Host–Guest Cocrystallization of Phenanthrene[2]arene Macrocycles Facilitating Structure Determination of Liquid Organic Molecules

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

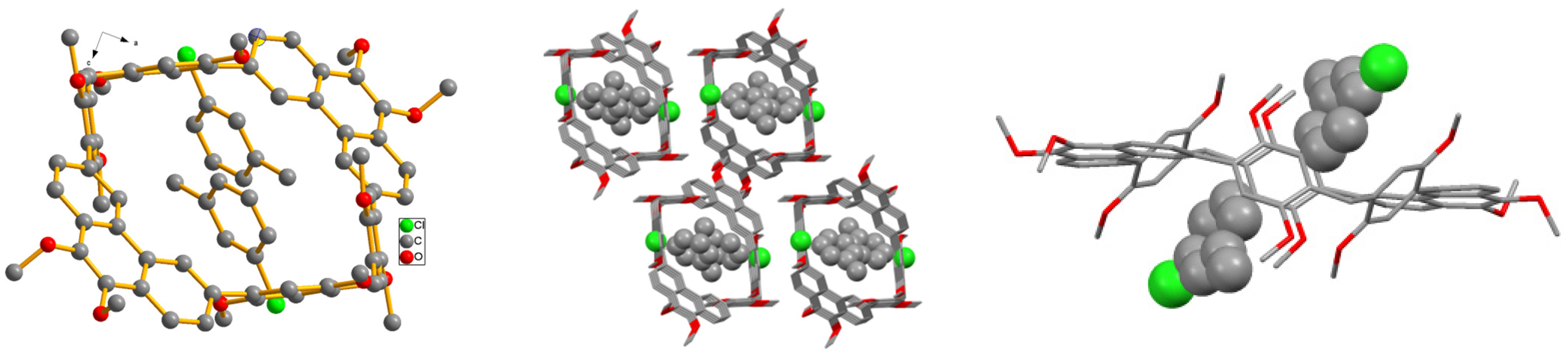

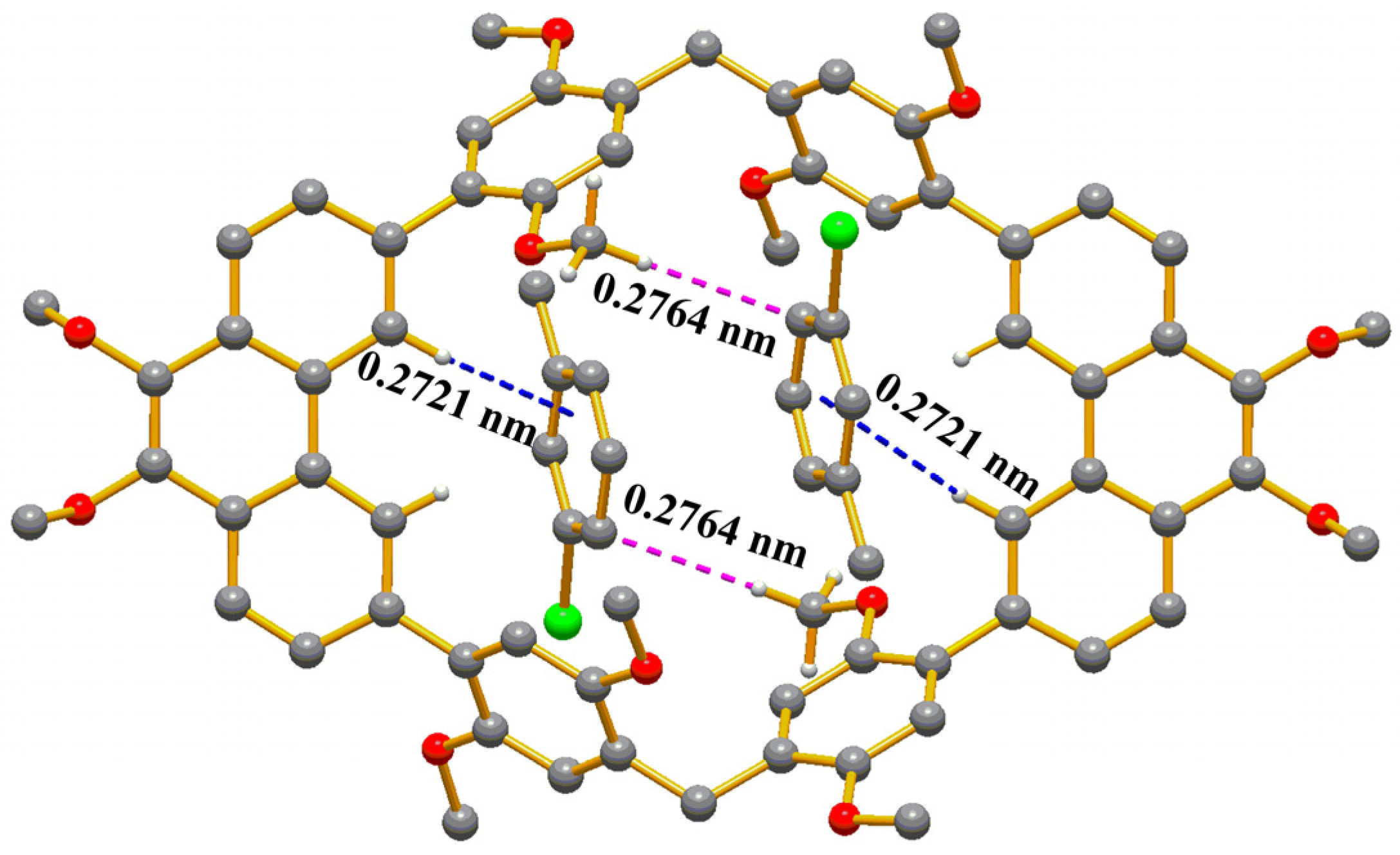

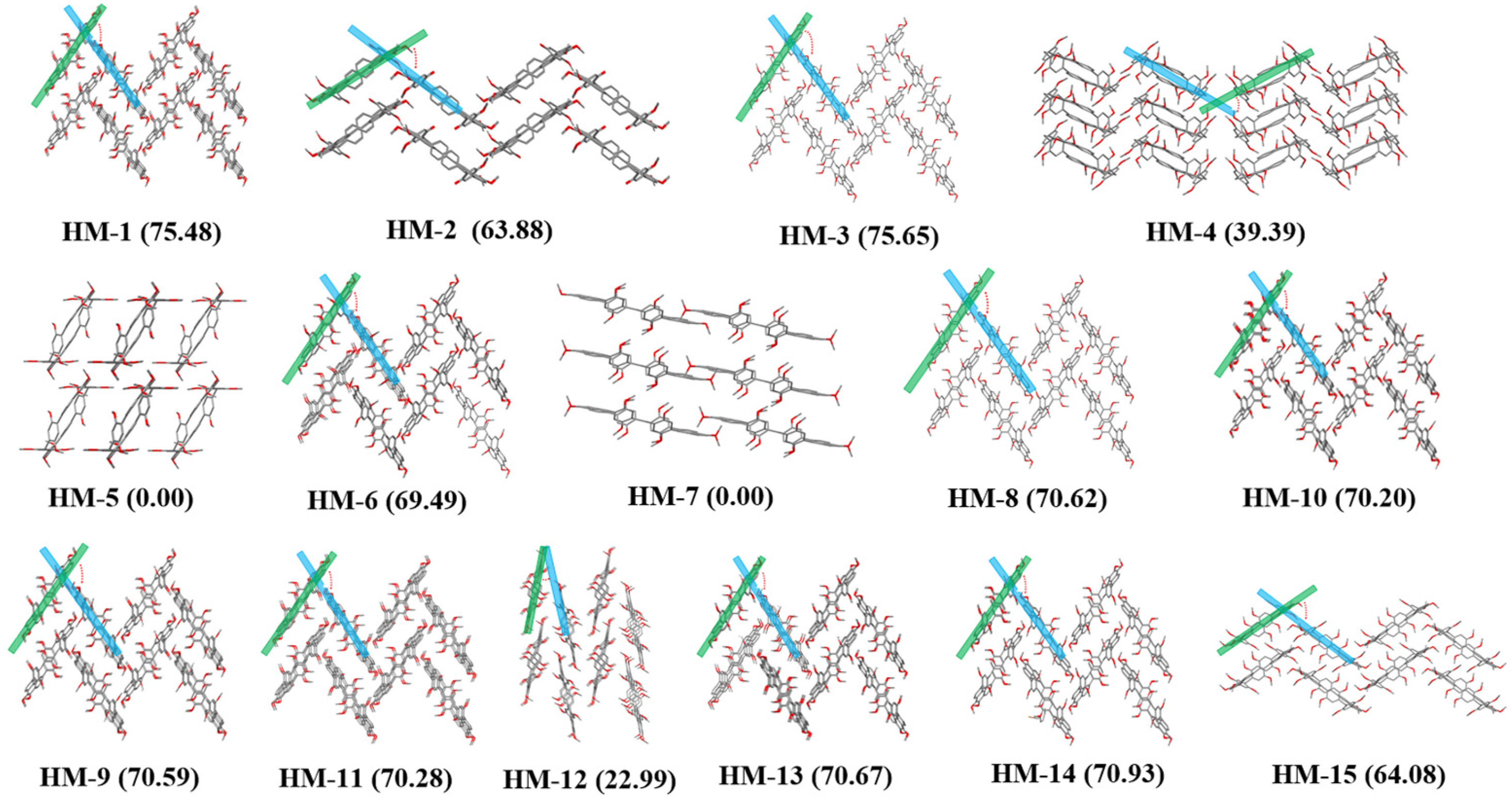

Description of Structures

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods for Cocrystallization

3.2. Crystal Structure Determination

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zigon, N.; Duplan, V.; Wada, N.; Fujita, M. Crystalline sponge method: X-ray structure analysis of small molecules by post orientation within porous crystals-principle and proof-of-concept studies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25204–25222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenal, A.D.; Ramadhar, T.R. Application of crystalline matrices for the structural determination of organic molecules. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metherall, J.P.; Carroll, R.C.; Coles, S.J.; Hall, M.J.; Probert, M.R. Advanced crystallisation methods for small organic molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 1995–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inokuma, Y.; Yoshioka, S.; Ariyoshi, J.; Arai, T.; Hitora, Y.; Takada, K.; Matsunaga, S.; Rissanen, K.; Fujita, M. X-ray analysis on the nanogram to microgram scale using porous complexes. Nature 2013, 495, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inokuma, Y.; Yoshioka, S.; Ariyoshi, J.; Arai, T.; Fujita, M. Preparation and guest-uptake protocol for a porous complex useful for ‘crystal-free’ crystallography. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka, S.; Inokuma, Y.; Hoshino, M.; Sato, T.; Fujita, M. Absolute structure determination of compounds with axial and planar chirality using the crystalline sponge method. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 3765–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigon, N.; Hoshino, M.; Yoshioka, S.; Inokuma, Y.; Fujita, M. Where is the Oxygen? Structural Analysis of α-Humulene Oxidation Products by the Crystalline Sponge Method. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9033–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inokuma, Y.; Kawano, M.; Fujita, M. Crystalline molecular flasks. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, G.A.; Maruyama, A.; Inokuma, Y.; Fujita, M.; Baran, P.S.; Blackmond, D.G. Radical C-H functionalization of heteroarenes under electrochemical control. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11868–11871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kapustin, E.A.; Yaghi, O.M. Coordinative alignment of molecules in chiral metal–organic frameworks. Science 2016, 353, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Burgi, H.B.; Kapustin, E.A.; Liu, Y.; Yaghi, O.M. Coordinative alignment in the pores of MOFs for the structural determination of N-, S-, and P-containing organic compounds including complex chiral molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18862–18869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, T.N.; Scheer, M. A novel crystalline template for the structural determination of flexible chain compounds of nanoscale length. Chem 2023, 9, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, E.; Escudero-Adan, E.C.; Bauza, A.; Ballester, P.; Frontera, A.; Rotger, C.; Costa, A. A crystalline sponge based on dispersive forces suitable for X-ray structure determination of included molecular guests. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 5466–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Di, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Wu, M.; Hong, M. An ultrastable p-p stacked porous organic molecular framework as a crystalline sponge for rapid molecular structure determination. CCS Chem. 2022, 4, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tang, S.; Yusov, A.; Rose, J.; Borrfors, A.N.; Hu, C.T.; Ward, M.D. Hydrogen-bonded frameworks for molecular structure determination. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenger, A.; Frey, W.; Richert, C. Tetrakis(dimethoxyphenyl)adamantane (TDA) and its inclusion complexes in the crystalline state: A versatile carrier for small molecules. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 8781–8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre, P.E.; Schwenger, A.; Frey, W.; Richert, C. High-loading crystals of tetraaryladamantanes and the uptake and release of aromatic hydrocarbons from the gas phase. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 9018–9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenger, A.; Frey, W.; Richert, C. Reagents with a crystalline coat. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13706–13709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupp, F.; He, S.; Frey, W.; Richert, C. A crystalline ready-to-use form of cyclopentadiene. Synlett 2018, 29, 1707–1710. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, F.; Frey, W.; Richer, C. Absolute configuration of small molecules by co-crystallization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15875–15879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, F.; Nowak, J.; Krupp, F.; Frey, W.; Richert, C. Co-crystallization of an organic solid and a tetraaryladamantane at room temperature. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, F. Structure and absolute configuration of liquid molecules based on adamantane derivative cocrystallization. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 6459–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.C.; Kariuki, B.M.; Hughes, C.E.; Logsdail, A.J.; Harris, K.D.M. Polymorphism in a multicomponent crystal system of trimesic acid and t-butylamine. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 5736–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldyn, M.R.; Larowska, D.; Bartoszak-Adamska, E. Novel rurine alkaloid cocrystals with trimesic and hemimellitic acids as coformers: Synthetic approach and supramolecular analysis. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Saha, B.K. Guest-induced isomerization of net and polymorphism in trimesic acid–arylamine complexes. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 2194–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, G.C.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X.F. Phenol derivatives as co-crystallized templates to modulate trimesic-acid-based hydrogen-bonded organic molecular frameworks. Crystals 2021, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceborska, M. Structural investigation of the b-cyclodextrin complexes with linalool and isopinocampheol-influence of monoterpenes cyclicity on the host–guest stoichiometry. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 651, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, K.; Zhou, Y.; Li, E.; Huang, F. Nonporous adaptive crystals of pillararenes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2064–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.G.; Zheng, J.; Wei, R.J.; Huang, Y.L.; Jiang, J.; Ning, G.H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, W.G.; Ye, W.C.; Li, D. Crystalline mate for structure elucidation of organic molecules. Chem 2024, 10, 924–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.M.; Li, H.; Xie, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.Y. Host-guest system of a phosphorylated macrocycle assisting structure determination of oily molecules in single-crystal form. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 11402–11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Cheng, L.; Ou, G.C.; Tang, L.L.; Ding, M.H. Pyromellitic diimide-extended pillar[6]arene: Synthesis, structure, and its complexation with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 3863–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Xiao, X.S.; Gong, S.F.; Yuan, L.; Tang, L.L. An electron-deficient supramolecular macrocyclic host for the selective separation of aromatics and cyclic aliphatics. Org. Chem. Front. 2022, 9, 4829–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.H.; Tang, L.L.; Liao, J.; Ou, G.C.; Zeng, F. High-yield synthesis of a novel water-soluble macrocycle for selective recognition of naphthalene. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 5, 1665–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS, Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Guest Molecules | Crystal System | Space Group | R1 | Angles # (°) | Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-chloro-3-methylbenzene (GM1) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0486 | 75.48 | (PTA)·(GM1)2 |

| 2 | 1-chloro-4-methylbenzene (GM2) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0567 | 63.88 | (PTA)·(GM2) |

| 3 | 1-bromo-3-methylbenzene (GM3) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0662 | 75.65 | (PTA)·(GM3)2 |

| 4 | (1-chloroethyl)benzene (GM4) | Monoclinic | C2/c | 0.0664 | 39.39 | (PTA)·(GM4)3 |

| 5 | (R)-(1-chloroethyl)benzene (GM5) | Triclinic | P-1 | 0.0686 | 0 | (PTA)·(GM5)2 |

| 6 | (S)-(1-chloroethyl)benzene (GM6) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.1054 | 69.49 | (PTA)·(GM6)2 |

| 7 | (1-bromoethyl)benzene (GM7) | Triclinic | P-1 | 0.0889 | 0 | (PTA)·(GM7)2 |

| 8 | 1-(bromomethyl)-3-methylbenzene (GM8) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.1206 | 70.62 | (PTA)·(GM8)2 |

| 9 | 1-(bromomethyl)-2-methylbenzene (GM9) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0702 | 70.59 | (PTA)·(GM9)2 |

| 10 | 1-(chloromethyl)-2-methylbenzene (GM10) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0727 | 70.20 | (PTA)·(GM10)2 |

| 11 | 1-(chloromethyl)-3-methylbenzene (GM11) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0729 | 70.28 | (PTA)·(GM11)2 |

| 12 | (2-chloroethyl)benzene (GM12) | Monoclinic | P21/c | 0.0872 | 22.99 | (PTA)·(GM12)2 |

| 13 | (chloromethyl)benzene (GM13) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.1015 | 70.67 | (PTA)·(GM13)2 |

| 14 | (bromomethyl)benzene (GM14) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0643 | 70.93 | (PTA)·(GM14)2 |

| 15 | pyridine (GM15) | Monoclinic | P21/n | 0.0720 | 64.08 | (PTA)·(GM15)2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ou, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, F. Host–Guest Cocrystallization of Phenanthrene[2]arene Macrocycles Facilitating Structure Determination of Liquid Organic Molecules. Molecules 2024, 29, 2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112523

Ou G, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Tan Y, Zhou Q, Zeng F. Host–Guest Cocrystallization of Phenanthrene[2]arene Macrocycles Facilitating Structure Determination of Liquid Organic Molecules. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112523

Chicago/Turabian StyleOu, Guangchuan, Yanfeng Zhang, Qiong Wang, Yingzhi Tan, Qiang Zhou, and Fei Zeng. 2024. "Host–Guest Cocrystallization of Phenanthrene[2]arene Macrocycles Facilitating Structure Determination of Liquid Organic Molecules" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112523

APA StyleOu, G., Zhang, Y., Wang, Q., Tan, Y., Zhou, Q., & Zeng, F. (2024). Host–Guest Cocrystallization of Phenanthrene[2]arene Macrocycles Facilitating Structure Determination of Liquid Organic Molecules. Molecules, 29(11), 2523. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112523