Abstract

The human microbiome plays a crucial role in determining the health status of every human being, and the microbiome of the genital tract can affect the fertility potential before and during assisted reproductive treatments (ARTs). This review aims to identify and appraise studies investigating the correlation of genital microbiome to infertility. Publications up to February 2021 were identified by searching the electronic databases PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus and Embase and bibliographies. Only full-text original research articles written in English were considered eligible for analysis, whereas reviews, editorials, opinions or letters, case studies, conference papers, and abstracts were excluded. Twenty-six articles were identified. The oldest studies adopted the exclusive culture-based technique, while in recent years PCR and RNA sequencing based on 16S rRNA were the most used technique. Regardless of the anatomical site under investigation, the Lactobacillus-dominated flora seems to play a pivotal role in determining fertility, and in particular Lactobacillus crispatus showed a central role. Nonetheless, the presence of pathogens in the genital tract, such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Gardnerella vaginalis, Ureaplasma species, and Gram-negative stains microorganism, affected fertility also in case of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis (BV). We failed to identify descriptive or comparative studies regarding tubal microbiome. The microbiome of the genital tract plays a pivotal role in fertility, also in case of ARTs. The standardization of the sampling methods and investigations approaches is warranted to stratify the fertility potential and its subsequent treatment. Prospective tubal microbiome studies are warranted.

1. Introduction

The human microbiome plays a significant role in determining the health status of every human body and in fact, bacterial communities coexist in mutualistic symbiotic relationships with the host [1,2,3]. The term microbiome was originally defined by Whipps et al. [4] as “a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably well-defined habitat which has distinct physio-chemical properties” and today, this definition, is enriched by a dynamic consideration of the microbial activities that result in ecological niches [5]. Variation of the composition of the microbiome can lead to a state of dysbiosis, particularly in case of stress conditions, where the rapid decrease of microbial diversity promotes the expansion of specific bacterial or pathogens [6]. Traditionally, microbiome studies were conducted with culture-based methods that were used to identify bacterial species, but nowadays the introduction of high-throughput DNA sequencing has overcome the limit of the aforementioned approach. In fact, cultured-based methods are still informative, but they only detect a small proportion of organisms that are not representative of the ecological niche under investigation [7]. Similarly, optical magnification techniques have also been used to identify bacteria based on phenotype or morphological details, but today the preferred methods for investigation are sequencing technologies with taxonomy-associated markers genes, such as the 16S rRNA or whole genome sequences [8].

In recent years, the microbiota of various anatomical sites, such as the gastrointestinal (GI) and urogenital tracts, have been investigated, and notably, it was found that the GI tract accounts up to 29% of the whole human microbiome, while the urogenital tract contributes up to 9% [9]. A paradigmatic example is the human vaginal microbiome that is an important site of symbiosis where lactobacilli dominate the microbial community and help defend women against infectious disease, hence playing a potential pivotal role in reproductive outcomes, such as fertility and gestational length [9]. Nonetheless, the vaginal microbiome of the mother has an essential well-known role in the initial colonization of the newborn, which impacts their immune system and neurodevelopment [10].

The aim of this systematic review is to report the current evidence regarding the relationship between genital female microbiome and fertility issue and eventual potential implication on assisted reproductive treatments (ARTs).

2. Materials and Methods

The literature search for articles regarding microbiota/microbiome/microfilm/microflora and fertility or infertility was performed using three following databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Embase. The search strategy was properly adapted to each database. Moreover, the authors hand-searched the references of the eligible studies in order to obtain a full view on the topic. Details on the search strategy are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy for used databases.

The last search was performed on February 2021 and there were no restrictions on the date of publication. This study aimed to ask the following PICOS questions:

- -

- Population: women or couples with infertility (any type) or non-pregnant condition.

- -

- Intervention: genital tract microbial assessment

- -

- Comparison: optional comparison with microbiome of fertile women.

- -

- Outcomes: composition of the microbial flora correlated with infertility or ARTs failure

- -

- Study design: only full-text original research articles written in English were considered eligible for analysis, whereas reviews, editorials, opinions or letters, case studies, conference papers, and abstracts were excluded.

This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. No Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was required for this study.

3. Results

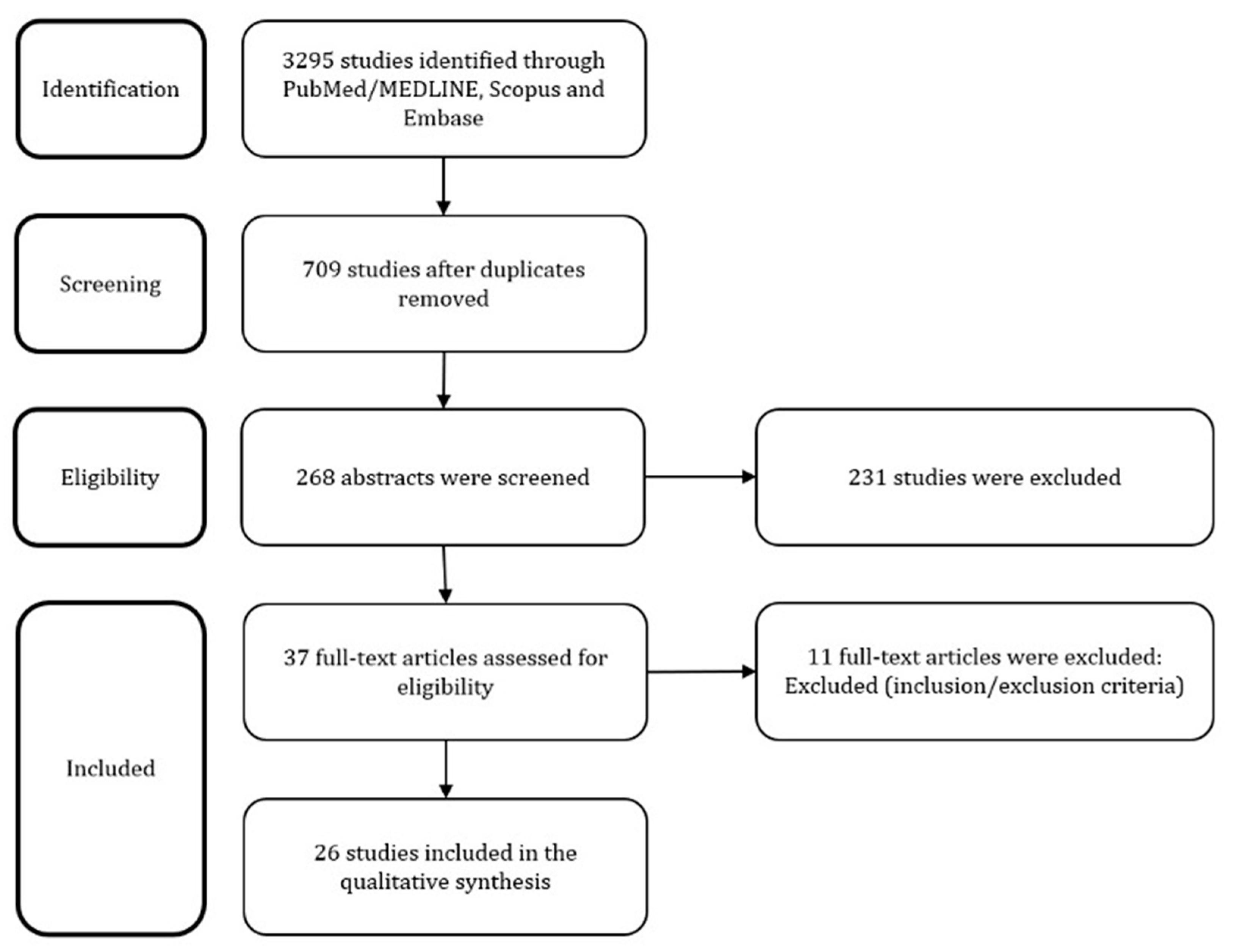

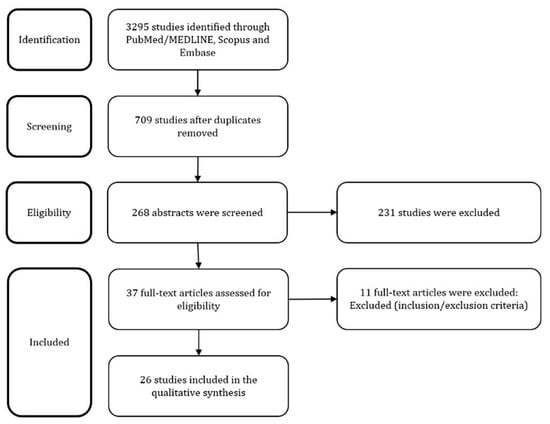

The above described search strategy retrieved 3295 articles. After deletion of duplicates and careful overview of the abstracts and full-texts if needed, 20 articles were selected. Moreover, 6 additional articles were found during the hand-searching of its references. Finally, 26 articles that constituted the final pool were discussed in the following paragraphs. The study selection process is reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

We briefly introduced the sampling and analyses methods and subsequently discussed the findings mainly based on the principal anatomical site under investigation that produces relevant results in every study. A synoptic overview was reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Synoptic overview of the articles included in the review.

4. Discussions

In this review, we took into account the relevant literature regarding genital tract microbiome and its potential impact on fertility. According to our review, the majority of data suggests a not negligible role of the genital microbiome in infertile women and dysbiosis and the lack of Lactobacilli can eventually impair ARTs outcomes. The evaluation of the genital microbiome is not yet standardized nor systematically implemented in any guidelines.

4.1. Sampling Methods

The first experiences of microbiome assessment in infertile women were performed with classical methods, such as either vaginal or cervical swabs [13]. The most important steps to be considered are to avoid bacterial contamination, and to sample the exact anatomical site subject of the investigation. Samples can be collected using different sets of swabs, tube, or buffer solution and the sampling can be performed by a trained professional or self-collected. The need of adherence to a strict protocol is of paramount importance to correctly reach the anatomical site without contamination by surroundings ecological niches [9]. The storage of the specimen is also a crucial step that need careful attention until subsequent processing; further, a prompt investigation can decrease the risk of contamination or bacterial overgrowth.

4.2. Methods of Analysis

Classical analysis consists of culture-dependant methods; in fact, after a certain period of culturing, different bacterial species can be identified using characteristics cell staining, morphology or observed biochemical reactions [12,14]. Culture-based methods are time-consuming and can provide information only regarding bacteria whose metabolic substrates are provided by the culture terrain. Based on that, it is clear how the main limitation is the lack of a complete and representative scenario of the ecological niche under investigation.

Classification based on gram staining and cell morphology is possible using microscopy of clinical specimens, and today this method is still adopted to identify the clue cell or to assess the Nugent Score in genital microbiome samples. However, this technique is time-consuming and requires not-negligible know-how and training [37].

Over the past decade, there has been an explosion of interest in molecular-based, culture-independent techniques to study the microbiome, and sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) related genes largely changed the approach to study the microbiome [38]. In fact, 16S rRNA is a component of the 30S small subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome and the genes coding for this component are used to reconstruct phylogenies, due to their slow rates of genomic evolution. The more the sequences of 16S rRNA genes of different bacteria match, the more likely the microbes are related at a higher taxonomic rank; for example, the threshold sequence identity is 94.5% for genera and 86.5% for families [16].

The quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is a sensitive method to identify a specific group of bacteria and is a well-established tool for detection, quantification, and typing of different microbial species [39]. qPCR can be used to identify pathogens through the design of an ad-hoc assay that provides fast and high-throughput detection and quantification of target DNA sequences. The main limitation of this technique is the knowledge of gene sequencing of the pathogen under investigation.

After the introduction of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, massive parallelisation of bacterial sequencing of 16S rRNA was possible in combination with bioinformatics pipelines that provided final clustering of the results according to similarity concepts; currently, 99% is proposed as the optimal threshold for similarity to correctly assign a taxonomic unit [29]. The whole genome sequencing (WGS) approach is another interesting opportunity to study not only the sequences of interest, but all the bacterial genomes, the function of the different genes, and to identify novel genes, pathways, structure and organization of genomes [8].

Finally, another method adopted to study microbiomes is the intergenic spaces (IS)-pro technique, which is another amplification approach on the IS regions, whose lengths are specific for each group of bacteria [40]. IS-pro technique is a new qPCR-based profiling technique for high-throughput analysis of the human intestinal microbiota, which combines bacterial species recognition based on the length of the 16S–23S rDNA interspace region with taxonomic classification by labelling PCR primers to phylum-specific fluorescent sequences [41].

4.3. Vaginal Findings

The majority of evidence derives from the assessment of vaginal microbiome, that is the easiest anatomical site to sample. The proof of concept of all the studies performed is to identify those patients with an abnormal vaginal microbiome and highlight the differences related to successful ARTs or pregnancy success. The paradigmatic study with culture-based technique is an Indian study, where the vaginal flora of infertile patients was assessed by routine aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal culture with the aim to detect asymptomatic vaginosis and to compare the vaginal microbiota of infertile women versus healthy women. The authors found a prevalence of 28% of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis (detected by associated pathogens such as Candida, Enterococcus, and Escherichia coli) in infertile patients and, when compared to healthy women, a pronounced lower rate of Lactobacillus colonies [28].

Beside a culture-based approach, the diagnostic performance of qPCR for abnormal microbiome compared to Nugent Score criteria in infertile women was firstly assessed by Haarhr et al. [24] in 130 women. qPCR analysis found an abnormal microbiota in 28% of the population, while Nugent Score detected 21% of patients affected by bacterial vaginosis (BV). Of interest, the sensitivity and specificity of qPCR was both 93% in Nugent-defined BV and only 9% of patients with abnormal microbiota obtained a clinical pregnancy. Similarly, using non culture-based methods, the study of Bernabeu et al. [33] identified different clusters of vaginal microbiome in women with recurrent implantation failure, and precisely a cluster predominated by Lactobacillus is associated with the achievement of pregnancy after embryo transfer. On the other hand, a higher rate of Gardnerella vaginalis and lower rate of Lactobacillus species were correlated with a worse outcome. Again, also the vaginal microbiome profiling with IS-pro technique detected a low load of Lactobacillus, and further a high load of Proteobacteria or Lactobacillus jenseni in those women with failure of pregnancy in a group of 192 women underwent ARTs [32]. Moreover, this technique highlighted two different profiles for Gardnerella vaginalis, but only one of these was correlated with low pregnancy rate and overall, only 6% of the women affected by the previous conditions became pregnant after an embryo transfer. Curiously, the high abundance of Lactobacillus crispatus (greater than 60%) was correlated with a worse outcome of ARTs and hence generalization regarding the possible beneficial effects of Lactobacilli on fertility should be avoided, given that different species of the latter may differently affect ART outcomes. Campisciano et al. [21] adopted the NGS approach to compare the vaginal microbiome of idiopathic and non-idiopathic infertile women, healthy women, and women affected by BV with the aim to detect suitable biomarkers for infertility. The vaginal microbiome of idiopathic infertile women was similar to BV-associated microbiome. Furthermore, Lactobacillus iners resulted as a marker of healthy vaginal microbiome, while Lactobacillus crispatus levels were lower in idiopathic infertile women when compared to healthy women and these findings is only partially in contrast to the previous study. In fact, on one hand, the drop of Lactobacillus crispatus may lead to an increased susceptibility to pathogens, hence favouring BV; on the other hand, the simple presence of the latter is not a favourable factor, but the degree of domination of Lactobacillus crispatus in the vaginal microbiome is probably the key of lecture.

An interesting study by Borovkova et al. [18] clarified the influence of the sexual intercourse on the genital tract microbiome of infertile couples. The study protocol was based on PCR analysis of self-collected vaginal samples taken 3–5 days before and 8–12 h after intercourse and semen samples collected during the subsequent menstrual period of the partner. Ureaplasma parvum was found in 59% of women and its prevalence was higher in women whose partners had inflammatory prostatitis; nonetheless, the same pathogen was found in half of the male partners. After intercourse, a median of four and two new species emerged, respectively, and disappeared in women, and the authors noted that these changes were less frequent in the presence of a normal vaginal microbiota and more prominent in the partners of men affected by inflammatory prostatitis, arguing that this microbial shifting can interfere with fertilization.

The embryo implantation rate was not significantly decreased by the presence of BV in a study of 307 women who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF), whose vaginal microbiome was investigated with a validated diagnostic test by qPCR using sterile cytobrush and cotton swabs [19]. In this study, the overall prevalence of BV was 9%, with a greater prevalence (22%) in those who performed vaginal douching. Not only was the rate of embryo implantation similar, but the clinical pregnancy rate was also not statistically different, and no differences were noted in terms of worse obstetric outcomes, so the authors can only conclude that the only advise for women is to not perform vaginal douching.

4.4. Cervical Findings

One of the first studies [13] describing the normal flora of the cervix of different populations of women, respectively infertile, pregnant, and in labour patients found no difference in the distribution of the bacterial species; however, in infertile women, the authors reported the lowest proportion of both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and further, exclusive anaerobic flora was found in more than half of the group of infertile women, indicating that the human cervix flora should be regarded as a complex of interacting and competing bacteria. Previously, Hok et al. [12] reported similar findings, affirming that Mycobacterium tuberculosis was the only one with a higher occurrence in infertile patients; again, bacterial culturing [14] on cervical swabs, performed for cervicitis, failed to show different cervical flora in infertile women, even though 16% of these women were found positive for Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies on the serum. A further confirmation derived from the study of Cheong et al. [36] that assessed the prevalence of the aforementioned pathogen using rRNA metagenomic sequencing on endocervical swabs and found that the large majority of infertile women was infected with Chlamydia trachomatis, in contrast with a lower prevalence of the infection in the fertile group of women (88% vs. 28%) after correction of the results according to demographics parameters. Moreover, many further associated pathogens were isolated more frequently in those women with Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Given the evidence that Chlamydia trachomatis is linked with infertility, Graspeuntetner et al. [27] adopted 16S rRNA sequencing on cervical specimen and parallelly investigated the presence of anti-Chlamydia antibodies in patients with infectious infertility, non-infectious infertility and healthy volunteers. A higher rate of Chlamydia trachomatis was observed in infectious infertility women when compared to non-infectious group, while a progressive decrement of Lactobacillus species was detected in healthy volunteers, non-infectious, and infectious infertility women (78.3%, 69%, and 58%), respectively; on the contrary, Gardnerella vaginalis was seen with an increasing trend in the same groups (5%, 6%, and 10%) and a similar trend was observed also for Prevotella and Sneathia.

Bacteria culturing of cervical canal swab performed before embryo transfer in 204 women demonstrated a significant correlation between the presence of any gram negative colonization and the failure of conception; notably, women with sterile cervical culture or demonstrating Lactobacillus had a higher chance of getting pregnant [17]. Similarly, a French study [16] instead assessed the bacteriology state of the catheter tip used as an endocervical probe before embryo transfer in 279 infertile women underwent IVF and correlated the results with successful clinical pregnancies. In the women with positive culture, the authors registered a predominance of Escherichia coli and streptococcus species with clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates and implantation rates significantly lower when compared to women with negative culture (24% versus 37%; 17% versus 28%; and 9% versus 16%, respectively).

4.5. Endometrial Findings

The first study assessing the microbiome of the endometrium in infertile women was conducted by Ilesanmi et al. [15] with a culture-dependent analysis based on endometrial samples collected with sterile precautions. None of the cultures of endometrial biopsy specimens yielded any growth and the Gram stains were all negative, both for organisms and pus cells and hence authors concluded that this practice is not useful for this clinical scenario. Conversely, an explorative study [22] on 19 non pregnant-women, including those affected by sub-fertility condition, adopted PCR analysis and RNA sequencing to investigate the putative presence of uterine microbiome and found that 90% of the patients had a predominant presence of Bacteroides and Pelomonas taxa, and in a few cases, they noted the presence of Lactobacillus crispatus and Iners associated more frequently with Bacterioides species. Moreno et al. [23] demonstrated in women undergoing IVF the existence of an endometrial microbiota that is highly stable during the acquisition of endometrial receptivity, but differently associated with adverse reproductive outcomes based on its composition. In their study, the authors compared the results of 16S rRNA analysis of paired samples of endometrial fluid and vaginal aspirates in pre-receptive and receptive phases within the same menstrual cycle and correlated them with the reproductivity outcomes. Regardless of hormonal status, the comparison with the vaginal microbiota demonstrated that the endometrial microbiota is not a carryover from the vagina, because some bacterial genera present in the endometrium were not in the vagina of the same subject, and vice versa. This approach permitted identification of the existence of vaginal and endometrial bacterial communities that are not identical in every woman. The endometrial microbiota with a non-Lactobacillus-dominated flora (<90% of Lactobacillus species with >10% of other bacteria) was associated with decreased implantation, pregnancy, ongoing pregnancy, and live birth rates. The authors suggested that the lack of Lactobacillus-dominated flora can be considered as an emerging cause of implantation failure and pregnancy loss. A subsequent pilot study conducted in 102 infertile Japanese women [30] assessed and compared the endometrial versus vaginal microbiota by 16S rRNA sequencing. The authors included healthy volunteers as the control group, which allowed them to demonstrate a high stable rate of Lactobacilli both in endometrial and vaginal samples and also in the following cycle, confirming that Lactobacillus-dominated flora is independent of hormonal changes during the fertile period. The authors investigated the endometrial versus vaginal microbiome of different groups of patients, finding rates of Lactobacillus-dominated flora of 38% (30/79) versus 44.3% (44/79), respectively, in IVF patients, and 73.9% (17/23) vs. 73.9% (17/23) in the non-IVF patients. Considering the percentage of abnormalities in the microbiome of IVF patients, compared to the non-IVF patients or healthy volunteers, the authors believed that endometrial microbiome might be related to unexplained recurrent implant failures. Another comparative study [35], characterized by qPCR analysis the endometrial fluid and vaginal microbiome in infertile women affected by recurrent implant failures (RIF) versus those undergoing their first IVF attempt. No differences among endometrial and vaginal microbiome in the detection of specific bacterial species within the same individual were detected; however, endometrial microbiome presented a higher degree of microbial diversity when compared to its vaginal counterpart. Surprisingly, Lactobacillus-dominated flora was seen more frequently in the RIF group, than in the control group, although without significant statistical difference, both in the endometrial fluid and vaginal samples. Gardnerella Vaginalis was detected more frequently in endometrial fluid of the RIF group, even though without statistical significance; noteworthy, Burkholderia was detected in 25% of the RIF group and none in the control group. A great limitation of this study is the unpredictable longitudinal RIF in the control group, making the results less generalizable. A study by Liu et al. [34] systematically compared the endometrial microbiota in 130 infertile women with and without chronic endometritis (CE), diagnosed by sequencing of 16S rRNA. CE was associated with a statistically significant higher abundance of 18 bacterial taxa in the endometrial cavity; relative abundance of Lactobacillus was greater in non-CE patients (1.89% vs. 80.7%) with a less abundance of Lactobacillus crispatus in the CE group of patients while Anaerococcus and Gardnerella were negatively correlated with the relative abundance of Lactobacillus in CE microbiome.

4.6. Miscellanea Findings

An Indian study by Mishra et al. [26] included 288 infertile couples, performing either cervical or high vaginal swab and semen samples for culture analyses. A high prevalence of Escherichia coli was implicated in primary infertility, even though it was not the only isolated pathogen; hence, the authors suggested adopting therapeutic managements strategies of couples with primary infertility such as antibiotics and a parallel treatment to avoid cross-retransmission. A pilot study by Wee et al. [31] compared the microbiome of the vagina, the cervix, and endometrium of infertile women in comparison to those of women with a history of fertility, using 16S rRNA amplification, moreover, they conducted an ancillary investigation into the endometrial expression of selected genes using PCR analysis. Lactobacillus genus was the most frequently observed overall and the abundance of taxonomic units was the same both in cervical and vaginal specimens; the dominant microbiome was consistent also in regards to the endometrium, even though in different relative proportions. There was a trend for infertile women that demonstrated Ureaplasma in the vagina and Gardnerella in the cervix. The test for the expression of selected genes in the endometrium failed to show any correlations with case–control status, or with microbial community composition, although Tenascin-C expression was correlated with a history of miscarriage.

Pelzer et al. [20] compared the microbiome of human follicular fluid of 202 infertile women with vaginal sample counterparts using culturing and PCR analysis. They found that the presence of Lactobacillus species in human follicular fluid was associated with embryo maturation and transfer, and conversely the presence of contaminants (bacteria detected also in the matched vaginal sample) affected adversely the IVF outcomes without however identifying a single species associated with decreased fertilization rates.

Notably, a couple of studies included in our review undertook both RNA sequencing on the distal part of the catheter used for embryo transfer [25] and one of them also added a PCR analysis [29]. In their analysis, the studies failed to detect a difference in the prevalence of Lactobacilli and lactic acid-producing bacteria among women with ongoing pregnancy against who did not have a pregnancy. These couple of studies represent a proof of concept for the characterization of the microbiome at the time of embryo transfer and could potentially be prospectively employed to understand the need of probiotics in a subsequent successful pregnancy event.

5. Conclusions

The available data suggest a not negligible role of the genital microbiome in infertile women and further, dysbiosis and the lack of Lactobacilli can potentially impair ARTs and partially explain implantation failures. A complex interaction of the Lactobacillus species plays a pivotal role for the equilibrium of the normal vaginal flora and in particular appropriate levels of Lactobacillus crispatus are involved as protective factor for asymptomatic BV (mostly sustained by Ureaplasma and Gardnerella vaginalis) that is recognized as a potential impairing factor of fertility. Similarly, the presence in the cervical flora of Gram-negative bacteria, Chlamydia trachomatis and Gardnerella vaginalis, and the eventual coexistent lack of Lactobacillus is linked with infertility condition. The lack of a Lactobacillus-dominated flora in the endometrium seems linked with recurrent implant failures, and the latter is supported by the prevalence of Bacteroides species in the endometrium of non-pregnant women, given the fact that hormonal changes do not impact the variety of endometrial microbiome, including the relative abundance of Lactobacilli. Of note, Gardnerella vaginalis was also isolated in the endometrium of infertile women. Embryo transfer seems not influenced by vaginal dysbiosis, even though the strength of this affirmation is very weak, whereas the success of the embryo transfer is conversely impacted by abnormal cervical flora.

Another point of discussion is the total lack of data regarding microbiome of the tube(s); in fact, we failed to identify studies investigating this anatomical site. Of course, we believe that the sampling of the tube is a more invasive procedure that cannot be performed as easily as a vaginal swab, even though an outpatient procedure with an in-office hysteroscope might be feasible and well tolerated by the woman. In literature, we found examples of brush cytology of the fallopian tube [42,43,44] using minimally invasive hysteroscopes [45,46,47,48,49], even though in the setting of prevention of ovarian cancer [43,45]. A previously reported study [20] investigated the contamination of follicular fluid by vaginal pathogens, hence, providing the rational for tubal microbiome sampling in infertile women. Similarly, comparative microbiome studies of the different anatomical sites of the genital tract, namely vagina, cervix, endometrium, tube(s), and follicular fluid with 16S rRNA analyses can represent an exciting unexplored field of research [46,50].

Microbiome profiling requires international consensus regarding sampling and investigation analyses that should be performed without culture-dependent methods, and large prospective studies with homogeneous inclusion and exclusion criteria are needed to explore this field with a robust clinical and translational outlook.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G.V. and M.C.; methodology, data curation, P.D.F. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C., G.R. and A.M.C.R.; writing—review and editing, F.F., G.M.V., M.Z. and A.P.; supervision, F.F. and S.C.; project administration, S.C. and G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was not supported by any fund/grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent is not required for this type of study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the reference 50. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Davenport, E.R.; Sanders, J.G.; Song, S.J.; Amato, K.R.; Clark, A.G.; Knight, R. The human microbiome in evolution. BMC Biol. 2017, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, R.; Callewaert, C.; Marotz, C.; Hyde, E.R.; Debelius, J.; McDonald, D.; Sogin, M.L. The Microbiome and Human Biology. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2017, 18, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruvada, P.; Leone, V.; Kaplan, L.M.; Chang, E.B. The human microbiome and obesity: Moving beyond associations. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipps, J.M.; Lewis, K.; Cooke, R.C. Mycoparasitism and plant disease control 161–187. In Fungi in Biological Control Systems; Burge, N.M., Ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1988; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, S.L. History of medicine: Origin of the term microbiome and why it matters. Hum. Microbiome J. 2017, 4, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, P.; Rosa, L.; Capobianco, D.; Lepanto, M.S.; Schiavi, E.; Cutone, A.; Paesano, R.; Mastromarino, P. Role of lactobacilli and lactoferrin in the mucosal cervicovaginal defense. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, I.; Simon, C. Relevance of assessing the uterine microbiota in infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagini, F.; Greub, G. Bacterial genome sequencing in clinical microbiology: A pathogen-oriented review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2007–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, L.M.; Creasy, H.H.; Fettweis, J.M. The integrative human microbiome project. Nature 2019, 569, 641–648. [Google Scholar]

- Buchta, V. Vaginal microbiome. Ces. Gynekol. 2018, 83, 371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hok, T. Comparative endocervical bacteriology of the mucus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1967, 98, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, P.; Eneroth, P.; Harlin, J.; Ljung-wadstrm, A.; Nord, C. Cervical bacterial flora in infertile and pregnant women. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1978, 165, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskimies, A.; Paavonen, J.; Meyer, B.; Kajanoja, P. Cervicitis and infertility. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1981, 1, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Ilesanmi, O.A.; Edozien, L.C. Culture of the endometrium of infertile women culture of the endometrium of infertile women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1995, 15, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fanchin, R.; Harmas, A.; Benaoudia, F.; Lundkvist, U.; Olivennes, F.; Frydman, R. Microbial flora of the cervix assessed at the time of embryo transfer adversely affects in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil. Steril. 1998, 70, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, R.; Ben-Shlomo, I.; Colodner, R.; Keness, Y.; Shalev, E. Bacterial colonization of the uterine cervix and success rate in assisted reproduction: Results of a prospective survey. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovkova, N.; Korrovits, P.; Ausmees, K.; Türk, S.; Jõers, K.; Punab, M.; Mändar, R. Anaerobe in fluence of sexual intercourse on genital tract microbiota in infertile couples. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangot-Bertrand, J.; Fenollar, F.; Bretelle, F.; Gamerre, M.; Raoult, D.; Courbiere, B. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis: Impact on IVF outcome. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 32, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelzer, E.S.; Allan, J.A.; Waterhouse, M.A.; Ross, T.; Beagley, K.W.; Knox, C.L. Microorganisms within human follicular fluid: Effects on IVF. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisciano, G.; Florian, F.; D’Eustacchio, A.; Stanković, D.; Ricci, G.; De Seta, F.; Comar, M. Subclinical alteration of the cervical-vaginal microbiome in women with idiopathic infertility. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraelen, H.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Desimpel, F.; Jauregui, R.; Vankeirsbilck, N.; Weyers, S.; Verhelst, R.; De Sutter, P.; Pieper, D.H.; Van De Wiele, T. Characterisation of the human uterine microbiome in non-pregnant women through deep sequencing of the V1-2 region of the 16S rRNA gene. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, I.; Codoñer, F.M.; Vilella, F.; Valbuena, D.; Martinez-Blanch, J.F.; Jimenez-Almazán, J.; Alonso, R.; Alamá, P.; Remohí, J.; Pellicer, A.; et al. Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haahr, T.; Jensen, J.; Thomsen, L.; Duus, L.; Rygaard, K.; Humaidan, P. Abnormal vaginal microbiota may be associated with poor reproductive outcomes: A prospective study in IVF patients. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franasiak, J.M.; Werner, M.D.; Juneau, C.R.; Tao, X.; Landis, J.; Zhan, Y.; Treff, N.R.; Scott, R.T. Endometrial microbiome at the time of embryo transfer: Next-generation sequencing of the 16S ribosomal subunit. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2016, 33, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, M.C.; Mishra, S.P.; Panda, R.; Patnaik, T. Surveillance of microbial flora for infertility couples in an indian tertiary care teaching hospital. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Graspeuntner, S.; Bohlmann, M.K.; Gillmann, K.; Speer, R.; Kuenzel, S.; Mark, H.; Hoellen, F.; Lettau, R.; Griesinger, G.; König, I.; et al. Microbiota-based analysis reveals specific bacterial traits and a novel strategy for the diagnosis of infectious infertility. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, G.; Singaravelu, B.; Srikumar, R.; Reddy, S.V. Comparative study on the vaginal flora and incidence of asymptomatic vaginosis among healthy women and in women with infertility problems of reproductive age. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Franasiak, J.M.; Zhan, Y.; Scott, R.T.; Rajchel, J.; Bedard, J.; Newby, R.; Treff, N.R.; Chu, T. Characterizing the endometrial microbiome by analyzing the ultra-low bacteria from embryo transfer catheter tips in IVF cycles: Next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis of the 16S ribosomal gene. Hum. Microbiome J. 2017, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyono, K.; Hashimoto, T.; Nagai, Y.; Sakuraba, Y. Analysis of endometrial microbiota by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing among infertile patients: A single-center pilot study. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2018, 17, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, B.A.; Thomas, M.; Sweeney, E.L.; Frentiu, F.D.; Samios, M.; Ravel, J.; Gajer, P.; Myers, G.; Timms, P.; Allan, J.A.; et al. A retrospective pilot study to determine whether the reproductive tract microbiota differs between women with a history of infertility and fertile women. Aust. NZ J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 58, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koedooder, R.; Singer, M.; Schoenmakers, S. The vaginal microbiome as a predictor for outcome of in vitro fertilization with or without intracytoplasmic sperm injection: A prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1042–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabeu, A.; Lledo, B.; Díaz, M.C.; Lozano, F.M.; Ruiz, V.; Fuentes, A.; Lopez-Pineda, A.; Moliner, B.; Castillo, J.C.; Ortiz, J.A.; et al. Effect of the vaginal microbiome on the pregnancy rate in women receiving assisted reproductive treatment. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ko, E.Y.-L.; Wong, K.K.-W.; Chen, X.; Cheung, W.-C.; Law, T.S.-M.; Chung, J.; Tsui, S.K.-W.; Li, T.C.; Chim, S.S.-C. Endometrial microbiota in infertile women with and without chronic endometritis as diagnosed using a quantitative and reference range-based method. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 707–717.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaya, K.; Nagai, Y.; Arai, W.; Sakuraba, Y.; Ishikawa, T. Characterization of Microbiota in Endometrial Fluid and Vaginal Secretions in Infertile Women with Repeated Implantation Failure. Mediat. Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, H.C.; Yap, P.S.X.; Chong, C.W.; Cheok, Y.Y.; Lee, C.Y.Q.; Tan, G.M.Y.; Sulaiman, S.; Hassan, J.; Sabet, N.S.; Looi, C.Y.; et al. Diversity of endocervical microbiota associated with genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection and infertility among women visiting obstetrics and gynecology clinics in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.; Peirano, G.; Lloyd, T.; Read, R.; Carter, J.; Chu, A.; Shaman, J.A.; Jarvis, J.P.; Diamond, E.; Ijaz, U.Z.; et al. Molecular diagnosis of vaginitis: Comparing quantitative pcr and microbiome profiling approaches to current microscopy scoring. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarza, P.; Yilmaz, P.; Pruesse, E.; Glöckner, F.O.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.-H.; Whitman, W.; Euzéby, J.; Amann, R.; Rossello-Mora, R. Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, P.; Ricchi, M. A basic guide to real time pcr in microbial diagnostics: Definitions, parameters, and everything. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, G.M. Genomic approaches to studying the human microbiota. Nature 2012, 489, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budding, A.E.; Grasman, M.E.; Lin, F. IS-pro: High-throughput molecular fingerprinting of the intestinal microbiota. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 4556–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, D.; Guido, R.; Rodriguez, E.; Lee, T.; Mansuria, S.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Austin, R.M. Brush Cytology of the Fallopian Tube and Implications in Ovarian Cancer Screening. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014, 21, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Török, P.; Molnár, S.; Herman, T.; Jashanjeet, S.; Lampé, R.; Riemma, G.; Vitale, S.G. Fallopian tubal obstruction is associated with increased pain experienced during office hysteroscopy: A retrospective study. Updat. Surg. 2020, 72, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messalli, E.M.; Grauso, F.; Balbi, G.; Napolitano, A.; Seguino, E.; Torella, M. Borderline ovarian tumors: Features and controversial aspects. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 167, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizzo, S.; Noventa, M.; Quaranta, M.; Vitagliano, A.; Saccardi, C.; Litta, P.; Antona, D. A Novel Hysteroscopic Approach for Ovarian Cancer Screening/Early Diagnosis [Internet] Oncology Letters; Spandidos Publications: Athens, Greece, 2017; Volume 13, pp. 549–553. [Google Scholar]

- Giampaolino, P.; Foreste, V.; Di Filippo, C.; Gallo, A.; Mercorio, A.; Serafino, P.; Improda, F.; Verrazzo, P.; Zara, G.; Buonfantino, C.; et al. Microbiome and PCOS: State-Of-Art and Future Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiofalo, B.; Palmara, V.; Vilos, G.A.; Pacheco, L.A.; Lasmar, R.B.; Shawki, O.; Giacobbe, V.; Alibrandi, A.; Di Guardo, F.; Vitale, S.G. Reproductive outcomes of infertile women undergoing “see and treat” office hysteroscopy: A retrospective observational study. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2021, 30, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Haimovich, S.; Riemma, G.; Ludwin, A.; Zizolfi, B.; De Angelis, M.C.; Carugno, J. Innovations in hysteroscopic surgery: Expanding the meaning of “in-office". Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2021, 30, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G. The Biopsy Snake Grasper Sec. VITALE: A New Tool for Office Hysteroscopy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 1414–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, S.; Vitagliano, A.; Liu, X.; Liao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Vitale, S.G. Clinical Characteristics and Antifungal Susceptibility of Candida nivariensis from Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2020, 85, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).