Abstract

III-nitrides are crucial materials for solar flow batteries due to their versatile properties. In contrast to the well-studied MOVPE reaction mechanism for AlN and GaN, few works report gas-phase mechanistic studies on the growth of InN. To better understand the reaction thermodynamics, this work revisited the gas-phase reactions involved in metal–organic vapor-phase epitaxy (abbreviated as MOVPE) growth of InN. Utilizing the M06-2X function in conjunction with Pople’s triple-ζ split-valence basis set with polarization functions, this work recharacterized all stationary points reported in previous literature and compared the differences between the structures and reaction energies. For the reaction pathways which do not include a transition state, rigorous constrained geometry optimizations were utilized to scan the PES connecting the reactants and products in adduct formation and XMIn (M, D, T) pyrolysis, confirming that there are no TSs in these pathways, which is in agreement with the previous findings. A comprehensive bonding analysis indicates that in TMIn:NH3, the In-N demonstrates strong coordinate bond characteristics, whereas in DMIn:NH3 and MMIn:NH3, the interactions between the Lewis acid and base fragments lean toward electrostatic attraction. Additionally, the NBO computations show that the H radical can facilitate the migration of electrons that are originally distributed between the In-C bonds in XMIn. Based on this finding, novel reaction pathways were also investigated. When the H radical approaches MMInNH2, MMIn:NH3 rather than MMInHNH2 will generate and this is followed by the elimination of CH4 via two parallel paths. Considering the abundance of H2 in the environment, this work also examines the reactions between H2 and XMIn. The Mulliken charge distributions indicated that intermolecular electron transfer mainly occurs between the In atom and N atom whiling forming (DMInNH2)2, whereas it predominately occurs between the In atom and the N atom intramolecularly when generating (DMInNH2)3.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, InN and its ternary alloy InGaN have garnered significant interest due to their low band gap energy (~0.6 ev), small effective mass of electrons, and high electron mobility. These properties position them as promising materials for various applications, including high-speed electronics, visible LED lights and solar flow batteries [1,2]. The primary technology employed for the preparation of InN and other III-nitride films is metal–organic vapor-phase epitaxy (abbreviated as MOVPE in further discussions) [3,4,5], which is favored for its scalability, high growth rate and excellent reproducibility.

MOVPE consists of two pivotal steps, and they are gas-phase reactions and surface reactions. Gas-phase reactions are crucial in determining the precursors for surface reactions, which, in turn, influence the growth rate and quality of films. Consequently, extensive research has been conducted to reveal the gas-phase reaction mechanisms of III-nitride films through the MOVPE process, particularly AlN and GaN [6,7,8,9,10]. And this paper concentrates on the gas-phase reaction mechanisms in InN growth specifically. It is recognized that there are two competing gas reaction paths during the growth of III-nitride films via MOVPE. The first pathway involves the pyrolysis of group-III precursors (typically TMX, X = Al, Ga and In) through a stepwise elimination of CH3 [6,8,10,11]. Utilizing a toluene carrier flow system, Jacko [12,13] studied the pyrolysis of TMX and concluded that the difficulty of pyrolysis follows the trend: TMX > MMX > DMX. Using a stagnation-point reactor, Hwang [14] investigated TMIn pyrolysis in an N2 atmosphere and found that TMIn pyrolysis occurs at a temperature range of 120–535 °C. However, these experiments could not accurately reflect the actual growth process due to the isolation of group-V precursor NH3. Mihopoulos [15] identified that mixing TMAl with NH3 can give rise to the instantaneous formation of a Lewis acid-base adduct, TMAl:NH3, which subsequently undergoes irreversible decomposition and releases CH4. This process is abbreviated as the “adduct path”, representing an alternative gas reaction pathway that is believed to initiate the formation of nanoparticles. Using in situ light scattering, Creighton [16] observed a layer of scattering by nanoparticles approximately 6 mm away from the substrate for both AlN, GaN and InN growth. In the case of AlN growth, the presence of CH4 was detected by FTIR measurements, whereas no CH4 was observed during the growth of GaN and InN. This discrepancy is attributed to the stronger Al-N bond compared to the Ga-N and In-N bonds. The stronger Al-N bond facilitates the formation of the amide DMAlNH2, accompanied by the elimination of CH4 through the irreversible decomposition of TMAl:NH3. In contrast, during the growth of GaN and InN, the adducts tend to undergo reversible dissociation back to TMGa or TMIn. Based on ab initio computations, Nakamura [17] concluded that the likelihood of CH4 elimination through the irreversible decomposition of adducts decreased down the periodic table and follows the trend: AlN > GaN ≈ InN. Agreeing with the theoretical investigations, experimental work [18] also suggests that the robust Al-N bond renders the irreversible decomposition of TMAl:NH3 as the predominant gas-phase reaction in AlN MOVPE growth. In addition to these two competing pathways, radicals may significantly influence how the gas-phase reaction progresses. In Creighton’s experimental study of GaN and InN growth [16], a switch in the carrier gas from H2 to N2 resulted in a notable decrease in scattering intensity from nanoparticles, while minima change was observed in AlN growth. This indicates that H radicals, which are produced from reactions involving H2, have a substantial impact on the growth of GaN and InN, whereas AlN is more inert to the radicals. Cavallotti [19] stated that both the pyrolysis path and the adduct path will be accelerated by the radicals, such as H produced by reactions between H2 and CH3 radicals.

The growth mechanisms of InN may differ significantly from those of AlN and GaN due to comparatively weaker bonds of In-N and In-C when contrasted with Al and Ga. However, despite the extensive studies on the growth mechanisms of AlN and GaN, very few gas-phase reaction mechanisms were targeted specifically on InN. Despite a systematic study on gas-phase reaction mechanisms in InN MOVPE growth from the thermodynamic and kinetic perspective performed using DFT calculations [18,20], the detailed bonding mechanisms of gas-phase reactions at the microscopic level are still unclear. To recalibrate the DFT baseline, all the gas-phase reactions of InN MOVPE proposed in previous research are revisited with a larger basis set in this study. The variations in energetics and kinetics were probed by comparing the benchmarking results reported herein with previous literature. Furthermore, all reactions reported herein will be investigated using the electrostatic potential (ESP), the natural bond orbital (NBO) and electron transfer to shed light on the detailed bonding mechanisms at the microscopic level.

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Revisit the Reaction Pathways Proposed in the Literature

Built on previous work [20], all electronic structures optimized at the M06-2X/6-31G(d,p) level of theory were recharacterized with the 6-311G(d,p). As illustrated in Tables S1 and S2, most bond lengths differ by less than 0.5%, and all bond angles are within a 0.85% deviation based on the stationary points in all proposed reaction pathways documented in the literature [20]. As illustrated in Table 1, the thermodynamic aspects of Ea and ∆H are consistent with the results reported in previous work that incorporate a polarized double-ζ split-valence basis, as the most exothermic reactions are XMIn pyrolysis reactions with H radicals involved, i.e., R5–R5b, while the most endothermic reactions are XMIn pyrolysis reactions (P4–P4b). When comparing these results, the extrapolated reaction enthalpies are always within 1.2 kJ/mol deviation. Similarly, the irreversible decomposition reactions of the adducts (A2 and A2a) always demand the largest energy input to overcome the energy barrier, with the evaluated Ea differing no more than 1.3 kJ/mol. These slight variations indicate that in conjunction with the M06-2X function, computations with a double-ζ basis set can provide reliable predictions on reaction energetics relative to a larger basis set and hence could be an option to better balance between computation cost and accuracy.

Table 1.

The activation energy (Ea, in kJ/mol) and enthalpy change (∆H, in kJ/mol) of all proposed reactions.

Adduct formation marks the beginning of the adduct path, which plays a crucial role in the competitive processes involved in the growth of III-nitride semiconductor thin films. Following the formation of the adduct, it may either dissociate back into TMIn and NH3 via reaction A1 or follow an irreversible decomposition reaction to form the DMInNH2 and CH4 via reaction A2. On the other hand, TMIn can also react with NH3 to form DMInNH2 through a bimolecular interaction (A3). As shown in Table 1, the Ea of reactions A2, A2a, and A2b are 202.74 kJ/mol, 119.58 kJ/mol and 86.25 kJ/mol, respectively. The Ea of A2 is ca. 83 kJ/mol and 116 kJ/mol higher compared to A2a and A2b. In addition, A2 and A2a are endothermic reactions, while A2b is an exothermic reaction. The heat released by A2b can supply the necessary energy needed to overcome the barrier and facilitate the chemical process, thus promoting the occurrence of the reaction. In this case, it is reasonable to conclude that reaction A2 presents a greater challenge to occur compared to A2a and A2b.

Another competitive reaction path is the pyrolysis of XMIn (where X = M, D, T). According to the ∆H of P4–P4b presented in Table 1, the likelihood of occurrence follows the trend P4a > P4b > P4. To further understand the bonding strength between In and C, the dissociation energy (abbreviated as BDE in following discussion) of TMIn, DMIn, and MMIn was determined via Equation (2) in Section 3 and the magnitude of these three are 304.63 kJ/mol, 128.02 kJ/mol, and 238.08 kJ/mol, respectively, indicating the required energy to dissociate the In-N bond follows the trend TMIn > MMIn > DMIn. This trend aligns with the findings in previous experimental research reported by Jacko [13]. Interestingly, the In-C bond lengths are 2.15 Å for TMIn, 2.19 Å for DMIn, and 2.23 Å for MMIn, which appears to contradict the trend observed in BDE analyses. This discrepancy suggests that there might be underlying mechanisms influencing this phenomenon. To further elucidate the distinct covalent bonding characteristics in these three molecules, an NBO analysis was conducted, and the results will be illustrated in Section 2.2.1.

A previous DFT computational study indicated that, in addition to direct pyrolysis, XMIn can also react with H radicals and proceed with stepwise CH4 eliminations. These reactions are denoted as R5–R5b listed in Table 1. When the environment is free of H radicals, the pyrolysis reactions (P4–P4b) have positive ΔGs, suggesting that these are non-spontaneous processes. In contrast, with a negative ΔG for pyrolysis reactions involving H radicals, the processes are spontaneous. Obviously, H radicals play a role in promotion of XMIn pyrolysis. From the ∆H listed in Table 1, reactions P4–P4b are endothermic; however, with the aid of H radicals, pyrolysis reactions R5–R5b are exothermic provided they overcome the Ea. The detailed bonding mechanism analysis of H radicals with XMIn is conducted in Section 2.2.2. Due to the high reactivity, H radicals can also react with amide and lead to CH4 elimination (R7–R9). In reaction R8, it is predicted that the H radical will interact with the In atom to yield MMInHNH2, given that both the In atom and the H radical have one unpaired electron. However, upon bringing the H radical near the N atom in MMInNH2, the unconstrained geometry optimization confirmed the minimum was the adduct, MMIn:NH3 rather than MMInHNH2. Denoted as R8a, the transformation from MMIn:NH3 to MMInHNH2 has a electronic energy difference ∆E of 6.13 kJ/mol, indicating that the product is more likely to be kept in the form of MMIn:NH3 while the interactions occur between the H radical and MMInNH2.

MMInNH2 + H→MMIn:NH3

MMIn:NH3→MMInHNH2

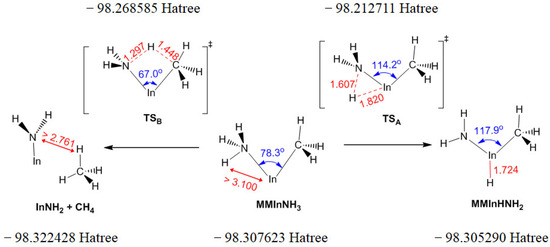

Based on the two isomeric minima characterized above, a TS was characterized using the QST2 method and verified MMIn:NH3 as the reactant and MMInHNH2 as the product. According to the above discussion, there are two parallel paths to eliminate CH4 from MMIn:NH3, one is reaction A2b listed in Table 1 (also the left path in Figure 1) and the other is the conversion of MMIn:NH3 to MMInHNH2 with a Ea of 229.97 kJ/mol (denoted as (R8b)) followed by the reaction R9 with the elimination of CH4 and the above process is denoted as the “H-shift path” (the right path in Figure 1). These two parallel paths and corresponding molecular structures are also illustrated in Figure 1. Further investigations into the chemical bonding of this process will be revealed with ESP and NBO in Section 2.2.2. The left pathway involves only one TS (TSB in Figure 1), whereas the path on the right needs to cross over two TSs (the TSA in Figure 1 and the TS in reaction R9); therefore, the Ea of the left path (86.25 kJ/mol) is lower than that of the right path (229.97 kJ/mol and 93.62 kJ/mol) and the left path may have a higher priority. When searching for TSA, the energy of the product InNH2 and CH4 optimized as a pair is ca. 9 kJ/mol lower than the summed energy when they are optimized in isolation.

Figure 1.

Two parallel paths with the elimination of CH4 from MMIn:NH3 and corresponding molecular structures.

Because CH3 radicals that are produced from XMIn pyrolysis can also react with the H2 carrier gas in group III-nitride MOVPE and generate H radicals, the reaction pathways could be altered via either the pyrolysis path (R5–R5b) or the adduct path (R7, R8a, R8b and R9). However, as the H radicals can also merge into H2, along with the H2 brought in by the substantial flow rate of the carrier gas in the reaction chamber, a set of novel reaction pathways H12–H14 (H2-invovled paths in the following discussion), as listed in Table 2, will be further discussed in Section 2.2.3.

Table 2.

The activation energy (Ea, in kJ/mol) and enthalpy change (∆H, in kJ/mol) of the H2-involved reactions.

2.2. NBO and ESP Analysis

2.2.1. Two Typical Competitive Routes in the InN MOVPE Process

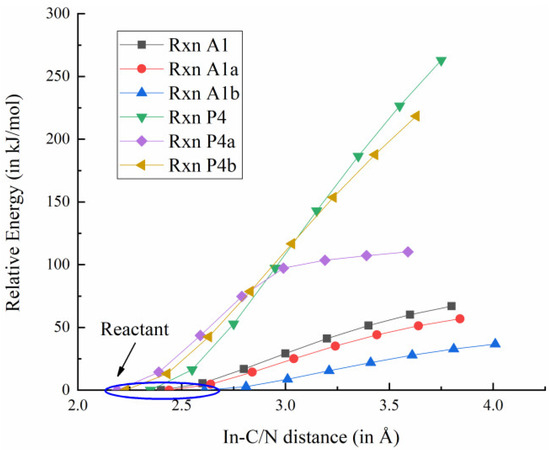

The adduct path represents a crucial competitive mechanism in the MOVPE process of III-nitrides, as the interaction between TMIn and NH3 can trigger a cascade of reactions that ultimately generate nanoparticles. Other than TMIn:NH3, similar reactions can occur with DMIn and MMIn [20], which are denoted as reactions A1, A1a and A1b in Table 1. It is anticipated that the rapid formation of the TMIn:NH3 adduct can process upon the collision of TMIn with NH3 without involving a TS [18]. To verify this interpretation and probe surface between the reactants and products in reactions A1, A1a and A1b, constrained geometry optimizations were employed to simulate the In-N bond formation and obtain reliable electronic energy. Take reaction A1 as an example—the In in TMIn and the N in NH3 were constrained as 3.8 Å apart, while the rest of the geometry parameters were relaxed through geometry optimization. This procedure was repeated to decrease the In-N distance from 3.6 Å to 2.4 Å, with a step size decrement of 0.2 Å. As illustrated in Figure 2, the monotonic change in electronic energy indicates that the rapid addition between a Lewis acid and base pair always occurs in one concerted step, which is consistent with previous research results [18].

Figure 2.

The relaxed scan for adduct formation (A1–A1b) and pyrolysis reaction (P4–P4b). [Annotation 1] The PES was explored by constrained geometry optimization, and connects the dissociated In(CH3)x−1 and CH3 or In(CH3)x and NH3. [Annotation 2] Relative Energy refers to the electron energy difference between the scan points and the 1st scan point (i.e., reactants).

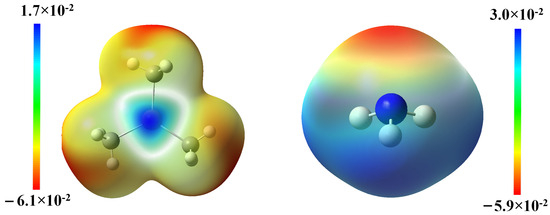

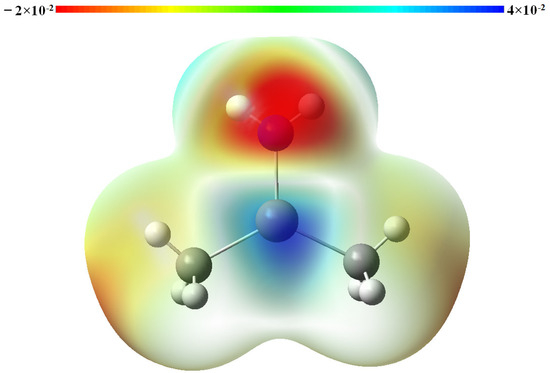

To gain insight into the electronic distributions among the pivotal structures in reaction A1, the ESP of the two reactants was mapped and illustrated in Figure 3. The results confirm that the electron-proficient N atom in NH3 might initiate a nucleophilic attack to the electron-deficient In center in TMIn and facilitate the formation of the dative In-N bond in TMIn:NH3.The summarized NBO analysis demonstrated in Table 3 indicates that the In-N bond consists of 5% electronic character from In and 95% from N. This finding further substantiates the notion that the non-bonding electron pair from N could migrate into the vacant valence orbitals of In, thereby facilitating the formation of a coordinate bond.

Figure 3.

The ESP map of TMIn and NH3.

Table 3.

NBO charges on TMIn:NH3 at M06-2X/6-311G(d,p) level of DFT theory.

The absences of TSs in reactions A1, A1a and A1b suggest that these reactions might proceed with similar mechanisms. To further substantiate this hypothesis, NBO analyses were conducted to probe the more detailed electron transfers in reactions A1a and A1b and the summarized results are illustrated in Tables S3 and S4. NBO analysis indicated that no bond was formed between In and N atoms in both DMIn:NH3 and MMIn:NH3, which is quite different from that of TMIn:NH3. From the perspective of In-N bond length, the In-N bond in DMIn:NH3 (2.44 Å) and especially in MMIn:NH3 (2.61 Å) differs distinctly from TMIn:NH3 (2.40 Å). Thus, qualitatively, the bonding mechanism of these adducts may be essentially different. To further verify the interactions between MMIn/DMIn and NH3, we extrapolated the interaction energy (abbreviated as Eint in following discussion) between the XMIn (X = M, D, T) and NH3 in TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, and MMIn:NH3 via Equation (3) in Section 3. The results suggest that TMIn exhibits the highest Eint with NH3, and it is ca. 20 and ca. 46 kJ/mol higher compared with DMIn and MMIn. Based on the Eint, the BDE values of them are also computed to further verify the bond strength between In and N in TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, and MMIn:NH3. The BDE values of TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, and MMIn:NH3 are 92.76 kJ/mol, 80.02 kJ/mol, and 54.05 kJ/mol, respectively. Additionally, the BDE values of the In-N bond for DMInNH2 and MMIn(NH2)2 are determined to be 381.61 kJ/mol and 370.57 kJ/mol, respectively, at the same computational level. These results are much larger than that for TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, and MMIn:NH3.

In addition, the Mayer bond order between In and N was verified via Multiwfn [21] in five pivotal structures, XMIn(NH2)Y (where X = M, D, T and Y = 1 or 2). Listed with BDE values in Table 4, the Mayer bond orders of the In-N bond are 0.205, 0.198, 0.142, 0.91, and 0.85 in TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, MMIn:NH3, DMInNH2, and MMIn(NH2)2, respectively. From the perspective of the NBO and Mayer bond order results, the In-N bond in DMInNH2, MMIn(NH2)2 is a single bond, while in TMIn:NH3, it is a single coordinate bond. Since NBO shows no bond between In and N for DMIn:NH3, MMIn:NH3 and the In-N bond orders of these two are lower than in TMIn:NH3; thus, we suspect that the interaction between In and N in DMIn:NH3 and MMIn:NH3 results from electrostatic attraction.

Table 4.

The BDE values of the In-N bond (in kJ/mol), Mayer bond order and the Mulliken charge transfer (NB→A, in Atomic Units) between In and N in XMIn:NH3 and XMIn(NH2)Y where X = M, D, T and Y = 1, 2.

To further probe the charge distributions between In and N in XMIn:NH3 (where X = M, D and T), the Mulliken charge transfer was assessed. For a Lewis adduct AB which consists of the acid (A) and base (B), the charge transferred from segment B to segment A (NB→A) is determined using Equation (1), where NB,P and NB,R are the Mulliken charge of segment B in the product and reactant, respectively.

NB→A = NB,P − NB,R

As a result, the NB→A in TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, and MMIn:NH3 is 0.126 a.u., 0.122 a.u., and 0.082 a.u., respectively, whereas the corresponding magnitudes in DMIn/MMInNH2 and DMInNH2/MMIn(NH2)2 are 0.427 a.u. and 0.447 a.u. This aligns with the weaker In-N bond strength probed in TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, and MMIn:NH3 and the stronger bond lengths in DMInNH2 and MMIn(NH2)2.

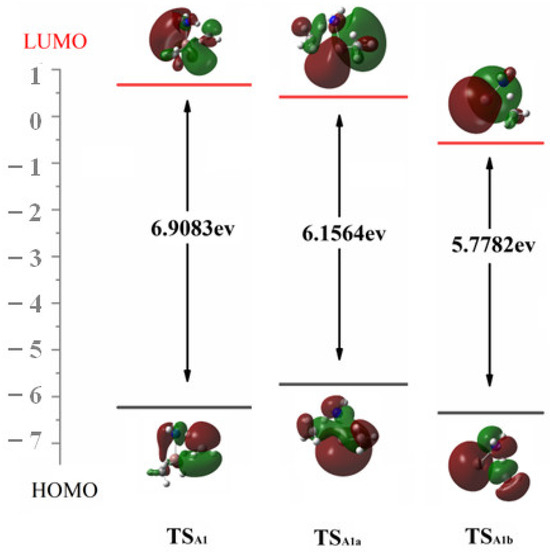

At the M06-2X/6-311G(d,p) level of theory, the HOMO–LUMO gaps for TSA1, TSA1a and TSA1b are 6.91 eV, 6.16 eV and 5.78 eV, respectively. Although conventional DFT functions are relatively inaccurate in predicting HOMO–LUMO gaps [22], we are only concerned with the HOMO–LUMO values of different TSs obtained at the same theoretical level. This monotonic decreasing trend lines up with the Ea of the reactions. Additionally, the HOMO and LUMO of these three TSs provide valuable insights for the simultaneous NH bond cleavage. As depicted in Figure 4, during the CH bond formation in reaction A1, the HOMO suggests that the active electrons are localized between N and H, as well as the C and H. This allows them to diffuse to the p-like orbitals on leaving CH3 and facilitate CH4 formation. Meanwhile, the unpaired single electron in LUMO back shifts to the electron-deficient In center and hence stabilize the In-N bond.

Figure 4.

The HOMO and LUMO and the associated Egap of TS in reactions A1, A1a and A1b.

Previous work indicates that upon being injected into the reaction chamber, XMIn (X = M, D, T) undergoes pyrolysis under high-temperature excitation and with stepwise elimination of CH3. These reactions are denoted as the pyrolysis path and illustrated in Table 1 (P4–P4b) [18]. Although no TS was reported in III-nitride film growth among these reactions [18,23], in this study, the PES between the predicted reactants and products was once again investigated through constrained geometry optimizations. To probe the energy change, the distance between the In and the C in TMIn was constrained at 3.75 Å, while the rest of the proposed structure was allowed to be optimized. Similar to the scans introduced above, settings were established and repeated with a 0.2 Å decrement in the step size to gradually decrease the In-C distance from 3.55 Å to 2.15 Å to mimic the pyrolysis process. As illustrated in Figure 2, no TS could be identified along the reaction coordinates. Utilizing the same method, comparable findings were obtained for pyrolysis processes P4a and P4b.

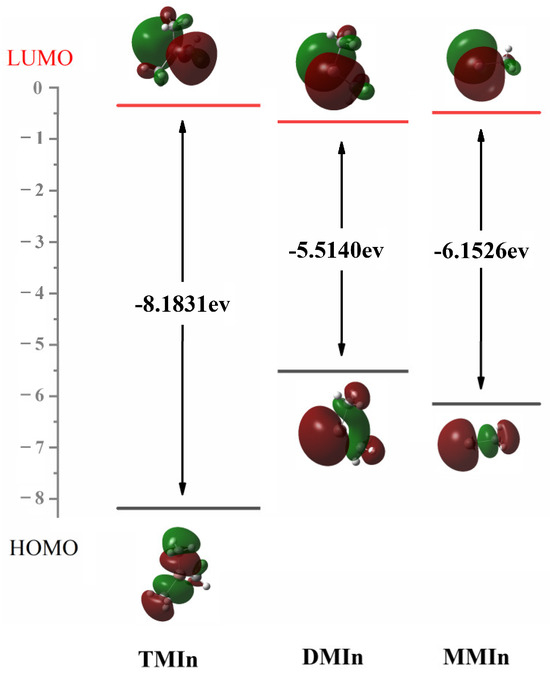

Also playing a critical role in the determination of the precursors for the subsequent surface reactions, XMIn pyrolysis serves as a significant alternative to the adduct route. As Section 2.1 concluded that the BDE trend contradicts the In-C bond length results, further NBO analysis (Table S5) was conducted on the associated three molecules to study the unique bonding in XMIn. The results indicated that the In atom of TMIn is bonded singly to three C atoms of CH3, resulting in a singlet ground state of TMIn. Similarly, the In atom in MMIn is bonded singly to a methyl group, so it also remains as a singlet with two electrons paired up. In contrast, in DMIn, the In atom only has one electron remaining after forming two In-C bonds with two methyl groups. This allows a DMIn doublet state. This pairing of spins leads to the significantly increased stability of singlet MMIn compared to DMIn. The FMOs for these three molecules were computed to further study the reactivity of the target molecules, and the HOMO–LUMO gaps are depicted in Figure 5. The largest HOMO–LUMO gap is observed in TMIn, followed by MMIn, while DMIn exhibits the smallest gap. Consequently, the HOMO–LUMO gap is positively correlated with the corresponding pyrolysis reaction difficulty.

Figure 5.

The HOMO and LUMO and the Egap (in eV) of TMIn, DMIn and MMIn.

2.2.2. The H Radical-Involved Path

The synthesis of group III-nitride thin films via MOVPE is often complicated by the abundant radicals in the environment due to the multiple side reactions that they can initiate. Among these radicals, the H radicals can be derived from two major paths: either the homolytic H2 cleavage at high temperature, or the reaction between H2 and CH3 radicals which are released by the group-III precursors [19]. So, how exactly do H radicals boost XMIn pyrolysis? To address this question, all associated pathways predicted herein were thoroughly investigated. Since the high reactivity of the H radical is due to its unpaired electron, when the H radical moves close to XMIn, the electrons originally distribute between In and C will transfer to the H radical, resulting in a decrease in the strength of the In-C bond, which makes XMIn easier to pyrolyze.

The dimensionless free energy barriers reported in previous studies indicates that the ΔG*/RT for the pyrolysis reactions with H radicals is 39.09, 29.23 and 22.75 for TMIn, MMIn and DMIn, respectively [20]. Because the consistent trend of T > M > D (referring to the methyl groups in each compound) was also observed in reactions P4–P4b, additional investigations were conducted to confirm the role of the unpaired electron and how it can affect the reactivity of XMIn in each reaction. As illustrated in Figure S1, the H radicals are pulled close to the In atom of DMIn due to the unpaired lone electron in both. However, for TMIn and MMIn, the interaction between the H radicals and the In atoms is blocked by the methyl groups. The Mayer bond order results also show that the bond order between the H radical and the In atom of DMIn is 0.625, and 0 for both TMIn and MMIn. Based on the above analysis, more electrons shifted between DMIn and the H radical, which led to DMIn being more reactive with the H radical than TMIn and MMIn. Moreover, because the steric hindrance at the In center in TMIn is significantly larger than MMIn, the pyrolysis reaction with H radicals is more likely to occur on MMIn than on TMIn.

The occupancy of the bonds in these three TSs also provides invaluable evidence to explain why three pyrolysis reactions demand different activation energies. As listed in Table S6, the occupancy between the C atom of leaving CH3 in DMIn and the H radical is notably close to 2. As a significant charge transfer would occur, the electrons are shifted away from In-C when the H radical attacks the methyl group. In contrast, the corresponding occupancy between the C atom of the leaving CH3 in MMIn and TMIn are 0.957 and 0.910, respectively. This suggests that DMIn exhibits a greater tendency to undergo pyrolysis than TMIn and MMIn.

In addition to participating in the pyrolysis reaction of XMIn, the H radical can react with the amides DMInNH2 (R7) and MMInNH2 (R8). Rather than combining with the amino group to produce NH3, the H radical attacks CH3 and forms CH4 when reacting with DMInNH2, which may be caused by the weaker In-C bond compared to the In-N bond. Computations indicate that the In-N bond is stronger than In-C in DMInNH2 as the former has a BDE of 310.24 kJ/mol while the latter has a magnitude of 381.61. Additionally, the Mayer bond order analysis completed by Multiwfn [21] indicates that In-C has a bond order of 0.84, an In-N has a bond order of 0.91. Meanwhile, the In-C bond length (2.14 Å) is longer compared to the In-N bond length (1.98 Å). In this case, the speculated statement can be verified with a comprehensive analysis from various aspects.

Previous investigations indicate that the H radical is expected to react with the amide MMInNH2 through reaction R8, resulting in the formation of the intermediate MMInHNH2, followed by an elimination reaction and release of CH4 (R9) [20]. However, the lower electronic energy reported in Section 2.1 suggests that MMIn:NH3 could be formed prior to MMInHNH2. As illustrated in Figure S2, the H radical is more likely to interact with the electron-proficient N in MMInNH2 (rather than the In atom), leading to the production of MMIn:NH3 finally. Thus, this justifies our speculation. After overcoming the energy barrier, MMIn:NH3 may convert to MMInHNH2, from the Mulliken charge distribution of MMIn:NH3, TSA in Figure 1 and MMInHNH2, electron transfer mainly from CH3 and In to NH3. One part of these electrons participated in the formation of the In-N bond in MMInHNH2. Comparing the NBO charges of the atoms in MMIn:NH3 (Table S4) and MMInHNH2 (Table S7) confirms the absence of the In-N bond in MMIn:NH3 and verifies the existence of a single In-N bond in MMInHNH2. The other part of the electrons transferred to the H atom, which is originally derived from the H radical, leading to the cleavage of the N-H bond in MMIn:NH3.

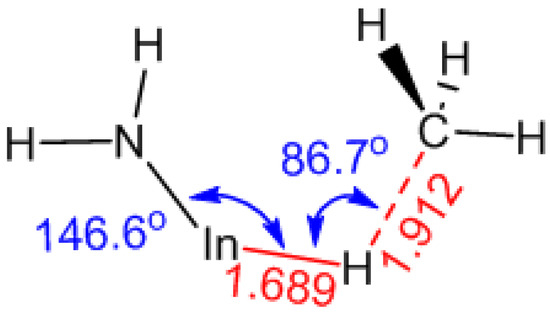

Following the formation of MMInHNH2, the subsequent elimination of CH4 through an intramolecular reaction R9 will take place after supposing a TS as depicted in Figure 6. In this process, the In-C will be cleaved first to allow the H atom to shift to a bridging position. Then, once the high-energy complex overcomes the energy barrier of 93.62 kJ/mol, the H atom will be shifted to the methyl group, leading to the generation of CH4. As illustrated in Figure S3, the Mulliken charges of the In atom, the H atom from the H radical and the C atom in the reactant, MMInHNH2, are 0.978, −0.213, −0.839, respectively. In contrast, in the characterized TS, these values shift to 0.693, 0.060, and −0.816, respectively, suggesting that predominant charge transfer occurs from H to In.

Figure 6.

The critical bond lengths and atom distances (in Å) along with bond angles (in o) in the fully optimized TS of R9.

2.2.3. The H2 Radical-Involved Path

As outlined in Section 2.1, the interaction between the H radicals results in a considerable presence of H2 in the reaction environment. H2 is capable of reacting with XMIn (X = M, D, T) via H12–H14, thereby significantly affecting the reaction pathways. As illustrated in Figure S4, the H atom in H2 can be attracted by electron-proficient C in XMIn (X = M, D, T) and through the TSs depicted in Figure S5, H-H and In-C bond cleavage will facilitate CH4 elimination. Figure S6 compares the Mulliken charges distributed in XMIn and the associated TSs in reaction H12–H14. It is observed that when H2 approaches the CH3 group in XMIn, the charge transfer mainly occurs between the H in H2 during the H-H cleavage.

To elucidate the differences in Ea, electron transfer was studied through Mulliken charge analysis for reactions H12–H14. Take H12 for example—excluding the leaving CH3 group, the total charges of the rest of the reactant and product are 0.359 a.u. and 0.219 a.u., and the sum of the charges transferred during the cleavage of In-C cleavage is 0.14 a.u. Utilizing the same method, the total charges transferred observed in H13 and H14 are 0.135 a.u. and 0.155 a.u. The trend of charge transfer follows the Ea among these three H2-invovled reactions and also follows the trend:H14 > H12 > H13, suggesting that the In-C bond in XMIn is more susceptible to cleavage and hence required a lower energy input to overcome the Ea.

2.2.4. The Amide Oligomerization Path

Nanoparticle deposition, often known as the “an unavoidable path”, presents a considerable challenge in the MOVPE growth of group III-nitrides. While numerous studies [16,18,19,23] have reported the nanoparticle compositions and elucidated their reaction thermodynamics and kinetics through both experimental and theoretical approaches, to the best of our knowledge, none have provided a comprehensive microscopic analysis of the formation and cleavage of chemical bonds in the predicted mechanisms. It is believed that nanoparticles begin to form when polymerizing the amide DMXNH2 (X = Al, Ga, In) [16,18,19,23]. Specifically, the amides first form cyclic dimers and trimers, which subsequently grow and increase in size via vapor-phase deposition. The reactions O10 and O11, as detailed in Table 1, correspond to the dimerization and trimerization of DMInNH2, respectively.

The ESP diagram of DMInNH2 (depicted in Figure 7) demonstrates that the electron-deficient In will interact with an electron-proficient N atom when two DMInNH2 molecules approach each other. This strong electrostatic interaction can initiate a nucleophilic attack: the N atom of one DMInNH2 molecule is prone to attacking the In atom in the neighboring DMInNH2 molecule, resulting in the formation of a tetragonal cyclic dimer. The Mulliken charge distribution of the monomer and the dimer (DMInNH2)2, as shown in Table 5, reveals that the In and N in DMInNH2 carries a charge of 1.128 a.u. and −0.913 a.u., respectively. In contrast, their Mulliken charges alter to 1.224 a.u. and −1.010 a.u., respectively, after the formation of (DMInNH2)2. Conversely, the Mulliken charge of C in DMInNH2 and (DMInNH2)2 remained nearly unchanged before and after the dimerization. Thus, during this process, electron transfer mainly occurs between an In atom in one DMInNH2 monomer and an N atom in another neighboring monomer. As demonstrated in Table 5, the charge distribution of the atoms in (DMInNH2)2 closely resembles that of the corresponding atoms in (DMInNH2)3. Thus, when DMInNH2 reacts with (DMInNH2)2 to generate (DMInNH2)3, the electrons mainly transfer from the In atom to the N atom intramolecularly in DMInNH2. The detailed NBO analyses on DMInNH2, (DMInNH2)2 and (DMInNH2)3 are listed in Table S8.

Figure 7.

The ESP map of DMInNH2.

Table 5.

Mulliken charge distribution of DMInNH2, (DMInNH2)2 and (DMInNH2)3.

3. Computation and Methodology

All proposed structures in this study were fully characterized utilizing the density function theory (DFT) method [24] via the Gaussian 09 program package [25]. All stationary points reported herein were fully optimized using M06-2X functions [26] in conjunction with Pople’s triple-ζ split-valence basis set with polarization functions [27]. Additionally, to better describe the In atoms involved in our predicted reaction pathway, the LAN2DZ [28] basis set was applied with the effect core potential (ECP) [29] to replace the inner 46 electrons. This level of theory will be denoted as M06-2X/6-311G(d,p) and is applied for the majority of the QM computations discussed herein unless otherwise specified. The vibrational frequencies of each stationary point were computed at the same level of theory to verify its nature as either a minimum (min, ni = 0) or a saddle point (TS, ni = 1) on the Born–Oppenheimer potential energy surface (PES). Additionally, the TSs were verified by intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) [30] scans to confirm that they connect two local minima along the vibrational mode that corresponds to the only imaginary frequency.

To better calibrate the DFT baseline, we selected the most representative reaction (A1, the addition between TMIn and NH3 to generate the TMIn:NH3 adduct) among all the tested chemical processes and conducted additional quantum mechanical computations. Utilizing different methods, the reaction enthalpy change (∆H, in kJ/mol) was evaluated and compared with the value we reported in this paper (at the M06-2X/6-311G(d,p) level of theory). The additional computations include using ab initio methods such as the second-order Møller–Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) [31], and coupled-cluster methods where the cluster operator contains all single and double substitutions (CCSD) [32,33,34,35] along with our selected Pople’s basis set. To examine the role of dispersion functions in the selected DFT function (M06-2X), we also calculated the reaction enthalpy using the M06 function [25]. Furthermore, the ∆H of A1 was also determined using the popular Becke 3-parameter Lee–Yang–Parr hybrid (B3LYP) [36] function. These additional computational results are reported in Table S9. Our results indicated that without the additional correlation correction, the ∆H of reaction A1 is 3.98 kJ/mol higher than the value we reported in Table 1, presenting a 4.59% deviation. Compared with the popular B3LYP function, which has a large ∆H of −71.19 kJ/mol (with 17.78% deviation), the differences between the results obtained using the M06 and M06-2X results are less prominent. In contrast, the smallest deviation is observed when comparing the results obtained using the ab initio MP2 methods and our selected M06-2X function with a Dev∆H of 2.95 kJ/mol (with 3.41% deviation). This suggests that M06-2X has the potential to provide quick yet reliable predictions when utilized with Pople’s split-valence basis set. Interestingly, larger deviations were observed when the CCSD method was applied.

For selected compounds, the crucial bond strength was determined in two different methods. The BDE of each stationary point anchored on the PES is determined by subtracting the electronic energy of the characterized stationary point from the sum of the two fully relaxed radical fragments (a∙ and b∙, respectively) following Equation (2).

BDE = EEa• + EEb• − EEab

In contrast, the Eint between two molecular fragments in this project was determined based on the fully characterized stationary point. For example, for a Lewis acid and base adduct AB, the Eint is determined following Equation (3), where and are the single-point electronic energies of the Lewis acid and base (denoted as A and B, respectively), according to the optimized electronic structure AB.

4. Conclusions

In this study, all gas-phase reactions involved in the InN MOVPE growth proposed in previous work were rigorously revisited utilizing the DFT method at the M06-2X/6-311G(d,p) level of theory. With a comprehensive analysis of thermodynamics, ESP, NBO and Mulliken charge distribution, reaction mechanisms of pivotal gas reaction paths were conducted to elucidate the reaction mechanisms of key gas reaction pathways from a microscopic viewpoint. Based on our theoretical findings, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- Negligible differences were observed when comparing the electronic structures optimized using double-ζ and triple-ζ split-valence basis set, the bond lengths differ by less than 0.5% and the bond angles were within a 0.85% deviation. Similarly, the same trend was also observed when analyzing the reaction energetics, as the changes in enthalpies and activation energies were within 1.2 kJ/mol and 1.3 kJ/mol, respectively. Thus, it is reasonable to believe that when applied with the M06-2X function, a double-ζ basis set can provide reliable predictions and thereby present a viable option to achieve an optimized balance between computation cost and accuracy.

- Although it is believed that adduct formation and the XMIn pyrolysis reactions are one-step reactions that do not involve any TSs, there has been no computation verification of this assertion to the best of our knowledge. In this study, rigorous constrained geometry optimizations were utilized to scan the PES connecting the reactants and products in adduct formation (A1–A1b) and XMIn pyrolysis (P4–P4b), confirming that there are indeed no TSs for these reactions.

- The NBO analyses verified the coordinate nature of In-N bond in TMIn:NH3. In contrast, computational results indicate that no bond interaction was observed between the N and the In in DMIn:NH3 and MMIn:NH3. Through a comprehensive analysis based on Eint, BDE, Mayer bond orders and Mulliken charge transfer, the bond strength follows the trend: DMIn:NH2 > MMIn(NH2)2 > TMIn:NH3 > DMIn:NH3 > MMIn:NH3. Additionally, the Mayer bond orders of the In-N bond in TMIn:NH3, DMIn:NH3, MMIn:NH3, DMInNH2, and MMIn(NH2)2 are 0.205, 0.198, 0.142, 0.91, and 0.85, respectively, suggesting that the In–N interaction in DMInNH2 and MMIn(NH2)2 is close to a single bond.

- The NBO analysis of XMIn (X = M, D, T) revealed that the valence electrons of the In atom in both TMIn and MMIn are bonded with methyl groups or have paired-up electrons, while the In in DMIn retains one unpaired electron. Thus, the complexity of XMIn pyrolysis could be attributed to electron multiplicity. During the pyrolysis of XMIn, the involvement of the highly reactive H radical facilitates electron transfer. Migration of the electrons that originally distribute between In-C bonds in XMIn cause bond cleavage and thus boost the XMIn pyrolysis.

- In contrast to the results reported in previous work, the H radical is attracted to the electron-proficient N in MMInNH2, resulting in the formation of MMIn:NH3 rather than MMInHNH2. Subsequently, MMIn:NH3 can undergo elimination reactions and release CH4 through two parallel paths: one being the irreversible decomposition of A2b, and the other referred to as the “H-shift” path. In the latter, MMIn:NH3 can transform into MMInHNH2 through H-shift, followed by CH4 elimination via reaction R9. A comparison of the Ea for these two competing pathways indicates that the former path is the dominant one.

- Given the substantial presence in the gas phase, H2 may react with the electron-proficient C in CH3 in XMIn (X = M, D, T) through reactions H12–H14. When undergoing these reactions, the electrons mainly transfer from one H atom to another H atom intramolecularly, leading to the cleavage of the H-H bond in H2. To shed light on the difference in Ea in H12–H14, the total number of electron transfers for In-C bond cleavage is calculated and the number follows the trend:H14 > H12 > H13, which aligns with the trend of Ea in H12–H14.

- Mulliken charge distribution analysis indicated that while forming the tetragonal cyclic dimer (DMInNH2)2, intermolecular electron transfer between two DMInNH2 molecules predominately takes place between an In atom in the firstDMInNH2 and an N atom in the other. In contrast, during trimerization reaction O11, electron transfer primarily occurs intramolecularly from the In atom to the N atom within the same DMInNH2.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules30040971/s1. Table S1. A comparison of selected bond lengths (in Å) of pivotal molecules analyzed in this study; Table S2. Comparison of selected bond angles (in °) of pivotal molecules computed in this study; Table S3. Nature bond orbitals of DMIn:NH3; Table S4. Nature bond orbitals of MMIn:NH3; Table S5. Nature bond orbitals of In-C bond of XMIn (X = M, D, T); Table S6. The occupancy of the bonds in characterized TSs in H radical-involved pyrolysis reaction path; Table S7. Nature bond orbitals of MMInHNH2; Table S8. Nature bond orbitals of DMInNH2, (DMInNH2)2 and (DMInNH2)3; Table S9. The enthalpy change (∆H, in kJ/mol) of reaction A1 (TMIn+NH3↔TMIn:NH3) and the enthalpy change deviation (Dev∆H, in kJ/mol) with its percent deviation results obtained at different ab initio and DFT levels of theory; Figure S1. The optimized structure of TSs in H-involved XMIn (X = M, D, T) pyrolysis reaction; Figure S2. The ESP map of MMInNH2; Figure S3. The Mulliken charge distribution of MMInHNH2 and corresponding TS in reaction R9; Figure S4. The ESP map of H2 and XMIn (X = M, D, T); Figure S5. Structure parameters in XMIn (X = M, D, T) and corresponding XMIn + H2 TS; Figure S6. Mulliken charge on the key atoms in XMIn (X = M, D, T) and corresponding XMIn + H2 TS.

Author Contributions

Software, conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing, X.H.; investigation, N.X.; conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing, Y.X.; investigation, H.Z.; validation, R.Z.; project administration and funding acquisition, Q.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the High-Tech Key Laboratory of Zhenjiang City (No. SS2018002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

Y.X acknowledges technical help and support from the Ohio Supercomputer Center (OSC) for the computational grant POBC0041 and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, J.; Walukiewicz, W.; Yu, K.M.; Ager Iii, J.W.; Haller, E.E.; Lu, H.; Schaff, W.J.; Saito, Y.; Nanishi, Y. Unusual properties of the fundamental band gap of InN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 80, 3967–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclaughlin, D.V.P.; Pearce, J.M. Progress in indium gallium nitride materials for solar photovoltaic energy conversion. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2013, 44, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Schmid, R.; Müller, J.; Fischer, R.A. Materials chemistry of group 13 nitrides. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 9, 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, I.M. Metal organic vapour phase epitaxy of AlN, GaN, InN and their alloys: A key chemical technology for advanced device applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2120–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauelsberg, M.; Talalaev, R. Progress in modeling of III-nitride MOVPE. J. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 2020, 66, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, D.; Mazumder, S.; Kuykendall, W.; Lowry, S.A. Combined ab initio quantum chemistry and computational fluid dynamics calculations for prediction of gallium nitride growth. J. Cryst. Growth 2005, 279, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Tang, B.H.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Y.M. Review of research on AlGaN MOVPE growth. J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 024009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simka, H.; Willis, B.G.; Lengyel, I.; Jensen, K.F. Computational chemistry predictionsof reaction processesin organometallic vapor phase epitaxy. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 1997, 35, 117–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zuo, R.; Zhang, G.Y. Effects of reaction-kinetic parameters on modeling reaction pathways in GaN MOVPE growth. J. Cryst. Growth 2017, 478, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.T.; Creighton, J.R. Complex formation of trimethylaluminum and trimethylgallium with ammonia: Evidence for a hydrogen-bonded adduct. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, A.K.; Gueorguiev, G.K.; Stafström, S.; Hultman, L.; Janzén, E. AlGaInN metal-organic-chemical-vapor-deposition gas-phase chemistry in hydrogen and nitrogen diluents: First-principles calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 431, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacko, M.G.; Price, S.J.W. The pyrolysis of trimethyl gallium. Can. J. Chem. 1963, 41, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacko, M.G.; Price, S.J.W. The pyrolysis of trimethyl indium. Can. J. Chem. 1964, 42, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Park, C.; Jung, J.H.; Anderson, T.J. Homogeneous decomposition of trimethylindium in an inverted, stagnation-point flow reactor by in situ Raman spectroscopy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2008, 155, H124–H129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihopoulos, T.G. Reaction and Transport Processes in OMCVD: Selective and Group III-Nitride Growth; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton, J.R.; Wang, G.T.; Breiland, W.G.; Coltrin, M.E. Nature of the parasitic chemistry during AlGaInN OMVPE. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 261, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Makino, O.; Tachibana, A.; Matsumoto, K. Quantum chemical study of parasitic reaction in III–V nitride semiconductor crystal growth. J. Organomet. Chem. 2000, 611, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, J.R.; Wang, G.T.; Coltrin, M.E. Fundamental chemistry and modeling of group-III nitride MOVPE. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 298, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallotti, C.; Moscatelli, D.; Masi, M.; Carrà, S. Accelerated decomposition of gas phase metal organic molecules determined by radical reactions. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 266, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Xue, Y.; Zuo, R. Gas phase reaction mechanism of InN MOVPE: A systematic DFT study. J. Cryst. Growth 2023, 612, 127197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Musgrave, C.B. Comparison of DFT methods for molecular orbital eigenvalue calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 1554–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, R.P.; Adomaitis, R.A. An overview of gallium nitride growth chemistry and its effect on reactor design: Application to a planetary radial-flow CVD system. J. Cryst. Growth 2006, 286, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J.S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadt, W.R.; Hay, P.J. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troullier, N.; Martins, J.L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 43, 8861–8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuku, K. The path of chemical reactions-the IRC approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 1981, 14, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, C.; Plesset, M.S. Note on an approximation treatment for many electron systems. Phys. Rev. 1934, 46, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cížek, J. Advances in Chemical Physics; Hariharan, P.C., Ed.; Wiley Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 14, p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, G.D., III; Bartlett, R.J. A full coupled-cluster singles and doubles model—The inclusion of disconnected triples. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 76, 1910–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuseria, G.E.; Janssen, C.L.; Schaefer, H.F., III. An efficient reformulation of the closed-shell coupled cluster single and double excitation (CCSD) equations. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 7382–7387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuseria, G.E.; Schaefer, H.F., III. Is coupled cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) more computationally intensive than quadratic configuration-interaction (QCISD)? J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 3700–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).