Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Salinity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Types of Reactive Oxygen Species

3. ROS Generation in Plant Cells

4. Consequence of ROS in Plant Cells

5. Plant Responses to Salinity

5.1. Germination

5.2. Growth

5.3. Photosynthesis

5.4. Ionic Imbalance

5.5. Water Relation

5.6. Anatomical Modifications

5.7. Crop Yield

5.8. Crop Quality

6. Salinity-Induced Oxidative Stress in Plants

7. Antioxidant Defense System in Plants under Salinity

8. Signaling of ROS in the Regulation of Salinity

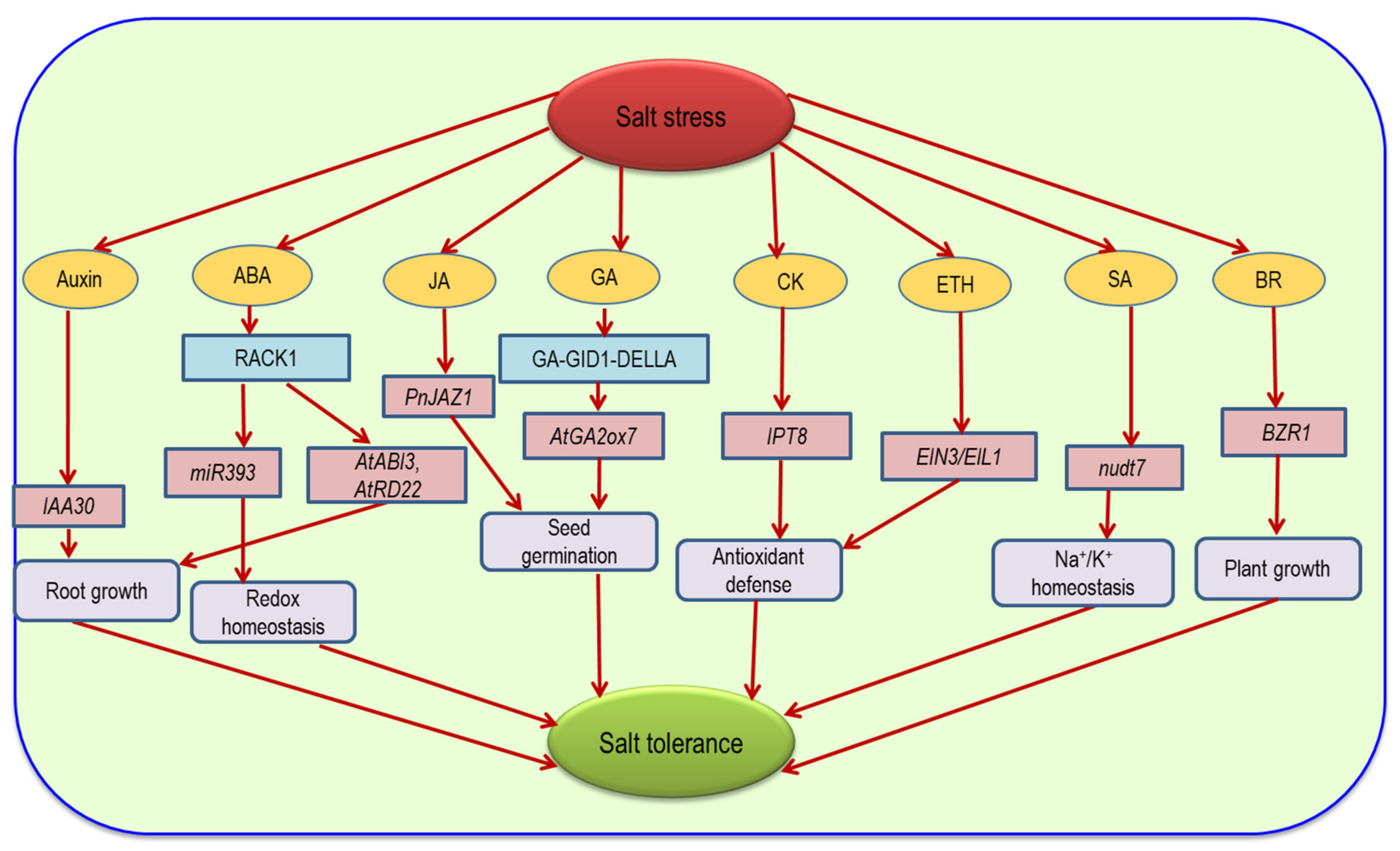

9. Hormonal Regulation and ROS under Salinity

10. Gene Regulation for Antioxidant Defense under Salinity

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yadav, S.; Modi, P.; Dave, A.; Vijapura, A.; Patel, D.; Patel, M. Effect of abiotic stress on crops. In Sustainable Crop Production; Hasanuzzaman, M., Filho, M.C.M.T., Fujita, M., Nogueira, T.A.R., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: Revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, R. Modulation of ethylene and ascorbic acid on reactive oxygen species scavenging in plant salt response. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2021. Available online: http://www.fao.org/global-soil-partnership/resources/highlights/detail/en/c/1412475/ (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Plant response to salt stress and role of exogenous protectants to mitigate salt-induced damages. In Ecophysiology and Responses of Plants under Salt Stress; Ahmed, P., Azooz, M.M., Prasad, M.N.V., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 25–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.S.; Dietz, K.J. Tuning of redox regulatory mechanisms, reactive oxygen species and redox homeostasis under salinity stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharjee, S. ROS and oxidative stress: Origin and implication. In Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Biology; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Anee, T.I.; Parvin, K.; Nahar, K.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M. Regulation of ascorbate-glutathione pathway in mitigating oxidative damage in plants under abiotic stress. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munns, R.; Gilliham, M. Salinity tolerance of crops—What is the cost? New Phytol. 2015, 208, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mittler, R. ROS are good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saini, P.; Gani, M.; Kaur, J.J.; Godara, L.C.; Singh, C.; Chauhan, S.S.; Francies, R.M.; Bhardwaj, A.; Kumar, N.B.; Ghosh, M.K. Reactive oxygen species (ROS): A way to stress survival in plants. In Abiotic Stress-Mediated Sensing and Signaling in Plants: An Omics Perspective; Zargar, S., Zargar, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, A.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, N. ROS and oxidative burst: Roots in plant development. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, S.; Ansari, S.A.; Ansari, M.I.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: Generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, R.; Hussain, S.; Anjum, M.A.; Khalid, M.F.; Saqib, M.; Zakir, I.; Ahmad, S. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense mechanisms in plants under salt stress. In Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Hasanuzzaman, M., Hakeem, K.R., Nahar, K., Alharby, H.F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Mhamdi, A.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species in plant development. Development 2018, 145, dev164376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guan, L.; Haider, M.S.; Khan, N.; Nasim, M.; Jiu, S.; Fiaz, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, K.; Fang, J. Transcriptome sequence analysis elaborates a complex defensive mechanism of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) in response to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, B.; Qin, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, H. Progress in understanding the physiological and molecular responses of Populus to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández, J.A. Salinity tolerance in plants: Trends and perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, X.; Kiprotich, F.; Han, H.; Guan, R.; Wang, R.; Shen, W. Nitric oxide is required for melatonin-enhanced tolerance against salinity stress in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) seedlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos-Sánchez, N.F.; Salas-Coronado, R.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C.; Hernández-Carlos, B. Antioxidant compounds and their antioxidant mechanism. In Antioxidants; Shalaby, E., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Duan, X.; Luo, L.; Dai, S.; Ding, Z.; Xia, G. How plant hormones mediate salt stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, J.R. Application of mitochondria-targeted pharmaceuticals for the treatment of heart disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 4763–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.; Parvin, K.; Bhuiyan, T.F.; Anee, T.I.; Nahar, K.; Hossen, M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Alam, M.; Fujita, M. Regulation of ROS metabolism in plants under environmental stress: A review of recent experimental evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, S.K.; Khanna, K.; Bhardwaj, R.; Abd Allah, E.F.; Ahmad, P.; Corpas, F.J. Assessment of subcellular ROS and NO metabolism in higher plants: Multifunctional signaling molecules. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Podgorska, A.; Burian, M.; Szal, B. Extra-cellular but extra-ordinarily important for cells: Apoplastic reactive oxygen species metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janků, M.; Luhová, L.; Petřivalský, M. On the origin and fate of reactive oxygen species in plant cell compartments. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raja, V.; Majeed, U.; Kang, H.; Andrabi, K.I.; John, R. Abiotic stress: Interplay between ROS, hormones and MAPKs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heyno, E.; Mary, V.; Schopfer, P.; Krieger-Liszkay, A. Oxygen activation at the plasma membrane: Relation between superoxide and hydroxyl radical production by isolated membranes. Planta 2011, 234, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, K.J. Thiol-based peroxidases and ascorbate peroxidases: Why plants rely on multiple peroxidase systems in the photosynthesizing chloroplast? Mol. Cells 2016, 39, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Shakirova, F.M.; Allagulova, C.R.; Maslennikova, D.R.; Klyuchnikova, E.O.; Avalbaev, A.M.; Bezrukova, M.V. Salicylic acid-induced protection against cadmium toxicity in wheat plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 122, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, S.; Singh, I.K. Reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling during abiotic stress. Plant Gene 2019, 18, 100–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; VanAken, O.; Schwarzländer, M.; Belt, K.; Millar, A.H. The roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in cellular signaling and stress responses in plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerchev, P.; Waszczak, C.; Lewandowska, A.; Willems, P.; Shapiguzov, A.; Li, Z. Lack of GLYCOLATE OXIDASE1, but not GLYCOLATE OXIDASE2, attenuates the photorespiratory phenotype of CATALASE2- deficient Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1704–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox regulation in photosynthetic organisms: Signaling, acclimation, and practical implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 861–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpas, F.J.; del Río, L.A.; Palma, J.M. Impact of nitric oxide (NO) on the ROS metabolism of peroxisomes. Plants 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reumann, S.; Chowdhary, G.; Lingner, T. Characterization, prediction and evolution of plant peroxisomal targeting signals type 1 (PTS1s). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.J.; Prasad, R.S.; Banerjee, R.; Thammineni, C. Seed birth to death: Dual functions of reactive oxygen species in seed physiology. Ann. Bot. 2015, 116, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Breusegem, F.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Mittler, R. Unraveling the tapestry of networks involving reactive oxygen species in plants. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, K.; Chaturvedi, V.; Gupta, S. Climate change and abiotic stress-induced oxidative burst in rice. In Advances in Rice Research for Abiotic Stress Tolerance; Hasanuzzaman, M., Fujita, M., Nahar, K., Biswas, J.K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 505–535. [Google Scholar]

- Alché, J.D. A concise appraisal of lipid oxidation and lipoxidation in higher plants. Redox Biol. 2019, 23, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.A.; Sofo, A.; Scopa, A. Lipids and proteins—Major targets of oxidative modifications in abiotic stressed plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 4099–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P. Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II as a response to light and temperature stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 26, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Abiotic stress, generation of reactive oxygen species, and their consequences: An overview. In Reactive Oxygen Species in Plants: Boon or Bane- Revisiting the Role of ROS; Singh, V.P., Singh, S., Tripathi, D.K., Prasad, S.M., Chauhan, D.K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2018; pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, M.; Laxa, M.; Sweetlove, L.J.; Fernie, A.R.; Obata, T. Metabolic recovery of Arabidopsis thaliana roots following cessation of oxidative stress. Metabolomics 2012, 8, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Babu, M.A.; Singh, D.; Gothandam, K.M. The effect of salinity on growth, hormones and mineral elements in leaf and fruit of tomato cultivar PKM1. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2012, 22, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wahid, A.; Farooq, M.; Basra, S.M.A.; Rasul, E.; Siddique, K.H.M. Germination of seeds and propagules under salt stress. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress; Pessarakli, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 321–337. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Xia, W.; Li, H.; Zeng, H.; Wei, B.; Han, S.; Yin, C. Salinity inhibits rice seed germination by reducing α-Amylase activity via decreased bioactive gibberellin content. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Qi, Y.; Chen, F.; Meng, Y.; Luo, X.; Shuai, H.; Zhou, W.; Ding, J.; Du, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Salt stress represses soybean seed germination by negatively regulating GA biosynthesis while positively mediating ABA biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.-F.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, M.; Ren, X.-Y.; Han, L.; Wang, J.-D.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Fan, X.-L.; Liu, Q.-Q. Gibberelin recovers seed germination in rice with impaired brassinosteroid signalling. Plant Sci. 2020, 293, 110435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadshani, S.; Sharma, R.C.; Baum, M.; Ogbonnaya, F.C.; Leon, J.; Ballvora, A. Multidimensional evaluation of response to salt stress in wheat. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.-Q.; Jiao, Q.; Shui, Q.-Z. Effect of salinity on seed germination, seedling growth, and inorganic and organic solutes accumulation in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Plant Soil Environ. 2015, 61, 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bistgani, Z.E.; Hashemi, M.; DaCosta, M.; Craker, L.; Maggi, F.; Morshedloo, M.R. Effect of salinity stress on the physiological characteristics, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Thymus vulgaris L. and Thymus daenensis Celak. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019, 135, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, K.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Mohsin, S.M.; Fujita, M. Exogenous vanillic acid enhances salt tolerance of tomato: Insight into plant antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 150, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazher, A.M.A.; El-Quesni, E.M.F.; Farahat, M.M. Responses of ornamental and woody trees to salinity. World J. Agric. Sci. 2007, 3, 386–395. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, O.K.; Mekapogu, M.; Kim, K.S. Effect of salinity stress on photosynthesis and related physiological responses in carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, Z.; Challabathula, D. Protection of photosynthesis by halotolerant Staphylococcus sciuri ET101 in tomato (Lycoperiscon esculentum) and rice (Oryza sativa) plants during salinity stress: Possible interplay between carboxylation and oxygenation in stress mitigation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 547750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsin, S.M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Parvin, K.; Fujita, M. Pretreatment of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings with 2,4-D improves tolerance to salinity-induced oxidative stress and methylglyoxal toxicity by modulating ion homeostasis, antioxidant defenses, and glyoxalase systems. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 152, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvin, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Nahar, K.; Mohsin, S.M.; Fujita, M. Comparative physiological and biochemical changes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) under salt stress and recovery: Role of antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Labrada, F.; López-Vargas, E.R.; Ortega-Ortiz, H.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Responses of tomato plants under saline stress to foliar application of copper nanoparticles. Plants 2019, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Inafuku, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M.; Oku, H. Nitric oxide regulates plant growth, physiology, antioxidant defense, and ion homeostasis to confer salt tolerance in the mangrove species, Kandelia obovata. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Alam, M.U.; Rahman, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Mahmud, J.-A.; Fujita, M. Use of iso-osmotic solution to understand salt stress responses in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 113, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Du, J.; Feng, H.; Blumwald, E.; Yu, L.; Xu, G. Two NHX-type transporters from Helianthus tuberosus improve the tolerance of rice to salinity and nutrient deficiency stress. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bose, J.; Rodrigo-Moreno, A.; Shabala, S. ROS homeostasis in halophytes in the context of salinity stress tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahman, A.; Alam, M.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Suzuki, T.; Fujita, M. Polyamines confer salt tolerance in mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) by reducing sodium uptake, improving nutrient homeostasis, antioxidant defense, and methylglyoxal detoxification systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekawya, A.M.M.; Abdelazizc, M.N.; Ueda, A. Apigenin pretreatment enhances growth and salinity tolerance of rice seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 130, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Calcium supplementation improves Na+/K+ ratio, antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems in salt-stressed rice seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, A.; Hossain, M.S.; Mahmud, J.-A.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Manganese-induced salt stress tolerance in rice seedlings: Regulation of ion homeostasis, antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2016, 22, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, G.M.; Fragasso, M.; Nigro, F.; Platani, C.; Papa, R.; Beleggia, R.; Trono, D. Analysis of metabolic and mineral changes in response to salt stress in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. durum) genotypes, which differ in salinity tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 133, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalta, I.; Reina-Sanchez, A.; Bolarin, M.C.; Cuartero, J.; Belver, A.; Venema, K.; Carbonell, E.A.; Asins, M.J. Genetic analysis of Na+ and K+ concentrations in leaf and stem as physiological components of salt tolerance in tomato. Theor. Appl. Gene 2008, 116, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Alam, M.M.; Rahman, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Exogenous proline and glycine betaine mediated upregulation of antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems provides better protection against salt-induced oxidative stress in two rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 757219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, C.; An, L.; Jiao, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, G.; McLaughlin, N. Effects of gibberellic acid on water uptake and germination of sweet sorghum seeds under salinity stress. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 2019, 79, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeeshan, M.; Lu, M.; Sehar, S.; Holford, P.; Wu, F. Comparison of biochemical, anatomical, morphological, and physiological responses to salinity stress in wheat and barley genotypes deferring in salinity tolerance. Agronomy 2020, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogoutdinova, L.R.; Lazareva, E.M.; Chaban, I.A.; Kononenko, N.V.; Dilovarova, T.; Khaliluev, M.R.; Kurenina, L.V.; Gulevich, A.A.; Smirnova, E.A.; Baranova, E.N. Salt stress-induced structural changes are mitigated in transgenic tomato plants over-expressing superoxide dismutase. Biology 2020, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Zhang, W.; Ma, X. Cerium oxide nanoparticles alter the salt stress tolerance of Brassica napus L. by modifying the formation of root apoplastic barriers. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughalleb, F.; Abdellaoui, R.; Nbiba, N.; Mahmoudi, M.; Neffati, M. Effect of NaCl stress on physiological, antioxidant enzymes and anatomical responses of Astragalus gombiformis. Biologia 2017, 72, 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, B.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Rehman, M.T.; Khan, N.A. Treatment of nitric oxide supplemented with nitrogen and sulfur regulates photosynthetic performance and stomatal behavior in mustard under salt stress. Physiol. Plant 2020, 168, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sehar, Z.; Masood, A.; Khan, N.A. Nitric oxide reverses glucose-mediated photosynthetic repression in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under salt stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 161, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Iqbal, N.; Gautam, H.; Sehar, Z.; Sofo, A.; D’Ippolito, I.; Khan, N.A. Ethylene and sulfur coordinately modulate the antioxidant system and ABA accumulation in mustard plants under salt stress. Plants 2021, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.A.; Elhamid, E.M.A.; Sadak, M.S. Comparative study for the effect of arginine and sodium nitroprusside on sunflower plants grown under salinity stress conditions. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreen, S.; Sultan, M.; Akhter, M.S.; Shah, K.H.; Ummara, U.; Manzoor, H.; Ulfat, M.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. Foliar fertigation of ascorbic acid and zinc improves growth, antioxidant enzyme activity and harvest index in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) grown under salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Gogoi, N.; Barthakur, S.; Baroowa, B.; Bharadwaj, N.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Draught stress in grain legume during reproduction and grain filling. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 2017, 203, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Luo, J.; Zhao, X.; Dong, H.; Ma, Y.; Sui, N.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, Y. Effects of soil salinity on sucrose metabolism in cotton fiber. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khanam, D.; Mohammad, F. Plant growth regulators ameliorate the ill effect of salt stress through improved growth, photosynthesis, antioxidant system, yield and quality attributes in Mentha piperita L. Acta Physiol. Plant 2018, 40, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costan, A.; Stamatakis, A.; Chrysargyris, A.; Petropoulosc, S.A.; Tzortzakisb, N. Interactive effects of salinity and silicon application on Solanum lycopersicum growth, physiology and shelf-life of fruit produced hydroponically. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Senge, M.; Dai, Y. Effects of salinity stress at different growth stages on tomato growth, yield and water use efficiency. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2017, 48, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.Z.; Mele, M.A.; Choi, K.Y.; Kang, H.M. Nutrient and salinity concentrations effects on quality and storability of cherry tomato fruits grown by hydroponic system. Bragantia 2018, 77, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jalil, S.U.; Ansari, M.I. Physiological role of Gamma-aminobutyric acid in salt stress tolerance. In Salt and Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants; Hasanuzzaman, M., Tanveer, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Geilfus, C.M.; Mithöfer, A.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Zörb, C.; Muehling, K.H. Chloride-inducible transient apoplastic alkalinazations induce stomata closure by controlling abscisic acid distribution between leaf apoplast and guard cells in salt-stressed Vicia faba. New Phytol. 2015, 208, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Alamri, S.; Alsubaie, Q.D.; Ali, H.M. Melatonin and gibberellic acid promote growth and chlorophyll biosynthesis by regulating antioxidant and methylglyoxal detoxification system in tomato seedlings under salinity. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 1488–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Jeddi, K.; Attia, M.S.; Elsayed, S.M.; Yusuf, M.; Osman, M.S.; Soliman, M.H.; Hessini, K. Wuxal amino (Bio stimulant) improved growth and physiological performance of tomato plants under salinity stress through adaptive mechanisms and antioxidant potential. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3204–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Mitra, S.; Paul, A. Physiochemical studies of sodium chloride on mungbean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) and its possible recovery with spermine and gibberellic acid. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 858016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nxele, X.; Klein, A.; Ndimba, B.K. Drought and salinity stress alters ROS accumulation, water retention, and osmolyte content in sorghum plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 108, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, Z.; Fayyaz, H.A.; Irshad, F.; Hussain, N.; Hassan, M.N.; Li, J.; Rehman, S.; Haider, W.; Yasmin, H.; Mumtaz, S.; et al. Sodium nitroprusside application improves morphological and physiological attributes of soybean (Glycine max L.) under salinity stress. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbali, W.; Goussi, R.; Koyro, H.-W.; Abdelly, C.; Manaa, A. Physiological and biochemical markers for screening salt tolerant quinoa genotypes at early seedling stage. J. Plant Interact. 2020, 15, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Derbali, W.; Manaa, A.; Goussi, R.; Derbali, I.; Abdelly, C.; Koyro, H.-W. Post-stress restorative response of two quinoa genotypes differing in their salt resistance after salinity release. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 164, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Fujita, M. Nitric oxide modulates antioxidant defense and the methylglyoxal detoxification system and reduces salinity-induced damage of wheat seedlings. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2011, 5, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Fujita, M. Selenium-induced up-regulation of the antioxidant defense and methylglyoxal detoxification system reduces salinity-induced damage in rapeseed seedlings. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 143, 1704–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, S.; Jain, S.; Jain, V. Salinity induced oxidative stress and antioxidant system in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive cultivars of rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 22, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manai, J.; Kalai, T.; Gouia, H.; Corpas, F.J. Exogenous nitric oxide (NO) ameliorates salinity-induced oxidative stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014, 14, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wutipraditkul, N.; Wongwean, P.; Buaboocha, T. Alleviation of salt-induced oxidative stress in rice seedlings by proline and/or glycinebetaine. Biol. Plant 2015, 59, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Vaishnav, A.; Jain, S.; Verma, A.; Choudhary, D.K. Bacterial-mediated induction of systemic tolerance to salinity with expression of stress alleviating enzymes in soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill). J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 34, 558–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, N.B. Effective microorganisms improve growth performance and modulate the ROS-scavenging system in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants exposed to salinity stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 34, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Umar, S.; Khan, N.A. Nitrogen availability regulates proline and ethylene production and alleviates salinity stress in mustard (Brassica juncea). J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 178, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xia, S.; Su, Y.; Wang, H.; Luo, W.; Su, S.; Xiao, L. Brassinolide increases potato root growth In Vitro in a dose-dependent way and alleviates salinity stress. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8231873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taïbi, K.; Taïbi, F.; Abderrahim, L.A.; Ennajah, A.; Belkhodja, M.; Mulet, J.M. Effect of salt stress on growth, chlorophyll content, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant defence systems in Phaseolus vulgaris L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 105, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadu, S.; Dewangan, T.L.; Chandrakar, V.; Keshavkant, S. Imperative roles of salicylic acid and nitric oxide in improving salinity tolerance in Pisum sativum L. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaur, H.; Bhardwaj, R.D.; Grewal, S.K. Mitigation of salinity-induced oxidative damage in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings by exogenous application of phenolic acids. Acta Physiol. Plant 2017, 39, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, R.; Jain, V.; Jain, S. Differential behavior of the antioxidant system in response to salinity induced oxidative stress in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive cultivars of Brassica juncea L. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 13, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefian, M.; Vessal, S.; Shafaroudi, S.M.; Bagheri, A. Comparative analysis of the reaction to salinity of different chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes: A biochemical, enzymatic and transcriptional study. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Han, W.-Y.; Chen, S. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate alleviates salinity-retarded seed germination and oxidative stress in tomato. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 37, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Rohman, M.M.; Anee, T.I.; Huang, Y.; Fujita, M. Exogenous silicon protects Brassica napus plants from salinity-induced oxidative stress through the modulation of AsA-GSH pathway, thiol-dependent antioxidant enzymes and glyoxalase systems. Gesunde Pflanz. 2018, 70, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Mohsin, S.M.; Fujita, M. Quercetin mediated salt tolerance in tomato through the enhancement of plant antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Plants 2019, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rohman, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Monsur, M.B.; Amiruzzaman, M.; Fujita, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Trehalose protects maize plants from salt stress and phosphorus deficiency. Plants 2019, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapoor, R.T.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Exogenous kinetin and putrescine synergistically mitigate salt stress in Luffa acutangula by modulating physiology and antioxidant defense. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 2125–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Lu, B.; Liu, L.; Duan, W.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, H.; et al. Exogenous melatonin improves salt stress adaptation of cotton seedlings by regulating active oxygen metabolism. Peer J. 2020, 8, e10486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, L.; Lin, X.; Sun, C. Hydrogen peroxide alleviates salinity-induced damage through enhancing proline accumulation in wheat seedlings. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, S.M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Hossain, M.S.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Parvin, K.; Fujita, M. Tebuconazole and trifloxystrobin regulate the physiology, antioxidant defense and methylglyoxal detoxification systems in conferring salt stress tolerance in Triticum aestivum L. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.S.; Badawy, A.A.; Osman, A.I.; Latef, A.A.H.A. Ameliorative impact of an extract of the halophyte Arthrocnemum macrostachyum on growth and biochemical parameters of soybean under salinity stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALKahtani, M.; Hafez, Y.; Attia, K.; Al-Ateeq, T.; Ali, M.A.M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Abdelaal, K. Bacillus thuringiensis and silicon modulate antioxidant metabolism and improve the physiological traits to confer salt tolerance in lettuce. Plants 2021, 10, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardus, J.; Hossain, M.S.; Fujita, M. Modulation of the antioxidant defense system by exogenous l-glutamic acid application enhances salt tolerance in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Biomolecules 2021, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Río, L.A.; Corpas, F.J.; López-Huertas, E.; Palma, J.M. Plant superoxide dismutases: Function under abiotic stress conditions. In Antioxidants and Antioxidant Enzymes in Higher Plants; Gupta, D., Palma, J., Corpas, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liebthal, M.; Maynard, D.; Dietz, K.-J. Peroxiredoxins and redox signaling in plants. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bela, K.; Horváth, E.; Gallé, Á.; Szabados, L.; Tari, I.; Csiszár, J. Plant glutathione peroxidases: Emerging role of the antioxidant enzymes in plant development and stress responses. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 176, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xing, X.-J.; Tian, Y.-S.; Peng, R.-H.; Xue, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yao, Q.-H. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing tomato glutathione S-transferase showed enhanced resistance to salt and drought stress. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.R.; Neto, M.C.L.; Carvalho, F.E.; Martins, M.O.; Jardim-Messeder, D.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; Silveira, J.A. Salinity and osmotic stress trigger different antioxidant responses related to cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase knockdown in rice roots. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 131, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, M.; Afzal, S.; Parveen, A.; Kamran, M.; Javed, M.R.; Abbasi, G.H.; Malik, Z.; Riaz, M.; Ahmad, S.; Chattha, M.S.; et al. Silicon mediated improvement in the growth and ion homeostasis by decreasing Na+ uptake in maize (Zea mays L.) cultivars exposed to salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, M.S.; Osman, M.S.; Mohamed, A.S.; Mahgoub, H.A.; Garada, M.O.; Abdelmouty, E.S.; Latef, A.A.H.A. Impact of foliar application of chitosan dissolved in different organic acids on isozymes, protein patterns and physio-biochemical characteristics of tomato grown under salinity stress. Plants 2021, 10, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Pan, R.; Buitrago, S.; Wu, C.; Abou-Elwafa, S.F.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W. Conservation and divergence of the TaSOS1 gene family in salt stress response in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Feng, Z.; Bai, Q.; He, J.; Wang, Y. Melatonin-mediated regulation of growth and antioxidant capacity in salt-tolerant naked oat under salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, F.; Kamal, A.; Singh, A.; Ashfaque, F.; Alamri, S.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Khan, M.I.R. Seed priming with gibberellic acid induces high salinity tolerance in Pisum sativum through antioxidant system, secondary metabolites and upregulation of antiporter genes. Plant Biol. 2020, 23, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.F.A.; Zaid, A.; Latef, A.A.H.A. Salicylic acid spraying-induced resilience strategies against the damaging impacts of drought and/or salinity stress in two varieties of Vicia faba L. seedlings. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, R.S.; Seleiman, M.F.; Shami, A.; Alhammad, B.A.; Mahdi, A.H.A. Integrated application of selenium and silicon enhances growth and anatomical structure, antioxidant defense system and yield of wheat grown in salt-stressed soil. Plants 2021, 10, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Lu, B.; Ma, T.; Jiang, D.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Exogenous melatonin promotes seed germination and osmotic regulation under salt stress in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Beneficial effects of exogenous melatonin on overcoming salt stress in sugar beets (Beta vulgaris L.). Plants 2021, 10, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, M. Antioxidative and proline potentials as a protective mechanism in soybean plants under salinity stress. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 5972–5978. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Golldack, D.; Li, C.; Mohan, H.; Probst, N. Tolerance to drought and salt stress in plants: Unraveling the signaling networks. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurusu, T.; Kuchitsu, K.; Tada, Y. Plant signaling networks involving Ca2+ and Rboh/Nox-mediated ROS production under salinity stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, S.; Waadt, R.; Nuhkat, M.; Kollist, H.; Hedrich, R.; Roelfsema, M.R.G. Calcium signals in guard cells enhance the efficiency by which abscisic acid triggers stomatal closure. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Zhu, J.K. Molecular and genetic aspects of plant responses to osmotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Smith, J.A.; Harberd, N.P.; Jiang, C. The regulatory roles of ethylene and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant salt stress responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 91, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Oku, H.; Nahar, K.; Bhuyan, M.B.; Al Mahmud, J.; Baluska, F.; Fujita, M. Nitric oxide-induced salt stress tolerance in plants: ROS metabolism, signaling, and molecular interactions. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2018, 12, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Khare, T.; Sharma, M.; Wani, S.H. ROS-induced signaling and gene expression in crops under salinity stress. In Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Systems in Plants: Role and Regulation under Abiotic Stress; Khan, M., Khan, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Atia, A.; Barhoumi, Z.; Debez, A.; Hkiri, S.; Abdelly, C.; Smaoui, A.; Haouari, C.C.; Gouia, H. Plant hormones: Potent targets for engineering salinity tolerance in plants. In Salinity Responses and Tolerance in Plants; Kumar, V., Wani, S., Suprasanna, P., Tran, L.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M.; Munné-Bosch, S.; Müller, M. Editorial: Phytohormones and the regulation of stress tolerance in plants: Current status and future directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quamruzzaman, M.; Manik, S.M.N.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M. Improving performance of salt-grown crops by exogenous application of plant growth regulators. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Cho, Y.G. Plant hormones in salt stress tolerance. J. Plant Biol. 2015, 58, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yu, Z.; Gao, L.; Zheng, C. SnRK2s at the crossroads of growth and stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xu, Y.; Jin, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, G.; Huang, J.; Yan, K.; Wu, C.; et al. CEPR2 phosphorylates and accelerates the degradation of PYR/PYLs in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 5457–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabot, C.; Sibole, J.V.; Barceló, J.; Poschenrieder, C. Abscisic acid decreases leaf Na+ exclusion in salt-treated Phaseolus vulgaris L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmani, R.; Bano, A.; Khan, S.U.; Din, J.; Zhang, J.L. Alleviation of salt stress by seed treatment with abscisic acid (ABA), 6-benzylaminopurine (BA) and chlormequat chloride (CCC) optimizes ion and organic matter accumulation and increases yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Aust. J. Crop. Sci. 2011, 5, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, L.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Miao, C.; Hao, F. NADPH oxidase AtrbohD and AtrbohF function in ROS-dependent regulation of Na+/K+ homeostasis in Arabidopsis under salt stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.T.; Chen, Z.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, B.B.; Xi, Z.M. Involvement of ABA and antioxidant system in brassinosteroid-induced water stress tolerance of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.P.; Richa, T.; Kumar, K.; Raghuram, B.; Sinha, A.K. In silico analysis reveals 75 members of mitogen-activated protein kinase gene family in rice. DNA Res. 2010, 17, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lu, S.; Su, W.; Li, H.; Guo, Z. Abscisic acid improves drought tolerance of triploid bermudagrass and involves H2O2- and NO induced antioxidant enzyme activities. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Dietrich, D.; Ng, C.H.; Chan, P.M.; Bhalerao, R.; Bennett, M.J.; Dinneny, J.R. Endodermal ABA signaling promotes lateral root quiescence during salt stress in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Denver, J.B.; Ullah, H. miR393s regulate salt stress response pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana through scaffold protein RACK1A mediated ABA signaling pathways. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019, 14, 1600394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tognetti, V.B.; Bielach, A.; Hrtyan, M. Redox regulation at the site of primary growth: Auxin, cytokinin and ROS crosstalk. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 11, 2586–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.G.; Jung, J.H.; Woo, J.C.; Park, C.M. Integration of auxin and salt signals by the NAC transcription factor NTM2 during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bao, S.; Hua, C.; Shen, L.; Yu, H. New insights into gibberellin signaling in regulating flowering in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magome, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Hanada, A.; Kamiya, Y.; Oda, K. The DDF1 transcriptional activator upregulates expression of a gibberellin-deactivating gene, GA2ox7, under high-salinity stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008, 56, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Mei, Z.; Duan, J.; Chen, H.; Feng, H.; Cai, W. OsGA2ox5, a gibberellin metabolism enzyme, is involved in plant growth, the root gravity response and salt stress. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, N.; Umar, S.; Khan, N.A.; Khan, M.I.R. A new perspective of phytohormones in salinity tolerance: Regulation of proline metabolism. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 100, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, R.; Le, D.T.; Watanabe, Y.; Matsui, A.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tran, L.S. Transcriptome analyses of a salt-tolerant cytokinin-deficient mutant reveal differential regulation of salt stress response by cytokinin deficiency. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshi, R.; Sahoo, K.K.; Tripathi, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, B.K.; Pareek, A.; Singla-Pareek, S.L. Knockdown of an inflorescence meristem-specific cytokinin oxidase–OsCKX2 in rice reduces yield penalty under salinity stress condition. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mähönen, A.P.; Higuchi, M.; Törmäkangas, K.; Miyawaki, K.; Pischke, M.S.; Sussman, M.R.; Helariutta, Y.; Kakimoto, T. Cytokinins regulate a bidirectional phosphorelay network in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tran, L.S.; Urao, T.; Qin, F.; Maruyama, K.; Kakimoto, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Functional analysis of AHK1/ATHK1 and cytokinin receptor histidine kinases in response to abscisic acid, drought, and salt stress in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20623–20628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, W.; Chan, Z.; Wu, Y. Endogenous cytokinin overproduction modulates ROS homeostasis and decreases salt stress resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javid, M.G.; Sorooshzadeh, A.; Moradi, F.; Sanavy, S.A.M.M.; Allahdadi, I. The role of phytohormones in alleviating salt stress in crop plants. Aust. J. Crop. Sci. 2011, 5, 726–734. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhu, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M. Exogenous jasmonic acid can enhance tolerance of wheat seedlings to salt stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 104, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, P.; Li, C.; Xia, G. The moss jasmonate ZIM-domain protein PnJAZ1 confers salinity tolerance via crosstalk with the abscisic acid signalling pathway. Plant Sci. 2019, 280, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakannan, M.; Bose, J.; Babourina, O.; Rengel, Z.; Shabala, S. Salicylic acid improves salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis by restoring membrane potential and preventing salt-induced K+ loss via a GORK channel. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2255–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nazar, R.; Iqbal, N.; Syeed, S.; Khan, N.A. Salicylic acid alleviates decreases in photosynthesis under salt stress by enhancing nitrogen and sulfur assimilation and antioxidant metabolism differentially in two mungbean cultivars. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakannan, M.; Bose, J.; Babourina, O.; Shabala, S.; Massart, A.; Poschenrieder, C.; Rengel, Z. The NPR1-dependent salicylic acid signalling pathway is pivotal for enhanced salt and oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Tayeb, M.A. Response of barley grains to the interactive effect of salinity and salicylic acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2005, 45, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Q.; Qian, R. Salicylic acid promotes plant growth and salt-related gene expression in Dianthus superbus L. (Caryophyllaceae) grown under different salt stress conditions. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 24, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, Z.; Wen, X.; Li, W.; Shi, H.; Yang, L.; Zhu, H.; Guo, H. Salt-induced stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 confers salinity tolerance by deterring ROS accumulation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, T.; Deng, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, L.; Zou, L.; Li, P.; Zhang, D.; Lin, H. Ethylene and hydrogen peroxide are involved in brassinosteroid-induced salt tolerance in tomato. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, L.; Feraru, E.; Feraru, M.I.; Waidmann, S.; Wang, W.; Passaia, G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wabnik, K.; Kleine-Vehn, J. PIN-LIKES coordinate brassinosteroid signaling with nuclear auxin input in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Divi, U.K.; Rahman, T.; Krishna, P. Brassinosteroid-mediated stress tolerance in Arabidopsis shows interaction with absicisic acid, ethylene and salicylic acid pathways. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mishra, P.; Bhoomika, K.; Dubey, R.S. Differential responses of antioxidative defense system to prolonged salinity stress in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive Indica rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. Protoplasma 2013, 250, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossatto, T.; do Amaral, M.N.; Benitez, L.C.; Vighi, I.L.; Braga, E.J.; de Magalhães Júnior, A.M.; Maia, M.A.; da Silva, P.L. Gene expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes in rice plants, cv. BRS AG, under saline stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyagi, S.; Sembi, J.K.; Upadhyay, S.K. Gene architecture and expression analyses provide insights into the role of glutathione peroxidases (GPXs) in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 223, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, K.; Weidner, A.; Surabhi, G.-K.; Börner, A.; Mock, H.-P. Salt stress-induced alterations in the root proteome of barley genotypes with contrasting response towards salinity. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3545–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, R.; Mishra, M.; Gupta, B.; Parsania, C.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A. De novo assembly and characterization of stress transcriptome in a salinity-tolerant variety CS52 of Brassica juncea. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filiz, E.; Ozyigit, I.I.; Saracoglu, I.A.; Uras, M.E.; Sen, U.; Yalcin, B. Abiotic stress-induced regulation of antioxidant genes in different Arabidopsis ecotypes: Microarray data evaluation. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2018, 33, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jing, X.; Hou, P.; Lu, Y.; Deng, S.; Li, N.; Zhao, R.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Lang, T.; et al. Overexpression of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase from mangrove Kandelia candel in tobacco enhances salinity tolerance by the reduction of reactive oxygen species in chloroplast. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Takano, T.; Liu, S. A peroxisomal APX from Puccinellia tenuiflora improves the abiotic stress tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana through decreasing of H2O2 accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 175, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, A.; Pal, A.K.; Sharma, V.; Kalia, S.; Kumar, S.; Ahuja, P.S.; Singh, A.K. Transgenic potato plants overexpressing SOD and APX exhibit enhanced lignification and starch biosynthesis with improved salt stress tolerance. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2017, 35, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb, A.E.; Kawano, N.; Badawi, G.H.; Kaminaka, H.; Sanekata, T.; Shibahara, T.; Inanaga, S.; Tanaka, K. Overexpression of monodehydroascorbate reductase in transgenic tobacco confers enhanced tolerance to ozone, salt and polyethylene glycol stresses. Planta 2007, 225, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Nan, Z.; Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Wang, Z.; Xia, G.; Tian, Y. Synergistic effects of GhSOD1 and GhCAT1 overexpression in cotton chloroplasts on enhancing tolerance to methyl viologen and salt stresses. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Xia, D.; Gao, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, C. Overexpression of a GST gene (ThGSTZ1) from Tamarix hispida improves drought and salinity tolerance by enhancing the ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2014, 117, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Mishra, A.; Jha, B. Ectopic over-expression of peroxisomal ascorbate peroxidase (SbpAPX) gene confers salt stress tolerance in transgenic peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Gene 2014, 547, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, N.P.; Shrivastava, D.C.; Sharma, V.; Sarin, N.B. Overexpression of CuZnSOD from Arachis hypogaea alleviates salinity and drought stress in tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 1109–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Li, Q.; Park, S.C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.G.; Tang, W.; Kou, M.; Ma, D.F. Overexpression of CuZnSOD and APX enhance salt stress tolerance in sweet potato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 109, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Q.; Yanyan, D.; Yuanlin, L.; Kunzhi, L.; Huini, X.; Xudong, S. Overexpression of SlMDHAR in transgenic tobacco increased salt stress tolerance involving S-nitrosylation regulation. Plant Sci. 2020, 299, 110609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.C.; Salvi, P.; Kamble, N.U.; Joshi, P.K.; Majee, M.; Arora, S. Ectopic overexpression of cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase gene (Apx1) improves salinity stress tolerance in Brassica juncea by strengthening antioxidative defense mechanism. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2020, 42, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Species | Level(s) of Salt Stress | Oxidative Damage | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. aestivum cv. Pradip | 150 and 300 mM NaCl; 4 d | Lipid peroxidation increased by 60%. H2O2 level increased by 73%. | [99] |

| B. napus cv. BINA Sharisha 3 | 100 and 200 mM NaCl; 2 d | MDA increased by 69 and 129%. H2O2 incremented by 76 and 90%. | [100] |

| O. sativa cvs. MI-48, IR-28 (salt-sensitive) | 100 mM saline solution (mixture of NaCl, MgCl2, MgSO4 and CaCl2 salts); 35 d | H2O2 and O2•− generation increased by 2-fold. | [101] |

| S. lycopersicum cv. Chibli F1 | 120 mM NaCl; 8 d | Lipid peroxidation elevated by 35 (leaves) and 37% (roots). | [102] |

| O. sativa cv. KDML105 | 60, 120 and 160 mM NaCl; 3 d | H2O2 increased in a dose-dependent manner. | [103] |

| G. max cv. PK9305 | 100 mM NaCl; 7 d | Increment in MDA found in both leaves and roots. Higher activity of LOX in roots. | [104] |

| Phaseolus vulgaris cv. Nebraska | 2.5 and 5.0 dS m−1 (NaCl/CaCl2/MgSO4 = 2:2:1); 40 d | MDA and H2O2 increased with increasing saline concentrations. EL increased, but reduced membrane stability index (MSI). | [105] |

| B. juncea cv. Pusa Jai Kisan | 100 mM NaCl; 30 d | Higher accumulation of H2O2 and thiobarbituric acid reactive species (TBARS). | [106] |

| S. tuberosum cv. Hui 2 | 50, 75 and 100 mM NaCl; 31 d | Elevation in MDA by 164%. | [107] |

| O. sativa cv. BRRI dhan47 | 200 mM NaCl; 3 d | H2O2 increased by 82%. Higher production of MDA. The activity of LOX increased by 78%. | [70] |

| P. vulgaris cvs. Tema (high-yielding) and Djadida (low-yielding) | 50, 100 and 200 mM NaCl; 7 d | Increase in MDA by 44 (cv. Tema) and 56% (cv. Djadida). | [108] |

| O. sativa cv. BRRI dhan47 | 150 mM NaCl; 3, 6 d | MDA increased by 80 (3 d) and 203% (6 d). Increment in H2O2 found, by 74 (3 d) and 92% (6 d). Lipoxygenase (LOX) activity increased by 69 (3 d) and 95% (6 d). | [69] |

| V. radiata cv. BARI Mung-2 | 200 mM NaCl; 2 d | Upregulation of MDA and H2O2. The activity of LOX also increased. | [67] |

| Pisum sativum cv. Shubhra IM-9101 | 100 and 400 mM NaCl; 7 d | Increment in O2•− by 171–407%. H2O2 increased by 191–249%. | [109] |

| T. aestivum cvs. Kharchia local (salt-tolerant) and HD2329 (salt-sensitive) | 10 dS m−1 NaCl; 7 d | EL increased more in cv. HD2329 (by 2.6- and 1.5-fold in the roots and shoots) than Kharchia local (by 1.9- and 1.4-fold in the roots and shoots). Higher accumulation of H2O2 and MDA in sensitive cultivar. | [110] |

| B. juncea cvs. CS-52 (salt-tolerant) and RH-8113 (salt-sensitive) | 50, 100 and 150 mM NaCl; 21 d | MDA generated more in RH-8113 (138%) than CS-52 (126%). H2O2 increased in dose-dependent manner in sensitive cultivar, but at 150 mM NaCl, it increased by 33% in CS-52. | [111] |

| Cicer arietinum cvs. Flip 97-43c (tolerant), ICC 4958 (tolerant), Flip 97-97c (susceptible) and Flip 97-196c (susceptible) | 100 mM NaCl; 3, 7 and 12 d | Accumulation of MDA began to increase after 12 d by 224% in T1 genotype. In S2 genotype, 2.21-, 8.20- and 10.15-fold upregulation of MDA content was found at 3, 7 and 12 d, respectively. | [112] |

| S. lycopersicum cv. Hezuo 903 | 150 mM NaCl; 10 d | Elevation in lipid peroxidation by 2.6-fold. H2O2 increased by 2.5-fold. | [113] |

| B. napus cv. BINA Sharisha 3 | 100 and 200 mM NaCl; 2 d | Gradual increase in MDA by 60–129% in a dose-dependent manner. Production of H2O2 elevated by 63–98%. | [114] |

| S. lycopersicum cv. Pusa Ruby | 150 mM NaCl; 5 d | Elevation in H2O2 and MDA. Increased LOX activity. | [115] |

| Zea mays cvs. BARI hybrid Maize-7 and BARI hybrid Maize-9 | 150 mM NaCl; 15 d | O2•− and H2O2 increased by 130 and 99%. Higher production of MDA by 109%. LOX activity enhanced by 133%. | [116] |

| Luffa acutangula cv. Pusa Sneha | 100 mM NaCl, 10 d | Increase in H2O2, O2•−, EL, MDA and LOX activity by 140, 145, 251, 358 and 157%, respectively. | [117] |

| Gossypium hirsutum | 150 mM NaCl; 3, 6, 9 and 12 d | Increased H2O2 by 58% (3 d), 34% (6 d), 45% (9 d) and 37% (12 d). O2•− incremented by 47% (3 d), 25% (6 d), 37% (9 d) and 32% (12 d). MDA augmented by 25% (3 d), 27% (6 d), 36% (9 d) and 41% (12 d). | [118] |

| T. aestivum | 100 mM NaCl; 1 d | 1.5- and 1.2-fold upregulation of EL and MDA. | [119] |

| T. aestivum cv. Norin 61 | 250 mM NaCl; 5 d | Increase in MDA and H2O2 by 62 and 35%. EL increased by 130%. | [120] |

| G. max cv. Giza 111 | 75 and 150 mM NaCl; 56 d | Level of MDA increased by 47 and 75%. H2O2 augmented by 42 and 50%. | [121] |

| Lactuca sativa cv. SUSANA | 4 dS m−1 (low) and 8 dS m−1 (high) NaCl; 60 d | MDA increased by 44% under low level of NaCl, while increased under high NaCl (70 and 87%) in both seasons. H2O2 augmented by 183 (high) and 166% (low) in both seasons. O2•− increases more at high dose (208 and 262%) in both seasons. | [122] |

| L. culinaris cv. BARI Masur-7 | 110 mM NaCl; 2 d | Content of MDA and H2O2 increased by 164 and 229%. | [123] |

| Plant Species | Level(s) of Salt Stress | Antioxidant Defense | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| G. max cv. A3935 | 50 (low), 100 (medium) and 150 (high) mM NaCl; 30 d | High salinity reduces SOD activity in roots (28%) and leaves (38%). APX activity decreased in leaves by 20% (low) and 57% (high), but slightly increased in roots at low salinity (10%) and decreased by 29% under high salinity. GR and CAT activities decreased in both roots and leaves under high salinity. | [138] |

| T. aestivum cv. Pradip | 150 and 300 mM NaCl; 4 d | AsA content sharply decreased. GSH content and GSH/GSSG ratio increased. Slight increase in APX and GST activities, whereas activities of CAT, DHAR, MDHAR, GR and GPX decreased at 300 mM NaCl stress. | [99] |

| B. napus cv. BINA Sharisha 3 | 100 and 200 mM NaCl; 2d | AsA and GSH content decreased, but GSSG content increased at 200 mM NaCl. GPX, GST and GR activities increased at 100 mM NaCl. Increase in APX activity, and decrease in CAT, DHAR, MDHAR, GR, GST and GPX activities at 200 mM NaCl stress. | [100] |

| O. sativa cv. Pokkali (tolerant) | 100 mM saline solution (mixture of NaCl, MgCl2, MgSO4 and CaCl2 salts); 35 d | Increased activities of SOD, CAT, APX and POX. | [101] |

| O. sativa cv. KDML105 | 60, 120 and 160 mM NaCl; 3 d | SOD, APX and GR activities increase with increasing NaCl concentrations. CAT activity reduced by 1.6-fold at 160 mM NaCl. | [103] |

| G. max cv. PK9305 | 100 mM NaCl; 7 d | Activities of CAT, SOD and PPO observed more in leaves than roots. Higher activity of POX in roots than shoots. | [104] |

| S. tuberosum cv. Hui 2 | 50, 75 and 100 mM NaCl; 31 d | SOD activity increased in a dose-dependent manner. CAT and POD activities decreased at 100 mM NaCl stress, but still higher than non-stressed plants. | [107] |

| O. sativa cv. BRRI dhan47 | 200 mM NaCl; 3 d | AsA content reduced by 49%. Reduction in GSH/GSSG ratio by 42%. The activity of SOD increased by 20%. Reduced CAT activity by 33%. | [70] |

| P. vulgaris cvs. Tema (high-yielding) and Djadida (low-yielding) | 50, 100 and 200 mM NaCl; 7 d | GR activity increased by 60% (Tema) and 20% (Djadida). CAT activity increased by 4- and 2-fold in Tema and Djedida. APX activity increased by 9- and 6- fold in Tema and Djedida. Increment in AsA and total flavonoid content in cv. Tema (by 33 and 47%) and cv. Djadida (by 26 and 70%). Total phenolic compounds decreased markedly in cv. Djadida. | [108] |

| O. sativa cv. BRRI dhan47 | 150 mM NaCl; 3, 6 d | AsA content decreased, but DHA content increased. Higher level of GSH and GSSG content. Upregulation of MDHAR, DHAR and GR activities. APX activity enhanced at 6 d. SOD and GPX activities increased with increasing duration of stress. Reduction in phenolic and flavonoid contents. | [69] |

| V. radiata cv. BARI Mung-2 | 200 mM NaCl; 2 d | Activities of SOD and GST increased by 49 and 88%. CAT activity reduced by 50%. No significant change was observed in GR and GPX activities. Reduction in MDHAR and DHAR activities. | [67] |

| P. sativum cv. Shubhra IM-9101 | 100 and 400 mM NaCl; 7 d | Reduction in CAT (94%), POD (57%) and APX (86%) activities. Increase in SOD activity by 174%. | [109] |

| B. napus cv. BINA Sharisha 3 | 100 (mild) and 200 (severe) mM NaCl; 2 d | AsA content reduced by 44% under severe stress. GSSG content upgraded by 116% under severe stress. APX activity increased, but reduction in MDHAR, DHAR and GR activities. GPX activity reduced under severe stress. The activity of GST enhanced. CAT activity dropped by 32% (mild) and 41% (severe). | [114] |

| S. lycopersicum cv. Pusa Ruby | 150 and 250 mM NaCl; 4 d | Upregulation of SOD activity by 30% (150 mM) and 43% (250 mM). CAT and GR activities decreased. Activities of APX, MDHAR, DHAR, GPX and GST upgraded. AsA content reduced, but DHA content increased. Both GSH and GSSG content upgraded. | [61] |

| G. hirsutum | 150 mM NaCl; 3, 6, 9 and 12 d | SOD activity enhanced by 47, 37, 26 and 18% at 3, 6, 9 and 12 d, respectively. Higher activity of POD found, by 103, 63 and 11% at different durations. CAT activity increased by 28, 20, 14 and 16%. Activity of APX enhanced by 126, 104, 67 and 37% at 3, 6, 9 and 12 d, respectively. | [118] |

| S. lycopersicum cv. Pusa Ruby | 150 mM NaCl; 5 d | AsA content decreased, but DHA increased with ratio lowered by 50%. GSH content reduced, but GSSG content increased with decrease in GSH/GSSG ratio by 45%. Activities of APX, MDHAR, GR, GST and SOD increased by 134, 53, 114, 70 and 16%, respectively. | [56] |

| T. aestivum cv. Norin 61 | 250 mM NaCl; 5 d | Both AsA and AsA/DHA ratio reduced, but DHA content increased. GSSG content increased, but GSH and GSH/GSSG ratio decreased. Activities of APX, DHAR and GPX increased by 29, 38 and 13%, respectively. Reduction in MDHAR (32%), GR (24%), CAT (37%) and GST (15%) activities. | [120] |

| G. max cv. Giza 111 | 75 and 150 mM NaCl; 56 d | Total phenol content notably increased by 24 and 33%. AsA content also enhanced by 32 and 64%. | [121] |

| L. sativa L. cv. SUSANA | 4 dS m−1 (low) and 8 dS m−1 (high) NaCl; 60 d | CAT activity increased by 87 and 89% at low salinity, whereas at high salinity, it increased by 158 and 162% in both seasons. Elevation in POD, and PPO activities increased significantly. | [122] |

| L. culinaris Medik cv. BARI Masur-7 | 110 mM NaCl; 2 d | AsA content reduced by 70%, whereas an increase in GSH (305%) and GSSG (353%) contents was noticed. Reduction in CAT (71%) and APX (41%) activities, while an increase in DHAR (47%), GR (83%) and GPX (162%) activities. | [123] |

| Transgenic Plants | Gene Source | Overexpressed Genes | Salt Stress and Duration | Regulatory Roles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana tabacum | A. thaliana | AtMDAR1 | 300 mM NaCl; 6 d | Improved Pn. Decreased H2O2 content. | [193] |

| G. hirsutum | Agrobacterium tumefaciens | GhSOD1, GhCAT1 | 200 mM NaCl; 2d | Upregulated SOD, CAT and APX activities. Increased oxidative stress tolerance. | [194] |

| A. thaliana | Tamarix hispida | ThGSTZ1 | 75, 100 and 125 mM NaCl; 12 d | Upregulated GST, GPX, SOD and POD activities. Reduced EL and MDA content. | [195] |

| Arachis hypogaea | A. tumefaciens | SbpAPX | 50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 mM NaCl; 21 d | Increased chl content. Improved RWC. Increased plant biomass. Reduced EL. | [196] |

| N. tabacum | A. hypogaea | AhCuZnSOD | 100 mM NaCl; 15 d | Increased RWC. Reduced MDA by 1.5-fold. Decreased H2O2 by 2-fold. Upregulated CAT, GR, APX and SOD activities. | [197] |

| A. thaliana | Puccinellia tenuiflora | PutAPX | 125, 150 and 175 mM NaCl; 3 d | Improved total chl content. Increased RWC. Reduced MDA content. Upregulated APX activity. | [191] |

| Ipomoea batatas | A. tumefaciens | CuZnSOD, APX | 100 mM NaCl; 14 d | Pro content increased by 2.7-fold. SOD and APX activities increased by 3.4- and 4.2-fold. | [198] |

| S. tuberosum | Potentilla atrosanguinea, Rheum australe | PaSOD, RaAPX | 50, 100 and 150 mM NaCl; 15 d | Improved total chl content. Increased RWC. Upregulated SOD and APX activities. | [192] |

| N. tabacum | S. lycopersicum | SlMDHAR | 200 mM NaCl; 5 d | Reduced MDA and H2O2. Reduced Na+ content. | [199] |

| B. juncea | A. tumefaciens | AtApx1 | 200 mM NaCl; 10 d | Increased chl and carotenoid content. Improved Pro content. Decreased MDA and H2O2 content. Increased APX and CAT activities. | [200] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasanuzzaman, M.; Raihan, M.R.H.; Masud, A.A.C.; Rahman, K.; Nowroz, F.; Rahman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179326

Hasanuzzaman M, Raihan MRH, Masud AAC, Rahman K, Nowroz F, Rahman M, Nahar K, Fujita M. Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Salinity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(17):9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179326

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasanuzzaman, Mirza, Md. Rakib Hossain Raihan, Abdul Awal Chowdhury Masud, Khussboo Rahman, Farzana Nowroz, Mira Rahman, Kamrun Nahar, and Masayuki Fujita. 2021. "Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Salinity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 17: 9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179326

APA StyleHasanuzzaman, M., Raihan, M. R. H., Masud, A. A. C., Rahman, K., Nowroz, F., Rahman, M., Nahar, K., & Fujita, M. (2021). Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Salinity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(17), 9326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22179326