A Model of Perception of Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure on Online Social Networks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Development

2.1. Previous Work on Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure of Osns

2.2. Petronio’s Communications Privacy Management Theory

2.3. Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure on Osns and Websites Models

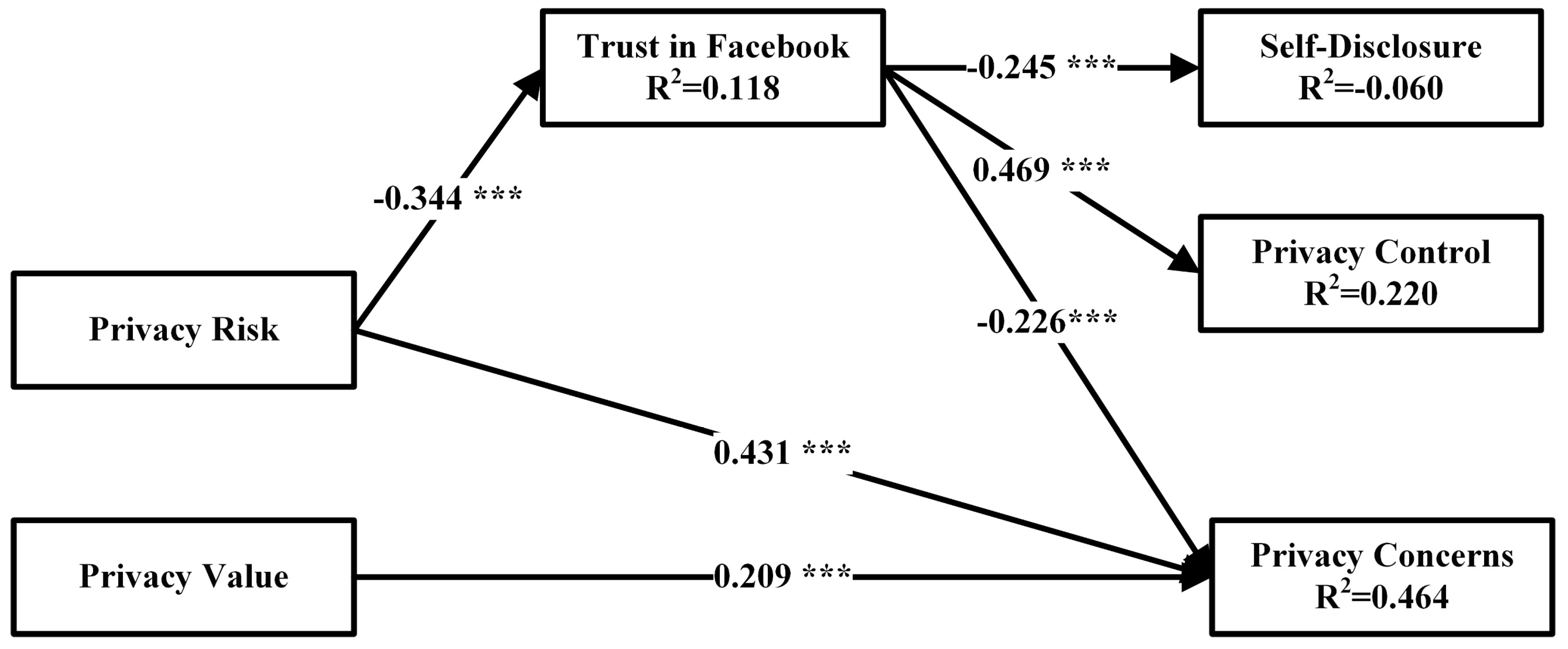

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Privacy Risk

3.2. Privacy Value

3.3. Trust in Facebook

4. Research Methods

4.1. Data Collection and Participants

4.2. Measures

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Model Analysis

5.2. Testing Research Hypotheses

6. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ellison, N.B.; Boyd, D.M. Sociality Through Social Network Sites. In The Oxford Handbook of Internet Studies; Dutton, W.H., Ed.; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Chiu, P.-Y.; Lee, M.K.O. Online social networks: Why do students use facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P. Student Favorite: Facebook and Motives for its Use. Southwest. J. Mass Commun. 2008, 23, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook Newsroom—Stats. Available online: https://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/ (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Laufer, R.S.; Wolfe, M. Privacy as a Concept and a Social Issue: A Multidimensional Developmental Theory. J. Soc. Issues 1977, 33, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I. The Environment and Social Behavior: Privacy, Personal Space, Territory, and Crowding; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.: Monterey, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, J.L. The Self in Social Psychology. In Self-disclosure; Wegner, D., Vallacher, R., Eds.; Oxford University: London, UK, 1980; pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, F.; Zhao, B.; Yu, H.; Xu, A.; Hao, Y. Theoretical research on structural equation model based on principle of entropy. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on E-Business and E-Government (ICEE), Shanghai, China, 6–8 May 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Cui, X. A parameter estimation method for structural equation model based on generalized maximum entropy. In Proceedings of the 2012 Third International Conference on Intelligent Control and Information Processing, Dalian, China, 15–17 July 2012; pp. 569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, T.L.; Mittelhammer, R.; Cardell, N.S. Generalized Maximum Entropy Analysis of the Linear Simultaneous Equations Model. Entropy 2014, 16, 825–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, T.L.; Warkentin, M.; Collignon, S.E. A dual privacy decision model for online social networks. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronio, S. Boundary of Privacy: Dialectics of Disclosure; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, B.C.F.; Land, L. The effects of general privacy concerns and transactional privacy concerns on Facebook apps usage. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, J.; Lampinen, A.; Smolen, A. Privacy: Is There an App for That? In Proceedings of the Symposium On Usable Privacy and Security, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20–22 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K.; Kaufman, J.; Christakis, N. The Taste for Privacy: An Analysis of College Student Privacy Settings in an Online Social Network. J. Comput. Mediat. Comm. 2008, 14, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reicher, S.D.; Spears, R.; Postmes, T. A Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Phenomena. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 6, 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaboldi, V.; Guazzini, A.; Passarella, A. Egocentric online social networks: Analysis of key features and prediction of tie strength in Facebook. Comput. Commun. 2013, 36, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, R.; Acquisti, A. Information Revelation and Privacy in Online Social Networks (The Facebook case). In Proceedings of the ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society (WPES), Alexandria, VA, USA, 7 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Acquisti, A.; Gross, R. Imagined Communities: Awareness, Information Sharing, and Privacy on the Facebook. In Privacy Enhancing Technologies; Danezis, G., Golle, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4258, pp. 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski, P.J.; Knijnenburg, B.P.; Lipford, H.R. Making privacy personal: Profiling social network users to inform privacy education and nudging. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2017, 98, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, N.; Shen, X.-L.; Zhang, J.X. Location information disclosure in location-based social network services: Privacy calculus, benefit structure, and gender differences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Duong, T.D.; Chen, C.C. Intention to disclose personal information via mobile applications: A privacy calculus perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. A multi-level model of individual information privacy beliefs. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2014, 13, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaig, K.S.; Segars, A.H.; Grover, V.; Fiedler, K.D. A model of consumers’ perceptions of the invasion of information privacy. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, A.; Zollo, F.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Scala, A. How News May Affect Markets’ Complex Structure: The Case of Cambridge Analytica. Entropy 2018, 20, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Chen, J.V. Aligning principal and agent’s incentives: A principal–agent perspective of social networking sites. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 3091–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-H. The effects of trust, security and privacy in social networking: A security-based approach to understand the pattern of adoption. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, S.; Chau, P.Y.K.; Cao, Y. Dynamics between the trust transfer process and intention to use mobile payment services: A cross-environment perspective. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, S.; Contena, B. Privacy, trust and control: Which relationships with online self-disclosure? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Michael, K.; Chen, X. Factors affecting privacy disclosure on social network sites: An integrated model. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 13, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Park, S.-T.; Ko, M.-H. A Study of Factors that Affect the Right to be Forgotten and Self-Disclosure Intent in SNS. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec Zlatolas, L.; Welzer, T.; Heričko, M.; Hölbl, M. Privacy antecedents for SNS self-disclosure: The case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Min, Q.; Zhai, Q.; Smyth, R. Self-disclosure in Chinese micro-blogging: A social exchange theory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xie, W. Teens’ concern for privacy when using social networking sites: An analysis of socialization agents and relationships with privacy-protecting behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, P.M.; Schmidt, L.A. Is shyness context specific? Relation between shyness and online self-disclosure with and without a live webcam in young adults. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Heo, J. Visiting theories that predict college students’ self-disclosure on Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbaugh, E.E.; Ferris, A.L. Facebook self-disclosure: Examining the role of traits, social cohesion, and motives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heirman, W.; Walrave, M.; Vermeulen, A.; Ponnet, K.; Vandebosch, H.; Van Ouytsel, J.; Van Gool, E. An open book on Facebook? Examining the interdependence of adolescents’ privacy regulation strategies. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2016, 35, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney Walton, S.; Rice, R.E. Mediated disclosure on Twitter: The roles of gender and identity in boundary impermeability, valence, disclosure, and stage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, B.D.; Child, J.T. Friend or not to friend: Coworker Facebook friend requests as an application of communication privacy management theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisekka, V.; Bagchi-Sen, S.; Rao, H.R. Extent of private information disclosure on online social networks: An exploration of Facebook mobile phone users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2722–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, H.; Kim, J. Why do people share their context information on Social Network Services? A qualitative study and an experimental study on users’ behavior of balancing perceived benefit and risk. Int J. Hum. Comput. St. 2013, 71, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wolf, R.; Willaert, K.; Pierson, J. Managing privacy boundaries together: Exploring individual and group privacy management strategies in Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Dinev, T.; Smith, H.J.; Hart, P. Examining the Formation of Individual’s Privacy Concerns: Toward an Integrative View. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Paris, France, 21–23 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Dinev, T.; Smith, J.; Hart, P. Information Privacy Concerns: Linking Individual Perceptions with Institutional Privacy Assurances. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 12, 798–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, A.; Vitrano, J.; Gengo, N.J. Rationality-based beliefs affecting individual’s attitude and intention to use privacy controls on Facebook: An empirical investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The impact of disposition to privacy, website reputation and website familiarity on information privacy concerns. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 57, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Lankton, N.; Tripp, J. Social Networking Information Disclosure and Continuance Intention: A Disconnect. In Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 January 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. Living a private life in public social networks: An exploration of member self-disclosure. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H.; Kolesnikova, E.; Guenther, O. “It won’t happen to me!”: Self-disclosure in online social networks. In Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–9 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.W.; Huang, S.Y.; Yen, D.C.; Popova, I. The effect of online privacy policy on consumer privacy concern and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Member use of social networking sites—An empirical examination. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An extended privacy calculus model for E-commerce transactions. Inform. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Gupta, S.; Rosson, M.B.; Carroll, J.M. Measuring Mobile Users’ Concerns for Information Privacy. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, 16–19 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Min, J.; Lee, H. Antecedents of social presence and gratification of social connection needs in SNS: A study of Twitter users and their mobile and non-mobile usage. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tow, W.N.-F.H.; Dell, P.; Venable, J. Understanding information disclosure behaviour in Australian Facebook users. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.L.; Quan-Haase, A. Information Revelation and Internet Privacy Concerns on Social Network Sites: A Case Study of Facebook. In Proceedings of the Communities and Technologies, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA, 25–27 June 2009; pp. 265–274. [Google Scholar]

- Al Omoush, K.S.; Yaseen, S.G.; Atwah Alma’aitah, M. The impact of Arab cultural values on online social networking: The case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2387–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contena, B.; Loscalzo, Y.; Taddei, S. Surfing on Social Network Sites: A comprehensive instrument to evaluate online self-disclosure and related attitudes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R.; Yuki, M.; Ito, N. A socio-ecological approach to national differences in online privacy concern: The role of relational mobility and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H.; Veltri, N.F.; Günther, O. Self-disclosure and Privacy Calculus on Social Networking Sites: The Role of Culture. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2012, 4, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppolino Perfumi, S.; Bagnoli, F.; Caudek, C.; Guazzini, A. Deindividuation effects on normative and informational social influence within computer-mediated-communication. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collodi, S.; Panerati, S.; Imbimbo, E.; Stefanelli, F.; Duradoni, M.; Guazzini, A. Personality and Reputation: A Complex Relationship in Virtual Environments. Future Internet 2018, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, J.G.; Wilson, D.; Valacich, J.S.; Byrd, M.D. Saving face on Facebook: Privacy concerns, social benefits, and impression management. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronio, S.; Durham, W. Communication Privacy Management Theory: Significance for Interpersonal Communication. In Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication: Multiple Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Braithwaite, D.O., Schrodt, P., Eds.; Sage Publications: Saunders Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Norcie, G.; Komanduri, S.; Acquisti, A.; Leon, P.G.; Cranor, L.F. “I regretted the minute I pressed share”: A qualitative study of regrets on Facebook. In Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20–22 July 2011; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Internet Statistics and Population for European Union. Available online: http://www.internetworldstats.com/europa.htm#si (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Cook, R.D.; Weisberg, S. Residuals and Influence in Regression; Chapman and Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, J.; Nehmad, E. Internet social network communities: Risk taking, trust, and privacy concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. Internet privacy concerns and their antecedents—measurement validity and a regression model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2004, 23, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnaly, J. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, F.M. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 1991; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Segars, A.H.; Grover, V. Re-Examining Perceived Ease of Use and Usefulness: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. MIS Q. 1993, 17, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Todd, P.A. On the Use, Usefulness, and Ease of Use of Structural Equation Modeling in MIS Research: A Note of Caution. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual Quant 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofer, M.; Hinz, O.; Muntermann, J.; Roßnagel, H. The Economic Impact of Privacy Violations and Security Breaches. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2014, 6, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Independent Variables | Mediator Variables | Dependent Variables | Tested on Users Of | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy awareness, Privacy social norm, Perceived effectiveness of privacy policy, Perceived effectiveness of privacy seal | Privacy risk, Disposition to privacya, Privacy control, Perception of intrusion | Privacy concerns | Financial and healthcare websites, electronic commerce, and OSNs | [45,46] |

| Resource vulnerability, Threat severity, Privacy risk, Privacy intrusion | Cost of not using privacy controls, Social norm, Attitude, Perceived behavioral control | Intention to use privacy controls | [47] | |

| Privacy experience, Website reputation, Website familiarity, Perceived benefits | Disposition to privacy a, Site-specific privacy concerns | Behavioral intention | websites | [48] |

| Privacy concern, Information sensitivity, Trusting beliefs, Perceived usefulness, Enjoyment | Information disclosure b | Continuance intention | OSNs | [49] |

| Extroversion, Perceived critical mass, Perceived internet risk, Privacy value | Attitude | Privacy self-disclosure behaviors | OSNs | [50] |

| Perceived likelihood, Perceived damage, Privacy enjoyment | Privacy concerns | Self-disclosure | OSNs | [51] |

| Privacy policy (Notice, Choice, Access, Security, Enforcement) | Online privacy concern, Trust | Willingness to provide information b | Internet | [52] |

| Variable | Analysis Results |

|---|---|

| Gender | Male 44.0% Female 56.0% |

| Finished education | Less than high school 1.5% High school 50.7% Bachelor’s degree 24.4% Master’s degree or higher 23.4% |

| Age | M 26.73 SD 8.21 |

| Number of friends on Facebook | M 441.06 SD 393.54 |

| Percentage of Facebook Friends whom the user doesn’t know in person | M 11.42% SD 19.26% |

| Average Facebook use per day | 0–10 min per day 13.0% 10–30 min per day 35.4% 30–60 min per day 28.0% More than 60 min per day 23.6% |

| Experience with Internet use (7-point Likert scale) | M 6.35 SD 0.99 |

| Experience with Facebook use (7-point Likert scale) | M 5.88 SD 1.25 |

| Constructs | Code | Items | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy risk | PR1 | I think giving personal information on Facebook would be risky. | [45,47] |

| PR2 | Providing my personal information to Facebook would involve many unexpected issues. | ||

| PR3 | Facebook may use my personal information inappropriately. | ||

| Privacy value | PV1 | To me, keeping my privacy online is the most important thing. | [45,46,48] |

| PV2 | I see greater importance in keeping personal information private compared to others. | ||

| PV3 | I am more concerned with potential threats to my personal privacy compared to others. | ||

| Trust in Facebook | TR1 | Facebook is a trustworthy OSN. | [48,49,70] |

| TR2 | Facebook has a good reputation. | ||

| TR3 | I can conduct my privacy on Facebook. | ||

| TR4 | I will recommend that others use Facebook. | ||

| Self-disclosure | SD1 | My profile on Facebook is filled with details. * | [22,50,51,52] |

| SD2 | My profile on Facebook tells a lot about me. * | ||

| SD3 | On Facebook, I disclose a lot of information about me. * | ||

| SD4 | I am prepared to provide personal information on OSN. * | ||

| SD5 | I am forced to submit personal information on OSNs. | ||

| Privacy control | PCt1 | I think I have control over who can access my personal information that is collected by Facebook. | [44,45,46] |

| PCt2 | I think I control who has access to my personal information on Facebook. | ||

| PCt3 | I think I have control over how Facebook uses personal information. | ||

| PCt4 | I think I can control my personal information which I provide to Facebook. | ||

| Privacy concerns | PCs1 | It upsets me when I have to put personal information on Facebook. | [24,45,46,48,49,71] |

| PCs2 | I am concerned that too much personal information about me is being collected by OSNs. | ||

| PCs3 | I’m concerned that my personal information could be accessed by unauthorized people. | ||

| PCs4 | I am concerned that there may be misuse of the information I submit on Facebook. | ||

| PCs5 | I am concerned when I have to submit information on OSNs. |

| Item | Factor Loading | Constructs | No. of Items | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR1 | 0.824 | Privacy risk | 3 | 0.800 |

| PR2 | 0.852 | |||

| PR3 | 0.603 | |||

| PV2 | 0.452 | Privacy value | 2 | 0.772 |

| PV3 | 0.484 | |||

| TR1 | 0.843 | Trust in Facebook | 3 | 0.824 |

| TR2 | 0.726 | |||

| TR3 | 0.770 | |||

| SD1 | 0.775 | Self-disclosure | 4 | 0.851 |

| SD2 | 0.858 | |||

| SD3 | 0.789 | |||

| SD4 | 0.608 | |||

| PCt1 | 0.987 | Privacy control | 2 | 0.788 |

| PCt2 | 0.683 | |||

| PCs1 | 0.756 | Privacy concerns | 5 | 0.901 |

| PCs2 | 0.902 | |||

| PCs3 | 0.755 | |||

| PCs4 | 0.714 | |||

| PCs5 | 0.834 |

| Notation | Recommended Value | Measurement Model |

|---|---|---|

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.903 |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.923 |

| NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.903 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.10 | 0.074 |

| CR | AVE | Privacy Risk | Privacy Value | Trust in Facebook | Self-Disclosure | Privacy Control | Privacy Concerns | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy risk | 0.881 | 0.587 | 0.766 | |||||

| Privacy value | 0.864 | 0.642 | 0.314 | 0.801 | ||||

| Trust in Facebook | 0.893 | 0.615 | 0.130 | 0.003 | 0.784 | |||

| Self-disclosure | 0.910 | 0.594 | 0.047 | 0.041 | 0.062 | 0.771 | ||

| Privacy control | 0.883 | 0.689 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 0.228 | 0.001 | 0.830 | |

| Privacy concerns | 0.944 | 0.654 | 0.401 | 0.215 | 0.157 | 0.015 | 0.031 | 0.809 |

| H | Path | Standardized Coefficient β | T-Statistic | The Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | PR | - | TR | −0.413 *** | −6.851 | Accepted |

| H1b | PR | - | PCs | 0.627 *** | 7.711 | Accepted |

| H2 | PV | - | PCs | 0.231 *** | 4.118 | Accepted |

| H3a | TR | - | SD | −0.284 *** | −5.183 | Accepted |

| H3b | TR | - | PCt | 0.355 *** | 7.528 | Accepted |

| H3c | TR | - | PCs | −0.274 *** | −5.525 | Accepted |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nemec Zlatolas, L.; Welzer, T.; Hölbl, M.; Heričko, M.; Kamišalić, A. A Model of Perception of Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure on Online Social Networks. Entropy 2019, 21, 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21080772

Nemec Zlatolas L, Welzer T, Hölbl M, Heričko M, Kamišalić A. A Model of Perception of Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure on Online Social Networks. Entropy. 2019; 21(8):772. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21080772

Chicago/Turabian StyleNemec Zlatolas, Lili, Tatjana Welzer, Marko Hölbl, Marjan Heričko, and Aida Kamišalić. 2019. "A Model of Perception of Privacy, Trust, and Self-Disclosure on Online Social Networks" Entropy 21, no. 8: 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21080772