Abstract

Leveraging the immune system to thwart cancer is not a novel strategy and has been explored via cancer vaccines and use of immunomodulators like interferons. However, it was not until the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors that we realized the true potential of immunotherapy in combating cancer. Oncolytic viruses are one such immunotherapeutic tool that is currently being explored in cancer therapeutics. We present the most comprehensive systematic review of all oncolytic viruses in Phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials published to date. We performed a systematic review of all published clinical trials indexed in PubMed that utilized oncolytic viruses. Trials were reviewed for type of oncolytic virus used, method of administration, study design, disease type, primary outcome, and relevant adverse effects. A total of 120 trials were found; 86 trials were available for our review. Included were 60 phase I trials, five phase I/II combination trials, 19 phase II trials, and two phase III clinical trials. Oncolytic viruses are feverously being evaluated in oncology with over 30 different types of oncolytic viruses being explored either as a single agent or in combination with other antitumor agents. To date, only one oncolytic virus therapy has received an FDA approval but advances in bioengineering techniques and our understanding of immunomodulation to heighten oncolytic virus replication and improve tumor kill raises optimism for its future drug development.

1. Introduction

Enhancing the body’s own response to malignant cells through immune stimulation has been a vigorous focus of recent cancer research. Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are one such tool. These viruses are naturally occurring or can be modified to selectively infect and destroy cancer cells. In addition, there is evidence OVs can stimulate the host’s immune response to combat tumors [1]. Multiple viruses are currently under investigation including herpesvirus, adenovirus, poxvirus, picornavirus, and reovirus as possible oncolytic treatments. In 2015 talimogene herparepvec was the first OV approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for human use in the USA [2] and there are a number of other OVs currently in phase III testing. Here we discuss how OVs have been adapted to destroy cancer cells and summarize the clinical data on OVs currently under investigation.

2. Methods

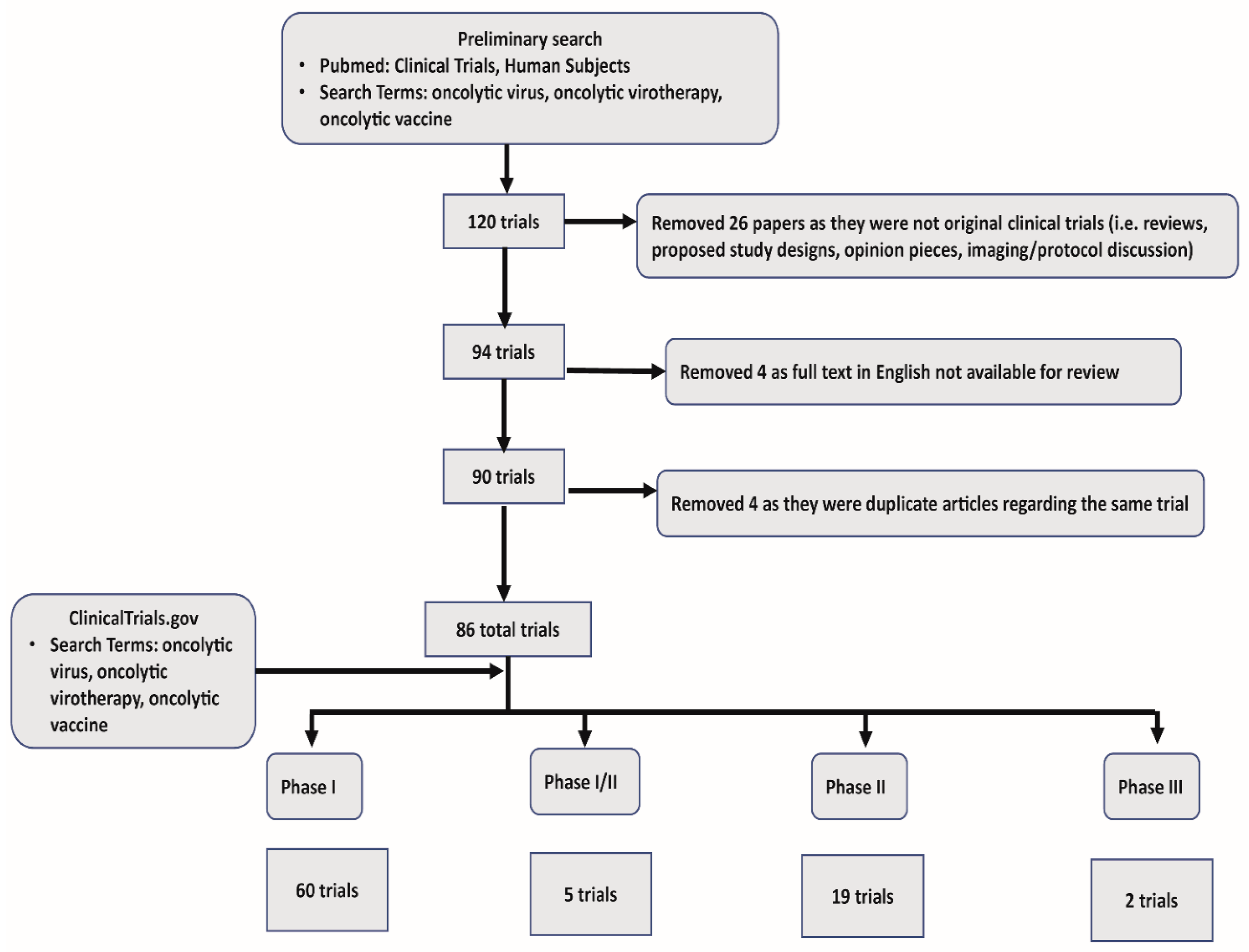

In our systematic review we collected all published clinical trials that utilized oncolytic viruses. Using Pubmed, we first narrowed our search to include “Clinical Trials” and “Humans.” Subsequent search criteria included “oncolytic virus”, “oncolytic virotherapy”, “oncolytic immunotherapy”, and “oncolytic vaccine”. Our initial search returned 120 articles. This preliminary search also captured reviews, proposed study protocols, and opinion pieces, which were excluded (26 in total). Papers not available in full text for review, or with no available English translation were excluded (4). Last, we found a limited number of articles that described different facets of the same trial, and these redundant articles were excluded (4). One unpublished study was identified in clinicaltrials.gov. In summary, we used 86 total trials, including 60 phase I, 5 phase I/II, 19 phase II, and 2 phase III trials for our review. See Figure 1 for a schematic representation of systematic review of OV clinical trial data and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Systematic review schematics.

3. Mechanism of Action

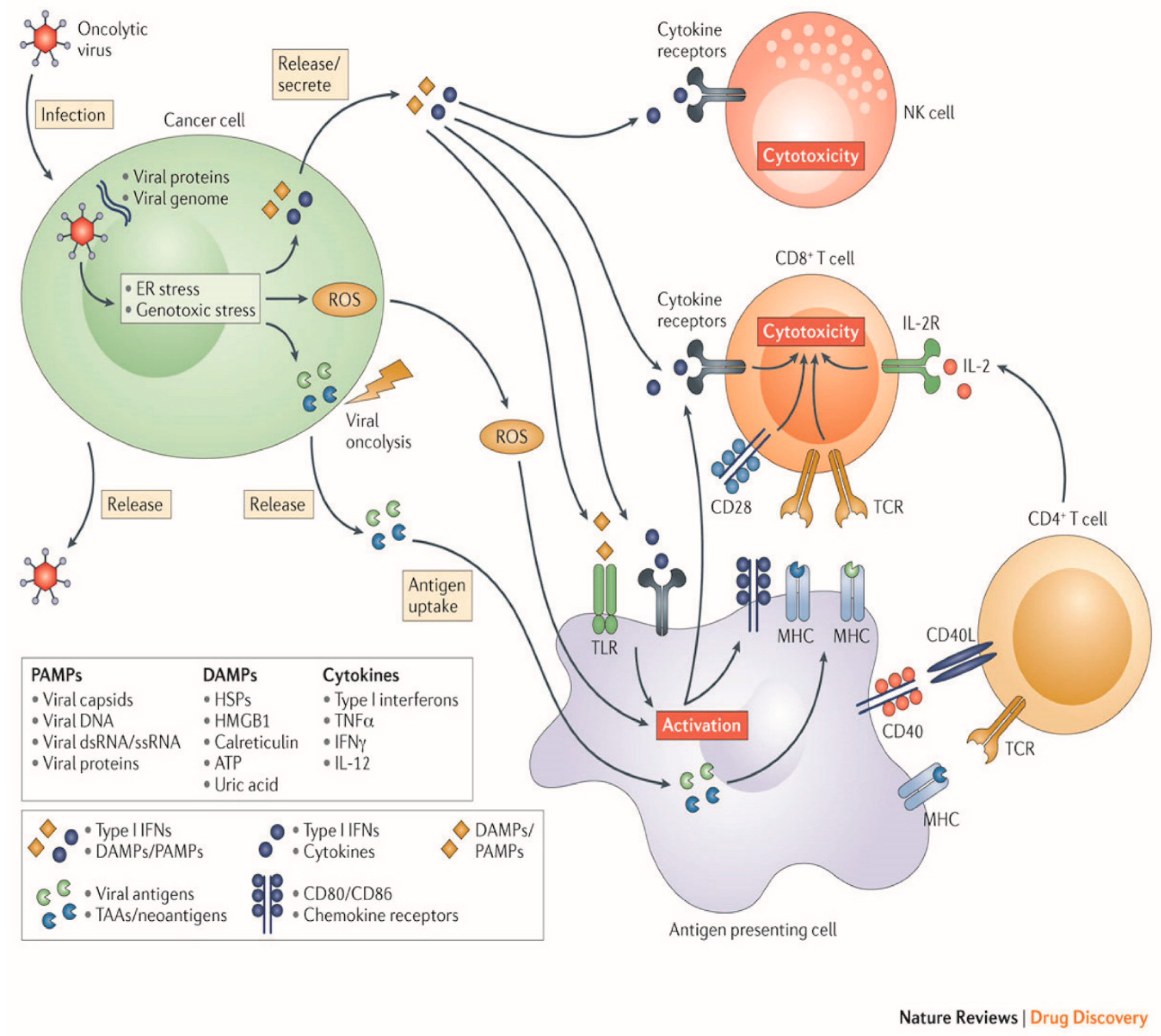

OV therapy relies on a two-part process of selectively infecting tumor cells, and then inducing antitumor activity through release of tumor antigens and immune stimulation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms employed by oncolytic viruses. (Original image used with permission from Springer Nature: Kaufman, H., Kohlhapp, F. & Zloza, A. Oncolytic viruses: A new class of immunotherapy drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 14: 642–662 2015).

4. Targeting Cancer Cells

OVs can target and destroy cancer cells by taking advantage of a tumor’s unique cellular activity. Strategies for infection and destruction of the tumor cells vary among OVs. Cancer cells can have altered or entirely absent signaling pathways that normal tissues use to defend against viral infection.

As an example, protein kinase receptor (PKR) and its associated interferon (IFN) pathway is integral to viral clearance, but is often underexpressed in certain cancers; low IFN expression renders the cancer cells susceptible to viral attack [3]. Another mechanism centers on the increased metabolic activity of tumor cells and rapid replication; for virally infected tumor cells this leads to increased viral replication and rate of lysis compared to normal tissue [4]. This situation enhances viral activity to destroy tumor cells.

Naturally occurring viruses already contain many strategies for evading host immunity and can take advantage of decreased defenses to target cancer cells. These cells often overexpress receptors or other proteins that the viruses already use you gain entry to normal cells. HSV-1 variants use nectins and herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM), expressed on cancer cell membranes, to gain entry. Some melanomas and carcinomas have increased expression of nectins and HVEM [5]. Measles virus utilize the CD46 receptor, which is often overexpressed in certain cancers [6].

Other OV’s are enhanced viruses that have been tailored to increase their affinity for malignant tissues. They are engineered to target proteins overexpressed in cancer cells. One such example is thymidine kinase (TK). A strain of HSV has been modified to favor tumor cells due to their high TK expression [7]. TK is an enzyme used for DNA synthesis and repair during cell replication, is therefore highly expressed on tumor cells. This engineered variant of HSV holds a TK-knock out. The knockout of TK results in preferential infection and destruction of cancerous tissues.

5. Direct Tumor Cell Lysis

After target infection of the tumor cell occurs, lysis of the tumor cell leads to the release of viral particles, cytokines, and other cellular contents, and a secondary response to this lysis ensues. Within this system, there is direct killing of surrounding cells by the release of these cytotoxic elements, which include granzymes and perforins. The cellular contents ATP, uric acid, and heat shock protein are known as danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which cause local inflammation. DAMPs and cytokines attract natural killer (NK) cells to the surrounding tissue. In addition, viral particles have protein sequences that can stimulate the immune system, known as pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).

OVs can also be engineered to deliver suicide genes to enhance direct tumor cell lysis. These genes encode enzymes that can convert prodrug into an active form to destroy tumor cells. ProstAtak (aglatimagene besadenovec) is an OV engineered to express HSV TK in infected cells; after injection, valcyclovir is administered that halts DNA replication in the tumor cell.

6. Antitumor Activity

OV antitumor activity depends on both direct malignant cell destruction as well as a stimulating systemic antitumor immunity. This immunity is induced when an infected cell is lysed. The viral antigens and cellular components are liberated into the cancer microenvironment. Release of DAMPs, PAMPs, and cytokines lead to maturation of antigen presenting cells (APCs), including the dendritic cells (DC). By these processes, tumor cells that had previously evaded the immune system can now be recognized and targeted by the immune system; destruction pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on immune cells are stimulated to recognize these PAMPs and DAMPs. PRRs specific to dendritic cells (DC)s within tumors can be directly stimulated by OV infection [8]. The subsequent activation of APCs then recruit CD4+ and CD8+ cells to destroy cells expressing viral antigens on tumors. One such example, in the activation antiviral CD8 T cells by reovirus lead to tumor regression [9]. This recognition of tumor antigens by the immune system is key to tumor destruction at distant sites that were not infected with the OV [10].

HSV and reovirus can prime antitumor immunity by stimulating T cell activity to destroy neighboring tumor cells [11,12]. Another genetically modified variant of HSV, Talimogene herparepvec (T-vec), has the GM-CSF cistron inserted into its genome. This modification enables high production and release of GM-CSF when the tumor cells are destroyed, resulting in enhanced DC recruitment and antigen presentation [13].

In addition to targeting the malignant cells themselves, OVs can destroy tumor vasculature. Some OVs are engineered to target angiogenesis, and other viruses inherently target the destruction of tumor vasculature. HSV and vaccinia viruses are one such example. These viruses depend on high expression of fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for replication to target new tumor vessels [14,15]. The vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) has been shown to infect blood vessels surrounding a tumor and cause thrombosis of its vessels [16].

7. Novel Trends in OV Advancements

Much of the emerging research for OVs focuses on how to amplify their immunogenicity and tumor destruction through insertion or exchange of human genes. These genes can improve cancer cell destruction through improved entry into cells, direct destruction of cancer cells, or recruitment of the patient’s immune system. These emerging viruses are particularly focused on recruitment of the host’s immune system to destroy the tumor.

One such virus in an ongoing phase 1 clinical trial utilizes a strain of HSV-1 to target glioblastomas (NCT02062827) [17]. This OV was modified to express IL-12, which improves the OV’s efficacy in destroying tumor cells and in the surrounding microenvironment. The release of IL-12 with tumor lysis leads to recruitment of dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages to the area for increased tumor destruction. The release IL-12 also exhibits an anti-angiogenic effect, which slows the growth of blood vessels for the tumor and decreases tumor growth.

TILT-123 is another exciting example of an OV equipped with proteins to enhance its anti-tumor activity. TILT-123 is an adenovirus engineered to express TNF-alpha and IL2 (NCT04217473) [18]. While infection with the OV can lead to tumor destruction as previously discussed, the addition of IL2 and TNF-alpha increases the immunogenicity of the therapy. Expression of TNF-alpha and IL-2 attracts T cells to the tumor and also enhances their infiltration into the cancer cells [19]. NCT04217473 is the first clinical trial to evaluate the safety of TILT-123′s in patients with advanced melanoma, enrolling patients in early 2020.

In addition to studies currently underway combining OVs with simultaneous checkpoint inhibitor therapy administration, viruses are being engineered to produce the antibodies themselves. An HSV-1 virus has recently been developed for use in glioblastoma therapy, which can express PD-1 antibodies [20]. While this construct has only been tested in murine models as of now, it is a promising example of enhancing OV tumor activity through gene insertion.

8. Augmentation of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. “Making Cold Tumors Hot: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–OV Combination Therapy Trials”

Remarkable progress has been made in the development of immunotherapy to treat cancers in the last decade. One type of immunotherapy is immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICBs), which are monoclonal antibodies that block receptor-ligand interactions that negatively regulate both innate and adaptive immunity. Prominent examples of ICBs include those that target cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) [21]. To date, multiple ICBs have been approved by the FDA to treat cancers; for example, ipilimumab (blocks CTLA-4), nivolumab (blocks PD-1), and pembrolizumab (blocks PD-1).

Combination therapies that use ICBs and oncolytic viruses are attractive. The oncolytic virus can recruit tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes into immune-deficient tumors and trigger the release of soluble tumor antigens, danger signals, and proinflammatory cytokines, which further increase T cell recruitment and promote immune cell activation [10,22]. Viral infection also increases the expression of CTLA-4, PD-1, and other immune checkpoint molecules, which would usually block T cell activation (and therefore antitumor immunity) but also sensitizes tumors to ICBs [23,24]. Non-clinical studies using B16–F10 melanoma demonstrated that localized injection of tumors with oncolytic Newcastle disease virus induced infiltration of tumor-specific CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells into both the injected tumor and distant tumors; this action increased the sensitivity of the tumors to systemic CTLA-4 blockade [10]. In another non-clinical model of triple-negative breast cancer, an oncolytic Maraba virus had activity as a neoadjuvant therapeutic, and it sensitized otherwise refractory tumors to ICB [25]. Other oncolytic viruses, such as B18R-deficient vaccinia virus [26] and vesicular stomatitis virus, express a library of melanoma antigens [27] and also showed significant (p < 0.05) therapeutic benefit in combination with ICB.

There is a strong mechanistic rationale for using combination oncolytic virus and ICBs since immune activation in the tumor environment as well as neo antigen production from oncolytic virus can improve efficacy of ICBs.

Ribas et al. confirmed that OV can potentially improve efficacy of anti PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. They evaluated safety and efficacy of combination T- VEC (talimogene laherparepvec) and pembrolizumab in a Phase 1b melanoma clinical trial (n = 21) and confirmed 62% objective response rate. The investigators found that OV can favorably alter tumor microenvironment (elevated CD8+ T cells, upregulation of INF-gamma, and increased expression of PD-L1 protein) resulted in improved response to the immune checkpoint inhibitor [28].

Improved efficacy was shown in Phase 2 clinical trial of combination oncolytic virus and CTLA-4 targeting ICBs [29]. Chesney et al. evaluated the combination T-VEC and Ipilimumab in a randomized phase II melanoma study (N = 198). 39 % patients had objective responses in the combination T-VEC/Ipilimumab arm while only 18% objective response was observed in the single agent ipilimumab arm (95% CI, P = 0.002). Of note, the responses were seen in injected lesions but also reported in distant visceral lesions in 52 % patients in the combination arm vs. only 23 % in the single agent ipilimumab arm.

A novel oncolytic virus called Coxsackievirus A21 (CAVATAK) shows synergy when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors [30]. The CAVATAK virus makes entry to cancer cells via ICAM1, which is often abundant on tumors. A clinical trial evaluating cavatak virus in combination with ipilimumab showed 50% objective responses in melanoma patients. Similarly, a trial evaluating combination cavatak virus with pembrolizumab in advance solid tumors reveled no dose limiting toxicities (DLT) [31]. A phase 1b Keynote 200 clinical trial of combination cavatak + pembrolizumab in advance non-small cell lung cancer and bladder cancer confirmed no DLT; 12.8% grade 3 treatment-related adverse events were noted, however no grade 4 or 5 toxicities were seen [32,33]. Table 1 summarizes combination immune checkpoint and oncolytic virus clinical trials.

Table 1.

Summary of combination oncolytic virus and immune checkpoint inhibitor (ici) clinical trials.

9. Modes of OV Delivery

Depending on both the OV and cancer, virus administration can be delivered using a systemic or more targeted approach.

9.1. Intralesional Route

A locoregional approach has been used for melanoma, prostate, and gliomas. Intradermal injections of T-vec is employed for melanoma, intracavitary injection for gliomas, and intraperitoneal injection for treatment of ovarian cancer are a few examples. Depending on the location and accessibility of the tumors the virus can be delivered once (i.e., to a glioma cavity during surgery) or rely on repeated injections such as in melanoma [35]. The efficacy of intratumoral injection can extend beyond the lesions injected. Studies report evidence of tumor lysis in satellite lesions not injected with virus [36]. OV delivery can also employ intravenous (IV) release, through either peripheral IV injection, or more targeted, through hepatic artery infusion for liver metastasis [37].

Intralesional injection can be limited by the extracellular matrix that surrounds otherwise accessible tumors. In desmoplastic tissues, the spread of the virus can be limited by excessive fibrin and connective tissues [38]. Agents such as bacterial collagenase have been used to increase the spread OV injection for local tumors such as melanoma, which demonstrated some efficacy [39]. However, collagenase cannot be used systemically, which limits its application. One of many systemic agents under investigation includes the antihypertensive agent losartan, which reportedly decreased collagen deposition, increased blood flow as well as uptake of the cytotoxic agent in pancreatic cancer [40].

Vascular injection also has limitations. Tumor vasculature is markedly disorganized and more unstable than normal vessels [41]; this property makes vascular injections less reliable for downstream delivery of the virus to surrounding cancer cells. However, currently there are several avenues under investigation to stabilize these tissues and enhance delivery of cancer immunotherapy; some examples include the use of nitric oxide [42] and VEGF [43].

9.2. Intravenous Route

Intra lesional OV administration is currently by far the most commonly used delivery method. However many trials are also evaluating intravenous route of administration [44,45] due to its inherent advantages. Some of the advantages of IV route includes ease of administration, standardization of administered drug dose, potential for multiple and long term administration, and wider application of IV based treatment especially in smaller community clinics [46]. The key detriment to IV administration so far has been development of neutralizing antibodies and clearance of OV [47,48,49]. There are at least eight clinical studies that we can confirm which used IV route for OV administration.

10. Phase I Trials

In our systematic review we have summarized 59 phase I trials investigating 36 OVs. Phase I trials seek to demonstrate safety and dosing. Of those 36 viruses, many did not proceed past this initial phase of investigation, or were altered in some way to improve efficacy. It is not feasible to summarize all Phase I trials here, but a summary of all reviewed trials can be found in Table 2 Here we discuss a few OVs of interest, many of which show promise and have progressed to Phase II investigations.

Table 2.

Summary of oncolytic virus use in phase I clinical trials.

11. Pexa-Vec

Pexa-Vec/JX-594, or pexastimogene devacirepvec, is an oncolytic pox virus that has been studied across a variety of malignancies, including melanoma, colorectal cancer, and liver metastases. This vaccinia virus was altered for oncolytic activity by deactivation of its thymidine kinase, with the addition of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The GM-CSF is added to increase oncolysis and induce adaptive immune response to the tumor cells [107]. A majority of the studies focused on liver cancers, either HCC or metastases to liver. In one study, 14 patients received intratumoral injections of the virus. Grade III hyperbilirubinemia was observed with the highest dosed group, and 4 patients experienced transient thrombocytopenia, as high as grade 3. Under RECIST criteria, 3 patients had a partial response (PR) and 6 had stable disease (SD). Interestingly, a response could be seen not only in the tumors that had been injected, but also in the satellite lesions [108]. Pexa-vec has also been studied using IV administration. In a study of 15 patients with colorectal cancer, IV infusion of Pexa-vec resulted in SD in 67% of patients [94]. Pexa-vec showed promise in phase II clinical trials (see Table 3), but the Phase III trial that combined Pexa-vec with sorafenib in patients with metastatic HCC (Clinical Trial: NCT02562755) was terminated in august 2019 due to lack of effectiveness.

Table 3.

Summary of oncolytic virus use in phase II clinical trials.

12. Ad5/3 delta 24 (CRAd)

Ad5/3 delta 24 is an oncolytic adenovirus being studied for application across a number of malignancies, and prominently with gynecologic cancers. The virus gains entry into cells by binding to the Ad3 receptor, which has increased expression on tumor cells. Delta-24 signifies a 24 base pair deletion in the E1a gene, leading to preferential replication in cells with defective retinoblastoma (Rb) expression, a common occurrence in tumor cells. Twenty-one patients with gynecologic malignancies received intraperitoneal injection of the OV. The treatment was well tolerated with only grade 1–2 adverse events (AE) of fatigue, malaise, and abdominal pain. The study reported that 67% achieved SD, with the remainder progressing after 1 month [72].

Ad5/3 delta 24 has been further manipulated with the addition GM-CSF gene to stimulate immune activity, with strains such as CGTG-102 and CGTG-602. In a study of CGTG-102, 60 patients with advanced solid tumors received either single of multiple dose intratumoral injections of the OV. Stable disease or better was reached in 51% of patients who received serial injections (vs. 41% in single injection). AE were minimal and limited to grade 1–2 flu-like symptoms.

13. Seneca Valley Virus

Seneca Valley Virus (SVV) is a more recent addition into OV group therapy. Its application focuses on tumors with neuroendocrine features, and has also proven safe in treatment of pediatric tumors [102]. In a study of 22 pediatric patients with neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and rare tumors with NET features, NTX-010, a SVV strain, was studied alone and in combination with cyclophosphamide. Adverse events included leukopenia, neutropenia, and tumor pain, but only 1 grade 3 toxicity (tumor pain) was reported. In another trial of SVV, SVV-001, 30 patients with advanced solid tumors with neuroendocrine features received IV injections of the OV. One patient with SCLC was progression free for 10 months [103]. This is a promising finding that warrants future study with neuroendocrine malignancies. However, a phase 2 study evaluating the efficacy of SVV in extensive stage small cell carcinoma was unfortunately negative. Non-progressive patients post 4 cycles of platinum doublet were randomized 1:1 to receive single IV infusion of SVV vs placebo. This trial was terminated due to futility as no improvement in median PFS was seen at interim analysis [127].

Recently a novel biomarker called tumor endothelial marker 8 (TEM 8) has been confirmed to act as a receptor for SVV, facilitating in viral entry in tumor cells. TEM 8 pre-screening can potentially form an important strategy to select patients for SVV therapeutic clinical trials [128].

14. Polio Virus

PVSRIPO is an oncolytic polio virus that has demonstrated promising results in the treatment of glioblastoma. It is engineered to target CD155/Necl5, the onco-fetal adhesion protein found in many solid tumors. In a study of 61 patients, the virus was injected intratumorally (Desjardins 2018) [69]. AE were minimal, with grade 4 intracranial hemorrhage occurring at only the highest injection dose. Survival is higher as compared to historical controls. Studies are underway to determine the safety of the therapy in pediatric glioma (NCT03043391) as well as invasive breast cancer (NCT03564782). It is also being studied in combination with immunotherapy for melanoma, including nivolumab (NCT04125719) and Atezolizumab (NCT03973879)

15. MV-NIS

MV-NIS is a unique oncolytic virus, composed of an Edmonston strain of measles virus which has been altered to express a sodium iodide transporter. Measles virus can target tumor cells through the CD46 antigen. Additionally, infection of tumor cells by the virus can be monitored through administration of Iodine-123 via SPECT imaging.

MV-NIS has been studied in the treatment of myeloma, and has exhibited promising results. In a study of 29 patients 1 CR was reported (Dispenzieri 2017) [100]. There were also some cases of decreased circulating free light chains, but they did increase once the patient cleared the virus.

16. Phase II Trials

Those viruses that were safe and had early clinical evidence of success progressed to Phase II studies. Phase II investigations seek to demonstrate clinical efficacy. Thirteen viruses across 24 trials were available for review. The review of Phase II data also included 6 Phase I/II trials. Again, because of limitation of space, we will discuss a few OVs used across a variety of cancers. A complete table of Phase I/II and Phase II trials in our review can be found in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively.

Table 4.

Summary of oncolytic virus use in Phase I/II studies.

17. Reolysin

Reolysin (Pelareorep) is a strain of the reovirus type 3D that has been investigated in a variety of cancers, including ovarian, breast, melanoma, pancreatic, glioma, and multiple myeloma. Ten Phase I trials are in summarized in Table 2. This OV has provided particularly promising evidence, and use in Phase II trials have increased OS in multiple cancers. In one study of 74 patients with metastatic breast cancer, OS increased as compared to paclitaxel monotherapy (17·4 months vs. 10·4 months) [114]. In a smaller study of 14 patients with melanoma, the addition of Reolysin to paclitaxel and carboplatin saw a 21% ORR (3 patients) [111]. Reolysin in combination with gemcitabine was superior to gemcitabine monotherapy in a study of 34 patients with pancreatic cancer [113]; OS and 1- and 2-year survival was increased. Outcomes were similar to those undergoing FOLFIRINOX therapy, but the side effect profile was better tolerated with Reolysin+gemcitabine. The same success has yet to be demonstrated ovarian cancer. In a trial with 108 patients with ovarian, tubal or peritoneal cancer receiving paclitaxel, adding Reolysin did not improve outcomes [109].

18. ProstAtak

ProstAtak/aglatimagene besadenovec/Adv-tk is an adenovirus which has been modified to express HSV thymidine kinase. After infection of tumor cells with the virus, valcyclovir or ganciclovir is administered that subsequently induces cell death. As the name may suggest, this OV was engineered for application in prostate cancer, but has also been tested in other cancers including a Phase II trial with gliomas. In one study of 48 patients with malignant gliomas, AdV-tk was injected into the tumor cavity following resection, and subsequently received valcyclovir. Overall survival was extended in the treatment group, particularly in those patients that achieved total gross resection at time of surgery [118]. In studies that involve prostate cancer, one example included a study of 10 patients who received intraprostatic injection of Adv-tk as neoadjuvant therapy to surgery. PSA levels were monitored as a marker of tumor suppression. Eight of nine patients continued to have reduced PSA levels 10 years following injection.

19. ONYX-015

ONYX-015 (previously known as Ad2/5 dl1520) is an oncolytic adenovirus which was engineered to target p53-deficient cells. This adenovirus is deficient in a portion of the E1B gene that produces a 55 kDa protein. This protein typically binds to p53 to prevent apoptosis; in p53-deficient cells, the virus can replicate and lyse cancer cells. Phase II trials involved those for head and neck cancer as well as liver metastases of gastrointestinal cancers. Intratumoral injection of head and neck cancers demonstrated marked (> 50%) tumor regression in 14% of patients [135] It has also been studied in combination with 5-FU/cisplatin, for which there was 27% CR and 36% PR [119]. Hepatic artery infusion of the virus was used in 2 studies, either in combination with 5-FU/Leucovorin, or as a single agent in patients who had previously failed 5-FU/Leucovorin therapy. While there was evidence of biochemical response, increased interleukins and other immune stimulatory molecules, no clinical response was seen [37]. In the ONYX-15 single agent study [121] many patients were removed from the study due to concern about cancer progression seen on CT imaging. It was suggested alternate imaging, such as PET should be utilized in the future as this technology suggested that the increase in tumor size may have been inflammatory response from viral induced infection and inflammation.

20. Cavatak

Cavatak, otherwise known as CVA21, is a coxsackievirus which targets ICAM-1 to gain entry into tumor cells. Currently there is data available for studies investigating the virus’ use in advanced melanoma and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. In a phase I study of 15 patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, patients received intravesicular injection of the virus. No serious AE occurred, and 1 CR was reported. A phase II study examined 57 patients with intratumoral injection CVA21 with advanced melanoma. There was a 21% durable response rate (CR+PR).

There are a number of current trials investigating Cavatak, predominantly in combination with immunotherapy. Its safety for use in NSCLC, melanoma, bladder cancer, and prostate cancer is being studied in the STORM trial (NCT02043665), with an additional arm in the bladder cancer and NSCLC groups to be used in combination with pembrolizumab. The CAPRA study (NCT02565992) is also combining Cavatak with pembrolizumab in metastatic melanoma. The MITCI trial (NCT02307149) is combining intratumoral Cavatak with Ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma.

21. Phase 3 Trials

In our systematic review, available Phase III data were limited to 2 trials of talimogene herparepvec (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of oncolytic virus use in Phase III clinical trials.

22. Talimogene Herparepvec

Talimogene herparepvec (T-vec) is currently the only FDA approved OV [2] available in the US. T-vec is an HSV-1 virus, which expresses human GM-CSFT-vec, that can only replicate in cancer cells. This happens because of a dysfunctional PKR pathway in cancer cells. In normal cells, viral infection causes PKR activation, which in turn, leads to an inhibition of protein synthesis within the cell and ultimately decreased viral replication. In contrast, with a dysfunction RKP system in cancer cells, viral replication proceeds unhindered [138]. However, in cancerous cells allow replication by the virus.

T-vec is indicated for unresected advance stage melanoma, administered via intratumoral injection [2]. Phase 3 trials demonstrated mixed results [36,137]. The safety profile was consistent with previous trials, with flu-like symptoms and injection site pain reported; 7% of patients had grade 3 or higher AE including nausea, vomiting, fever and abdominal pain. In the OPTiM Phase III trial [36] tumors that were not injected also demonstrated regression, which indicated possible systemic efficacy. Despite this, OS was not increased. Other studies compared T-vec to simple GM-CSF injection; T-vec produced a higher DRR (durable response rate) and increased OS than did GM-CSF alone [136].

T-vec has also been studied in combination with immunotherapy in initial phase I studies [28,139]. T-vec was injected into lesions with systemic ipilimumab therapy. Combining these two agents is more effective that either treatment alone. In another investigation, combination with pembrolizumab demonstrated increased ORR as compared pembrolizumab alone [28].

There is a Phase III trial underway examining combination therapy of systemic pembrolizumab with intratumoral injection of T-vec (NCT02263508).

23. Limitations of OVs

Despite the exciting evidence presented in the previously mentioned trials, OV therapy has limitations. One challenge is delivering the virus to the targeted lesions. Intratumoral injection is limited to accessible tumors such as melanomas, or targeted hepatic artery injection for hepatic lesions. While IV administration would be ideal, it can lead to sequestration of virus in the liver, limiting whole body distribution [140] as well as development of neutralizing antibodies.

Neutralizing antibodies are one of the greatest barriers to OV efficacy. Viruses selected for oncolytic virotherapy are those that can infect human cells, which carries both benefits and drawbacks for treatment. Many humans have been previously exposed to or vaccinated against some of the naturally occurring viruses used in OV therapy, and subsequently possess neutralizing antibodies to the virus. Nearly 90% of humans have antibodies against reovirus [141]. The measles virus is in development as an OV, and its success is hindered by the patient’s circulating antibodies [142].

24. Conclusions

The success of immune checkpoint inhibitors has propelled the field of oncology towards exploring other immunotherapeutic mechanisms to abrogate cancer growth. Oncolytic viruses are one such promising avenue with the potential to advance oncology therapeutics. While there has been only one FDA approved anticancer agent to date, a multitude of the oncolytic virus in various stages of clinical development makes for a promising story yet to unfold. The biggest advantage we have in harnessing oncolytic viral therapy lies in our capability to bioengineer these nanomicrobes. With improved understanding of molecular pathophysiology, we have the potential to manipulate oncolytic viruses to match evolving cancer challenges.

Author Contributions

M.C.: literature search, data interpretation, and writing, A.C.: study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and editing of manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Mary Cook has no conflicts to report. Aman Chauhan has received research support from BMS, Clovis, Entrinsic Health Solution, EMD Serono, and Lexicon Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Lichty, B.D.; Breitbach, C.J.; Stojdl, D.F.; Bell, J.C. Going viral with cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amgen. FDA Approves IMLYGICTM (Talimogene Laherparepvic) as First Oncolytic Viral Therapy in the US. 2018. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fda-approves-imlygic-talimogene-laherparepvec-as-first-oncolytic-viral-therapy-in-the-us-300167270.html (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Clemens, M.J. Targets and mechanisms for the regulation of translation in malignant transformation. Oncogene 2004, 23, 3180–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghi, M.; Visted, T.; Depinho, R.A.; Chiocca, E.A. Oncolytic herpes virus with defective ICP6 specifically replicates in quiescent cells with homozygous genetic mutations in p16. Oncogene 2008, 27, 4249–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Chan, M.K.; Pornchai, O.; Eisenberg, D.P.; Shah, J.P.; Singh, B.; Fong, Y.; Wong, R.J. Enhanced nectin-1 expression and herpes oncolytic sensitivity in highly migratory and invasive carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 4889–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.D.; Nakamura, T.; Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W. High CD46 receptor density determines preferential killing of tumor cells by oncolytic measles virus. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 4919–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martuza, R.L.; Malick, A.; Markert, J.M.; Ruffner, K.L.; Coen, D.M. Experimental therapy of human glioma by means of a genetically engineered virus mutant. Science 1991, 252, 854–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errington, F.; Steele, L.; Prestwich, R.; Harrington, K.J.; Pandha, H.S.; Vidal, L.; de Bono, J.; Selby, P.; Coffey, M.; Vile, R.; et al. Reovirus activates human dendritic cells to promote innate antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 6018–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, P.T.; Boudreau, J.E.; Stephenson, K.; Wan, Y.; Lichty, B.D.; Mossman, K.L. Adaptive antiviral immunity is a determinant of the therapeutic success of oncolytic virotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarin, D.; Holmgaard, R.B.; Subudhi, S.K.; Park, J.S.; Mansour, M.; Palese, P.; Merghoub, T.; Wolchok, J.D.; Allison, J.P. Localized oncolytic virotherapy overcomes systemic tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 226ra32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestwich, R.J.; Errington, F.; Ilett, E.J.; Morgan, R.S.; Scott, K.J.; Kottke, T.; Thompson, J.; Morrison, E.E.; Harrington, K.J.; Pandha, H.S.; et al. Tumor infection by oncolytic reovirus primes adaptive antitumor immunity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 7358–7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, M.; Rabkin, S.D.; Kojima, H.; Martuza, R.L. Herpes simplex virus as an in situ cancer vaccine for the induction of specific anti-tumor immunity. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conry, R.M.; Westbrook, B.; McKee, S.; Norwood, T.G. Talimogene laherparepvec: First in class oncolytic virotherapy. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2018, 14, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbach, C.J.; Arulanandam, R.; De Silva, N.; Thorne, S.H.; Patt, R.; Daneshmand, M.; Moon, A.; Ilkow, C.; Burke, J.; Hwang, T.H.; et al. Oncolytic vaccinia virus disrupts tumor-associated vasculature in humans. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benencia, F.; Courreges, M.C.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Buckanovich, R.J.; Zhang, L.; Carroll, R.H.; Morgan, M.A.; Coukos, G. Oncolytic HSV exerts direct antiangiogenic activity in ovarian carcinoma. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005, 16, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbach, C.J.; De Silva, N.S.; Falls, T.J.; Aladl, U.; Evgin, L.; Paterson, J.; Sun, Y.Y.; Roy, D.G.; Rintoul, J.L.; Daneshmand, M.; et al. Targeting tumor vasculature with an oncolytic virus. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Phase 1 Study of M032 (NSC 733972), a Genetically Engineered HSV-1 Expressing IL-12, in Patients with Recurrent/Progressive Glioblastoma Multiforme, Anaplastic Astrocytoma, or Gliosarcoma. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02062827 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- A Phase 1, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation Clinical Trial of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha and Interleukin 2 Coding Oncolytic Adenovirus TILT-123 in Melanoma Patients Receiving Adoptive Cell Therapy with Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04217473 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Havunen, R.; Siurala, M.; Sorsa, S.; Gronberg-Vaha-Koskela, S.; Behr, M.; Tahtinen, S.; Santos, J.M.; Karell, P.; Rusanen, J.; Nettelbeck, D.M.; et al. Oncolytic Adenoviruses Armed with Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha and Interleukin-2 Enable Successful Adoptive Cell Therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2017, 4, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, C.; Alayo, Q.; De Laura, I.; McNulty, J.; Grauwet, K.; Ito, H.; Bhaskaran, V.; Mineo, M.; Lawler, S.E.; Shah, K.; et al. Arming an Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 with a Single-chain Fragment Variable Antibody against PD-1 for Experimental Glioblastoma Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyi, C.; Postow, M.A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in solid tumors: Opportunities and challenges. Immunotherapy 2016, 8, 821–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajani, K.R.; Vile, R.G. Harnessing the Power of Onco-Immunotherapy with Checkpoint Inhibitors. Viruses 2015, 7, 5889–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ravindranathan, R.; Kalinski, P.; Guo, Z.S.; Bartlett, D.L. Rational combination of oncolytic vaccinia virus and PD-L1 blockade works synergistically to enhance therapeutic efficacy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intlekofer, A.M.; Thompson, C.B. At the bench: Preclinical rationale for CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade as cancer immunotherapy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois-Daigneault, M.C.; Roy, D.G.; Aitken, A.S.; El Sayes, N.; Martin, N.T.; Varette, O.; Falls, T.; St-Germain, L.E.; Pelin, A.; Lichty, B.D.; et al. Neoadjuvant oncolytic virotherapy before surgery sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer to immune checkpoint therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaao1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinpeter, P.; Fend, L.; Thioudellet, C.; Geist, M.; Sfrontato, N.; Koerper, V.; Fahrner, C.; Schmitt, D.; Gantzer, M.; Remy-Ziller, C.; et al. Vectorization in an oncolytic vaccinia virus of an antibody, a Fab and a scFv against programmed cell death -1 (PD-1) allows their intratumoral delivery and an improved tumor-growth inhibition. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1220467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilett, E.; Kottke, T.; Thompson, J.; Rajani, K.; Zaidi, S.; Evgin, L.; Coffey, M.; Ralph, C.; Diaz, R.; Pandha, H.; et al. Prime-boost using separate oncolytic viruses in combination with checkpoint blockade improves anti-tumour therapy. Gene Ther. 2017, 24, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, A.; Dummer, R.; Puzanov, I.; VanderWalde, A.; Andtbacka, R.H.I.; Michielin, O.; Olszanski, A.J.; Malvehy, J.; Cebon, J.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Oncolytic Virotherapy Promotes Intratumoral T Cell Infiltration and Improves Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 170, 1109–1119.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, J.; Puzanov, I.; Collichio, F.; Singh, P.; Milhem, M.M.; Glaspy, J.; Hamid, O.; Ross, M.; Friedlander, P.; Garbe, C.; et al. Randomized, Open-Label Phase II Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination with Ipilimumab Versus Ipilimumab Alone in Patients with Advanced, Unresectable Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1658–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxsackievirus A21 Synergizes with Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, OF9. [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pandha, H.; Harrington, K.; Ralph, C.; Melcher, A.; Gupta, S.; Akerley, W.; Sandborn, R.E.; Rudin, C.; Rosenberg, J.; Kaufman, D.; et al. Abstract CT115: Phase 1b KEYNOTE 200 (STORM study): A study of an intravenously delivered oncolytic virus, Coxsackievirus A21 in combination with pembrolizumab in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2017, 77 (Suppl. 13), CT115. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, C.M.; Pandha, H.S.; Gupta, S.; Zibelman, M.R.; Akerley, W.; Day, D.; Hill, A.G.; Sanborn, R.E.; O’Day, S.J.; Clay, T.D.; et al. LBA40—Phase Ib KEYNOTE-200: A study of an intravenously delivered oncolytic virus, coxsackievirus A21 in combination with pembrolizumab in advanced NSCLC and bladder cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, viii732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Phase 1, Dose-finding and Signal-seeking Study of the Safety & Efficacy of Intravenous CAVATAK® Alone and in Combination with Pembrolizumab in Patients with Late Stage Solid Tumours (VLA-009 STORM/KEYNOTE-200). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02043665 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Kelly, C.M.; Antonescu, C.R.; Bowler, T.; Munhoz, R.; Chi, P.; Dickson, M.A.; Gounder, M.M.; Keohan, M.L.; Movva, S.; Dholakia, R.; et al. Objective Response Rate Among Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Sarcoma Treated with Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination with Pembrolizumab: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senzer, N.N.; Kaufman, H.L.; Amatruda, T.; Nemunaitis, M.; Reid, T.; Daniels, G.; Gonzalez, R.; Glaspy, J.; Whitman, E.; Harrington, K.; et al. Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 5763–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andtbacka, R.H.; Agarwala, S.S.; Ollila, D.W.; Hallmeyer, S.; Milhem, M.; Amatruda, T.; Nemunaitis, J.J.; Harrington, K.J.; Chen, L.; Shilkrut, M.; et al. Cutaneous head and neck melanoma in OPTiM, a randomized phase 3 trial of talimogene laherparepvec versus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for the treatment of unresected stage IIIB/IIIC/IV melanoma. Head Neck 2016, 38, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, T.; Galanis, E.; Abbruzzese, J.; Sze, D.; Wein, L.M.; Andrews, J.; Randlev, B.; Heise, C.; Uprichard, M.; Hatfield, M.; et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of a replication-selective oncolytic adenovirus (dl1520): Phase II viral, immunologic, and clinical endpoints. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 6070–6079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Netti, P.A.; Berk, D.A.; Swartz, M.A.; Grodzinsky, A.J.; Jain, R.K. Role of extracellular matrix assembly in interstitial transport in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 2497–2503. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, T.D.; Grandi, P.; Mok, W.; Alexandrakis, G.; Insin, N.; Zimmer, J.P.; Bawendi, M.G.; Boucher, Y.; Breakefield, X.O.; Jain, R.K. Degradation of fibrillar collagen in a human melanoma xenograft improves the efficacy of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 2509–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Boucher, Y.; Liu, H.; Ferreira, D.; Hooker, J.; Catana, C.; Hoover, A.J.; Ritter, T.; Jain, R.K.; Guimaraes, A.R. Noninvasive Assessment of Losartan-Induced Increase in Functional Microvasculature and Drug Delivery in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 9, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yokoda, R.; Nagalo, B.M.; Vernon, B.; Oklu, R.; Albadawi, H.; DeLeon, T.T.; Zhou, Y.; Egan, J.B.; Duda, D.G.; Borad, M.J. Oncolytic virus delivery: From nano-pharmacodynamics to enhanced oncolytic effect. Oncolytic Virother. 2017, 6, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, D.; Kashiwagi, S.; Jain, R.K. The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Goel, S.; Duda, D.G.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Vascular normalization as an emerging strategy to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2943–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W. Oncolytic Virotherapy: A Contest between Apples and Oranges. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Suksanpaisan, L.; Naik, S.; Nace, R.; Federspiel, M.; Peng, K.W.; Russell, S.J. Reporter gene imaging identifies intratumoral infection voids as a critical barrier to systemic oncolytic virus efficacy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2014, 1, 14005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.; Carlisle, R. Achieving systemic delivery of oncolytic viruses. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbach, C.J.; Burke, J.; Jonker, D.; Stephenson, J.; Haas, A.R.; Chow, L.Q.; Nieva, J.; Hwang, T.H.; Moon, A.; Patt, R.; et al. Intravenous delivery of a multi-mechanistic cancer-targeted oncolytic poxvirus in humans. Nature 2011, 477, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evgin, L.; Acuna, S.A.; Tanese de Souza, C.; Marguerie, M.; Lemay, C.G.; Ilkow, C.S.; Findlay, C.S.; Falls, T.; Parato, K.A.; Hanwell, D.; et al. Complement inhibition prevents oncolytic vaccinia virus neutralization in immune humans and cynomolgus macaques. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, K.D.; Stallwood, Y.; Green, N.K.; Ulbrich, K.; Mautner, V.; Seymour, L.W. Polymer-coated adenovirus permits efficient retargeting and evades neutralising antibodies. Gene Ther. 2001, 8, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, A.T.; Ganly, I.; Soutar, D.S.; Brown, S.M. Potential for efficacy of the oncolytic Herpes simplex virus 1716 in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2008, 30, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streby, K.A.; Geller, J.I.; Currier, M.A.; Warren, P.S.; Racadio, J.M.; Towbin, A.J.; Vaughan, M.R.; Triplet, M.; Ott-Napier, K.; Dishman, D.J.; et al. Intratumoral Injection of HSV1716, an Oncolytic Herpes Virus, Is Safe and Shows Evidence of Immune Response and Viral Replication in Young Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.C.; Coffin, R.S.; Davis, C.J.; Graham, N.J.; Groves, N.; Guest, P.J.; Harrington, K.J.; James, N.D.; Love, C.A.; McNeish, I.; et al. A phase I study of OncoVEXGM-CSF, a second-generation oncolytic herpes simplex virus expressing granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6737–6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markert, J.M.; Razdan, S.N.; Kuo, H.C.; Cantor, A.; Knoll, A.; Karrasch, M.; Nabors, L.B.; Markiewicz, M.; Agee, B.S.; Coleman, J.M.; et al. A phase 1 trial of oncolytic HSV-1, G207, given in combination with radiation for recurrent GBM demonstrates safety and radiographic responses. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Y.; Kim, T.; Bhargava, A.; Schwartz, L.; Brown, K.; Brody, L.; Covey, A.; Karrasch, M.; Getrajdman, G.; Mescheder, A.; et al. A herpes oncolytic virus can be delivered via the vasculature to produce biologic changes in human colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voit, C.; Kron, M.; Schwurzer-Voit, M.; Sterry, W. Intradermal injection of Newcastle disease virus-modified autologous melanoma cell lysate and interleukin-2 for adjuvant treatment of melanoma patients with resectable stage III disease. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2003, 1, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecora, A.L.; Rizvi, N.; Cohen, G.I.; Meropol, N.J.; Sterman, D.; Marshall, J.L.; Goldberg, S.; Gross, P.; O’Neil, J.D.; Groene, W.S.; et al. Phase I trial of intravenous administration of PV701, an oncolytic virus, in patients with advanced solid cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 2251–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurie, S.A.; Bell, J.C.; Atkins, H.L.; Roach, J.; Bamat, M.K.; O’Neil, J.D.; Roberts, M.S.; Groene, W.S.; Lorence, R.M. A phase 1 clinical study of intravenous administration of PV701, an oncolytic virus, using two-step desensitization. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotte, S.J.; Lorence, R.M.; Hirte, H.W.; Polawski, S.R.; Bamat, M.K.; O’Neil, J.D.; Roberts, M.S.; Groene, W.S.; Major, P.P. An optimized clinical regimen for the oncolytic virus PV701. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulstone, V.; Khan, K.; Pandha, H.S.; Rudman, S.; Coffey, M.; Gill, G.M.; Melcher, A.A.; Vile, R.; Harrington, K.J.; de Bono, J.; et al. Phase I trial of cyclophosphamide as an immune modulator for optimizing oncolytic reovirus delivery to solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolkema, M.P.; Arkenau, H.T.; Harrington, K.; Roxburgh, P.; Morrison, R.; Roulstone, V.; Twigger, K.; Coffey, M.; Mettinger, K.; Gill, G.; et al. A phase I study of the combination of intravenous reovirus type 3 Dearing and gemcitabine in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, L.; Pandha, H.S.; Yap, T.A.; White, C.L.; Twigger, K.; Vile, R.G.; Melcher, A.; Coffey, M.; Harrington, K.J.; DeBono, J.S. A phase I study of intravenous oncolytic reovirus type 3 Dearing in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 7127–7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, P.; Roldan, G.; George, D.; Wallace, C.; Palmer, C.A.; Morris, D.; Cairncross, G.; Matthews, M.V.; Markert, J.; Gillespie, Y.; et al. A phase I trial of intratumoral administration of reovirus in patients with histologically confirmed recurrent malignant gliomas. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, K.J.; Karapanagiotou, E.M.; Roulstone, V.; Twigger, K.R.; White, C.L.; Vidal, L.; Beirne, D.; Prestwich, R.; Newbold, K.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Two-stage phase I dose-escalation study of intratumoral reovirus type 3 dearing and palliative radiotherapy in patients with advanced cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3067–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comins, C.; Spicer, J.; Protheroe, A.; Roulstone, V.; Twigger, K.; White, C.M.; Vile, R.; Melcher, A.; Coffey, M.C.; Mettinger, K.L.; et al. REO-10: A phase I study of intravenous reovirus and docetaxel in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5564–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.G.; Feng, X.; DiFrancesco, L.M.; Fonseca, K.; Forsyth, P.A.; Paterson, A.H.; Coffey, M.C.; Thompson, B. REO-001: A phase I trial of percutaneous intralesional administration of reovirus type 3 dearing (Reolysin(R)) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2013, 31, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sborov, D.W.; Nuovo, G.J.; Stiff, A.; Mace, T.; Lesinski, G.B.; Benson, D.M., Jr.; Efebera, Y.A.; Rosko, A.E.; Pichiorri, F.; Grever, M.R.; et al. A phase I trial of single-agent reolysin in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 5946–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kicielinski, K.P.; Chiocca, E.A.; Yu, J.S.; Gill, G.M.; Coffey, M.; Markert, J.M. Phase 1 clinical trial of intratumoral reovirus infusion for the treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas in adults. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1056–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, E.A.; Sampson, V.; Stabley, D.; Walter, A.; Sol-Church, K.; Cripe, T.; Hingorani, P.; Ahern, C.H.; Weigel, B.J.; Zwiebel, J.; et al. A phase I trial and viral clearance study of reovirus (Reolysin) in children with relapsed or refractory extra-cranial solid tumors: A Children’s Oncology Group Phase I Consortium report. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desjardins, A.; Gromeier, M.; Herndon, J.E., 2nd; Beaubier, N.; Bolognesi, D.P.; Friedman, A.H.; Friedman, H.S.; McSherry, F.; Muscat, A.M.; Nair, S.; et al. Recurrent Glioblastoma Treated with Recombinant Poliovirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, V.; Diaconu, I.; Kangasniemi, L.; Rajecki, M.; Escutenaire, S.; Koski, A.; Romano, V.; Rouvinen, N.; Tuuminen, T.; Laasonen, L.; et al. Immunological effects of low-dose cyclophosphamide in cancer patients treated with oncolytic adenovirus. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Dmitriev, I.P.; Saddekni, S.; Kashentseva, E.A.; Harris, R.D.; Aurigemma, R.; Bae, S.; Singh, K.P.; Siegal, G.P.; Curiel, D.T.; et al. A phase I clinical trial of Ad5/3-Delta24, a novel serotype-chimeric, infectivity-enhanced, conditionally-replicative adenovirus (CRAd), in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 130, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, K.J.; Preuss, M.A.; Barnes, M.N.; Wang, M.; Siegal, G.P.; Wan, W.; Kuo, H.; Saddekni, S.; Stockard, C.R.; Grizzle, W.E.; et al. A phase I study of a tropism-modified conditionally replicative adenovirus for recurrent malignant gynecologic diseases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5277–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, S.; Diaconu, I.; Cerullo, V.; Escutenaire, S.; Raki, M.; Kangasniemi, L.; Nokisalmi, P.; Dotti, G.; Guse, K.; Laasonen, L.; et al. Integrin targeted oncolytic adenoviruses Ad5-D24-RGD and Ad5-RGD-D24-GMCSF for treatment of patients with advanced chemotherapy refractory solid tumors. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 1937–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, A.; Nokisalmi, P.; Diaconu, I.; Koski, A.; Cerullo, V.; Liikanen, I.; Tahtinen, S.; Oksanen, M.; Heiskanen, R.; Pesonen, S.; et al. Antiviral and antitumor T-cell immunity in patients treated with GM-CSF-coding oncolytic adenovirus. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 2734–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemminki, O.; Parviainen, S.; Juhila, J.; Turkki, R.; Linder, N.; Lundin, J.; Kankainen, M.; Ristimaki, A.; Koski, A.; Liikanen, I.; et al. Immunological data from cancer patients treated with Ad5/3-E2F-Delta24-GMCSF suggests utility for tumor immunotherapy. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 4467–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWeese, T.L.; van der Poel, H.; Li, S.; Mikhak, B.; Drew, R.; Goemann, M.; Hamper, U.; DeJong, R.; Detorie, N.; Rodriguez, R.; et al. A phase I trial of CV706, a replication-competent, PSA selective oncolytic adenovirus, for the treatment of locally recurrent prostate cancer following radiation therapy. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 7464–7472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Small, E.J.; Carducci, M.A.; Burke, J.M.; Rodriguez, R.; Fong, L.; van Ummersen, L.; Yu, D.C.; Aimi, J.; Ando, D.; Working, P.; et al. A phase I trial of intravenous CG7870, a replication-selective, prostate-specific antigen-targeted oncolytic adenovirus, for the treatment of hormone-refractory, metastatic prostate cancer. Mol. Ther. 2006, 14, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.M.; Lamm, D.L.; Meng, M.V.; Nemunaitis, J.J.; Stephenson, J.J.; Arseneau, J.C.; Aimi, J.; Lerner, S.; Yeung, A.W.; Kazarian, T.; et al. A first in human phase 1 study of CG0070, a GM-CSF expressing oncolytic adenovirus, for the treatment of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J. Urol. 2012, 188, 2391–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Guo, Y.; Guo, H.; Cao, J.; Guo, Y.; Lou, D.; Yu, D.; Li, J. A Phase I study of KH901, a conditionally replicating granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: Armed oncolytic adenovirus for the treatment of head and neck cancers. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009, 8, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokisalmi, P.; Pesonen, S.; Escutenaire, S.; Sarkioja, M.; Raki, M.; Cerullo, V.; Laasonen, L.; Alemany, R.; Rojas, J.; Cascallo, M.; et al. Oncolytic adenovirus ICOVIR-7 in patients with advanced and refractory solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3035–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Liu, H.L.; Zhang, X.R.; Xu, J.P.; Hu, W.K.; Liang, M.; Chen, S.Y.; Hu, F.; Chu, D.T. A phase I trial of intratumoral administration of recombinant oncolytic adenovirus overexpressing HSP70 in advanced solid tumor patients. Gene Ther 2009, 16, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocca, E.A.; Abbed, K.M.; Tatter, S.; Louis, D.N.; Hochberg, F.H.; Barker, F.; Kracher, J.; Grossman, S.A.; Fisher, J.D.; Carson, K.; et al. A phase I open-label, dose-escalation, multi-institutional trial of injection with an E1B-Attenuated adenovirus, ONYX-015, into the peritumoral region of recurrent malignant gliomas, in the adjuvant setting. Mol. Ther. 2004, 10, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemunaitis, J.; Senzer, N.; Sarmiento, S.; Zhang, Y.A.; Arzaga, R.; Sands, B.; Maples, P.; Tong, A.W. A phase I trial of intravenous infusion of ONYX-015 and enbrel in solid tumor patients. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007, 14, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganly, I.; Kirn, D.; Eckhardt, G.; Rodriguez, G.I.; Soutar, D.S.; Otto, R.; Robertson, A.G.; Park, O.; Gulley, M.L.; Heise, C.; et al. A phase I study of Onyx-015, an E1B attenuated adenovirus, administered intratumorally to patients with recurrent head and neck cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 798–806. [Google Scholar]

- Nemunaitis, J.; Tong, A.W.; Nemunaitis, M.; Senzer, N.; Phadke, A.P.; Bedell, C.; Adams, N.; Zhang, Y.A.; Maples, P.B.; Chen, S.; et al. A phase I study of telomerase-specific replication competent oncolytic adenovirus (telomelysin) for various solid tumors. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Salazar, R.; Duran, I.; Osman-Garcia, I.; Paz-Ares, L.; Bozada, J.M.; Boni, V.; Blanc, C.; Seymour, L.; Beadle, J.; et al. Phase 1 study of intravenous administration of the chimeric adenovirus enadenotucirev in patients undergoing primary tumor resection. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freytag, S.O.; Khil, M.; Stricker, H.; Peabody, J.; Menon, M.; DePeralta-Venturina, M.; Nafziger, D.; Pegg, J.; Paielli, D.; Brown, S.; et al. Phase I study of replication-competent adenovirus-mediated double suicide gene therapy for the treatment of locally recurrent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4968–4976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freytag, S.O.; Stricker, H.; Peabody, J.; Pegg, J.; Paielli, D.; Movsas, B.; Barton, K.N.; Brown, S.L.; Lu, M.; Kim, J.H. Five-year follow-up of trial of replication-competent adenovirus-mediated suicide gene therapy for treatment of prostate cancer. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, S.O.; Stricker, H.; Pegg, J.; Paielli, D.; Pradhan, D.G.; Peabody, J.; DePeralta-Venturina, M.; Xia, X.; Brown, S.; Lu, M.; et al. Phase I study of replication-competent adenovirus-mediated double-suicide gene therapy in combination with conventional-dose three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed, intermediate- to high-risk prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 7497–7506. [Google Scholar]

- Freytag, S.O.; Movsas, B.; Aref, I.; Stricker, H.; Peabody, J.; Pegg, J.; Zhang, Y.; Barton, K.N.; Brown, S.L.; Lu, M.; et al. Phase I trial of replication-competent adenovirus-mediated suicide gene therapy combined with IMRT for prostate cancer. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.H.; Hwang, T.; Liu, T.C.; Sze, D.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kwon, H.C.; Oh, S.Y.; Han, S.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Hong, S.H.; et al. Use of a targeted oncolytic poxvirus, JX-594, in patients with refractory primary or metastatic liver cancer: A phase I trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.H.; Moon, A.; Burke, J.; Ribas, A.; Stephenson, J.; Breitbach, C.J.; Daneshmand, M.; De Silva, N.; Parato, K.; Diallo, J.S.; et al. A mechanistic proof-of-concept clinical trial with JX-594, a targeted multi-mechanistic oncolytic poxvirus, in patients with metastatic melanoma. Mol. Ther. 2011, 19, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripe, T.P.; Ngo, M.C.; Geller, J.I.; Louis, C.U.; Currier, M.A.; Racadio, J.M.; Towbin, A.J.; Rooney, C.M.; Pelusio, A.; Moon, A.; et al. Phase 1 study of intratumoral Pexa-Vec (JX-594), an oncolytic and immunotherapeutic vaccinia virus, in pediatric cancer patients. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Breitbach, C.J.; Lee, J.; Park, J.O.; Lim, H.Y.; Kang, W.K.; Moon, A.; Mun, J.H.; Sommermann, E.M.; Maruri Avidal, L.; et al. Phase 1b Trial of Biweekly Intravenous Pexa-Vec (JX-594), an Oncolytic and Immunotherapeutic Vaccinia Virus in Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseini, F.; Delord, J.P.; Fournel-Federico, C.; Guitton, J.; Erbs, P.; Homerin, M.; Halluard, C.; Jemming, C.; Orange, C.; Limacher, J.M.; et al. Vectorized gene therapy of liver tumors: Proof-of-concept of TG4023 (MVA-FCU1) in combination with flucytosine. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mell, L.K.; Brumund, K.T.; Daniels, G.A.; Advani, S.J.; Zakeri, K.; Wright, M.E.; Onyeama, S.J.; Weisman, R.A.; Sanghvi, P.R.; Martin, P.J.; et al. Phase I Trial of Intravenous Oncolytic Vaccinia Virus (GL-ONC1) with Cisplatin and Radiotherapy in Patients with Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5696–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeh, H.J.; Downs-Canner, S.; McCart, J.A.; Guo, Z.S.; Rao, U.N.; Ramalingam, L.; Thorne, S.H.; Jones, H.L.; Kalinski, P.; Wieckowski, E.; et al. First-in-man study of western reserve strain oncolytic vaccinia virus: Safety, systemic spread, and antitumor activity. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs-Canner, S.; Guo, Z.S.; Ravindranathan, R.; Breitbach, C.J.; O’Malley, M.E.; Jones, H.L.; Moon, A.; McCart, J.A.; Shuai, Y.; Zeh, H.J.; et al. Phase 1 Study of Intravenous Oncolytic Poxvirus (vvDD) in Patients with Advanced Solid Cancers. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzerling, L.; Kunzi, V.; Oberholzer, P.A.; Kundig, T.; Naim, H.; Dummer, R. Oncolytic measles virus in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas mounts antitumor immune responses in vivo and targets interferon-resistant tumor cells. Blood 2005, 106, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dispenzieri, A.; Tong, C.; LaPlant, B.; Lacy, M.Q.; Laumann, K.; Dingli, D.; Zhou, Y.; Federspiel, M.J.; Gertz, M.A.; Hayman, S.; et al. Phase I trial of systemic administration of Edmonston strain of measles virus genetically engineered to express the sodium iodide symporter in patients with recurrent or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2017, 31, 2791–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, E.; Hartmann, L.C.; Cliby, W.A.; Long, H.J.; Peethambaram, P.P.; Barrette, B.A.; Kaur, J.S.; Haluska, P.J., Jr.; Aderca, I.; Zollman, P.J.; et al. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal administration of an oncolytic measles virus strain engineered to express carcinoembryonic antigen for recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Ahern, C.; Weigel, B.J.; Poirier, J.T.; Rudin, C.M.; Chen, Y.; Cripe, T.P.; Bernhardt, M.B.; Blaney, S.M. Phase I trial of Seneca Valley Virus (NTX-010) in children with relapsed/refractory solid tumors: A report of the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2015, 62, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Poirier, J.T.; Senzer, N.N.; Stephenson, J., Jr.; Loesch, D.; Burroughs, K.D.; Reddy, P.S.; Hann, C.L.; Hallenbeck, P.L. Phase I clinical study of Seneca Valley Virus (SVV-001), a replication-competent picornavirus, in advanced solid tumors with neuroendocrine features. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, A.; Kasuya, H.; Sahin, T.T.; Nomura, N.; Kanzaki, A.; Misawa, M.; Shirota, T.; Yamada, S.; Fujii, T.; Sugimoto, H.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation clinical trial of intraoperative direct intratumoral injection of HF10 oncolytic virus in non-resectable patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2011, 18, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirooka, Y.; Kasuya, H.; Ishikawa, T.; Kawashima, H.; Ohno, E.; Villalobos, I.B.; Naoe, Y.; Ichinose, T.; Koyama, N.; Tanaka, M.; et al. A Phase I clinical trial of EUS-guided intratumoral injection of the oncolytic virus, HF10 for unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, H.L.; Kim, D.W.; Kim-Schulze, S.; DeRaffele, G.; Jagoda, M.C.; Broucek, J.R.; Zloza, A. Results of a randomized phase I gene therapy clinical trial of nononcolytic fowlpox viruses encoding T cell costimulatory molecules. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014, 25, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossardt, C.; Engeland, C.E.; Bossow, S.; Halama, N.; Zaoui, K.; Leber, M.F.; Springfeld, C.; Jaeger, D.; von Kalle, C.; Ungerechts, G. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-armed oncolytic measles virus is an effective therapeutic cancer vaccine. Hum. Gene Ther. 2013, 24, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Reid, T.; Ruo, L.; Breitbach, C.J.; Rose, S.; Bloomston, M.; Cho, M.; Lim, H.Y.; Chung, H.C.; Kim, C.W.; et al. Randomized dose-finding clinical trial of oncolytic immunotherapeutic vaccinia JX-594 in liver cancer. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, D.E.; Sill, M.W.; Walker, J.L.; O’Malley, D.; Nagel, C.I.; Rutledge, T.L.; Bradley, W.; Richardson, D.L.; Moxley, K.M.; Aghajanian, C. Randomized phase IIB evaluation of weekly paclitaxel versus weekly paclitaxel with oncolytic reovirus (Reolysin(R)) in recurrent ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer: An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 146, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, E.; Markovic, S.N.; Suman, V.J.; Nuovo, G.J.; Vile, R.G.; Kottke, T.J.; Nevala, W.K.; Thompson, M.A.; Lewis, J.E.; Rumilla, K.M.; et al. Phase II trial of intravenous administration of Reolysin((R)) (Reovirus Serotype-3-dearing Strain) in patients with metastatic melanoma. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 1998–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, D.; Fountzilas, C.; Moseley, J.; Noronha, N.; Tran, H.; Chakrabarty, R.; Selvaggi, G.; Coffey, M.; Thompson, B.; Sarantopoulos, J. A phase II study of REOLYSIN((R)) (pelareorep) in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with advanced malignant melanoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 79, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, A.M.; Farren, M.R.; Geyer, S.M.; Huang, Y.; Tahiri, S.; Ahn, D.; Mikhail, S.; Ciombor, K.K.; Pant, S.; Aparo, S.; et al. Randomized Phase 2 Trial of the Oncolytic Virus Pelareorep (Reolysin) in Upfront Treatment of Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, D.; Goel, S.; Aparo, S.; Patel Arora, S.; Noronha, N.; Tran, H.; Chakrabarty, R.; Selvaggi, G.; Gutierrez, A.; Coffey, M.; et al. A Phase II Study of Pelareorep (REOLYSIN((R))) in Combination with Gemcitabine for Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2018, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, V.; Ellard, S.L.; Dent, S.F.; Tu, D.; Mates, M.; Dhesy-Thind, S.K.; Panasci, L.; Gelmon, K.A.; Salim, M.; Song, X.; et al. A randomized phase II study of weekly paclitaxel with or without pelareorep in patients with metastatic breast cancer: Final analysis of Canadian Cancer Trials Group IND.213. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, S.O.; Stricker, H.; Lu, M.; Elshaikh, M.; Aref, I.; Pradhan, D.; Levin, K.; Kim, J.H.; Peabody, J.; Siddiqui, F.; et al. Prospective randomized phase 2 trial of intensity modulated radiation therapy with or without oncolytic adenovirus-mediated cytotoxic gene therapy in intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014, 89, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Martinez, A.; Manzanera, A.G.; Sukin, S.W.; Esteban-Maria, J.; Gonzalez-Guerrero, J.F.; Gomez-Guerra, L.; Garza-Guajardo, R.; Flores-Gutierrez, J.P.; Elizondo Riojas, G.; Delgado-Enciso, I.; et al. Intraprostatic distribution and long-term follow-up after AdV-tk immunotherapy as neoadjuvant to surgery in patients with prostate cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013, 20, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pound, C.R.; Partin, A.W.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Chan, D.W.; Pearson, J.D.; Walsh, P.C. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA 1999, 281, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, L.A.; Manzanera, A.G.; Bell, S.D.; Cavaliere, R.; McGregor, J.M.; Grecula, J.C.; Newton, H.B.; Lo, S.S.; Badie, B.; Portnow, J.; et al. Phase II multicenter study of gene-mediated cytotoxic immunotherapy as adjuvant to surgical resection for newly diagnosed malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2016, 18, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuri, F.R.; Nemunaitis, J.; Ganly, I.; Arseneau, J.; Tannock, I.F.; Romel, L.; Gore, M.; Ironside, J.; MacDougall, R.H.; Heise, C.; et al. A controlled trial of intratumoral ONYX-015, a selectively-replicating adenovirus, in combination with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in patients with recurrent head and neck cancer. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemunaitis, J.; Ganly, I.; Khuri, F.; Arseneau, J.; Kuhn, J.; McCarty, T.; Landers, S.; Maples, P.; Romel, L.; Randlev, B.; et al. Selective replication and oncolysis in p53 mutant tumors with ONYX-015, an E1B-55kD gene-deleted adenovirus, in patients with advanced head and neck cancer: A phase II trial. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 6359–6366. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, T.R.; Freeman, S.; Post, L.; McCormick, F.; Sze, D.Y. Effects of Onyx-015 among metastatic colorectal cancer patients that have failed prior treatment with 5-FU/leucovorin. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packiam, V.T.; Lamm, D.L.; Barocas, D.A.; Trainer, A.; Fand, B.; Davis, R.L., 3rd; Clark, W.; Kroeger, M.; Dumbadze, I.; Chamie, K.; et al. An open label, single-arm, phase II multicenter study of the safety and efficacy of CG0070 oncolytic vector regimen in patients with BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Interim results. Urol. Oncol. 2018, 36, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Breitbach, C.; Cho, M.; Hwang, T.-H.; Kim, C.W.; Jeon, U.B.; Woo, H.Y.; Yoon, K.T.; Lee, J.W.; Burke, J.; et al. Phase II trial of Pexa-Vec (pexastimogene devacirepvec; JX-594), an oncolytic and immunotherapeutic vaccinia virus, followed by sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31 (Suppl. 15), 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.H.; Yuan, Z.Y.; Guan, Z.Z.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.Q.; Hu, X.H.; Feng, J.F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Chen, Z.T.; et al. Phase II clinical study of intratumoral H101, an E1B deleted adenovirus, in combination with chemotherapy in patients with cancer. Ai Zheng 2003, 22, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Annels, N.E.; Mansfield, D.; Arif, M.; Ballesteros-Merino, C.; Simpson, G.R.; Denyer, M.; Sandhu, S.S.; Melcher, A.A.; Harrington, K.J.; Davies, B.; et al. Phase I Trial of an ICAM-1-Targeted Immunotherapeutic-Coxsackievirus A21 (CVA21) as an Oncolytic Agent against Non Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5818–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Study of Intratumoral CAVATAK™ in Patients with Stage IIIc and Stage IV Malignant Melanoma (VLA-007 CALM) (CALM). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01227551 (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Schenk, E.L.; Mandrekar, S.J.; Dy, G.K.; Aubry, M.C.; Tan, A.D.; Dakhil, S.R.; Sachs, B.A.; Nieva, J.J.; Bertino, E.; Lee Hann, C.; et al. A Randomized Double-Blind Phase II Study of the Seneca Valley Virus (NTX-010) versus Placebo for Patients with Extensive-Stage SCLC (ES SCLC) Who Were Stable or Responding after at Least Four Cycles of Platinum-Based Chemotherapy: North Central Cancer Treatment Group (Alliance) N0923 Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.J.; Wasinger, A.M.; Brey, R.N.; Dunleavey, J.M.; St. Croix, B.; Bann, J.G. Seneca Valley Virus Exploits TEM8, a Collagen Receptor Implicated in Tumor Growth. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karapanagiotou, E.M.; Roulstone, V.; Twigger, K.; Ball, M.; Tanay, M.; Nutting, C.; Newbold, K.; Gore, M.E.; Larkin, J.; Syrigos, K.N.; et al. Phase I/II trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in combination with intravenous oncolytic reovirus in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 2080–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geletneky, K.; Hajda, J.; Angelova, A.L.; Leuchs, B.; Capper, D.; Bartsch, A.J.; Neumann, J.O.; Schoning, T.; Husing, J.; Beelte, B.; et al. Oncolytic H-1 Parvovirus Shows Safety and Signs of Immunogenic Activity in a First Phase I/IIa Glioblastoma Trial. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 2620–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, K.J.; Hingorani, M.; Tanay, M.A.; Hickey, J.; Bhide, S.A.; Clarke, P.M.; Renouf, L.C.; Thway, K.; Sibtain, A.; McNeish, I.A.; et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSV GM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 4005–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geevarghese, S.K.; Geller, D.A.; de Haan, H.A.; Horer, M.; Knoll, A.E.; Mescheder, A.; Nemunaitis, J.; Reid, T.R.; Sze, D.Y.; Tanabe, K.K.; et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic herpes simplex virus NV1020 in patients with extensively pretreated refractory colorectal cancer metastatic to the liver. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, E.; Okuno, S.H.; Nascimento, A.G.; Lewis, B.D.; Lee, R.A.; Oliveira, A.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Atherton, P.; Edmonson, J.H.; Erlichman, C.; et al. Phase I-II trial of ONYX-015 in combination with MAP chemotherapy in patients with advanced sarcomas. Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.I.; Zakay-Rones, Z.; Gomori, J.M.; Linetsky, E.; Rasooly, L.; Greenbaum, E.; Rozenman-Yair, S.; Panet, A.; Libson, E.; Irving, C.S.; et al. Phase I/II trial of intravenous NDV-HUJ oncolytic virus in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Mol. Ther. 2006, 13, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemunaitis, J.; Khuri, F.; Ganly, I.; Arseneau, J.; Posner, M.; Vokes, E.; Kuhn, J.; McCarty, T.; Landers, S.; Blackburn, A.; et al. Phase II trial of intratumoral administration of ONYX-015, a replication-selective adenovirus, in patients with refractory head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andtbacka, R.H.; Kaufman, H.L.; Collichio, F.; Amatruda, T.; Senzer, N.; Chesney, J.; Delman, K.A.; Spitler, L.E.; Puzanov, I.; Agarwala, S.S.; et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2780–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesney, J.; Awasthi, S.; Curti, B.; Hutchins, L.; Linette, G.; Triozzi, P.; Tan, M.C.B.; Brown, R.E.; Nemunaitis, J.; Whitman, E.; et al. Phase IIIb safety results from an expanded-access protocol of talimogene laherparepvec for patients with unresected, stage IIIB-IVM1c melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2018, 28, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlhapp, F.J.; Kaufman, H.L. Molecular Pathways: Mechanism of Action for Talimogene Laherparepvec, a New Oncolytic Virus Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzanov, I.; Milhem, M.M.; Minor, D.; Hamid, O.; Li, A.; Chen, L.; Chastain, M.; Gorski, K.S.; Anderson, A.; Chou, J.; et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination with Ipilimumab in Previously Untreated, Unresectable Stage IIIB-IV Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemany, R.; Suzuki, K.; Curiel, D.T. Blood clearance rates of adenovirus type 5 in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81 Pt 11, 2605–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.L.; Fields, B.N. Reoviruses. In Virology, 2nd ed.; Fields, B.N., Knipe, D.M., Chanock, R.M., Hirsch, M.S., Melnick, J.L., Monath, T.P., Roizman, B., Eds.; Raven Press, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 1307–1328. [Google Scholar]