Abstract

The advancements of magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents (MRCAs) are continuously driven by the critical needs for early detection and diagnosis of diseases, especially for cancer, because MRCAs improve diagnostic accuracy significantly. Although hydrophilic gadolinium (III) (Gd3+) complex-based MRCAs have achieved great success in clinical practice, the Gd3+-complexes have several inherent drawbacks including Gd3+ leakage and short blood circulation time, resulting in the potential long-term toxicity and narrow imaging time window, respectively. Nanotechnology offers the possibility for the development of nontoxic MRCAs with an enhanced sensitivity and advanced functionalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided synergistic therapy. Herein, we provide an overview of recent successes in the development of renal clearable MRCAs, especially nanodots (NDs, also known as ultrasmall nanoparticles (NPs)) by unique advantages such as high relaxivity, long blood circulation time, good biosafety, and multiple functionalities. It is hoped that this review can provide relatively comprehensive information on the construction of novel MRCAs with promising clinical translation.

1. Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is extensively used as a noninvasive, nonionizing, and radiation-free clinical diagnosis tool for detection and therapeutic response assessment of various diseases including cancer, because it can provide anatomical and functional information of regions-of-interest (ROI) with high spatial resolution through manipulating the resonance of magnetic nucleus (e.g., 1H) in the body via an external radiofrequency pulse magnetic field [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Although it is possible to generate high-contrast images of soft tissues for diagnosis by manipulating pulse sequences alone, MRI is able to further highlight the anatomic and pathologic features of ROI through utilized in concert with contrast agents. Magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents (MRCAs) play an extremely important role in modern radiology because the growth of contrast-enhanced MRI has been remarkable since 1988 [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Up to date, the commercially approved MRCAs and the MRCAs in clinical trial are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Typical magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents (MRCAs) clinically approved or in clinical trials.

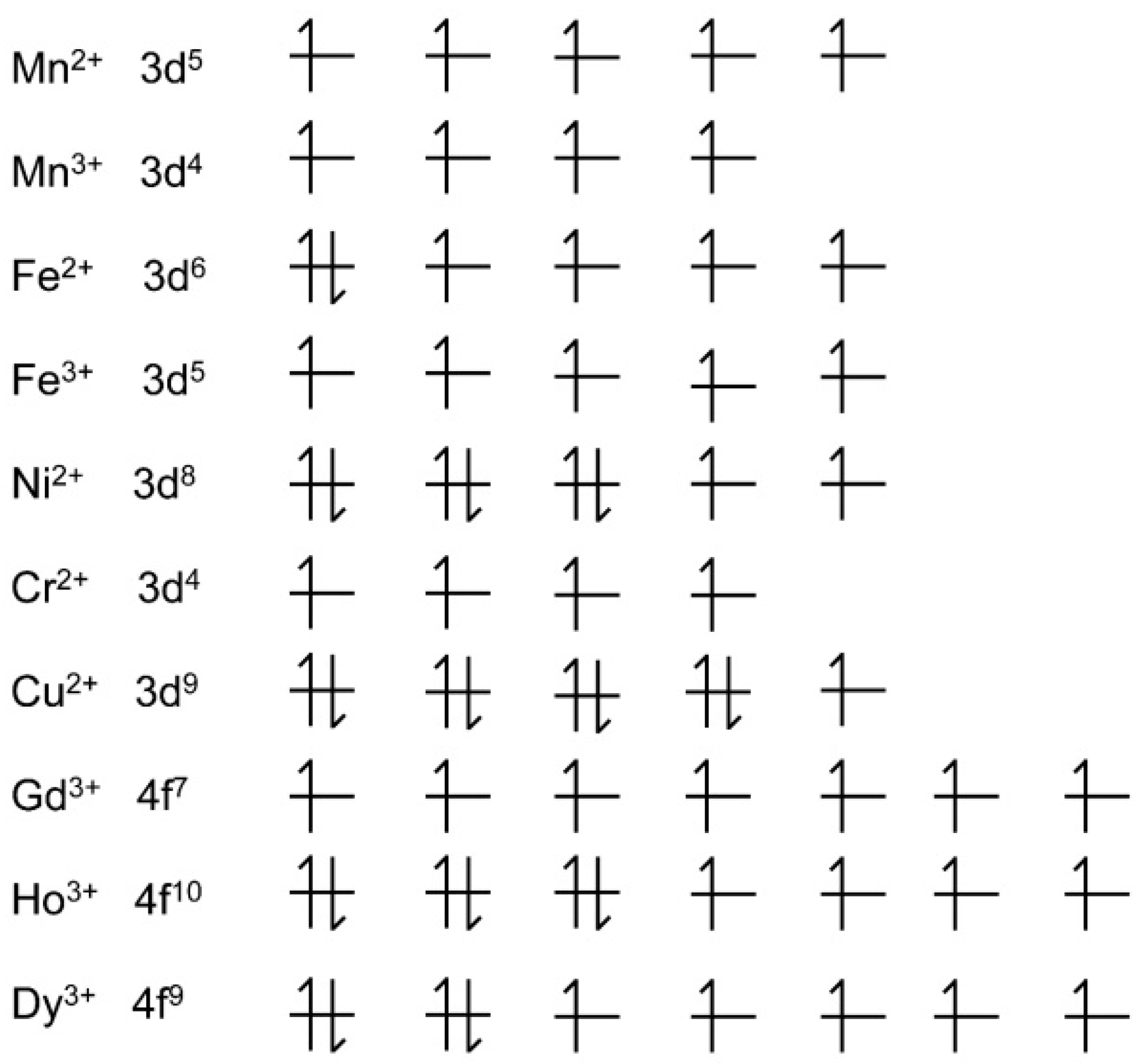

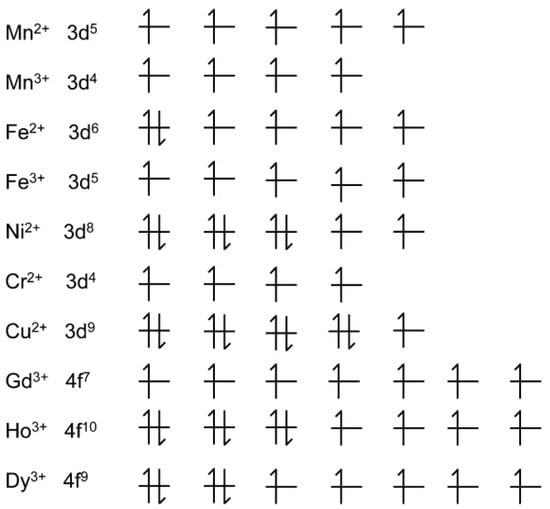

In general, there are two imaging modes of MRI, named as T1- or T2-weighted MRI, which have been employed to acquire the restored or residual magnetization by adjusting parameters in either the longitudinal direction or the transverse plane, respectively. The T1-weighted MR image shows bright signal contrast (recovered magnetization), while the T2-weighted MR image shows dark signal contrast (residual magnetization). The T1- or T2-weighted MRI can be performed in one machine by simply adjusting the acquisition sequences during the MRI process. Consequently, the MRCAs are divided into two categories based on their dominant functions in T1- or T2-weighted MRI. Paramagnetic metal nanomaterials/complexes are usually designated as T1-weighted MRCAs, which cause bright contrast in T1-weighted MR images [3,4,8,9,10]. For example, gadolinium (III) (Gd3+) has seven unpaired electrons and a long electron spin relaxation time, which can efficiently promote the longitudinal 1H relaxation. Gd3+-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (Gd-DTPA) was synthesized as the first T1-weighted MRCA and used for contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI of intracranial lesions in 1988 [8]. Superparamagnetic nanoparticles (e.g., superparamagnetic iron-oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs)) are normally used as T2-weighted MRCAs, which provide dark contrast in MR images [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The advantages and disadvantages of Gd3+- and SPION-based MRCAs have been discussed in the reviews which are published elsewhere [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. In particular, the advent of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) and bone/brain deposition has led to increased regulatory scrutiny of the safety of commercial Gd3+ chelates [9]. Figure 1 shows the typical paramagnetic cations including transition metallic cations and lanthanide cations, which are capable of enhancing contrast on MR images. The cations contain unpaired electrons in 3d electron orbitals (transition metallic cations) and/or 4f electron orbitals (lanthanide cations). In addition, several strategies have been proposed for development of T1-/T2-weighted dual-mode MRCAs, because T1-/T2-weighted dual-mode MRI can provide an accurate match of spatial and temporal imaging parameters [12]. Therefore, the accuracy and reliability of disease diagnosis can be clearly improved by synergistically enhancing both T1-/T2-weighted contrast effects.

Figure 1.

The electron subshell diagrams of typical paramagnetic cations. Generally, the larger number of unpaired electrons leads to stranger magnetic resonance (MR) contrast.

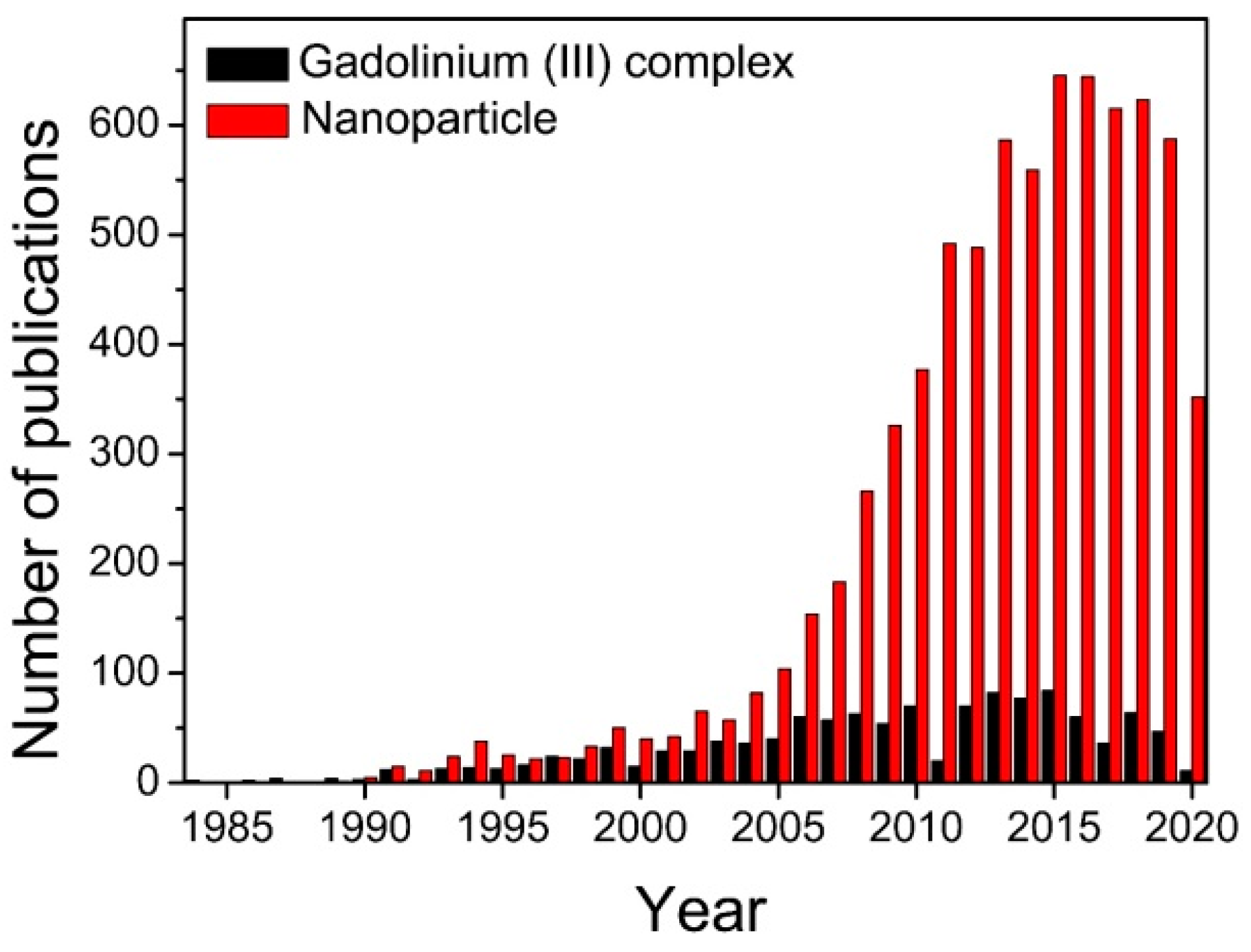

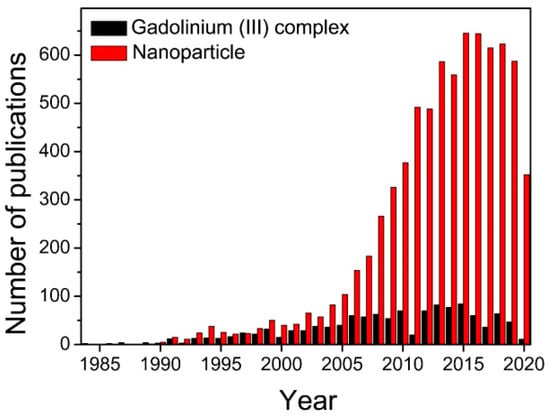

Because of their unique physiochemical and magnetic properties, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have attracted considerable attention in the construction of MRCAs with high performance during the last two decades (as shown in Figure 2), and they exhibit high potential for clinical applications in MRI-guided therapy. The synthesis, properties, functionalization strategies, and different application potentials of MNPs have been reviewed in detail in the literature published elsewhere [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. For example, the MNPs can be used as excellent MRCAs for sensitive detection of tumors because MNPs can efficiently accumulate in tumor through the leaky vasculature of tumor (also known as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect). The contrast efficacy and in vivo fate of the MNP-based MRCAs are strongly dependent on their physical and chemical features including shape, size, surface charge, surface coating material, and chemical/colloidal stability. For example, the PEGylated MNPs normally have relatively longer blood circulation time and higher colloidal/chemical stability than those of uncoated MNPs [11]. Very recently, the structure-relaxivity relationships of magnetic nanoparticles for MRI have been summarized in detail by Chen et al. [15]. Among all the characteristics of MNP, size plays a particularly important role in the biodistribution and blood circulation half-life of MNP [15,18,20]. The long blood circulation half-life of MNP can significantly increase the time window of imaging. However, the nonbiodegradable MNPs with large hydrodynamic size (more than 10 nm) exhibit high uptake in the reticuloendothelial system (RES) organs such as lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and lung, which causes slow elimination through hepatobiliary excretion [21]. The phenomenon increases the likelihood of toxicity in vivo [22], and severely hampers translating MNPs into clinical practices because the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that any imaging agent (administered into the body) should be completely metabolized/excreted from the body just after their intended medical goals such as image-guided therapy [23]. The conundrum could be sorted out by the development of renal clearable MNPs since renal elimination enables rapidly clear intravenously administered nanoparticles (NPs) from circulation to be excreted from body. Due to the pore size limit of glomerular filtration in the kidney, only the MNPs with small hydrodynamic diameter (less than 10 nm) or biodegradable ability are able to balance the long blood circulation half-life time for imaging and efficient renal elimination for biosafety. In addition, although they have similar small hydrodynamic diameters, the negatively charged or neutral NPs are more difficult to be eliminated by the kidney than their positively charged counterparts.

Figure 2.

The number of publications searching for “magnetic resonance imaging and contrast agents” plus “gadolinium (III) complex” or “nanoparticle” in the “Web of Science”. Development of nanoparticle-based MRCAs has been the hot topic of the area since 2005.

Herein, this review provides the state of the art of renal clearable composites/MNPs-based MRCAs with particular focus on several typical formats, namely Gd3+-complex-based composites and magnetic metal nanodots (MNDs), by using illustrative examples. The MNDs mean MNPs with ultrasmall hydrodynamic size (typically less than 10 nm in diameter) such as ultrasmall Gd2O3 NPs, ultrasmall NaGdF4 NPs, ultrasmall Fe2O3/Fe3O4 NPs and ultrasmall polymetallic oxide NPs. The gathered data clearly demonstrate that renal clearable composites/MNDs offer great advantages in MRI, which shows a great impact on the development of theranostic for various diseases, in particular for cancer diagnosis and treatment. In addition, we also discussed current challenges and gave an outlook on potential opportunities in the renal clearable composites/MNDs-based MRCAs.

2. Gadolinium (III)-Complex-Based Composites

Up to date, all of the MRCAs commercially available in clinic are small molecule Gd3+-complexes, which are used in about 40% of all MRI examinations (i.e., about 40 million administrations of Gd3+-complex-based MRCA) [24]. However, the small molecule Gd3+-complexes generally have short blood circulation time with a typical elimination half-life of about 1.5 h [8,9,25,26,27]. The rapid clearance characteristic of small molecule Gd3+-complex makes it difficult to conduct the time-dependent MRI studies. Conjugation of Gd3+-complexes with biodegradable materials (e.g., polymers) and/or renal clearable NDs can not only significantly prolong blood circulation of Gd3+-complexes, but also improve accumulation amount of Gd3+-complexes in solid tumors through an EPR effect [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Therefore, the Gd3+-complex-based composites enable one to provide an imaging window of a few hours before it is cleared from the body, and additionally enhance the resulting MR signal of a tumor. In particular, biodegradability or small size that ensures the complete clearance of Gd3+-complex-based composites within a relatively short time (i.e., a day) by renal elimination after diagnostic scans.

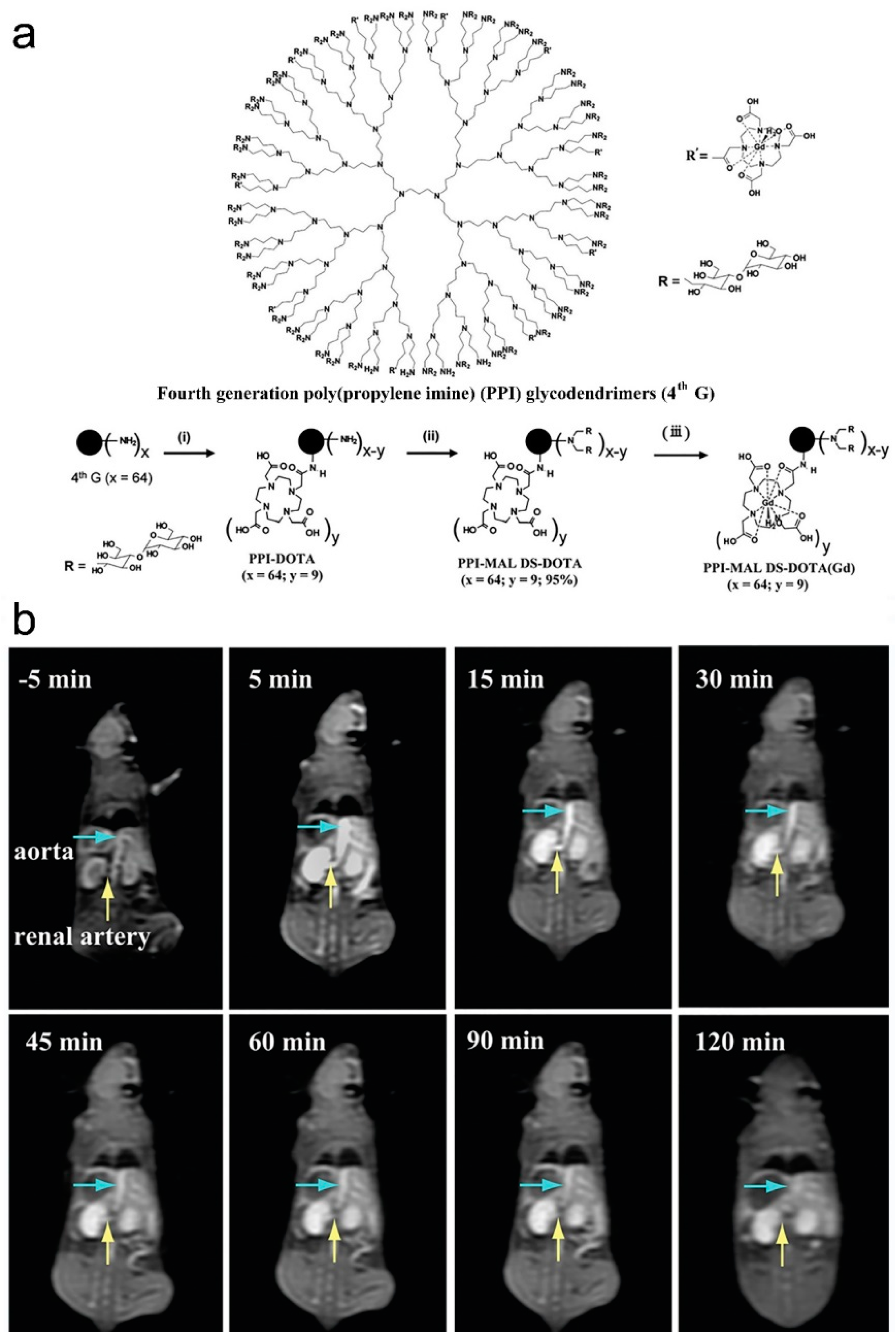

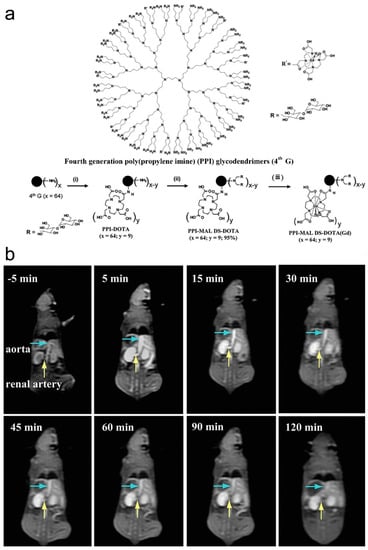

As early as 2012, Li and coauthors synthesized a poly(N-hydroxypropyl-l-glutamine)-DTPA-Gd (PHPG-DTPA-Gd) composite through conjugation of Gd-DTPA on the poly(N-hydroxypropyl-l-glutamine) (PHPG) backbone [34]. The longitudinal relaxivity (r1) of PHPG-DTPA-Gd (15.72 mM−1⋅S−1) is 3.7 times higher than that of DTPA-Gd (MagnevistT). PHPG-DTPA-Gd has excellent blood pool activity. The in vivo MRI of C6 glioblastom-bearing nude mouse exhibited significant enhancement of the tumor periphery after administration of PHPG-DTPA-Gd at a dose of 0.04 mmol Gd kg−1 via tail vein, and the mouse brain angiography was clearly delineated up to 2 h after injection of PHPG-DTPA-Gd. Degradation of PHPG-DTPA-Gd by lysosomal enzymes and hydrolysis of side chains lead to complete clearance of Gd-DTPA moieties from the body within 24 h though the renal route. Shi and coauthors synthesized a Gd-chelated poly(propylene imine) dendrimer composite (PPI-MAL DS-DOTA(Gd)) through chelation of Gd3+ with tetraazacyclododecane tetraacetic acid (DOTA) modified fourth generation poly(propylene imine) (PPI) glycodendrimers (as shown in Figure 3a) [36]. The r1 of PPI-MAL DS-DOTA(Gd) is 10.2 mM−1⋅s−1, which is 3.0 times higher than that of DOTA(Gd) (3.4 mM−1⋅s−1). The as-synthesized PPI-MAL DS-DOTA(Gd) can be used as an efficient MRCA for enhanced MRI of blood pool (aorta/renal artery, as shown in Figure 3b) and organs in vivo. The PPI-MAL DS-DOTA(Gd) exhibits good cytocompatibility and hemocompatibility, which can be metabolized and cleared out of the body at 48 h post-injection.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic illustration of the approach used to synthesize the PPI-MAL DS-DOTA(Gd), and (b) T1-weighted MR images of mouse aorta and renal artery at 5 min before injection (−5 min) and at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min post-injection of the PPI-MAL DS-DOTA(Gd) ([Gd3+] = 2 mg mL−1 in 0.2 mL saline through tail vein, adapted from Shi et al. 2016 [36], Copyright 2016 The Royal Society of Chemistry and reproduced with permission).

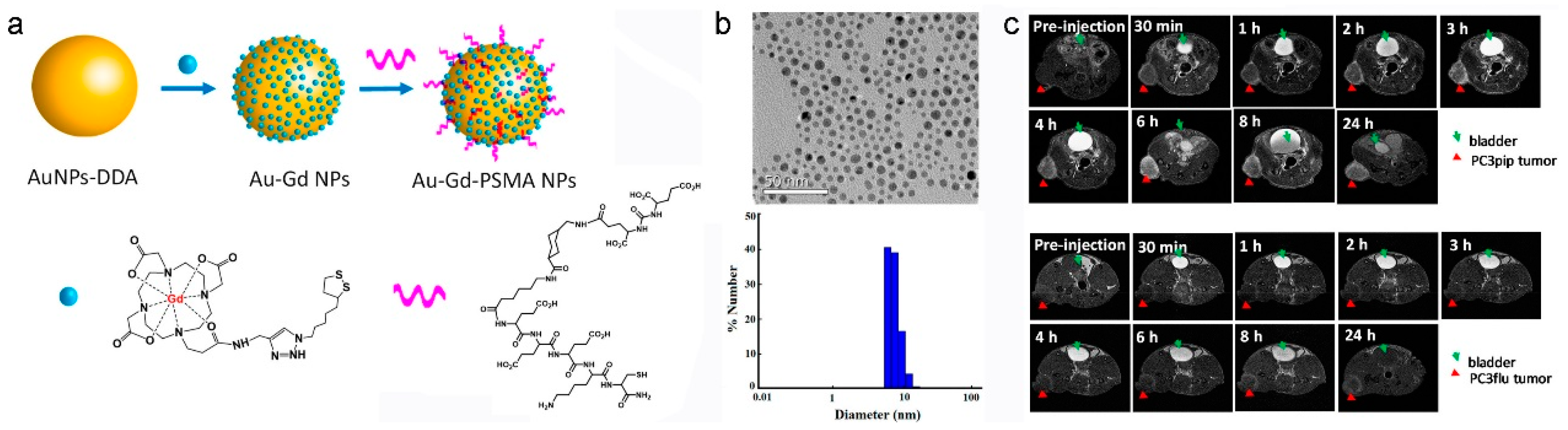

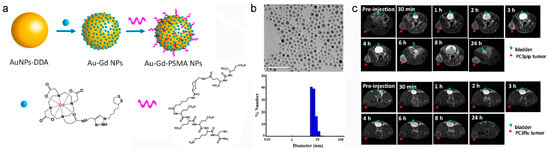

In comparison with small molecule Gd3+-complexes, Gd3+-complex-based nanocomposites provide significant advantages for contrast-enhanced MRI such as increased Gd3+ payload, prolonged blood circulation, enhanced r1 and improved uptake of Gd3+ [28,29,30]. Generally, the contrast efficiency of Gd3+-complex-based nanocomposite is affected by the structure and surface chemistry of the used nanomaterial. For example, the MRI contrast capability of Gd3+-complex-metal-organic framework (MOF) nanocomposite is strongly dependent on the size and pore shape of MOF [38]. Furthermore, the nanocomposites of Gd3+-complexes with NDs not only have relatively long blood circulation time, but also integrate the properties of both ND and Gd3+-complexes [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. The relatively easy modification property of ND offers opportunities for generation of theranostics for various biomedical applications such as targeted delivery, multimodal imaging, and imaging-guided therapy. For instance, coupling of Gd3+-complexes with optical NDs (e.g., quantum dots (QDs), noble metal nanoclusters, and carbon NDs) we can generate contrast agents for MR/fluorescence dual-mode imaging [39,42,44,45,46,47,48]. Using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as templates, Liang and Xiao synthesized Gd-DTPA functionalized gold nanoclusters (BAG), which show intense red fluorescence emission (4.9 ± 0.8 quantum yield (%)) and high r1 (9.7 mM−1⋅s−1) [47]. The in vivo MRI demonstrates that BAG circulate freely in the blood pool with negligible accumulation in the liver and spleen and can be removed from the body through renal clearance, when BAG were injected intravenously into a Kunming mouse at a dose of 0.008 mmol Gd kg−1 via the tail vein. The unique properties of BAG make it an ideal dual-mode fluorescence/MR imaging contrast agent, suggesting its potential in practical bioimaging applications in the future. Very recently, Basilion and coauthors constructed a targeted nanocomposite, Au-Gd3+-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) NPs for MRI-guided radiotherapy of prostate cancer by immobilization of the Gd3+-complex and prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) targeting ligands on the monodispersing Au NPs (as shown in Figure 4a) [50]. Because the hydrodynamic diameter of Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs is 7.8 nm, Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs enable efficient accumulation into the tumor site through the EPR effect and ligand-antigen binding, and can be excreted through the renal route. The r1 of Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs (20.6 mM−1⋅s−1) is much higher than that of free Gd3+-complexes (5.5 mM−1⋅s−1). In addition, both of the Au and Gd3+ atoms can serve as sensitizers of radiotherapy. The Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs show good tumor-targeting specificity, high MR contrast, significant in vivo radiation dose amplification, and renal clearance ability, which exhibit great potential in the clinical MR-guided radiotherapy of PSMA-positive solid tumors ((as shown in Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Au-Gd3+-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) NPs for MR-guided radiation therapy. (a) Schematic representation of Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs. (b) TEM micrograph indicates that the average core size of Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs is 5 nm, and DLS shows that the hydrodynamic diameter of Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs is 7.8 nm. (c) In vivo tumor targeting of Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs and MR imaging of PC3pip tumor-bearing mouse (up) and PC3flu tumor-bearing mouse (bottom) obtained at 7 T. PC3pip tumor cell expresses high level of PSMA, while PC3flu tumor cell expresses low level of PSMA (the mice were injected with Au-Gd3+-PSMA NPs at 60 μmol Gd3+⋅kg−1 through the tail vein, adapted from Basilion et al. 2020 [50], Copyright 2020 The American Chemical Society and reproduced with permission).

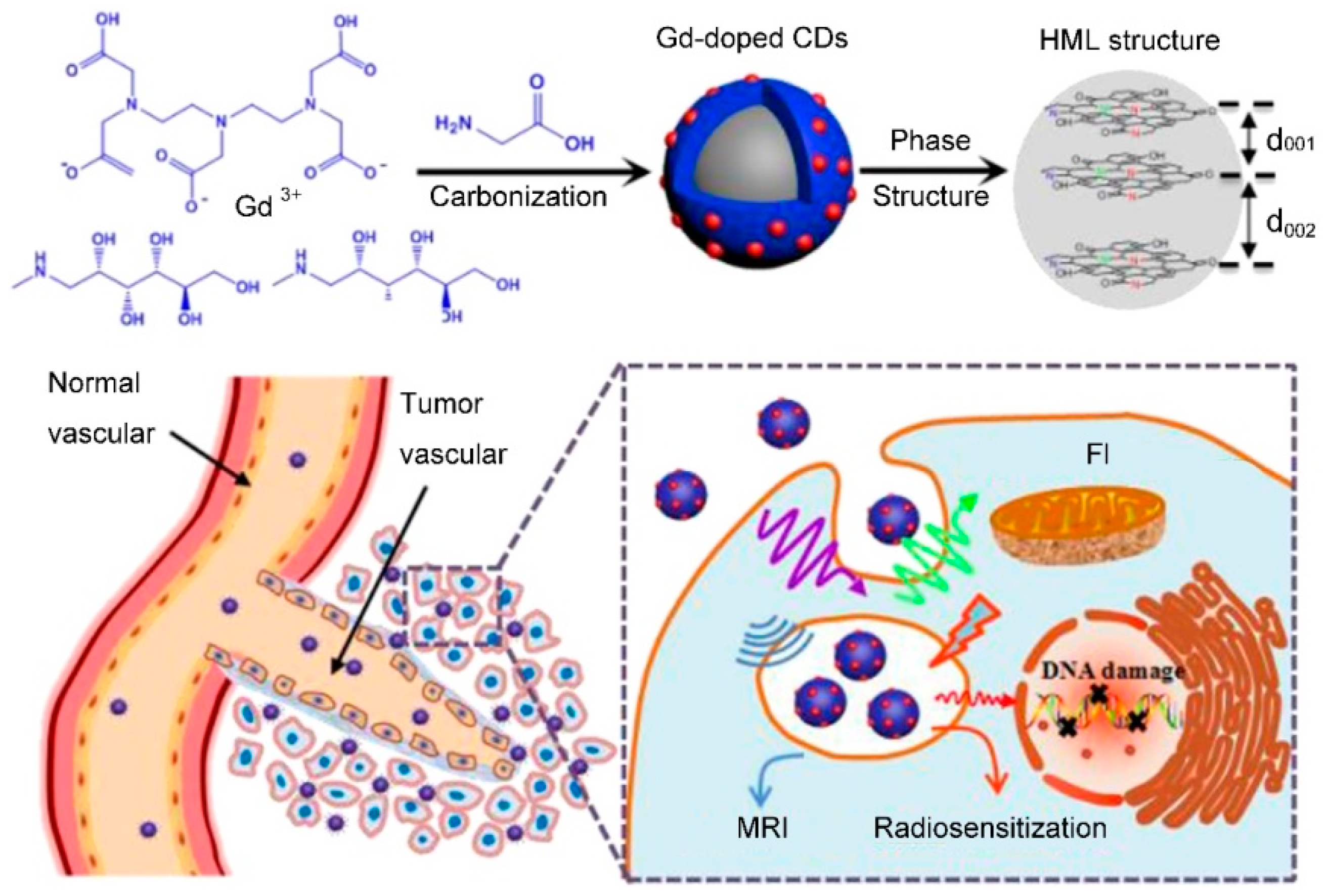

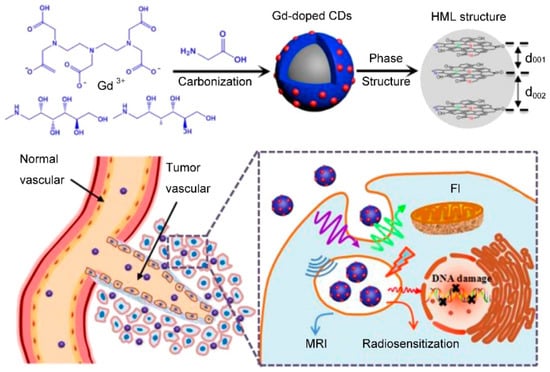

As a rising star of carbon nanomaterial, carbon quantum dots (CDs) have drawn tremendous attention because of their excellent optical property, high physicochemical stability, good biocompatibility, and the ease of surface functionalization [53,54,55,56,57]. Recently, various Gd3+-doped CDs (Gd-CD) have been synthesized for fluorescence/MR dual-mode imaging by the low temperature pyrolysis of precursors containing Gd3+ (such as Gd3+-complexes) and carbon [58,59,60,61]. Zou and coauthors reported Gd-CD-based theranostics for MRI-guided radiotherapy of a tumor (as shown in Figure 5) [58]. The Gd-CDs were synthesized through a one-pot pyrolysis of glycine and Gd-DTPA at 180 °C, which exhibited stable photoluminescence (PL) at the visible region, relatively long circulation time (~6 h), and efficient passive tumor-targeting ability. The r1 value of Gd-CDs was calculated to be 6.45 mM−1⋅s−1, which was higher than that of MagnevistT (4.05 mM−1⋅s−1) under the same conditions. An in vivo experiment demonstrated that the Gd-CDs could provide better anatomical and pathophysiologic detection of tumor and precisely positioning for MRI-guided radiotherapy, when the mice were injected intravenously with the Gd-CD solution at a dose of 10 mg Gd kg−1. In addition, the efficient renal clearance of Gd-CDs meant it was finally excreted from the body by urine.

Figure 5.

Schematic synthesis and application of Gd-doped CDs through one-pot pyrolysis of glycine and Gd-DTPA at 180 °C (adapted from Zou et al. 2017 [58], Copyright 2017 The Elsevier Ltd. and reproduced with permission).

3. Paramagnetic Metal Nanodots

During the last two decades, several MNDs have been synthesized and used as MRCAs because of their advanced imaging properties compared to small molecule Gd3+-complexes. For example, the MNDs exhibit high surface-to-volume ratios, which allow the 1H to interact with a large number of paramagnetic ions in a tiny volume, resulting in high signal-to-noise ratios at ROI. It has been demonstrated that the size of MND is directly associated with the MRI contrast capability, biodistribution, blood circulation time, and clearance rate [5,14,15,18,23,25,27]. In order to finely control over the aforementioned parameters, the as-developed MND-based MRCAs for clinical applications are highly required to be monodisperse. The hydrophilic MNDs can be directly synthesized through reactions of paramagnetic metal ionic precursors with hydrophilic coating/functionalizing agents. Although this approach is simple and direct, it is difficult to control size and uniformity of MNDs in the aqueous synthetic methods. In order to achieve narrow size distribution and low crystalline defect, most of the MNDs are synthesized by nonaqueous synthesis routes. Because of their inherent hydrophobicity, MNDs should be coated/functionalized with hydrophilic and biocompatible ligands (shells) for biomedical applications. The post-synthetic modification strategies generally involve ligand exchange with hydrophilic molecules as well as encapsulation by hydrophilic shells.

3.1. Gadolinium Nanodots

Generally, there are two protocols for the synthesis of inorganic Gd3+ NDs: (1) direct synthesis of hydrophilic Gd3+ NDs in water or polyol using a stabilizing agent which allows for crystal growth, followed by ligand exchange with a more robust stabilizing agent to improve the colloidal stability of Gd3+ NDs in complex matrixes [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81], and (2) preparation of hydrophobic Gd3+ NDs in high boiling organic solvents by the pyrolysis methods, and subsequent transfer of the hydrophobic Gd3+ NDs into aqueous phase by using a hydrophilic/amphiphilic ligand to render them water-dispersible [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

3.1.1. Gadolinium Oxide Nanodots

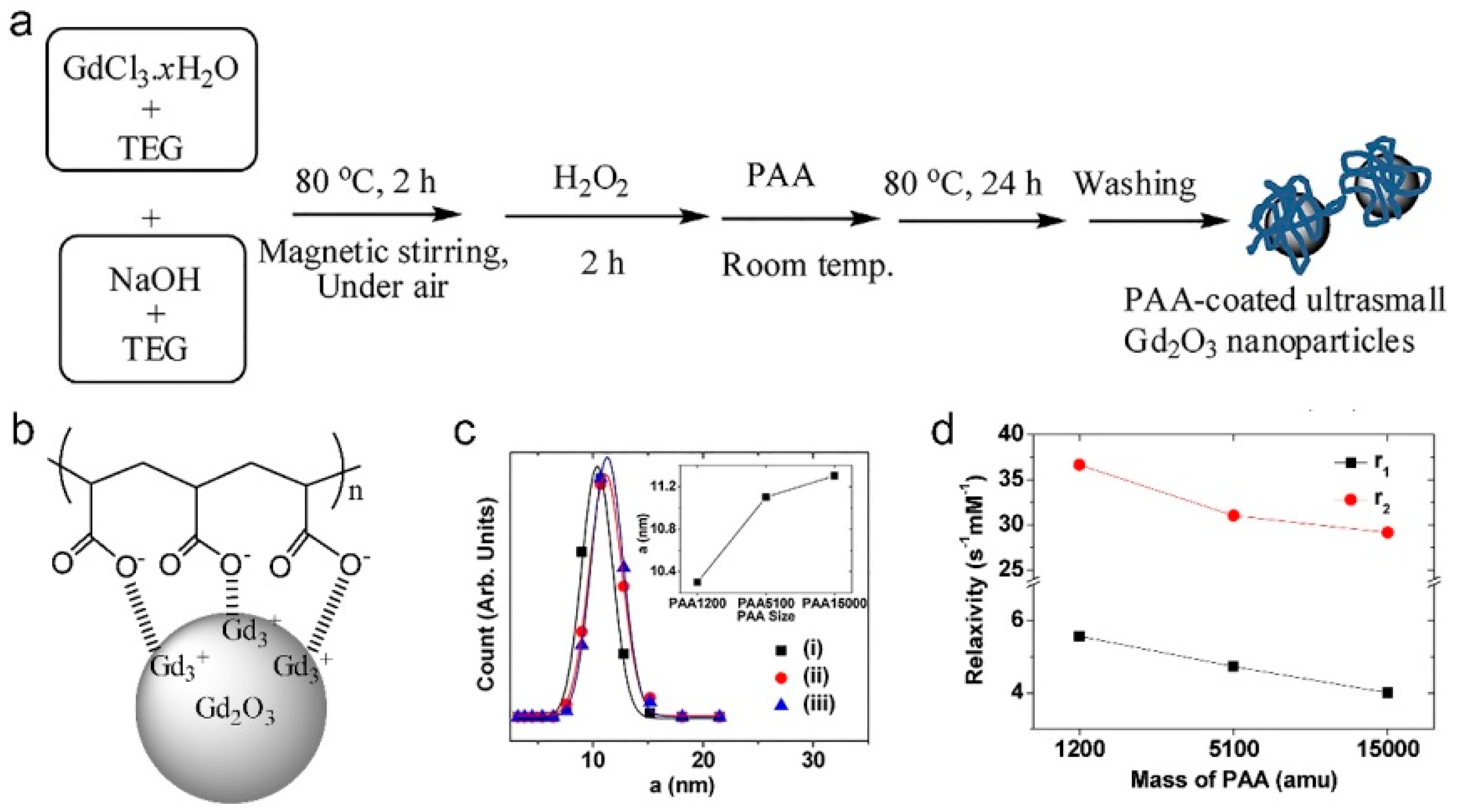

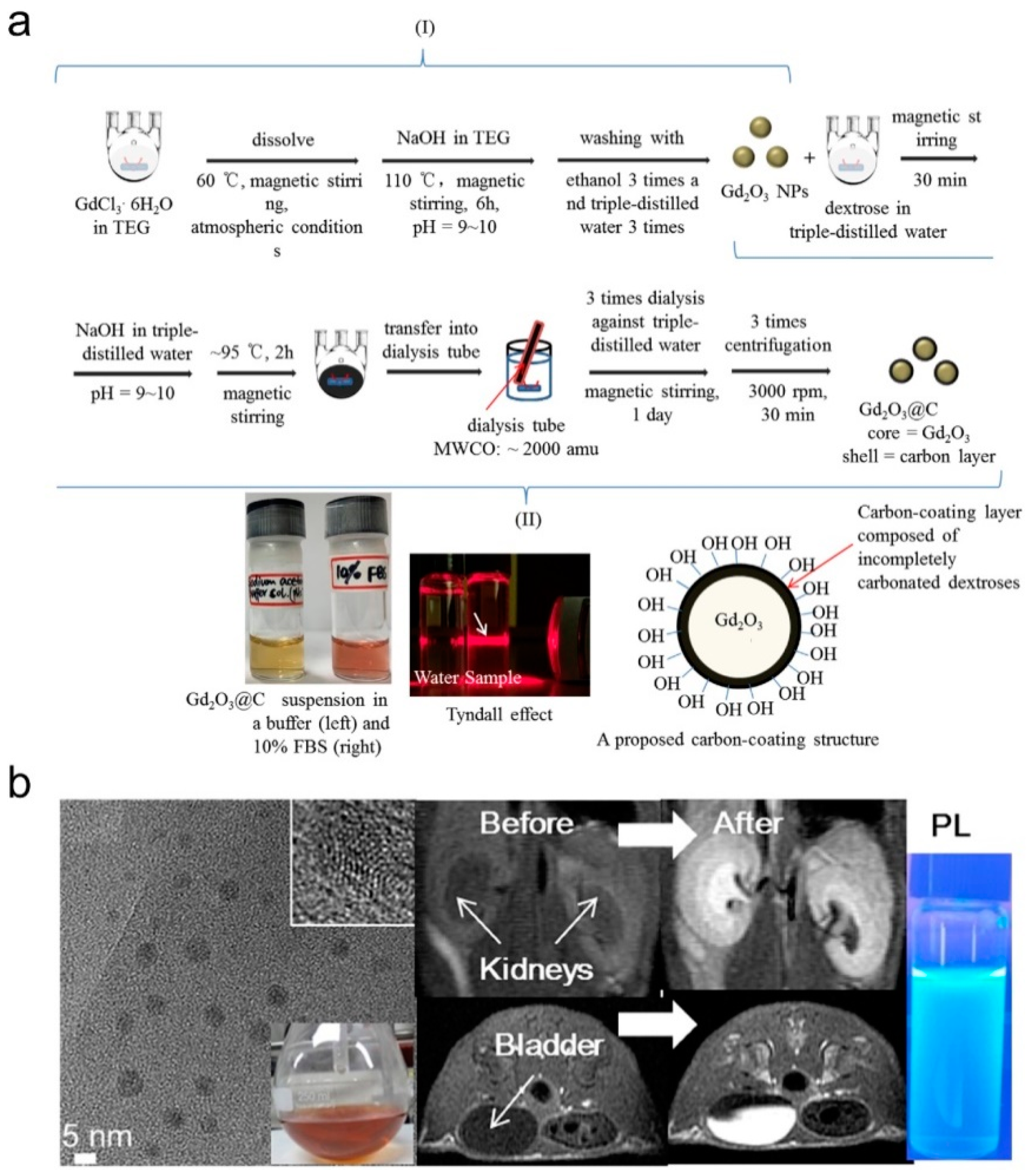

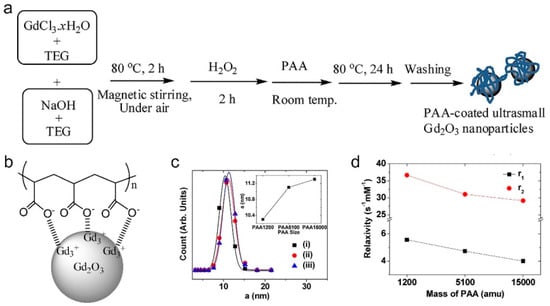

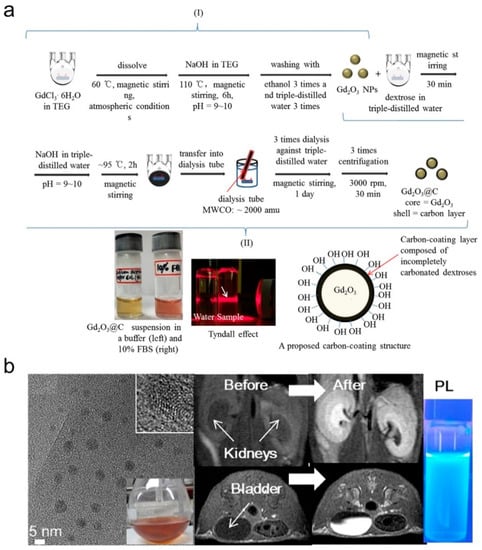

Several methods have been developed to synthesize Gd2O3 NDs for the application in MRCAs [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,74,77,78,79,80]. As early as 2006, Uvdal and coauthors synthesized Gd2O3 NDs (5 to 10 nm in diameter) by thermal decomposition of Gd3+ precursors (Gd(NO3)3·6H2O or GdCl3·6H2O) in the diethylene glycol (DEG) [62]. Both r1 and r2 of the DEG capped Gd2O3 NDs are approximately 2 times higher than those of Gd-DTPA. Lee’s group developed a one-pot synthesis method with two steps for preparing a series of hydrophilic Gd2O3 NDs with high colloidal stability: (1) using GdCl3·6H2O as Gd3+ as precursors, Gd2O3 NDs were firstly synthesized in tripropylene/triethylene glycol (TPG/TEG) under alkaline condition, and aged by H2O2 and/or an O2 flow; (2) the as-prepared Gd2O3 NDs were then stabilized by different coating materials including amino acid, polymers, and carbon [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. As early as 2009, Lee and coauthors synthesized d-glucuronic acid coated Gd2O3 NDs in TPG by using d-glucuronic acid as stabilizer [63]. The d-glucuronic acid coated Gd2O3 NDs with 1.0 nm in diameter have a high r1 (9.9 mM−1⋅s−1), which can easily cross the brain-blood barrier (BBB), causing a strong contrast enhancement in the brain tumor within two hours. Due to the excretion of the injected d-glucuronic acid coated Gd2O3 NDs, the MRI contrast began to decrease at 2 h post-injection. The in vivo MR images of brain tumor, kidney, bladder, and aorta demonstrate that d-glucuronic acid coated Gd2O3 NDs have good tumor-targeting ability, strong blood pool effect, and high renal clearance when the mice were injected intravenously Gd2O3 NDs solution at a dose of 0.07 mmol Gd kg−1. Subsequently, Lee and coauthors successfully synthesized hydrophilic polyacrylic acid (PAA) coated Gd2O3 NDs (average diameter = 2.0 nm) with high biocompatibility by electrostatically binding of -COO− groups of PAA with Gd3+ on the Gd2O3 NDs (as shown in Figure 6) [69]. Because the magnetic dipole interaction between surface Gd3+ and 1H is impeded by the PAA, both r1 and r2 values of Gd2O3 NDs are decreased with increasing the molecular weight of PAA (Mw = 1200, 5100 and 15,000 Da). Very recently, Lee and coauthors synthesized a kind of carbon-coated Gd2O3 NDs (Gd2O3@C, average diameter = 3.1 nm) by using dextrose as a carbon source in the aqueous solution (as shown in Figure 7) [70]. The Gd2O3@C have excellent colloidal stability, very high r1 value (16.26 mM−1⋅s−1, r2/r1 = 1.48), and strong photoluminescence (PL) in the visible region, which can be used as renal clearable MR/PL dual-mode imaging agent.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic representation of the one-pot synthesis of polyacrylic acid (PAA) coated Gd2O3 NDs, (b) the representative PAA surface-coating structure, (c) DLS measurement of (i) PAA 1200, (ii) PAA 5100, and (iii) PAA 15,000 coated Gd2O3 NDs, inset of (c) is the hydrodynamic diameter of PAA coated Gd2O3 NDs as a function of PAA molecular weight, and (d) r1 and r2 values as a function of PAA molecular weight (adapted from Lee et al. 2019 [69], Copyright 2017 the Elsevier B.V. and reproduced with permission).

Figure 7.

(a) Two-step synthesis of Gd2O3@C: (i) the synthesis of Gd2O3 NDs in triethylene glycol (TEG), and (ii) carbon coating on the Gd2O3 ND surfaces in aqueous solution. From left to right at the bottom of (a), photographs of the Gd2O3@C in sodium acetate buffer solution (pH = 7.0) and a 10% FBS in RPMI1640 medium, the Tyndall effect (or laser light scattering) as indicated with an arrow in the Gd2O3@C in water sample (right) with no light scattering in the reference triple-distilled water (left), and a proposed carbon-coating structure of Gd2O3@C. (b) High resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) micrograph of Gd2O3@C, photograph of Gd2O3@C in water, in vivo MRI of mouse before or after intravenously administrated by Gd2O3@C and PL of Gd2O3@C at a dose of 0.1 mmol Gd kg−1 (adapted from Lee et al. 2020 [70], Copyright 2019 the Elsevier B.V. and reproduced with permission).

3.1.2. NaGdF4 Nanodots

Hydrophobic NaGdF4 NDs with narrow size distribution are readily synthesized by pyrolysis methods via a high boiling binary solvent mixture [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. In the presence of oleic acid, the approach has been demonstrated to be able to produce NaGdF4 NDs with high quality (e.g., low crystal defect and good monodispersity) through the thermal decomposition of Gd3+ precursors, NaOH, and NH4F in octadecene. In order to transfer the as-prepared hydrophobic NaGdF4 NDs into aqueous phase, the NaGdF4 NDs surfaces should be capped with appropriate surface-coating materials such as amphiphilic polymers and biomacromolecules. As early as 2011, Veggel and coauthors reported a size-selective synthesis of paramagnetic NaGdF4 NPs with four different sizes (between 2.5 and 8.0 nm in diameter) with good monodispersity by adjusting the concentration of the coordinating ligand (i.e., oleic acid), reaction time, and temperature [82]. The oleate coated NaGdF4 NPs were then transferred into aqueous phase by using polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as phase transfer agent. They found that the r1 values of PVP coated NaGdF4 NPs are decreased from 7.2 to 3.0 mM−1⋅s−1 with increasing the NP size from 2.5 to 8.0 nm. In particular, the r1 value of PVP coated 2.5 nm NaGdF4 NDs is about twice as high as that of MagnevistT under same conditions.

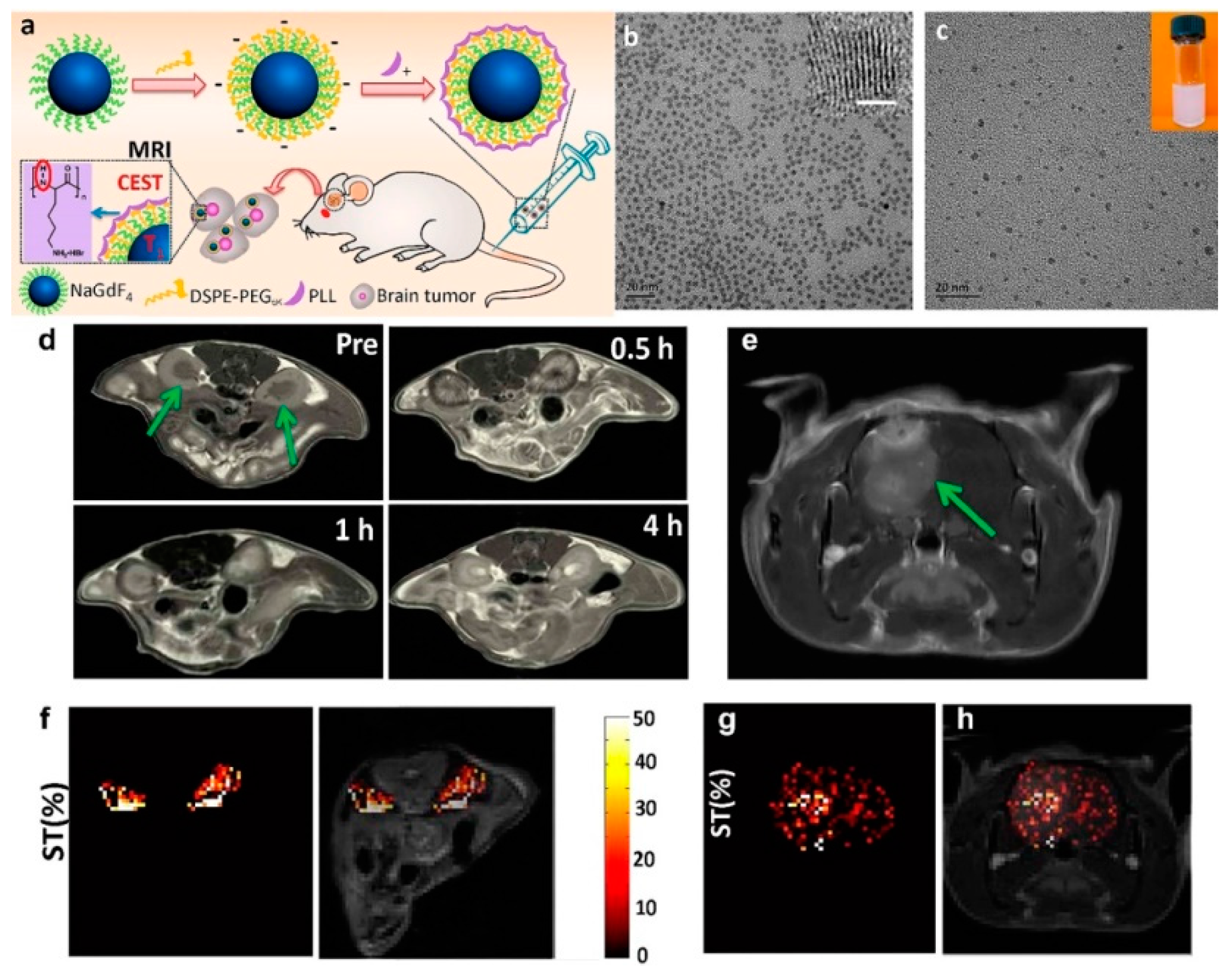

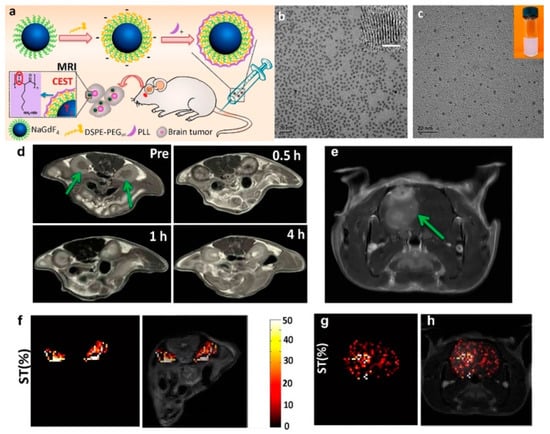

Shi and coauthors successfully employed the amphiphilic molecule, PEG-phospholipids, (such as DSPE-PEG2000 (1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-Poly(ethylene glycol)2000) and/or the mixture of DSPE-PEG2000 and DSPE-PEG2000-NH2 (amine functionalized DSPE-PEG2000)) to convert 2 nm NaGdF4 NDs from hydrophobic to hydrophilic through the van der Waals interactions of the two hydrophobic tails of phospholipid groups of PEG-phospholipids and the oleic acids on the ND surface [84,85]. The PEG-phospholipids/amine functionalized PEG-phospholipids coated NaGdF4 NDs can be further functionalized by other molecules via suitable physical and chemical reactions. For example, poly-l-lysine (PLL) coated NaGdF4 NDs (NaGdF4@PLL NDs) were developed as dual-mode MRCA by layer-by-layer (LbL) self-assembly of positively charged PLL on the negatively charged DSPE-PEG5000 coated NaGdF4 NDs (as shown in Figure 8) [85]. The NaGdF4@PLL ND exhibits high r1 (6.42 mM−1⋅s−1) for T1-weighted MRI, while the PLL shows an excellent sensitive chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) effect for pH mapping (at +3.7 ppm). The results of in vivo small animal experiments demonstrate that NaGdF4@PLL NDs can be used as highly efficient MRCA for precise measurement of in vivo pH value and diagnosis of kidney and brain tumor. Moreover, the NaGdF4@PLL NDs could be excreted through urine with negligible toxicity to body tissues, which holds great promise for future clinical applications.

Figure 8.

(a) Schematic representation of the synthesis of NaGdF4@PLL NDs for T1-weighted and chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MR imaging. (b) TEM and HRTEM (inset, scale bar: 1 nm) micrograph oleic acid-coated NaGdF4 NDs in chloroform. (c) TEM micrograph and photograph (inset) of NaGdF4@PLL NDs in water. (d) In vivo T1-weighted MRI of kidneys of mouse (as arrowed) before and after the intravenous administration of NaGdF4@PLL NDs at a dose of 5 mg Gd kg−1. (e) In vivo T1-weighted MRI of brain tumor (as arrowed) after the intravenous administration of NaGdF4@PLL NDs at a dose of 10 mg Gd kg−1. (f) CEST contrast difference map between pre/post-injection following radio frequency (RF) irradiation at 3.0 μT. Only the kidney signal is displayed in color on the grayscale image to highlight the CEST effect. (g) CEST ST difference map between pre/post-injection at 3.0 μT. Only the brain ventricle signal is displayed in color on the grayscale image to highlight the CEST effect. (h) Merged image of (e) and (g) (adapted from Shi et al. 2016 [85], Copyright 2016 the American Chemical Society and reproduced with permission).

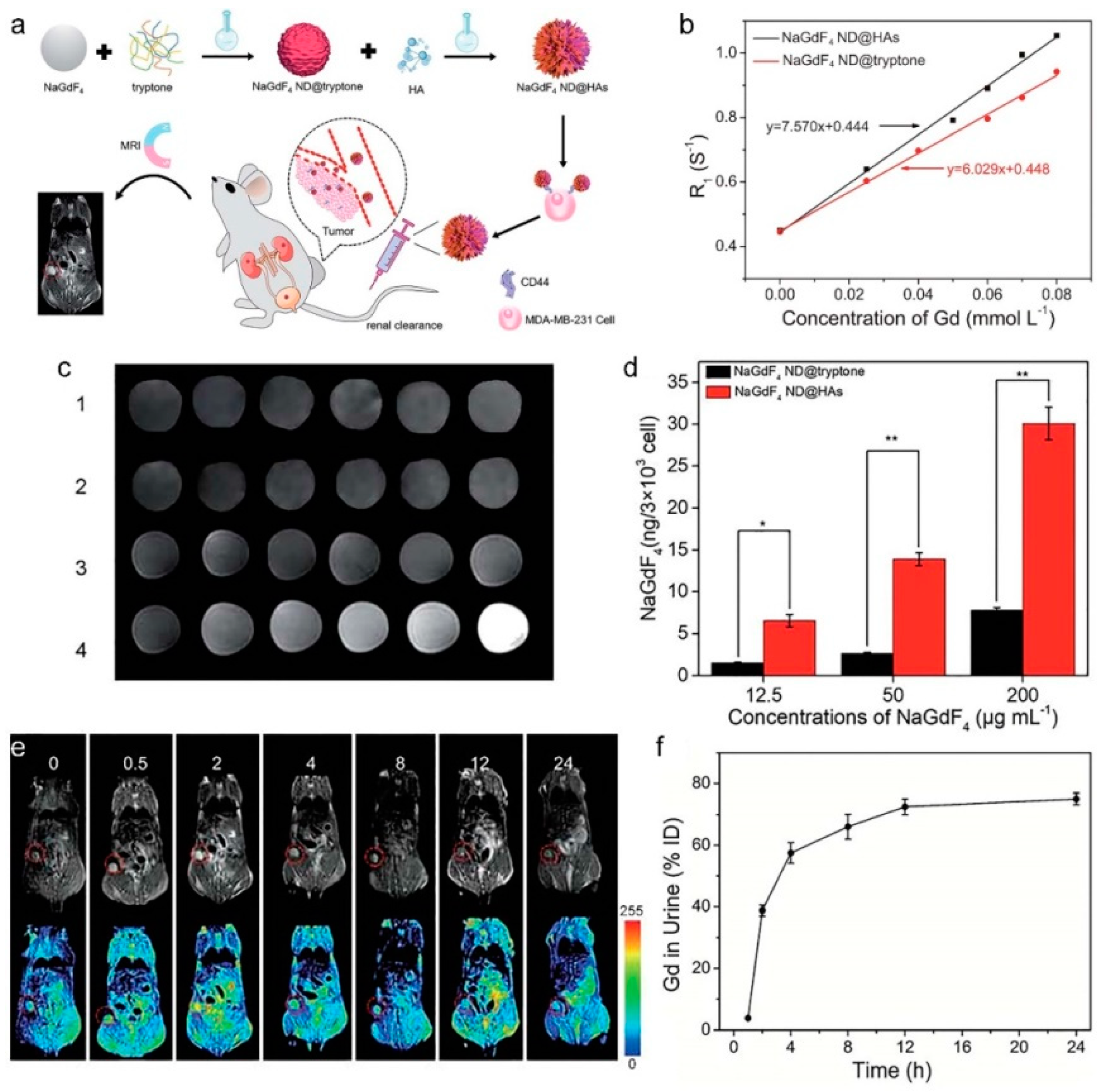

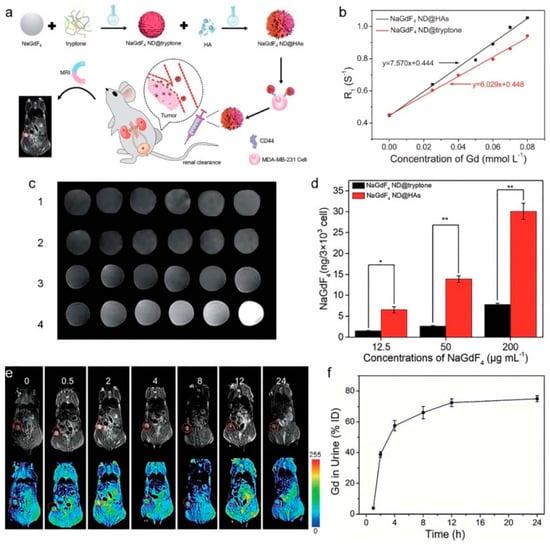

Taking benefit from robust Gd3+-phosphate coordination bonds, our group developed a facile method for transferring hydrophobic NaGdF4 NDs into aqueous phase though ligand exchange reaction between oleate and phosphopeptides in tryptone [86,87]. The tryptone-coated NaGdF4 NDs (tryptone-NaGdF4 NDs) have excellent colloidal stability, low toxicity, outstanding MRI enhancing performance (r1 = 6.745 mM−1⋅s−1), efficient renal clearance, and EPR effect-based passive tumor-targeting ability. Importantly, the tryptone-NaGdF4 NDs can be easily functionalized by other molecules including organic dyes and bioaffinity ligands. As shown in Figure 9, the tryptone-NaGdF4 NDs were further functionalized by hyaluronic acid (HA, a naturally occurring glycosaminoglycan) [87]. The HA functionalized tryptone-NaGdF4 NDs (tryptone-NaGdF4 ND@HAs) exhibit high binding affinity with CD44-positive cancer cells, good paramagnetic property (r1 = 7.57 mM−1⋅s−1) and reasonable biocompatibility. Using MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mouse as a model, the in vivo experimental results demonstrate that the tryptone-NaGdF4 ND@HAs cannot only efficiently accumulate in tumor (ca. 5.3% injection dosage (ID) g−1 at 2 h post-injection), but also have an excellent renal clearance efficiency (ca. 75% ID at 24 h post-injection). The approach provides a useful strategy for the preparation of renal clearable MRCAs with positive tumor-targeting ability. Using a similar phase transferring principle, the peptide functionalized NaGdF4 NDs (pPeptide-NaGdF4 NDs) were prepared by conjugation of the hydrophobic oleate coated NaGdF4 NDs (4.2 nm in diameter) with the mixture of phosphorylated peptides including a tumor targeting phosphopeptide (pD-SP5) and a cell penetrating phosphopeptide (pCLIP6) [88]. Due to its high isoelectric point, the pCLIP6 can enhanced the cellular uptake of pPeptide-NaGdF4 NDs. The pD-SP5 can improve the tumor-targeting ability of pPeptide-NaGdF4 NDs because it has high binding affinity to human tumor cells. The pPeptide-NaGdF4 NDs show low toxicity, outstanding MRI enhancing performance (r1 = 13.2 mM−1⋅s−1) and positive-tumor targeting ability, which were used successfully as efficient MRCA for an in vivo imaging small drug induced orthotopic colorectal tumor (c.a., 195 mm3), when the mice were then intravenously injected with pPeptide-NaGdF4 NDs at a dose of 5 mg Gd kg−1. In addition, the half-life of pPeptide-NaGdF4 NDs in blood is found to be 0.5 h, and more than 70% Gd is excreted with the urine after 24 h intravenous administration.

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic representation of NaGdF4 ND@HAs synthesis, and the application in MRI of tumor through recognizing the overexpressed CD44 on cancer cell membrane. (b) R1 relaxivities of NaGdF4 ND@tryptone and NaGdF4 ND@HAs as a function of the molar concentration of Gd3+ in solution, respectively. (c) MR images of (1) NaGdF4 ND@HA-stained MCF-7 cells, (2) free HA + MDA-MB-231 cells + NaGdF4 ND@HAs, (3) NaGdF4 ND@tryptone-stained MDA-MB-231 cells, (4) NaGdF4 ND@HA-stained MDAMB-231 cells. (d) The amounts of Gd element in the NaGdF4 ND-stained MDA-MB-231cells. Error bars mean standard deviations (n = 5, * p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01 from an analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-test). (e) In vivo MR images and corresponding pseudo color images of Balb/c mouse bearing MDA-MB-231 tumor after intravenous injection of NaGdF4 ND@HAs (10 mg Gd kg−1) at different timed intervals (0 (pre-injection), 0.5, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h post-injection), respectively. (f) The total amounts of NaGdF4 ND@HAs in mouse urine as a function of post-injection times. Error bars mean standard deviations (n = 5) (adapted from Yan et al. 2020 [87], Copyright 2020 The Royal Society of Chemistry and reproduced with permission).

3.2. Iron Nanodots

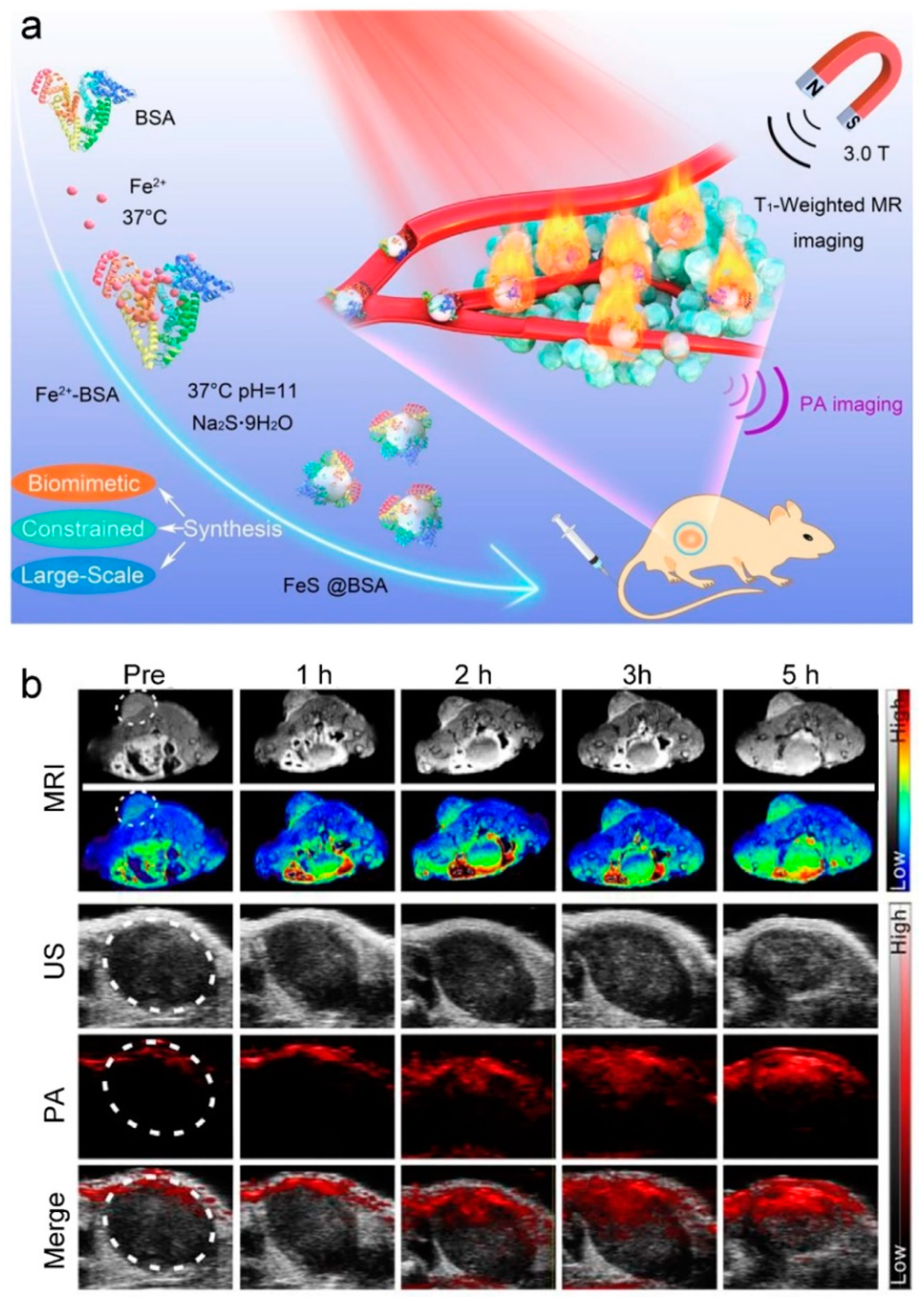

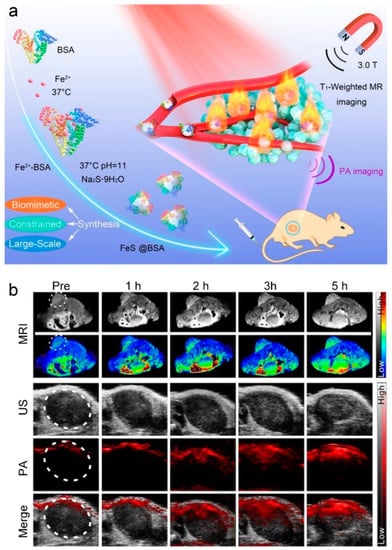

In 1996, the U. S. FDA approved Ferumoxides (SPIONs) as T2-weighted MR CAs for the diagnosis of liver disease [91]. After that, various strategies based on physical, chemical, and biological methods have been developed for synthesizing the SPIONs including FeNDs for using as T2-weighted MRCAs [91,92,93,94,95]. Because of the negative contrast effect and magnetic susceptibility artifacts, it is still a great challenge when the SPION-enhanced T2-weighted MRI is employed to distinguish the lesion region in the tissues with low background MR signals such as bone and vasculature. Recently, several methods have developed for synthesis of FeNDs, which are showing increasing potential as alternatives to Gd3+-based T1-weighted MRCAs because of low magnetization by a strong size-related surface spin-canting effect [96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111]. For instance, Wu and coauthors synthesized a silica-coated Fe3O4 ND (4 nm in diameter), which exhibited a good r1 relaxivity of 1.2 mM−1⋅s−1 with a low r2/r1 ratio of 6.5 [101]. The result of in vivo T1-weighted MR imaging of heart, liver, kidney, and bladder in a mouse demonstrated that silica-coated FeNDs exhibited strong MR enhancement capability, when the mice were then intravenously injected with silica-coated FeNDs at a dose of 2.8 mg Fe kg−1. Shi and coauthors reported a zwitterion l-cysteine (Cys) coated Fe3O4 ND (3.2 nm in diameter, Fe3O4-PEG-Cys) with r1 relaxivity of 1.2 mM−1⋅s−1 [102]. The Fe3O4-PEG-Cys are able to resist macrophage cellular uptake, and display a prolonged blood circulation time with a half-life of 6.2 h. In vivo experimental results demonstrated that the Fe3O4-PEG-Cys were able to be used as a T1-weighted MRCA for enhanced blood pool and tumor MR imaging, when the mice were then intravenously injected with Fe3O4-PEG-Cys at a dose of 0.05 mmol Fe kg−1. Bawendi and coauthors prepared zwitterion-coated ultrasmall superparamagnetic Fe2O3 NDs (ZES-SPIONs) with hydrodynamic size of 5.5 nm for use as Gd3+ free T1-weighted MRCA [103]. The ZES-SPIONs have strong T1-weighted MRI enhancement capacity (r1 = 5.2 mM−1⋅s−1), and the majority of ZES-SPIONs are cleared through the renal route within 24 h intravenous administration at a dose of 0.2 mmol Fe kg−1. As shown in Figure 10, Zhang and coauthors reported a large-scalable (up to 10 L) albumin-constrained strategy to synthesize monodispersed 3 nm ferrous sulfide NDs (FeS@BSA) with an ultralow magnetization by reaction of the mixture of BSA and FeCl2 with Na2S under ambient conditions (pH 11 and 37 °C) [104]. In this case, BSA plays crucial roles in the synthesis process including as a constrained microenvironment reactor for particle growth, a water-soluble ligand for colloidal stability, and a carrier for multifunctionality. FeS@BSAs exhibit high MRI enhancing performance (r1 = 5.35 mM−1⋅s−1), good photothermal conversion efficiency (η = 30.04%), strong tumor-targeting ability, and an efficient renal clearance characteristic. In vivo experiments show that FeS@BSAs have good performance of T1-weighted MR/phototheranostics dual-mode imaging-guided photothermal therapy (PTT) of mouse-bearing 4T1 tumor, demonstrating FeS@BSA to be an efficient T1-weighted MR/PA/PTT theranostic agent.

Figure 10.

(a) Schematic representation of bovine serum albumin (BSA)-constrained biomimetic synthesis of 3 nm FeS@BSA for in vivo T1-weighted MR/phototheranostics dual-mode imaging-guided photothermal therapy (PTT) of tumors. (b) In vivo T1-weighted MR, US, PA, and merged (US and PA) images of tumor after intravenous injection of at a dose of 20 mg FeS@BSA kg−1 (adapted from Zhang et al. 2020 [104], Copyright 2020 Elsevier Ltd. and reproduced with permission).

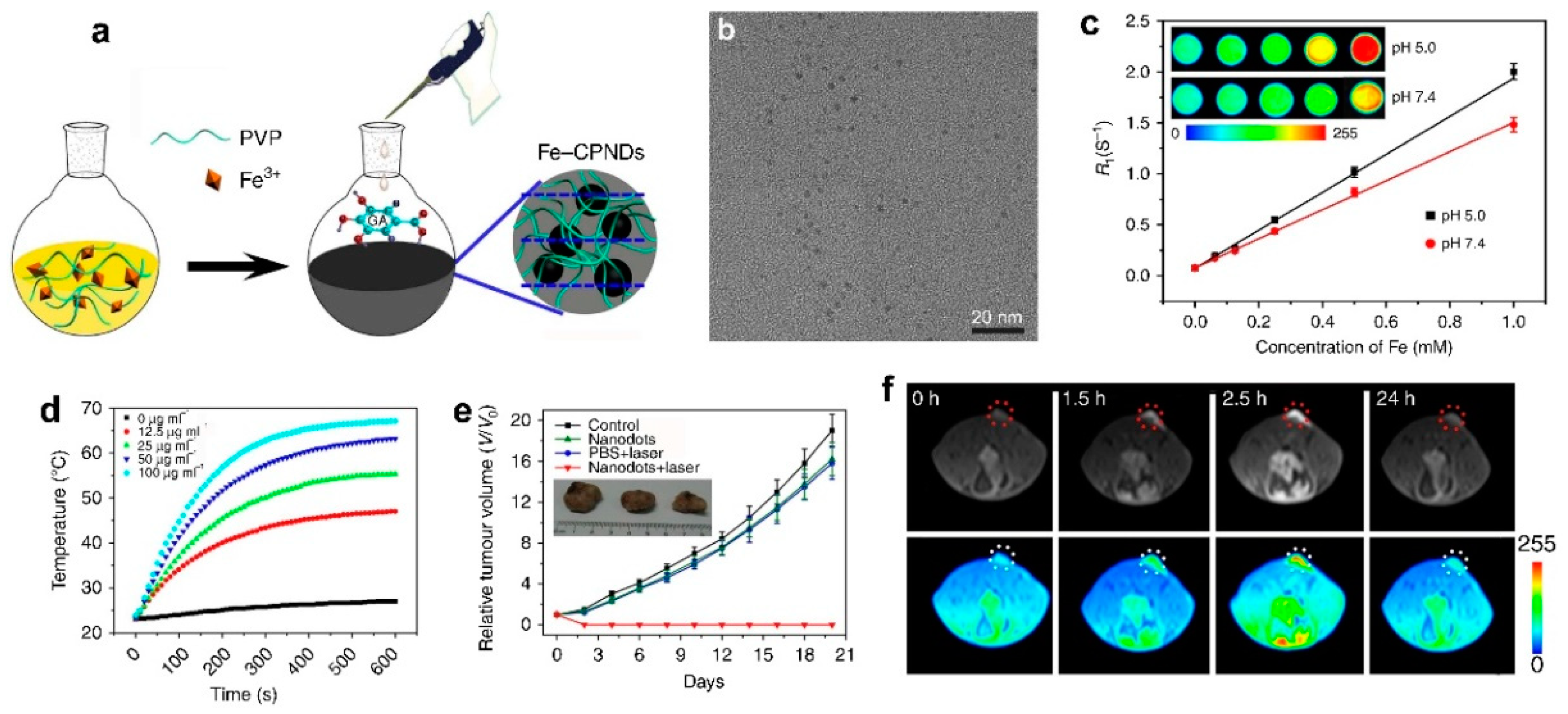

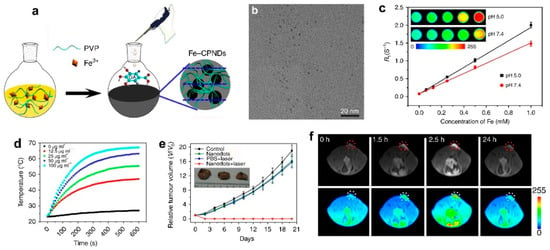

Fe3+ coordination polymer NDs (Fe-CPNDs) were synthesized through the self-assembling the multidental Fe3+-polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) complexes and Fe3+-gallic acid (GA) complexes and used as nanotheranostics for MRI-guided PTT [107,108,109]. For instance, our group has developed a simple and scalable method for synthesizing the pH-activated Fe coordination polymer NDs (Fe-CPNDs) by the coordination reactions among Fe3+, GA, and PVP at ambient conditions (as shown in Figure 11) [107]. The Fe-CPNDs exhibit an ultrasmall hydrodynamic diameter (5.3 nm), nearly neutral Zeta potential (−3.76 mV), pH-activatable MRI imaging contrast (r1 = 1.9 mM−1⋅s−1 at pH 5.0), and outstanding photothermal performance. The Fe-CPNDs were successfully used as T1-weighted MRCA to detect mouse-bearing tumors as small as 5 mm3 in volume, and as a PTT agent to completely suppress tumor growth by MRI-guided PTT, demonstrating that Fe-CPNDs constitute a new class of renal clearable theranostics. In addition, the Fe-CPND-enhanced MRI was successfully employed for noninvasively monitoring the kidney dysfunction by drug (daunomycin)-induced kidney injury, which further highlights the potential in clinical applications of the Fe-CPND [108].

Figure 11.

(a) Schematic representation of the synthesis of Fe-CPNDs. (b) TEM micrograph of Fe-CPNDs. (c) The effect of solution pH on the R1 relaxivity of Fe-CPNDs. (d) Temperature elevation of Fe-CPNDs solutions with various concentrations under 1.3 W cm−2 808 nm NIR laser irradiation for 10 min. (e) Tumor growth curves of different groups of mice after intravenous treatments. The inset shows the digital photographs of tumors collected from different groups of mice at day 20th post-administration. (f) In vivo MR images of the SW620 tumor-bearing nude mouse after intravenous injection of at a dose of 0.25 mg Fe kg−1 (The tumor was marked by circle, which was about 5 mm3 in volume.) after the intravenous injection of Fe-CPNDs at different time intervals (0 h indicates pre-injection) (adapted from Liu et al. 2015 [107], Copyright 2015 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. and reproduced with permission).

Development of contrast agents for simultaneously T1-/T2-weighted dual-mode MRI may circumvent the drawbacks of single imaging modalities. Iron-based NDs are also able to serve as T1-/T2-weighted dual-mode MRCAs [110,111,112,113]. Uvdal and coauthors synthesized a series of water-dispersible PAA-coated Fe3O4 NDs via a modified one-step coprecipitation approach [110]. In particular, the 2.2 nm PAA coated Fe3O4 NDs have relatively high relaxivities (r1 = 6.15 mM−1⋅s−1 and r2 = 28.62 mM−1⋅s−1) and low r2/r1 ratio (4.65). Using a mouse model, the in vivo experiments indicate that the 2.2 nm PAA-coated Fe3O4 NDs exhibit long-term circulation, low toxicity, and great contrast enhancement (brightened on the T1-weighted and darkened on the T2-weighted MR images), when the mice were then intravenously injected with PAA-coated Fe3O4 NDs with a dose of 0.0125 mmol Fe kg−1. The in vivo results demonstrate that the 2.2 nm PAA-coated Fe3O4 NDs have great potential as T1-/T2-weighted dual-mode MRCA for clinical applications including diagnosis of renal failure, myocardial infarction, atherosclerotic plaque, and tumor. Very recently, Shi and coauthors developed a strategy for preparing switchable T1/T2-weighted dual-mode MRCA by formation of cystamine dihydrochloride (Cys) cross-linked Fe3O4 NDs clusters [113]. The Fe3O4 NDs clusters, with a hydrodynamic size of 134.4 nm, and can be dissociated to single 3.3 nm Fe3O4 NDs under a reducing microenvironment (e.g., 10 mmol L−1 glutathione (GSH)) because of redox-responsiveness of the disulfide bond of Cys. The Fe3O4 NDs clusters exhibit a dominant T2-weighted MR effect with an r2 of 26.4 mM−1⋅s−1, while Fe3O4 NDs have a strong T1-weighted MR effect with an r1 of 3.9 mM−1⋅s−1. Due to the reductive tumor microenvironment, the Fe3O4 NCs can be utilized for dynamic precision imaging of a subcutaneous tumor model in vivo, and pass through the kidney filter, when the mice were then intravenously injected Fe3O4 NCs with a dose of 2.5 mmol Fe kg−1.

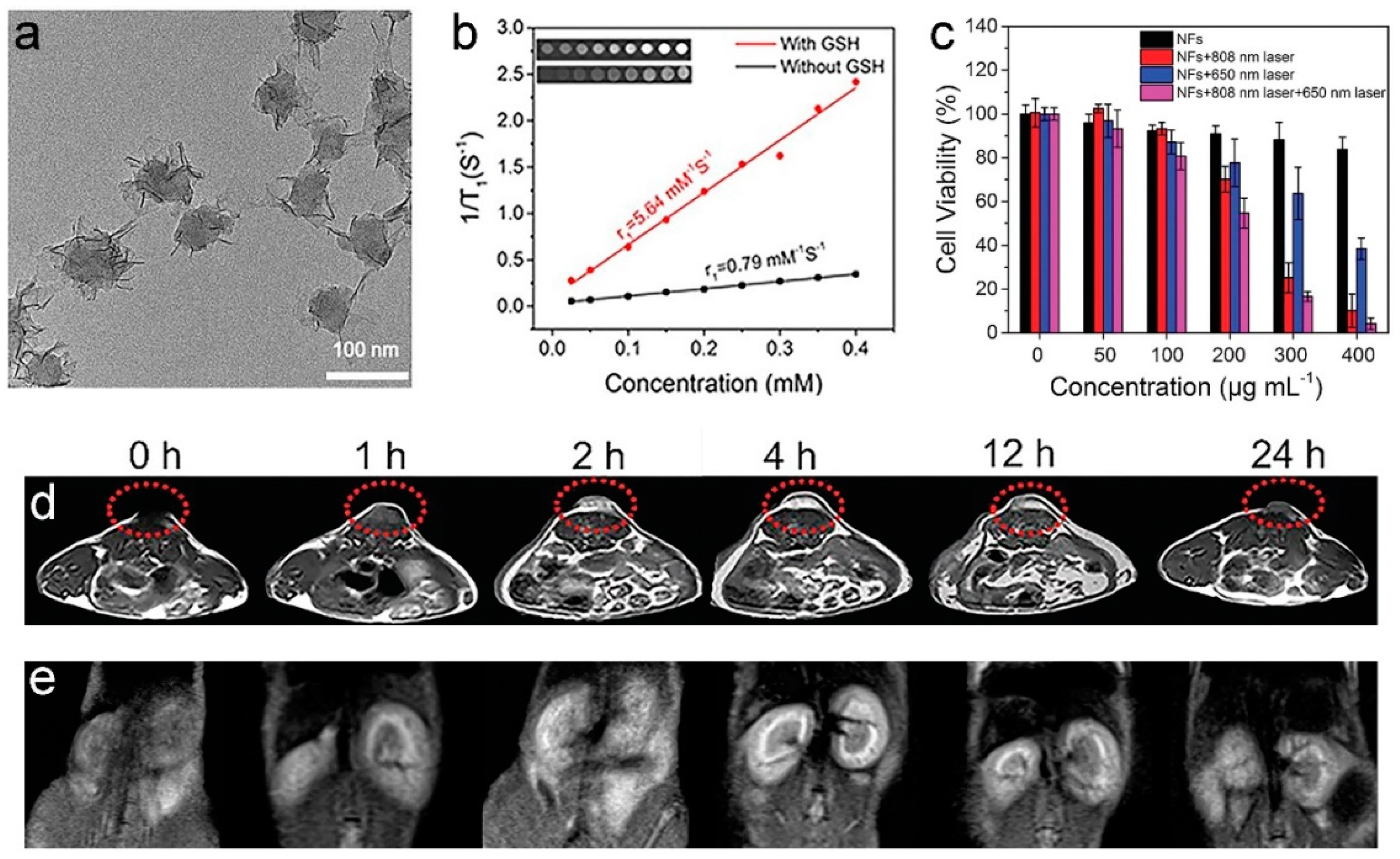

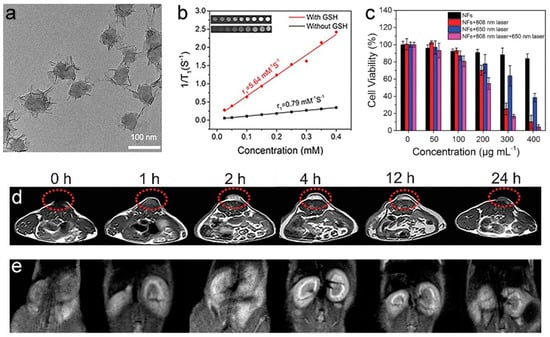

3.3. Other Paramagnetic Metal-Based Nanomaterials

Due to their in vivo safety, Mn2+-based T1-weighted MRCAs have attracted increasing attention [114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134]. Although free Mn2+ has a higher r1 than those of Mn-based nanomaterials, Mn2+ exhibits low accumulation and poor performance for disease contrast because of its short blood retention time in vivo [114,115,116,117,118,119]. The increase of Mn2+ accumulation in a tumor can be achieved through the design of pH/GSH-activated Mn-based nanomaterials because a tumor has weakly acidic microenvironment and high concentration of GSH, and nanomaterials can efficiently accumulate in a tumor by EPR effect [123,124,125,126,127,128,129]. Therefore, several tumor microenvironment activatable Mn-based nanotheranostic systems have been constructed for T1-weighted MRI-guided therapy. We have synthesized the polydopamine@ultrathin manganese dioxide/methylene blue nanoflowers (PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs) for the T1-weighted MRI-guided PTT/photodynamic therapy (PDT) synergistic therapy of tumor (as shown in Figure 12) [125]. In the presence of 5 mmol⋅L−1 GSH, the r1 of PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs is significantly increased from 0.79 to 5.64 mM−1⋅s−1 since the ultrathin MnO2 nanosheets on PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs can be reduced into Mn2+ ions by GSH. Due to the performance in response to the tumor microenvironment, the PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs show an enhancement 3 times that of the T1-weighted MRI signal at the tumor site at 4 h post-injection. The Mn2+ can be diffused from the tumor to the circulatory system and excreted from the body through renal clearance. In addition, doping of Mn2+ into the matrix of other metallic NDs and/or formation of Mn2+-complexes/nanocomposites can also improve its T1-weighted MR contrast ability [115,130,131,132,133,134]. For example, Wang and coauthors developed a Mn2+-based MRCA (MNP-PEG-Mn) through chelation of Mn2+ with 5.6 nm water-soluble melanin NDs [134]. The r1 (20.56 mM−1⋅s−1) of as-prepared MNP-PEG-Mn is much higher than that of Gadodiamide (6.00 mM−1⋅s−1). Using a 3T3 tumor-bearing mouse as model, in vivo MRI experiments demonstrated that MNP-PEG-Mn (200 μL of 8 mg mL−1 MNP-PEG-Mn PBS solution) showed excellent tumor-targeting specificity, and could be efficiently excreted via renal and hepatobiliary pathways with negligible toxicity.

Figure 12.

(a) TEM micrographs of PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs. (b) The r1 values of PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs with and without 5 mmol L−1 GSH. (c) An assessment of PDT/PTT efficacy using PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs via CCK-8 assays. In vivo MR images of HCT 116 tumor-bearing mouse (d) tumor and (e) kidneys different time points after the intravenous injection of PDA@ut-MnO2/MB NFs (0, 1, 2, 4, 12, and 24 h; 0 h means pre-injection) at a dose of 10 mg Mn kg−1 (adapted from Sun et al. 2019 [125], Copyright 2019 The Royal Society of Chemistry and reproduced with permission).

Because Dy3+ and Ho3+ ions exhibit relatively high magnetic moments among of lanthanide (III) (Ln3+) ions, Dy and Ho NDs are believed as promising candidates for T2-weighted MRCAs with renal excretion [135,136,137,138,139]. As early as 2011, Lee and coauthors developed a facile one-pot method for synthesis of d-glucuronic acid-coated Ln2O3 NDs (Ln = Eu, Gd, Dy, Ho, and Er) [138]. They demonstrated that the d-glucuronic acid-coated 3.2 nm Dy2O3 NDs have high r2 (65.04 mM−1⋅s−1) and very low r1 (0.008 mM−1⋅s−1). After injection of the Dy2O3 NDs at a dose of 0.05 mmol Dy kg−1 through tail vein of mouse, the clearly negative MR contrast enhancement in both liver and kidneys of mouse are observed in in vivo T2-weighted MRI. The Dy2O3 NDs are also excreted from the body through the renal route, which is prerequisite for clinical applications as a MRCA.

4. Dual Paramagnetic Metal Nanodots

The MR contrast capabilities of nanomaterials can be further improved while two paramagnetic metallic ions are integrated into one nanoplatform [140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155]. For instance, Zhou and coauthors constructed a 4.95 nm triple-mode imaging platform by doping of Mn2+ and 68gallium (III) (68Ga3+) into the matrix of copper sulfide (CuS) NDs using BSA as the synthetic template [143]. Although the Mn2+/68Ga3+-CuS@BSA NDs have relatively low r1 (0.1119 mM−1⋅s−1, the ratio of r2/r1 = 1.67), in vivo experimental results of SKOV-3 ovarian tumor-bearing mouse demonstrated that the as-prepared Mn2+/68Ga3+-CuS@BSA NDs (150 μL solution at 2 OD concentration of NDs) could be used as an excellent agent for T1-weihted MR/positron emission tomography (PET)/photoacoustic (PAT) triple-mode imaging-guided PTT of the tumor, and were efficiently cleared via the renal-urinary route. Very recently, our group constructed a multifunctional nanotheranostic (MnIOMCP) for active tumor-targeting T1-/T2-weighted dual-mode MRI-guided biological-photothermal therapy (bio-PTT) through bioconjugation of the monocyclic peptides (MCP, the CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) antagonist) with 3.8 nm manganese-doped iron oxide NDs (MnIO NDs) [146]. The MnIOMCP displays reasonable T1-/T2-weighted MR contrast abilities (r1 = 13.1 mM−1⋅s−1, r2 = 46.6 mM−1⋅s−1 and r2/r1 = 3.56), good photothermal conversion efficiency (η = 28.8%), strong tumor-targeting ability (∼15.9% ID g−1 at 1 h after intravenous injection with a dose of 10 mg [Mn + Fe] kg−1) and clear inhibition of CXCR4-positive tumor growth. In addition, the MnIOMCP at can be rapidly excreted from the body through renal clearance (about 75% ID of MnIOMCP found in urine at 24 h post-injection), which illuminates a new pathway for the development of efficient nanotheranostics with high biosafety. In addition, the r1 and/or r2 values of Ln3+-based nanomaterials could be increased by mixing paramagnetic transition metal ions into them owing to unpaired 3d-electrons of transition metal ions [151,152,153,154,155]. Gao and coauthors reported a facile strategy to design and synthesis of zwitterionic dopamine sulfonate-coated 4.8 nm gadolinium-embedded iron oxide NDs (GdIO@ZDS), which showed a hydrodynamic diameter of about 5.2 nm in both PBS buffer and BSA solution [155]. The combination of the spincanting effects and the collection of Gd3+ within small-sized GdIO NDs led to a strongly enhanced T1-weighted MR contrast effect, which exhibited a high r1 of 7.85 mM−1⋅s−1 and a low r2/r1 ratio of 5.24. Using SKOV3-bearing mouse as a model, the in vivo experimental results demonstrated that the GdIO@ZDS with a dose of 2.0 mg GdIO@ZDS kg−1 are suitable candidates as excellent T1-weighted MRCAs for tumor imaging and disease diagnosis because they have relatively long circulation half-life (∼50 min), passive-tumor targeting capacity, and efficient renal clearance ability.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

In summary, we have illustrated the recent advances in the development of renal clearable MRCAs including Gd3+-based composites and MNDs. Compared to conventional small molecule Gd3+-complex contrast agents, the composites/MNDs have demonstrated improved MR signal intensity, targeting ability, and longer circulation time both in vitro and in small animal disease models, especially for cancer diagnosis. In particular, with the help of nanotechnology, the recent research developments have progressed towards construction of renal clearable MRCAs with multifunctionality, which enables us to integrate several functions at the same time, such as simultaneous disease targeting, multimodal imaging, and therapy. For instance, several unique characteristics of MNDs enable their use for selective cancer theragnostics, which include: (a) their size, which leads to preferential accumulation of MNDs in tumors though EPR effect, wide MRI time window by prolonging circulation time, and completely excreted from the body within a reasonable period of time (i.e., within a few of days) through renal clearance; (b) high surface-to-volume ratios, which result in strong enhancement of MR signal at ROI through increasing the interaction opportunities of 1H with paramagnetic ions; and (c) large surface area, which exhibits the possibility to load different molecular therapeutics for MRI-guided therapy and/or functionalize with cancer-homing ligands for achieving positive-tumor targeting. The performance of MND-based MRCAs could be further improved through optimizing one or more of the above-mentioned characteristics of the MNDs. The renal clearable composite-/MND-based MRCAs have, indeed, bright prospects regarding their possibilities for biomedical applications, which have already been demonstrated in the scientific literature.

Unfortunately, very few MND-based MRCAs were approved for clinical application except SPIONs (Ferumoxides). On the other hand, the need for specific molecular information is greater than ever, since we are entering into the era of precision medicine. The noninvasive diagnostic or screening methods such as MRI can efficiently help patients to avoid ineffective and/or costly treatments because many of the newly developed powerful and expensive therapies are only effective in a subset of patients. This situation strongly requires the development of high-performance contrast agents to improve the accuracy of molecular imaging. The clinical translation of MND-based MRCAs research is generally impeded by the significant heterogeneity in the construction of these agents. Up to date, the MND-based MRCAs are still in the experimental stage. There are several technical challenges regarding the MND-based MRCAs for clinical trials that need to be clearly addressed before they are evaluated in humans. For example, the safety and efficacy of the MND-based MRCAs should be comprehensively evaluated. Ongoing research should focus on evaluating the biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and ultimate fates in vivo, improving targeting specificity while minimizing toxicity, and demonstrating the translational potential with appropriate animal models. It is critical to develop cost-effective methods for the kilogram-scale production of MND-based MRCAs since the MRCAs are normally administered in gram quantities. This matter could be solved by systematic optimization of synthesis conditions of polyol methods and thermal decomposition methods. The leakage of Gd3+ should be minimized while Gd3+NDs were used as MRCAs. Future efforts should aim to synthesize chelating agents with a high Gd3+ binding constant, and/or develop coating materials with highly stable physicochemical properties and excellent biocompatibility. In addition, integration of two or more paramagnetic metallic elements into a single hybrid ND is beneficial to circumvent their individual drawbacks and potentially provide more comprehensive imaging information through T1-/T2-weighted dual-mode MRI. The MNDs are providing revolutionary potential as new MRCAs, which could achieve various clinical applications through close cooperation among of multidisciplinary teams of chemists, materials scientists, biologists, pharmacists, physicians, and imaging experts, and have a strongly positive impact on human health.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, X.L., Y.S., G.L. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, X.L., L.M., G.L. and Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JILIN PROVINCIAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT and NATIONAL NATURAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION OF CHINA, grant numbers 20190701052GH and 21775145.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Department, and National Natural Science Foundation of China for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weissleder, R.; Mahmood, U. Molecular imaging. Radiology 2001, 219, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.M.; Jenkinson, M.; Woolrich, M.W.; Beckmann, C.F.; Behrens, T.E.J.; Johansen-Berg, H.; Bannister, P.R.; De Luca, M.; Drobnjak, I.; Flitney, D.E.; et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 2004, 23, S208–S219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravan, P.; Ellison, J.J.; McMurry, T.J.; Lauffer, R.B. Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: Structure, dynamics, and applications. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 2293–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, E.J.; Datta, A.; Jocher, C.J.; Raymond, K.N. High-relaxivity MRI contrast agents: Where coordination chemistry meets medical imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8568–8580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, N.A.; Peng, S.; Cheng, K.; Sun, S. Magnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, functionalization, and applications in bioimaging and magnetic energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2532–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, A.Y. Multimodality imaging probes: Design and challenges. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3146–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, G.-L.; Wong, W.-T. An introduction to molecular imaging. In The Chemistry of Molecular Imaging; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lohrke, J.; Frenzel, T.; Endrikat, J.; Alves, F.C.; Grist, T.M.; Law, M.; Lee, J.M.; Leiner, T.; Li, K.-C.; Nikolaou, K.; et al. 25 Years of contrast-enhanced MRI: Developments, current challenges and future perspectives. Adv. Ther. 2016, 33, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahsner, J.; Gale, E.M.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, A.; Caravan, P. Chemistry of MRI contrast agents: Current challenges and new frontiers. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 957–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasch, R.C. Methods of contrast enhancement for NMR imaging and potential applications-A subject review. Radiology 1983, 147, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3995–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Kattel, K.; Park, J.Y.; Chang, Y.; Kim, T.J.; Lee, G.H. Paramagnetic nanoparticle T-1 and T-2 MRI contrast agents. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 12687–12700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, N.Z.; Gadjanski, I.; Durand, J.-O. Magnetic nanoarchitectures for cancer sensing, imaging and therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Sherwood, J.A.; Sun, Z. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as T-1 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, L.; Gao, J.; Chen, X. Structure-relaxivity relationships of magnetic nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1804567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Xu, K.; Taratula, O.; Farsad, K. Applications of nanoparticles in biomedical imaging. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 799–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lee, J.S.H.; Zhang, M. Magnetic nanoparticles in MR imaging and drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longmire, M.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: Considerations and caveats. Nanomedicine 2008, 3, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, R.; Yang, C.; Gao, M. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: From preparations to in vivo MRI applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 6274–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.K.; Reddy, M.K.; Morales, M.A.; Leslie-Pelecky, D.L.; Labhasetwar, V. Biodistribution, clearance, and biocompatibility of iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles in rats. Mol. Pharmaceut. 2008, 5, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-N.; Poon, W.; Tavares, A.J.; McGilvray, I.D.; Chan, W.C.W. Nanoparticle-liver interactions: Cellular uptake and hepatobiliary elimination. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, J.T.; Hudson-Smith, N.V.; Landy, K.M.; Haynes, C.L. Understanding nanoparticle toxicity mechanisms to inform redesign strategies to reduce environmental impact. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Frangioni, J.V. Nanoparticles for biomedical imaging: Fundamentals of clinical translation. Mol. Imaging 2010, 9, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, V.M. Critical questions regarding gadolinium deposition in the brain and body after injections of the gadolinium-based contrast agents, safety, and clinical recommendations in consideration of the EMA’s pharmacovigilance and risk assessment committee recommendation for suspension of the marketing authorizations for 4 linear agents. Investig. Radiol. 2017, 52, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Na, H.B.; Song, I.C.; Hyeon, T. Inorganic nanoparticles for MRI contrast agents. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2133–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.R.; Parker, D.L.; Goodrich, K.C.; Wang, X.H.; Dalle, J.G.; Buswell, H.R. Extracellular biodegradable macromolecular gadolinium(III) complexes for MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2004, 51, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaraza, A.J.L.; Bumb, A.; Brechbiel, M.W. Macromolecules, dendrimers, and nanomaterials in magnetic resonance imaging: The interplay between size, function, and pharmacokinetics. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2921–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelkar, S.S.; Reineke, T.M. Theranostics: Combining imaging and therapy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011, 22, 1879–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detappe, A.; Kunjachan, S.; Sancey, L.; Motto-Ros, V.; Biancur, D.; Drane, P.; Guieze, R.; Makrigiorgos, G.M.; Tillement, O.; Langer, R.; et al. Advanced multimodal nanoparticles delay tumor progression with clinical radiation therapy. J. Control. Release 2016, 238, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellico, J.; Ellis, C.M.; Davis, J.J. Nanoparticle-based paramagnetic contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2019, 1845637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Artemov, D. Biocompatible blood pool MRI contrast agents based on hyaluronan. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2011, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogna, M.; Cloots, R.; Luxen, A.; Jerome, C.; Desreux, J.-F.; Detrembleur, C. Design and synthesis of novel DOTA(Gd3+)-polymer conjugates as potential MRI contrast agents. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 12917–12926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopf, E.; Sankaranarayanan, J.; Chan, M.; Mattrey, R.; Almutairi, A. An extracellular MRI polymeric contrast agent that degrades at physiological pH. Mol. Pharmaceut. 2012, 9, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, R.; Melancon, M.P.; Wong, K.; You, J.; Huang, Q.; Bankson, J.; Liang, D.; Li, C. The degradation and clearance of Poly(N-hydroxypropyl-l-glutamine)-DTPA-Gd as a blood pool MRI contrast agent. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5376–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Xue, R.; You, T.; Li, X.; Pei, F. A new biodegradable and biocompatible gadolinium (III)-polymer for liver magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2015, 33, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; He, Y.; Qu, J.; Effenberg, C.; Xia, J.; Appelhans, D.; Shi, X. Gd-Chelated poly(propylene imine) dendrimers with densely organized maltose shells for enhanced MR imaging applications. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaron, A.; Vibhute, S.; Bianchi, A.; Guenduez, S.; Kotb, S.; Sancey, L.; Motto-Ros, V.; Rizzitelli, S.; Cremillieux, Y.; Lux, F.; et al. Ultrasmall nanoplatforms as calcium-responsive contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Small 2015, 11, 4900–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S.M.; Robison, L.; Parigi, G.; Olszewski, A.; Drout, R.J.; Gong, X.; Islamoglu, T.; Luchinat, C.; Farha, O.K.; Meade, T.J. Maximizing magnetic resonance contrast in Gd(III) nanoconjugates: Investigation of proton relaxation in zirconium metal-organic frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2020, 12, 41157–41166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhong, J.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J.; Cheng, J.; Song, R.; Yi, C. Facile synthesis of gadolinium (III) chelates functionalized carbon quantum dots for fluorescence and magnetic resonance dual-modal bioimaging. Carbon 2015, 93, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Shen, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Z. Ultrasmall graphene oxide based T-1 MRI contrast agent for in vitro and in vivo labeling of human mesenchymal stem cells. Nanomedicine 2018, 14, 2475–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Chelator-free conjugation of Tc-99m and Gd3+ to pegylated nanographene oxide for dual-modality SPECT/MR imaging of lymph nodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2017, 9, 42612–42621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, G.D.; Tang, W.; Todd, T.; Zhen, Z.; Tsang, C.; Hekmatyar, K.; Cowger, T.; Hubbard, R.B.; Zhang, W.; et al. Gd-encapsulated carbonaceous dots with efficient renal clearance for magnetic resonance imaging. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6761–6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Ye, D.; Zhang, X.; Dong, F.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Shen, X.; Kong, J. One-pot synthesis of Gd3+-functionalized gold nanoclusters for dual model (fluorescence/magnetic resonance) imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 3545–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Pan, F.; Tian, Y.; Tang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Hu, A. Facile synthesis of Gd(III) metallosurfactant-functionalized carbon nanodots with high relaxivity as bimodal imaging probes. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 29441–29447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.-H.; Sheng, Z.-H.; Zhang, P.-F.; Yang, D.-Z.; Liu, S.-H.; Gong, P.; Gao, D.-Y.; Fang, S.-T.; Ma, Y.-F.; Cai, L.-T. Hybrid gold-gadolinium nanoclusters for tumor-targeted NIRF/CT/MRI triple-modal imaging in vivo. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 1624–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hao, G.; Yao, C.; Hu, S.; Hu, C.; Zhang, B. Paramagnetic albumin decorated CuInS2/ZnS QDs for CD133(+) glioma bimodal MR/fluorescence targeted imaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 4110–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Xiao, L. Gd3+-Functionalized gold nanoclusters for fluorescence-magnetic resonance bimodal imaging. Biomater. Sci. 2017, 5, 2122–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Kang, Y.-F.; Yin, X.-B. Red fluorescence-magnetic resonance dual modality imaging applications of gadolinium containing carbon quantum dots with excitation independent emission. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 3422–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truillet, C.; Bouziotis, P.; Tsoukalas, C.; Brugiere, J.; Martini, M.; Sancey, L.; Brichart, T.; Denat, F.; Boschetti, F.; Darbost, U.; et al. Ultrasmall particles for Gd-MRI and Ga-68-PET dual imaging. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2015, 10, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Johnson, A.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Erokwu, B.O.; Springer, S.; Lou, J.; Ramamurthy, G.; Flask, C.A.; Burda, C.; et al. Targeted radiosensitizers for MR-guided radiation therapy of prostate cancer. Nano Lett. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivero-Escoto, J.L.; Taylor-Pashow, K.M.L.; Huxford, R.C.; Della Rocca, J.; Okoruwa, C.; An, H.; Lin, W.; Lin, W. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanospheres with cleavable Gd(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: Synthesis, characterization, target-specificity, and renal clearance. Small 2011, 7, 3519–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Mou, Q.; Sun, M.; Yu, C.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Zhu, X.; Yan, D.; Shen, J. Cancer theranostic nanoparticles self-assembled from amphiphilic small molecules with equilibrium shift-induced renal clearance. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1703–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.N.; Baker, G.A. Luminescent carbon nanodots: Emergent nanolights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6726–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Shen, W.; Gao, Z. Carbon quantum dots and their applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, B.; Bisht, T. Carbon nanodots as peroxidase nanozymes for biosensing. Molecules 2016, 21, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J.; Peng, Z.; Leblanc, R.M. Cancer targeting and drug delivery using carbon-based quantum dots and nanotubes. Molecules 2018, 23, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekoueian, K.; Amiri, M.o.; Sillanpaa, M.; Marken, F.; Boukherroub, R.; Szunerits, S. Carbon-based quantum particles: An electroanalytical and biomedical perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4281–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Gong, A.; Tan, Y.; Miao, J.; Gong, Y.; Sun, M.; Ju, H.; et al. Engineered gadolinium-doped carbon dots for magnetic resonance imaging-guided radiotherapy of tumors. Biomaterials 2017, 121, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Xuan, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, X.; Lian, G.; Li, H. Gadolinium-doped carbon dots with high quantum yield as an effective fluorescence and magnetic resonance bimodal imaging probe. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 688, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hao, X.; Lu, W.; Wang, R.; Shan, X.; Chen, Q.; Sun, G.; Liu, J. Facile preparation of double rare earth-doped carbon dots for MRI/CT/FI multimodal imaging. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, N.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Deng, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, L.; Gu, W. Microwave-assisted polyol synthesis of gadolinium-doped green luminescent carbon dots as a bimodal nanoprobe. Langmuir 2014, 30, 10933–10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, M.; Klasson, A.; Pedersen, H.; Vahlberg, C.; Kall, P.-O.; Uvdal, K. High proton relaxivity for gadolinium oxide nanoparticles. MAGMA 2006, 19, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Baek, M.J.; Choi, E.S.; Woo, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, T.J.; Jung, J.C.; Chae, K.S.; Chang, Y.; Lee, G.H. Paramagnetic ultrasmall gadolinium oxide nanoparticles as advanced T-1 MR1 contrast agent: Account for large longitudinal relaxivity, optimal particle diameter, and in vivo T-1 MR images. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3663–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Park, J.Y.; Kattel, K.; Bony, B.A.; Heo, W.C.; Jin, S.; Park, J.W.; Chang, Y.; Do, J.Y.; Chae, K.S.; et al. A T-1, T-2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-fluorescent imaging (FI) by using ultrasmall mixed gadolinium-europium oxide nanoparticles. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 2361–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.R.; Baeck, J.S.; Chang, Y.; Bae, J.E.; Chae, K.S.; Lee, G.H. Ligand-size dependent water proton relaxivities in ultrasmall gadolinium oxide nanoparticles and in vivo T-1 MR images in a 1.5 T MR field. Phy. Chem. Chem. Phy. 2014, 16, 19866–19873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.W.; Kim, C.R.; Baeck, J.S.; Chang, Y.; Kim, T.J.; Bae, J.E.; Chaed, K.S.; Lee, G.H. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and cleaved-BSA conjugated ultrasmall Gd2O3 nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and application to MRI contrast agents. Colloid. Surf. A 2014, 450, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Ho, S.L.; Tegafaw, T.; Cha, H.; Chang, Y.; Oh, I.T.; Yaseen, A.M.; Marasini, S.; Ghazanfari, A.; Yue, H.; et al. Stable and non-toxic ultrasmall gadolinium oxide nanoparticle colloids (coating material = polyacrylic acid) as high-performance T-1 magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 3189–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.L.; Cha, H.; Oh, I.T.; Jung, K.-H.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Miao, X.; Tegafaw, T.; Ahmad, M.Y.; Chae, K.S.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging, gadolinium neutron capture therapy, and tumor cell detection using ultrasmall Gd2O3 nanoparticles coated with polyacrylic acid-rhodamine B as a multifunctional tumor theragnostic agent. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 12653–12665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Xu, W.; Cha, H.; Chang, Y.; Oh, I.T.; Chae, K.S.; Tegafaw, T.; Ho, S.L.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, G.H. Ultrasmall Gd2O3 nanoparticles surface-coated by polyacrylic acid (PAA) and their PAA-size dependent relaxometric properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 477, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Marasini, S.; Ahmad, M.Y.; Ho, S.L.; Cha, H.; Liu, S.; Jang, Y.J.; Tegafaw, T.; Ghazanfari, A.; Miao, X.; et al. Carbon-coated ultrasmall gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3@C) nanoparticles: Application to magnetic resonance imaging and fluorescence properties. Colloid. Surf. A 2020, 586, 124261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahren, M.; Selegard, L.; Klasson, A.; Soderlind, F.; Abrikossova, N.; Skoglund, C.; Bengtsson, T.; Engstrom, M.; Kall, P.-O.; Uvdal, K. Synthesis and characterization of PEGylated Gd2O3 nanoparticles for MRI contrast enhancement. Langmuir 2010, 26, 5753–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duc, G.; Miladi, I.; Alric, C.; Mowat, P.; Braeuer-Krisch, E.; Bouchet, A.; Khalil, E.; Billotey, C.; Janier, M.; Lux, F.; et al. Toward an image-guided microbeam radiation therapy using gadolinium-based nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9566–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lux, F.; Mignot, A.; Mowat, P.; Louis, C.; Dufort, S.; Bernhard, C.; Denat, F.; Boschetti, F.; Brunet, C.; Antoine, R.; et al. Ultrasmall rigid particles as multimodal probes for medical applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 12299–12303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faucher, L.; Tremblay, M.; Lagueux, J.; Gossuin, Y.; Fortin, M.-A. Rapid synthesis of PEGylated ultrasmall gadolinium oxide nanoparticles for cell labeling and tracking with MRI. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2012, 4, 4506–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viger, M.L.; Sankaranarayanan, J.; de Gracia Lux, C.; Chan, M.; Almutairi, A. Collective activation of MRI agents via encapsulation and disease-triggered release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7847–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Tan, W.; Talham, D.R. Size-dependent MRI relaxivity and dual imaging with Eu0.2Gd0.8PO4 center dot H2O nanoparticles. Langmuir 2014, 30, 5873–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chandrasekharan, P.; Liu, X.-L.; Yang, Y.; Lv, Y.-B.; Yang, C.-T.; Ding, J. Manipulating the surface coating of ultra-small Gd2O3 nanoparticles for improved T-1-weighted MR imaging. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdatkhah, P.; Hosseini, H.R.M.; Khodaei, A.; Montazerabadi, A.R.; Irajirad, R.; Oghabian, M.A.; Delavari, H.H. Rapid microwave-assisted synthesis of PVP-coated ultrasmall gadolinium oxide nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging. Chem. Phys. 2015, 453, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufort, S.; Le Duc, G.; Salome, M.; Bentivegna, V.; Sancey, L.; Brauer-Krisch, E.; Requardt, H.; Lux, F.; Coll, J.-L.; Perriat, P.; et al. The high radiosensitizing efficiency of a trace of gadolinium-based nanoparticles in tumors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Lu, T.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, S.; Lu, Q.; Yang, L.; Tan, F.; Li, J.; Li, N. Glutathione-mediated clearable nanoparticles based on ultrasmall Gd2O3 for MSOT/CT/MR imaging guided photothermal/radio combination cancer therapy. Mol. Pharmaceut. 2019, 16, 3489–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bony, B.A.; Miller, H.A.; Tarudji, A.W.; Gee, C.C.; Sarella, A.; Nichols, M.G.; Kievit, F.M. Ultrasmall mixed Eu-Gd oxide nanoparticles for multimodal fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging of passive accumulation and retention in TBI. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16220–16227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.J.J.; Oakden, W.; Stanisz, G.J.; Prosser, R.S.; van Veggel, F.C.J.M. Size-tunable, ultrasmall NaGdF4 nanoparticles: Insights into their T-1 MRI contrast enhancement. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 3714–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Feng, W.; Yang, T.; Yi, T.; Li, F. Upconversion luminescence imaging of cells and small animals. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 2033–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Zhang, S.; Bu, W.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Xiao, Q.; Ni, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, L.; Peng, W.; et al. Ultrasmall NaGdF4 nanodots for efficient MR angiography and atherosclerotic plaque imaging. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 3867–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, D.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Wu, R.; Liu, J.; Yi, M.; Wang, J.; Yao, Z.; Bu, W.; et al. Integrating anatomic and functional dual mode magnetic resonance imaging: Design and applicability of a bifunctional contrast agent. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3783–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Employing tryptone as a general phase transfer agent to produce renal clearable nanodots for bioimaging. Small 2015, 11, 3676–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Ding, L.; Liu, L.; Abualrejal, M.M.A.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z. Renal-clearable hyaluronic acid functionalized NaGdF4 nanodots with enhanced tumor accumulation. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 13872–13878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Renal clearable peptide functionalized NaGdF4 nanodots for high-efficiency tracking orthotopic colorectal tumor in mouse. Mol. Pharmaceut. 2017, 14, 3134–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Peptide-functionalized NaGdF4 nanoparticles for tumor-targeted magnetic resonance imaging and effective therapy. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 17093–17100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Luo, L.; Feng, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Shi, C.; Meng, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, H. Gadolinium-rose bengal coordination polymer nanodots for MR-/Fluorescence-image-guided radiation and photodynamic therapy. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2000377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassa, C.; Shaw, S.Y.; Weissleder, R. Dextran-coated iron oxide nanoparticles: A versatile platform for targeted molecular imaging, molecular diagnostics, and therapy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, X.Y.; Sena-Torralba, A.; Alvarez-Diduk, R.; Muthoosamy, K.; Merkoci, A. Nanomaterials for nanotheranostics: Tuning their properties according to disease needs. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 2585–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzin, A.; Etesami, S.A.; Quint, J.; Memic, A.; Tamayol, A. Magnetic nanoparticles in cancer therapy and diagnosis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1901058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardzinski, B.J.; Schmithorst, V.J.; Holland, S.K.; Boivin, G.P.; Imagawa, T.; Watanabe, S.; Lewis, J.M.; Hirsch, R. MR imaging of murine arthritis using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide particles. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2001, 19, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, C.; Chang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, F.; Gao, X. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle for T-2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 28959–28966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Lee, N.; Kim, H.; An, K.; Park, Y.I.; Choi, Y.; Shin, K.; Lee, Y.; Kwon, S.G.; Na, H.B.; et al. Large-scale synthesis of uniform and extremely small-sized iron oxide nanoparticles for high-resolution T-1 magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12624–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chevallier, P.; Ramrup, P.; Biswas, D.; Vuckovich, D.; Fortin, M.-A.; Oh, J.K. Mussel-inspired multidentate block copolymer to stabilize ultrasmall superparamagnetic Fe3O4 for magnetic resonance imaging contrast enhancement and excellent colloidal stability. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 7100–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Cho, S.H.; Seong, H. Multifunctional ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as a theranostic agent. Colloid. Surf. A 2017, 520, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromsdorf, U.I.; Bruns, O.T.; Salmen, S.C.; Beisiegel, U.; Weller, H. A highly effective, nontoxic T-1 MR contrast agent based on ultrasmall pegylated iron oxide nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 4434–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangijzegem, T.; Stanicki, D.; Panepinto, A.; Socoliuc, V.; Vekas, L.; Muller, R.N.; Laurent, S. Influence of experimental parameters of a continuous flow process on the properties of very small iron oxide nanoparticles (VSION) designed for T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.Z.; Ma, X.; Chen, T.; Zhang, L.e.; Ren, W.; Xiang, L.; Wu, A. Silica-coated super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONPs): A new type contrast agent of T-1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 5172–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, H.; Shi, X. Zwitterion-coated ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles for enhanced T-1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 7267–7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Bruns, O.T.; Kaul, M.G.; Hansen, E.C.; Barch, M.; Wisniowska, A.; Chen, O.; Chen, Y.; Li, N.; Okada, S.; et al. Exceedingly small iron oxide nanoparticles as positive MRI contrast agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2325–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Xiang, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zeng, W.; Liu, K.; Jin, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, B. Albumin-constrained large-scale synthesis of renal clearable ferrous sulfide quantum dots for T-1-Weighted MR imaging and phototheranostics of tumors. Biomaterials 2020, 255, 120186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, R.; Cai, Z.; Ren, B.W.; Li, A.; Lin, H.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Shan, H.; Ai, H.; Gao, J. Biodegradable and renal-clearable hollow porous iron oxide nanoboxes for in vivo imaging. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 7950–7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, J.; Yan, Y.; Li, J.; Shen, M.; Zhang, G.; Mignani, S.; Shi, X. RGD- functionalized ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles for targeted T-1-weighted MR imaging of gliomas. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 14538–14546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; He, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Gram-scale synthesis of coordination polymer nanodots with renal clearance properties for cancer theranostic applications. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Accurate monitoring of renal injury state through in vivo magnetic resonance imaging with ferric coordination polymer nanodots. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 4918–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Qiu, S.; Wen, L.; Wu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Biodegradable nanoagents with short biological half-life for SPECT/PAI/MRI multimodality imaging and PTT therapy of tumors. Small 2018, 14, 1702700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Skallberg, A.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Mei, X.; Uvdal, K. One-step synthesis of water-dispersible ultra-small Fe3O4 nanoparticles as contrast agents for T-1 and T-2 magnetic resonance imaging. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 2953–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Tang, J.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C. In vivo aggregation-induced transition between T-1 and T-2 relaxations of magnetic ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles in tumor microenvironment. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 3040–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]