, UK; Oakville, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 335–359. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, V. How Words Mean: Lexical Concepts, Cognitive Models, and Meaning Construction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R. Polysemy’s Paradoxes. Lang. Sci. 2003, 25, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, B.; Clarke, D. (Eds.) Polysemy and Flexibility: Introduction and Overview. In Polysemy: Flexible Patterns of Meaning in Mind and Language; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, A.; Evans, V. The Semantics of English Prepositions: Spatial Scenes, Embodied Meaning and Cognition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts, D. Theories of Lexical Semantics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Manolis Triantafyllides Dictionary of Modern Standard Greek. Available online: http://www.greek-language.gr/greekLang/modern_greek/tools/lexica/triantafyllides/ (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Evans, V.; Green, M. Cognitive Linguistics: An Introduction; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, V. (Ed.) How We Conceptualize Time: Language, Meaning and Temporal Cognition. In The Cognitive Linguistics Reader; Equinox Publishing Ltd.: London, UK; Oakville, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 733–765. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, C. Time Dimensions and the Subjective Experience of Time. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1993, 33, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, R.; Wagner, L.; Block, R.; Matthews, S. (Eds.) Subjective Time vs. Proper (Clock) Time. In Studies on the Structure of Time; Kluwer Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, M. A Watched Pot: How We Experience Time; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Svorou, S. The Grammar of Space; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, R.W. An Introduction to Cognitive Grammar. Cognit. Sci. 1986, 10, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, R.W. Nouns and Verbs. Language 1988, 63, 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy, L. How Language Structures Space. In The Cognitive Linguistics Reader; Evans, V., Bergen, B., Zinken, J., Eds.; Equinox Publishing Ltd.: London, UK; Oakville, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 766–830. [Google Scholar]

- Radden, G.; Dirven, R. Cognitive English Grammar; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).