Thoughtseeds: A Hierarchical and Agentic Framework for Investigating Thought Dynamics in Meditative States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“The most intelligent minds are those that can entertain an idea without necessarily believing in it”.—Aristotle

1.1. Embodied Cognition: An Evolutionary and Variational Free Energy Perspective

1.2. Neuronal Packets (NPs) Under the Free Energy Principle

2. Introduction: Thoughtseeds Framework

2.1. Thoughtseeds Hypothesis

- The Intrinsic Ignition Framework [48], which explores spontaneous neural events driving cognition.

2.2. Introducing the Thoughtseeds Framework

- Knowledge domains (KDs): Organized units of knowledge within the brain that serve as the structural basis for thought (as a thoughtseed can be associated with specific knowledge structures, which function as its core attractor, along with secondary attractors that can form nested hierarchies across scales, as discussed in Figure 2B).

- Thoughtseeds: Attentional agents that interact within a Thoughtseed Network, enabling the framework to model the emergence, evolution, and shifting of thoughts—particularly during meditation and mind-wandering. Thoughtseeds operate within the Global Workspace, where a dominant thoughtseed emerges through a winner-takes-all dynamic.

- Meta-cognition: It monitors the Thoughtseed Network (and the Global Workspace), aligning the sentient being with its current intentionality, goals, and policies. At the top level of the nested hierarchy, it acts as an irreducible Markov blanket [22,50,51], separating its internal processes from the lower-level cognitive dynamics, which are themselves separated from external influences by the agent-level Markov blanket.

2.3. Knowledge Domains (KDs)

- Procedural KDs: These domains encode learned skills, motor control, and sensorimotor processes, guiding automatic behaviors without requiring conscious thought. For instance, riding a bicycle relies on a procedural KD, which is reflected in the influence of the active states on the environment.

- Declarative KDs: These domains store and retrieve explicit knowledge, such as facts, events, and conscious memories, which recent studies suggest may be organized through grid-like coding mechanisms [30], providing the foundation for abstract reasoning and conscious content in the Global Workspace.

2.4. Thoughtseeds Network

2.4.1. Thoughtseed States

Unmanifested State

Manifested State

- Inactive: The thoughtseed is present within the stabilized KD but does not actively influence conscious processes. It exists as a stable neural pattern that is primed for potential activation.

- Active: The thoughtseed engages in cognitive processing (part of the active thoughtseeds pool), contributing to perception and action, though it does not yet dominate the Global Workspace.

Dominant State (Activated/Spiking State)

2.4.2. Thoughtseed Definition

2.5. Meta-Cognition

- Attentional Precision: By modulating the precision of specific thoughtseeds, meta-cognition enhances or suppresses sensitivity to sensory evidence, prioritizing those most relevant for conscious access [70]. This process, shown as blue arrows from agent-level policies/intentions to the Thoughtseed Network (especially the dominant thoughtseed), sharpens perception based on current goals and context.

- Meta-Awareness: This mechanism detects shifts in behavior that do not correspond to global policies and triggers corrective actions of potential actions within the Thoughtseed Network [71]. Feedback loops (red arrows) enable the system to reflect on its strategies and adapt dynamically.

3. Applying Thoughtseeds Framework to Focused Attention Meditation Simulation

3.1. Overview

- State-dependent awareness levels that modulate thoughtseed interactions;

- Probabilistic detection mechanisms for mind-wandering that improve with expertise;

- Regulatory interventions that implement attentional control processes.

3.2. Meditative States and Empirical Grounding

3.3. Learning Framework: Rule-Based Optimization

3.3.1. Mathematical Framework for Learning

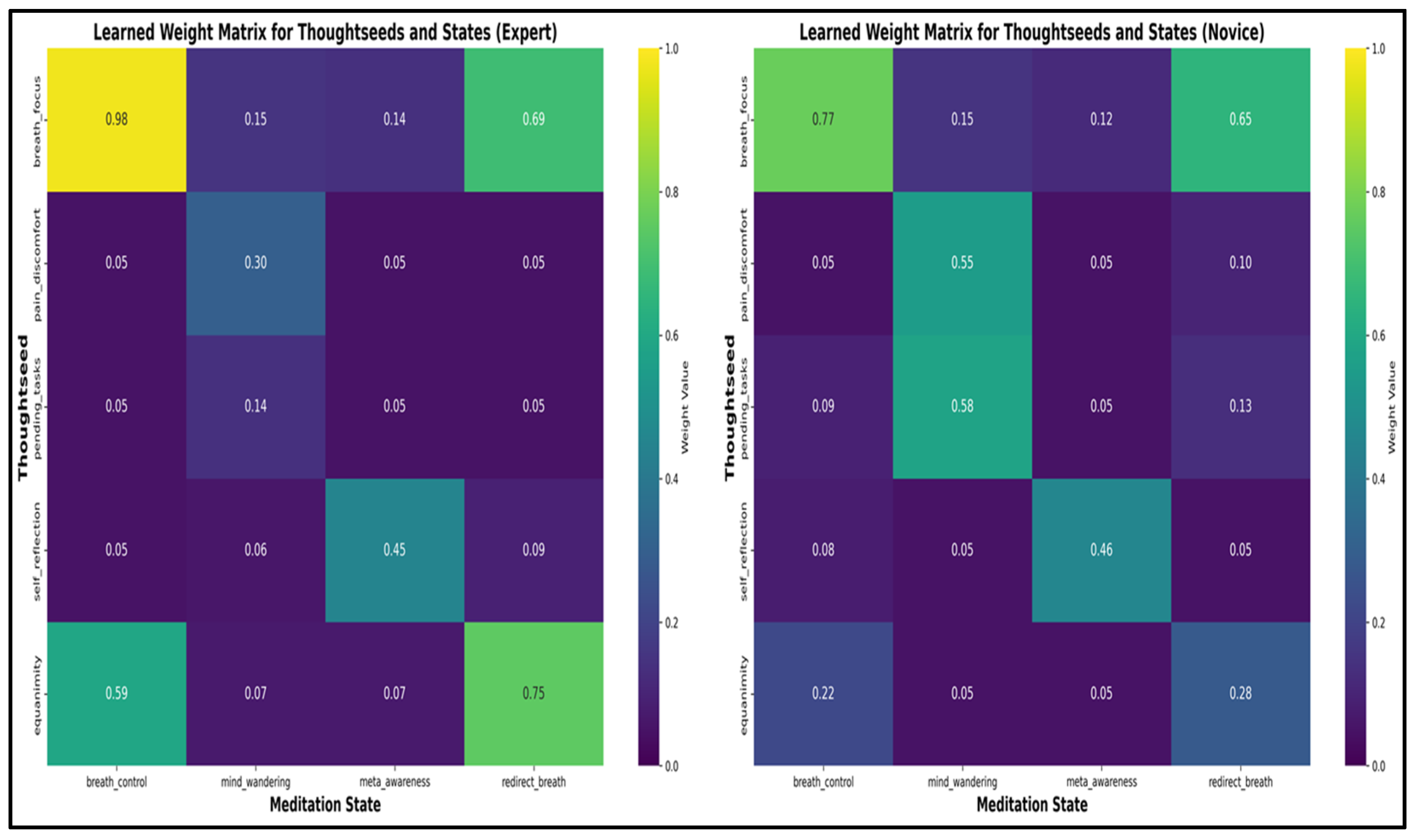

Attractor-Based Weight Matrix Construction

Nonlinear Thoughtseed Activation Dynamics

Meta-Awareness Regulation with State-Dependent Dynamics

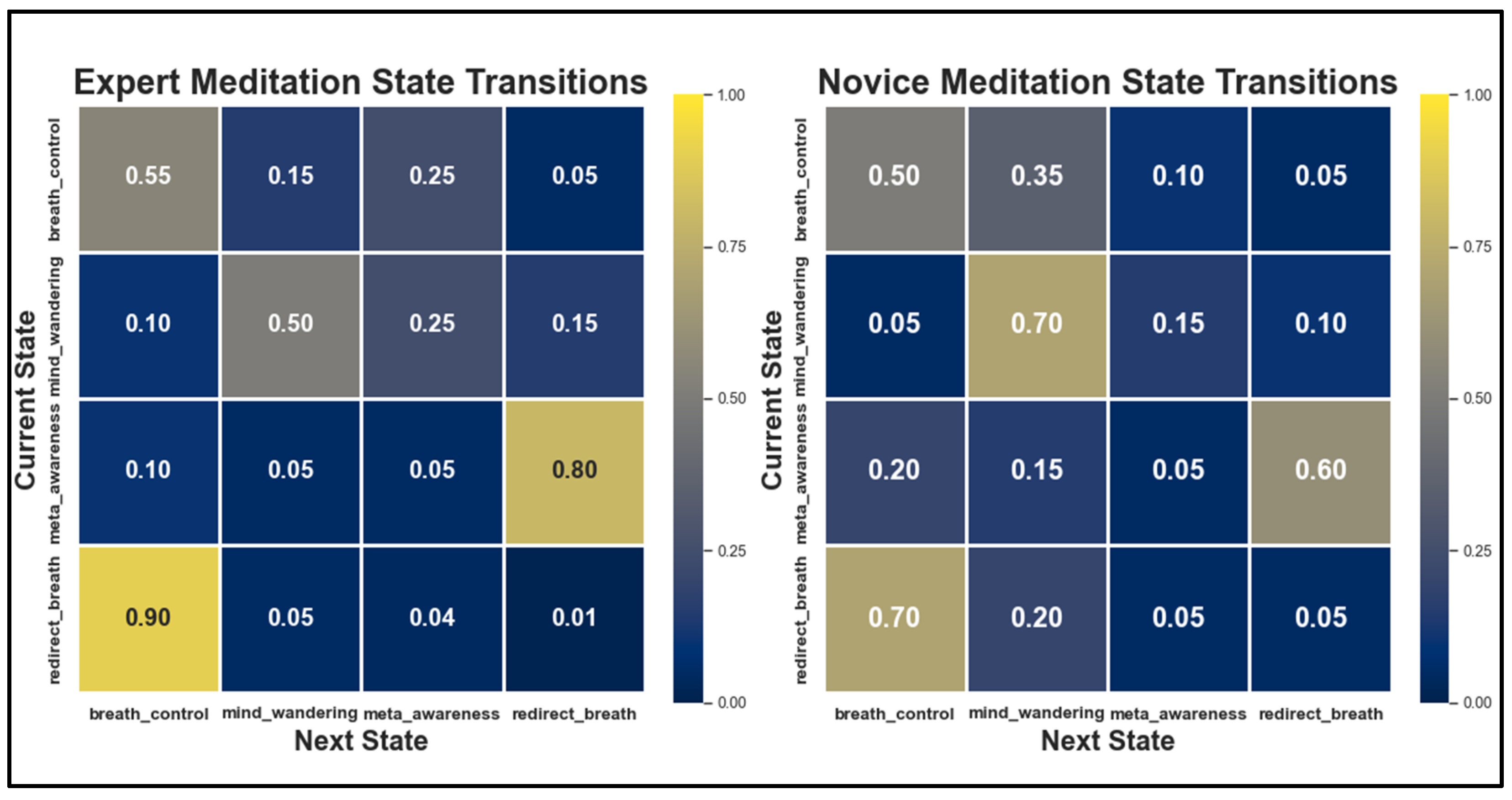

Statistical Learning of Transition Patterns

Threshold-Based State Transitions

- Natural transition: Activation pattern exceeds threshold (captured in transition_activations);

- Forced transition: Dwell time limit reached without natural transition.

3.3.2. Learning Results

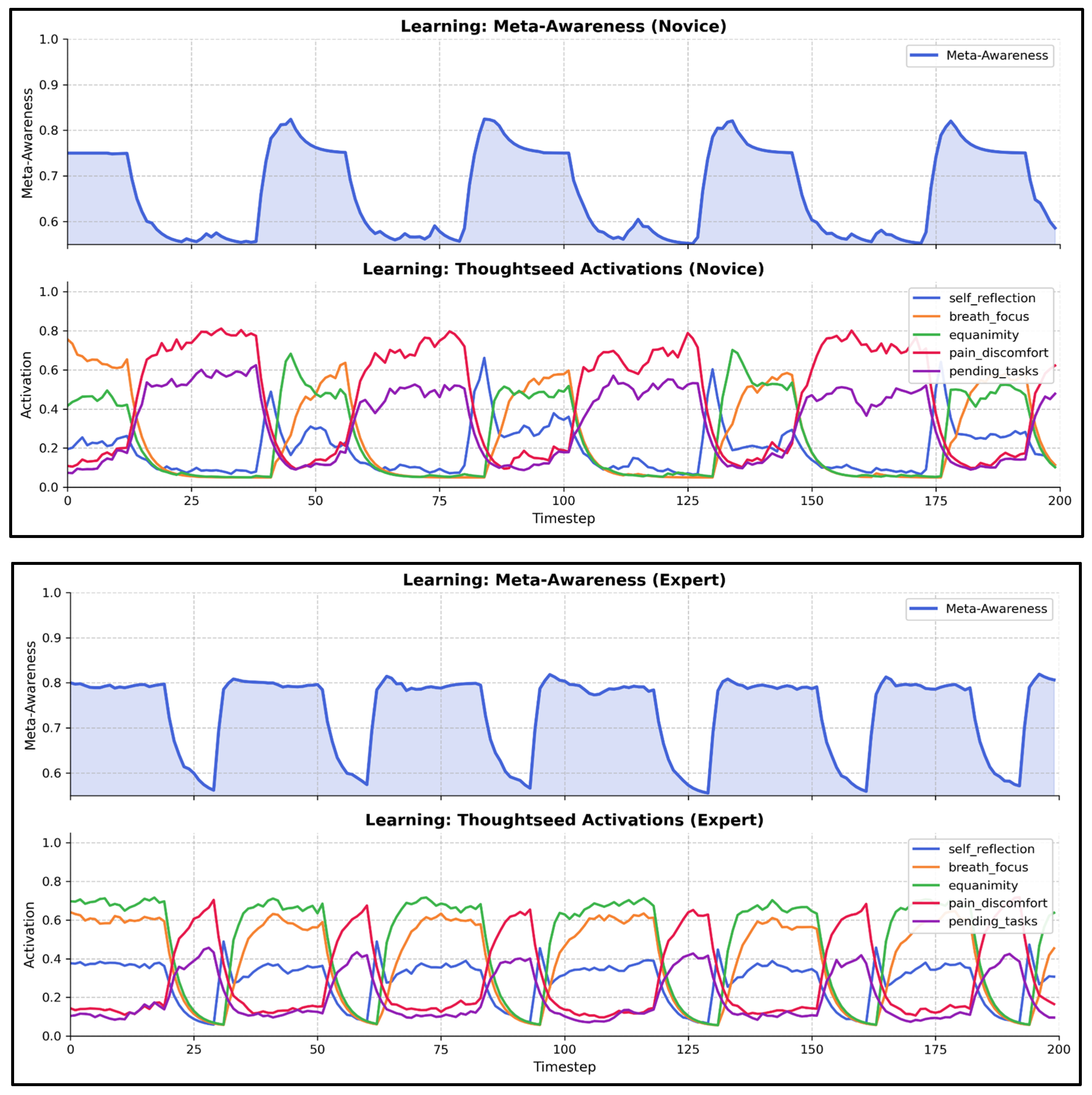

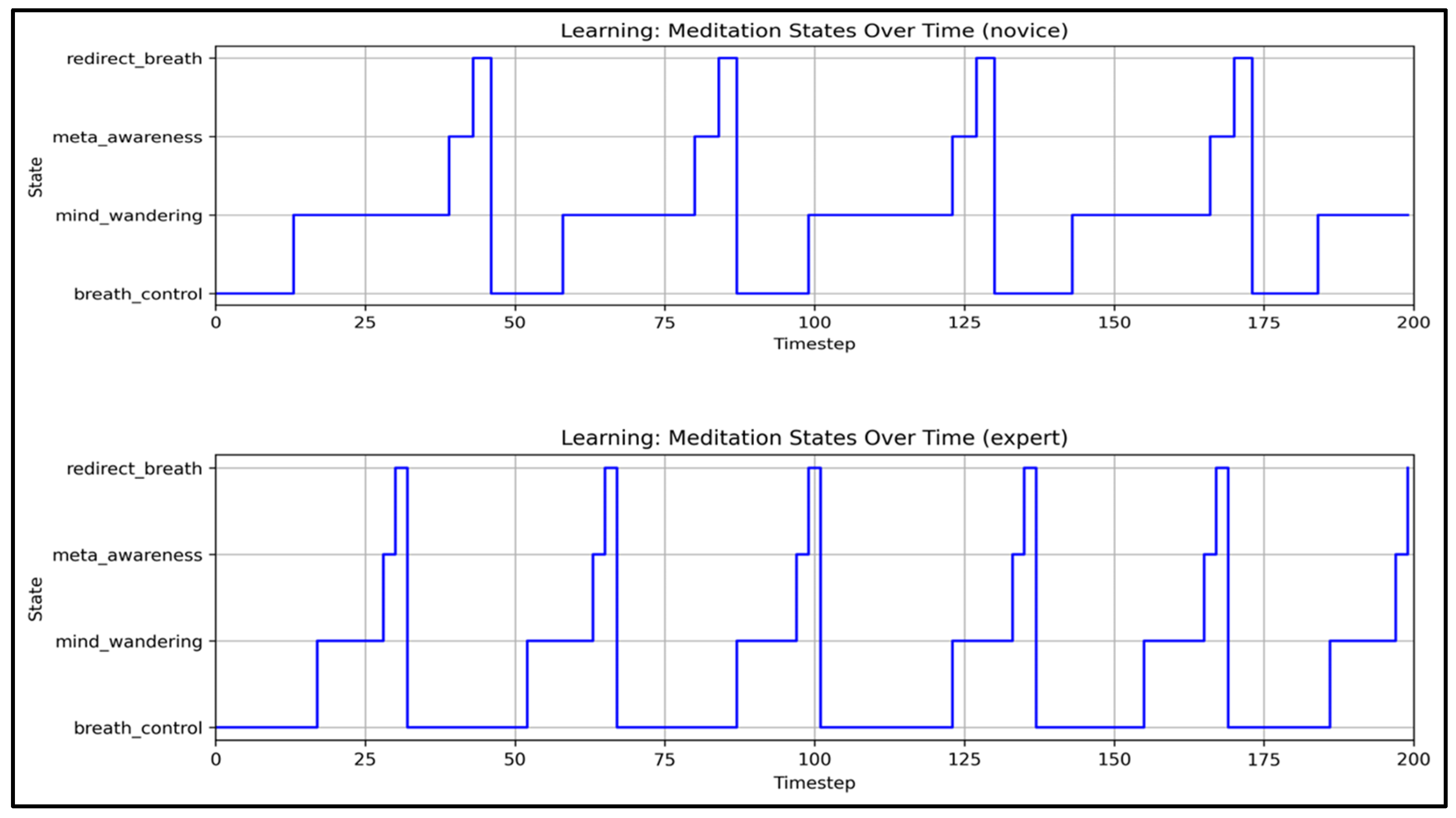

Emergent Patterns and Experience-Dependent Variations

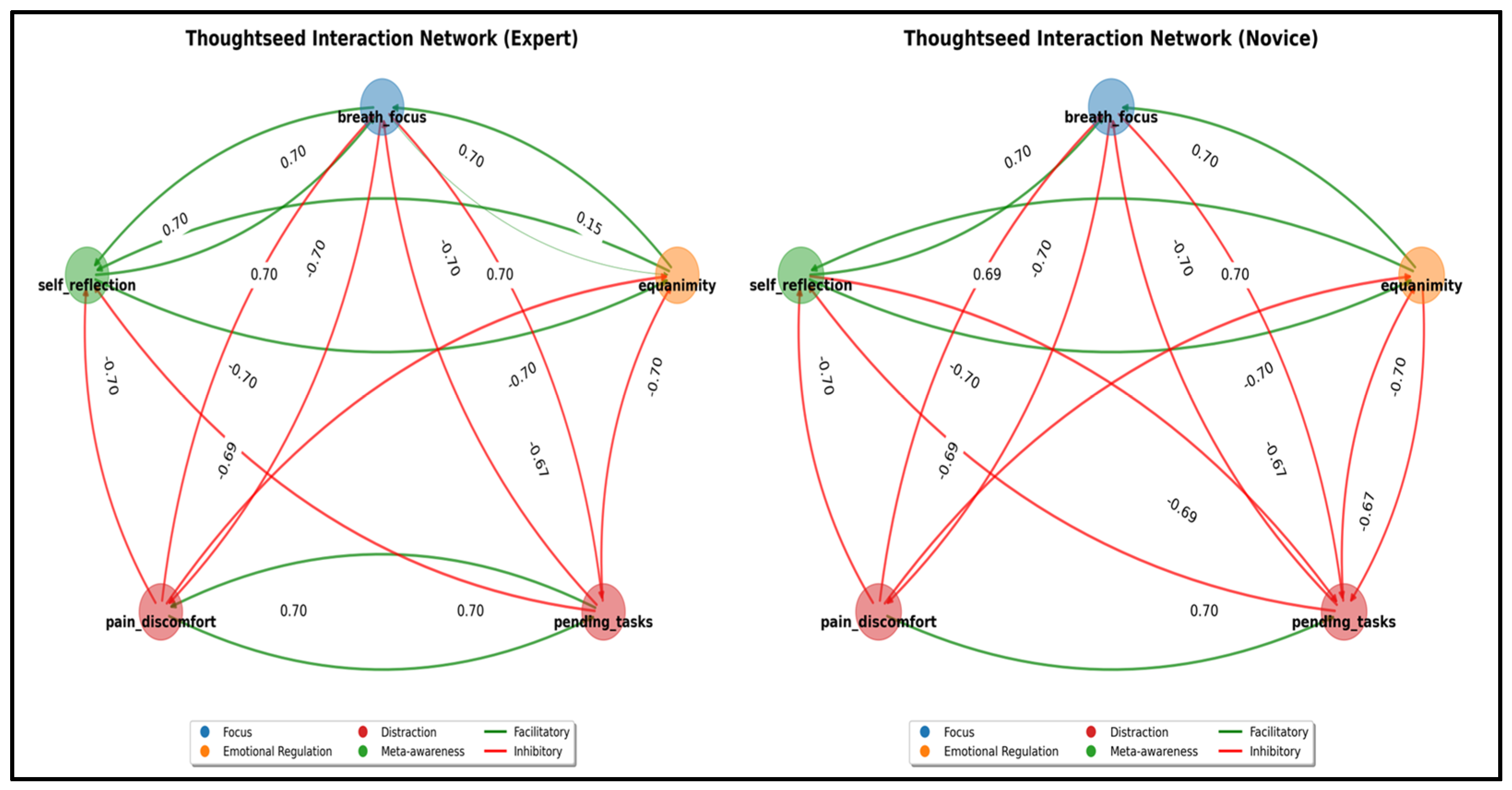

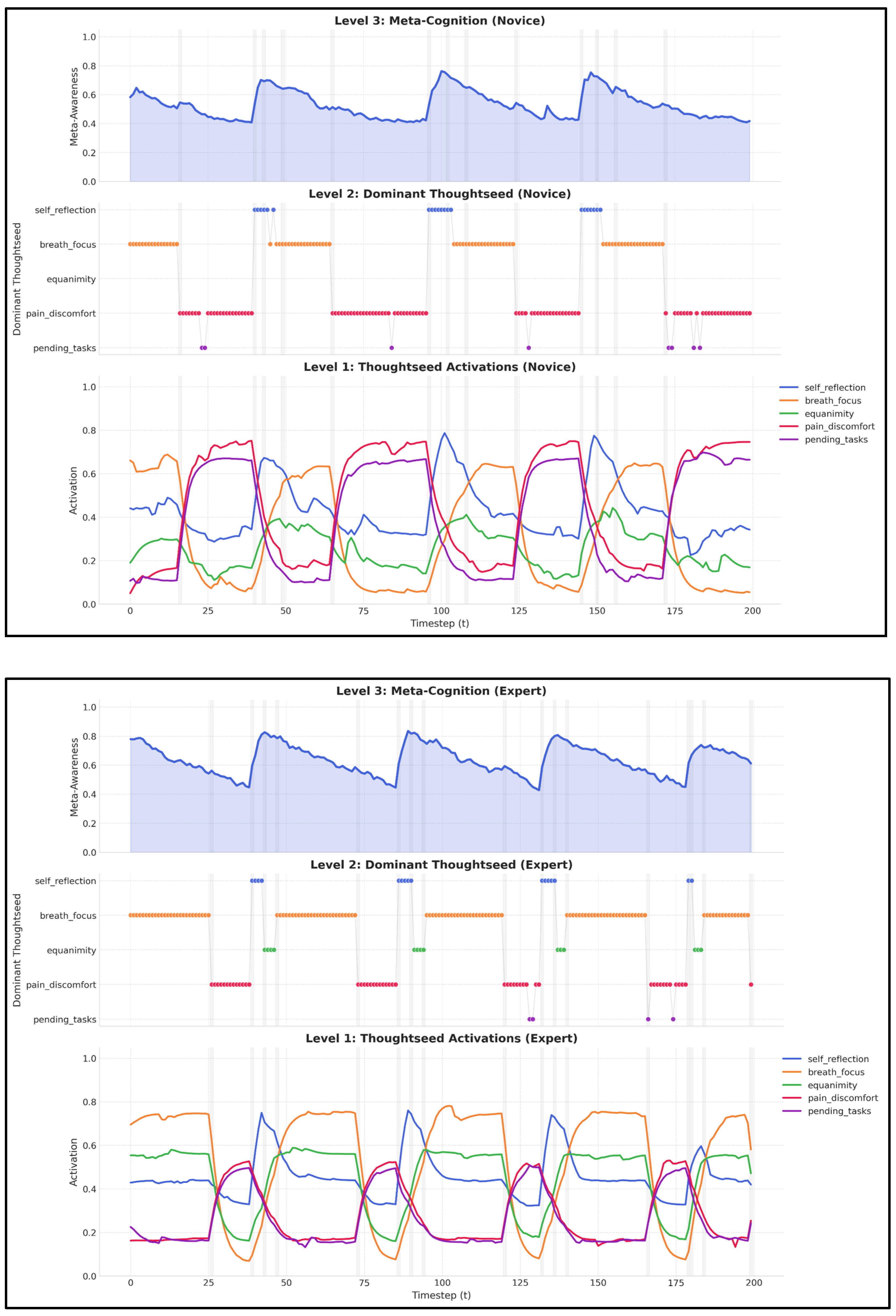

- Attention Stabilization: Experts maintain breath_focus activation during breath_control periods within a stable range of (0.50–0.60) with minimal fluctuations. In contrast, novices exhibit greater variability (0.30–0.50), alongside frequent intrusions from distracting thoughtseeds (e.g., pain_discomfort, pending_tasks), indicative of weaker attentional control [36,38].

- State Transition Efficiency: Experts demonstrate shorter mind_wandering episodes (8–12 s vs. 20–30 s for novices). They also recover more efficiently through meta_awareness and redirection states, reflecting enhanced self-monitoring and the ability to redirect focus. These patterns align with EEG findings showing reduced default mode network activity in experienced meditators [38,91].

- Meta-Awareness Dynamics: Experts maintain higher meta-awareness levels (0.75–0.9) with less variance than novices (0.6–0.8, with greater fluctuation), aligning with neuroimaging evidence of enhanced prefrontal monitoring in experienced meditators [36].

Alignment with Computational Models

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Thoughtseed Interaction Network: The Foundation of Emergent Dynamics

4.2. Multi-Scale Dynamical System for Meditation Simulation

4.2.1. Individual Thoughtseed Dynamics

4.2.2. Thoughtseed Network Dynamics

4.2.3. Emergent State Transition Dynamics

4.2.4. Dominant Thoughtseed Dynamics in the Hierarchical Framework

4.3. Results Summary

5. Discussion

5.1. Thoughtseeds and Broadcasting Dynamics Within the Global Workspace

5.2. Towards a General Theory of Embodied Cognition

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5.4. Key Limitations

5.4.1. Metastability of Thoughtseeds

5.4.2. Hierarchical Complexity

5.4.3. Individual Variability

5.5. Future Directions

5.5.1. Computational Modeling

5.5.2. Computational Modeling of Diverse Meditation Paradigms

5.5.3. Cognitive Development

5.5.4. Clinical Applications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind, Revised Edition: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noë, A. Action in Perception; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Futuyma, D.J. Evolutionary Biology. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 500–501. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J.M. A New Factor in Evolution. Am. Nat. 1896, 30, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species; John Murray: London, UK, 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J.L.; Larsen, C.S. The Nurture of Nature: Genetics, Epigenetics, and Environment in Human Biohistory. Am. Hist. Rev. 2014, 119, 1500–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.; Richerson, P.J. Culture and the Evolutionary Process; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Laland, K.N.; Odling-Smee, J.; Feldman, M.W. Niche Construction, Biological Evolution, and Cultural Change. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000, 23, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odling-Smee, F.J.; Laland, K.N.; Feldman, M.W. Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Ao, P. Free Energy, Value, and Attractors. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012, 2012, 937860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolis, G.; Prigogine, I. Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Conant, R.C.; Ross Ashby, W.R. Every Good Regulator of a System Must Be a Model of That System. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 1970, 1, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J. The Free Energy Principle: A Unified Approach to Biological Systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2010, 366, 2257–2268. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Kilner, J.; Frith, C. A Free Energy Formulation of Active Inference. Front. Comp. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K. Affordance and Active Inference. In Affordances in Everyday Life: A Multidisciplinary Collection of Essays; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Parr, T.; De Vries, P. The Graphical Brain: A Framework for Understanding Brain Function. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K.; Heins, C.; Verbelen, T.; Da Costa, L.; Salvatori, T.; Markovic, D.; Tschantz, A.; Koudahl, M.; Buckley, C.; Parr, T. From Pixels to Planning: Scale-Free Active Inference. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.20292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, P.B.; Friston, K.J.; Ramstead, M.J.D.; Ploeger, A.; Hohwy, J. The Hierarchically Mechanistic Mind: An Evolutionary Systems Theory of the Human Brain, Cognition, and Behavior. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 19, 1319–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporns, O.; Betzel, R.F. Modular Brain Networks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hipólito, I.; Ramstead, M.J.D.; Convertino, L.; Bhat, A.; Friston, K.; Parr, T. Markov Blankets in the Brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 125, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, R.J.; Martin, K.A. A Functional Microcircuit for Cat Visual Cortex. J. Physiol. 1991, 440, 735–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountcastle, V.B. The Columnar Organization of the Neocortex. Brain 1997, 120, 701–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartz, S.R.; Sejnowski, T.J. The Neural Basis of Cognitive Development: A Constructivist Manifesto. Behav. Brain Sci. 1997, 20, 537–556; discussion 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, S. A Vision of the Brain; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo, J.J.; Zoccolan, D.; Rust, N.C. How Does the Brain Solve Visual Object Recognition? Neuron 2012, 73, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, N.T.; Ercsey-Ravasz, M.M.; Ribeiro Gomes, A.R.; Lamy, C.; Magrou, L.; Vezoli, J.; Misery, P.; Falchier, A.; Quilodran, R.; Gariel, M.A.; et al. Weighted and Directed Interareal Connectivity Matrix for Macaque Cerebral Cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebb, D.O. The Organization of Behavior; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu, A.O.; O’Reilly, J.X.; Behrens, T.E.J. Organizing Conceptual Knowledge in Humans with a Gridlike Code. Science 2016, 352, 1464–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josselyn, S.A.; Tonegawa, S. Memory Engrams: Recalling the past and Imagining the Future. Science 2020, 367, eaaw4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufik, Y.M.; Friston, K. Life and Understanding: The Origins of ‘Understanding’ in Self-Organizing Nervous Systems. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, E.R.; Razi, A.; Parr, T.; Kirchhoff, M.; Friston, K. On Markov Blankets and Hierarchical Self-Organisation. J. Theor. Biol. 2020, 486, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramstead, M.J.D.; Hesp, C.; Tschantz, A.; Smith, R.; Constant, A.; Friston, K. Neural and Phenotypic Representation Under the Free-Energy Principle. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 120, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufik, Y.M. The Understanding Capacity and Information Dynamics in the Human Brain. Entropy 2019, 21, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.; Slagter, H.A.; Dunne, J.D.; Davidson, R.J. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.; Jha, A.P.; Dunne, J.D.; Saron, C.D. Investigating the Phenomenological Matrix of Mindfulness-Related Practices from a Neurocognitive Perspective. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 632–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenkamp, W.; Barsalou, L.W. Effects of Meditation Experience on Functional Connectivity of Distributed Brain Networks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Brandmeyer, T. Meditation and the Wandering Mind: A Theoretical Framework of Underlying Neurocognitive Mechanisms. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkonen, R.E.; Slagter, H.A. From Many to (n)one: Meditation and the Plasticity of the Predictive Mind. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.J. Neurophenomenology: A Methodological Remedy for the Hard Problem. J. Conscious. Stud. 1996, 3, 330–349. [Google Scholar]

- Metzinger, T. Minimal Phenomenal Experience: Meditation, Tonic Alertness, and the Phenomenology of “Pure” Consciousness. Philos. Mind Sci. 2020, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, T.J.; Windt, J.M.; Brown, L.; Carter, O.; Van Dam, N.T. Subjective Experiences of Committed Meditators Across Practices Aiming for Contentless States. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 1457–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S. Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts; Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene, S.; Changeux, J.-P. Experimental and Theoretical Approaches to Conscious Processing. Neuron 2011, 70, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baars, B.J.; Geld, N.; Kozma, R. Global Workspace Theory (GWT) and Prefrontal Cortex: Recent Developments. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashour, G.A.; Roelfsema, P.; Changeux, J.P.; Dehaene, S. Conscious Processing and the Global Neuronal Workspace Hypothesis. Neuron 2020, 105, 776–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M.L. Novel Intrinsic Ignition Method Measuring Local-Global Integration Characterizes Wakefulness and Deep Sleep. eNeuro 2017, 4, ENEURO.0106-17.2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajko, S.; Zorn, J.; Daumail, L.; Chetelat, G.; Margulies, D.S.; Lutz, A. Exploring the embodied mind: Functional connectome fingerprinting of meditation expertise. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 2024, 4, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, T.; Da Costa, L.; Friston, K. Markov blankets, information geometry and stochastic thermodynamics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2019, 378, 20190159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstead, M.J.; Albarracin, A.M.; Kiefer, A.; Klein, B.; Fields, C.; Friston, K.; Safron, A. The Inner Screen Model of Consciousness: Applying the Free Energy Principle Directly to the Study of Conscious Experience. Neurosci. Conscious. 2023, 2023, niac013. [Google Scholar]

- Pisarchik, A.N.; Serrano, N.P.; Jaimes-Reátegui, R. Brain Connectivity Hypergraphs. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th Scientific School Dynamics of Complex Networks and Their Applications (DCNA), Kaliningrad, Russia, 19–21 September 2024; pp. 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-López, G.; Chen, Y.; Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M.L.; Zhou, C. Functional complexity emerging from anatomical constraints in the brain: The significance of network modularity and rich-clubs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. Understanding Brain Networks and Brain Organization. Phys. Life Rev. 2014, 11, 400–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, E.R.; Isomura, T.; Parr, T.; Friston, K. The Emergence of Synchrony in Networks of Mutually Inferring Neurons. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelfsema, P.R. Solving the Binding Problem: Assemblies Form When Neurons Enhance Their Firing Rate-They Don’t Need to Oscillate or Synchronize. Neuron 2023, 111, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattisapu, C.; Verbelen, T.; Pitliya, R.J.; Kiefer, A.B.; Albarracin, M. Free Energy in a Circumplex Model of Emotion. In Proceedings of the Active Inference: 5th International Workshop, IWAI 2024, Oxford, UK, 9–11 September 2024, Revised Selected Papers; Buckley, C.L., Cialfi, D., Lanillos, P., Pitliya, R.J., Sajid, N., Shimazaki, H., Verbelen, T., Wisse, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 2193, pp. 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, L.R. Declarative and Nondeclarative Memory: Multiple Brain Systems Supporting Learning and Memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1992, 4, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ramanathan, K.; Ning, N.; Shi, L.; Wen, C. Memory Dynamics in Attractor Networks. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2015, 2015, 191745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellamil, M.; Fox, K.C.R.; Dixon, M.L.; Pritchard, S.; Todd, R.M.; Thompson, E.; Christoff, K. Dynamics of Neural Recruitment Surrounding the Spontaneous Arising of Thoughts in Experienced Mindfulness Practitioners. NeuroImage 2016, 136, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M.I. Orienting of Attention. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1980, 32, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.K. The Cybernetic Bayesian Brain: From Interoceptive Inference to Sensorimotor Contingencies. In Open MIND; Metzinger, T.K., Windt, J.M., Eds.; MIND Group: Wuhan, China, 2015; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Safron, A.; Çatal, O.; Verbelen, T.; Pitliya, R.J. Generalized Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (G-SLAM) as Unification Framework for Natural and Artificial Intelligences: Towards Reverse Engineering the Hippocampal/Entorhinal System and Principles of High-Level Cognition. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 787659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Rigoli, F.; Ognibene, D.; Mathys, C.; Fitzgerald, T.; Pezzulo, G. Active inference and epistemic value. Cogn. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.; Heins, C.; Ueltzhöffer, K.; Da Costa, L.; Parr, T. Stochastic Chaos and Markov Blankets. Entropy 2021, 23, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Friston, K. From cognitivism to autopoiesis: Towards a computational framework for the embodied mind. Synthese 2018, 195, 2459–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Uexküll, J. A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds. In Instinctive Behavior: The Development of a Modern Concept; Original Work Published 1934; International Universities Press: Madison, CT, USA, 1957; pp. 5–80. [Google Scholar]

- Christoff, K.; Irving, Z.C.; Fox, K.C.R.; Spreng, R.N.; Andrews-Hanna, J.R. Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: A dynamic framework. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews-Hanna, J.R.; Irving, Z.C.; Fox, K.C.R.; Spreng, R.N.; Christoff, K. 13 The Neuroscience of Spontaneous Thought: An Evolving, Interdisciplinary Field. In The Oxford Handbook of Spontaneous Thought: Mind-Wandering, Creativity, and Dreaming; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of Goal-Directed and Stimulus-Driven Attention in the Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzinger, T. Phenomenal Transparency and Cognitive Self-Reference. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2003, 2, 353–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K.J.; Fagerholm, E.D.; Zarghami, T.S.; Parr, T.; Hipólito, I.; Magrou, L.; Razi, A. Parcels and Particles: Markov Blankets in the Brain. Netw. Neurosci. 2021, 5, 211–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. Life as we know it. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20130475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandved-Smith, L.; Hesp, C.; Mattout, J.; Friston, K.; Lutz, A.; Ramstead, M.J.D. Towards a Computational Phenomenology of Mental Action: Modelling Meta-awareness and Attentional Control with Deep Parametric Active Inference. Neurosci. Conscious. 2021, 2021, niab018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, M.I.; Huerta, R.; Laurent, G. Neuroscience. Transient Dynamics for Neural Processing. Science 2008, 321, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deco, G.; Jirsa, V.K. Ongoing Cortical Activity at Rest: Criticality, Multistability, and Ghost Attractors. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 3366–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vago, D.R.; Silbersweig, D.A. Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J.A.; Worhunsky, P.D.; Gray, J.R.; Tang, Y.-Y.; Weber, J.; Kober, H. Meditation Experience Is Associated with Differences in Default Mode Network Activity and Connectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20254–20259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.-Y.; Hölzel, B.K.; Posner, M.I. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.C.; Nijeboer, S.; Dixon, M.L.; Floman, J.L.; Ellamil, M.; Rumak, S.P.; Sedlmeier, P.; Christoff, K. Functional neuroanatomy of meditation: A review and meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging investigations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 65, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, A.; Hölzel, B.K.; Mulej Bratec, S.; Boucard, C.C.; Xie, X.; Wohlschläger, A.M.; Sorg, C. Mindful attention to breath regulates emotions via increased amygdala–prefrontal cortex connectivity. NeuroImage 2016, 134, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.R.A.; Schuyler, B.S.; Mumford, J.A.; Rosenkranz, M.A.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. NeuroImage 2018, 181, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.; Abdoun, O.; Bouet, R.; Zorn, J. Mindfulness meditation is related to sensory-affective uncoupling of pain in trained novice and expert practitioners. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1301–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M.L. Hierarchy of Information Processing in the Brain: A Novel ‘Intrinsic Ignition’ Framework. Neuron 2017, 94, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M.L. Metastability and Coherence in Brain Dynamics. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach, M.L.; Deco, G. Brain states and transitions: Insights from computational neuroscience. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J.; Kringelbach, M.L.; Deco, G. Functional connectivity dynamically evolves on multiple time-scales over a static structural connectome: Models and mechanisms. NeuroImage 2017, 160, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, M.; Taatgen, N.; Sackur, J.; Bastian, M. Modeling mind-wandering: A tool to better understand distraction. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Cognitive Modeling, Groningen, The Netherlands, 9–11 April 2015; pp. 237–242. Available online: https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/16871364/vanVEtal15.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Slagter, H.A.; Davidson, R.J.; Lutz, A. Mental training as a tool in the neuro-scientific study of brain and cognitive plasticity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tognoli, E.; Kelso, J.A.S. The Metastable Brain. Neuron 2014, 81, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkovich-Ohana, A.; Glicksohn, J.; Goldstein, A. Mindfulness-induced changes in gamma band activity–Implications for the default mode network, self-reference and attention. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, A.K.; Barrett, A.B.; Barnett, L. Granger Causality Analysis in Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 3293–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporns, O. Contributions and challenges for network models in cognitive neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanesco, A.P.; Denkova, E.; Jha, A.P. Self-reported mind wandering and response time variability differentiate prestimulus electroencephalogram microstate dynamics during a sustained attention task. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2021, 33, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, N.T.; van Vugt, M.K.; Vago, D.R.; Schmalzl, L.; Saron, C.D.; Olendzki, A.; Meissner, T.; Lazar, S.W.; Kerr, C.E.; Gorchov, J.; et al. Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, J.; Axmacher, N.; Haupt, S. From alpha to gamma: Electrophysiological correlates of meditation-related states of consciousness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, B.T.T.; Krienen, F.M.; Sepulcre, J.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Lashkari, D.; Hollinshead, M.; Roffman, J.L.; Smoller, J.W.; Zöllei, L.; Polimeni, J.R.; et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011, 106, 1125–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznanski, R.R. The dynamic organicity theory of consciousness: How consciousness arises from the functionality of multiscale complexity in the material brain. J. Multiscale Neurosci. 2024, 3, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safron, A. An Integrated World Modeling Theory (IWMT) of Consciousness: Combining Integrated Information and Global Neuronal Workspace Theories With the Free Energy Principle and Active Inference Framework; Toward Solving the Hard Problem and Characterizing Agentic Causation. Front. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tononi, G.; Boly, M.; Massimini, M.; Koch, C. Integrated information theory: From consciousness to its physical substrate. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehaene, S.; Al Roumi, F.; Lakretz, Y.; Planton, S.; Sablé-Meyer, M. Symbols and mental programs: A hypothesis about human singularity. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Concept | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Neuronal Packet (NP) | Based on the Free Energy Principle, a self-organizing ensemble of neurons that encodes a specific feature or aspect of the world. |

| Encapsulated Knowledge Structure | The structured knowledge content within an NP’s Markov Blanket associated with its core attractor. |

| Superordinate Ensemble (SE) | A higher-order organization emerging from the coordinated activity of multiple NPs, via a shared generative model, enabling the representation of more complex and abstract concepts. |

| Core Attractor | The most probable and stable pattern of neural activity within a manifested NP, or a higher-order SE, embodying its core functionality or the core knowledge structure. |

| Concept | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Knowledge Domain (KD) | Self-organizing units of embodied knowledge, akin to metastable brain states, encapsulating neuronal packets (NPs) or ensembles, forming the neural basis for conscious and unconscious processing. |

| Thoughtseed | Dynamic attentional agents intrinsic to a specific KD, which acts as its core attractor. It represents recurring neural patterns associated with specific concepts, percepts, or actions, competing for the attention spotlight. |

| Global Activation Threshold | A dynamic threshold shaped by attention and arousal, setting the minimum activation for thoughtseeds to enter the active pool and compete for dominance. |

| Active Thoughtseed Pool | Thoughtseeds exceeding the global activation threshold, forming a pool of candidate attentional agents competing to influence conscious content in the Global Workspace. |

| Dominant Thoughtseed | The thoughtseed with the highest activation, minimizing Expected Free Energy, which enters the Global Workspace via winner-takes-all dynamics to shape consciousness and guide attention. It currently holds the attention spotlight. |

| Meta-awareness Parameter | A meta-cognitive parameter reflecting the brain’s self-monitoring, modulating thoughtseed competition and attentional precision in the Global Workspace. |

| Attention Precision | A meta-cognitive parameter enhancing selective attention, prioritizing thoughtseeds to gain the attention spotlight, influence their dominance in the Global Workspace, and shape conscious content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kavi, P.C.; Zamora-López, G.; Friedman, D.A.; Patow, G. Thoughtseeds: A Hierarchical and Agentic Framework for Investigating Thought Dynamics in Meditative States. Entropy 2025, 27, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050459

Kavi PC, Zamora-López G, Friedman DA, Patow G. Thoughtseeds: A Hierarchical and Agentic Framework for Investigating Thought Dynamics in Meditative States. Entropy. 2025; 27(5):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050459

Chicago/Turabian StyleKavi, Prakash Chandra, Gorka Zamora-López, Daniel Ari Friedman, and Gustavo Patow. 2025. "Thoughtseeds: A Hierarchical and Agentic Framework for Investigating Thought Dynamics in Meditative States" Entropy 27, no. 5: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050459

APA StyleKavi, P. C., Zamora-López, G., Friedman, D. A., & Patow, G. (2025). Thoughtseeds: A Hierarchical and Agentic Framework for Investigating Thought Dynamics in Meditative States. Entropy, 27(5), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050459