Abstract

In the past 17 years, three novel coronaviruses have caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). As emerging infectious diseases, they were characterized by their novel pathogens and transmissibility without available clinical drugs or vaccines. This is especially true for the newly identified COVID-19 caused by SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) for which, to date, no specific antiviral drugs or vaccines have been approved. Similar to SARS and MERS, the lag time in the development of therapeutics is likely to take months to years. These facts call for the development of broad-spectrum anti-coronavirus drugs targeting a conserved target site. This review will systematically describe potential broad-spectrum coronavirus fusion inhibitors, including antibodies, protease inhibitors, and peptide fusion inhibitors, along with a discussion of their advantages and disadvantages.

1. Introduction

The pandemic of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was caused by the novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) [1], also known as human coronavirus 2019 (HCoV-19) [2] or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [3]. It has posed a serious threat to global public health, as well as social and economic stability, thus calling for the development of highly effective therapeutics and prophylactics [4].

In its research and development blueprint, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the first list of prioritized diseases in 2015 and formally announced it on 9 February 2018 [5]. Apart from SARS and MERS, Disease X has sparked an international epidemic caused by an unknown pathogen that would be highly transmissible among humans. Jiang et al. suggested that the first reported pneumonia cluster in Wuhan in December of 2019, with its etiology unknown (later known as 2019-nCoV), should be recognized as the first Disease X [6]. However, this was the third coronavirus that has caused severe pneumonia in humans over the past twenty years. SARS-CoV infection resulted in 8096 cases and 774 deaths [7], whereas confirmed MERS cases numbered about 2494, including 858 deaths [8]. As of 25 April 2020, 2,724,809 COVID-19 cases and 187,847 deaths were confirmed [9], with no signs of abatement. As noted previously, vaccines and FDA-approved drugs still remain out of clinical reach. These facts call for the development of broad-spectrum anti-coronavirus drugs targeting a conserved target site that would address the current urgency and those coronavirus outbreaks that are likely to emerge in the future.

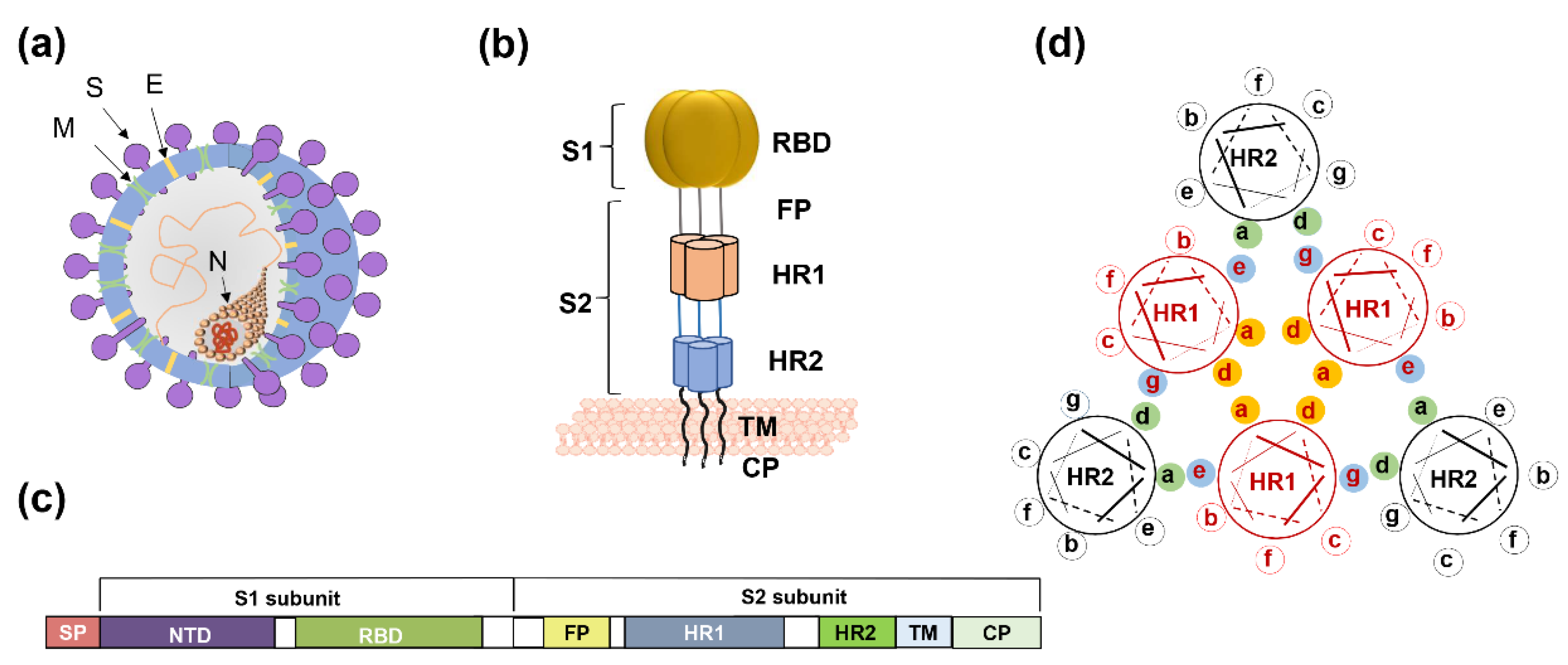

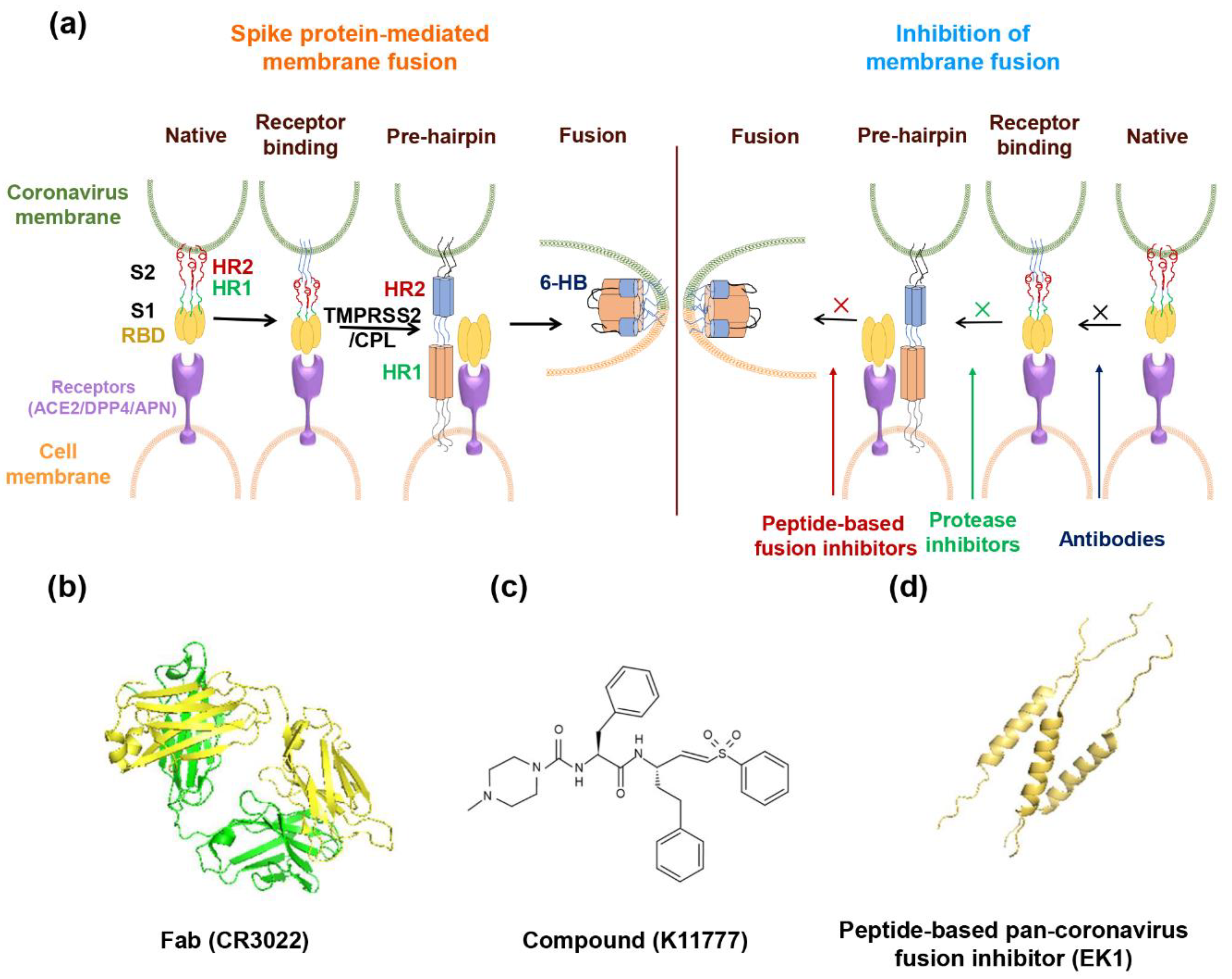

Coronaviruses (CoVs) comprise four genera—alphacoronavirus, betacoronavirus, gammacoronavirus, and deltacoronavirus. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to β-coronavirus. In this group, highly pathogenic SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV caused severe human diseases in 2002 and 2012, respectively [10,11]. The genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 is 79.5% homologous to SARS-CoV and 96% identical to bat SARS-related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV) [12,13]. Four low-pathogenicity coronaviruses are also epidemic in humans—HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1. The viral genome encodes four structural proteins, spike protein (S), membrane protein (M), envelope protein (E), and nucleocapsid protein (N) (Figure 1a). The S protein is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein, and it includes an extracellular domain, transmembrane domain, and intracellular domain. The extracellular domain of the S protein contains two subunits, S1 and S2, each playing a different role in receptor recognition, binding, and membrane fusion (Figure 1b). The S1 subunit includes the N-terminal domain (NTD) and C-terminal domain (CTD). Generally, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) is located in the CTD (Figure 1c). NTD mediates the binding between the virus and sugar-based receptors, and the CTD mediates viral binding to the protein-based receptor [14]. SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV utilize the CTD to bind their respective receptors. Receptor recognition and binding trigger membrane fusion between the virus and the target cell. We expect some conserved sites to be involved in these processes, in view of the fact that membrane fusion is an essential step for coronavirus infection of target cells. Taking membrane fusion as our focal point, this review will systematically describe broad-spectrum coronavirus fusion inhibitors, along with a discussion of their advantages and disadvantages.

Figure 1.

The spike protein of coronavirus and model of membrane fusion mechanism. (a) Cartoon figure of coronavirus structural protein. Three transmembrane proteins, spike protein (S; purple), membrane protein (M; green), envelop protein (E; yellow) are found on the surface of the coronavirus envelope. The nucleocapsid protein (N; orange) encapsulates the viral genome inside the virion. (b) Structure of the Spike protein. S protein contains two subunits, S1 and S2. S1 includes the receptor-binding domain (RBD; dark yellow). S2 includes the HR1 region (light orange) and the HR2 region (light blue). (c) The genomic region of complete coronavirus. (d) Interaction between HR1 and HR2. Residues located at the “a” and “d” positions in HR1 helices (shown as yellow circle shadow) interact to form an internal trimer; residues at “e” and “g” positions (blue shadow) interact with the residues at the “a” and “d” positions (green shadow) in the HR2 helices to form 6-HB.

2. The Mechanism of Membrane Fusion

2.1. Receptor Recognition and Binding

Receptor recognition by the S1 subunit of the spike protein of coronaviruses is the first step of viral infection [15], followed by RBD binding to the receptors. SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV use angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a receptor to mediate viral entry into target cells [12]. A study reported that the affinity of the ectodomain of SARS-CoV-2 S protein to ACE2 is 10- to 20-fold higher than that of SARS-CoV S protein [16]. However, another team revealed a similar ACE2 binding affinity between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV [17]. During the SARS-CoV infection, its spike protein could induce the down-regulation of ACE2 [18], while SARS-CoV-2 might share a similar mechanism to regulate ACE2 expression. Additionally, in COVID-19 patients, not all ACE2-expressing organs had similar level of pathophysiology, implying that some other mechanisms might also mediate the tissue damage; thus, further studies on the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 are warranted [19]. ACE2 is also the receptor of HCoV-NL63 [20]. HCoV-229E uses aminopeptidase N (APN) for cell entry [21], whereas MERS-CoV utilizes dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4, CD26) as its receptor [22], indicating the diversity of receptors among human coronaviruses. It is the interaction between RBD and the receptor that determines viral infection spectrum and host range [23]. Among the different genera, coronaviruses share low similarity in RBD sequence [24], which might explain the use of different receptors. The amino acid sequence in RBD of SARS-CoV-2 shares ~73% similarity with SARS-CoV and SARSr-CoVs (e.g., WIV1 and Rs3367), respectively, while it only has a 21% similarity with that of MERS-CoV [25]. Importantly, the RBD contains several neutralization epitopes that can serve as a target for the development of vaccines and antibodies [26,27,28,29]. At the same time, variation in the RBD limits the broad-spectrum property of vaccines and antibodies. Nonetheless, it is still possible to utilize the relatively conserved neutralization epitopes among the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, for research and development of broad-spectrum neutralizing antibodies, against lineage B β-CoVs, including SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and SARSr-CoVs.

2.2. Proteolytic Function in Membrane Fusion

In the natural state, S protein on the surface of coronavirus is inactive. Only after receptor binding and S protein priming by proteolysis of proteases is the S protein activated and fusion triggered [30]. The S2 subunit is then exposed to mediate membrane fusion. In all coronaviruses, a site called S2′ that is located upstream of the fusion peptide (FP) of the S protein, can be cleaved by the host protease [31,32]. At the boundary of the S1/S2 subunits, a study found that SARS-CoV-2 S protein contains a furin cleavage site that is cleaved during biosynthesis, which is different from SARS-CoV and SARSr-CoVs [17] but is similar to MERS-CoV [33]. The virus can enter into the target cell through two routes—direct fusion on the cellular surface and endocytosis. For the endocytosis route, the virus is encapsulated by the endosome after receptor binding. Then, the low pH environment promotes the cleavage of the S protein with pH-dependent cysteine protease cathepsin L (CPL). For direct fusion on the cellular membrane, transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) plays roles in cleavage and activation [34]. Some studies reported that SARS-CoV S protein could also be cleaved with human airway trypsin-like protease [34,35,36]. TMPRSS2 can also promote MERS-CoV entry into the target cell through the endocytosis pathway [37]. A recent study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 utilizes TMPRSS2 to activate the S protein and that a protease inhibitor could inhibit pseudovirus entry [38]. These studies suggest that coronaviruses have a similar proteolytic process and use the same protease, such as TMPRSS2. Therefore, suppressing the proteolysis of proteases might be a path toward the development of broad-spectrum fusion inhibitors.

2.3. Mechanism of S2 Subunit-Mediated Membrane Fusion

For coronaviruses, the S protein binding of receptor initially activates the entry process, resulting in membrane fusion and ensuring virus infection of the target cell. This mechanism was confirmed in SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [39,40]. After RBD binds to cellular receptors, the conformation of S2 subunits changes, followed by exposure of the fusion peptide into the cell membrane. S2 also includes the HR1 and HR2 regions that interact. Residues located at the “a” and “d” positions in the HR1 helices interact to form an internal trimer, and residues at the “e” and “g” positions interact with the residues at the “a” and “d” positions in the HR2 helices to form a six-helix bundle (6-HB) (Figure 1d). The 6-HB helps the viral membrane and cell membrane to come into close contact for viral fusion and entry.

In native conformation, the S2 subunit is buried inside the S1 subunit and only when fusion occurs, the S2 subunit is instantly exposed. Through sequence alignment, Xia et al. found that the S2 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 is highly conserved, in which the HR1 and HR2 domains share a 92.6% and 100% identity with those of SARS-CoV, respectively [41]. They designed two peptides derived from the HR1 and HR2 domains, 2019-nCoV-HR1P and 2019-nCoV-HR2P, respectively, and confirmed that they could interact with each other to form the coiled-coil complex, as shown by using native electrophoresis and circular dichroism. Through crystallographic analysis, the parallel trimeric coiled-coiled center formed by three HR1 domains was surrounded by three HR2 domains, in an antiparallel manner [34]. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 enters the target cell through membrane fusion in a 6-HB-dependent manner.

Therefore, coronaviruses appear to have a similar mechanism of membrane fusion, while HR1 and HR2 regions are highly conserved and can serve as important targets for development of broad-spectrum coronavirus fusion inhibitor-based drugs, for the treatment and prevention of coronavirus diseases.

5. Summary

The entry processes of a coronavirus include receptor recognition and binding, proteolytic cleavage of S protein, and S2 subunit-mediated membrane fusion. Each of these processes can serve as a target for the development of broad-spectrum drugs. Neutralizing antibodies that generally target the RBD in S protein have the advantages of high safety, stability, and efficacy; but the high variation of the RBD region among coronaviruses limits the development of broad-spectrum neutralizing antibodies. The high cost of production is another negative factor for their clinical applications. The small molecule compound-based entry inhibitors can be taken orally, with high acceptance. However, they are generatelly more toxic and less effective than antibodies and peptides in blocking virus entry through protein-protein interaction. Since many viruses use the proteases to mediate membrane fusion, they can be used as targets for development of broad-spectrum virus fusion inhibitors. However, they are human proteins and have their own functions in human bodies. Therefore, application of an inhibitor of the related enzyme might cause some side-effects. Peptide-based pan-CoV fusion inhibitors have shown great promise in the development of broad-spectrum prophylatics or therapeutics for the prevention and treatment of the current COVID-19, MERS, and other coronavirus diseases, as well as the emerging and reemerging coronavirus diseases that will occur in the future. Their target site, the HR1-trimer at the fusion intermediate state, is accessible to molecules less than 70 Kd. Therefore, the antibody is too big (~150 Kd) to access it, while the small molecule compound is too small to block the HR1–HR2 interaction. Moreover, it is safer than small molecule compounds and is more economical than antibodies. The weaknesses of a peptide drug include its short half-life and ability to induce antibodies against the peptide drugs. However, these antiviral peptide drugs are generally used in the early stage of the viral infection for a short period of time (e.g., 2–3 weeks) to save patients’ lives. Therefore, these weaknesses might not significantly affect their clinical use.

Author Contributions

X.W. and S.X. wrote the manuscript and depicted the figures. Q.W., W.X. and W.L. verified the data. S.J. and L.L. conceptualized and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Megaprojects of China for Major Infectious Diseases (2018ZX10301403 to L.L.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81822045 to L.L.; 81630090 to S.J.; 81703571 to W.X.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| SARS | Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| MERS | Middle East respiratory syndrome |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | SARS coronavirus 2 |

| 2019-nCoV | Novel coronavirus 2019 |

| HCoV-19 | Human coronavirus 2019 |

| SARSr-CoV | SARS-related coronavirus |

| NTD | N-terminal domain |

| CTD | C-terminal domain |

| RBD | Receptor-binding domain |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| APN | Aminopeptidase N |

| DPP4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| CPL | Cysteine protease cathepsin L |

| TMPRSS2 | Transmembrane protease serine 2 |

| FP | Fusion peptide |

| 6-HB | Six-helix bundle |

| PRNT | Plaque reduction neutralization test |

| IFITM | Interferon-inducible transmembrane |

| NM | Nafamostat mesylate |

| FOY | Ggabexate mesylate |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentration |

| CC50 | 50% cell cytotoxicity concentration |

| EC50 | Concentration for 50% of maximal effect |

| EC90 | Concentration for 90% of maximal effect |

| RAS | Renin-angiotensin system |

| AT2 | Angiotensin II receptor |

| pan-CoV | Pan-coronavirus |

References

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Jiang, S.; Shi, Z.; Shu, Y.; Song, J.; Gao, G.F.; Tan, W.; Guo, D. A distinct name is needed for the new coronavirus. Lancet 2020, 395, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Du, L.; Shi, Z. An emerging coronavirus causing pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, China: Calling for developing therapeutic and prophylactic strategies. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prioritizing Diseases for Research and Development in Emergency Contexts. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/prioritizing-diseases-for-research-and-development-in-emergency-contexts (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Jiang, S.; Shi, Z. The First Disease X Is Caused by a Highly Transmissible Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Virol. Sin. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, E.; van Doremalen, N.; Falzarano, D.; Munster, V.J. SARS and MERS: Recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). MERS Monthly Summary, November 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak Situation. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Cheng, V.C.; Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C.; Yuen, K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an agent of emerging and reemerging infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 660–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; Lau, S.K.; To, K.K.; Cheng, V.C.; Woo, P.C.; Yuen, K.Y. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus: Another Zoonotic Betacoronavirus Causing SARS-Like Disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 465–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Bidon, M.; Jaimes, J.A.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, E.; Ruiz-Jarabo, C.M.; Domingo, E. Evolution of cell recognition by viruses. Science 2001, 292, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.S.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292 e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuba, K.; Imai, Y.; Rao, S.A.; Gao, H.; Guo, F.; Guan, B.; Huan, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhang, Y.L.; Deng, W.; et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgonje, A.R.; Abdulle, A.E.; Timens, W.; Hillebrands, J.L.; Navis, G.J.; Gordijn, S.J.; Bolling, M.C.; Dijkstra, G.; Voors, A.A.; Osterhaus, A.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Pathol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Li, W.; Peng, G.; Li, F. Crystal structure of NL63 respiratory coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its human receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19970–19974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, C.L.; Ashmun, R.A.; Williams, R.K.; Cardellichio, C.B.; Shapiro, L.H.; Look, A.T.; Holmes, K.V. Human Aminopeptidase-N Is a Receptor for Human Coronavirus-229E. Nature 1992, 357, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.S.; Mou, H.; Smits, S.L.; Dekkers, D.H.; Muller, M.A.; Dijkman, R.; Muth, D.; Demmers, J.A.; Zaki, A.; Fouchier, R.A.; et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 2013, 495, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Receptor recognition and cross-species infections of SARS coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2013, 100, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Evidence for a Common Evolutionary Origin of Coronavirus Spike Protein Receptor-Binding Subunits. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 2856–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xia, S.; Wang, X.; Lan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, S.; Lu, L. Inefficiency of Sera from Mice Treated with Pseudotyped SARS-CoV to Neutralize 2019-nCoV Infection. Virol. Sin. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Zhao, G.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, H.; Wang, L.; Kou, Z.; Tao, X.; Yu, H.; Sun, S.; Tseng, C.T.; et al. A Conformation-Dependent Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibody Specifically Targeting Receptor-Binding Domain in Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7045–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Lu, H.; Siddiqui, P.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, S. Receptor-binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein contains multiple conformation-dependent epitopes that induce highly potent neutralizing antibodies. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 4908–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, J.; Li, W.; Murakami, A.; Tamin, A.; Matthews, L.J.; Wong, S.K.; Moore, M.J.; Tallarico, A.S.; Olurinde, M.; Choe, H.; et al. Potent neutralization of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus by a human mAb to S1 protein that blocks receptor association. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2536–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, B.; Jiang, S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV—A target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.M.; Whittaker, G.R. Fusion of Enveloped Viruses in Endosomes. Traffic 2016, 17, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, I.G.; Roth, S.L.; Belouzard, S.; Whittaker, G.R. Characterization of a Highly Conserved Domain within the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein S2 Domain with Characteristics of a Viral Fusion Peptide. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 7411–7421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Host cell proteases: Critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015, 202, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15214–15219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.Y.; Li, J.L.; Yang, X.L.; Chmura, A.A.; Zhu, G.; Epstein, J.H.; Mazet, J.K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2013, 503, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menachery, V.D.; Yount, B.L.; Sims, A.C.; Debbink, K.; Agnihothram, S.S.; Gralinski, L.E.; Graham, R.L.; Scobey, T.; Plante, J.A.; Royal, S.R.; et al. SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3048–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnest, J.T.; Hantak, M.P.; Li, K.; McCray, P.B., Jr.; Perlman, S.; Gallagher, T. The tetraspanin CD9 facilitates MERS-coronavirus entry by scaffolding host cell receptors and proteases. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiao, G.; Chen, Y.; He, Y.; Niu, J.; Escalante, C.R.; Xiong, H.; Farmar, J.; Debnath, A.K.; Tien, P.; et al. Interaction between heptad repeat 1 and 2 regions in spike protein of SARS-associated coronavirus: Implications for virus fusogenic mechanism and identification of fusion inhibitors. Lancet 2004, 363, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Chan, K.H.; Qin, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chan, J.F.; Du, L.; Yu, F.; et al. Structure-based discovery of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion inhibitor. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; Lan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, S.; et al. Fusion mechanism of 2019-nCoV and fusion inhibitors targeting HR1 domain in spike protein. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, L.; Li, F.; Jiang, S. MERS-CoV spike protein: A key target for antivirals. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huentelman, M.J.; Zubcevic, J.; Prada, J.A.H.; Xiao, X.D.; Dimitrov, D.S.; Raizada, M.K.; Ostrov, D.A. Structure-based discovery of a novel angiotensin converting enzyme 2 inhibitor. Hypertension 2004, 44, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Yan, L.; Xu, W.; Agrawal, A.S.; Algaissi, A.; Tseng, C.K.; Wang, Q.; Du, L.; Tan, W.; Wilson, I.A.; et al. A pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting the HR1 domain of human coronavirus spike. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Hua, C.; Li, W.; Lu, L.; Jiang, S. Peptide-Based Membrane Fusion Inhibitors Targeting HCoV-229E Spike Protein HR1 and HR2 Domains. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018, 19, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Chakraborti, S.; He, Y.; Roberts, A.; Sheahan, T.; Xiao, X.; Hensley, L.E.; Prabakaran, P.; Rockx, B.; Sidorov, I.A.; et al. Potent cross-reactive neutralization of SARS coronavirus isolates by human monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 12123–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockx, B.; Corti, D.; Donaldson, E.; Sheahan, T.; Stadler, K.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Baric, R. Structural basis for potent cross-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protection against lethal human and zoonotic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus challenge. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 3220–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, T.; Du, L.; Ju, T.W.; Prabakaran, P.; Lau, C.C.; Lu, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Exceptionally potent neutralization of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus by human monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7796–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Jiang, S.; Du, L. Advances in MERS-CoV Vaccines and Therapeutics Based on the Receptor-Binding Domain. Viruses 2019, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, R.; Pan, Z.; Qian, C.; Yang, Y.; You, R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, P.; Gao, L.; Li, Z.; et al. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Li, W.; Drabek, D.; Okba, N.M.; van Haperen, R.; Osterhaus, A.D.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.; Haagmans, B.L.; Grosveld, F.; Bosch, B.J. A human monoclonal antibody blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, J.; Voronin, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Du, L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Li, C.; Huang, A.; Xia, S.; Lu, S.; Shi, Z.; Lu, L.; Jiang, S.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; et al. Potent binding of 2019 novel coronavirus spike protein by a SARS coronavirus-specific human monoclonal antibody. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Qian, K.; Li, T.; Zhang, S.; Fu, W.; Ding, M.; Hu, S. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Kuba, K.; Rao, S.; Huan, Y.; Guo, F.; Guan, B.; Yang, P.; Sarao, R.; Wada, T.; Leong-Poi, H.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 2005, 436, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrone, T.; Magrone, M.; Jirillo, E. Focus on Receptors for Coronaviruses with Special Reference to Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2 as a Potential Drug Target—A Perspective. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrensch, F.; Winkler, M.; Pohlmann, S. IFITM Proteins Inhibit Entry Driven by the MERS-Coronavirus Spike Protein: Evidence for Cholesterol-Independent Mechanisms. Viruses-Basel 2014, 6, 3683–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, K.; Chu, H.; Liu, D.; Poon, V.K.; Chan, C.C.; Leung, H.C.; Fai, N.; Lin, Y.; et al. A novel peptide with potent and broad-spectrum antiviral activities against multiple respiratory viruses. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirato, K.; Kawase, M.; Matsuyama, S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection mediated by the transmembrane serine protease TMPRSS2. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 12552–12561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Schroeder, S.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Muller, M.A.; Drosten, C.; Pohlmann, S. Nafamostat mesylate blocks activation of SARS-CoV-2: New treatment option for COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Matsuyama, S.; Li, X.; Takeda, M.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Inoue, J.; Matsuda, Z. Identification of Nafamostat as a Potent Inhibitor of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus S Protein-Mediated Membrane Fusion Using the Split-Protein-Based Cell-Cell Fusion Assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6532–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.C.; Doyle, P.S.; Hsieh, I.; McKerrow, J.H. Cysteine protease inhibitors cure an experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Exp. Med. 1998, 188, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Vedantham, P.; Lu, K.; Agudelo, J.; Carrion, R.; Nunneley, J.W.; Barnard, D.; Pohlmann, S.; McKerrow, J.H.; Renslo, A.R.; et al. Protease inhibitors targeting coronavirus and filovirus entry. Antivir. Res. 2015, 116, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.Y.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.B.; Li, P.; Mi, D.; Ren, L.L.; Guo, L.; Guo, R.X.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.X.; et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Pan, T.; Zhang, J.S.; Li, Q.W.; Zhang, X.; Bai, C.; Huang, F.; Peng, T.; Zhang, J.H.; Liu, C.; et al. Glycopeptide Antibiotics Potently Inhibit Cathepsin L in the Late Endosome/Lysosome and Block the Entry of Ebola Virus, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV). J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 9218–9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Yu, F.; Liu, J.; Zou, F.; Pan, T.; Zhang, H. Teicoplanin potently blocks the cell entry of 2019-nCoV. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Lin, K.; Strick, N.; Neurath, A.R. Hiv-1 Inhibition by a Peptide. Nature 1993, 365, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddart, C.A.; Nault, G.; Galkina, S.A.; Thibaudeau, K.; Bakis, P.; Bousquet-Gagnon, N.; Robitaille, M.; Bellomo, M.; Paradis, V.; Liscourt, P.; et al. Albumin-conjugated C34 Peptide HIV-1 Fusion Inhibitor: Equipotent to C34 and T-20 in Vitro With Sustained Activity in SCID-hu Thy/Liv Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 34045–34052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, L.; Qi, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, S. Novel Recombinant Engineered gp41 N-terminal Heptad Repeat Trimers and Their Potential as Anti-HIV-1 Therapeutics or Microbicides. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25506–25515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shi, W.; Chappell, J.D.; Joyce, M.G.; Zhang, Y.; Kanekiyo, M.; Becker, M.M.; van Doremalen, N.; Fischer, R.; Wang, N.; et al. Importance of Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibodies Targeting Multiple Antigenic Sites on the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Glycoprotein To Avoid Neutralization Escape. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e02002–e02017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, S.; Hara, Y.; Kanoh, S.; Shinoda, M.; Kawano, S.; Fujikura, Y.; Kawana, A.; Shinkai, M. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia caused by camostat mesilate: The first case report. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2016, 19, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, T.; Balcom, J.H.; Antoniu, B.A.; Lewandrowski, K.; Warshaw, A.L.; Fernandez-del Castillo, C.F. Regional effects of nafamostat, a novel potent protease and complement inhibitor, on severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery 2001, 130, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosgerau, K.; Hoffmann, T. Peptide therapeutics: Current status and future directions. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.Y.; Kilby, J.M.; Saag, M.S. Enfuvirtide. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2002, 11, 1837–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Rasquinha, G.; Du, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, W.; Li, W.; Lu, L.; Jiang, S. A Peptide-Based HIV-1 Fusion Inhibitor with Two Tail-Anchors and Palmitic Acid Exhibits Substantially Improved In Vitro and Ex Vivo Anti-HIV-1 Activity and Prolonged In Vivo Half-Life. Molecules 2019, 24, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).