Abstract

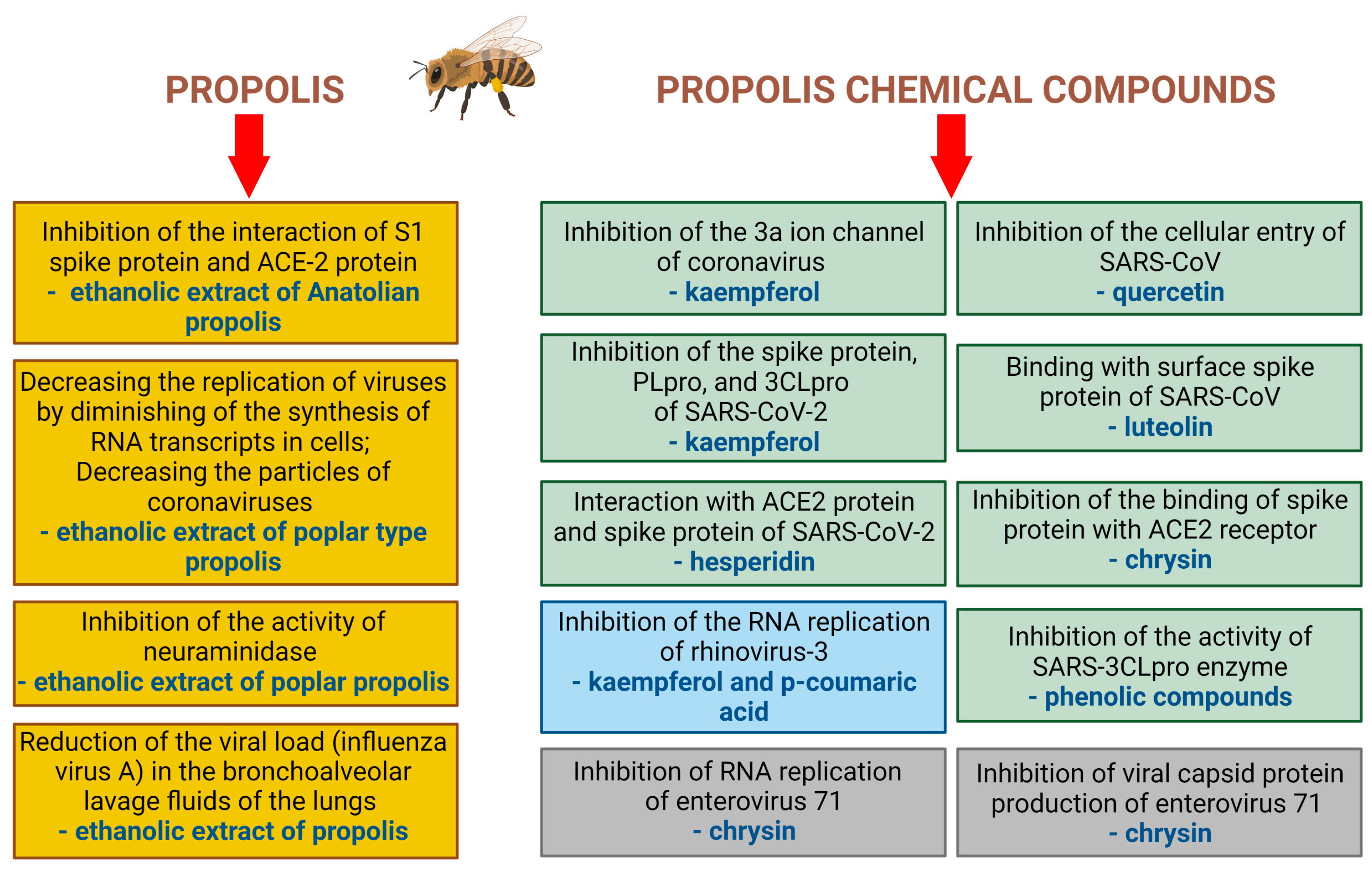

Propolis remains an interesting source of natural chemical compounds that show, among others, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities. Due to the growing incidence of respiratory tract infections caused by various pathogenic viruses, complementary methods of prevention and therapy supporting pharmacotherapy are constantly being sought out. The properties of propolis may be important in the prevention and treatment of respiratory tract diseases caused by viruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, influenza viruses, the parainfluenza virus and rhinoviruses. One of the main challenges in recent years has been severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), causing COVID-19. Recently, an increasing number of studies are focusing on the activity of various propolis preparations against SARS-CoV-2 as an adjuvant treatment for this infection. Propolis has shown a few key mechanisms of anti-SARS-CoV-2 action such as: the inhibition of the interaction of the S1 spike protein and ACE-2 protein; decreasing the replication of viruses by diminishing the synthesis of RNA transcripts in cells; decreasing the particles of coronaviruses. The anti-viral effect is observed not only with extracts but also with the single biologically active compounds found in propolis (e.g., apigenin, caffeic acid, chrysin, kaempferol, quercetin). Moreover, propolis is effective in the treatment of hyperglycemia, which increases the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections. The aim of the literature review was to summarize recent studies from the PubMed database evaluating the antiviral activity of propolis extracts in terms of prevention and the therapy of respiratory tract diseases (in vitro, in vivo, clinical trials). Based upon this review, it was found that in recent years studies have focused mainly on the assessment of the effectiveness of propolis and its chemical components against COVID-19. Propolis exerts wide-spectrum antimicrobial activities; thus, propolis extracts can be an effective option in the prevention and treatment of co-infections associated with diseases of the respiratory tract.

1. Introduction

Global epidemiological challenges have resulted in natural substances becoming increasingly important due to their wide availability and popularity. The increasing resistance to many anti-viral drugs and their low efficacy against viral diseases make it necessary to analyze the results of studies carried out to ascertain the therapeutic effects of natural substances such as propolis. Propolis has been used for medical purposes since ancient times. Propolis in various forms is a natural product that is widely accepted by patients around the world in various health situations. In traditional folk medicine, propolis has been used in the treatment of various diseases, particularly for anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, anti-fungal and anti-ulcer purposes. Moreover, propolis has long been used to improve health and prevent many diseases [1,2]. A number of studies demonstrated the popularity of propolis in the treatment of respiratory tract infections [3,4], alone or in combination with another immunomodulator such as Echinacea sp. [5].

Infectious diseases involving viral and bacterial respiratory pathogenic microorganisms have been shown to significantly impact lives and impart economic costs [6]. According to Ferkol et al. [7], it was observed that respiratory tract diseases such as infections of the respiratory tract, influenza and asthma caused the highest societal and economic burdens. One of the main challenges in recent years has been severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), causing COVID-19, with a calculated direct medical cost of USD 163.4 billion [8]. Therefore, there is a need to search for cheaper and more effective methods for the treatment of respiratory diseases. So far, the treatment of patients with COVID-19 is based on the use of many drugs, including antivirals, anti-inflammatory drugs, antibodies obtained from convalescent plasma, anticoagulants and monoclonal antibodies [9]. Pharmacological studies have demonstrated that propolis may exert synergistic effects when used with various groups of medicinal products such as antibiotics, antifungals and antiviral drugs. Furthermore, it is believed that propolis can lead to a reduction in the required doses of these drugs [10]. In addition to propolis, over 30 medicinal plant species used in the therapy of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been described (e.g., Forsythia suspensa (Thunb.) Vahl, Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Platycodon grandiflorum (Jacq.) A. DC., Nigella sativa L.) [11,12,13,14,15].

Recently, there has been an increase in the number of studies examining the various propolis preparation methods (extracts, liposomes) and their efficacy against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as an adjuvant treatment for this infection [6,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Therefore, this review aims to provide a summary of recent preclinical (in vitro and in vivo) and clinical studies on the role of propolis and its extracts in the prevention and treatment of viral respiratory diseases.

2. Methodology

We searched the PubMed database for scientific articles using the following search terms (keywords): “propolis”, “respiratory diseases”, “COVID-19”, “influenza viruses”, “parainfluenza virus”, “rhinoviruses”. We also collected information on clinical trials from the platform clinical.trial.gov.

In the PubMed database, 4259 publications about “propolis” are available; however only 228 publications are about the antiviral activity of propolis, including 130 articles from the last 10 years (2012–2022). In fact, publications relating to the use of “propolis” in “respiratory diseases” numbered only 25 between the years of 1976 to 2022 and only 18 between 2012 and 2022. With respect to the antiviral activity of “propolis” against “COVID-19”, the PubMed database contains 57 scientific papers published over a two-year period (from 2020 up to 2022). Specifically, 16 articles were published in 2020, 24 in 2021 and 17 in 2022. Most of these are review articles and studies using in vitro and animal models, with only a few studies (n = 8) having been carried out by in silico means. To date, the results of only three clinical studies are available in this database and one on the platform clinical.trial.gov. Moreover, with respect to the antiviral activity of propolis against influenza viruses, PubMed contains 11 publications, while only 2 publications relate to the effect of propolis on rhinoviruses. In short, we included publications from the last 10 years, but where it was necessary (in the absence of current research), previously published articles were cited. The discussion features publications pertaining to respiratory diseases. It should likewise be emphasized that the article by Serkedjiev et al., published in 1992, is not available in PubMed; however, it is often cited by other authors and as such has been included in the present review.

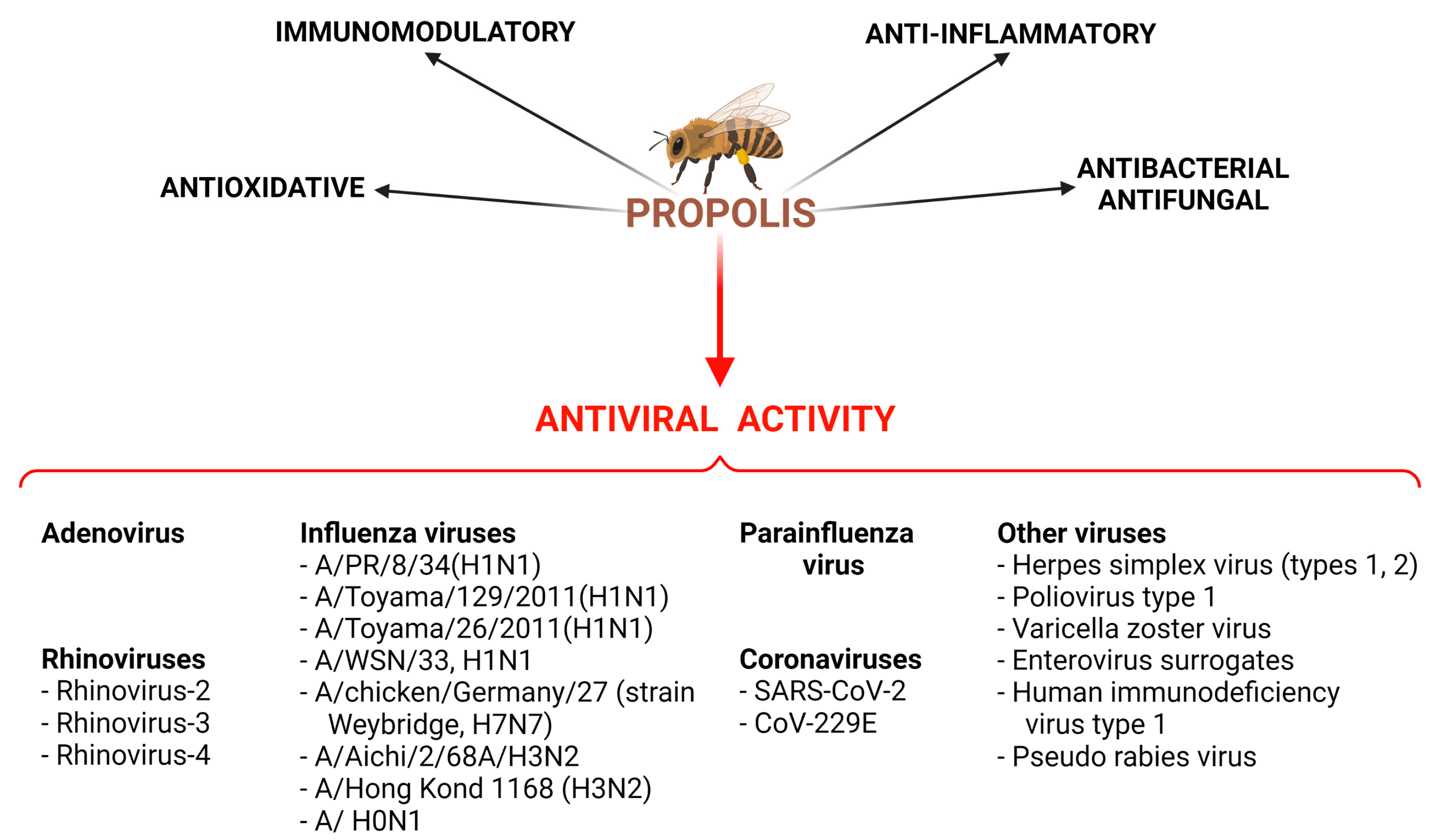

3. Progress in Studies of Propolis

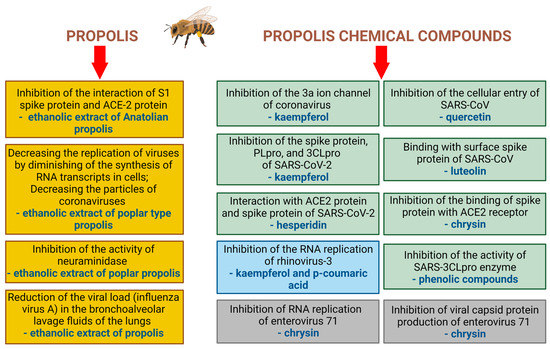

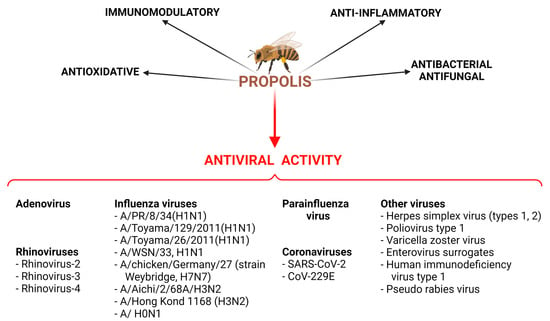

Many studies examined the anti-microbial activities of propolis, including not only antibacterial and antifungal properties [30,31,32] but also its antiviral activity. According to Yosri et al. [33], ethanolic extracts of propolis have anti-viral properties against the Herpes simplex virus (types 1 and 2) in vitro; however, only six such in vitro studies have been carried out. Moreover, extracts of propolis can exert activity against Poliovirus type 1, but the results of only two in vitro studies have been described. Yosri et al. [33] summarized the activity of propolis against the Varicella zoster virus (one study), Enterovirus surrogates (one study), the Influenza A virus H1N1 (two studies), human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (one study) and Pseudo Rabies Virus (one study). According to Münstedt [34], six randomized trials have been conducted in order to estimate the anti-viral activity of propolis; it was found that propolis was superior to a placebo against herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2 and the varicella zoster virus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Activities of propolis extracts and their natural chemical compounds demonstrated during in vitro and in vivo studies. Created with BioRender.com.

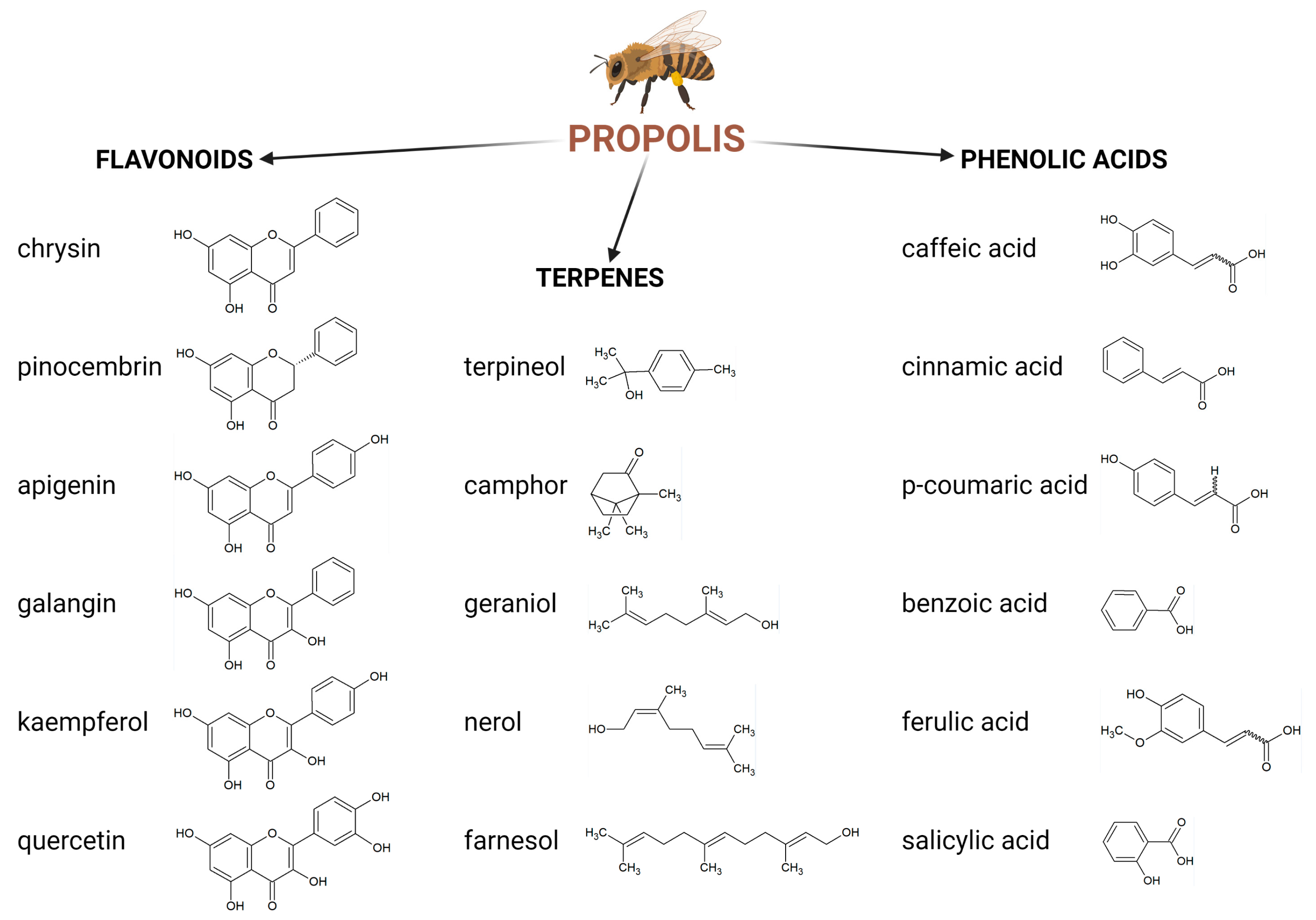

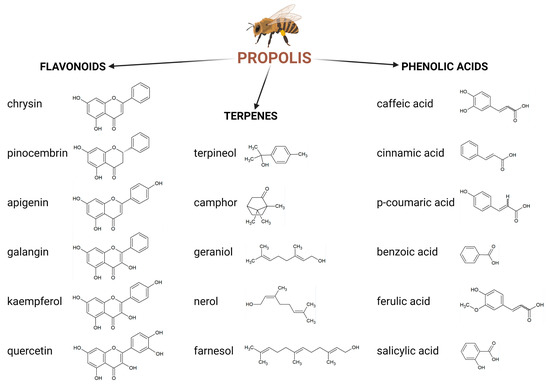

More studies have been conducted for single chemical compounds found in propolis and other plants. Anti-viral activity has been observed with phenolic compounds such as apigenin and kaempferol (against various types of the Influenza A virus) [35], acacetin, caffeic acid, chrysin, ferulic acid, fisetin, luteolin, p-coumaric acid and quercetin (against various types of the human rhinovirus) [36]. Progress has been made with regard to identifying the chemical compounds responsible for the pharmacologic and therapeutic effects found in propolis extracts (Figure 2). Ethanolic extracts from propolis may be of more interest because they contain many chemical compounds that can exert synergistic activity against various types of viruses. Several papers described that extracts from natural products are a source of complex matrices of bioactive metabolites, showing activity through synergy [31,32,37,38,39]. To date, over 800 chemical compounds have been detected in various types of propolis from different geographical areas [39]. Zullkiflee et al. [40] describe the main chemical composition of propolis and highlight compounds such as aromatic acids, alcohols, esters, fatty and aliphatic acids, flavonoids, microelements, sugars, vitamins and others.

Figure 2.

Main chemical compounds of propolis. Created with BioRender.com.

An increasing number of studies are focusing on the efficacy of using various propolis preparations (extracts, liposomes) against SARS-CoV-2 as an adjuvant treatment for this infection [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,40].

5. Propolis Activity against Influenza A Virus and Parainfluenza Virus

5.1. Preclinical Studies

There are four types of influenza viruses (A–D). However, only subtypes of the influenza A and B viruses cause seasonal epidemics of disease [62]. According to the WHO [63], these annual epidemics are estimated to cause approximately 3 to 5 million cases of serious disease and 650,000 deaths resulting from respiratory tract complications.

A study performed by Governa et al. [64] focused on the assessment of an 80% ethanolic extract of poplar propolis (containing the flavonoids galagin and pinocembrin) against a subtype of the H1N1 virus in vitro. They found that this extract (35 μg/mL) inhibited the activity of neuraminidase (IC50, 35.29 µg/mL), an enzyme involved in the viral lifecycle. Poplar propolis extract likewise possessed anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities.

A few years earlier, the water and the ethanolic extracts of Brazilian green propolis (200 mg/kg), 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid (3,4-diCQA, 50 mg/kg) and chlorogenic acid (50 mg/kg) were tested in Balb/c mice infected with the influenza A virus strain A/WSN/33 [65]. The investigators found that the propolis extract and 3,4-diCQA resulted in an increased survival rate in mice as well as the upregulation of the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; however, chlorogenic acid did not show these effects.

Urushisaki et al. [66] investigated the effects of Brazilian green propolis water extract on two influenza strains (A/WSN/33, H1N1) in vitro and found that this extract exerts cytoprotective effects. 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid (included in the extract) was the most active against the influenza viruses tested (EC50 = 81.1 μM) when compared with other active chemical compounds such as caffeoylquinic acids and caffeic acid. Chlorogenic acid showed the lowest antiviral activity and quinic acid was deemed ineffective.

Previously, it was shown that a 70% ethanolic extract of propolis exerted antiviral activity against the avian influenza virus A/chicken/Germany/27 (strain Weybridge, H7N7) in vitro [67]. Moreover, the ethanolic extract of Brazilian propolis at doses of 2 and 10 mg/kg administered three times daily to mice (DBA/2) infected by the influenza A/PR/8/34 virus prolonged the survival time of infected mice and improved the severity of influenza symptoms in these animals [68]. According to Serkedjieva et al. [69], it has been observed that the Et2O fraction of the ethanolic extract of propolis diminished the infectious activity of A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 in vitro at concentrations of 50 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL, respectively. Results cited by Serkedjieva et al. [69] suggest that propolis was also active against the H0N1 viral strain in vitro. Furthermore, kaempferol at a dose of 30 mg/kg prolonged the survival time of animals (BALF mice) after infection [35]. Moreover, apigenin, coumaric acid and kaempferol showed antiviral activity against strains such as A/PR/8/34(H1N1), A/Toyama/129/2011(H1N1), A/Toyama/26/2011(H1N1) in vitro when compared with other tested chemical compounds (i.e., artepillin C, chrysin, quercetin, rutin, benzoic acid, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid, trans-cinnamic acid). However, caffeic acid exerted activity against the A/Toyama/129/2011(H1N1) and A/Toyama/26/2011(H1N1) strains but not the A/PR/8/34(H1N1) strain in vitro [35]. Additionally, Serkedjieva et al. [69] showed that some synthetic constituents of propolis decreased the infectious activity of the influenza viruses A/Hong Kong/1/68 (H3N2) and A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) in vitro. Drago et al. [70] compared the antiviral activity of the hydroalcoholic extract from propolis. They found that the antiviral activity of Actichelated® propolis (in concentrations ranging from 0.032 to 0.128 g/l), in conjunction with galagin, was higher than that of the hydroalcoholic extract against the influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus and herpes virus type 1. Propolis also possesses antibacterial activity and does not show cytotoxic effects. Table 1 contains summary of the antiviral activity of propolis against respiratory viruses obtained in preclinical studies.

Table 1.

Summary of the antiviral activity of propolis against respiratory viruses obtained in n preclinical studies.

5.2. Clinical Trials

To date, there have been no published controlled clinical trials focusing on the evaluation of the efficacy of propolis preparations against infections caused by influenza viruses.

6. Activity against Human Rhinoviruses

6.1. Preclinical Studies

Upper respiratory tract infections are among the most common diseases in the world [71]. Human rhinoviruses, coronaviruses and respiratory syncytial viruses are responsible for infections of the upper respiratory tract not only in children but also in adults. It is estimated that they cause more than 50% of common colds [36]. According to the estimation of Jin et al. [71], the incident cases of upper respiratory tract infections numbered at approximately 17.2 billion in 2019. Despite the great burden to health, recently only one in vitro study investigated the activity of propolis in respiratory tract infections. Kwon et al. [36] outline that an 80% ethanolic extract of Brazilian propolis and its fractions obtained using hexane, chloroform and ethyl acetate exhibit antiviral activity against rhinovirus-4 with IC50 values ranging from 5.00 µg/mL (chloroform-soluble fraction) to 15.4 µg/mL (ethanolic extract). Kaempferol and chrysin were obtained from this ethanolic extract. Kaempferol showed the most antiviral activity against rhinovirus-2, with IC50 values of 7.3 µg/mL, while chrysin showed the most antiviral activity against rhinovirus-3 (IC50 = 17.3 µg/mL). Other natural chemical compounds found to be active against rhinovirus-2 include quercetin, luteolin and galagin. Moreover, kaempferol and p-coumaric acid inhibited the viral RNA replication levels of rhinovirus-3 in HeLa cells and reduced the penetration of the viruses into the cells [36].

6.2. Clinical Trials

With respect to clinical trials, the authors highlight the use of bee products in the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections in children [3]. The results of a double-blind clinical trial involving young patients ranging from 5 to 12 years of age with viral and bacterial tonsillopharyngitis showed that the administration of a complex product containing honey, royal jelly and propolis (20–40 mg/kg for 10 days) was beneficial in the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections [3]. Recently, Esposito et al. [72] performed a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial in order to assess the efficacy of an oral propolis spray (M.E.D.® propolis) in patients with symptoms of upper respiratory tract diseases (n = 58, from 18 to 77 years of age). Propolis was administered at a dose of 2–4 sprays (0.8–1.6 mL of propolis) three times per day (5 days). The remission of symptoms was observed in 83% of patients after three days of therapy. Previously, Di Pierro et al. [73] showed that a mixture of propolis-phytosome (Propolisina®) containing a 75 mg/sachet of pure propolis was effective in an open-label, retrospective, controlled clinical study involving patients with nonstreptococcal and viral pharyngitis caused by paramyxoviruses, rhinoviruses, adenoviruses. This product decreased the severity of symptoms such as sore throat, fever and pharyngeal erythema.

Additionally, Cohen et al. [74] drew attention to a herbal preparation containing propolis (50 mg/mL), Echinacea (50 mg/mL) and vitamin C (10 mg/mL) in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in order to assess its effectiveness in preventing upper respiratory tract infections in children (from 1 to 5 years of age). This preparation was administered to patients at doses of 5.0 mL and 7.5 mL twice daily for 12 weeks. Patients receiving the preparation experienced a 55% reduction in the number of illness episodes and a 62% reduction in the number of days with fever, as well as an overall decrease in the total number of days with symptomatic illness. According to Salatino et al. [10], the number of clinical studies has increased; however, most were carried out with the herpes simplex and influenza viruses. In fact, recent review articles are still describing old data on the antiviral activities of propolis. Table 2 contains summary of antiviral activity of propolis against viral respiratory diseases based on clinical studies.

Table 2.

Summary of antiviral activity of propolis against viral respiratory diseases based on clinical studies.

7. Conclusions

There are many mechanisms by which propolis exerts its antimicrobial effects, with more continuously being elucidated. Many articles outline a wide range of actions of propolis against microorganisms. Experimental studies (in vitro and in vivo) as well as clinical trials have shown that propolis extracts are an effective option in the prevention and treatment of respiratory tract diseases caused by viruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, influenza viruses, the parainfluenza virus and rhinoviruses. Propolis likewise shows anti-inflammatory activity, thus offering a potential mechanism to combat the cytokine storm observed during some SARS-CoV-2 infections. Despite recent advances in the field, the authors suggest that more research needs to be undertaken to establish the effects of combining propolis with conventional antiviral medications. Such a combination is promising because of the potential synergistic effects between propolis, its biologically active compounds and existing antiviral medications. Furthermore, propolis has been shown to be beneficial in the management of hyperglycemia and hypertension; thus, extracts can be used to lessen the burden imposed by comorbid diseases in patients with respiratory tract infections. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no systematic research being conducted on the activity of different types of propolis with respect to the treatment of respiratory tract diseases at the time of writing. Moreover, it is evident that despite the growing body of knowledge with respect to the mechanisms of action of propolis, there is a pronounced lack of clinical trials involving its use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.O. and T.M.K.; methodology, M.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.O.; writing—review and editing, M.O. and T.M.K.; visualization, M.O. and T.M.K.; supervision, M.O. and T.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Not applicable.

References

- Kuropatnicki, A.K.; Szliszka, E.; Krol, W. Historical aspects of propolis research in modern times. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 964149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojczyk, E.; Klama-Baryła, A.; Łabuś, W.; Wilemska-Kucharzewska, K.; Kucharzewski, M. Historical and modern research on propolis and its application in wound healing and other fields of medicine and contributions by Polish studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seçilmiş, Y.; Silici, S. Bee product efficacy in children with upper respiratory tract infections. Turk J. Pediatr. 2020, 62, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavacca, A.; Sangiovanni, E.; Racagni, G.; Dell'Agli, M. The antiviral and immunomodulatory activities of propolis: An update and future perspectives for respiratory diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 897–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, S.; Akyol, S. The consumption of propolis and royal jelly in preventing upper respiratory tract infections and as dietary supplementation in children. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulhendri, F.; Perera, C.O.; Tandean, S.; Abdulah, R.; Herman, H.; Christoper, A.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Putra, A.; Lesmana, R. The Potential use of propolis as a primary or an adjunctive therapy in respiratory tract-related diseases and disorders: A systematic scoping review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferkol, T.; Schraufnagel, D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11, 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, F.; Kodjamanova, P.; Chen, X.; Li, N.; Atanasov, P.; Bennetts, L.; Patterson, B.J.; Yektashenas, B.; Mesa-Frias, M.; Tronczynski, K.; et al. Economic burden of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. ClinicoEcon. Outcomes Res. 2022, 14, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripari, N.; Sartori, A.A.; Honorio, M.S.; Conte, F.L.; Tasca, K.I.; Santiago, K.B.; Sforcin, J.M. Propolis antiviral and immunomodulatory activity: A review and perspectives for COVID-19 treatment. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salatino, A. Perspectives for Uses of Propolis in Therapy against Infectious Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.F.; Wang, K.C.; Chiang, L.C.; Shieh, D.E.; Yen, M.H.; San Chang, J. Water extract of licorice had anti-viral activity against human respiratory syncytial virus in human respiratory tract cell lines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Yin, A.; Shan, J.; Wang, S.; Cai, B.; Di, L. Study on the rationality for antiviral activity of Flos Lonicerae Japonicae-Fructus Forsythiae herb couple preparations improved by chito-oligosaccharide via integral pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2017, 22, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Saddique, M.A.B.; Tahir, H.; Amjad, M.D.; Ahmad, A.; Masood, U.; Khan, D. A Short Review on Key Role of Plants and their Extracts in Boosting up Immune Response to Combat COVID-19. Infect. Disord. Drug. Targets 2022, 22, e270521193625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malekmohammad, K.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Mechanistic aspects of medicinal plants and secondary metabolites against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 3996–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidnia, M.; Sewell, R.D.E.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. An Update on Promising Agents against COVID-19: Secondary metabolites and mechanistic aspects. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2022, 28, 2415–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilokthornsakul, W.; Kosiyaporn, R.; Wuttipongwaragon, R.; Dilokthornsakul, P. Potential effects of propolis and honey in COVID-19 prevention and treatment: A systematic review of in silico and clinical studies. J. Integr. Med. 2022, 20, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Maleka, M.F.; Onyeaka, H.; Maleke, M.; Maolloum, A.; Godoy, L.; Meskini, M.; Rami, M.R.; Ahmadi, S.; et al. Propolis efficacy on SARS-COV viruses: A review on antimicrobial activities and molecular simulations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 58628–58647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, S.; Naghizadeh, A.; Karimi, M.; Zarei, A.; Mardi, R.; Kordafshari, G.; Esmaealzadeh, N.; Zargaran, A. COVID-19: General strategies for herbal therapies. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2022, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sberna, G.; Biagi, M.; Marafini, G.; Nardacci, R.; Biava, M.; Colavita, F.; Piselli, P.; Miraldi, E.; D’Offizi, G.; Capobianchi, M.R.; et al. In vitro evaluation of antiviral efficacy of a standardized hydroalcoholic extract of poplar type propolis against SARS-CoV-2. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13, 799546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelic, K.; Hitl, M.; Kladar, N. Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of SARS-CoV-2—Clinical Evidence. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, A.C.; Scorza, C.A.; de Almeida AC, G.; Fonseca, M.; Finsterer, J.; Fonseca, F.L.; Scorza, F.A. Antiviral activity of Brazilian green propolis extract against SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2) infection: Case report and review. Clinics 2021, 76, e2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güler, H.İ.; Ay Şal, F.; Can, Z.; Kara, Y.; Yildiz, O.; Beldüz, A.O.; Canakci, S.; Kolayli, S. Targeting CoV-2 spike RBD and ACE-2 interaction with flavonoids of Anatolian propolis by in silico and in vitro studies in terms of possible COVID-19 therapeutics. Turk J. Biol. 2021, 45, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harisna, A.H.; Nurdiansyah, R.; Syaifie, P.H.; Nugroho, D.W.; Saputro, K.E.; Prakoso, F.C.D.; Rochman, N.T.; Maulana, N.N.; Noviyanto, A.; Mardliyati, E.; et al. In silico investigation of potential inhibitors to main protease and spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 in propolis. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, W.G.; Brito, J.C.M.; da Cruz Nizer, W.S. Bee products as a source of promising therapeutic and chemoprophylaxis strategies against COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). Phyther. Res. 2020, 35, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat, H.; Mady, F.M.; Sarhan, H.A.; Rateb, H.S.; Alaaeldin, E. Optimization and evaluation of propolis liposomes as a promising therapeutic approach for COVID-19. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 592, 120028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, A.A.; Silveira, M.A.D.; Cóndor Capcha, J.M.; De Jong, D. Propolis and its potential against SARS-CoV-2 infection mechanisms and COVID-19 disease: Running title: Propolis against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 131, 110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachevski, D.; Damevska, K.; Simeonovski, V.; Dimova, M. Back to the basics: Propolis and COVID-19. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruta, H.; He, H. PAK1-blockers: Potential Therapeutics against COVID-19. Med. Drug Discov. 2020, 6, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulhendri, F.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Kowacz, M.; Ravalia, M.; Kripal, K.; Fearnley, J.; Perera, C.O. Antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic properties of propolis: A review. Foods 2021, 10, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, P.P.; Hudz, N.; Yezerska, O.; Horcinová-Sedlácková, V.; Shanaida, M.; Korytniuk, O.; Jasicka-Misiak, I. Chemical Variability and Pharmacological Potential of Propolis as a Source for the Development of New Pharmaceutical Products. Molecules 2022, 27, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozarowski, M.; Karpinski, T.M.; Alam, R.; Łochynska, M. Antifungal Properties of Chemically Defined Propolis from Various Geographical Regions. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybyłek, I.; Karpiński, T.M. Antibacterial Properties of Propolis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosri, N.; Abd El-Wahed, A.A.; Ghonaim, R.; Khattab, O.M.; Sabry, A.; Ibrahim, M.A.A.; Moustafa, M.F.; Guo, Z.; Zou, X.; Algethami, A.F.M.; et al. Anti-viral and immunomodulatory properties of propolis: Chemical diversity, pharmacological properties, preclinical and clinical applications, and in silico potential against SARS-CoV-2. Foods 2021, 10, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münstedt, K. Bee products and the treatment of blister-like lesions around the mouth, skin and genitalia caused by herpes viruses -A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 43, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kai, H.; Obuchi, M.; Yoshida, H.; Watanabe, W.; Tsutsumi, S.; Park, Y.K.; Matsuno, K.; Yasukawa, K.; Kurokawa, M. In vitro and in vivo anti-influenza virus activities of flavonoids and related compounds as components of Brazilian propolis (AF-08). J. Funct. Foods 2014, 8, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.J.; Shin, H.M.; Perumalsamy, H.; Wang, X.; Ahn, Y.J. Antiviral effects and possible mechanisms of action of constituents from Brazilian propolis and related compounds. J. Apic. Res. 2020, 59, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolonski, A.R.; Fonseca, M.S.; Machado, B.A.S.; Deegan, K.R.; Araújo, R.P.C.; Umsza-Guez, M.A.; Meyer, R.; Portela, R.W. Activity of antifungal drugs and Brazilian red and green propolis extracted with different methodologies against oral isolates of Candida spp. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stähli, A.; Schröter, H.; Bullitta, S.; Serralutzu, F.; Dore, A.; Nietzsche, S.; Milia, E.; Sculean, A.; Eick, S. In vitro activity of propolis on oral microorganisms and biofilms. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasote, D.; Bankova, V.; Viljoen, A.M. Propolis: Chemical diversity and challenges in quality control. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1887–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullkiflee, N.; Taha, H.; Usman, A. Propolis: Its Role and Efficacy in Human Health and Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Beltrán, N.P.; Galvéz-Ruíz, J.C.; Ikner, L.A.; Umsza-Guez, M.A.; de Paula Castro, T.L.; Gerba, C.P. In vitro antiviral effect of Mexican and Brazilian propolis and phenolic compounds against human coronavirus 229E. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.M.; Kunugi, H. Propolis, bee honey, and their components protect against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review of in silico, in vitro, and clinical studies. Molecules 2021, 26, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, S.; Sauter, D.; Wang, K.; Zhang, R.; Sun, B.; Karioti, A.; Bilia, A.R.; Efferth, T.; Schwarz, W. Kaempferol derivatives as antiviral drugs against the 3a channel protein of coronavirus. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Michaelis, M.; Hsu, H.K.; Tsai, C.C.; Yang, K.D.; Wu, Y.C.; Cinatl, J., Jr.; Doerr, H.W. Toona sinensis Roem tender leaf extract inhibits SARS coronavirus replication. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 120, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Li, Z.; Yuan, K.; Qu, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, H.; Luo, H.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, P.; et al. Small molecules blocking the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into host cells. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 11334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ting, Z.; Jiang, D.; Sheng, C.; Fan, Y.; Qi, J. Anti-enterovirus 71 effects of chrysin and its phosphate ester. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Sarkar, A.; Maulik, U. Molecular docking study of potential phytochemicals and their efects on the complex of SARS-CoV2 spike protein and human ACE2. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.A.D.; De Jong, D.; Berretta, A.A.; Galvão, E.B.D.S.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Cerqueira-Silva, T.; Amorim, T.C.; da Conceicao, L.F.M.R.; Gomes, M.M.D.; Teixeira, M.B.; et al. Efficacy of Brazilian green propolis (EPP-AF®) as an adjunct treatment for hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miryan, M.; Soleimani, D.; Dehghani, L.; Sohrabi, K.; Khorvash, F.; Bagherniya, M.; Sayedi, S.M.; Askari, G. The effect of propolis supplementation on clinical symptoms in patients with coronavirus (COVID-19): A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosari, M.; Noureddini, M.; Khamechi, S.P.; Najafi, A.; Ghaderi, A.; Sehat, M.; Banafshe, H.R. The effect of propolis plus Hyoscyamus niger L. methanolic extract on clinical symptoms in patients with acute respiratory syndrome suspected to COVID-19: A clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2021, 35, 4000–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investigation of Clinical Effectiveness of Propolis Extracts as Food Supplements in Patients with SARS-CoV-2(COVID-19). Identifier: NCT04916821. Available online: https://beta.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04916821?distance=50&cond=SARS-CoV-2&term=propolis&rank=1 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Zorlu, D. COVID-19 and anatolian propolis: A case report. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2021, 37, 1229–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, A.P.; Zhang, J.Y.; Li, J.Q.; Muhammad, A.; Abubakar, M.B. Herbal medications and natural products for patients with covid-19 and diabetes mellitus: Potentials and challenges. Phytomed Plus 2022, 2, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balica, G.; Vostinaru, O.; Stefanescu, C.; Mogosan, C.; Iaru, I.; Cristina, A.; Pop, C.E. Potential Role of Propolis in the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic Diseases. Plants 2021, 10, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayyal, M.T.; El-Ghazaly, M.A.; El-Khatib, A.S.; Hatem, A.M.; de Vries, P.J.; El-Shafei, S.; Khattab, M.M. A clinical pharmacological study of the potential beneficial effects of a propolis food product as an adjuvant in asthmatic patients. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 17, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, H.; Francisco, R.; Saraiva, A.; Francisco, S.; Carrascosa, C.; Raposo, A. The cardiovascular therapeutic potential of propolis—A comprehensive review. Biology 2021, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, J.M.; Zhao, C.Y.; Tarquinio, K.M.; Brown, S.P. Causes and consequences of COVID-19-associated bacterial infections. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 682571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourajam, S.; Kalantari, E.; Talebzadeh, H.; Mellali, H.; Sami, R.; Soltaninejad, F.; Amra, B.; Sajadi, M.; Alenaseri, M.; Kalantari, F.; et al. Secondary bacterial infection and clinical characteristics in patients with COVID-19 admitted to two intensive care units of an academic hospital in Iran during the first wave of the pandemic. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 784130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.N.; Akter, S.; Mishu, I.D.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.S.; Akhter, M.; Islam, I.; Hasan, M.M.; Rahaman, M.M.; Sultana, M.; et al. Microbial co-infections in COVID-19: Associated microbiota and underlying mechanisms of pathogenesis. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 156, 104941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, F.F.; Natzir, R.; Patellongi, I.; Santoso, A.; Hatta, M.; Junita, A.R.; Syukri, A.; Primaguna, M.R.; Dwiyanti, R.; Febrianti, A. In vivo and in vitro inhibition effect of propolis on Klebsiella pneumoniae: A review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 81, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhayawi, M.S. Propolis as a novel antibacterial agent. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 3079–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeki, T.M.; Hui, D.S.; Zambon, M.; Wentworth, D.E.; Monto, A.S. Influenza. Lancet 2022, 400, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Influenza (Seasonal). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Governa, P.; Cusi, M.G.; Borgonetti, V.; Sforcin, J.M.; Terrosi, C.; Baini, G.; Miraldi, E.; Biagi, M. Beyond the biological effect of a chemically characterized poplar propolis: Antibacterial and antiviral activity and comparison with flurbiprofen in cytokines release by LPS stimulated human mononuclear cells. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemura, T.; Urushisaki, T.; Fukuoka, M.; Hosokawa-Muto, J.; Hata, T.; Okuda, Y.; Hori, S.; Tazawa, S.; Araki, Y.; Kuwata, K. 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, a major constituent of Brazilian propolis, increases TRAIL expression and extends the lifetimes of mice infected with the Influenza A Virus. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 946867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urushisaki, T.; Takemura, T.; Tazawa, S.; Fukuoka, M.; Hosokawa-Muto, J.; Araki, Y.; Kuwata, K. Caffeoylquinic acids are major constituents with potent anti-influenza effects in brazilian green propolis water extract. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 2011, 254914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujumgiev, A.; Tsvetkova, I.; Serkedjieva, Y.; Bankova, V.; Christov, R.; Popov, S. Antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activity of propolis of different geographic origin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 64, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Hino, A.; Tsutsumi, A.; Park, Y.K.; Watanabe, W.; Kurokawa, M. Anti-influenza virus activity of propolis in vitro and its efficacy against influenza infection in mice. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2008, 19, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serkedjieva, J.; Manolova, N.; Bankova, V. Anti-influenza virus effect of some propolis constituents and their analogues (esters of substituted cinnamic acids). J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, L.; De Vecchi, E.; Nicola, L.; Gismondo, M.R. In vitro antimicrobial activity of a novel propolis formulation (Actichelated propolis). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Ren, J.; Li, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, G. Global burden of upper respiratory infections in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019. EClinicalMedicie 2021, 37, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, C.; Garzarella, E.U.; Bocchino, B.; D'Avino, M.; Caruso, G.; Buonomo, A.R.; Sacchi, R.; Galeotti, F.; Tenore, G.C.; Zaccaria, V.; et al. A standardized polyphenol mixture extracted from poplar-type propolis for remission of symptoms of uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection (URTI): A monocentric, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 80, 153368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, F.; Zanvit, A.; Colombo, M. Role of a proprietary propolis-based product on the wait-and-see approach in acute otitis media and in preventing evolution to tracheitis, bronchitis, or rhinosinusitis from nonstreptococcal pharyngitis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2016, 9, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, H.A.; Varsano, I.; Kahan, E.; Sarrell, E.M.; Uziel, Y. Effectiveness of an herbal preparation containing echinacea, propolis, and vitamin C in preventing respiratory tract infections in children: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).