Abstract

Despite the ubiquitous application of gamification in livestreaming commerce, the mechanisms driving its impact on consumer participation remain underexplored. To address this research gap, this study integrated two theoretical frameworks: the “Gamification Affordances–Psychological Outcomes–Behavioral Outcomes” framework and the Uses and Gratifications Theory. We investigated how gamification affordances (achievement visualization, rewards, interaction, and competition) relate to the fulfillment of consumers’ diverse psychological needs (cognitive, affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative). Furthermore, we examined whether meeting these psychological needs influences consumers’ intentions to continue watching and to purchase. We surveyed 354 livestreaming commerce consumers and employed structural equation modeling to analyze the data. The findings revealed that gamification affordances can motivate consumers’ continuous watching and purchasing behavior by satisfying their different psychological needs. We conclude by discussing the theoretical and managerial implications of our findings.

1. Introduction

As an increasingly popular business model, livestreaming commerce integrates livestreaming with e-commerce, directly connecting brand companies with consumers and instigating trust and engagement [1,2]. Eliminating intermediate parties significantly reduces transaction costs and enhances marketing efficiency. In China, for instance, by the end of 2024, there were 1.108 billion internet users (The 55th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development, retrieved from https://source.ckcloud.busionline.com/2025-01-21_678f1454516fe.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2025)), with 597 million actively engaging in livestreaming commerce (The Number of Livestreaming Commerce Users in China reached 597 million, accounting for 54.7% of the total number of netizens, retrieved from https://www.163.com/dy/article/JEAM42LD05199LJK.html (accessed on 16 February 2025)). The overall market scale of livestreaming commerce in China surpassed CNY 5.8 trillion in 2024 (High-quality Development Report of Livestreaming Commerce Industry: GMV of Livestreaming Commerce Reached 5.86 trillion CNY in 2024, retrieved from https://caifuhao.eastmoney.com/news/20241223223557001630980 (accessed on 16 February 2025)). To sustain consumer participation and differentiate from competitors, livestreaming commerce platforms have turned to gamification, a proven effective mechanism in the marketing context [3]. By introducing gamified artifacts such as intimacy points, fan levels, fan privileges, gifting, lottery, quest rewards, and fan clubs, livestreaming aims to attract and retain consumers, stimulating their purchase intentions [4].

Despite its widespread adoption in livestreaming commerce, the underlying influencing paths of gamification on consumer participation in this context remain unclear. In the context of traditional e-commerce, early research on the effectiveness of gamification on consumer behaviors is abundant [5], but the findings are inconsistent. Some studies have discovered benign effects of gamification on word of mouth, brand loyalty, and resistance to negative information [6,7], while others have pointed out a weak correlation between gamification experience and brand sales [8] and even insignificant effects of certain gamification elements (e.g., badges) on enhancing consumer usage and purchase intentions [9]. Given these inconsistent findings surrounding gamification, recent researchers have suggested analyzing its impact through the lens of affordance [10]. Affordance, in this context, refers to “the action possibilities afforded by the elements and features of gamified systems” [11]. According to the “Need–Affordance–Feature” framework [12], specific gamification elements offer different affordances, catering to consumers’ diverse psychological needs and influencing their behaviors in specific contexts. For example, leaderboards can serve as a means for social comparison or personal goal setting and performance tracking, depending on individual perception. Thus, the consideration of gamification affordance provides deeper insights into consumer motivations and enables more accurate behavior predictions than focusing on gamification elements alone [10].

Although the effect paths of gamification affordances on consumer behaviors in traditional e-commerce scenarios have been comprehensively identified in recent years [11,13], research in the livestreaming commerce context remains scant. A few existing studies have focused on the “element” perspective and examined the effects of specific gamification elements on consumer behaviors in livestreaming commerce [14,15,16,17]. However, none of these studies have adopted the affordance lens and tried to identify the gamification affordances in livestreaming commerce. Without comprehensive knowledge of the gamification affordances enabled by various game elements, it is difficult for designers to tailor the gamified elements to consumers’ psychological needs in livestreaming commerce.

Past research has acknowledged psychological outcomes as indispensable mediators in the influence of gamification affordance on consumer behavior, proposing the widely accepted linkage of “Gamification Affordances–Psychological Outcomes–Behavioral Outcomes” [18]. Following this framework, subsequent scholars have delved into the understanding of the impacts of various gamified affordances on individuals’ psychological reactions and resulting behaviors [11,19]. In the context of mobile apps, Zhou et al. [20] found that affordances such as achievement, reward, playfulness, and competition can promote environmentally friendly behaviors among users, mediated by harmonious and obsessive passions. Similarly, in the context of mobile payments, Zhang et al. [21] confirmed that user retention can be effectively induced by gamification affordances via the mediation of user engagement. However, in the context of livestreaming commerce, no study has yet systematically and comprehensively explored the psychological outcomes associated with gamification affordances and consumer behaviors. Such a research gap poses challenges for livestreaming commerce platform operators in realizing the full potential of gamification design.

The Uses and Gratifications Theory has been realized as an effective theoretical lens to unravel the psychological antecedents of consumer behaviors [22,23]. This theory proposes five psychological needs (cognitive, affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative) that derive from the use of media. This theory has been utilized to explain the psychological needs of individuals when they use various design artifacts of different information systems, such as e-commerce platforms [24], social media platforms [25,26], and virtual worlds [27]. Recently, this theory has also been introduced to explain the psychological antecedents for consumer engagement in livestreaming commerce [22,23]. However, how the psychological needs of consumers are fulfilled by the design artifacts of the livestreaming commerce platforms is still unknown. Therefore, the current study combines gamification with the Uses and Gratifications Theory to examine the effects of gamification design on consumer participation from the angle of psychological needs satisfaction. It can enrich the gamification literature through the identification of a holistic and comprehensive set of psychological mechanisms for gamification effects. A handful of studies have tried to explain the gamification effects with the Uses and Gratifications Theory in online learning and traditional e-commerce contexts [28,29,30]. The current study extends this research to the new context of livestreaming commerce, contributing to this research stream.

In summary, this study strives to provide an accurate response to the question of how gamification affordances in livestreaming commerce shape consumer behaviors by catering to their diverse psychological needs. By empirically exploring the mechanisms at play, this research enhances the theoretical comprehension of gamification effects in the livestreaming commerce context and imparts practical wisdom to designers and operators of livestreaming commerce platforms.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Participation Behaviors in Livestreaming Commerce

The proliferation of online e-commerce platforms is closely linked to the diverse participation behavior of consumers, reflecting their support and, consequently, impacting sales [31]. Consumer participation behaviors in the online sphere can be broadly categorized into transactional, such as purchasing, and non-transactional, including activities like browsing, reviewing, or liking/following [32].

Livestreaming commerce, also referred to as live commerce [33], denotes an e-commerce service where sellers demonstrate products, respond to consumer questions, and offer personalized recommendations through livestreaming while consumers can place orders within the same system [34]. In livestreaming commerce, consumer participation behaviors can also be classified into transactional and non-transactional ones. Behaviors identified in traditional e-commerce also apply here, especially purchasing as a transactional one and continuous watching as a non-transactional one. The latter is pivotal in drawing viewer traffic and facilitating transactions, aligning with the ultimate goal of livestreaming commerce: promoting sales [35].

Prior scholarly efforts have dug into the antecedents for consumer participation in livestreaming, exploring factors like situational, streamer characteristics, and product characteristics. For example, Chen et al. [36] uncovered that product quality, streamers’ knowledge level, endorsements, and streamer–consumer value similarity influence purchase intentions and intensity through trust. Similarly, Gao et al. [37] discovered that complete and up-to-date product information, streamer trustworthiness, and co-viewer involvement affect purchase and response intentions via perceived persuasiveness. Moreover, Kang et al. [32] revealed that real-time interaction impacts non-transactional behaviors via tie strength. Gu et al. [38] pinpointed that the interactivity, newness, vividness, information richness, and social presence of livestreaming foster participation.

Despite extensive research, the impact of gamification in livestreaming commerce remains underexplored. Gamification, with elements like intimacy points, fan privileges, lotteries, quest rewards, and fan clubs, is increasingly used by livestreaming platforms to enhance participation. However, its precise effects on consumer behaviors and the underlying mechanisms are unclear. Chang and Yu [14] showed that gamification elements, including reward and competition, can enhance customers’ sense of presence and immersion, which further fosters their purchase intentions. Similarly, Fayola et al. [15] found that achievement- and social-based gamification elements can affect consumers’ sense of presence, immersion, and intent to purchase. In addition, Yu et al. [17] discovered that gamification can induce impulsive consumption via social innovativeness in gastronomy livestreaming. Nguyen-Viet and Nguyen [16] also confirmed that gamification enhances impulse-buying intentions through swift guanxi in live commerce. As evidenced by these findings, the current findings on the effects of gamification on consumer participation remain scarce and scattered. The few existing studies focused on transactional behaviors such as purchases, ignoring non-transactional ones, which are of paramount importance to livestreaming sellers. Hence, a holistic examination of gamification effects on both transactional and non-transactional participation behaviors in livestreaming commerce is crucial for maximizing the value of gamification design in this context.

2.2. Gamification and Gamification Affordance

Gamification, a potent tool, motivates users to engage in desirable behaviors by introducing gamification elements and mechanisms, aiming to stimulate their interest in using (or purchasing more products) through the introduction of gamification elements and mechanisms [5]. Huotari and Hamari [39] argued that integrating gamified experiences into products or services can enhance merchants’ appeal. Marketing literature consistently demonstrates that a gamified experience boosts customer engagement, loyalty, purchase intentions, and other key behaviors. This, in turn, fosters a more positive attitude toward products or services and drives increased purchases [40]. Recognizing gamification’s potential, livestreaming commerce platforms are employing game mechanics to activate and sustain customer participation.

The effectiveness of gamified marketing relies on systematic and meaningful design, incorporating elements such as points, badges/medals, leaderboards, gifts, tokens, personalization, levels/ranks, experience bars, and teams [41]. However, research findings on gamification’s marketing impact are mixed. For instance, Harwood and Garry [42] found that challenges and rewards enhance consumer engagement, leading to increased trust, commitment, and brand interaction. Conversely, Gatautis et al. [8] observed that consumers do not always associate gamified experiences with specific brands, resulting in low brand engagement. Additionally, Mavletova [43] noted a higher non-response rate in gamified survey questionnaires compared to standard ones. Some studies have also failed to identify the significant effects of gamification on consumer participation (e.g., [9]).

To reconcile these conflicting results, recent studies have examined gamification effects through the lens of affordance [11]. Affordances, referring to actionable traits enabled to an actor by an object [44], influence individual psychology and behavior more than technical features [12,45]. Gamification affordances are action possibilities furnished by game artifacts and mechanics [11], more accurately predicting consumer behaviors than technique features alone [10]. For example, leaderboards can be perceived as tools for competition or goal-setting, shaping individual appraisals, usage patterns, and behaviors. Understanding gamification affordances (i.e., consumer perception) is crucial for successful gamification implementation [10].

Identifying these affordances requires considering research subjects and application scenarios [46]. Previous studies have identified various gamification affordances in different contexts (see Table 1). Suh and Wagner [10] studied an internal knowledge management system, finding that achievement visibility, rewardability, and competition influence employee contributions. In e-commerce, MiniApps, four affordances—autonomy support, self-expression, interactivity, and competition—have been found to drive consumer citizenship behavior through psychological ownership [11]. Other studies on mobile payment platforms and pro-environmental behaviors have revealed that rewards, feedback, competition, and cooperation can strongly engage and retain customers [20,21]. More recently, rewardability, competition, and achievement visibility have also been identified as factors that promote customer social capital accumulation [47].

Table 1.

Summary of studies identifying gamification affordances.

In the livestreaming commerce literature, existing studies have focused on specific gamification elements rather than the affordances they enable [14,15,16,17]. No study has yet systematically explored the dimensions of gamification affordances in livestreaming commerce platforms. In such a context, increased intimacy points and fan level visualize consumer achievements, realizing the affordance of achievement visualization. Rewards are perceived through intimacy points, fans’ privileges, and monetary compensations for task completion. Consumers frequently interact with streamers and peers during livestream shopping, enabling the affordance of interaction. Competition arises as consumers from different fan clubs vote and gift their favorite streamers. Therefore, the current study focuses on four prominent gamification affordances in livestreaming commerce: achievement visualization, rewards, interaction, and competition.

Regarding the effect of gamification affordance on consumer behaviors, past research aligns with the framework of “Gamification Affordances–Psychological Outcomes–Behavioral Outcomes” [46]. For instance, Huang and Zhou [48] identified the paradoxical effects of social gamified affordances on the usage of pro-environmental IT services via recognition and social overload. Chen et al. [49] found benign impacts of gamification affordances on user value perceptions and environmental contributions. In e-commerce, psychological outcomes like engagement and psychological ownership can explain the driving forces of gamification affordances on purchasing and citizenship behaviors of consumers [11,21]. However, research exploring the psychological outcomes that channel the impact of gamification affordances toward customer behaviors in livestreaming e-commerce remains scarce.

2.3. Uses and Gratifications Theory

The Uses and Gratifications (U&G) theory, which originated in communication studies, has received widespread attention from experts in the field of Information Systems. This theory interprets the psychological and behavioral impacts of mass communication by considering the motives for media use from the audience’s perspective. Since the 1940s, scholars have explored the reasons why users choose different media, discovering diverse purposes for engaging with the same media. For instance, during the New York newspaper strike, individuals read newspapers for various reasons, such as information, pleasure, or habit.

Katz summarized people’s need to access media into five categories: cognitive needs (acquire knowledge and information), emotional needs (pursue enjoyment and pleasure), personal integration needs (express oneself and improve social status, credibility, and ability), social integration needs (expect social interaction, obtain identity, and abide by subjective norms), and pressure release needs (escape reality and divert attention temporarily) [50]. However, subsequent studies applying the U&G theory have not strictly adhered to Katz et al.’s [50] categorization, instead focusing on identifying distinct needs in specific contexts.

The U&G theory posits that users utilize media and technology with individual needs or motivations and long for satisfaction from such usage. If their personal expectations are met, they are inclined to continue their usage [51]. In the online context, users’ media usage behavior is more complex, and research on the U&G theory has been enriched by changing research scenarios. Recently, the theory has been applied to explain user behaviors on online shopping and livestreaming platforms. For example, Kaur et al. [26] developed a holistic research model grounded in the U&G theory, concluding that the cognitive needs, social avoidance needs, entertaining needs, and social sharing needs of mobile instant messaging users impact their continued use and purchase behavior. Hou et al. [52] constructed and tested models of influencing factors for users’ willingness to continue watching and purchasing on a Chinese livestreaming platform (Douyu Platform), employing mixed qualitative and quantitative methods focused on entertainment and social needs. However, research adopting the U&G theory to explain customer consumption behaviors in livestreaming e-commerce remains limited.

Past studies have built on the U&G theory and found that gamification design elements enhance user participation by satisfying different psychological needs [28,29,30]. Similarly, in the specific scenario of livestreaming e-commerce, gamified elements, and functions can stimulate and satisfy various psychological needs of customers through various dimensions of gamification affordances. The satisfaction of these psychological needs, in turn, drives customers’ participation behaviors [22,23]. Thus, the U&G theory stands as a strong theoretical foundation for unraveling the effect paths of gamification on consumer behaviors in such a context. Combining gamification with the Uses and Gratifications Theory to examine the effects of gamification design on consumer participation in livestreaming can contribute to both gamification and the U&G theory in the context of livestreaming commerce.

Surveying the current scholarly landscape on livestreaming commerce, we postulate that customers have cognitive, affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative needs when engaging in live shopping. The cognitive need is defined as the desire to understand and rationalize the empirical world. Individuals have varying needs for cognitive situational information when facing the same situation. Katz [53] believed that individuals possess a need for understanding, and cognitive needs are shaped by whether information sources meet this need. In marketing scenarios, cognitive needs significantly impact individual psychology and behavior [54]. When consumers participate in live shopping, they often seek detailed and authentic knowledge about products, which can be competently satisfied through streamers’ presentations and introductions.

The affective need is a need for emotional or spiritual fulfillment. As living standards improve, people increasingly seek enjoyment, pleasure, and other emotional experiences while shopping. The positive emotional interaction between consumers and live streamers fosters positive emotions and enhances affective satisfaction. Social needs are fundamental, as individuals strive to engage in various social relationships in their daily lives [55]. In livestreaming commerce, the convenience of synchronized interaction enables consumers to connect with streamers or other consumers, establishing social bonds and fulfilling their social needs.

Personal integrative needs serve as a reference for individuals to gain self-assessment, encompassing desires for self-expression and the enhancement of confidence and status. In consumption, particularly in livestreaming e-commerce, these needs motivate consumers to select products and services that align with their values, tastes, and aspirations. By purchasing items that reflect their personality and preferences, consumers achieve self-expression. Additionally, live streamers’ detailed product explanations ensure customers have a comprehensive understanding, thereby boosting their shopping confidence. Consequently, livestreaming e-commerce effectively satisfies consumers’ personal integrative needs.

Social integrative needs have an inherent environmental monitoring function. Individuals have a natural desire to belong to specific groups, seeking clear personal or social identities within different communities. These identities signify recognition as a member of a particular group, leading individuals to adhere to group norms. In the live shopping scene, consumers can join various fan clubs associated with anchors or brands, developing a sense of belonging through interacting with streamers and peers. As they watch and purchase more from a specific brand or celebrity’s livestream, their fan level increases, along with a stronger sense of identity.

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

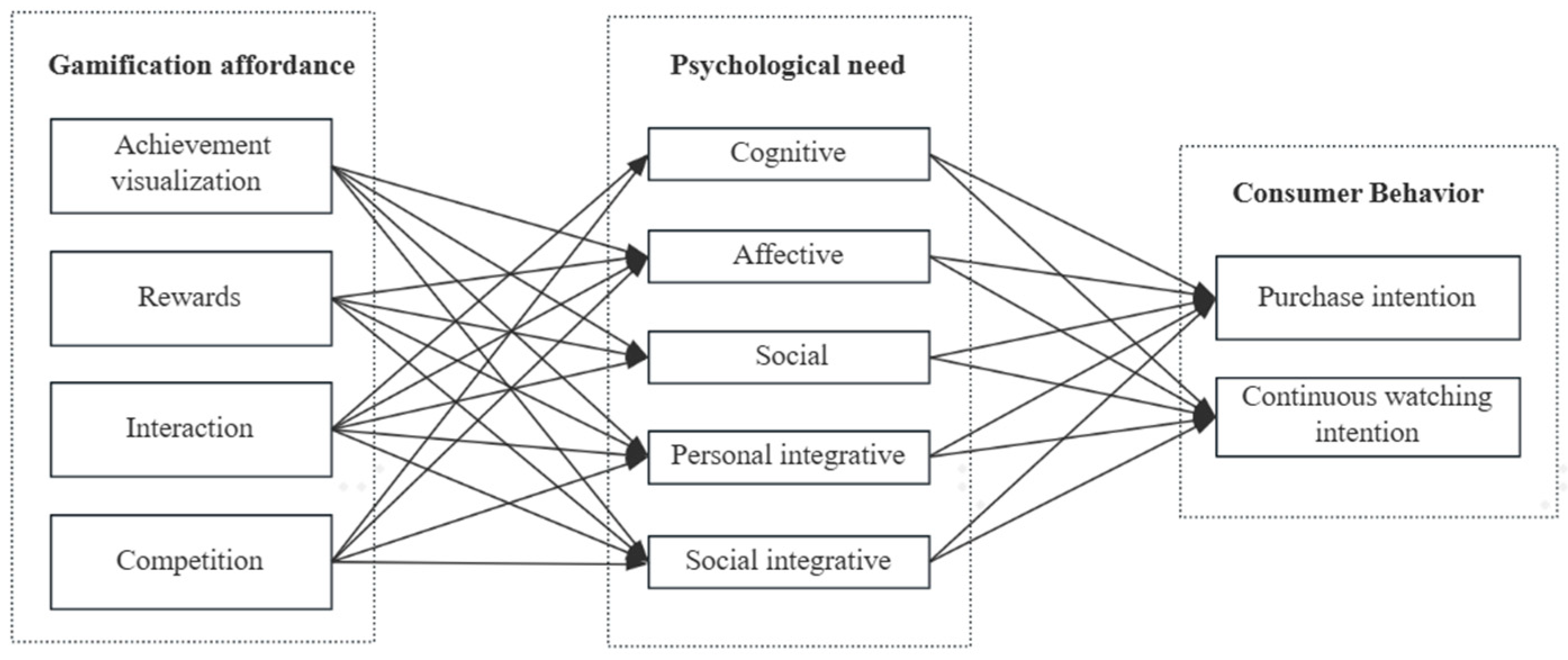

Grounded on the recognized framework of “Gamification Affordances–Psychological Outcomes–Behavioral Outcomes”, we developed a research model to investigate the effect of gamification affordances on consumer participation behaviors in the realm of livestreaming commerce (Figure 1). Additionally, we put forward the following hypotheses to test the relationship among gamification affordances, the fulfillment of psychological needs, and consumer participation behaviors.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.1. The Effect of Gamification Affordances on Psychological Needs

Achievement visualization affordance refers to the affordance that enables users to display their accomplishments in gamified systems through ranks, badges, and virtual trophies. Prior research has shown its positive impact on organizational members [56]. Similarly, in the livestreaming environment, visualizing users’ achievements encourages consumers to strive for higher scores and achievements. When consumers interact with gamification artifacts and mechanics in e-commerce livestreaming, they can see their accomplishments and contributions, fostering positive emotional experiences such as satisfaction and a sense of achievement [57].

Achievement visualization affordance is not merely an indicator of individual success; it also drives social interaction [47]. It motivates consumers to engage in citizenship behaviors and build relational capital, fulfilling their social needs [47]. High-achieving consumers are driven by the need to demonstrate their status, while those with lower achievements are inspired by witnessing recognition of citizenship behaviors. Frequent citizenship behaviors enhance social interactions, satisfying consumers’ social needs. Believing their achievements are visible, consumers are motivated to interact more frequently, showcasing their status and receiving recognition.

Moreover, consumers’ achievements in gamified marketing activities reflect their ability or knowledge level improvements and meet their status enhancement needs through visualized leaderboards and levels [10]. In livestreaming e-commerce, personal integrative needs involve consumers’ pursuit of self-shopping ability and identity recognition. Achievement visualization features reinforce their self-identity and self-worth by showcasing consumers’ shopping abilities and achievements (e.g., premium membership status and exclusive discounts). These achievements recognize past shopping behaviors and motivate future ones, helping consumers establish a positive self-image.

This achievement visualization fosters a strong sense of social identity [58]. Achievements like badges and fan levels serve as recognition of past behaviors and motivators for future ones, enhancing consumers’ positive image. In this process, social recognition, crucial for individual respect and value realization in society, is fulfilled through achievement visualization [59]. According to Social Identity Theory, individuals gain their own identity and self-esteem by categorizing themselves into specific social groups [60]. When consumers receive praise and respect from their peers, they perceive this positive feedback as recognition and acceptance within the community. Consequently, their social identity is enhanced, fostering a strong sense of belonging to this particular social community. With this heightened social identity, consumers become more attentive to and compliant with the social norms and values of the community, thereby fulfilling their needs for social integration [61]. It is thus postulated that achievement visualization affordance can effectively induce and satisfy consumers’ social integrative needs.

Nevertheless, achievement visualization affordance primarily focuses on individual achievements and does not aid in product information understanding, hence not affecting cognitive needs.

Based on the above discussion, we believe that achievement visualization affordance is positively related to consumers’ affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative needs. Thus, we propose H1a–d.

H1a.

Achievement visualization affordance is positively associated with affective needs.

H1b.

Achievement visualization affordance is positively associated with social needs.

H1c.

Achievement visualization affordance is positively associated with personal integrative needs.

H1d.

Achievement visualization affordance is positively associated with social integrative needs.

Rewards affordance enables consumers to earn various non-monetary rewards (e.g., points, badges, and trophies) or monetary incentives (e.g., coupons and gifts) by completing gamified tasks. Rewards, be they tangible or intangible, can influence users’ affective states [62]. As consumers acquire rewards while watching and purchasing, they experience pleasure and enjoyment, fulfilling their affective needs.

Motivated by the expectation of obtaining more rewards, consumers actively engage in live rooms, sharing their shopping experience, commenting on products, or assisting others with product selections. These positive actions and contributions are customer citizenship behaviors, which in turn reinforce consumers’ social needs by fostering social interactions and nurturing social capital within the community [47].

Moreover, as consumers accumulate rewards through participation in livestreaming commerce, they gain assurance of continuous enhancement in their skills, knowledge, and status. Prior research has shown that the quantity of rewards received is positively correlated with users’ perceptions of self-efficacy and competence enhancement [63,64]. Consequently, the accumulation of rewards in livestreaming e-commerce leads consumers to believe that their shopping skills and knowledge levels are strengthened. This augmentation in capabilities elevates their status within the platform, reflecting their increased contributions and value. Hence, we posit that rewards affordance can strengthen and fulfill consumers’ personal integrative needs, such as personal growth, self-actualization, and self-worth.

Meanwhile, consumers’ eagerness to attain rewards prompts them to interact and contribute to brands and celebrities [2]. Earning more rewards motivates consumers to engage in more live activities, share live rooms, and invite friends, thereby deepening their relationships with livestreaming brands and enhancing their sense of belonging [65]. The rewards system also conveys to consumers that their suggestions and opinions are recognized and valued, which reinforces their sense of belonging [64]. Moreover, livestreaming e-commerce platforms leverage rewards to create a shopping community of consumers with similar interests and goals [2]. Within this community, consumers can learn from each other, share experiences, and fulfill their social integrative needs. The camaraderie and shared purpose fostered by the platform strengthen consumers’ emotional ties to the brand and the community.

However, the rewards only affirm the consumer’s behavior and do not drive the consumer to obtain additional information. Thus, reward affordance is not associated with cognitive needs fulfillment.

Taken together, we believe that the rewards affordance in livestreaming commerce platforms positively impact consumers’ affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative needs. Thus, we propose H2a–d.

H2a.

Rewards affordance is positively associated with affective needs.

H2b.

Rewards affordance is positively associated with social needs.

H2c.

Rewards affordance is positively associated with personal integrative needs.

H2d.

Rewards affordance is positively associated with social integrative needs.

Interaction affordance in livestreaming e-commerce enables consumers to communicate synchronously with streamers and fellow shoppers, thereby enhancing their sense of presence and offering them an experience akin to offline shopping. This real-time communication facilitates efficient and effective information dissemination among individuals [66]. Such interactions enable customers to virtually “experience” merchants’ products and services, diminishing the perception of distance and virtuality [67]. Through interaction, merchants and streamers can also gain consumer recognition, cultivating trust and loyalty [1]. This trust, in turn, spurs consumers to seek more information about marketed products, fulfilling their cognitive needs.

Several interaction mechanisms, such as bullet screens, microphone connections with anchors, and gifting, empower consumers to freely express and exchange subjective emotions and sentiments within livestreaming rooms [1]. Synchronized interactions can lead consumers to perceive resemblance with streamers, enhancing their sense of identification [68]. Related research has shown that people feel more joyful when communicating with others who share similar characteristics [69]. Thus, synchronized interactions in livestreaming commerce satisfy consumers’ affective needs. Both synchronized and unsynchronized interactions among consumers in live rooms or fan clubs enable them to share shopping experiences and forge social bonds, addressing their social needs.

Furthermore, interaction affordance enables consumers to freely express their opinions, questions, and experiences, facilitating self-recognition and a clearer understanding of their identity and values. Positive feedback from streamers or peers, such as likes and comments, motivates consumers to learn and improve, adjusting their behaviors or opinions based on others’ viewpoints and suggestions. The interactive platform also provides opportunities to share and validate their values, deepening their commitment to their beliefs and fulfilling the aspect of value consistency. Thus, interaction affordance fulfills consumers’ personal integrative needs.

Through real-time interaction, consumers engage, share opinions, and receive support from the consumer community, reinforcing their sense of belonging. The interactive nature of livestreaming encourages transparency and trust, facilitating the sharing of valuable information and resources that contribute to a more cohesive and informed community. Hence, interaction affordances in livestreaming e-commerce significantly satisfy consumers’ social integrative needs by fostering strong social connections, enhancing information sharing, and promoting cooperation and support within the community. Thus, we propose H3a–e.

H3a.

Interaction affordance is positively associated with cognitive needs.

H3b.

Interaction affordance is positively associated with affective needs.

H3c.

Interaction affordance is positively associated with social needs.

H3d.

Interaction affordance is positively associated with personal integrative needs.

H3e.

Interaction affordance is positively associated with social integrative needs.

Competition affordances, empowered by fan levels, leaderboards, and immediate challenges for winning coupons or flash sales, prompt consumers to think fast and react quickly during live shows to improve their scores or performance [70]. These activities necessitate continuous information gathering about products and services, stimulating consumers’ intellectual potential and fulfilling their need for intellectual growth and self-actualization, thereby satisfying their cognitive needs [48].

Leaderboards further motivate consumers’ innate desires, such as the pursuit of victory and achievement, the aspiration for social recognition, and the quest for status [46]. As fan levels and leaderboard rankings increase, consumers feel their efforts are recognized and valued, leading to a sense of pleasure [10]. Significant achievement or progress evokes a sense of achievement satisfaction, a common experience when overcoming challenges [71]. Additionally, when consumers participate in immediate challenges and flash sales and win the games, they also obtain a feeling of joy. Therefore, we posit that the competition affordance in livestreaming commerce can fulfill consumers’ affective needs.

In addition, a consumer’s advancement on the leaderboard underscores their competence in shopping and social interaction, along with dedication and perseverance. This progress, combined with self-learning and self-improvement, enhances their capabilities and skills [72,73]. Moreover, higher rankings are often associated with increased social recognition and status [74], generating social respect, confidence, and satisfaction, which are crucial components of personal integrative needs.

Group competition, another important mechanism in gamified livestreaming commerce, allows consumers to form groups like fan clubs to support their adored streamers. These groups often engage in competitive activities like team purchasing challenges or interactive contests, strengthening intergroup bonds. Such close-knit consumer communities not only reinforce consumers’ social identities but also bring in social and emotional support for them, thereby meeting their needs for social integration.

However, some negative effects may arise from over-competition. Excessive competition often puts different consumers in opposite relationships, which makes it difficult to form close social relationships. This opposing relationship may lead to consumers’ negative emotions, such as anxiety, frustration, and hostility, thereby hindering the satisfaction of their social needs. Thus, competition affordance is not associated with the satisfaction of social needs.

Taken together, we propose H4a–d.

H4a.

Competition affordance is positively associated with cognitive needs.

H4b.

Competition affordance is positively associated with affective needs.

H4c.

Competition affordance is positively associated with personal integrative needs.

H4d.

Competition affordance is positively associated with social integrative needs.

3.2. Influence of Psychological Needs on Participation Behaviors

In the scenario of livestreaming e-commerce, we consider customers’ purchases and continuous watching as two primary participation behaviors, reflecting the actual objectives of this commercial activity. Drawing upon the U&G theory, we argue that these two participation behaviors in livestreaming e-commerce are fundamentally influenced by consumers’ psychological needs.

In livestreaming e-commerce, synchronous interactions between buyers and sellers are significantly facilitated, making the transmission of product information extremely efficient. In contrast to traditional online shopping contexts, livestreaming shopping offers consumers the opportunity to acquire more authentic product information at a lower cost. This convenience in information acquisition facilitates the development of a more multifaceted and accurate grasp of the marketed objects, which in turn enhances their willingness to purchase [75].

Similarly, when consumers’ trust in the product, brand, and streamers is heightened through real-time product presentations and feedback sharing, their inclination to remain engaged in the livestream and continue watching is also augmented. Thus, we propose H5a and H5b.

H5a.

Cognitive needs are positively associated with purchase intentions.

H5b.

Cognitive needs are positively associated with continuous watching intentions.

Affective need, as defined by Katz et al. [50], represents an emotional satisfaction derived from pleasure and enjoyment. By engaging with livestreaming content, consumers can immerse themselves in the virtual world, obtain relaxation and emotional fulfillment, and alleviate negative emotions. According to O’Brien [76], when individuals perceive an activity as enjoyable, their intrinsic motivation increases, ultimately influencing their external behavior. In livestreaming e-commerce, satisfaction of consumers’ affective needs can be considered an incentive state, impacting both their purchase and continuous watching intentions.

Purchase intentions are commonly recognized as consumers’ spontaneous and strong willingness to engage in shopping. When consumers’ affective needs are met, they are more susceptible to environmental stimuli and may be induced to make impulsive purchases [77]. Furthermore, gamification design mechanisms, such as interactive lottery draws and flash sales, introduce a sense of fun and stimulate positive emotions among consumers. These positive emotions embody hedonic values for consumers and reinforce their trust in streamers, ultimately increasing their purchase intentions [78]. Extensive research has demonstrated that hedonic motivations, such as enjoyment and pleasure, drive users to continuously utilize information system services [79,80]. Once the gamified elements cater to consumers’ affective needs, they develop an emotional attachment to the content and desire to derive additional fun from it, thereby continuing to watch.

Taken together, we posit that consumers’ affective needs are positively linked with their purchase intentions and willingness to keep watching. Thus, we propose H6a and H6b.

H6a.

Affective needs are positively associated with purchase intentions.

H6b.

Affective needs are positively associated with continuous watching intentions.

Social needs signify an inherent desire to engage in communication and information exchange with others [81]. Within the domain of gamification, Suh et al. [82] demonstrated that gamified information systems can live up to users’ psychological needs, namely, competency, autonomy, and social needs, and augment their pleasure, thereby effectively fostering user participation. Similarly, Feng et al. [83] probed into the effectiveness of gamified elements in inducing users’ intrinsic motivation and affirmed that addressing social needs can inspire users to engage in sports and exhibit heightened loyalty toward fitness applications. Bitrián [84] further confirmed that fulfilling users’ social needs in a gamified app environment enhance user engagement, resulting in three favorable behavioral outcomes: a propensity to continue using the app, intentions to engage in word-of-mouth promotion, and positive ratings. Based on the above empirical evidence, we postulate that fulfillment of consumers’ social needs in live shopping is able to stimulate their intention to continue watching. Additionally, several studies have revealed that social values can elicit satisfaction among consumers and nurture their purchase intentions in online shopping environments [85,86]. Taken together, we propose H7a and H7b.

H7a.

Social needs are positively associated with purchase intentions.

H7b.

Social needs are positively associated with continuous watching intentions.

The need for personal integration indicates consumers’ desire to pursue self-confidence and status [50]. This need can be conceived as a motive for self-presentation, where online activities and behaviors serve as a medium for individuals to express their identities [87]. On social media platforms, individuals tend to curate and present an image that aligns with their desired self-portrayal, and they are more inclined to discuss topics that reinforce this image [88]. Similarly, in the context of livestreaming, viewers are more likely to show their images and discuss those created by others, thereby fulfilling their need for self-expression.

Consequently, consumers with a strong need for personal integration care more about livestreaming content and share their experiences with others frequently. This engagement fosters continuous watching behavior among these consumers. Furthermore, on e-commerce livestreaming platforms, consumers can earn a large number of points or experience rewards through their purchase activities. These rewards not only acknowledge their purchasing behavior but also cater to their desire for online ranking advancement. As consumers witness their rankings ascending, they may experience heightened confidence and satisfaction, which further augments their willingness to purchase products. The satisfaction derived from online ranking promotions reinforces this positive feedback loop, ultimately leading to an increase in consumers’ purchase intentions. Thus, we propose H8a and H8b.

H8a.

Personal integrative needs are positively associated with purchase intentions.

H8b.

Personal integrative needs are positively associated with continuous watching intentions.

The need for social integration captures the significance of others’ expectations and approvals in shaping our behaviors as social beings [50]. Individuals conform to subjective norms, driven by the desire to gain societal approval [89]. In the context of livestreaming e-commerce, these “others” encompass fellow consumers and streamers within the broadcast environment [90]. Streamers, motivated by remuneration, often cultivate an informal norm of purchasing behavior within their broadcast rooms [91]. The popularity of streamers, evidenced by a vast fan base and frequent interactions, can elicit consumers’ conformity tendencies [92]. When consumers comply with their peers’ behaviors, they are prone to following their behaviors and purchases [92].

Meanwhile, social interactions among consumers, such as commenting, liking, and sharing, reinforce their social attachment to the community [93]. Such a sense of attachment, a critical component of social integrative needs, can in turn increase consumers’ engagement, e.g., continuous watching [93,94]. Collectively, we believe that when consumers’ social integrative expectations are fulfilled, that is, once a sense of conformity or attachment to the livestreaming brands emerges, they are inclined to continue watching and purchasing in the live rooms. Thus, we propose H9a and H9b.

H9a.

Social integrative needs are positively associated with purchase intentions.

H9b.

Social integrative needs are positively associated with continuous watching intentions.

4. Research Method

4.1. Research Design and Data Collection

An online survey was employed to address our research questions, and the Credamo platform (www.credemo.com) was utilized to distribute the questionnaires. Credemo is a large data collection service platform, which has been widely used by over 3000 colleges and more than 4000 companies worldwide. Credamo is a professional research platform that can help users conduct surveys and experiments quickly and collect empirical data of good quality. It has approximately three million registered users who form a large sampling pool. We collected 378 questionnaires in total. We employed a filtering function (i.e., automatic jumping) in the questionnaire to ensure that only consumers who had prior experience with livestream shopping could fill out and submit the questionnaire. We also incorporated a filtering question in the questionnaire to judge whether the respondent was answering the question seriously. The filtering question that we used was “Please choose the “very unsatisfactory” from the options below. A. unsatisfactory. B. Very unsatisfactory. C. Satisfactory. D. Very satisfactory.” Invalid questionnaires were removed according to the following criteria: (a) excessively short completion time, (b) duplicate IP addresses, (c) selecting the same number for most of the scales, and (d) answering the filtering question wrongly. Finally, 354 valid questionnaires were obtained with an effective response rate of 93.65%. Table 2 summarizes the demographics of the respondents.

Table 2.

Demographics (N = 354).

4.2. Measures

The questionnaire mainly consisted of two parts, the latent variable measurement part and the basic information part. To ensure the effectiveness of all scales in the questionnaire, all survey items were adapted based on previous research. Dawes [95] found that the more grades the scale has, the more accurate the final result will be. Therefore, the questionnaire used a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) to measure the latent variables. Table 3 shows the scales and literature sources of this study.

Table 3.

Survey items.

4.3. Common Method Bias

It is suggested that common method bias (CMB) might be a threat to psychology and behavioral science research, especially in questionnaire studies [100]. To address the CMB issue in our constructs, we presented the independent, mediating, and dependent variables on separate pages to prevent the participants from recognizing causal relationships among the constructs. After collecting the questionnaires, we employed Harman’s single-factor test to detect potential CMB, following the method outlined by Malhotra et al. [100]. The results showed that the first factor accounted for less variation than the commonly accepted 50% standard. Subsequently, based on research by Williams et al. [101] and Liang et al. [102], a common method factor was included in the Partial Least Squares (PLS) model under investigation using Smart PLS 4.0. This model included all of the primary structural indicators studied. We then calculated the variances for each indicator within the main structural framework and the common method factor structure, respectively. As can be seen in Table 4, the results show that the mean value of substantively explained variance was 0.838, while the mean value of method-based variance was 0.018. There was a significant variance difference between these two methods, and a large number of method factor loadings were insignificant. Considering the tiny and insignificant magnitude of variance changes introduced by the common method factors, we conclude that the CMB imposes uncritical adversity on the current study.

Table 4.

Common method bias analysis.

5. Results

The Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) method was utilized to validate the proposed research hypotheses with the help of SmartPLS 4.0. First, PLS-SEM accommodates conditions of non-normality and remains effective even with small- to medium-sized samples such as the 354 participants in this study [103]. Second, PLS-SEM does not impose stringent requirements on data distribution, such as multivariate normality, which is a significant advantage in many research contexts. Third, PLS-SEM excels in handling complex theoretical models and is exploratory in nature [104], making it particularly suitable for the objective of the current study, which strives to explore the intricate relationships among different variables. Taken together, PLS-SEM emerges as a fitting analytical tool for our study.

5.1. Measurement Model Assessment

First, we assessed the multicollinearity of the indicators. To detect potential multicollinearity issues, we examined the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF scores of the measured data in Table 5 are all below the threshold value of 5, aligning with the recommended standard proposed by Hair et al. [105]. This finding suggests that multicollinearity is not a serious problem in the present study.

Table 5.

Measurement model convergent validity and reliability results.

Second, we gauged the convergent validity and reliability of the measurement model. Specifically, we checked the indicator loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). As presented in Table 5, the Cronbach’s alphas for all latent variables in the questionnaire are greater than 0.80, the factor loadings all surpass 0.80, and all the CR values exceed 0.9. These values offer strong support for excellent internal consistency and high reliability. Furthermore, the AVE for all variables is greater than 0.8, significantly exceeding the threshold value of 0.5, confirming good convergent validity for all the measurements.

Third, we checked the discriminant validity via the Fornell–Larcker criterion. Referencing Table 6, the square root values of the average variance extracted (AVE) for the latent variables, which are highlighted in bold on the diagonal of the correlation matrix, are larger than the off-diagonal correlations between the focal variable and other variables. This signifies significant distinctions among the latent variables, proving good discriminant validity for the measurement model.

Table 6.

Discriminant validity.

Based on the above analysis, the reliability and validity of the measurement model in this study are justified. Using this measurement model and the collected sample data, we proceeded with a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis to calculate the path coefficients among latent variables. This analysis also validated whether the theoretical hypotheses proposed in our study are empirically supported.

5.2. Structural Model Assessment

Adopting the PLS-SEM analysis with the Smart PLS 4.0, the research model underwent conceptual fitting and hypothesis testing to assess whether the hypotheses proposed in this paper were supported. Specifically, we evaluated the hypotheses in terms of path coefficients, significance levels, and assumed causality. Table 7 shows the results. Demographic variables (i.e., age, sex, education, and monthly salary) were added to the analysis as controls for purchase and continuous watching. All of the control variables were insignificantly associated with the two dependent variables.

Table 7.

Structural model analysis results.

According to the data on the impact of gamification affordance on consumers’ psychological needs, we observed the following: Achievement visualization affordance had significant positive effects on affective needs (β = 0.331, p < 0.001), social needs (β = 0.321, p < 0.001), personal integrative needs (β = 0.337, p < 0.001), and social integrative needs (β = 0.348, p < 0.001), supporting H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d. Similarly, rewards affordance positively affected affective needs (β = 0.369, p < 0.001), social needs (β = 0.257, p < 0.001), personal integrative needs (β = 0.277, p < 0.001), and social integrative needs (β = 0.226, p < 0.001), supporting H2a, H2b, H2c, and H2d. With regard to interaction affordance, the results showed that it had significant positive effects on cognitive needs (β = 0.650, p < 0.001), affective needs (β = 0.227, p < 0.001), social needs (β = 0.533, p < 0.001), and social integrative needs (β = 0.266, p < 0.001), supporting H3a, H3b, H3c, and H3e. However, it had no significant effect on personal integrative needs (β = 0.118, p = 0.104), rejecting H3d. In addition, competition affordance was positively correlated with cognitive needs (β = 0.207, p < 0.001), affective needs (β = 0.098, p < 0.05), personal integrative needs (β = 0.130, p < 0.05), and social integrative needs (β = 0.132, p < 0.001), supporting H4a, H4b, H4c, and H4d.

Regarding the influence of psychological needs on consumer participation behavior, our findings were as follows: Cognitive needs had a significant positive effect on purchase intentions (β = 0.253, p < 0.001) and continuous watching intentions (β = 0.271, p < 0.001), supporting H5a and H5b. Affective needs were positively correlated with continuous watching intentions (β = 0.239, p < 0.001) but not with purchase intentions (β = 0.096, p = 1.653), rejecting H6a but supporting H6b. Social needs were positively correlated with purchase intentions (β = 0.358, p < 0.001) and continuous watching intentions (β = 0.328, p < 0.001), supporting H7a and H7b. However, personal integrative needs had no significant relationship with either purchase intentions (β = −0.003, p = 0.936) or continuous watching intentions (β = 0.070, p = 0.092), rejecting H8a and H8b. The need for social integration was positively correlated with purchase intentions (β = 0.248, p < 0.001) but not with continuous watching intentions (β = 0.070, p = 0.213), supporting H9a and rejecting H9b.

6. Discussion

This study, grounded in the U&G theory, explored gamification as an engagement factor that fulfills consumers’ diverse psychological needs, thereby encouraging purchases and continuous watching on livestream shopping platforms. The effects of gamification affordances, rather than specific gamified elements or mechanics, were probed into, addressing the inconsistent results in prior gamification marketing research and offering a more accurate perspective on gamification effectiveness. The findings support gamification as a meaningful strategy to enhance consumer retention and purchasing on livestreaming e-commerce platforms.

The data analysis results revealed that, except for interaction affordance—which exhibited no significant effect on personal integrative needs—other gamification affordances positively and significantly impact corresponding psychological needs. Specifically, achievement visualization affordance enables consumers to clearly understand their achievements and contributions on livestreaming e-commerce platforms. This intuitive form of achievement expression generates feelings of accomplishment and superiority for customers, fulfilling their quests for fun, social interaction, self-improvement, and social recognition [106]. Consequently, achievement visualization affordance positively influences consumers’ affective, social, personal, and social integrative needs.

Rewards affordance, through offering virtual or monetary rewards to the most active consumers, signifies recognition and appreciation. This not only fulfills their social needs by fostering a sense of belonging but also meets their emotional needs through positive reinforcement. Additionally, rewards align with personal goals, enhancing self-esteem and accomplishment, thereby addressing personal integrative needs. Apart from that, they also encourage interaction and cooperation, strengthening social bonds. In summary, reward affordance positively impacts consumers’ affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative needs.

Interaction is pervasive in e-commerce livestreaming. Through interaction with streamers and other consumers, consumers can obtain more information, eliminate loneliness, maintain good relationships with others [1], and thus satisfy their cognitive, affective, social, and social integrative needs. However, the current data analysis outputs indicated that interaction affordance does not significantly correlate with personal integrative needs. Such a finding contradicts that of Che et al. [28], who noticed that e-commerce consumers can simultaneously achieve personal and social integration benefits. This might be because a significant portion of gamified interaction mechanisms provided in livestreaming commerce platforms (e.g., lucky draws, voting, and Q&A with the streamers) are designed to induce consumers’ immediate positive emotions and motivate their short-term behaviors, such as impulse buying and continuous watching. Hence, such interaction mechanisms make it difficult to fulfill consumers’ personal integrative needs, which are on a deeper level. Consumers’ personal integrative needs are more associated with the recognition of brand value and confidence enhancement through repetitive participation, which requires a longer time to cultivate. Therefore, interaction affordance alone is unable to enhance the personal integrative needs in livestreaming commerce.

Finally, competition affordance not only displays the information of high-level users but also motivates consumers to improve their ranking through individual efforts or group collaboration. This feature significantly impacts consumers’ cognitive, affective, personal integrative, and social integrative needs. Through showcasing the achievements of top performers, competition affordance urges consumers to strive for improvement, enhancing their self-awareness and cognitive development. Liu et al. [107] supported this view, arguing that competition-related gamification features and elements can encourage consumers to improve their performance, ultimately increasing their ability and self-efficacy in a gamified context. Competition also fosters emotional satisfaction in consumers when they win challenges and achieve a certain goal, thereby addressing their affective needs. Furthermore, group-level competition (e.g., PK between different streamers’ fan clubs) reinforces consumers’ sense of belonging, fulfilling their social integrative needs.

As for the effects of psychological needs on consumer behaviors, the analysis results offered several insights. Cognitive needs are positively correlated with consumers’ purchase and continuous watching intentions. One possible reason is that livestreaming provides additional value aside from the benefits initially guaranteed for consumers [108]. The information learned from streamers or other consumers through gamified elements satisfies their cognitive needs, enabling them to purchase more rationally [75]. Similarly, consumers’ desire for more information fuels their continuous watching intentions [109]. In contrast, the satisfaction of affective needs keeps consumers watching but is unable to motivate them to buy. This is because consumers experience relaxation and happiness while watching livestreaming, and to maintain this psychological state, they will continue to watch. However, purchase behavior might not be a direct outcome of pleasure. Purchase requires additional monetary expenditure and cannot be easily induced solely by positive emotions. Most consumers are lured to buy on live shopping platforms by the considerable discounts offered and real-time product presentation. Therefore, pleasure and fun, although important, cannot drive sales alone.

As expected, the satisfaction of social needs prominently drives the purchase and continuous watching behaviors of consumers. When consumers interact with anchors or their peers, they gain a better consumption experience that combines the convenience of quick shopping with offline-like services, thereby being more likely to purchase and stay longer in the live rooms. As demonstrated by Bao et al. [110], high sociability reinforces positive consumer attitudes and leads to higher engagement.

However, contrary to our expectations and inconsistent with the results of Che et al. [28] and Jang et al. [111], who noticed a significant link between consumers’ integration benefits and purchases, personal integrative needs about self-actualization and status enhancement do not significantly correlate with purchase or continuous watching intentions. This might result from the fact that the need for personal integration seeks praise and attention from others, whereas purchase and continuous watching intentions are personal choices. Hence, there are no significant relationships among them. In contrast, social integrative needs, which relate to group norms and social identity, show a significant positive correlation with purchase intentions. Consumers perceive themselves as belonging to the same group as other co-viewers in livestreaming, leading them to believe that purchasing the same products as their peers is reliable and beneficial. However, despite enhancing purchase intentions, social integrative needs do not significantly influence continuous watching intentions. We speculate that this might be due to two potential reasons. First, the low threshold for watching livestreams. Any user can become an audience member without much cost. Therefore, consumers with strong community norms might still wander around in different live rooms, seeking diverse content that fits with their changing interests and needs, rather than faithfully staying in a particular live room. Second, the limited support for watching streamers and brands. Continuous watching by an individual can only create a single instance of traffic for streamers and brands, whereas purchasing results in actual profit for them. Therefore, consumers with a high sense of belonging will support streamers and brands by purchasing instead of merely watching.

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

The results of this study offer various academic contributions in the domains of e-commerce marketing and human-computer interaction. First, this work contributes to the growing research trend on marketing in livestreaming commerce by interpreting consumers’ participation behaviors from the new angle of gamification. Previous research investigating the predictors of consumer behaviors in live shopping has primarily focused on streamer-related characteristics and consumer-related factors [112]. For instance, Chandrruangphen et al. [113] examined the effects of celebrities’ trustworthiness and communication efforts on consumers’ shopping intentions, whereas Wu and Huang [78] explored the specific hedonic and utilitarian motivations for consumers’ purchases in livestreaming commerce. Some scholars have also looked at the platform technicalities (e.g., IT affordance, synchronicity, and visibility) and analyzed their influence on consumer behaviors [114,115]. The current study is innovative in its identification of four gamification affordances (i.e., achievement visualization, rewards, interaction, and competition) that influence consumers’ participation behaviors. Only a very limited amount of research has examined livestreaming commerce from a gamification perspective [14,15,68]. These studies have focused on specific gamification elements rather than the affordances that are enabled. Echoing the recent trend of examining gamification from an affordance lens [11,21], the current research delineated four gamification affordances in livestreaming commerce and investigated their effects on consumer behaviors, contributing to a more accurate understanding of gamification effects.

Second, this study adds to the gamification research arena by enriching the psychological outcomes of gamification. Past research has proposed the well-received “Gamification Affordances–Psychological Outcomes–Behavioral Outcomes” framework to describe the effect paths of gamification [46]. Various attitudes and motivations have been identified as the psychological outcomes that associate gamification with behavioral outcomes [63,64]. Building on related research in livestreaming commerce [26,52], the current research creatively adopted the Uses and Gratification Theory to propose five psychological needs satisfaction (i.e., cognitive, affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative) as the psychological outcomes of gamification. Specifically, we proposed a new research model that helps us better explore how the new media of e-commerce livestreaming, with its gamification design, meets these psychological needs and ultimately influences consumer behaviors. In doing so, the present study provides a more nuanced understanding of how consumers interact and are influenced by gamification designs in livestreaming commerce.

Third, this study provides a holistic examination of consumers’ participation behaviors in the scenario of livestreaming commerce. Existing scholarly endeavors either delved into consumers’ non-transactional behaviors (e.g., watching and following) [109,115] or centered around transactional behaviors (e.g., hedonic consumption and impulsive consumption) [75]. There is scant research investigating both kinds of behaviors in a holistic model. By incorporating continuous watching and purchasing into the model and discovering their differentiated antecedents, the current study contributes to a more comprehensive and insightful understanding of participation motivators for livestreaming commerce consumers.

6.2. Practical Implications

There are also several practical implications generated from the present study. To enhance consumers’ experiences in e-commerce livestreaming and foster users’ engagement, livestreaming platforms and streamers should prioritize and skillfully incorporate various gamification elements. For brand merchants, the strategic use of gamification elements can effectively elevate the ambiance of the broadcast room, achieving superior promotional and sales outcomes. For platforms, the ongoing development and optimization of gamification designs within livestreaming platforms can not only attract a vast array of consumers [116], but also bridge the gap between consumers, platforms, hosts, and streamers [117].

Specifically, this study found that the four gamification affordances can fulfill the differentiated psychological needs of consumers. First, both achievement visualization affordance and rewards affordance can satisfy consumers’ affective, social, personal integrative, and social integrative needs. Therefore, platform designers should try to make consumers’ achievements easily visible to both themselves and other consumers in the same live rooms (e.g., using pop-up functions to notify consumers about their achievements or demonstrating their immediate achievements publicly on the bulletin board). Consumers should be frequently rewarded with monetary or non-monetary incentives during gamified livestreaming activities. Such mechanisms can bring about pleasure and joyfulness for consumers and enhance their sense of self-value and belonging, fostering them to socialize with streamers and other consumers more intensively. Second, interaction affordance feeds the consumers’ cognitive, affective, social, and social integrative needs. Hence, various gamified interaction tools (e.g., Q&A challenges, connecting with streamers with a microphone, thumbs up, and gifting) should be devised to facilitate synchronous interactions between consumers and streamers/co-viewers. Real-time communications can equip consumers with sufficient product information to make purchase decisions, address their need for emotional exchange and socialization, and strengthen their identification and attachment to brands. Third, competition affordance can be utilized to meet consumers’ cognitive, affective, personal integrative, and social integrative needs. Individual competition mechanisms, such as fan levels and leaderboards, can be adapted to prompt consumers to seek more product knowledge, set personal objectives, and compete with superior others, whereas group competition, such as the PK between fan clubs of different streamers, can reinforce consumers’ loyalty to their beloved streamers.

Apart from that, empirical findings from this study suggest that consumers’ continuous watching and purchase behavior are induced by the satisfaction of different psychological needs. Purchasing, the most critical purpose of livestreaming marketing activities, is realized after the accommodation of cognitive, social, and social integrative needs. Given that, to boost their sales performance, platform designers and brand marketers should design various measures to transmit abundant product information to consumers, all kinds of communication channels should be opened up to them, and their emotional and cognitive attachment to the brands/streamers should be established. In contrast, consumers’ continuous watching behavior is driven by the fulfillment of cognitive, affective, and social needs. Given the platform rule that lives rooms with more traffic (i.e., viewers) can have a higher exposure rate in the search results, livestreaming brands should try their best to generate cognitive, emotional, and social values for their viewers in live shows to retain them.

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

This study also acknowledges several limitations. First, the use of questionnaires to collect data has inherent limitations in capturing the real behavior of consumers. To overcome this issue, future research could employ tools such as application programming interfaces (APIs) or collaborate with livestreaming commerce platforms to gather actual behavioral data of consumers. Second, our research focused exclusively on Chinese e-commerce livestreaming consumers and the gamification affordances found on Chinese livestreaming platforms. Livestreaming commerce platforms in other countries might have different gamification elements and related affordances because of their idiosyncratic cultures. Future research should be replicated in different countries or regions to enhance the generalizability of the results. Third, despite our efforts to incorporate relevant psychological needs into the research model, we cannot rule out the potential influence of other gratifications applied to the livestreaming commerce context, such as trend-setting [118] and cost-saving [119]. Future studies should incorporate more gratification variables as mediating factors into the model. Lastly, with regard to dependent variables, this study chose to focus on purchase and continuous watching behaviors. However, diverse consumer participation behaviors occur in the live shopping context, including helping others, providing word-of-mouth evaluations, asking questions, and tipping/gifting. Hence, future research could consider the impacts of gamification on these participation behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. and Y.F.; methodology, X.L. and Y.F.; software, X.L.; validation, C.Y., Y.F. and X.L.; formal analysis, C.Y. and Y.F.; investigation, C.Y. and Y.F.; resources, B.N.; data curation, X.L. and B.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.F. and B.N.; visualization, C.Y.; supervision, C.Y. and Y.F.; project administration, C.Y. and Y.F.; funding acquisition, C.Y. and Y.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guangdong Philosophy and Social Science Planning Office, grant number GD23XGL004; the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, grant number 2023A1515012262; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 72334004 and 71971143; and the Excellent Youth Project of Shenzhen University, grant number ZYQN2305.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were collected via a survey on the Credemo platform (www.credemo.com). The raw data are not shared publicly, but the full questionnaire is provided in Table 3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, A.; Lu, Y. Trust development in live streaming commerce: Interaction-based building mechanisms and trust transfer perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2024, 124, 3218–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q. Consumer engagement in live streaming commerce: Value co-creation and incentive mechanisms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shao, Z.; Li, X.; Feng, Y. Gamification and online impulse buying: The moderating effect of gender and age. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T.; Ho, T.Y.; Xie, H. Building brand engagement in metaverse commerce: The role of branded non-fungible tokens (BNFTs). Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 58, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobon, S.; Ruiz-Alba, J.L.; Garcia-Madariaga, J. Gamification and online consumer decisions: Is the game over? Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 128, 113167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Chen, M.C. How gamification marketing activities motivate desirable consumer behaviors: Focusing on the role of brand love. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 88, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, L. Having fun while receiving rewards?: Exploration of gamification in loyalty programs for consumer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatautis, R.; Vitkauskaite, E.; Gadeikiene, A.; Piligrimiene, Z. Gamification as a Mean of Driving Online Consumer Behaviour: SOR Model Perspective. Inz. Ekon.-Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Transforming homo economicus into homo ludens: A field experiment on gamification in a utilitarian peer-to-peer trading service. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, A.; Wagner, C. How gamification of an enterprise collaboration system increases knowledge contribution: An affordance approach. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Du, H.S.; Shen, K.N.; Zhang, D.P. How gamification drives consumer citizenship behaviour: The role of perceived gamification affordances. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 64, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Xu, S.X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, N. The Needs-Affordances-Features Perspective for the Use of Social Media. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, V.G.; Baines, T.; Baldwin, J.; Ridgway, K.; Petridis, P.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Uren, V.; Andrews, D. Using gamification to transform the adoption of servitization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 63, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.E.; Yu, C. Exploring gamification for live-streaming shopping—Influence of reward, competition, presence and immersion on purchase intention. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57503–57513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayola, F.; Graciela, V.; Chandra, V.; Sukmaningsih, D.W. Impact of Gamification Elements on Live Streaming E-Commerce (Live Commerce). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 245, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B.; Nguyen, Y.T.H. Human–human interactions’ influence on impulse-buying intention in live commerce: The roles of Guanxi, co-viewer trust, and gamification. J. Promot. Manag. 2024, 30, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Cheah, J.H.; Liu, Y. To stream or not to stream? Exploring factors influencing impulsive consumption through gastronomy livestreaming. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3394–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electron. Mark. Int. J. Networked Bus. 2017, 27, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.Y.; Matz, R.; Luo, L.; Xu, C. Gamification for value creation and viewer engagement in gamified livestreaming services: The moderating role of gender in esports. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Lin, Y.; Mou, J. Unpacking the effect of gamified virtual CSR cocreated on users? pro-environmental behavior: A holistic view of gamification affordance. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shao, Z.; Benitez, J.; Zhang, R. How to improve user engagement and retention in mobile payment: A gamification affordance perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2023, 168, 113941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.K.; Chen, C.W.; Silalahi, A.D.K. Understanding consumers’ purchase intention and gift-giving in live streaming commerce: Findings from SEM and fsQCA. Emerg. Sci. J. 2022, 6, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. To shop or not: Understanding Chinese consumers’ live-stream shopping intentions from the perspectives of uses and gratifications, perceived network size, perceptions of digital celebrities, and shopping orientations. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 59, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Ting, D.H. E-shopping: An analysis of the uses and gratifications theory. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2012, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]