Epigenetic Modulation of Opioid Receptors by Drugs of Abuse

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Physiology and Pharmacology of Opioid Receptors

3. Epigenetics and SUD

4. Drugs of Abuse Modify Epigenetic Regulation

4.1. DNA Methylation

4.2. Histone Modifications

4.3. ncRNAs

5. Epigenetic Modulation of Opioid Receptor Gene Expression by Drugs of Abuse

5.1. Epigenetic Modulation of the MOR Gene

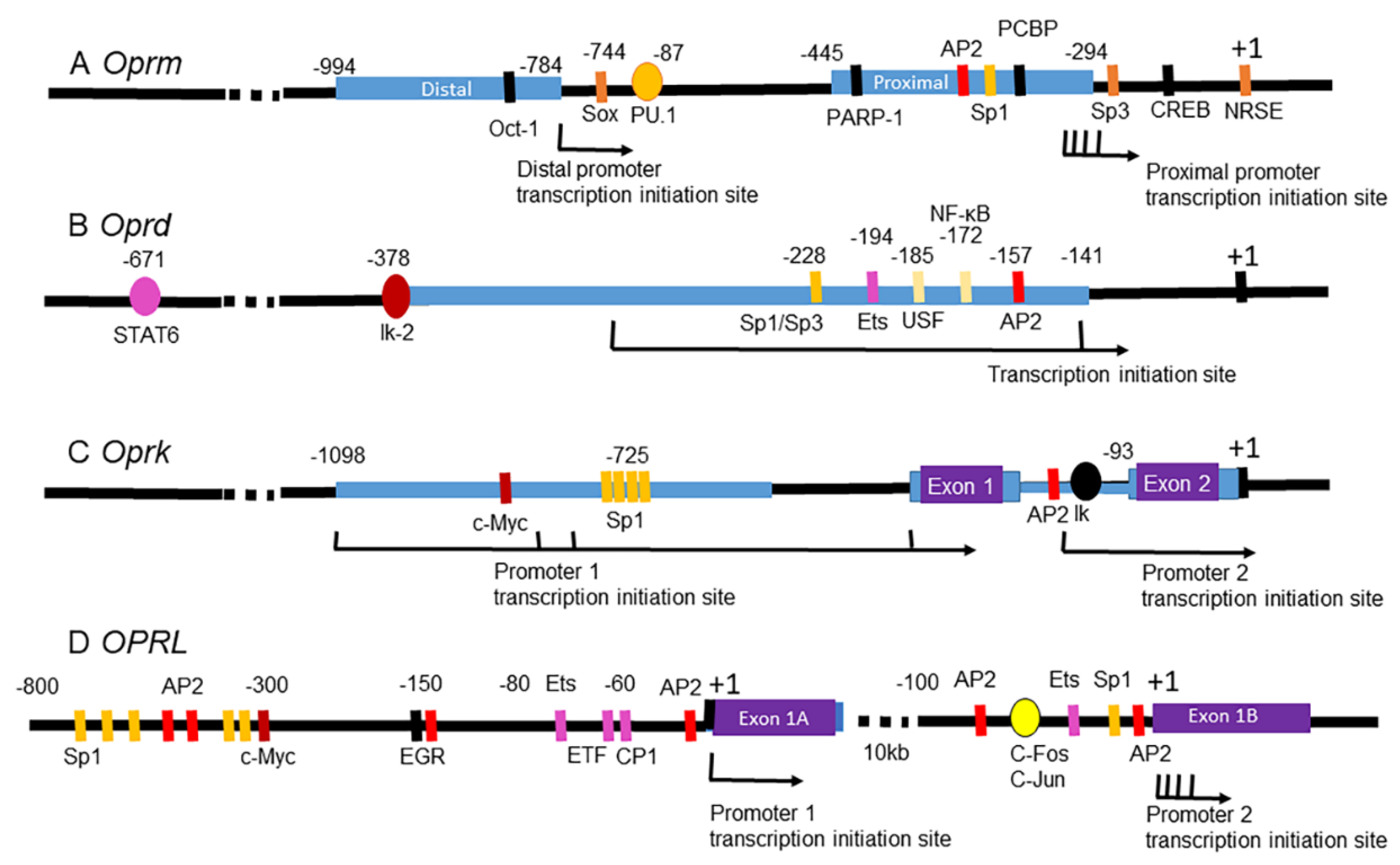

5.1.1. MOR Gene

5.1.2. MOR Gene Expression, DNA Methylation, and Drugs of Abuse

5.1.3. MOR Gene Expression, TFs, and Drugs of Abuse

5.1.4. MOR Gene Expression, ncRNAs, and Drugs of Abuse

5.2. Epigenetic Modulation of the DOR Gene

5.2.1. DOR Gene

5.2.2. OPRD1 SNPs and Drugs of Abuse

5.2.3. DOR Gene Expression and DNA Methylation

5.2.4. DOR Gene Expression, Chromatin Modulating Factors, and Drugs of Abuse

5.3. Epigenetic Modulations of the KOR Gene

5.3.1. KOR Gene

5.3.2. KOR Gene Expression, DNA Methylation, and Drugs of Abuse

5.3.3. KOR Gene Expression, Chromatin Modulating Factors, and Drugs of Abuse

5.3.4. KOR Gene Expression, TFs, and Drugs of Abuse

5.4. Epigenetic Modulation of the NOP Receptor Gene

5.4.1. NOP Receptor Gene

5.4.2. NOP Receptor Gene Expression and Drugs of Abuse

5.5. Summary and Perspective

6. Therapeutic Potentials of Drugs Epigenetically Targeting Opioid Receptor Gene Expression

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strang, J.; Volkow, N.D.; Degenhardt, L.; Hickman, M.; Johnson, K.; Koob, G.F.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Tyndall, M.; Walsh, S.L. Opioid use disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, F.; Lenoir, M.; Marie, N. The opioid receptors as targets for drug abuse medication. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 3964–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crist, R.C.; Reiner, B.C.; Berrettini, W.H. A review of opioid addiction genetics. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 27, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattore, L.; Fadda, P.; Antinori, S.; Fratta, W. Role of opioid receptors in the reinstatement of opioid-seeking behavior: An overview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1230, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Munoa, I.; Urizar, I.; Casis, L.; Irazusta, J.; Subiran, N. The epigenetic regulation of the opioid system: New individualized prompt prevention and treatment strategies. J. Cell Biochem. 2015, 116, 2419–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of opioid receptor genes: Present and future. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2011, 51, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Min, B.H.; Augustin, L.B.; Felsheim, R.F.; Fuchs, J.A.; Loh, H.H. Genomic structure analysis of promoter sequence of a mouse mu opioid receptor gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 9081–9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.C.; Lu, S.; Augustin, L.B.; Felsheim, R.F.; Chen, H.C.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Cloning and promoter mapping of mouse kappa opioid receptor gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 209, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, F.; Befort, K.; Gaveriaux-Ruff, C.; Matthes, H.; Nappey, V.; Lannes, B.; Micheletti, G.; Kieffer, B. The human delta-opioid receptor: Genomic organization, cDNA cloning, functional expression, and distribution in human brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994, 46, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Augustin, L.B.; Felsheim, R.F.; Min, B.H.; Fuchs, S.M.; Fuchs, J.A.; Loh, H.H. Genomic structure of the mouse delta opioid receptor gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 207, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toll, L.; Bruchas, M.R.; Calo, G.; Cox, B.M.; Zaveri, N.T. Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ Receptor Structure, Signaling, Ligands, Functions, and Interactions with Opioid Systems. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 419–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shenoy, S.S.; Lui, F. Biochemistry, Endogenous Opioids. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wtorek, K.; Janecka, A. Potential of Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ Peptide Analogs for Drug Development. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, e2000871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenian, P.; Vo, K.T.; Barr-Walker, J.; Lynch, K.L. Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: A comprehensive review. Neuropharmacology 2018, 134, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stein, C. Opioid Receptors. Annu. Rev. Med. 2016, 67, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Sarkar, S.; Chang, S.L. Opioid receptor expression in human brain and peripheral tissues using absolute quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2012, 124, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansour, A.; Fox, C.A.; Burke, S.; Akil, H.; Watson, S.J. Immunohistochemical localization of the cloned mu opioid receptor in the rat CNS. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 1995, 8, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tawfik, V.L.; Corder, G.; Low, S.A.; Francois, A.; Basbaum, A.I.; Scherrer, G. Functional Divergence of Delta and Mu Opioid Receptor Organization in CNS Pain Circuits. Neuron 2018, 98, 90–108.e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, A.K.; Smith, C.M.; Rahmatullah, M.; Nissapatorn, V.; Wilairatana, P.; Spetea, M.; Gueven, N.; Dietis, N. Opioid Analgesia and Opioid-Induced Adverse Effects: A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.D.; Henderson, G.; McKnight, A.T.; Paterson, S.J. 75 years of opioid research: The exciting but vain quest for the Holy Grail. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147 (Suppl. S1), S153–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pasternak, G.W.; Pan, Y.X. Mu opioids and their receptors: Evolution of a concept. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 1257–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathon, D.S.; Lesscher, H.M.; Gerrits, M.A.; Kamal, A.; Pintar, J.E.; Schuller, A.G.; Spruijt, B.M.; Burbach, J.P.; Smidt, M.P.; van Ree, J.M.; et al. Increased gabaergic input to ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons associated with decreased cocaine reinforcement in mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuroscience 2005, 130, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Grecksch, G.; Brodemann, R.; Kraus, J.; Peters, B.; Schroeder, H.; Thiemann, W.; Loh, H.H.; Hollt, V. Morphine self-administration in mu-opioid receptor-deficient mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000, 361, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.J.; McDonald, J.S.; Heyser, C.J.; Kieffer, B.L.; Matthes, H.W.; Koob, G.F.; Gold, L.H. mu-Opioid receptor knockout mice do not self-administer alcohol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 293, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sora, I.; Elmer, G.; Funada, M.; Pieper, J.; Li, X.F.; Hall, F.S.; Uhl, G.R. Mu opiate receptor gene dose effects on different morphine actions: Evidence for differential in vivo mu receptor reserve. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001, 25, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chefer, V.I.; Shippenberg, T.S. Augmentation of morphine-induced sensitization but reduction in morphine tolerance and reward in delta-opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gutierrez-Cuesta, J.; Burokas, A.; Mancino, S.; Kummer, S.; Martin-Garcia, E.; Maldonado, R. Effects of genetic deletion of endogenous opioid system components on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 2974–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berrendero, F.; Plaza-Zabala, A.; Galeote, L.; Flores, A.; Bura, S.A.; Kieffer, B.L.; Maldonado, R. Influence of delta-opioid receptors in the behavioral effects of nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 2332–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Rijn, R.M.; Whistler, J.L. The delta(1) opioid receptor is a heterodimer that opposes the actions of the delta(2) receptor on alcohol intake. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Rijn, R.M.; Brissett, D.I.; Whistler, J.L. Dual efficacy of delta opioid receptor-selective ligands for ethanol drinking and anxiety. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 335, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matuskey, D.; Dias, M.; Naganawa, M.; Pittman, B.; Henry, S.; Li, S.; Gao, H.; Ropchan, J.; Nabulsi, N.; Carson, R.E.; et al. Social status and demographic effects of the kappa opioid receptor: A PET imaging study with a novel agonist radiotracer in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 1714–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, M.L. The Rise and Fall of Kappa-Opioid Receptors in Drug Abuse Research. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2020, 258, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simonin, F.; Valverde, O.; Smadja, C.; Slowe, S.; Kitchen, I.; Dierich, A.; Le Meur, M.; Roques, B.P.; Maldonado, R.; Kieffer, B.L. Disruption of the kappa-opioid receptor gene in mice enhances sensitivity to chemical visceral pain, impairs pharmacological actions of the selective kappa-agonist U-50,488H and attenuates morphine withdrawal. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kovacs, K.M.; Szakall, I.; O’Brien, D.; Wang, R.; Vinod, K.Y.; Saito, M.; Simonin, F.; Kieffer, B.L.; Vadasz, C. Decreased oral self-administration of alcohol in kappa-opioid receptor knock-out mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005, 29, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van’t Veer, A.; Bechtholt, A.J.; Onvani, S.; Potter, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu-Chen, L.Y.; Schutz, G.; Chartoff, E.H.; Rudolph, U.; Cohen, B.M.; et al. Ablation of kappa-opioid receptors from brain dopamine neurons has anxiolytic-like effects and enhances cocaine-induced plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 1585–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nygard, S.K.; Hourguettes, N.J.; Sobczak, G.G.; Carlezon, W.A.; Bruchas, M.R. Stress-Induced Reinstatement of Nicotine Preference Requires Dynorphin/Kappa Opioid Activity in the Basolateral Amygdala. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 9937–9948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kiguchi, N.; Ding, H.; Ko, M.C. Central N/OFQ-NOP Receptor System in Pain Modulation. Adv. Pharmacol. 2016, 75, 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, D.G. The nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor: A target with broad therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, W.; Lambert, D.G.; Ko, M.C.; Koch, T. Functional plasticity of the N/OFQ-NOP receptor system determines analgesic properties of NOP receptor agonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 3777–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mogil, J.S.; Pasternak, G.W. The molecular and behavioral pharmacology of the orphanin FQ/nociceptin peptide and receptor family. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001, 53, 381–415. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, P.; Hamid, A.; Lutfy, K. The role of NOP receptors in psychomotor stimulation and locomotor sensitization induced by cocaine and amphetamine in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 707, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domi, A.; Lunerti, V.; Petrella, M.; Domi, E.; Borruto, A.M.; Ubaldi, M.; Weiss, F.; Ciccocioppo, R. Genetic deletion or pharmacological blockade of nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptors in the ventral tegmental area attenuates nicotine-motivated behaviour. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 2647–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunori, G.; Weger, M.; Schoch, J.; Targowska-Duda, K.; Barnes, M.; Borruto, A.M.; Rorick-Kehn, L.M.; Zaveri, N.T.; Pintar, J.E.; Ciccocioppo, R.; et al. NOP Receptor Antagonists Decrease Alcohol Drinking in the Dark in C57BL/6J Mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Luessen, D.J.; Kind, K.O.; Zhang, K.; Chen, R. Cocaine Self-administration Regulates Transcription of Opioid Peptide Precursors and Opioid Receptors in Rat Caudate Putamen and Prefrontal Cortex. Neuroscience 2020, 443, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Randesi, M.; Yuferov, V.; Zhao, C.; Kreek, M.J. Chronic Oxycodone Self-administration Altered Reward-related Genes in the Ventral and Dorsal Striatum of C57BL/6J Mice: An RNA-seq Analysis. Neuroscience 2018, 393, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, M.; Kaya, E.; Gozen, O.; Koylu, E.O.; Kanit, L.; Keser, A.; Balkan, B. Chronic nicotine-induced changes in gene expression of delta and kappa-opioid receptors and their endogenous ligands in the mesocorticolimbic system of the rat. Synapse 2017, 71, 3620996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, M.; Satoh, M. Molecular biology of the opioid receptors: Structures, functions and distributions. Neurosci. Res. 1995, 23, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Carey, M.; Workman, J.L. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 2007, 128, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kouzarides, T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 2007, 128, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Massart, R.; Barnea, R.; Dikshtein, Y.; Suderman, M.; Meir, O.; Hallett, M.; Kennedy, P.; Nestler, E.J.; Szyf, M.; Yadid, G. Role of DNA methylation in the nucleus accumbens in incubation of cocaine craving. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 8042–8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, A.; Choi, K.H.; Renthal, W.; Tsankova, N.M.; Theobald, D.E.; Truong, H.T.; Russo, S.J.; Laplant, Q.; Sasaki, T.S.; Whistler, K.N.; et al. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron 2005, 48, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastle, R.M.; Oliver, R.J.; Gardiner, A.S.; Pentkowski, N.S.; Bolognani, F.; Allan, A.M.; Chaudhury, T.; St Peter, M.; Galles, N.; Smith, C.; et al. In silico identification and in vivo validation of miR-495 as a novel regulator of motivation for cocaine that targets multiple addiction-related networks in the nucleus accumbens. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Byrnes, J.J.; Babb, J.A.; Scanlan, V.F.; Byrnes, E.M. Adolescent opioid exposure in female rats: Transgenerational effects on morphine analgesia and anxiety-like behavior in adult offspring. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 218, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Larsen, F.; Gundersen, G.; Lopez, R.; Prydz, H. CpG islands as gene markers in the human genome. Genomics 1992, 13, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; He, F.; Hu, S.; Yu, J. On the nature of human housekeeping genes. Trends Genet. 2008, 24, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carninci, P.; Sandelin, A.; Lenhard, B.; Katayama, S.; Shimokawa, K.; Ponjavic, J.; Semple, C.A.; Taylor, M.S.; Engstrom, P.G.; Frith, M.C.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of mammalian promoter architecture and evolution. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewa-Waclaw, J.; Bird, A.; von Schimmelmann, M.; Schaefer, A.; Yu, H.; Song, H.; Madabhushi, R.; Tsai, L.H. The Role of Epigenetic Mechanisms in the Regulation of Gene Expression in the Nervous System. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 11427–11434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kinde, B.; Gabel, H.W.; Gilbert, C.S.; Griffith, E.C.; Greenberg, M.E. Reading the unique DNA methylation landscape of the brain: Non-CpG methylation, hydroxymethylation, and MeCP2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6800–6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, L.; Gu, X.; Pan, Z.; Guo, X.; Liu, J.; Atianjoh, F.E.; Wu, S.; Mo, K.; Xu, B.; Liang, L.; et al. Contribution of DNMT1 to Neuropathic Pain Genesis Partially through Epigenetically Repressing Kcna2 in Primary Afferent Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 6595–6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bian, K.; Lenz, S.A.P.; Tang, Q.; Chen, F.; Qi, R.; Jost, M.; Drennan, C.L.; Essigmann, J.M.; Wetmore, S.D.; Li, D. DNA repair enzymes ALKBH2, ALKBH3, and AlkB oxidize 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5522–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, D.Q.; Ali, I.; Tang, J.; Yang, W.C. New Insights into 5hmC DNA Modification: Generation, Distribution and Function. Front Genet. 2017, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kriaucionis, S.; Heintz, N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science 2009, 324, 929–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stoyanova, E.; Riad, M.; Rao, A.; Heintz, N. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine-mediated active demethylation is required for mammalian neuronal differentiation and function. Elife 2021, 10, e66973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrow, T.M.; Byun, H.M.; Li, X.; Smart, C.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Guo, L. The effect of morphine upon DNA methylation in ten regions of the rat brain. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wei, W.; Ratnu, V.S.; Bredy, T.W. On the potential role of active DNA demethylation in establishing epigenetic states associated with neural plasticity and memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2013, 105, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anier, K.; Urb, M.; Kipper, K.; Herodes, K.; Timmusk, T.; Zharkovsky, A.; Kalda, A. Cocaine-induced epigenetic DNA modification in mouse addiction-specific and non-specific tissues. Neuropharmacology 2018, 139, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Kennani, S.; Crespo, M.; Govin, J.; Pflieger, D. Proteomic Analysis of Histone Variants and Their PTMs: Strategies and Pitfalls. Proteomes 2018, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrelly, L.A.; Thompson, R.E.; Zhao, S.; Lepack, A.E.; Lyu, Y.; Bhanu, N.V.; Zhang, B.; Loh, Y.E.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Vadodaria, K.C.; et al. Histone serotonylation is a permissive modification that enhances TFIID binding to H3K4me3. Nature 2019, 567, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalda, A.; Zharkovsky, A. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Psychostimulant-Induced Addiction. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2015, 120, 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack, J.P.; Pandey, S.C. Histone modifications, DNA methylation, and the epigenetic code of alcohol use disorder. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2021, 156, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rogge, G.A.; Wood, M.A. The role of histone acetylation in cocaine-induced neural plasticity and behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egervari, G.; Landry, J.; Callens, J.; Fullard, J.F.; Roussos, P.; Keller, E.; Hurd, Y.L. Striatal H3K27 Acetylation Linked to Glutamatergic Gene Dysregulation in Human Heroin Abusers Holds Promise as Therapeutic Target. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 81, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calo, E.; Wysocka, J. Modification of enhancer chromatin: What, how, and why? Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pradeepa, M.M. Causal role of histone acetylations in enhancer function. Transcription 2017, 8, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.S.; Xu, W.J.; Zhu, H.Q.; Gao, L.; Lai, M.J.; Zhang, F.Q.; Zhou, W.H.; Liu, H.F. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate on heroin seeking behavior in the nucleus accumbens in rats. Brain Res. 2016, 1652, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, C.J.; Godino, A.; Salery, M.; Nestler, E.J. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Opioid Addiction. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, F.S.; Fischl, H.; Murray, S.C.; Mellor, J. Is H3K4me3 instructive for transcription activation? Bioessays 2017, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitchcock, L.N.; Lattal, K.M. Histone-mediated epigenetics in addiction. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2014, 128, 51–87. [Google Scholar]

- Maze, I.; Covington, H.E., 3rd; Dietz, D.M.; LaPlant, Q.; Renthal, W.; Russo, S.J.; Mechanic, M.; Mouzon, E.; Neve, R.L.; Haggarty, S.J.; et al. Essential role of the histone methyltransferase G9a in cocaine-induced plasticity. Science 2010, 327, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damez-Werno, D.M.; Sun, H.; Scobie, K.N.; Shao, N.; Rabkin, J.; Dias, C.; Calipari, E.S.; Maze, I.; Pena, C.J.; Walker, D.M.; et al. Histone arginine methylation in cocaine action in the nucleus accumbens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9623–9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guccione, E.; Bassi, C.; Casadio, F.; Martinato, F.; Cesaroni, M.; Schuchlautz, H.; Luscher, B.; Amati, B. Methylation of histone H3R2 by PRMT6 and H3K4 by an MLL complex are mutually exclusive. Nature 2007, 449, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmizis, A.; Santos-Rosa, H.; Penkett, C.J.; Singer, M.A.; Vermeulen, M.; Mann, M.; Bahler, J.; Green, R.D.; Kouzarides, T. Arginine methylation at histone H3R2 controls deposition of H3K4 trimethylation. Nature 2007, 449, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feng, J.; Wilkinson, M.; Liu, X.; Purushothaman, I.; Ferguson, D.; Vialou, V.; Maze, I.; Shao, N.; Kennedy, P.; Koo, J.; et al. Chronic cocaine-regulated epigenomic changes in mouse nucleus accumbens. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Clark, M.B.; Amaral, P.P.; Schlesinger, F.J.; Dinger, M.E.; Taft, R.J.; Rinn, J.L.; Ponting, C.P.; Stadler, P.F.; Morris, K.V.; Morillon, A.; et al. The reality of pervasive transcription. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1000625; discussion e1001102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palazzo, A.F.; Koonin, E.V. Functional Long Non-coding RNAs Evolve from Junk Transcripts. Cell 2020, 183, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaefer, A.; Im, H.I.; Veno, M.T.; Fowler, C.D.; Min, A.; Intrator, A.; Kjems, J.; Kenny, P.J.; O’Carroll, D.; Greengard, P. Argonaute 2 in dopamine 2 receptor-expressing neurons regulates cocaine addiction. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Hwang, C.K.; Zheng, H.; Wagley, Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Kim, D.K.; Law, P.Y.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. MicroRNA 339 down-regulates mu-opioid receptor at the post-transcriptional level in response to opioid treatment. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sim, M.S.; Soga, T.; Pandy, V.; Wu, Y.S.; Parhar, I.S.; Mohamed, Z. MicroRNA expression signature of methamphetamine use and addiction in the rat nucleus accumbens. Metab. Brain Dis. 2017, 32, 1767–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Duan, M.; Zhu, X.; Huang, W.; Chao, J.; Zhou, R.; et al. Silencing microRNA-143 protects the integrity of the blood-brain barrier: Implications for methamphetamine abuse. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.J.; Qiu, Y.; Hua, Z. The Emerging Perspective of Morphine Tolerance: MicroRNAs. Pain Res. Manag. 2019, 2019, 9432965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bali, P.; Kenny, P.J. Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 21, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barbierato, M.; Zusso, M.; Skaper, S.D.; Giusti, P. MicroRNAs: Emerging role in the endogenous mu opioid system. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowen, A.M.; Odegaard, K.E.; Hernandez, J.; Chand, S.; Koul, S.; Pendyala, G.; Yelamanchili, S.V. Role of microRNAs in the pathophysiology of addiction. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2021, 12, e1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelhaugh, S.K.; Lipovich, L.; Blythe, J.; Jia, H.; Kapatos, G.; Bannon, M.J. Mining Affymetrix microarray data for long non-coding RNAs: Altered expression in the nucleus accumbens of heroin abusers. J. Neurochem. 2011, 116, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Albertson, D.N.; Schmidt, C.J.; Kapatos, G.; Bannon, M.J. Distinctive profiles of gene expression in the human nucleus accumbens associated with cocaine and heroin abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, L.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Chen, S.; Li, T.; Dang, Y.; Chen, T. Methamphetamine induces alterations in the long non-coding RNAs expression profile in the nucleus accumbens of the mouse. BMC Neurosci. 2015, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, E.; Gao, H. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 attends to morphine-mediated autophagy of HT22 cells through modulating ERK pathway. Pharm. Biol. 2019, 57, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Namvar, A.; Kahaei, M.S.; Fallah, H.; Nicknafs, F.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Taheri, M. ANRIL Variants Are Associated with Risk of Neuropsychiatric Conditions. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 70, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levran, O.; Randesi, M.; Rotrosen, J.; Ott, J.; Adelson, M.; Kreek, M.J. A 3′ UTR SNP rs885863, a cis-eQTL for the circadian gene VIPR2 and lincRNA 689, is associated with opioid addiction. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rybak-Wolf, A.; Stottmeister, C.; Glazar, P.; Jens, M.; Pino, N.; Giusti, S.; Hanan, M.; Behm, M.; Bartok, O.; Ashwal-Fluss, R.; et al. Circular RNAs in the Mammalian Brain Are Highly Abundant, Conserved, and Dynamically Expressed. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 870–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bu, Q.; Long, H.; Shao, X.; Gu, H.; Kong, J.; Luo, L.; Liu, B.; Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Tian, J.; et al. Cocaine induces differential circular RNA expression in striatum. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cadet, J.L.; Jayanthi, S. Epigenetics of addiction. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 147, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elde, R.; Arvidsson, U.; Riedl, M.; Vulchanova, L.; Lee, J.H.; Dado, R.; Nakano, A.; Chakrabarti, S.; Zhang, X.; Loh, H.H.; et al. Distribution of neuropeptide receptors. New views of peptidergic neurotransmission made possible by antibodies to opioid receptors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1995, 757, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Regulation of opioid receptor expression. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2002, 2, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.Y.; Choi, H.S.; Hwang, C.K.; Kim, C.S.; Law, P.Y.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Differential use of an in-frame translation initiation codon regulates human mu opioid receptor (OPRM1). Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 2933–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabalina, S.A.; Zaykin, D.V.; Gris, P.; Ogurtsov, A.Y.; Gauthier, J.; Shibata, K.; Tchivileva, I.E.; Belfer, I.; Mishra, B.; Kiselycznyk, C.; et al. Expansion of the human mu-opioid receptor gene architecture: Novel functional variants. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.Y.; Hwang, C.K.; Kim, C.S.; Choi, H.S.; Law, P.Y.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Translational repression of mouse mu opioid receptor expression via leaky scanning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 1501–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.L.; Minnerath, S.R.; Loh, H.H. Dual promoters of mouse mu-opioid receptor gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 234, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, D.L.; Keith, D.E., Jr.; Anton, B.; Tian, J.; Magendzo, K.; Newman, D.; Tran, T.H.; Lee, D.S.; Wen, C.; Xia, Y.R.; et al. Characterization of the murine mu opioid receptor gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 15877–15883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, Z.; Xu, J.; Xu, M.; Pasternak, G.W.; Pan, Y.X. Morphine regulates expression of mu-opioid receptor MOR-1A, an intron-retention carboxyl terminal splice variant of the mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) gene via miR-103/miR-107. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 85, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, J.; Pan, Y.X. A Truncated Six Transmembrane Splice Variant MOR-1G Enhances Expression of the Full-Length Seven Transmembrane mu-Opioid Receptor through Heterodimerization. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020, 98, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xu, M.; Brown, T.; Rossi, G.C.; Hurd, Y.L.; Inturrisi, C.E.; Pasternak, G.W.; Pan, Y.X. Stabilization of the mu-opioid receptor by truncated single transmembrane splice variants through a chaperone-like action. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 21211–21227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosin, A.; Kitchen, I.; Georgieva, J. Effects of single and dual administration of cocaine and ethanol on opioid and ORL1 receptor expression in rat CNS: An autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 2003, 978, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dash, S.; Balasubramaniam, M.; Martinez-Rivera, F.J.; Godino, A.; Peck, E.G.; Patnaik, S.; Suar, M.; Calipari, E.S.; Nestler, E.J.; Villalta, F.; et al. Cocaine-regulated microRNA miR-124 controls poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 expression in neuronal cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaryan, A.V.; Coughlin, L.J.; Buzas, B.; Clock, B.J.; Cox, B.M. Effect of chronic cocaine treatment on mu- and delta-opioid receptor mRNA levels in dopaminergically innervated brain regions. J. Neurochem. 1996, 66, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuferov, V.; Zhou, Y.; Spangler, R.; Maggos, C.E.; Ho, A.; Kreek, M.J. Acute “binge” cocaine increases mu-opioid receptor mRNA levels in areas of the rat mesolimbic mesocortical dopamine system. Brain Res. Bull. 1999, 48, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, A.; Lindholm, S.; Franck, J.; Georgieva, J. Downregulation of kappa opioid receptor mRNA levels by chronic ethanol and repetitive cocaine in rat ventral tegmentum and nucleus accumbens. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 275, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, R.; Zhou, Y.; Maggos, C.E.; Schlussman, S.D.; Ho, A.; Kreek, M.J. Prodynorphin, proenkephalin and kappa opioid receptor mRNA responses to acute “binge” cocaine. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1997, 44, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, E.; Chen, J.; Zagouras, P.; Magna, H.; Holland, J.; Schaeffer, E.; Nestler, E.J. Induction of nuclear factor-kappaB in nucleus accumbens by chronic cocaine administration. J. Neurochem. 2001, 79, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, A.J.; Vialou, V.; Mazei-Robison, M.; Feng, J.; Kourrich, S.; Collins, M.; Wee, S.; Koob, G.; Turecki, G.; Neve, R.; et al. Behavioral and structural responses to chronic cocaine require a feedforward loop involving DeltaFosB and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the nucleus accumbens shell. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 4295–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russo, S.J.; Wilkinson, M.B.; Mazei-Robison, M.S.; Dietz, D.M.; Maze, I.; Krishnan, V.; Renthal, W.; Graham, A.; Birnbaum, S.G.; Green, T.A.; et al. Nuclear factor kappa B signaling regulates neuronal morphology and cocaine reward. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 3529–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Valenza, M.; Picetti, R.; Yuferov, V.; Butelman, E.R.; Kreek, M.J. Strain and cocaine-induced differential opioid gene expression may predispose Lewis but not Fischer rats to escalate cocaine self-administration. Neuropharmacology 2016, 105, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailey, A.; Yuferov, V.; Bendor, J.; Schlussman, S.D.; Zhou, Y.; Ho, A.; Kreek, M.J. Immediate withdrawal from chronic “binge” cocaine administration increases mu-opioid receptor mRNA levels in rat frontal cortex. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005, 137, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputi, F.F.; Di Benedetto, M.; Carretta, D.; Bastias del Carmen Candia, S.; D’Addario, C.; Cavina, C.; Candeletti, S.; Romualdi, P. Dynorphin/KOP and nociceptin/NOP gene expression and epigenetic changes by cocaine in rat striatum and nucleus accumbens. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 49, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, F.; Zhou, Y.; Goddard, B.; Cummins, E.; Kreek, M.J. Effects of high-dose methadone maintenance on cocaine place conditioning, cocaine self-administration, and mu-opioid receptor mRNA expression in the rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 1462–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, S.; Cheeran, M.C.; Sheng, W.S.; Ni, H.T.; Lokensgard, J.R.; Peterson, P.K. Cocaine alters proliferation, migration, and differentiation of human fetal brain-derived neural precursor cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 318, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, F.F.; Palmisano, M.; Carboni, L.; Candeletti, S.; Romualdi, P. Opioid gene expression changes and post-translational histone modifications at promoter regions in the rat nucleus accumbens after acute and repeated 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) exposure. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 114, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobskind, J.S.; Rosinger, Z.J.; Brooks, M.L.; Zuloaga, D.G. Stress-induced neural activation is altered during early withdrawal from chronic methamphetamine. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 366, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.T.; Ma, T.; Ho, I.K. Methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice: Alterations in mu-opioid receptor. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006, 13, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramezany Yasuj, S.; Nourhashemi, M.; Keshavarzi, S.; Motaghinejad, M.; Motevalian, M. Possible Role of Cyclic AMP Response Element Binding/Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Signaling Pathway in Mediating the Pharmacological Effects of Duloxetine against Methamphetamine Use-Induced Cognitive Impairment and Withdrawal-Induced Anxiety and Depression in Rats. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2019, 8, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, P.; Zanos, P.; Garcia-Carmona, J.A.; Hourani, S.; Kitchen, I.; Laorden, M.L.; Bailey, A. Methamphetamine abstinence induces changes in mu-opioid receptor, oxytocin and CRF systems: Association with an anxiogenic phenotype. Neuropharmacology 2016, 105, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niinep, K.; Anier, K.; Etelainen, T.; Piepponen, P.; Kalda, A. Repeated Ethanol Exposure Alters DNA Methylation Status and Dynorphin/Kappa-Opioid Receptor Expression in Nucleus Accumbens of Alcohol-Preferring AA Rats. Front Genet. 2021, 12, 750142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darlington, T.M.; McCarthy, R.D.; Cox, R.J.; Miyamoto-Ditmon, J.; Gallego, X.; Ehringer, M.A. Voluntary wheel running reduces voluntary consumption of ethanol in mice: Identification of candidate genes through striatal gene expression profiling. Genes Brain Behav. 2016, 15, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Waele, J.P.; Gianoulakis, C. Characterization of the mu and delta opioid receptors in the brain of the C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice, selected for their differences in voluntary ethanol consumption. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1997, 21, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, C.M.; Wei, G.; Walker, B.M. Maladaptive behavioral regulation in alcohol dependence: Role of kappa-opioid receptors in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Neuropharmacology 2018, 140, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, A.; Bazov, I.; Sheedy, D.; Garrick, T.; Harper, C.; Bakalkin, G. Expression of pronociceptin and its receptor is downregulated in the brain of human alcoholics. Brain Res. 2009, 1305, S80–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molina-Martinez, L.M.; Juarez, J. Differential expression of mu-opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens, amygdala and VTA depends on liking for alcohol, chronic alcohol intake and estradiol treatment. Behav. Brain Res. 2020, 378, 112255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, K.; Staehle, M.M.; Vadigepalli, R.; Gonye, G.E.; Ogunnaike, B.A.; Hoek, J.B.; Schwaber, J.S. Coordinated dynamic gene expression changes in the central nucleus of the amygdala during alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37 (Suppl. S1), E88–E100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marinelli, P.W.; Funk, D.; Juzytsch, W.; Li, Z.; Le, A.D. Effects of opioid receptor blockade on the renewal of alcohol seeking induced by context: Relationship to c-fos mRNA expression. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 26, 2815–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputi, F.F.; Lattanzio, F.; Carretta, D.; Mercatelli, D.; Candeletti, S.; Romualdi, P. Morphine and fentanyl differently affect MOP and NOP gene expression in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2013, 51, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.W.; Lee, Y.M. Transcriptional regulation of mu opioid receptor gene by cAMP pathway. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 64, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morinville, A.; Cahill, C.M.; Esdaile, M.J.; Aibak, H.; Collier, B.; Kieffer, B.L.; Beaudet, A. Regulation of delta-opioid receptor trafficking via mu-opioid receptor stimulation: Evidence from mu-opioid receptor knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 4888–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levran, O.; Londono, D.; O’Hara, K.; Nielsen, D.A.; Peles, E.; Rotrosen, J.; Casadonte, P.; Linzy, S.; Randesi, M.; Ott, J.; et al. Genetic susceptibility to heroin addiction: A candidate gene association study. Genes Brain Behav. 2008, 7, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Theberge, F.R.; Pickens, C.L.; Goldart, E.; Fanous, S.; Hope, B.T.; Liu, Q.R.; Shaham, Y. Association of time-dependent changes in mu opioid receptor mRNA, but not BDNF, TrkB, or MeCP2 mRNA and protein expression in the rat nucleus accumbens with incubation of heroin craving. Psychopharmacology 2012, 224, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, L.X.; Dong, Y.P.; Zhu, Q.M.; Zhang, B.; Ai, B.L.; Yan, T.; Zhang, G.H.; Sun, L. Effects of dezocine on morphine tolerance and opioid receptor expression in a rat model of bone cancer pain. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Law, P.Y.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Long-term morphine treatment decreases the association of mu-opioid receptor (MOR1) mRNA with polysomes through miRNA23b. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 75, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Douglas, S.D.; Commons, K.G.; Pleasure, D.E.; Lai, J.; Ho, C.; Bannerman, P.; Williams, M.; Ho, W. A non-peptide substance P antagonist (CP-96,345) inhibits morphine-induced NF-kappa B promoter activation in human NT2-N neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 75, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariou, V.; Bolanos, C.A.; Selley, D.E.; Theobald, D.; Cassidy, M.P.; Kelz, M.B.; Shaw-Lutchman, T.; Berton, O.; Sim-Selley, L.J.; Dileone, R.J.; et al. An essential role for DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens in morphine action. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moron, J.A.; Abul-Husn, N.S.; Rozenfeld, R.; Dolios, G.; Wang, R.; Devi, L.A. Morphine administration alters the profile of hippocampal postsynaptic density-associated proteins: A proteomics study focusing on endocytic proteins. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2007, 6, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, D.Y.; Li, X.; Clark, J.D. Epigenetic regulation of opioid-induced hyperalgesia, dependence, and tolerance in mice. J. Pain 2013, 14, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deng, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, M.; Liang, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Jiang, S.; Weng, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zou, W. LncRNA MRAK159688 facilitates morphine tolerance by promoting REST-mediated inhibition of mu opioid receptor in rats. Neuropharmacology 2022, 206, 108938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Oxycodone regulates incision-induced activation of neurotrophic factors and receptors in an acute post-surgery pain rat model. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ito, E.; Xie, G.; Maruyama, K.; Palmer, P.P. A core-promoter region functions bi-directionally for human opioid-receptor-like gene ORL1 and its 5’-adjacent gene GAIP. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 304, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, C.K.; Song, K.Y.; Kim, C.S.; Choi, H.S.; Guo, X.H.; Law, P.Y.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Evidence of endogenous mu opioid receptor regulation by epigenetic control of the promoters. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 4720–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hwang, C.K.; Kim, C.S.; Choi, H.S.; McKercher, S.R.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional regulation of mouse mu opioid receptor gene by PU.1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 19764–19774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandoval-Sierra, J.V.; Salgado Garcia, F.I.; Brooks, J.H.; Derefinko, K.J.; Mozhui, K. Effect of short-term prescription opioids on DNA methylation of the OPRM1 promoter. Clin. Epigenet. 2020, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, D.A.; Yuferov, V.; Hamon, S.; Jackson, C.; Ho, A.; Ott, J.; Kreek, M.J. Increased OPRM1 DNA methylation in lymphocytes of methadone-maintained former heroin addicts. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, B.G.; Doehring, A.; Roskam, B.; Kettner, M.; Hackmann, N.; Ferreiros, N.; Schmidt, P.H.; Lotsch, J. Genetic-epigenetic interaction modulates mu-opioid receptor regulation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 4751–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doehring, A.; Oertel, B.G.; Sittl, R.; Lotsch, J. Chronic opioid use is associated with increased DNA methylation correlating with increased clinical pain. Pain 2013, 154, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorbov, V.M.; Todorov, A.A.; Lynskey, M.T.; Cicero, T.J. Elevated levels of DNA methylation at the OPRM1 promoter in blood and sperm from male opioid addicts. J. Opioid Manag. 2011, 7, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachman, E.M.; Hayes, M.J.; Lester, B.M.; Terrin, N.; Brown, M.S.; Nielsen, D.A.; Davis, J.M. Epigenetic variation in the mu-opioid receptor gene in infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. J. Pediatr. 2014, 165, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, N.; Yu, L.; Gao, Y.; Ma, L.; Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, D.S.; Xie, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. MeCP2 Epigenetic Silencing of Oprm1 Gene in Primary Sensory Neurons Under Neuropathic Pain Conditions. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 743207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Tao, W.; Hou, Y.Y.; Wang, W.; Kenny, P.J.; Pan, Z.Z. MeCP2 repression of G9a in regulation of pain and morphine reward. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 9076–9087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, Y.; Wang, Z.J. Let-7 microRNAs and Opioid Tolerance. Front. Genet. 2012, 3, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turek-Plewa, J.; Jagodzinski, P.P. The role of mammalian DNA methyltransferases in the regulation of gene expression. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2005, 10, 631–647. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, X.; Xiong, M.; Cai, W.; Atianjoh, F.E.; Jobe, E.E.; Zhao, X.; Tu, W.F.; Tao, Y.X. MBD1 Contributes to the Genesis of Acute Pain and Neuropathic Pain by Epigenetic Silencing of Oprm1 and Kcna2 Genes in Primary Sensory Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 9883–9899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeal, W.; Benfield, P. Transdermal fentanyl. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in pain control. Drugs 1997, 53, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolizzi, J.; Boger, R.H.; Budd, K.; Dahan, A.; Erdine, S.; Hans, G.; Kress, H.G.; Langford, R.; Likar, R.; Raffa, R.B.; et al. Opioids and the management of chronic severe pain in the elderly: Consensus statement of an International Expert Panel with focus on the six clinically most often used World Health Organization Step III opioids (buprenorphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone). Pain Pract. 2008, 8, 287–313. [Google Scholar]

- Duttaroy, A.; Yoburn, B.C. The effect of intrinsic efficacy on opioid tolerance. Anesthesiology 1995, 82, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, S.; Ferrone, M. Fentanyl HCl patient-controlled iontophoretic transdermal system for the management of acute postoperative pain. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006, 40, 2178–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.L.; Liu, H.C.; Loh, H.H. Role of an AP-2-like element in transcriptional regulation of mouse mu-opioid receptor gene. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2003, 112, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Carr, L.G. Binding of Sp1/Sp3 to the proximal promoter of the hMOR gene is enhanced by DAMGO. Gene 2001, 274, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.J.; Smirnov, D.; Yuhi, T.; Raghavan, S.; Olsson, J.E.; Muscat, G.E.; Koopman, P.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional modulation of mouse mu-opioid receptor distal promoter activity by Sox18. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hwang, C.K.; Wu, X.; Wang, G.; Kim, C.S.; Loh, H.H. Mouse mu opioid receptor distal promoter transcriptional regulation by SOX proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 3742–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nennig, S.E.; Schank, J.R. The Role of NFkB in Drug Addiction: Beyond Inflammation. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017, 52, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, C.D.; Nestler, E.J. Key transcription factors mediating cocaine-induced plasticity in the nucleus accumbens. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, J.; Borner, C.; Giannini, E.; Hollt, V. The role of nuclear factor kappaB in tumor necrosis factor-regulated transcription of the human mu-opioid receptor gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 64, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, B.T.; Nye, H.E.; Kelz, M.B.; Self, D.W.; Iadarola, M.J.; Nakabeppu, Y.; Duman, R.S.; Nestler, E.J. Induction of a long-lasting AP-1 complex composed of altered Fos-like proteins in brain by chronic cocaine and other chronic treatments. Neuron 1994, 13, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratalla, R.; Elibol, B.; Vallejo, M.; Graybiel, A.M. Network-level changes in expression of inducible Fos-Jun proteins in the striatum during chronic cocaine treatment and withdrawal. Neuron 1996, 17, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilecki, W.; Wawrzczak-Bargiela, A.; Przewlocki, R. Activation of AP-1 and CRE-dependent gene expression via mu-opioid receptor. J. Neurochem. 2004, 90, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borner, C.; Hollt, V.; Kraus, J. Involvement of activator protein-1 in transcriptional regulation of the human mu-opioid receptor gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 61, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perrotti, L.I.; Weaver, R.R.; Robison, B.; Renthal, W.; Maze, I.; Yazdani, S.; Elmore, R.G.; Knapp, D.J.; Selley, D.E.; Martin, B.R.; et al. Distinct patterns of DeltaFosB induction in brain by drugs of abuse. Synapse 2008, 62, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McDaid, J.; Graham, M.P.; Napier, T.C. Methamphetamine-induced sensitization differentially alters pCREB and DeltaFosB throughout the limbic circuit of the mammalian brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nye, H.E.; Nestler, E.J. Induction of chronic Fos-related antigens in rat brain by chronic morphine administration. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996, 49, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pich, E.M.; Pagliusi, S.R.; Tessari, M.; Talabot-Ayer, D.; Hooft van Huijsduijnen, R.; Chiamulera, C. Common neural substrates for the addictive properties of nicotine and cocaine. Science 1997, 275, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestler, E.J.; Barrot, M.; Self, D.W. DeltaFosB: A sustained molecular switch for addiction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11042–11046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levine, A.A.; Guan, Z.; Barco, A.; Xu, S.; Kandel, E.R.; Schwartz, J.H. CREB-binding protein controls response to cocaine by acetylating histones at the fosB promoter in the mouse striatum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 19186–19191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Lv, Z.; Hu, Z.; Sheng, J.; Hui, B.; Sun, J.; Ma, L. Chronic cocaine-induced H3 acetylation and transcriptional activation of CaMKIIalpha in the nucleus accumbens is critical for motivation for drug reinforcement. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gajewski, P.A.; Eagle, A.L.; Williams, E.S.; Manning, C.E.; Lynch, H.; McCornack, C.; Maze, I.; Heller, E.A.; Robison, A.J. Epigenetic Regulation of Hippocampal Fosb Expression Controls Behavioral Responses to Cocaine. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8305–8314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Pandey, K.K.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Law, P.Y.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Poly(C) binding protein family is a transcription factor in mu-opioid receptor gene expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borner, C.; Woltje, M.; Hollt, V.; Kraus, J. STAT6 transcription factor binding sites with mismatches within the canonical 5′-TTC...GAA-3’ motif involved in regulation of delta- and mu-opioid receptors. J. Neurochem. 2004, 91, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borner, C.; Hollt, V.; Kraus, J. Cannabinoid receptor type 2 agonists induce transcription of the mu-opioid receptor gene in Jurkat T cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borner, C.; Kraus, J.; Bedini, A.; Schraven, B.; Hollt, V. T-cell receptor/CD28-mediated activation of human T lymphocytes induces expression of functional mu-opioid receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendel, B.; Hoehe, M.R. The human mu opioid receptor gene: 5′ regulatory and intronic sequences. J. Mol. Med. 1998, 76, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; Guo, L.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Jiang, W.; Liu, X.; McNutt, M.A.; Li, G. Mechanisms involved in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway mediated up-regulation of the mu opioid receptor in lymphocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T.; Kaneda, T.; Muto, A.; Yoshida, T. Positive transcriptional regulation of the human micro opioid receptor gene by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and increase of its DNA binding affinity based on polymorphism of G-172 -> T. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 20175–20183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.E.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, T.C. PARP1 activation/expression modulates regional-specific neuronal and glial responses to seizure in a hemodynamic-independent manner. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brochier, C.; Jones, J.I.; Willis, D.E.; Langley, B. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 is a novel target to promote axonal regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15220–15225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoica, B.A.; Loane, D.J.; Zhao, Z.; Kabadi, S.V.; Hanscom, M.; Byrnes, K.R.; Faden, A.I. PARP-1 inhibition attenuates neuronal loss, microglia activation and neurological deficits after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 758–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Hwang, C.K.; Kim, C.S.; Song, K.Y.; Law, P.Y.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Transcriptional regulation of mouse mu opioid receptor gene in neuronal cells by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2008, 12, 2319–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andria, M.L.; Simon, E.J. Identification of a neurorestrictive suppressor element (NRSE) in the human mu-opioid receptor gene. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001, 91, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Carr, L.G. Identification of an octamer-1 transcription factor binding site in the promoter of the mouse mu-opioid receptor gene. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Hwang, C.K.; Kim, C.S.; Song, K.Y.; Law, P.Y.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional regulation of mouse mu opioid receptor gene: Sp3 isoforms (M1, M2) function as repressors in neuronal cells to regulate the mu opioid receptor gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Han, W.; Kasai, S.; Hata, H.; Takahashi, T.; Takamatsu, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Uhl, G.R.; Sora, I.; Ikeda, K. Intracisternal A-particle element in the 3’ noncoding region of the mu-opioid receptor gene in CXBK mice: A new genetic mechanism underlying differences in opioid sensitivity. Pharm. Genom. 2006, 16, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, S.; Han, W.; Kasai, S.; Hata, H.; Sora, I.; Ikeda, K. Characterization of the 3’ untranslated region of the human mu-opioid receptor (MOR-1) mRNA. Gene 2005, 364, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, C.K.; Wagley, Y.; Law, P.Y.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. MicroRNAs in opioid pharmacology. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012, 7, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, Y.; Yang, C.; Kirkmire, C.M.; Wang, Z.J. Regulation of opioid tolerance by let-7 family microRNA targeting the mu opioid receptor. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 10251–10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehta, S.L.; Kim, T.; Vemuganti, R. Long Noncoding RNA FosDT Promotes Ischemic Brain Injury by Interacting with REST-Associated Chromatin-Modifying Proteins. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 16443–16449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dharap, A.; Pokrzywa, C.; Vemuganti, R. Increased binding of stroke-induced long non-coding RNAs to the transcriptional corepressors Sin3A and coREST. ASN Neuro 2013, 5, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, C.; Pan, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zou, W. Identification of lncRNA expression profiles and ceRNA analysis in the spinal cord of morphine-tolerant rats. Mol. Brain 2018, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irie, T.; Shum, R.; Deni, I.; Hunkele, A.; Le Rouzic, V.; Xu, J.; Wilson, R.; Fischer, G.W.; Pasternak, G.W.; Pan, Y.X. Identification of Abundant and Evolutionarily Conserved Opioid Receptor Circular RNAs in the Nervous System Modulated by Morphine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 96, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Faskowitz, A.J.; Rossi, G.C.; Xu, M.; Lu, Z.; Pan, Y.X.; Pasternak, G.W. Stabilization of morphine tolerance with long-term dosing: Association with selective upregulation of mu-opioid receptor splice variant mRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Efficient backsplicing produces translatable circular mRNAs. RNA 2015, 21, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, J.M.; Margolis, E.B.; Coker, A.R.; Allen, D.C.; Fields, H.L. Intra-VTA deltorphin, but not DPDPE, induces place preference in ethanol-drinking rats: Distinct DOR-1 and DOR-2 mechanisms control ethanol consumption and reward. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2014, 38, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Merrer, J.; Rezai, X.; Scherrer, G.; Becker, J.A.; Kieffer, B.L. Impaired hippocampus-dependent and facilitated striatum-dependent behaviors in mice lacking the delta opioid receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Randall-Thompson, J.F.; Pescatore, K.A.; Unterwald, E.M. A role for delta opioid receptors in the central nucleus of the amygdala in anxiety-like behaviors. Psychopharmacology 2010, 212, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uhl, G.R.; Childers, S.; Pasternak, G. An opiate-receptor gene family reunion. Trends Neurosci. 1994, 17, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Expression of mu-, kappa- and delta-opioid receptors in P19 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. Neuroscience 1999, 92, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Vega, F.M.; Isaac, H.I.; Scafe, C.R. A tool for selecting SNPs for association studies based on observed linkage disequilibrium patterns. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2006, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gelernter, J.; Gruen, J.R.; Kranzler, H.R.; Herman, A.I.; Simen, A.A. Functional impact of a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the OPRD1 promoter region. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 55, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, P.; Nothen, M.M.; Wang, T.; Neidt, H.; Knapp, M.; Lichtermann, D.; Weiffenbach, O.; Mayer, P.; Hollt, V.; Propping, P.; et al. Human delta-opioid receptor gene and susceptibility to heroin and alcohol dependence. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 88, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, P.; Rochlitz, H.; Rauch, E.; Rommelspacher, H.; Hasse, H.E.; Schmidt, S.; Hollt, V. Association between a delta opioid receptor gene polymorphism and heroin dependence in man. Neuroreport 1997, 8, 2547–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wei, L.N.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene by CpG methylation: Involvement of Sp3 and a methyl-CpG-binding protein, MBD2, in transcriptional repression of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene in Neuro2A cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 40550–40556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, G.; Liu, T.; Wei, L.N.; Law, P.Y.; Loh, H.H. DNA methylation-related chromatin modification in the regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Chang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, D.; Xu, X.; Cui, W.; Hong, Q.; Jiang, L.; et al. Elevated OPRD1 promoter methylation in Alzheimer’s disease patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.L.; Law, P.Y.; Loh, H.H. Sustained activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/nuclear factor kappaB signaling mediates G protein-coupled delta-opioid receptor gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 3067–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.L.; Law, P.Y.; Loh, H.H. NGF/PI3K signaling-mediated epigenetic regulation of delta opioid receptor gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 368, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.L.; Law, P.Y.; Loh, H.H. Action of NF-kappaB on the delta opioid receptor gene promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 352, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene. Role of Ikaros in the stimulated transcription of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene in activated T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 12854–12860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene. Ikaros-2 and upstream stimulatory factor synergize in trans-activating mouse delta-opioid receptor gene in T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 2304–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smirnov, D.; Im, H.J.; Loh, H.H. delta-Opioid receptor gene: Effect of Sp1 factor on transcriptional regulation in vivo. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene: Role of Ets-1 in the transcriptional activation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 45462–45469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.C.; Shen, J.T.; Augustin, L.B.; Ko, J.L.; Loh, H.H. Transcriptional regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 23617–23626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Woltje, M.; Kraus, J.; Hollt, V. Regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene transcription: Involvement of the transcription factors AP-1 and AP-2. J. Neurochem. 2000, 74, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.Y.; Hsu, T.I.; Chuang, J.Y.; Su, T.P.; Chang, W.C.; Hung, J.J. Sp1 in Astrocyte Is Important for Neurite Outgrowth and Synaptogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giros, B.; Pohl, M.; Rochelle, J.M.; Seldin, M.F. Chromosomal localization of opioid peptide and receptor genes in the mouse. Life Sci. 1995, 56, PL369–PL375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, C.A.; Filie, J.; Adamson, M.C.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L. Murine chromosomal location of the mu and kappa opioid receptor genes. Genomics 1994, 21, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, M.; Takeshima, H.; Mori, M.; Nakagawara, K.; Takeuchi, T. Structure and chromosomal mapping of genes for the mouse kappa-opioid receptor and an opioid receptor homologue (MOR-C). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 205, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Cao, S.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Promoter activity of mouse kappa opioid receptor gene in transgenic mouse. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1999, 69, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Hu, X.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Regulation of mouse kappa opioid receptor gene expression by retinoids. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 1590–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, S.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Studies of dual promoters of mouse kappa-opioid receptor gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997, 52, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, L.N.; Law, P.Y.; Loh, H.H. Post-transcriptional regulation of opioid receptors in the nervous system. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, L.N.; Hu, X.; Bi, J.; Loh, H. Post-transcriptional regulation of mouse kappa-opioid receptor expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000, 57, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Bi, J.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Regulation of mouse kappa opioid receptor gene expression by different 3′-untranslated regions and the effect of retinoic acid. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 62, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, J.Y.; Gu, X.; Liang, L.; Wu, S.; Mo, K.; Feng, J.; Guo, W.; Zhang, J.; Bekker, A.; et al. Nerve injury-induced epigenetic silencing of opioid receptors controlled by DNMT3a in primary afferent neurons. Pain 2017, 158, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannas, A.S.; Kim, J.H.; West, A.E. Regulation and function of MeCP2 Ser421 phosphorylation in U50488-induced conditioned place aversion in mice. Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebert, D.H.; Gabel, H.W.; Robinson, N.D.; Kastan, N.R.; Hu, L.S.; Cohen, S.; Navarro, A.J.; Lyst, M.J.; Ekiert, R.; Bird, A.P.; et al. Activity-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2 threonine 308 regulates interaction with NCoR. Nature 2013, 499, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.W.; He, Y.; Ha, S.G.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Epigenetic regulation of kappa opioid receptor gene in neuronal differentiation. Neuroscience 2008, 151, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.W.; Huq, M.D.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Retinoic acid-induced chromatin remodeling of mouse kappa opioid receptor gene. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 3350–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaisher-Grinberg, S.; Persaud, S.D.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Stress-induced epigenetic regulation of kappa-opioid receptor gene involves transcription factor c-Myc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9167–9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maiya, R.; Pomrenze, M.B.; Tran, T.; Tiwari, G.R.; Beckham, A.; Paul, M.T.; Dayne Mayfield, R.; Messing, R.O. Differential regulation of alcohol consumption and reward by the transcriptional cofactor LMO4. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2175–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestler, E.J. Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2012, 10, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shu, C.; Sosnowski, D.W.; Tao, R.; Deep-Soboslay, A.; Kleinman, J.E.; Hyde, T.M.; Jaffe, A.E.; Sabunciyan, S.; Maher, B.S. Epigenome-wide study of brain DNA methylation following acute opioid intoxication. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2021, 221, 108658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, N.P.; Bi, J.; Wei, L.N. The adaptor Grb7 links netrin-1 signaling to regulation of mRNA translation. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Li, J.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. A novel signaling pathway of nitric oxide on transcriptional regulation of mouse kappa opioid receptor gene. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 7941–7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.W.; Wei, L.N. Regulation of c-myc gene by nitric oxide via inactivating NF-kappa B complex in P19 mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 29776–29782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Park, S.W.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. Induction of the mouse kappa-opioid receptor gene by retinoic acid in P19 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 39967–39972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, X.; Bi, J.; Loh, H.H.; Wei, L.N. An intronic Ikaros-binding element mediates retinoic acid suppression of the kappa opioid receptor gene, accompanied by histone deacetylation on the promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 4597–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, G.; Ito, E.; Maruyama, K.; Pietruck, C.; Sharma, M.; Yu, L.; Pierce Palmer, P. An alternatively spliced transcript of the rat nociceptin receptor ORL1 gene encodes a truncated receptor. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2000, 77, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, B.; Nymberg, C.; Vuoksimaa, E.; Lourdusamy, A.; Wong, C.P.; Carvalho, F.M.; Jia, T.; Cattrell, A.; Macare, C.; Banaschewski, T.; et al. Association of Protein Phosphatase PPM1G With Alcohol Use Disorder and Brain Activity During Behavioral Control in a Genome-Wide Methylation Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Kranzler, H.R.; Zhao, H.; Gelernter, J. Profiling of childhood adversity-associated DNA methylation changes in alcoholic patients and healthy controls. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65648. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Choi, W.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.J. The regulatory mechanisms of intragenic DNA methylation. Epigenomics 2015, 7, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggeri, B.; Macare, C.; Stopponi, S.; Jia, T.; Carvalho, F.M.; Robert, G.; Banaschewski, T.; Bokde, A.L.W.; Bromberg, U.; Buchel, C.; et al. Methylation of OPRL1 mediates the effect of psychosocial stress on binge drinking in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Briant, J.A.; Nielsen, D.A.; Proudnikov, D.; Londono, D.; Ho, A.; Ott, J.; Kreek, M.J. Evidence for association of two variants of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor gene OPRL1 with vulnerability to develop opiate addiction in Caucasians. Psychiatr. Genet. 2010, 20, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Young, B.; Pletcher, M.T.; Heilig, M.; Wahlestedt, C. Association between the nociceptin receptor gene (OPRL1) single nucleotide polymorphisms and alcohol dependence. Addict. Biol. 2008, 13, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuei, X.; Flury-Wetherill, L.; Almasy, L.; Bierut, L.; Tischfield, J.; Schuckit, M.; Nurnberger, J.I., Jr.; Foroud, T.; Edenberg, H.J. Association analysis of genes encoding the nociceptin receptor (OPRL1) and its endogenous ligand (PNOC) with alcohol or illicit drug dependence. Addict. Biol. 2008, 13, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Sun, L.; Xiao, J.; Su, S.; Du, S.; Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Mo, K.; et al. N(6)-Methyladenosine Demethylase FTO Contributes to Neuropathic Pain by Stabilizing G9a Expression in Primary Sensory Neurons. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.R.; Kramar, E.A.; Pham, L.; Beardwood, J.H.; Augustynski, A.S.; Lopez, A.J.; Chitnis, O.S.; Delima, G.; Banihani, J.; Matheos, D.P.; et al. HDAC3 Activity within the Nucleus Accumbens Regulates Cocaine-Induced Plasticity and Behavior in a Cell-Type-Specific Manner. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 2814–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesch, J.; Zwick, A.; Garz, A.K.; Palau, A.; Buschbeck, M.; Gotze, K.S. A clinical-molecular update on azanucleoside-based therapy for the treatment of hematologic cancers. Clin. Epigenet. 2016, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marks, P.A.; Breslow, R. Dimethyl sulfoxide to vorinostat: Development of this histone deacetylase inhibitor as an anticancer drug. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricken, R.; Ulrich, S.; Schlattmann, P.; Adli, M. Tranylcypromine in mind (Part II): Review of clinical pharmacology and meta-analysis of controlled studies in depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, L.; Wang, R.; Shi, L. BET inhibitors: An updated patent review (2018–2021). Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2022, 32, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, A.; Arimondo, P.B.; Rots, M.G.; Jeronimo, C.; Berdasco, M. The timeline of epigenetic drug discovery: From reality to dreams. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sales, A.J.; Biojone, C.; Terceti, M.S.; Guimaraes, F.S.; Gomes, M.V.; Joca, S.R. Antidepressant-like effect induced by systemic and intra-hippocampal administration of DNA methylation inhibitors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164, 1711–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keller, S.M.; Doherty, T.S.; Roth, T.L. Pharmacological manipulation of DNA methylation normalizes maternal behavior, DNA methylation, and gene expression in dams with a history of maltreatment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Athira, K.V.; Sadanandan, P.; Chakravarty, S. Repurposing Vorinostat for the Treatment of Disorders Affecting Brain. Neuromol. Med. 2021, 23, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcq, E.; Kieffer, B.L. Opioid receptors: Drivers to addiction? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.B.; Babigian, C.J.; Sartor, G.C. Domain-selective BET inhibition attenuates transcriptional and behavioral responses to cocaine. Neuropharmacology 2022, 210, 109040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, G.A.; Singh, H.; Dang, R.; Wood, M.A. HDAC3 is a negative regulator of cocaine-context-associated memory formation. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 6623–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malvaez, M.; Mhillaj, E.; Matheos, D.P.; Palmery, M.; Wood, M.A. CBP in the nucleus accumbens regulates cocaine-induced histone acetylation and is critical for cocaine-associated behaviors. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 16941–16948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.J.; Feng, J.; Robison, A.J.; Maze, I.; Badimon, A.; Mouzon, E.; Chaudhury, D.; Damez-Werno, D.M.; Haggarty, S.J.; Han, M.H.; et al. Class I HDAC inhibition blocks cocaine-induced plasticity by targeted changes in histone methylation. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.W.; Huang, T.L.; Tsai, M.C. Decreased Level of Blood MicroRNA-133b in Men with Opioid Use Disorder on Methadone Maintenance Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug | Treatment | MOR | DOR | KOR | NOP | Related Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | Acute treatment (sample collection within 20-120 min) | No change in Oprm1 mRNA (rat) | N/A | No change in Oprk1 mRNA (rat) | No change in Oprl1 mRNA (rat) | ↓ transcript levels of DNMT1, DNMT3a, TET1, and TET2 (mouse) ↓ miR-124 in NAc (mouse) | [66,114,115] |

| Chronic treatment with short-term withdrawal period (30 min) | ↑ Oprm1 mRNA in NAc (rat) | No change in Oprd1 mRNA (rat) | ↓ Oprk1 mRNA in SN, VTA, and NAc (rat) | N/A | ↑ NF-κB subunits in NAc (mouse) ↑ ΔFosB in NAc (human) ↑ MEG3 (mouse HT22 cels in vitro) ↑ 5-mC levels in NAc (rat) ↑ DNMT transcripts and enzyme activity (mouse) ↓ H3K9me2 in NAc (mouse) ↓ PRMT6 and H3R2me2a in NAc (mouse) ↓ SOX2 (human NPCs) ↓ miR-124 in NAc (mouse) | [98,116,117,118,119,120,121,122] | |

| Chronic treatment with long-term withdrawal period (≥24 h) | ↑ Oprm1 mRNA in frontal cortex (rat) ↑ Oprm1 mRNA in NAc (rat) | ↑ Oprd1 mRNA in CPu (rat) No change in Oprd1 mRNA in NAc (rat) | ↑ Oprk1 mRNA in CPu (rat) No change in Oprk1 mRNA in NAc (rat) | ↑ Oprl1 mRNA in NAc (rat) ↓ Oprl1 mRNA in lateral CPu (rat) | [66,79,80,115,123,124,125,126,127] | ||

| METH and MDMA | Acute treatment (sample collection within 20–120 min) | No change in Oprm1 mRNA (rat) | N/A | No change in Oprk1 mRNA (rat) | ↓ Oprl1 mRNA in NAc by MDMA (rat) | ↑ miR-181a-5p in NAc (rat) ↓ c-Fos in brain (male mouse) | [32,128,129] |

| Chronic treatment with long-term withdrawal period (≥24 h) | ↑ Oprm1 mRNA (mouse) | No change in Oprd1 mRNA (mouse) | ↑ Oprk1 mRNA in NAc (rat) No change in Oprk1 mRNA (mouse) | ↓ Oprl1 mRNA in NAc by MDMA (rat) | ↑ miR-143 in blood (human) ↓ miR-496-3p, miR-194-5p, and miR-200-3p in NAc (rat) ↑ c-Fos in amygdala (mouse) ↓ CREB in hippocampus (rat) ↓ BDNF in hippocampus (rat) | [32,89,128,130,131,132] | |

| Alcohol | Chronic treatment with long-term withdrawal period (≥24 h) | ↑ Oprm1 mRNA in striatum (mouse), NAc and amygdala (rat) | ↑ Oprd1 mRNA in VTA and NAc (mouse) | ↑ Oprk1 mRNA in NAc (rat and mouse) | ↓ Oprl1 mRNA in NAc (rat) | ↑ USF, AP2, and Ets1 in CeA (rat) ↑ DNMTs transcription and activity in NAc (rat) ↑ Global 5-mC and 5-hmC in NAc (rat) ↑ c-Fos in amygdala and hippocampus (rat) | [133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140] |

| Opioids Fentanyl | Chronic treatment with long-term withdrawal period (≥24 h) | ↑ Oprm1 mRNA in PC12 cells (rat, in vitro) | No change in Oprd1 mRNA in dorsal horn (mouse) | N/A | No change in Oprl1 mRNA in SH-SY5Y cells (human in vitro) | ↑ miR-339-3p in hippocampal neurons (mouse) | [88,141,142,143] |

| Heroin | Chronic treatment with long-term withdrawal period (≥24 h) | ↓ Oprm1 mRNA in NAc (rat) | N/A | N/A | N/A | ↑ association of SNPs: rs2236861, rs2236857 and rs3766951) at intron 1 of OPRD1 (human) ↑ H3K27ac in the striatum (human) | [72,144,145] |

| Morphine | Chronic treatment with a long-term withdrawal period (≥24 h) | No change in Oprm1 mRNA in PC12 cells (rat) ↓ Oprm1 mRNA in PAG (rat in vitro) ↓ Oprm1 mRNA in SH-SY5Y cells (human in vitro) | ↑ Oprd1 mRNA in the spinal cord (rat) ↓ Oprd1 mRNA in PAG (rat) | ↑ Oprk1 mRNA in the spinal cord (rat) | ↓ Oprl1 mRNA in SH-SY5Y cells (human in vitro) | ↑ miR-339-3p in hippocampal neurons (mouse) ↑ miR-23b in N2A cells (mouse in vitro) ↑ MRAK159688 expression (rat) ↑ AP-2 in the hippocampal postsynaptic density (mouse) ↑ H3K27ac in spinal dorsal horn (mouse) ↑ ∆FosB binding at dynorphin promoter in NAc (mouse) ↑ NF-κB expression in neuronal cells (human in vitro) | [88,141,142,146,147,148,149,150,151,152] |

| Oxycodone | Acute treatment (sample collection within 20–120 min) | ↑ Oprm1 mRNA in the spinal cord (rat) | No change in Oprd1 mRNA in the spinal cord (rat) | No change in Oprk1 mRNA in the spinal cord (rat) | N/A | N/A | [153] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reid, K.Z.; Lemezis, B.M.; Hou, T.-C.; Chen, R. Epigenetic Modulation of Opioid Receptors by Drugs of Abuse. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11804. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911804

Reid KZ, Lemezis BM, Hou T-C, Chen R. Epigenetic Modulation of Opioid Receptors by Drugs of Abuse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(19):11804. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911804

Chicago/Turabian StyleReid, Ke Zhang, Brendan Matthew Lemezis, Tien-Chi Hou, and Rong Chen. 2022. "Epigenetic Modulation of Opioid Receptors by Drugs of Abuse" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 19: 11804. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911804

APA StyleReid, K. Z., Lemezis, B. M., Hou, T.-C., & Chen, R. (2022). Epigenetic Modulation of Opioid Receptors by Drugs of Abuse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(19), 11804. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911804