Abstract

Mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I) is a rare monogenic disease in which glycosaminoglycans’ abnormal metabolism leads to the storage of heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate in various tissues. It causes its damage and impairment. Patients with the severe form of MPS I usually do not live up to the age of ten. Currently, the therapy is based on multidisciplinary care and enzyme replacement therapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Applying gene therapy might benefit the MPS I patients because it overcomes the typical limitations of standard treatments. Nanoparticles, including nanoemulsions, are used more and more in medicine to deliver a particular drug to the target cells. It allows for creating a specific, efficient therapy method in MPS I and other lysosomal storage disorders. This article briefly presents the basics of nanoemulsions and discusses the current state of knowledge about their usage in mucopolysaccharidosis type I.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Basics

Mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I, OMIM # 607014) is a rare monogenic disease belonging to the lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs). Severe MPS I occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 new-borns. Attenuated MPS I is less common and occurs in about 1/500,000. Prevalence is estimated at 1/100,000, with Hurler syndrome accounting for 57% of cases, Hurler-Scheie syndrome accounting for 23% of cases, and Scheie syndrome accounting for 20% of cases. It is caused by a mutation in the IDUA gene, causing α-L-iduronidase deficiency (IDUA) and is inherited in an autosomal recessive way (gene locus 4p16.3) [1,2,3]. The most common mutation found in the European and South American populations is c.1205G>A (p.Trp402∗), resulting in the introduction of the STOP codon and premature transcription termination. It is related to the very severe phenotype of the disease [4]. The lysosomal hydrolase defect disrupts the degradation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), heparan sulfate (HS), and dermatan sulfate (DS), resulting in the accumulation of mucopolysaccharides in mesenchymal tissues and lipids in nervous tissue.

There are three clinical forms of this disease:

- -

- severe—Hurler syndrome (MPS IH, OMIM #607014),

- -

- moderate—Hureler-Scheie syndrome (MPS IH/S, OMIM #607015),

- -

- mild—Scheie syndrome (MPS IS, OMIM #607016) [2,5].

The severe phenotype of the disease was first described by Gertrud Hurler in 1919 [6]. In 1962, Scheie et al. published a report on a milder form of the disease [7]. The moderate phenotype was characterised in 1976 by Stevenson et al. [8].

1.2. Clinical Features

All three forms of type I mucopolysaccharidosis differ in their clinical course and symptom severity. However, there are common features present in all forms of the disease: corneal clouding, a low bone ridge of the nose (flat base and bridge of the nose with wide, flat nostrils), thickened lips, aortic and mitral valve abnormalities, obstructive airway diseases, changes in the skeletal system known as dysostosis multiplex, and urinary excretion of dermatan sulfate and heparan sulfate. In Hurler syndrome, the first changes can already be observed in the first six months of life in the form of a mild facial dysmorphia, a macrocephaly, and limited mobility in the hip joints. There are frequent respiratory system infections. After the age of 6 months, the growth rate slows down, and a progressive intellectual disability is observed. The typical phenotype of a patient with this form of MPS I includes clinical symptoms that increase over time, such as short stature, coarse facial features, full cheeks, gingival hyperplasia, tongue enlargement, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, joint contracture, premature overgrowth of the sagittal and frontal suture, and J-shaped sella turcica. Other symptoms observed in patients with Hurler syndrome are a tendency to hypertelorism, internal epicanthal folds, pigmentary retinal dystrophy, optic nerve compression and its atrophy, cortical visual impairment, open angle glaucoma, alveolar hypertrophy, macroglossia, short neck, kyphosis and thoracolumbar humps, underdevelopment of the odontoid process, enlargement of the shafts and deformation of the short bones, enlargement of the medial ends of the clavicles, hirsutism, hepatosplenomegaly, hernias (inguinal, umbilical), hip dislocation, tracheal stenosis, spinal cord and cranial nerves compression, and deafness [5]. Usually, breathing problems or heart failure lead to death in childhood. Hurler patients rarely live to the age of 10. In the moderate form of the disease—Hurler-Scheie syndrome—symptoms occur between 3 and 8 years of age, and patients usually live up to 20 years. Symptoms of the disease may be similar to the severe form, but the intellectual disability is mild, and the image of the coarse face is not as intense. Patients with Scheie syndrome may have normal intellectual development, and the first symptoms are not found until the second and third decades of life. Patients may develop eye damage or skeletal abnormalities limiting physical ability, while the life expectancy does not differ from the average value for the population [5,9,10]. The sporadic abnormalities seen in MPS I patients include hydrocephalus, probably due to thickening of the cerebral meninges, arachnoid cysts, hydrocoele, nephritic syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, bent thumb, and hypotrophy of the condylar process of the mandible [5].

1.3. Diagnosis and Management

The diagnosis confirmation is based on the presence of increased levels of dermatan sulphate and heparan sulphate in the urine and the absence of α-L-iduronidase activity in peripheral blood leukocytes or skin fibroblasts. Prenatal diagnosis is possible by assessing the enzyme activity in the cells of the amniotic fluid and detecting the mutation in the material from amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling [5]. Molecular methods are used to determine the mutation in the IDUA gene and evaluate its significance [10].

The therapeutic possibilities of MPS I are limited and rely on multidisciplinary care, but scientists are still attempting to apply new curative methods. Thanks the discovery of the phenomenon of cross-correction, i.e., the secretion of the enzyme by some cells and its uptake by others via the mannose-6-phosphate receptor, the work on obtaining therapeutic agents was accelerated [11,12]. Currently, an enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) using recombinant human α-L-iduronidase administered intravenously is mainly used. It effectively inhibits liver enlargement and improves mobility in joints, respiratory capacity, and heart function. However, the enzyme cannot cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) by itself, so this method does not correct the function of the central nervous system (CNS). Another available treatment is hematopoietic stem cell (HSCT) transplantation, which has been successful when applied before the age of 24 months. The transplantation generally increases survival by 67%. This procedure prevents the coarsening of facial features and enlargement of the liver and spleen and improves hearing, respiratory and heart function. Children who have undergone transplantation before the age of 24 months and who score 70 or more points on the Mental Developmental Index scale may show beneficial neural and behavioural development. Despite this, progression of valvular insufficiency, skeletal abnormalities, and corneal clouding are often found. [5,13,14]. However, this procedure carries a risk of complications due to the immunosuppressive therapy and the graft versus host disease (GvHD).

Researchers attempt to overcome these difficulties by using new techniques, including gene therapy. Gene therapy refers to the use of nucleic acids to treat/modify the course of disease in humans. Due to the used carrier of the reconstructed genetic information, it can be divided into virus-based and non-viral gene therapy. In the first case, the correct gene or genome editing system is delivered by a virus. The first ever attempt at gene therapy took place almost 30 years ago in severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency [15]. The first vectors used in this treatment method were retroviruses and lentiviruses. However, they were characterised by limitations (random integration with the genome and immunogenicity) that reduced their usefulness. Nowadays, there are usually used adenovirus-associated viruses (AAVs), ensuring a broad and stable gene expression. Still, it is associated with the risk of immunogenicity and mutagenesis. An alternative is the use of non-viral vectors, e. g., nanoparticles or the Sleeping Beauty transposon system [16,17,18]. These methods do not have the limitations of viruses and are being developed more and more. In the following part of the review, we would like to present the current possibilities of gene therapy using nanoemulsions in mucopolysaccharidosis type I.

3. Challenges and Perspective

Gene therapy is a promising and continuously developed method of treating monogenic diseases. It was first used in humans in the early 1990s in severe combined immunodeficiency associated with adenosine deaminase deficiency [15]. Since then, a lot of progress has been made in this area. Viral vectors have significant limitations related to immunogenicity and the mutagenesis risk (retroviruses, lentiviruses). Antibodies are produced to a lesser extent against AAVs, making them the most optimal viral vector nowadays [34]. In addition to the virus as a vector, elements of the genome editing systems may also be immunogenic [35]. This effect is minor with nanoemulsions, and it is their main advantage. In addition, they are easy to obtain; they can be combined with various molecules; and, with appropriate modifications, they can easily cross biological barriers.

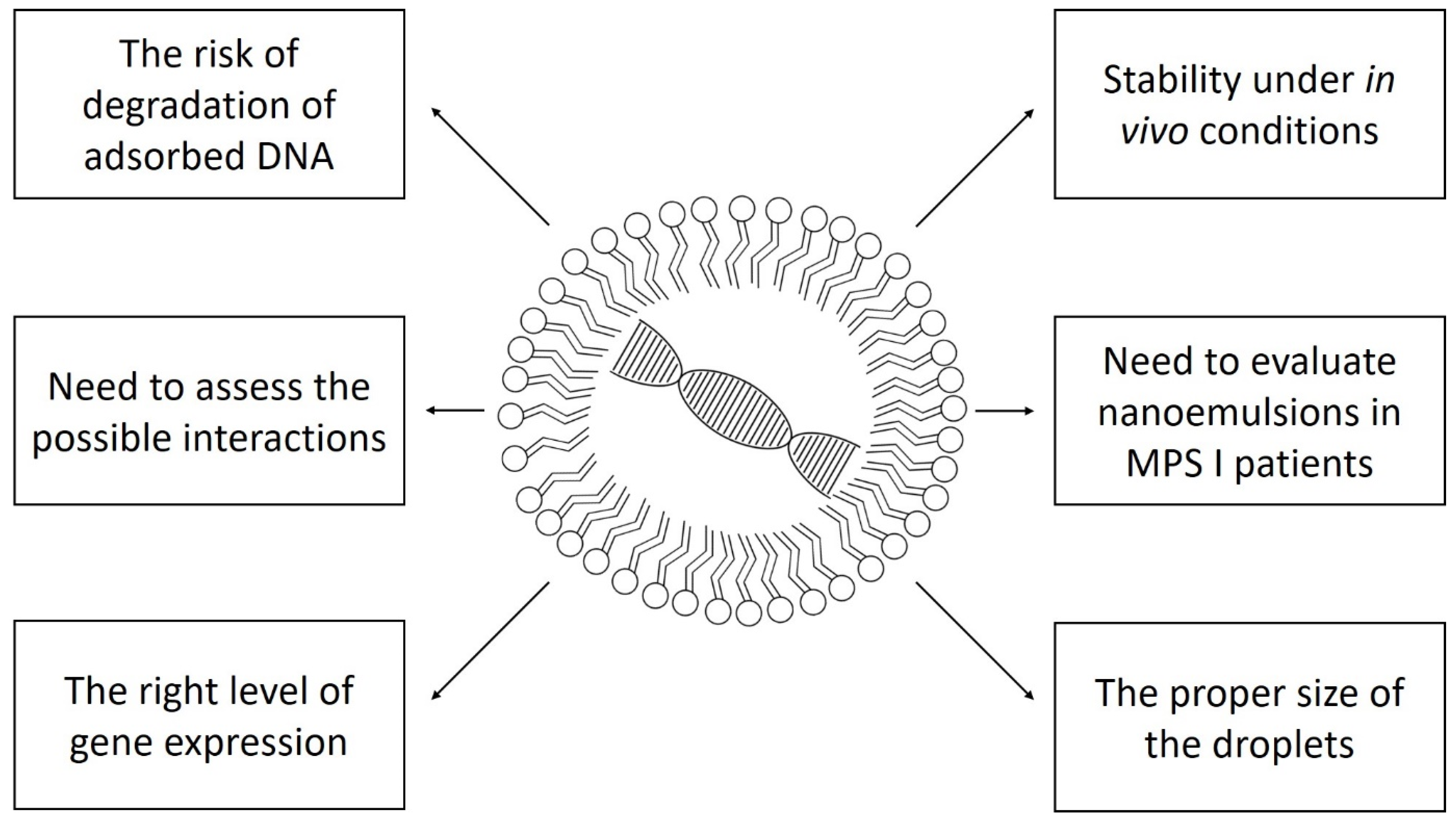

Despite all their advantages, nanoemulsions have limitations, and there are still many challenges for researchers to overcome. First, all available studies as of today have been performed on cell lines or laboratory organisms. Even the best model of mucopolysaccharidosis type I will not reflect the actual conditions in the human body. The intravenous solution itself may prove less stable in vivo, and plasma enzymes may degrade the conjugated DNA. The true expression of the gene in target cells is also difficult to predict.

Due to the lack of data on the use of nanoemulsions in mucopolysaccharidosis type I in humans, further studies, including randomised clinical trials, are needed to assess the safety and effectiveness of such therapy. It is also necessary to analyse possible interactions in the human body and identify factors influencing the efficacy of in vivo transfection.

Clinical trials with gene therapy are conducted in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type I. However, they are based on viral vectors or autologous transplantation of modified CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells [36]. Nanoemulsions used with various drugs are applied in clinical trials in neoplastic, ophthalmological, dermatological, and haematological diseases. So far, there are no registered clinical studies using nanoemulsions in storage diseases, including mucopolysaccharidoses [37]. Figure 1 shows schematically the problems that must be solved to safely and effectively use nanoemulsion gene therapy in humans.

Figure 1.

The most important problems standing in the way to the widespread use of nanoemulsion gene therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis type I.

4. Conclusions

Mucopolysaccharidosis type I, as a monogenic disease, is the optimal target of gene therapy. So far, therapeutic possibilities are limited to multidisciplinary care and enzyme replacement therapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clinical trials with the use of gene therapy based on viral vectors are underway. Despite numerous studies in cell cultures and animal models, no attempts have been made to use nanoemulsions as a vector for genetic transfer in MPS I patients. The further development of molecular biology methods and the improvement of non-viral carriers will probably contribute to the application of this type of gene therapy also in humans. More studies are needed to assess the safety and efficacy of these agents in animals. Additionally, the first clinical studies in patients with Hurler syndrome are necessary. The combined use of viral and non-viral vectors could also be considered to increase the current knowledge. Possibly, the initiation of an additional branch of research on model organisms or clinical trials in patients with Hurler syndrome would provide new information on the effectiveness of different ways of delivering the gene to the target cells. Such studies could compare the use of other vectors and their routes of delivery into the body. Such activities could undoubtedly accelerate the achievement of an effective method of treatment, including the improvement of the central nervous system functions. This will directly translate into the development and quality of life of the patients.

Author Contributions

P.Z. conceived of the idea; P.Z. wrote the manuscript and prepared the table and the figure; A.P. supervised the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat |

| DOTAP | 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-trimethylammonium propane |

| DS | Dermatan sulphate |

| ERT | Enzyme replacement therapy |

| FLS | Fibroblast-like synoviocytes |

| GAGs | Glycosaminoglycans |

| GvHD | Graft versus host disease |

| HS | Heparan sulphate |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| IDUA | Alpha-L-iduronidase |

| LSDs | Lysosomal storage disorders |

| MPS I | Mucopolysaccharidosis type I |

| PUFA | Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| Trp | Tryptophan |

References

- Orpha.net. Mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=GB&Expert=579 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Available online: https://www.omim.org/entry/607014 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- MedlinePlus. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/mucopolysaccharidosis-type-i/#frequency (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Matte, U.; Yogalingam, G.; Brooks, D.; Leistner, S.; Schwartz, I.; Lima, L.; Norato, D.Y.; Brum, J.M.; Beesley, C.; Winchester, B.; et al. Identification and characterization of 13 new mutations in mucopolysaccharidosis type I patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2003, 78, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.L.; Jones, M.C.; Del Campo, M. Atlas Malformacji Rozwojowych Według Smitha; MediPage: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; pp. 596–599. [Google Scholar]

- Hurler, G. Über einen Typ multipler Abartungen, vorwiegend am Skelettsystem. Z. Kinder-Heilk. 1920, 24, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheie, H.G.; Hambrick, G.W., Jr.; Barness, L.A. A newly recognized forme fruste of Hurler’s disease (gargoylism). Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1962, 53, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, R.E.; Howell, R.R.; McKusick, V.A.; Suskind, R.; Hanson, J.W.; Elliott, D.E.; Neufeld, E.F. The iduronidase-deficient mucopolysaccharidoses: Clinical and roentgenorgraphic features. Pediatrics 1976, 57, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Available online: https://www.omim.org/clinicalSynopsis/table?mimNumber=253010,601492,607016,607015,607014,253200,253220,252930,253000,252920,252900,309900 (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Giugliani, R. Mucopolysacccharidoses: From understanding to treatment, a century of discoveries. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2012, 35, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratantoni, J.C.; Hall, C.W.; Neufeld, E.F. Hurler and Hunter syndromes: Mutual correction of the defect in cultured fibroblasts. Science 1968, 162, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasilik, A.; Neufeld, E.F. Biosynthesis of lysosomal enzymes in fibroblasts. Phosphorylation of mannose residues. J. Biol. Chem. 1980, 255, 4946–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliani, R.; Federhen, A.; Rojas, M.V.M.; Vieira, T.; Artigalás, O.; Pinto, L.L.; Azevedo, A.C.; Acosta, A.; Bonfim, C.; Lourenço, C.M.; et al. Mucopolysaccharidosis I, II, and VI: Brief review and guidelines for treatment. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2010, 33, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollak, C.E.; Wijburg, F.A. Treatment of lysosomal storage disorders: Successes and challenges. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014, 37, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaese, R.M.; Culver, K.W.; Miller, A.D.; Carter, C.S.; Fleisher, T.; Clerici, M.; Shearer, G.; Chang, L.; Chiang, Y.; Tolstoshev, P.; et al. T lymphocyte-directed gene therapy for ADA-SCID: Initial trial results after 4 years. Science 1995, 270, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, K.B.; Büning, H.; Galy, A.; Schambach, A.; Grez, M. Gene therapy on the move. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 1642–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapolnik, P.; Pyrkosz, A. Gene Therapy for Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II-A Review of the Current Possibilities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuh, R.S.; de Carvalho, T.G.; Giugliani, R.; Matte, U.; Baldo, G.; Teixeira, H.F. Gene editing of MPS I human fibroblasts by co-delivery of a CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid and a donor oligonucleotide using nanoemulsions as nonviral carriers. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 122, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Yu, S.Y. Cationic nanoemulsions as non-viral vectors for plasmid DNA delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 79, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, T.; Liu, F.; Liu, D.; Huang, L. Emulsion formulations as a vector for gene delivery in vitro and in vivo. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 24, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Meher, J.G.; Raval, K.; Khan, F.A.; Chaurasia, M.; Jain, N.K.; Chourasia, M.K. Nanoemulsion: Concepts, development and applications in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 252, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.; Panghal, A.; Flora, S.J.S. Nanotechnology: A Promising Approach for Delivery of Neuroprotective Drugs. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.Y.; Guo, P.; Wen, W.C.; Wong, H.L. Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for RNA Delivery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 3140–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, L.; Yadav, S.; Amiji, M. Nanotechnology for CNS delivery of bio-therapeutic agents. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2013, 3, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazylińska, U.; Saczko, J. Nanoemulsion-templated polylelectrolyte multifunctional nanocapsules for DNA entrapment and bioimaging. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 137, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.A.; Chan, M.; Shaw, C.A.; Hekele, A.; Carsillo, T.; Schaefer, M.; Archer, J.; Seubert, A.; Otten, G.R.; Beard, C.W.; et al. A cationic nanoemulsion for the delivery of next-generation RNA vaccines. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, H.Y.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.; Kwon, I.C.; Jeong, S.Y. Lipid-based emulsion system as non-viral gene carriers. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009, 32, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, H.F.; Bruxel, F.; Fraga, M.; Schuh, R.S.; Zorzi, G.K.; Matte, U.; Fattal, E. Cationic nanoemulsions as nucleic acids delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 534, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, M.; Bruxel, F.; Diel, D.; de Carvalho, T.G.; Perez, C.A.; Magalhães-Paniago, R.; Malachias, Â.; Oliveira, M.C.; Matte, U.; Teixeira, H.F. PEGylated cationic nanoemulsions can efficiently bind and transfect pIDUA in a mucopolysaccharidosis type I murine model. J. Control. Release 2015, 209, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, M.; de Carvalho, T.G.; Bidone, J.; Schuh, R.S.; Matte, U.; Teixeira, H.F. Factors influencing transfection efficiency of pIDUA/nanoemulsion complexes in a mucopolysaccharidosis type I murine model. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fraga, M.; Schuh, R.S.; Poletto, É.; de Carvalho, T.G.; França, R.T.; Pinheiro, C.V.; Baldo, G.; Giugliani, R.; Teixeira, H.F.; Matte, U. Gene Therapy of Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I Mice: Repeated Administrations and Safety Assessment of pIDUA/Nanoemulsion Complexes. Curr. Gene Ther. 2021, 21, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidone, J.; Schuh, R.S.; Farinon, M.; Poletto, É.; Pasqualim, G.; de Oliveira, P.G.; Fraga, M.; Xavier, R.M.; Baldo, G.; Teixeira, H.F.; et al. Intra-articular nonviral gene therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis I mice. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 548, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, R.S.; Bidone, J.; Poletto, E.; Pinheiro, C.V.; Pasqualim, G.; de Carvalho, T.G.; Farinon, M.; da Silva Diel, D.; Xavier, R.M.; Baldo, G.; et al. Nasal Administration of Cationic Nanoemulsions as Nucleic Acids Delivery Systems Aiming at Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I Gene Therapy. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutin, S.; Monteilhet, V.; Veron, P.; Leborgne, C.; Benveniste, O.; Montus, M.F.; Masurier, C. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: Implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, E.; Baldo, G.; Gomez-Ospina, N. Genome Editing for Mucopolysaccharidoses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Mucopolysaccharidosis+I+gene+therapy&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=nanoemulsion&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 1 December 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).