Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of a ZnO-Loaded Isoreticular Metal-Organic Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

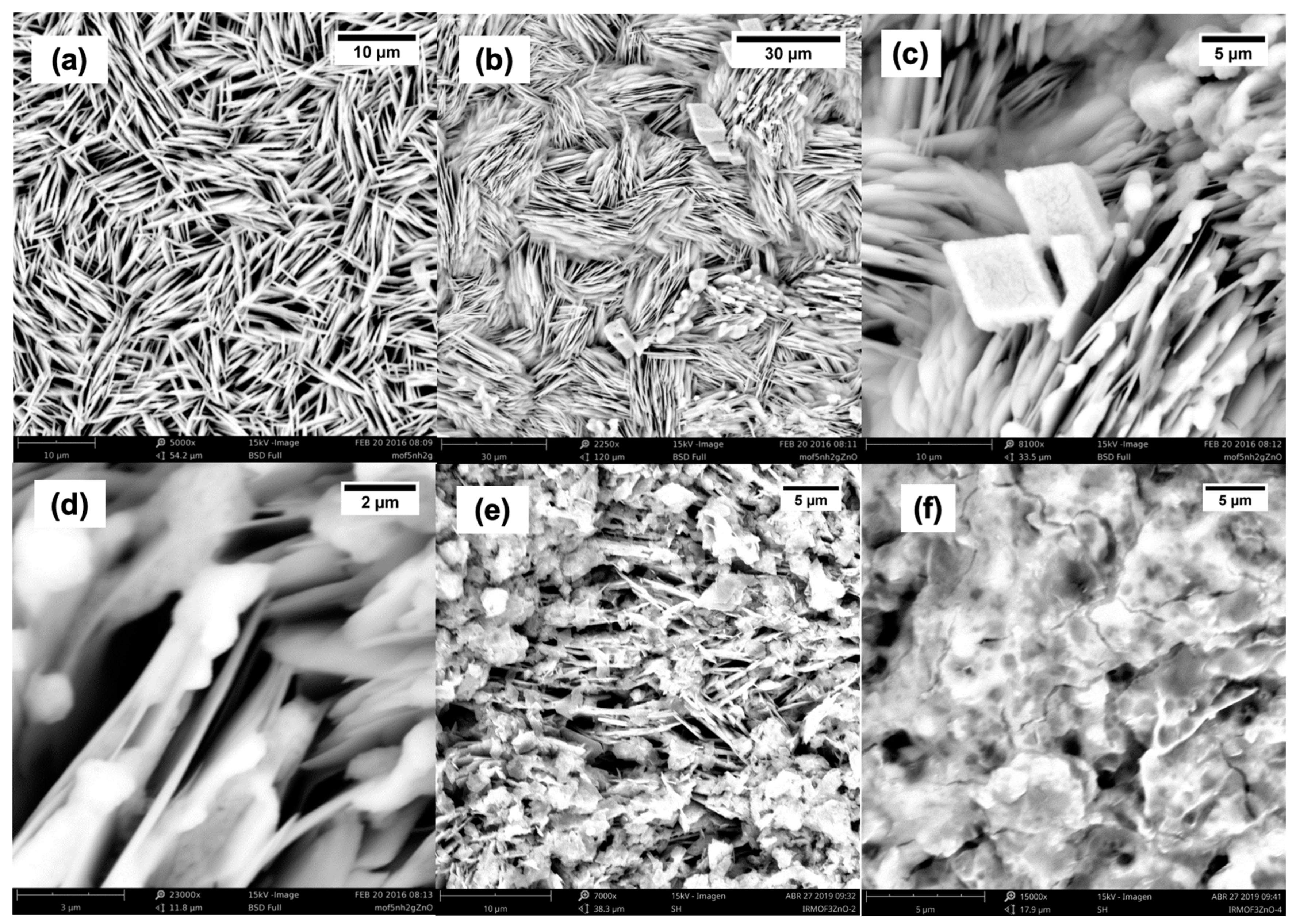

2.1. SEM Characterization

2.2. FTIR Characterization

2.3. Theoretical Calculations

2.4. XRD Characterization

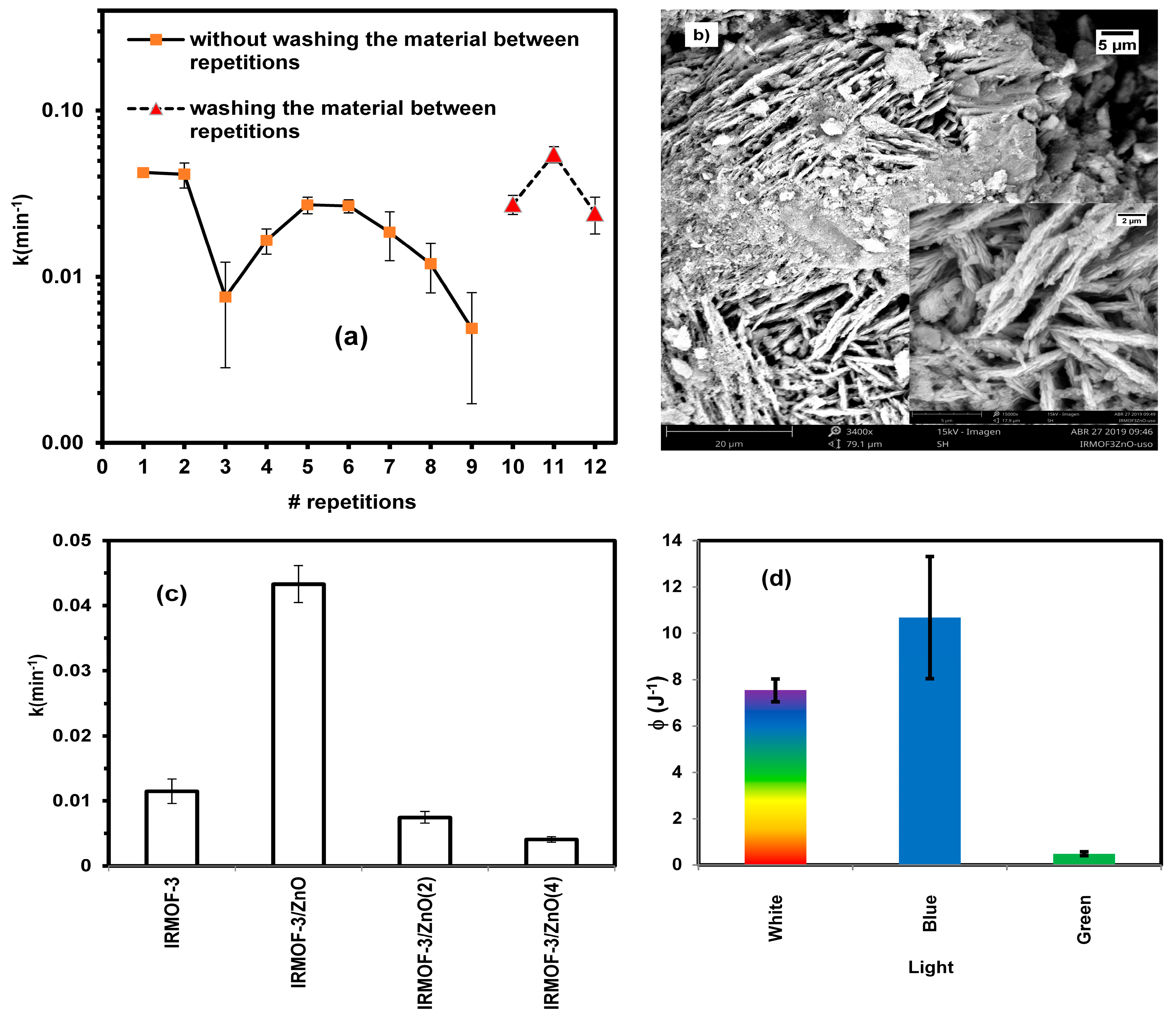

2.5. Band-Gap Determination

2.6. Artificial Photoreaction and Adsorption-Photodegradation Measurements

2.7. Effect of Catalyst Concentration

2.8. Catalyst Reuse Capacity

2.9. Effect of Multiple Impregnations of IRMOF with ZnO

2.10. Dependence of Photocatalytic Activity on Light Energy

2.11. Comparison with Other Visible-Light Photocatalytic Systems

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. IRMOF-3 Synthesis

3.2. ZnO-Functionalized IRMOF-3

3.3. Catalyst Characterization

3.4. Metodology for Adsorption-Photodegradation Measurements

3.5. Effect of Catalyst Concentration Methodology

3.6. Catalyst Recyclability

3.7. Effect of Multiple ZnO Impregnations

3.8. Effect of Light Energy on Photodegradation Efficiency

3.9. Theoretical Calculations Methodology

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MOFs | Metal-organic frameworks |

| IRMOF-3 | basic isoreticular metal-organic framework |

| 3DGN | 3D graphene network |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| MB | methylene blue |

| 2-AT | 2-aminoterephthalic acid |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ESP | electrostatic surface potentials |

References

- UNESCO. Agua Para Todos, Agua Para la Vida; Naciones Unidas: Paris, Francia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gajbhiye, S.B. Photocatalytic degradation study of methylene blue solutions and its application to dye industry effluent. Int. J. Mod. Eng. Res. 2012, 2, 1204–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Hassena, H. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Mod. Chem. Appl. 2016, 4, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Cortazar, A.; Coronal, C.; Escalante, A.; Gonzalez, R. Contaminación generada por colorantes de la industria textil. Univ. Autón. Estado Hidalgo 2010, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, A.; Figueroa, D.; Hormaza, A. Adsorption of methylene blue on rice hulls. Prod. Limpia 2012, 17, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyave Rojas, J.A.; Rodríguez Gaviria, E.M.; Barón Aristizábal, C.A.; Moreno Salazar, C.C. Degradación y mineralización del colorante rojo punzó empleando el reactivo de Fenton. Prod. Limpia 2012, 7, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, R.P.; Freitas, T.K.; Domingues, F.S.; Pezoti, O.; Ambrosio, E.; Ferrari-Lima, A.M.; Garcia, J.C. Photocatalytic activity of Ti2, ZnO and Nb2O5 applied to degradation of textile wastewater. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2016, 329, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, G.; Pillans, J.J.; Hatton, A.D.; Upstill-Goddard, R.C. Photochemical oxidation of dimethylsulphide to dimethylsulphoxide in estuarine and coastal waters. Chemosphere 2017, 186, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankaraiah, G.; Saritha, P.; Bhagawan, D.; Himabindu, V.; Vidyavathi, S. Photochemical oxidation of antibiotic gemifloxacin in aqueous solutions—A comparative study. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 24, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyol, A.; Can, O.T.; Bayramoglu, M. Treatment of hydroquinone by photochemical oxidation and electrocoagulation combined process. J. Water Process Eng. 2015, 8, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Xu, Y.; Jia, L. Effects of inorganic seeds on secondary organic aerosol formation from photochemical oxidation of acetone in a chamber. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 170, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martín, Á.; Caballero, A.; Colón, G. Photochemical methane partial oxidation to methanol assisted by H2O2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 349, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Takizawa, S.-Y.; Murata, S. Photochemical water oxidation system using ruthenium catalysts embedded into vesicle membranes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2016, 321, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, S.D.M.; de Oliveira, M.G. Topical photochemical nitric oxide release from porous poly(vinyl alcohol) membrane for visible light modulation of dermal vasodilation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 346, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, X. Robust photoelectrocatalytic degradation of antibiotics by organic-inorganic PDISA/Bi2WO6 S-scheme heterojunction membrane. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ye, Y.; Xu, L.; Gao, T.; Zhong, A.; Song, Z. Recent Advances in Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron (nZVI)-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs): Applications, Mechanisms, and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Ye, Y.; Ye, J.; Gao, T.; Wang, D.; Chen, G.; Song, Z. Recent Advances of Magnetite (Fe3O4)-Based Magnetic Materials in Catalytic Applications. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, S.; Olivero, J.; Pacheco, L.; Pulgarin, C. Structural properties and photoreactivity relationships of substituted phenols in TiO2 suspensions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2003, 43, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Aplicación de la Fotocatálisis Solar a la Degradación de Contaminantes Orgánicos con Catalizadores Nanoestructurados de TiO2; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, M.J.; Navarro, C.; Durán, P.; Galan-Freyle, N.J.; Parra Hernández, L.A.; Pacheco-Londoño, L.C.; Castelanich, D.; Bermúdez, V.; Chacin, M. Antioxidants in Photoaging: From Molecular Insights to Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatamian, M.; Daneshvar, N.; Sabaee, S. Heterogeneos Photocatalytic Decolorization of Brown NG by TiO2–UV Process. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2010, 29, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabadi, Z.; Faghihian, H. Comparative photocatalytic performance of TiO2 supported on clinoptilolite and TiO2/Salicylaldehyde-NH2-MIL-101(Cr) for degradation of pharmaceutical pollutant atenolol under UV and visible irradiations. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 356, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutiti, A.; Zouaghi, R.; Bendjabeur, S.E.; Guittonneau, S.; Sehili, T. Photodegradation of 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium by UV/H2O2 and UV/TiO2: Influence of pH and chloride. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 336, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica, E.; Natera, J.; Pajares, A.; Gambetta, C.; Sancho, M.I.; Massad, W.A.; García, N.A. Cyclodextrine-nanoencapsulation of niclosamide: Water solubility and meaningful enhancement of visible-light—Mediated sensitized photodegradation of the drug. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 348, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.N.; Jung, H.-R.; Lee, W.-J. Hollow cobalt ferrite–polyaniline nanofibers as magnetically separable visible-light photocatalyst for photodegradation of methyl orange. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2016, 321, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, Z.; Arnoux, P.; Colombeau, L.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Frochot, C.; Roques-Carmes, T. Comparison of two procedures for the design of dye-sensitized nanoparticles targeting photocatalytic water purification under solar and visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 356, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.-M.; Quek, J.-A.; Sin, J.-C. Mechanistic investigation of visible light responsive Ag/ZnO micro/nanoflowers for enhanced photocatalytic performance and antibacterial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 353, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, T.M.; El-Sheikh, S.M.; Hakki, A.; Ismail, A.A.; Badawy, W.A.; Bahnemann, D.W. Highly active non-metals doped mixed-phase TiO2 for photocatalytic oxidation of ibuprofen under visible light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 346, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liang, H.; Hong, J.; Wang, Z. Hydrothermal synthesis of cobalt-doped ZnS for efficient photodegradation of methylene blue. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2016, 325, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayadi, R.A.; Bakar, F.A. Comparative study on the performance of Au/F-TiO2 photocatalyst synthesized from Zamzam water and distilled water under blue light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 346, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-Y.; Yuann, J.-M.P.; Hsie, Z.-J.; Huang, S.-T.; Chen, C.-C. Blue light induced free radicals from riboflavin in degradation of crystal violet by microbial viability evaluation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 174, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzechulska, J.; Morawski, A.W. Photocatalytic decomposition of azo-dye acid black 1 in water over modified titanium dioxide. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2002, 36, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ökte, A.N.; Karamanis, D.; Chalkia, E.; Tuncel, D. The effect of ZnO or TiO2 loaded nanoparticles on the adsorption and photocatalytic performance of Cu-BTC and ZIF-8 MOFs. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 187, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Z.; Zhang, R.; Jiao, L.; Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic framework-derived porous materials for catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 362, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buasakun, J.; Srilaoong, P.; Chaloeipote, G.; Rattanakram, R.; Wongchoosuk, C.; Duangthongyou, T. Synergistic effect of ZnO/ZIF8 heterostructure material in photodegradation of methylene blue and volatile organic compounds with sensor operating at room temperature. J. Solid State Chem. 2020, 289, 121494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-T.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, K.-S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.-L.; Su, Z.-M.; Xie, H.-M. Metal–Organic Framework with Aromatic Rings Tentacles: High Sulfur Storage in Li–S Batteries and Efficient Benzene Homologues Distinction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 33183–33188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreno, L.E.; Leong, K.; Farha, O.K.; Allendorf, M.; Van Duyne, R.P.; Hupp, J.T. Metal–Organic Framework Materials as Chemical Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1105–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-J.; Lu, P.; Culp, J.T.; Ohodnicki, P.R. Metal-Organic Framework Thin Film Coated Optical Fiber Sensors: A Novel Waveguide-Based Chemical Sensing Platform. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, B.; He, H.; Zhou, W.; Chen, B.; Qian, G. Metal–Organic Frameworks as Platforms for Functional Materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Medina, J.; Mass-González, G.; Pacheco-Londoño, L.; Hernández-Rivera, S.P.; Fu, R.; Hernández-Maldonado, A.J. Long and local range structural changes in M[(bdc)(ted)0.5] (M = Zn, Ni or Cu) metal organic frameworks upon spontaneous thermal dispersion of LiCl and adsorption of carbon dioxide. Microp. Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 212, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, M.; Yang, P.; Asiri, A.M.; Wang, X. Metal–organic frameworks for solar energy conversion by photoredox catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 373, 83–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Luo, Z.-D.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl violet and rhodamine B based on an extremely stable metal-organic framework decorated with carboxylate groups. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2017, 85, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanalizadeh, H.; Manteghi, F. Immobilization of mixed cobalt/nickel metal-organic framework on a magnetic BiFeO3: A highly efficient separable photocatalyst for degradation of water pollutions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017, 346, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, Y.; Feng, J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, L.; Dan, Y.; Qiu, Y. Charge transfer induced unexpected red-shift absorption of Zn and Cu porous coordination polymers based on electron-withdrawing ligand. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 350, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, Y.; Toyao, T.; Saito, M.; Mochizuki, K.; Iwata, M.; Higashimura, H.; Anpo, M.; Matsuoka, M. Visible-Light-Promoted Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production by Using an Amino-Functionalized Ti(IV) Metal–Organic Framework. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 20848–20853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhang, X.; Xie, K.; Zhang, X.-F.; Feng, Y.; Jia, M.; Yao, J. Noble metal nanoparticle-functionalized Zr-metal organic frameworks with excellent photocatalytic performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 538, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahata, P.; Madras, G.; Natarajan, S. Novel photocatalysts for the decomposition of organic dyes based on metal-organic framework compounds. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 13759–13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Li, J.-R.; Lv, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Guo, G. Photocatalytic organic pollutants degradation in metal–organic frameworks. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2831–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehifar, N.; Zarghami, Z.; Ramezani, M. A facile, novel and low-temperature synthesis of MgO nanorods via thermal decomposition using new starting reagent and its photocatalytic activity evaluation. Mater. Lett. 2016, 167, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Zhang, C.; Sun, H.; Liu, S.; Tadé, M.; Wang, S. Photocatalysis of C, N-doped ZnO derived from ZIF-8 for dye degradation and water oxidation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 95903–95909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zheng, B.; Rui, X.; Shi, W.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, H. Metal oxide-coated three-dimensional graphene prepared by the use of metal-organic frameworks as precursors. Angew. Chem. (Int. Ed. Engl.) 2014, 53, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shen, K.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. Hollow-ZIF-templated formation of a ZnO@C–N–Co core–shell nanostructure for highly efficient pollutant photodegradation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 9937–9945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L. Microwave assisted synthesis of reduced graphene oxide incorporated MOF-derived ZnO composites for photocatalytic application. Catal. Commun. 2017, 88, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew Lin, K.-Y.; Hsu, F.-K. Magnetic iron/carbon nanorods derived from a metal organic framework as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for the chemical oxidation process in water. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 50790–50800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ye, F.; Shen, S.; Xiong, Y.; Su, L.; Zhao, S. From metal–organic frameworks to magnetic nanostructured porous carbon composites: Towards highly efficient dye removal and degradation. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 8228–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, M.; Hu, Z.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, D. Highly efficient photocatalysts by pyrolyzing a Zn–Ti heterometallic metal–organic framework. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 4046–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Forster, M.; Jin, J.; Myers, P.; Zhang, H. Tuning Morphology of Nanostructured ZIF-8 on Silica Microspheres and Applications in Liquid Chromatography and Dye Degradation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 18054–18063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Cheng, J.K.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Q.; Kang, Z.; Zhao, D. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as precursors towards TiOx/C composites for photodegradation of organic dye. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 34221–34225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.J.; Im, J.H.; Kim, T.; Lee, K.; Park, C.R. MOF-derived ZnO and ZnO@C composites with high photocatalytic activity and adsorption capacity. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ai, L.; Jiang, J. Solvothermal synthesis of MIL–53(Fe) hybrid magnetic composites for photoelectrochemical water oxidation and organic pollutant photodegradation under visible light. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 3074–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Oh, S.; Lee, S.; Choi, S.; Oh, M. Cobalt- and nitrogen-codoped porous carbon catalyst made from core–shell type hybrid metal–organic framework (ZIF-L@ZIF-67) and its efficient oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 246, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakare, S.R.; Ramteke, S.M. Postmodification of MOF-5 using secondary complex formation using 8-hydroxyquinoline (HOQ) for the development of visible light active photocatalysts. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2018, 116, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tang, B.; Long, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Mirza, Z. The development of MOFs-based nanomaterials in heterogeneous organocatalysis. Sci. Bull. 2018, 63, 502–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera-Sigalat, J.; Bradshaw, D. Synthesis and applications of metal-organic framework–quantum dot (QD@MOF) composites. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 307, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Hermes, S.; Kähler, K.; van den Berg, M.W.E.; Muhler, M.; Fischer, R.A. Loading of MOF-5 with Cu and ZnO Nanoparticles by Gas-Phase Infiltration with Organometallic Precursors: Properties of Cu/ZnO@MOF-5 as Catalyst for Methanol Synthesis. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 4576–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chowdhuri, A.R.; Kumari, A.; Sahu, S.K. IRMOF-3: A fluorescent nanoscale metal organic frameworks for selective sensing of glucose and Fe (III) ions without any modification. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 92, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, K.K.; Wang, Z.; Cohen, S.M. Systematic Functionalization of a Metal−Organic Framework via a Postsynthetic Modification Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8508–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; McNamara, N.D.; Her, T.H.; Hicks, J.C. Carbothermal Reduction of Ti-Modified IRMOF-3: An Adaptable Synthetic Method to Support Catalytic Nanoparticles on Carbon. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 11479–11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, D.; Sen, R.; Maity, T.; Koner, S. Anchoring of Palladium onto Surface of Porous Metal–Organic Framework Through Post-Synthesis Modification and Studies on Suzuki and Stille Coupling Reactions Under Heterogeneous Condition. Langmuir 2013, 29, 3140–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Bhardwaj, S.; Mehta, J.; Kim, K.H.; Deep, A. Highly sensitive detection of dipicolinic acid with a water-dispersible terbium-metal organic framework. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Su, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Dai, X.; Gao, J.; Chen, C.; Sun, S.-G. Fe/IRMOF-3 derived porous carbons as non-precious metal electrocatalysts with high activity and stability towards oxygen reduction reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 205, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.D.; Park, G.A.; Kim, D.W.; Park, D.W. Catalytic performance of functionalized IRMOF-3 for the synthesis of glycerol carbonate from glycerol and urea. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 4551–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, G. Functionalized IRMOF-3 as efficient heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of cyclic carbonates. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2012, 361–362, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhuri, A.R.; Singh, T.; Ghosh, S.K.; Sahu, S.K. Carbon Dots Embedded Magnetic Nanoparticles @Chitosan @Metal Organic Framework as a Nanoprobe for pH Sensitive Targeted Anticancer Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 16573–16583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karra, J.R.; Walton, K.S. Molecular Simulations and Experimental Studies of CO2, CO, and N2 Adsorption in Metal−Organic Frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 15735–15740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Dong, Q.; Hu, J.; Xiao, W.; Liu, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, N. Enhanced selective adsorption of CO2 on nitrogen-doped porous carbon monoliths derived from IRMOF-3. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 9757–9760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmatkesh, M.; Ebrahimi, S. Biodegradation of Reactive orange 16 by Phanerochaete chrysosporium fungus: Application in a fluidized bed bioreactor. Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2010, 7, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M.; Lessin, M.S.; Gilchrist, B.F. Methylene blue: Dangerous dye for neonates. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2003, 38, 1244–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Tahir, H.; Uddin, F.; Hameed, U. Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution on the surface of wool fiber and cotton fiber. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2005, 9, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Phaltane, S.A.; Vanalakar, S.A.; Bhat, T.S.; Patil, P.S.; Sartale, S.D.; Kadam, L.D. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by hydrothermally synthesized CZTS nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 8186–8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Harada, M.; Misaka, J.; Takeuchi, M.; Neppolian, B.; Anpo, M. Photocatalytic degradation of organic compounds diluted inwater using visible light-responsive metal ion-implanted TiO2 catalysts: Fe ion-implanted TiO2. Catal. Today 2003, 84, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachfule, P.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Banerjee, R. Fluorinated Metal-Organic Frameworks: Advantageous for Higher H2 and CO2 Adsorption or Not? Chem. Eur. J 2012, 18, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Su, C.; Liu, H.; Zhu, F.; Jiang, R.; Ouyang, G. In situ growth of IRMOF-3 combined with ionic liquids to prepare solid-phase microextraction fibers. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 829, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isobe, T.; Arai, Y.; Yanagida, S.; Matsushita, S.; Nakajima, A. Solvothermal preparation and gas permeability of an IRMOF-3 membrane. Microp. Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 241, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-R.; Cho, S.-M.; Ahn, W.-S.; Lee, C.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; Cho, W.-S. Facile synthesis of an IRMOF-3 membrane on porous Al2O3 substrate via a sonochemical route. Microp. Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 213, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong Lin, W. Zinc oxide nanostructures: Growth, properties and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2004, 16, R829. [Google Scholar]

- Dan-Hardi, M.; Serre, C.; Frot, T.; Rozes, L.; Maurin, G.; Sanchez, C.; Férey, G. A New Photoactive Crystalline Highly Porous Titanium(IV) Dicarboxylate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10857–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, H.Q.; Mai, T.; Pham-Tran, N.-N.; Kawazoe, Y.; Mizuseki, H.; Nguyen-Manh, D. Engineering of Band Gap in Metal–Organic Frameworks by Functionalizing Organic Linker: A Systematic Density Functional Theory Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 4567–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, R.M.; Carlos, L.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Rocha, J. Engineering lanthanide-optical centres in IRMOF-3 by post-synthetic modification. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 4249–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Zacher, D.; Zhang, X.; Fischer, R.A.; Metzler-Nolte, N. A Method for the Preparation of Highly Porous, Nanosized Crystals of Isoreticular Metal−Organic Frameworks. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-L.; Fan, H.-L.; Tian, Z.; He, E.-Y.; Li, Y.; Shangguan, J. Adsorptive removal of sulfur compounds using IRMOF-3 at ambient temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 289, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Deng, K.; He, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, H.; Tang, Z. Core–Shell Palladium Nanoparticle@Metal–Organic Frameworks as Multifunctional Catalysts for Cascade Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 1738–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Jeong, H.-K. Heteroepitaxial Growth of Isoreticular Metal−Organic Frameworks and Their Hybrid Films. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| IRMOF-3/ZnO | IRMOF-3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrations (g*L−1) | k (min−1) | Half-Life Time (min) | k (min−1) | Half-Life Time (min) |

| 10.0 | 0.043 ± 0.003 | 16 | 0.011 ± 0.002 | 60 |

| 5.0 | 0.011 ± 0.003 | 65 | 0.008 ± 0.005 | 87 |

| 0.5 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 206 | 0.005 ± 0.003 | 131 |

| 0.1 | 0.005 ± 0.003 | 131 | ||

| 0.0 | 0.00047 ± 0.00001 | 1490 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas-Forero, A.Y.; Hernández-Benítez, L.Y.; Ospina-Castro, M.L.; Galán-Freyle, N.J.; Castro-Suarez, J.R.; Méndez-López, M.; Hernández-Rivera, S.P.; Centeno-Ortiz, J.A.; Romero-Nieto, S.P.; Pacheco-Londoño, L.C. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of a ZnO-Loaded Isoreticular Metal-Organic Framework. Molecules 2025, 30, 1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30061375

Rojas-Forero AY, Hernández-Benítez LY, Ospina-Castro ML, Galán-Freyle NJ, Castro-Suarez JR, Méndez-López M, Hernández-Rivera SP, Centeno-Ortiz JA, Romero-Nieto SP, Pacheco-Londoño LC. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of a ZnO-Loaded Isoreticular Metal-Organic Framework. Molecules. 2025; 30(6):1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30061375

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas-Forero, Ana Y., Laura Y. Hernández-Benítez, María L. Ospina-Castro, Nataly J. Galán-Freyle, John R. Castro-Suarez, Maximiliano Méndez-López, Samuel P. Hernández-Rivera, José A. Centeno-Ortiz, Sandra P. Romero-Nieto, and Leonardo C. Pacheco-Londoño. 2025. "Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of a ZnO-Loaded Isoreticular Metal-Organic Framework" Molecules 30, no. 6: 1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30061375

APA StyleRojas-Forero, A. Y., Hernández-Benítez, L. Y., Ospina-Castro, M. L., Galán-Freyle, N. J., Castro-Suarez, J. R., Méndez-López, M., Hernández-Rivera, S. P., Centeno-Ortiz, J. A., Romero-Nieto, S. P., & Pacheco-Londoño, L. C. (2025). Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of a ZnO-Loaded Isoreticular Metal-Organic Framework. Molecules, 30(6), 1375. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30061375