Design and Activity of Novel Oxadiazole Based Compounds That Target Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase

Abstract

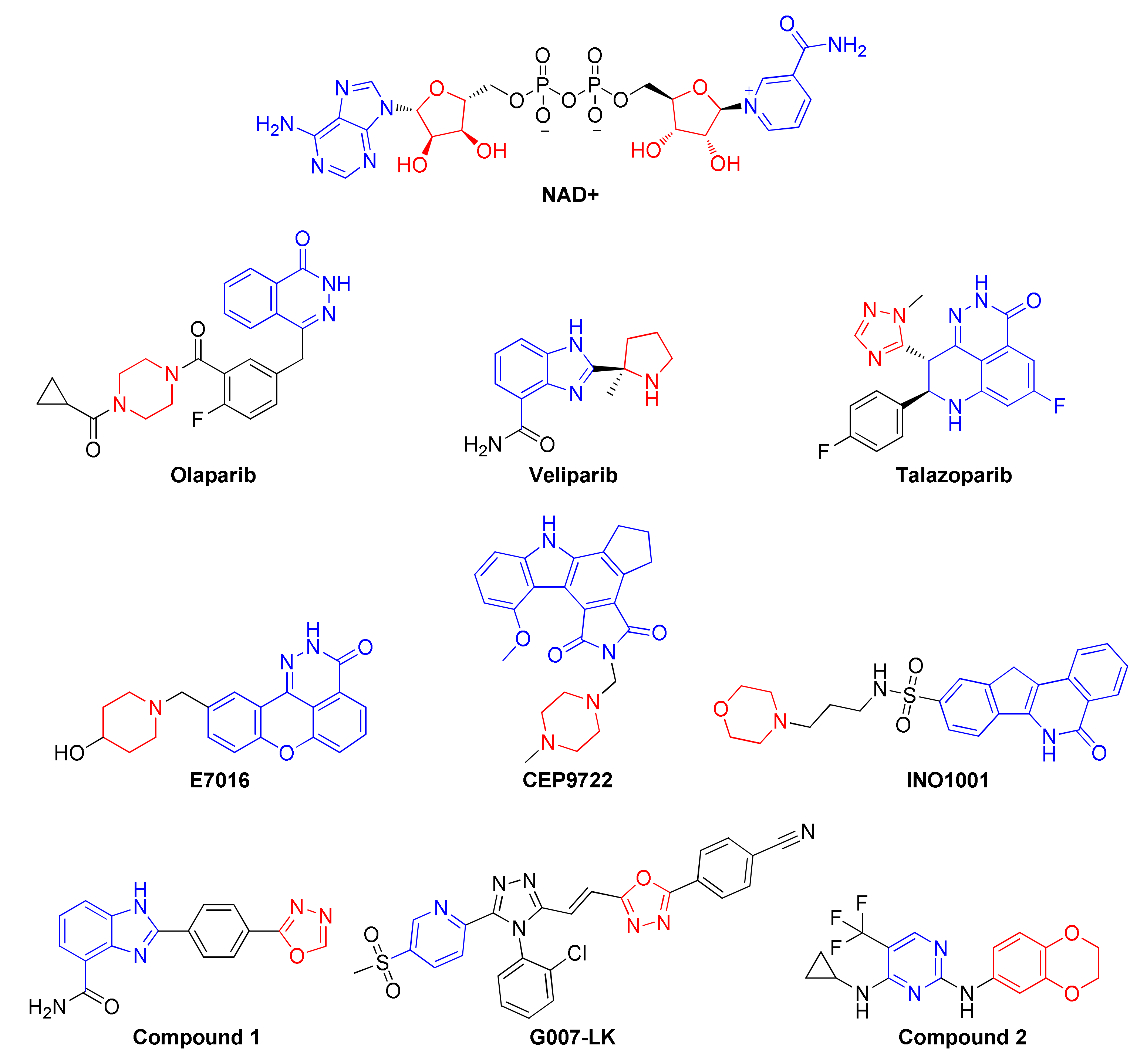

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

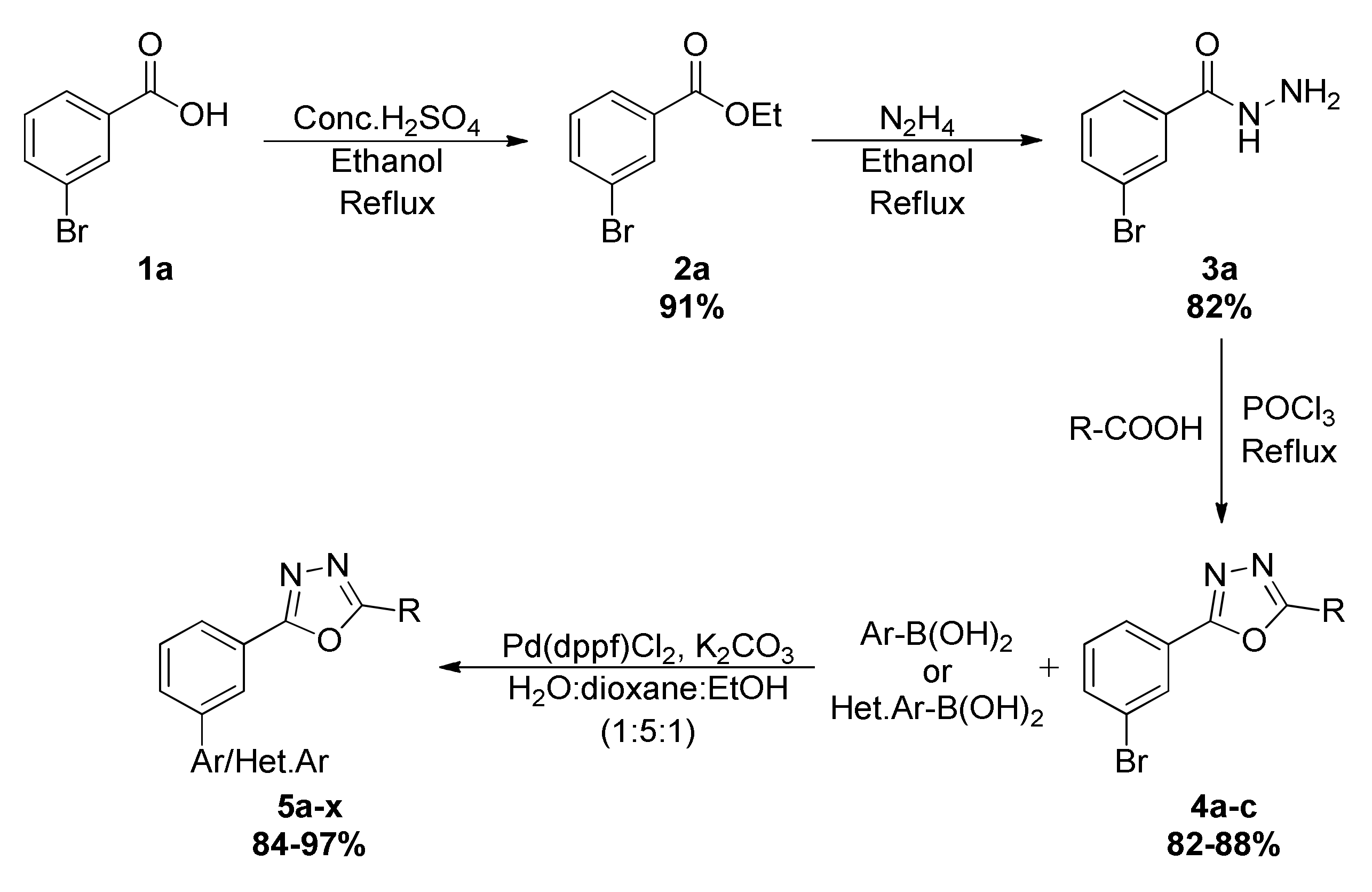

2.1. Chemical Synthesis of Newer Oxadiazoles

2.2. Efficacy of Oxadiazoles in Breast Cancer Cells

2.3. Newer Oxadiazoles Inhibited the Catalytical Activity of PARP1 In Vitro

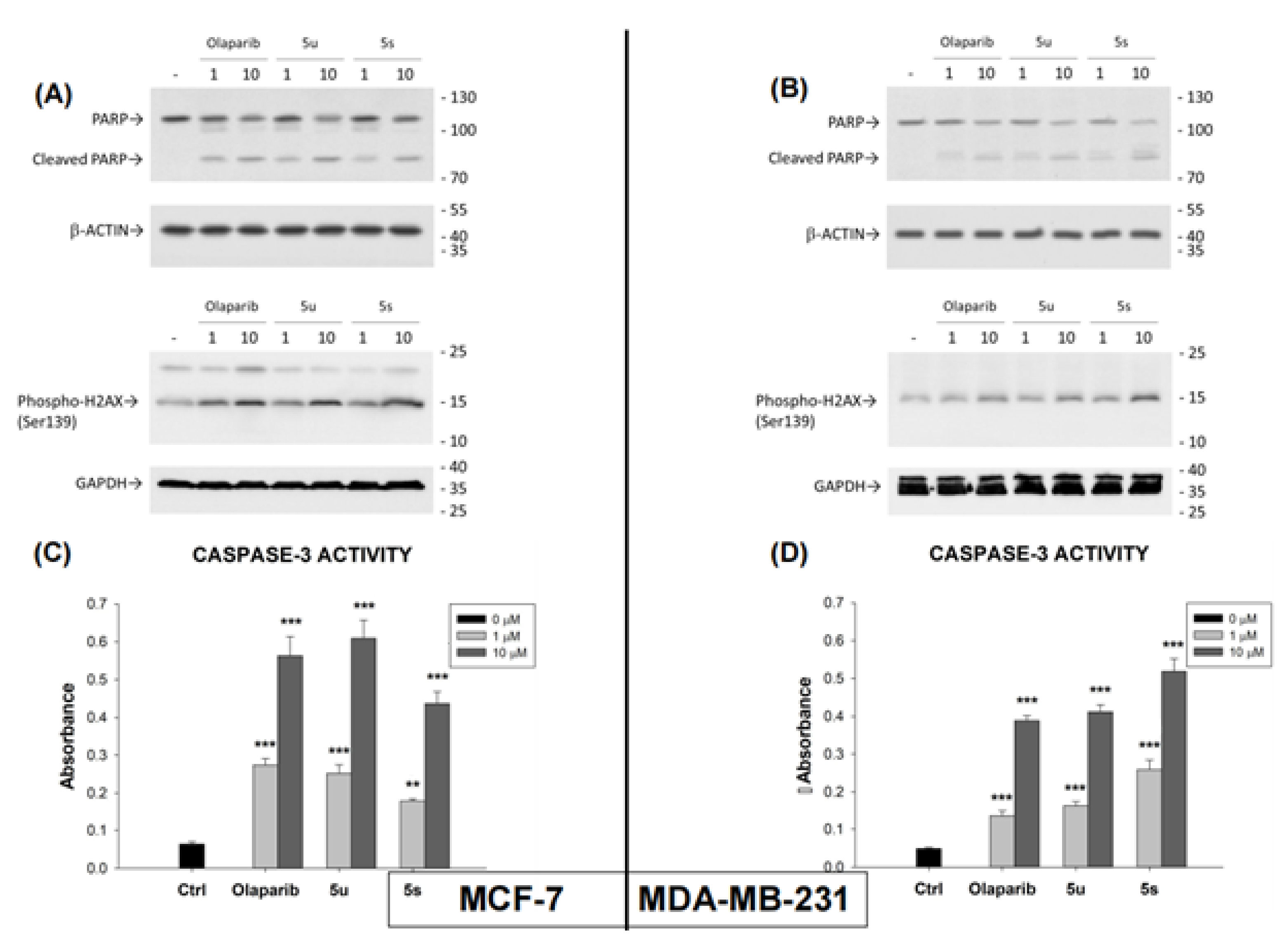

2.4. Compounds 5u and 5s Increased PARP1 Cleavage, Phospho-H2AX Levels and CPP32 (Caspase-3) Activation in Breast Cancer Cells

2.5. Compounds 5u and 5s Inhibit Oncogenicity and Decreases 3D Growth of Breast Cancer Cells

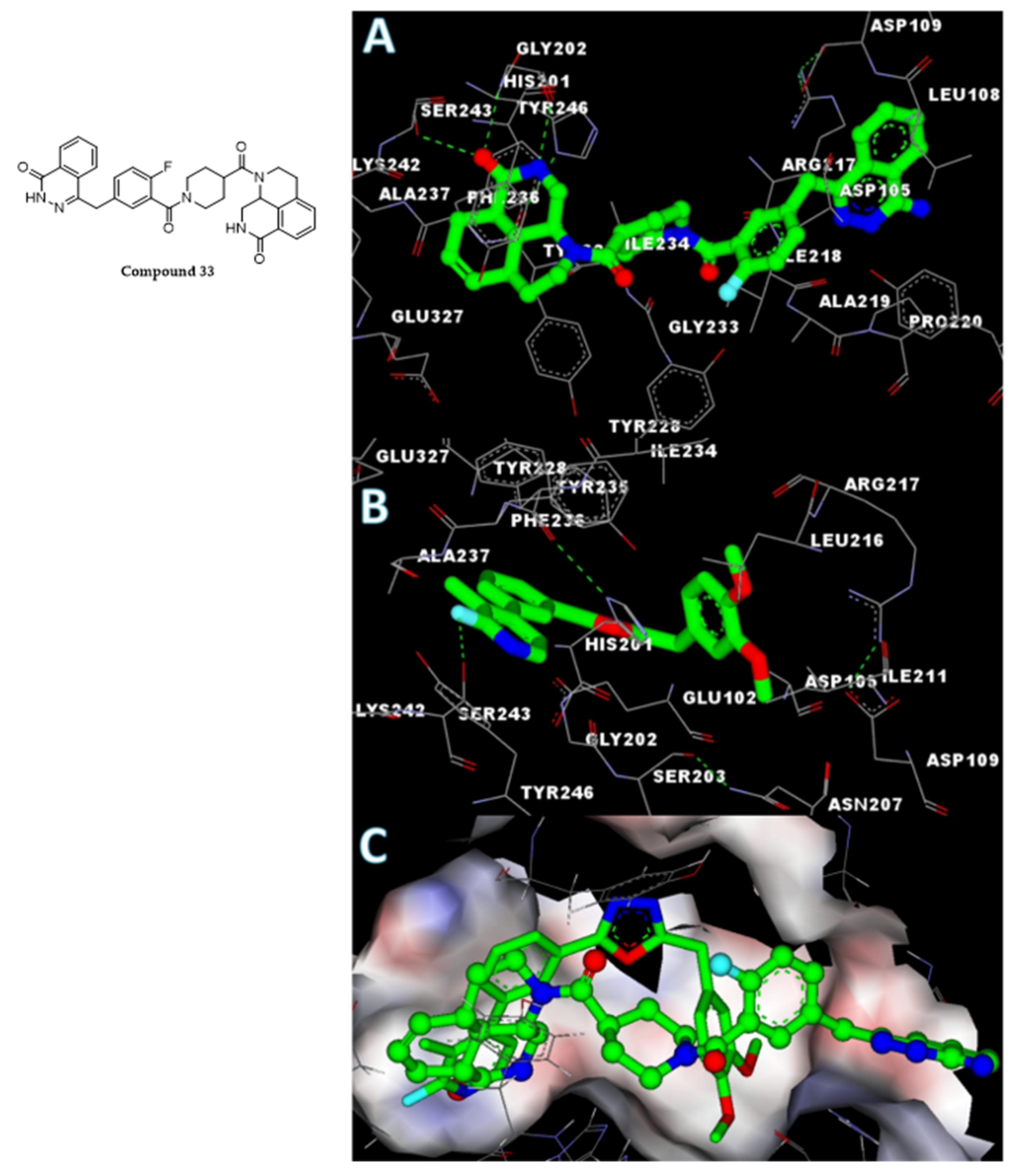

2.6. In Silico Analysis of the Interaction of Compound 5s with the PARP1 Catalytic Domain

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 2,5-Disubstituted-1,3,4-oxadiazole

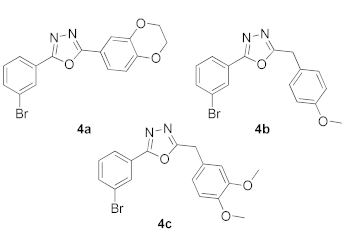

3.2. 2-(3-Bromophenyl)-5-(2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (4a)

3.3. 2-(3-Bromophenyl)-5-(4-methoxybenzyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (4b)

3.4. 2-(3-Bromophenyl)-5-(3,4-dimethoxybenzyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (4c)

3.5. 2-(3-(6-Chloro-5-methylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-5-(2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5a)

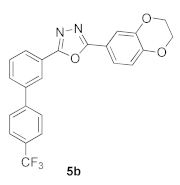

3.6. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(4′-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5b)

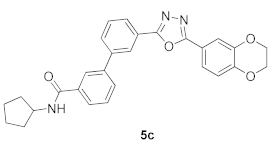

3.7. N-Cyclopentyl-3′-(5-(2,3-dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxamide (5c)

3.8. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3′-methoxy-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-yl)-1,3,4-oxadia-zole (5d)

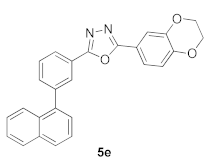

3.9. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3-(naphthalen-1-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5e)

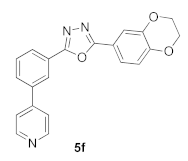

3.10. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5f)

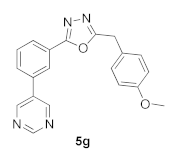

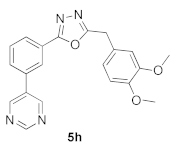

3.11. 2-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-5-(3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5g)

3.12. 2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl)-5-(3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5h)

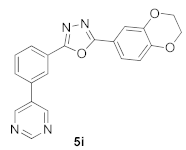

3.13. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3-(pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5i)

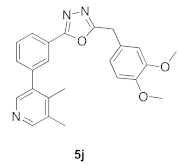

3.14. 2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl)-5-(3-(4,5-dimethylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5j)

3.15. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3-(4,5-dimethylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5k)

3.16. 2-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-5-(3-(pyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5l)

3.17. 2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl)-5-(3-(pyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5m)

3.18. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3-(pyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5n)

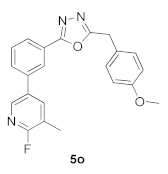

3.19. 2-(3-(6-Fluoro-5-methylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-5-(4-methoxybenzyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5o)

3.20. 2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl)-5-(3-(6-fluoro-5-methylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5p)

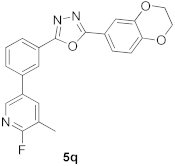

3.21. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3-(6-fluoro-5-methylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5q)

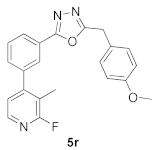

3.22. 2-(3-(2-Fluoro-3-methylpyridin-4-yl)phenyl)-5-(4-methoxybenzyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5r)

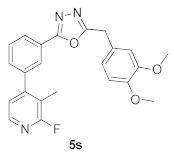

3.23. 2-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl)-5-(3-(2-fluoro-3-methylpyridin-4-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5s)

3.24. 2-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-5-(3-(2-fluoro-3-methylpyridin-4-yl)phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole (5t)

3.25. 3′-(5-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carbaldehyde (5u)

3.26. 3′-(5-(2,3-Dihydrobenzo[b][1,4]dioxin-6-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carbal-dehyde (5v)

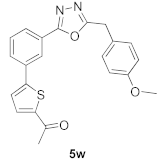

3.27. 1-(5-(3-(5-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)thiophen-2-yl)ethanone (5w)

3.28. 1-(5-(3-(5-(3,4-Dimethoxybenzyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)phenyl)thiophen-2-yl)ethanone (5x)

3.29. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 Cell Viability Assay

3.30. Assay of PARP Activity

3.31. Western Blot Analysis

3.32. Caspase-3 Activity Assay

3.33. Foci Formation Assay

3.34. Molecular Docking Analysis

3.35. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Economopoulou, P.; Dimitriadis, G.; Psyrri, A. Beyond BRCA: New hereditary breast cancer susceptibility genes. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2015, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, M.K.; Chen, A.P. PARP inhibitor treatment in ovarian and breast cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2011, 35, 7–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bryant, H.E.; Schultz, N.; Thomas, H.D.; Parker, K.M.; Flower, D.; Lopez, E.; Kyle, S.; Meuth, M.; Curtin, N.J.; Helleday, T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005, 434, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.Y.; Rahman, S.; Sparano, J.A. Perspectives on PARP inhibitors as pharmacotherapeutic strategies for breast cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2021, 22, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Nishimura, M.; Onoe, T.; Sakai, H.; Urakawa, Y.; Onda, T.; Yaegashi, N. PARP inhibitors for BRCA wild type ovarian cancer; gene alterations, homologous recombination deficiency and combination therapy. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 49, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, R.; Kraus, W.L. The PARP side of the nucleus: Molecular actions, physiological outcomes, and clinical targets. Mol. Cell. 2010, 39, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morales, J.; Li, L.; Fattah, F.J.; Dong, Y.; Bey, E.A.; Patel, M.; Gao, J.; Boothman, D.A. Review of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mechanisms of action and rationale for targeting in cancer and other diseases. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2014, 24, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pandya, K.G.; Patel, M.R.; Lau-Cam, C.A. Comparative study of the binding characteristics to and inhibitory potencies towards PARP and in vivo antidiabetogenic potencies of taurine, 3-aminobenzamide and nicotinamide. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010, 17 (Suppl. S1), S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fongmoon, D.; Shetty, A.K.; Basappa; Yamada, S.; Sugiura, M.; Kongtawelert, P.; Sugahara, K. Chondroitinase-mediated degradation of rare 3-O-sulfated glucuronic acid in functional oversulfated chondroitin sulfate K and E. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 21, 36895–36904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nirvanappa, A.C.; Mohan, C.D.; Rangappa, S.; Ananda, H.; Sukhorukov, A.Y.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Sundaram, M.S.; Nayaka, S.C.; Girish, K.S.; Chinnathambi, A.; et al. Novel Synthetic Oxazines Target NF-κB in Colon Cancer In Vitro and Inflammatory Bowel Disease In Vivo. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCann, K.E. Advances in the use of PARP inhibitors for BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer: Talazoparib. Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 1707–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henneman, L.; van Miltenburg, M.H.; Michalak, E.M.; Braumuller, T.M.; Jaspers, J.E.; Drenth, A.P.; de Korte-Grimmerink, R.; Gogola, E.; Szuhai, K.; Schlicker, A.; et al. Selective resistance to the PARP inhibitor olaparib in a mouse model for BRCA1-deficient metaplastic breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8409–8414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russo, A.L.; Kwon, H.C.; Burgan, W.E.; Carter, D.; Beam, K.; Weizheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Slusher, B.S.; Chakravarti, A.; Tofilon, P.J.; et al. In vitro and in vivo radiosensitization of glioblastoma cells by the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor E7016. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Awada, A.; Campone, M.; Varga, A.; Aftimos, P.; Frenel, J.S.; Bahleda, R.; Gombos, A.; Bourbouloux, E.; Soria, J.C. An open-label, dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of CEP-9722 (a PARP-1 and PARP-2 inhibitor) in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with advanced solid tumors. Anticancer Drugs 2016, 27, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paldino, E.; Cardinale, A.; D’Angelo, V.; Sauve, I.; Giampà, C.; Fusco, F.R. Selective Sparing of Striatal Interneurons after Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 Inhibition in the R6/2 Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Front. Neuroanat. 2017, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tong, Y.; Bouska, J.J.; Ellis, P.A.; Johnson, E.F.; Leverson, J.; Liu, X.; Marcotte, P.A.; Olson, A.M.; Osterling, D.J.; Przytulinska, M.; et al. Synthesis and evaluation of a new generation of orally efficacious benzimidazole-based poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibitors as anticancer agents. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6803–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, B.S.; Swamy, S.N.; Tejesvi, M.V.; Basappa; Sarala, G.; Gaonkar, S.L.; Naveen, S.; Prasad, J.S.; Rangappa, K.S. Synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial and single crystal X-ray crystallographic studies of some new sulfonyl, 4-chloro phenoxy benzene and dibenzoazepine substituted benzamides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 41, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Mohan, C.D.; Basappa, S.; Rangappa, S.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alahmadi, T.A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Kumar, A.P.; Sethi, G.; Ahn, K.S.; et al. The IκB Kinase Inhibitor ACHP Targets the STAT3 Signaling Pathway in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Voronkov, A.; Holsworth, D.D.; Waaler, J.; Wilson, S.R.; Ekblad, B.; Perdreau-Dahl, H.; Dinh, H.; Drewes, G.; Hopf, C.; Morth, J.P.; et al. Structural basis and SAR for G007-LK, a lead stage 1,2,4-triazole based specific tankyrase 1/2 inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3012–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Bakas, N.A.; Vamos, M.; Chaikuad, A.; Limpert, A.S.; Wimer, C.D.; Brun, S.N.; Lambert, L.J.; Tautz, L.; Celeridad, M.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of an Orally Active Dual-Specific ULK1/2 Autophagy Inhibitor that Synergizes with the PARP Inhibitor Olaparib for the Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 14609–14625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malojirao, V.H.; Girimanchanaika, S.S.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Sherapura, A.; Dukanya; Metri, P.K.; Vigneshwaran, V.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Rangappa, S.; et al. Novel 1,3,4-oxadiazole Targets STAT3 Signaling to Induce Antitumor Effect in Lung Cancer. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dukanya; Shanmugam, M.K.; Rangappa, S.; Metri, P.K.; Mohan, S.; Basappa; Rangappa, K.S. Exploring the newer oxadiazoles as real inhibitors of human SIRT2 in hepatocellular cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, C.D.; Anilkumar, N.C.; Rangappa, S.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Mishra, S.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Sethi, G.; Kumar, A.P.; et al. Novel 1,3,4-Oxadiazole Induces Anticancer Activity by Targeting NF-κB in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pandey, V.; Wang, B.; Mohan, C.D.; Raquib, A.R.; Rangappa, S.; Srinivasa, V.; Fuchs, J.E.; Girish, K.S.; Zhu, T.; Bender, A.; et al. Discovery of a small-molecule inhibitor of specific serine residue BAD phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E10505–E10514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, B.; Chong, Q.Y.; Pandey, V.; Guo, Z.; Chen, R.M.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Kumar, A.P.; et al. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) potentiates MEK1/2 inhibition in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogenesis 2019, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusha, S.; Mohan, C.D.; Ananda, H.; Baburajeev, C.P.; Rangappa, S.; Mathai, J.; Fuchs, J.E.; Li, F.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Bender, A.; et al. Adamantyl-tethered-biphenylic compounds induce apoptosis in cancer cells by targeting Bcl homologs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangappa, K.S.; Basappa. New cholinesterase inhibitors: Synthesis and structure–activity relationship studies of 1,2-benzisoxazole series and novel imidazolyl-d2-isoxazolines. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basappa; Kavitha, C.V.; Rangappa, K.S. Simple and an efficient method for the synthesis of 1-[2-dimethylamino-1-(4-methoxy-phenyl)-ethyl]-cyclohexanol hydrochloride: (+/−) venlafaxine racemic mixtures. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 3279–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M.; Lindahl, T. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) formation in DNA repair. Nature 1992, 356, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilardini Montani, M.S.; Prodosmo, A.; Stagni, V.; Merli, D.; Monteonofrio, L.; Gatti, V.; Gentileschi, M.P.; Barilà, D.; Soddu, S. ATM-depletion in breast cancer cells confers sensitivity to PARP inhibition. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 32, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deepti Sharma, L.D.F.; Sivaraman Padavattan, C.R.; Geifman-Shochat, S.; Liu, C.F.; Davey, C.A. PARP1 exhibits enhanced association and catalytic efficiency with γH2A.X-nucleosome. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, C.D.; Srinivasa, V.; Rangappa, S.; Mervin, L.; Mohan, S.; Paricharak, S.; Baday, S.; Li, F.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Chinnathambi, A.; et al. Trisubstituted-Imidazoles Induce Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer Cells by Targeting the Oncogenic PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mah, L.J.; El-Osta, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. γH2AX: A sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia 2010, 24, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datta, R.; Banach, D.; Kojima, H.; Talanian, R.V.; Alnemri, E.S.; Wong, W.W.; Kufe, D.W. Activation of the CPP32 protease in apoptosis induced by 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine and other DNA-damaging agents. Blood 1996, 88, 1936–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; Redon, C.E.; Reinhold, W.C.; Chen, A.P.; Fogli, L.K.; Holbeck, S.L.; Parchment, R.E.; Hollingshead, M.; Tomaszewski, J.E.; et al. Phosphorylated fraction of H2AX as a measurement for DNA damage in cancer cells and potential applications of a novel assay. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Qi, L.; Li, L.; Li, Y. The caspase-3/GSDME signal pathway as a switch between apoptosis and pyroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, P.H.T.; Nguyen, T.D.T.; Tran, H.T.; Nguyen, Y.N.; Doan, M.T.; Nguyen, P.H.; Lien, G.T.K.; To, D.C.; Tran, M.H. Cytotoxic components from the leaves of Erythrophleumfordii induce human acute leukemia cell apoptosis through caspase 3 activation and PARP cleavage. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 31, 127673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, M.; Hakem, R.; Soengas, M.S.; Duncan, G.S.; Shahinian, A.; Kägi, D.; Hakem, A.; McCurrach, M.; Khoo, W.; Kaufman, S.A.; et al. Essential contribution of caspase 3/CPP32 to apoptosis and its associated nuclear changes. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ye, N.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, T.; Song, Z.; He, J.X.; Huan, X.J.; Song, S.S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ding, J.; et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a series of benzo[de][1,7]naphthyridin-7(8H)-ones bearing a functionalized longer chain appendage as novel PARP1 inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2885–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikkegowda, P.; Pookunoth, B.C.; Bovilla, V.R.; Veeresh, P.M.; Leihang, Z.; Thippeswamy, T.; Padukudru, M.A.; Hathur, B.; Kanchugarakoppal, R.S.; Madhunapantula, S.V. Design, Synthesis, Characterization, and Crystal Structure Studies of Nrf2 Modulators for Inhibiting Cancer Cell Growth In Vitro and In Vivo. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10054–10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, N.; Garg, M.; Mohan, C.D.; Fuchs, J.E.; Rangappa, S.; Anusha, S.; Swaroop, T.R.; Rakesh, K.S.; Kanojia, D.; Madan, V.; et al. Synthesis of 1,2-benzisoxazole tethered 1,2,3-triazoles that exhibit anticancer activity in acute myeloid leukemia cell lines by inhibiting histone deacetylases, and inducing p21 and tubulin acetylation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 6157–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Oguz, G.; Lee, W.C.; Lee, P.L.; Ghosh, K.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Lobie, P.E.; Ehmsen, S.; Ditzel, H.J.; et al. EZH2-mediated PP2A inactivation confers resistance to HER2-targeted breast cancer therapy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, V.; Tan, Y.Q.; Wu, M.M.; Ma, L.; Zhu, T.; Lobie, P.E.; Pandey, V. Long non-coding RNAs in recurrent ovarian cancer: Theranostic perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2021, 502, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basappa, B.; Chumadathil Pookunoth, B.; Shinduvalli Kempasiddegowda, M.; Knchugarakoppal Subbegowda, R.; Lobie, P.E.; Pandey, V. Novel Biphenyl Amines Inhibit Oestrogen Receptor (ER)-α in ER-Positive Mammary Carcinoma Cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh, H.M.; Chiou, Y.S.; Chong, Q.Y.; Chen, R.M.; Rangappa, K.S.; Ma, L.; Zhu, T.; Kumar, A.P.; Pandey, V.; Basappa; et al. Inhibition of TFF3 Enhances Sensitivity-and Overcomes Acquired Resistance-to Doxorubicin in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Mammary Carcinoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Basappa; Sugahara, K.; Thimmaiah, K.N.; Bid, H.K.; Houghton, P.J.; Rangappa, K.S. Anti-tumor activity of a novel HS-mimetic-vascular endothelial growth factor binding small molecule. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Ar-B(OH)2/ Het.Ar-B(OH)2 | Structures of (4a–c) |

|---|---|

| (6-chloro-5-methylpyridin-3-yl)boronic acid |  |

| (4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)boronic acid | |

| (3-(cyclopentylcarbamoyl)phenyl)boronic acid | |

| (3-methoxyphenyl)boronic acid | |

| naphthalen-1-ylboronic acid | |

| pyridin-4-ylboronic acid | |

| pyrimidin-5-ylboronic acid | |

| (4,5-dimethylpyridin-3-yl)boronic acid | |

| pyridin-3-ylboronic acid | |

| (6-fluoro-5-methylpyridin-3-yl)boronic acid | |

| (2-fluoro-3-methylpyridin-4-yl)boronic acid | |

| (3-formylphenyl)boronic acid | |

| (5-acetylthiophen-2-yl)boronic acid |

| Product 5a–x | IC50 (μM) | Product 5a–x | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 160.00 |  | 31.53 |

| 205.10 |  | 21.88 |

| 160.90 |  | 43.47 |

| 345.00 |  | 33.22 |

| 74.80 |  | 76.40 |

| >100 |  | 30.85 |

| 27.13 |  | 15.33 |

| 182.40 |  | 265.20 |

| 41.23 |  | 1.45 |

| 18.45 |  | 85.30 |

| 84.00 |  | 23.14 |

| 25.04 |  | >100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vishwanath, D.; Girimanchanaika, S.S.; Dukanya, D.; Rangappa, S.; Yang, J.-R.; Pandey, V.; Lobie, P.E.; Basappa, B. Design and Activity of Novel Oxadiazole Based Compounds That Target Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase. Molecules 2022, 27, 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27030703

Vishwanath D, Girimanchanaika SS, Dukanya D, Rangappa S, Yang J-R, Pandey V, Lobie PE, Basappa B. Design and Activity of Novel Oxadiazole Based Compounds That Target Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase. Molecules. 2022; 27(3):703. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27030703

Chicago/Turabian StyleVishwanath, Divakar, Swamy S. Girimanchanaika, Dukanya Dukanya, Shobith Rangappa, Ji-Rui Yang, Vijay Pandey, Peter E. Lobie, and Basappa Basappa. 2022. "Design and Activity of Novel Oxadiazole Based Compounds That Target Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase" Molecules 27, no. 3: 703. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27030703