Increased Expression of Orexin-A in Patients Affected by Polycystic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Anthropometric, Biochemical and Clinical Features

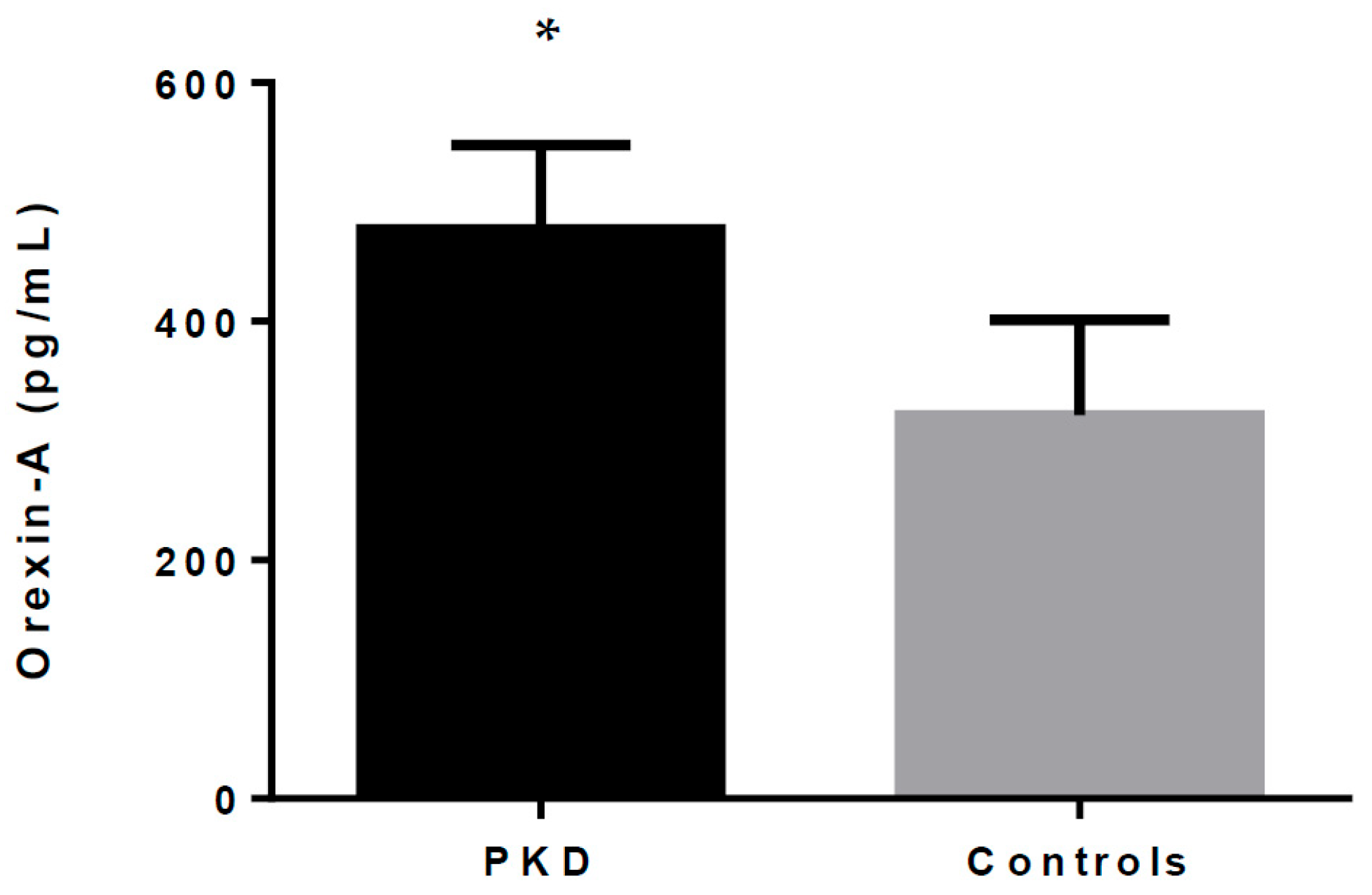

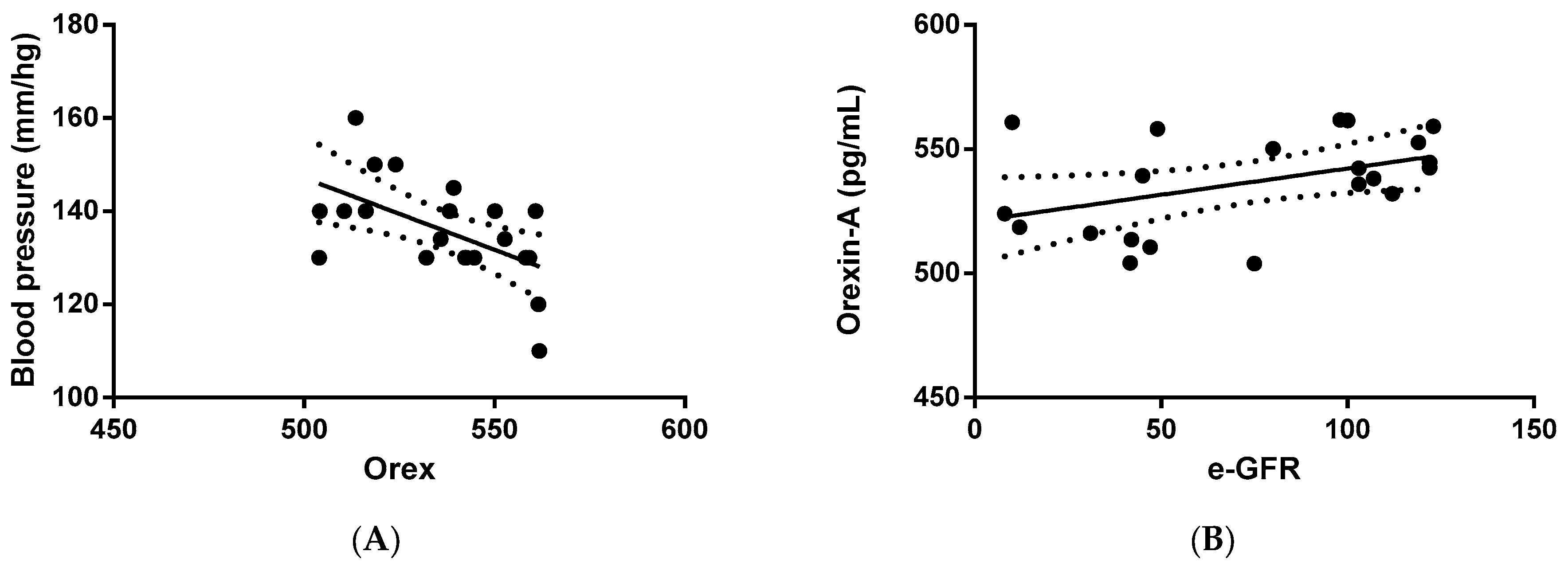

2.2. Orexin-A Levels Are Statistically Higher in PKD Patients Than Controls, Inversely Correlates with Blood Pressure and Directly with eGFR

2.3. HCRT SNPs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Participants

4.2. ELISA Assay

4.3. SNPs: Sanger Sequencing

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chow, L.C.; Ong, A.C.M. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin. Med. 2009, 9, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornec-Le Gall, E.; Audrézet, M.P.; Chen, J.M.; Hourmant, M.; Morin, M.P.; Perrichot, R.; Charasse, C.; Whebe, B.; Renaudineau, E.; Jousset, P.; et al. Type of PKD1 mutation influences renal outcome in ADPKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecder, T.; Schrier, R.W. Cardiovascular abnormalities in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2009, 5, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, E.; Amicone, M.; D’Arco, D.; Sellitti, G.; De Marco, O.; Guarino, M.; Riccio, E.; Pisani, A.; Daniele, A. Molecular Diagnosis and Identification of Novel Pathogenic Variants in a Large Cohort of Italian Patients Affected by Polycystic Kidney Diseases. Genes 2023, 14, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordido, A.; Besada-Cerecedo, L.; Gonzalez, M.A.G. The Genetic and Cellular Basis of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease-A Primer for Clinicians. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldrop, E.; Al-Obaide, M.A.I.; Vasylyeva, T.L. GANAB and PKD1 Variations in a 12 Years Old Female Patient with Early Onset of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, V.E.; Harris, P.C.; Pirson, Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet 2007, 369, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisani, A.; Daniele, A.; Di Domenico, C.; Nigro, E.; Salvatore, F.; Riccio, E. Late diagnosis of Fabry disease caused by a de novo mutation in a patient with end stage renal disease. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.C.; Rossetti, S. Determinants of renal disease variability in ADPKD. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010, 17, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.B.; Stepniakowski, K.; Rahbari-Oskoui, F. Hypertension in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigalke, J.A.; Shan, Z.; Carter, J.R. Orexin, Sleep, Sympathetic Neural Activity, and Cardiovascular Function. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2643–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Blache, D.; Vercoe, P.E.; Adam, C.L.; Blackberry, M.A.; Findlay, P.A.; Eidne, K.A.; Martin, G.B. Expression of orexin receptors in the brain and peripheral tissues of the male sheep. Regul. Pept. 2005, 124, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, G.; Dalia, C.; Tafuri, D.; Monda, V.; Palmieri, F.; Dato, A.; Russo, A.; De Blasio, S.; Messina, A.; De Luca, V.; et al. Orexin-A controls sympathetic activity and eating behavior. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, M.J.; Chen, Q.-H.; Shan, Z. The Orexin System and Hypertension. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Nattie, E. Orexin, cardio-respiratory function, and hypertension. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Sakurai, T.; Fukuda, Y.; Kuwaki, T. Orexin neuron-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation and shift of baroreflex during defense response in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 290, R1654–R1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrive, P. Orexin, orexin receptor antagonists and central cardiovascular control. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-J.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.P. Upregulation of orexin receptor in paraventricular nucleus promotes sympathetic outflow in obese Zucker rats. Neuropharmacology 2015, 99, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Arihara, Z.; Suzuki, T.; Sone, M.; Kikuchi, K.; Sasano, H.; Murakami, O.; Totsune, K. Expression of orexin-A and orexin receptors in the kidney and the presence of orexin-A-like immunoreactivity in human urine. Peptides 2006, 27, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.D.; Xhaard, H.; Sakurai, T.; Rainero, I.; Kukkonen, J.P. OX1 and OX2 orexin/hypocretin receptor pharmacogenetics. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.D.; Comings, D.E.; Abu-Ghazalah, R.; Jereseh, Y.; Lin, L.; Wade, J.; Sakurai, T.; Tokita, S.; Yoshida, T.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Variants of the orexin2/hcrt2 receptor gene identified in patients with excessive daytime sleepiness and patients with Tourette’s syndrome comorbidity. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2004, 129B, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.A.; Tsutsumi, M.; Nakata, S.; Mori, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Kato, I.; Nakashima, M.; Kurahashi, H.; Suzuki, K. A functional variation in the hypocretin neuropeptide precursor gene may be associated with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in Japan. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Cao, C.; Fang, R.; Liu, P.; Luo, S.; Liberzon, I. The preliminary investigation of orexigenic hormone gene polymorphisms on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 100, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainero, I.; Rubino, E.; Gallone, S.; Fenoglio, P.; Picci, L.R.; Giobbe, L.; Ostacoli, L.; Pinessi, L. Evidence for an association between migraine and the hypocretin receptor 1 gene. J. Headache Pain 2011, 12, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, B.Y.; Lin, H.N.; Wang, M.C.; Ren, J.-X. A review of physiological functions of orexin: From instinctive responses to subjective cognition. Medicine 2023, 102, e34206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, H.; Umegaki, H.; Yanagawa, M.; Komiya, H.; Watanabe, K.; Kuzuya, M. Plasma orexin-A-like immunoreactivity levels and renal function in patients in a geriatric ward. Peptides 2019, 118, 170092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakabayashi, M.; Suzuki, T.; Takahashi, K.; Totsune, K.; Muramatsu, Y.; Kaneko, C.; Date, F.; Takeyama, J.; Darnel, A.D.; Moriya, T.; et al. Orexin-A expression in human peripheral tissues. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003, 205, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, E.; Mallardo, M.; Amicone, M.; D’Arco, D.; Riccio, E.; Marra, M.; Pasanisi, F.; Pisani, A.; Daniele, A. Exploring Adiponectin in Autosomal Dominant Kidney Disease: Insight and Implications. Genes 2024, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieminski, M.; Szypenbejl, J.; Partinen, E. Orexins, Sleep, and Blood Pressure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaba, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Kasuya, Y.; Ohuchi, T.; Yanagisawa, M.; Komuro, I.; Fukuda, Y.; Kuwaki, T. Attenuated defense response and low basal blood pressure in orexin knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003, 285, R581–R593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianini, S.; Silvani, A. Clinical Implications of Basic Research: The Role of Hypocretin/Orexin Neurons in the Central Autonomic Network. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2018, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadio, V.; Liguori, R.; Vandi, S.; Pizza, F.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Leta, V.; Giannoccaro, M.P.; Baruzzi, A.; Plazzi, G. Lower wake resting sympathetic and cardiovascular activities in narcolepsy with cataplexy. Neurology 2014, 83, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, T.; Nagake, Y.; Sugimoto, S.; Akagi, S.; Ichikawa, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Ogawa, N.; Makino, H. Plasma orexin concentrations in patients on hemodialysis. Nephron 2002, 90, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, S.; Iwata, Y.; Furuichi, K.; Sagara, A.; Shinozaki, Y.; Toyama, T.; Sakai, N.; Shimizu, M.; Sakurai, T.; Kaneko, S.; et al. Messenger RNA expression profile of sleep-related genes in peripheral blood cells in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2016, 20, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourier, C.; Ran, C.; Steinberg, A.; Sjöstrand, C.; Waldenlind, E.; Belin, A.C. Analysis of HCRTR2 Gene Variants and Cluster Headache in Sweden. Headache 2019, 59, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainero, J.; Gallone, S.; Valfrè, W.; Ferrero, M.; Angilella, G.; Rivoiro, C.; Rubino, E.; De Martino, P.; Savi, L.; Ferrone, M.; et al. A polymorphism of the hypocretin receptor 2 gene is associated with cluster headache. Neurology 2004, 63, 1286–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schùrks, M.; Kurth, T.; Geissler, I.; Tessmann, G.; Diener, H.-C.; Rosskopf, D. Cluster headache is associated with the G1246A polymorphism in the hypocretin receptor 2 gene. Neurology 2006, 66, 1917–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Healthy Subjects (n = 24) | PKD Patients (n = 64) | p-Value |

| Age | 46.83 ± 9.46 | 43.58 ± 13.19 | n.s |

| Sex | 12 F/12 M | 36 F/28 M | n.s |

| BMI | 24.82 ± 2.75 | 24 ± 6.3 | 0.863 |

| Orexin-A (pg/mL) | 321.49 ± 78.01 | 477.07 ± 70.51 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 122.76 ± 7.73 | 134.45 ± 15.14 | 0.009 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) | 82.92 ± 3.14 | 82.18 ± 7.4 | 0.732 |

| Ca tot (mg/dL) | 9.5 ± 0.41 | 9.65 ±0.56 | 0.283 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.62 ± 0.35 | 3.41 ± 4.48 | 0.107 |

| Tot cholesterol (mg/dL) | 205.86 ± 39.73 | 188.80 ± 35.14 | 0.063 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 122.17 ± 66.44 | 106.96 ± 54.61 | 0.286 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 128.65 ± 29.88 | 116.67 ± 37.44 | 0.147 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 54 ± 15.75 | 53.24 ± 19.01 | 0.859 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 85.17 ± 13.02 | 80.29 ± 14.01 | 0.220 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.61 ± 0.45 | 4.54 ± 0.28 | 0.355 |

| Creatinuria (mg/dL) | - | 63.44 ± 30.3 | - |

| Proteinuria (mg/dL) | - | 39.78 ± 87.8 | - |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 mq) | - | 67.8 ± 34.53 | - |

| Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)—Stage | (%) | ||

| G1 | - | 32.5 | - |

| G2 | - | 21.6 | - |

| G3a | - | 17.6 | - |

| G3b | - | 17.6 | - |

| G4 | - | 8.6 | - |

| G5 | - | 2.1 | - |

| Patient Code | HCRT SNPs | Orexin-A (pg/mL) | eGFR (mL/min/1.73 mq) | Systolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) | Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm/Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPR 2023/22 | rs9902709 | 456.29 | 58 | 130 | 80 |

| ADPKDRR | rs9902709 | 440.59 | 15 | 150 | 90 |

| MPR 2021/42 | rs9902709 | 477.47 | 110 | 140 | 80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nigro, E.; D’Arco, D.; Moscatelli, F.; Pisani, A.; Amicone, M.; Riccio, E.; Capuano, I.; Argentino, F.; Monda, M.; Messina, G.; et al. Increased Expression of Orexin-A in Patients Affected by Polycystic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116243

Nigro E, D’Arco D, Moscatelli F, Pisani A, Amicone M, Riccio E, Capuano I, Argentino F, Monda M, Messina G, et al. Increased Expression of Orexin-A in Patients Affected by Polycystic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):6243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116243

Chicago/Turabian StyleNigro, Ersilia, Daniela D’Arco, Fiorenzo Moscatelli, Antonio Pisani, Maria Amicone, Eleonora Riccio, Ivana Capuano, Francesca Argentino, Marcellino Monda, Giovanni Messina, and et al. 2024. "Increased Expression of Orexin-A in Patients Affected by Polycystic Kidney Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 6243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116243

APA StyleNigro, E., D’Arco, D., Moscatelli, F., Pisani, A., Amicone, M., Riccio, E., Capuano, I., Argentino, F., Monda, M., Messina, G., Daniele, A., & Polito, R. (2024). Increased Expression of Orexin-A in Patients Affected by Polycystic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 6243. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116243