Ray–Wave Correspondence in Anisotropic Mesoscopic Billiards

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Trajectory Tracing in Electronic and Optical Anisotropic Billiards

2.1. Anisotropic Bilayer Graphene Billiards

2.2. Anisotropy and Polarization

2.3. From the Index Ellipsoid to the Dispersion Relation in Uniaxial Optical Billiards

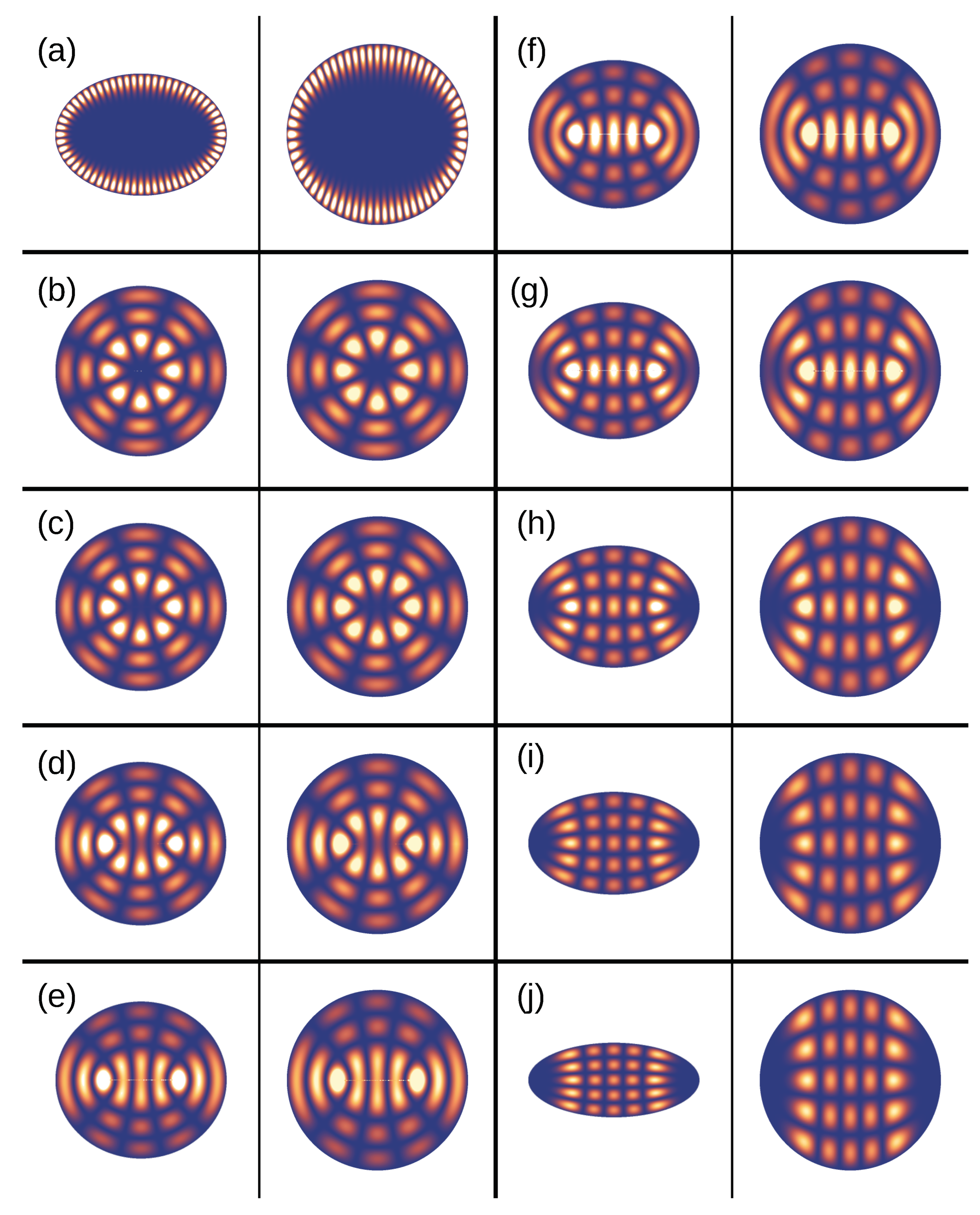

3. Wave and Transformation Optics for the Birefringent Disk

4. Discussion: Ray–Particle-Wave Correspondence for Optical and Electronic Systems

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryder, L.H. Quantum Field Theory, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Noether, E. Invariante Variationsprobleme. Nachrichten Ges. Wiss. Göttingen Math.-Phys. Kl. 1918, 1918, 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Akkermans, E.; Montambaux, G. Mesoscopic Physics of Electrons and Photons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckmann, H.J. Quantum Chaos: An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, K.; Harayama, T. Quantum Chaos and Quantum Dots; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahala, K. Optical Microcavities; World Scientific: Singapore, 2004; Available online: https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/5485 (accessed on 12 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.F.; Zou, C.L.; Li, Y.; Dong, C.H.; Han, Z.F.; Gong, Q. Asymmetric Resonant Cavities and Their Applications in Optics and Photonics: A Review. Front. Optoelectron. China 2010, 3, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E.; Koshino, M. The Electronic Properties of Bilayer Graphene. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013, 76, 056503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E.; Abergel, D.S.; Fal’ko, V.I. The Low Energy Electronic Band Structure of Bilayer Graphene. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2007, 148, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, L.; Knothe, A.; Hentschel, M. Gate-tunable regular and chaotic electron dynamics in ballistic bilayer graphene cavities. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 205404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanic, M.; Toklikishvili, Z.; Mishra, S.; Trybus, M.; Chotorlishvili, L. Magnetoelectric fractals, Magnetoelectric parametric resonance and Hopf bifurcation. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2024, 467, 134257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdin, D.; Ekonomov, N.; Gordeev, S.; Fetisov, Y. Anisotropy of magnetoelectric effects in an amorphous ferromagnet-piezoelectric heterostructure. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 521, 167530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukharaev, A.A.; Zvezdin, A.K.; Pyatakov, A.P.; Fetisov, Y.K. Straintronics: A new trend in micro- and nanoelectronics and materials science. Physics-Uspekhi 2018, 61, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchinitser, N.M.; Shalaev, V.M. Photonic metamaterials. Laser Phys. Lett. 2008, 5, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbas, A.M.; Jacob, Z.; Negro, L.D.; Engheta, N.; Boardman, A.D.; Egan, P.; Khanikaev, A.B.; Menon, V.; Ferrera, M.; Kinsey, N.; et al. Roadmap on optical metamaterials. J. Opt. 2016, 18, 093005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, U.; Philbin, T.G. Chapter 2 Transformation Optics and the Geometry of Light. In Progress in Optics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 53, pp. 69–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, I.; Cho, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, M. Designing arbitrary-shaped whispering-gallery cavities based on transformation optics. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 16320–16328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lim, J.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, I.; Cho, J.; Rim, S.; Choi, M. Birefringent whispering gallery cavities designed by linear transformation optics. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 9242–9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, K. (Ed.) Semiclassical Theory of Mesoscopic Quantum Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, M.; Richter, K. Quantum chaos in optical systems: The annular billiard. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 056207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Rim, S.; Ryu, J.W.; Kwon, T.Y.; Choi, M.; Kim, C.M. Quasiscarred Resonances in a Spiral-Shaped Microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 164102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersig, J.; Hentschel, M. Combining Directional Light Output and Ultralow Loss in Deformed Microdisks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 033901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, A.; Bittner, S.; Dietz, B.; Trabattoni, A.; Ulysse, C.; Romanelli, M.; Brunel, M.; Zyss, J.; Lebental, M. Waves and rays in plano-concave laser cavities: II. A semiclassical approach. Eur. J. Phys. 2017, 38, 034011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, Q.; Robnik, M. Finite time quantum-classical correspondence in quantum chaotic systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.05596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, S.; Hentschel, M.; Wiersig, J.; Sasaki, T.; Harayama, T. Ray-wave correspondence in limaçon-shaped semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 031801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrepfer, J.K.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, M.H.; Richter, K.; Hentschel, M. Dirac Fermion Optics and Directed Emission from Single- and Bilayer Graphene Cavities. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 155436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, H.G.; Just, W. Deterministc Chaos; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, L.; Knothe, A.; Hentschel, M. Steering internal and outgoing electron dynamics in bilayer graphene cavities by cavity design. New J. Phys. 2024, 26, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, B.; Teich, M. Fundamentals of Photonics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Demtröder, W. Electrodynamics and Optics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itin, Y. Dispersion relation for electromagnetic waves in anisotropic media. Phys. Lett. A 2010, 374, 1113–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazutkin, V.F. Existence of caustics for the billiard problem in a convex domain. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat. 1973, 37, 186–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopac, V.; Mrkonjić, I.; Pavin, N.; Radić, D. Chaotic dynamics of the elliptical stadium billiard in the full parameter space. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2006, 217, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, R.; McGhee, D. Partial Differential Equations; DE GRUYTER: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, R.; (TU Dresden, Germany). Private communication, 2024.

- Sun, F.; Zheng, B.; Chen, H.; Jiang, W.; Guo, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; He, S. Transformation Optics: From Classic Theory and Applications to its New Branches. Laser Photonics Rev. 2017, 11, 1700034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waalkens, H.; Wiersig, J.; Dullin, H.R. Elliptic Quantum Billiard. Ann. Phys. 1997, 260, 50–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, N. Theory and Application of Mathieu Functions; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Seemann, L.; Lukin, J.; Häßler, M.; Gemming, S.; Hentschel, M. Complex dynamics in circular and deformed bilayer graphene inspired billiards with anisotropy and strain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.07934. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hentschel, M.; Schlötzer, S.; Seemann, L. Ray–Wave Correspondence in Anisotropic Mesoscopic Billiards. Entropy 2025, 27, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27020132

Hentschel M, Schlötzer S, Seemann L. Ray–Wave Correspondence in Anisotropic Mesoscopic Billiards. Entropy. 2025; 27(2):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27020132

Chicago/Turabian StyleHentschel, Martina, Samuel Schlötzer, and Lukas Seemann. 2025. "Ray–Wave Correspondence in Anisotropic Mesoscopic Billiards" Entropy 27, no. 2: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27020132

APA StyleHentschel, M., Schlötzer, S., & Seemann, L. (2025). Ray–Wave Correspondence in Anisotropic Mesoscopic Billiards. Entropy, 27(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27020132