Medication Exposure and Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Categories of Drugs Linked to Increased Risks of Dementia and AD

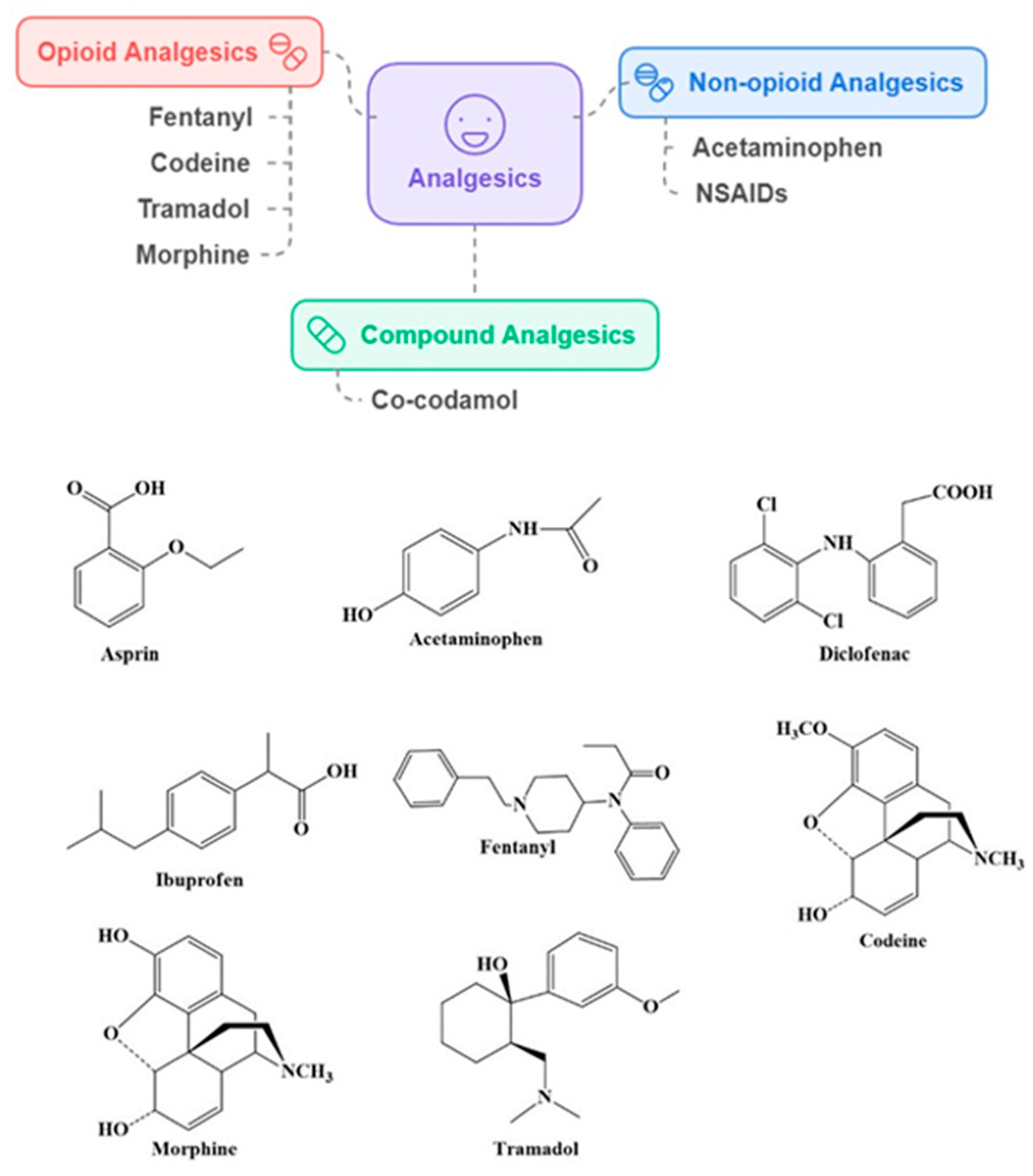

2.1. Analgesics

Association of Analgesics with Dementia and AD Risk

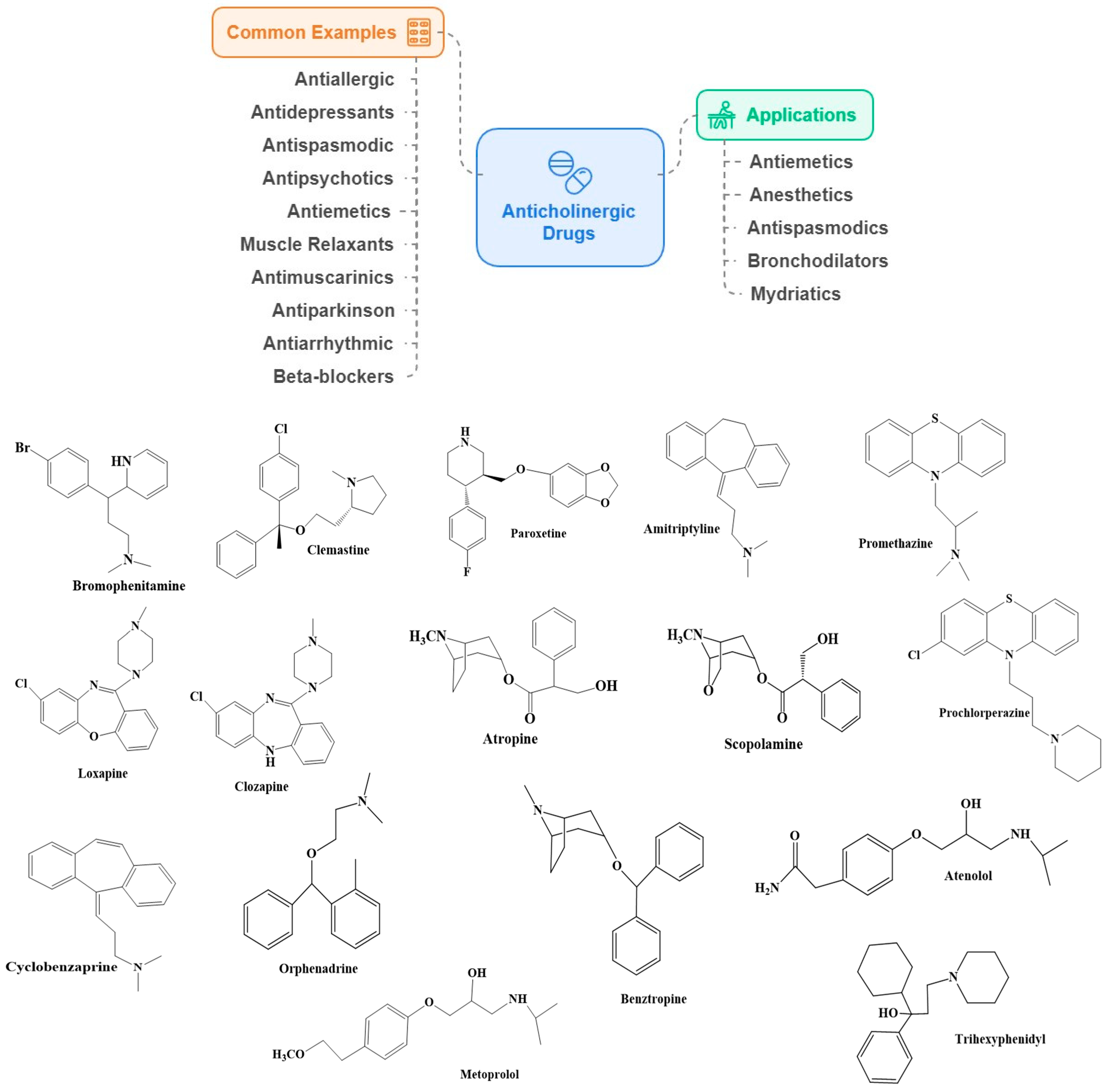

2.2. Anticholinergic Drugs

Association of Anticholinergics with Dementia and AD Risk

2.3. Benzodiazepine Drugs

Association of BZDs with Dementia and AD Risk

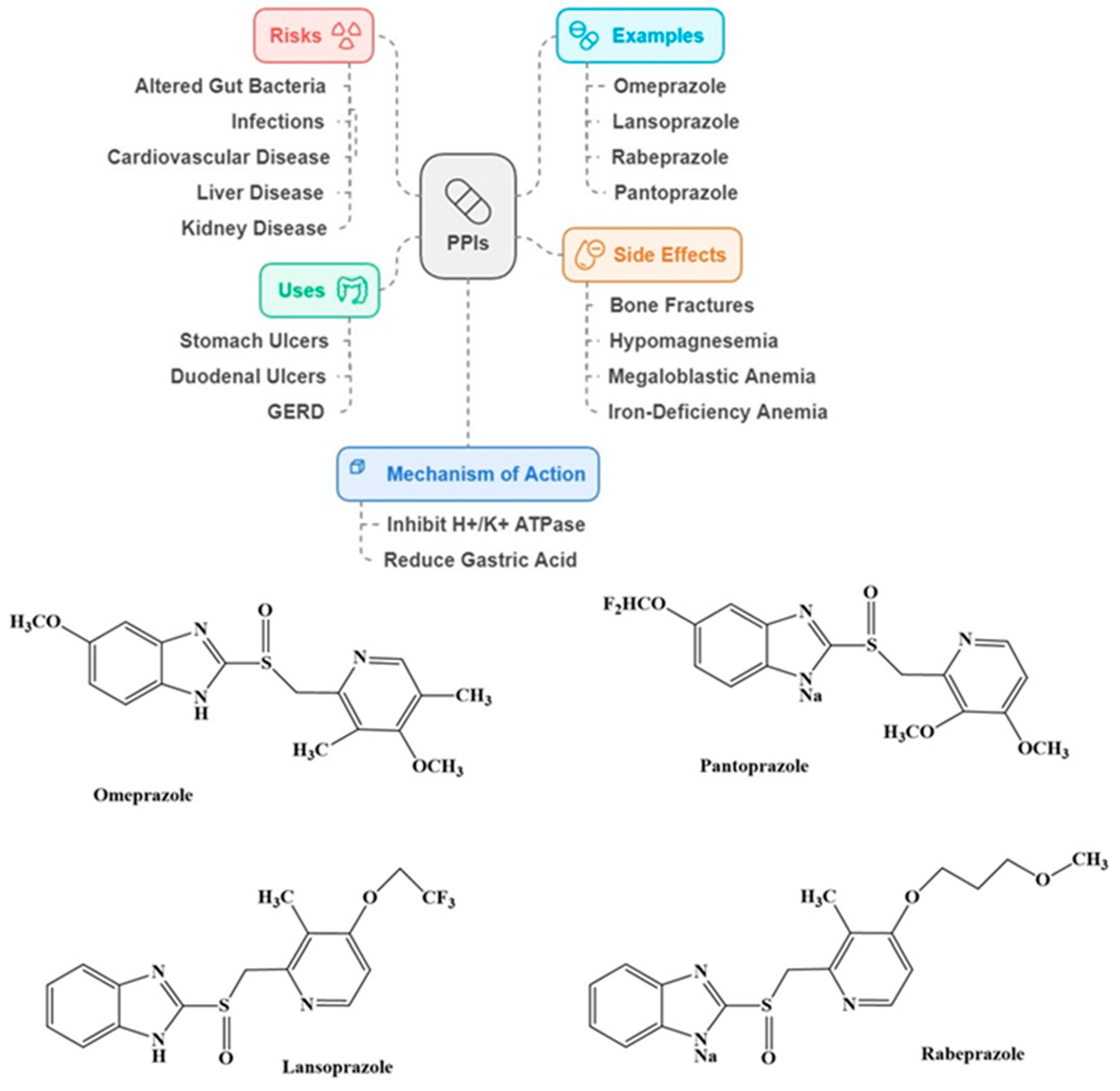

2.4. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

Association of PPIs with Dementia and AD Risk

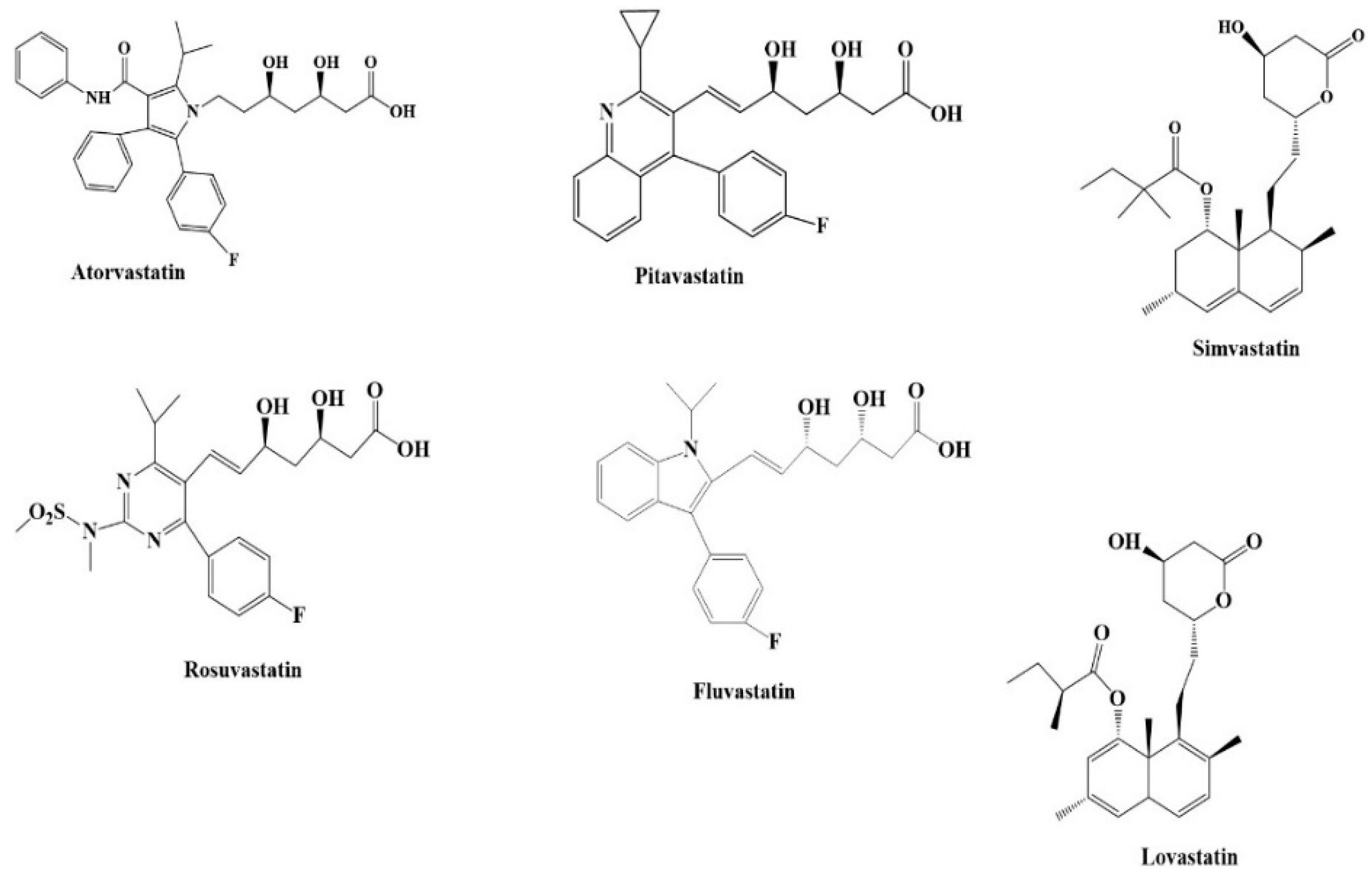

2.5. Statins

Association of Statins with Dementia and AD Risk

3. Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dementia, A.s.a. 2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures Report: Executive Summary Alzheimer’s Association: Chicago, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures?utm_source=google&utm_medium=paidsearch&utm_campaign=google_grants&utm_content=alzheimers&gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAo5u6BhDJARIsAAVoDWvZr_lVukNLQ2UWXS-xPBYpa67lV99gFNLybrdHl9FcWJ6iOD4iG78aAkQKEALw_wcB (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Anderson, P. Alzheimer’s Prevalence Predicted to Double by 2050. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/alzheimers-prevalence-predicted-double-2050-2024a10005o1?form=fpf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- WHO. Dementia; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One Behind in an Ageing World. 2023. Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/world-social-report-2023-leaving-no-one-behind-ageing-world (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Park, H.Y.; Park, J.W.; Song, H.J.; Sohn, H.S.; Kwon, J.W. The Association between Polypharmacy and Dementia: A Nested Case-Control Study Based on a 12-Year Longitudinal Cohort Database in South Korea. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, C.M.; Richardson, K.; Fox, C.; Maidment, I.; Steel, N.; Loke, Y.K.; Arthur, A.; Myint, P.K.; Campbell, N.; Boustani, M. Anticholinergic and benzodiazepine medication use and risk of incident dementia: A UK cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, A. Anticholinergic medications might increase the risk of AD. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, G.; Ferido, P.; Thunell, J.; Tysinger, B.; Zissimopoulos, J. Benzodiazepine use and the risk of dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2022, 8, e12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahzadeh, M.; Borhani Haghighi, A.; Namazi, M. Proton pump inhibitors: Predisposers to Alzheimer disease? J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2010, 35, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.L.; Gao, J.; Feng, S.Y. Proton pump inhibitor use does not increase dementia and Alzheimer’s disease risk: An updated meta-analysis of published studies involving 642305 patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marttinen, M.K.; Kautiainen, H.; Haanpää, M.; Pohjankoski, H.; Hintikka, J.; Kauppi, M.J. Analgesic purchases among older adults—A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenk, S.M.; Gu, Q.; Bohm, M.K. Prevalence of Prescription Opioid Analgesic Use Among Adults: National Center for Health Statistics, United States, 2013–2016. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/prescription-opioid/prescription-opioid.htm (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Pisarska, A. Przyjmowanie leków przeciwbólowych przez podopiecznych młodzieżowych ośrodków socjoterapii i młodzieżowych ośrodków wychowawczych. Paediatr. Fam. Med. Pediatr. I Med. Rodz. 2023, 19, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Luo, J. The survey on adolescents’ cognition, attitude, and behavior of using analgesics: Take Sichuan and Chongqing as an example. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 744685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norling, A.M.; Bennett, A.; Crowe, M.; Long, D.L.; Nolin, S.A.; Myers, T.; Del Bene, V.A.; Lazar, R.M.; Gerstenecker, A. Longitudinal associations of anticholinergic medications on cognition and possible mitigating role of physical activity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 1937–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebron Lipovec, N.; Jazbar, J.; Kos, M. Anticholinergic burden in children, adults and older adults in Slovenia: A Nationwide database study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukačišinová, A.; Reissigová, J.; Ortner-Hadžiabdić, M.; Brkic, J.; Okuyan, B.; Volmer, D.; Tadić, I.; Modamio, P.; Mariño, E.L.; Tachkov, K.; et al. Prevalence, country-specific prescribing patterns and determinants of benzodiazepine use in community-residing older adults in 7 European countries. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Jiménez-Trujillo, I.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Lima Florencio, L.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Patterns of non-medical use of benzodiazepines and Z-Drugs among adolescents and young adults: Gender differences and related factors. J. Subst. Use 2021, 26, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanika, L.G.T.; Reynolds, A.; Pattison, S.; Braund, R. Proton pump inhibitor use: Systematic review of global trends and practices. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, R.; Yao, H.; Yan, Q.; Xue, Y.; Sun, W.; Lu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, R.; Cui, B.; Feng, B. Trends and gaps in statin use for cardiovascular disease prevention in type 2 diabetes: A real-world study in Shanghai, China. Endocr. Pract. 2023, 29, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Mehta, L. Statin therapy in older adults for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: The balancing act. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Paul, A.M.; Gillespie, C.; Wall, H.K.; Loustalot, F.; Sperling, L.; Hong, Y. Recommended and observed statin use among US adults–National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2018. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakova, I.; Subileau, E.A.; Toegel, S.; Gruber, D.; Lachmann, B.; Urban, E.; Chesne, C.; Noe, C.R.; Neuhaus, W. Transport rankings of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs across blood-brain barrier in vitro models. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghossein, N.; Kang, M.; Lakhkar, A.D. Anticholinergic Medications; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Golovenko, N.Y.; Larionov, V. Pharmacodynamical and neuroreceptor analysis of the permeability of the blood-brain barrier for derivatives of 1,4-benzodiazepine. Neurophysiology 2014, 46, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Guerrero, G.; Amador-Muñoz, D.; Calderón-Ospina, C.A.; López-Fuentes, D.; Nava Mesa, M.O. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Dementia: Physiopathological Mechanisms and Clinical Consequences. Neural Plast. 2018, 2018, 5257285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodero, A.O.; Barrantes, F.J. Pleiotropic effects of statins on brain cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FMI. Analgesics Market Outlook for 2024 to 2034. 2024. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/analgesics-market (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Li, H.X.; Li, B.L.; Wang, T.H.; Zheng, H.; Yan, T. Double-edged sword of opioids in the treatment of cancer pain: Hyperalgesia. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 102, 3073–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borjkhani, M.; Bahrami, F.; Janahmadi, M. Assessing the Effects of Opioids on Pathological Memory by a Computational Model. Basic. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, C.W.; Ingram, S.L.; Connor, M.A.; Christie, M.J. How opioids inhibit GABA-mediated neurotransmission. Nature 1997, 390, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freye, E.; Levy, J.V. Mechanism of Action of Opioids and Clinical Effects. Opioids Med. 2008, 85–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisch, A.J.; Barrot, M.; Schad, C.A.; Self, D.W.; Nestler, E.J. Opiates inhibit neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7579–7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Ling, Y.; Huang, X.; Tan, S.; Li, W.; Xu, A.; Lyu, J. Associations between the use of common nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, genetic susceptibility and dementia in participants with chronic pain: A prospective study based on 194,758 participants from the UK Biobank. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 169, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Z.; He, P.; Liu, M.; Wu, Q.; Qin, X. Association of regular use of ibuprofen and paracetamol, genetic susceptibility, and new-onset dementia in the older population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2023, 84, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobbé-Duval, A.; Bézard, M.; Moutereau, S.; Kharoubi, M.; Oghina, S.; Zaroui, A.; Galat, A.; Chalard, C.; Hugon-Vallet, E.; Lemonnier, F. Prevalence and determinants of iron deficiency in cardiac amyloidosis. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 1314–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Yan, M.; Fu, Z.; Song, Y.; Lu, W.; Fu, A.d.; Yin, P. Association between anemia and cognitive decline among Chinese middle-aged and elderly: Evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.-x.; Qiu, L.-L.; Sun, J. Research progress on the role of inflammatory mechanisms in the development of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 3883204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Ghffar, E.A.; El-Nashar, H.A.; Eldahshan, O.A.; Singab, A.N.B. GC-MS analysis and hepatoprotective activity of the n-hexane extract of Acrocarpus fraxinifolius leaves against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in male albino rats. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, T.K.; Song, I.-A. Impact of prescribed opioid use on development of dementia among patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, S.Z.; Rotstein, A.; Goldberg, Y.; Reichenberg, A.; Kodesh, A. Opioid exposure and the risk of dementia: A national cohort study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 31, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAIC. New Use of Opioids Increases Risk of Death Elevenfold in Older Adults with Dementia. 2024 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference|28 July–1 August 2024|Philadelphia, USA. Available online: https://aaic.alz.org/releases_2023/opioids-increase-risk-death-older-adults-dementia.asp (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Gao, Y.; Su, B.; Ding, L.; Qureshi, D.; Hong, S.; Wei, J.; Zeng, C.; Lei, G.; Xie, J. Association of Regular Opioid Use with Incident Dementia and Neuroimaging Markers of Brain Health in Chronic Pain Patients: Analysis of UK Biobank. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2024, 32, 1154–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitner, J.C.; Haneuse, S.; Walker, R.; Dublin, S.; Crane, P.; Gray, S.; Larson, E. Risk of dementia and AD with prior exposure to NSAIDs in an elderly community-based cohort. Neurology 2009, 72, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnen, J.A.; Larson, E.B.; Walker, R.; Haneuse, S.; Crane, P.K.; Gray, S.L.; Breitner, J.C.; Montine, T.J. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with increased neuritic plaques. Neurology 2010, 75, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dublin, S.; Walker, R.L.; Gray, S.L.; Hubbard, R.A.; Anderson, M.L.; Yu, O.; Montine, T.J.; Crane, P.K.; Sonnen, J.A.; Larson, E.B. Use of Analgesics (Opioids and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) and Dementia-Related Neuropathology in a Community-Based Autopsy Cohort. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 58, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, M.E.; Larson, E.B.; Walker, R.L.; Keene, C.D.; Postupna, N.; Cholerton, B.; Sonnen, J.A.; Dublin, S.; Crane, P.K.; Montine, T.J. Associations between Use of Specific Analgesics and Concentrations of Amyloid-β 42 or Phospho-Tau in Regions of Human Cerebral Cortex. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 61, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, L.; Ongini, E.; Wenk, G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in Alzheimer’s disease: Old and new mechanisms of action. J. Neurochem. 2004, 91, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeer, P.L.; Schulzer, M.; McGeer, E.G. Arthritis and anti-inflammatory agents as possible protective factors for Alzheimer’s disease: A review of 17 epidemiologic studies. Neurology 1996, 47, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, W.F.; Kawas, C.; Corrada, M.; Metter, E.J. Risk of Alzheimer’s disease and duration of NSAID use. Neurology 1997, 48, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.; Kirby, L.; Hempelman, S.; Berry, D.; McGeer, P.; Kaszniak, A.; Zalinski, J.; Cofield, M.; Mansukhani, L.; Willson, P. Clinical trial of indomethacin in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1993, 43, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etminan, M.; Gill, S.; Samii, A. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 2003, 327, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, A.C.; Milton, F.A.; Cvoro, A.; Sieglaff, D.H.; Campos, J.C.; Bernardes, A.; Filgueira, C.S.; Lindemann, J.L.; Deng, T.; Neves, F.A.; et al. Mechanisms of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ regulation by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Nucl. Recept. Signal 2015, 13, e004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Alam, Q.; Haque, A.; Ashafaq, M.; Khan, M.J.; Ashraf, G.M.; Ahmad, M. Current progress on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist as an emerging therapeutic approach for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: An update. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dublin, S.; Walker, R.L.; Gray, S.L.; Hubbard, R.A.; Anderson, M.L.; Yu, O.; Crane, P.K.; Larson, E.B. Prescription Opioids and Risk of Dementia or Cognitive Decline: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, H.; Hamina, A.; Lampela, P.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Karttunen, N.; Tolppanen, A.-M.; Hartikainen, S. Is Alzheimer’s Disease Associated with Previous Opioid Use? Pain. Med. 2017, 19, 2115–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F. NSAID Exposure and Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis From Cohort Studies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veld, B.A.i.t.; Ruitenberg, A.; Hofman, A.; Launer, L.J.; Duijn, C.M.v.; Stijnen, T.; Breteler, M.M.B.; Stricker, B.H.C. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1515–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.H.; Kang, M.J.; Sharma, N.; An, S.S.A. Beauty of the beast: Anticholinergic tropane alkaloids in therapeutics. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect 2022, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, C.M.; Richardson, K.; Savva, G.M.; Fox, C.; Arthur, A.; Loke, Y.K.; Steel, N.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Robinson, L. Increasing prevalence of anticholinergic medication use in older people in England over 20 years: Cognitive function and ageing study I and II. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, C.; Richardson, K.; Maidment, I.D.; Savva, G.M.; Matthews, F.E.; Smithard, D.; Coulton, S.; Katona, C.; Boustani, M.A.; Brayne, C. Anticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: The medical research council cognitive function and ageing study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerretsen, P.; Pollock, B.G. Drugs with anticholinergic properties: A current perspective on use and safety. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2011, 10, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.L.; Anderson, M.L.; Dublin, S.; Hanlon, J.T.; Hubbard, R.; Walker, R.; Yu, O.; Crane, P.K.; Larson, E.B. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: A prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancelin, M.L.; Artero, S.; Portet, F.; Dupuy, A.-M.; Touchon, J.; Ritchie, K. Non-degenerative mild cognitive impairment in elderly people and use of anticholinergic drugs: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2006, 332, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrière, I.; Fourrier-Reglat, A.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Rouaud, O.; Pasquier, F.; Ritchie, K.; Ancelin, M.-L. Drugs with anticholinergic properties, cognitive decline, and dementia in an elderly general population: The 3-city study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Daerr, M.; Bickel, H.; Pentzek, M.; Riedel-Heller, S.; Wagner, M.; Weyerer, S.; Wiese, B.; van den Bussche, H. Anticholinergic drug use and risk for dementia: Target for dementia prevention. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 260, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Fox, C.; Maidment, I.; Steel, N.; Loke, Y.K.; Arthur, A.; Myint, P.K.; Grossi, C.M.; Mattishent, K.; Bennett, K.; et al. Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: Case-control study. BMJ 2018, 361, k1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, K.-i.; Kim, S.; Cho, Y.H.; Cho, S.-i. Association of Anticholinergic Use with Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease: Population-based Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Anticholinergic drug exposure and the risk of dementia: There is modest evidence for an association but not for causality. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coupland, C.A.; Hill, T.; Dening, T.; Morriss, R.; Moore, M.; Hippisley-Cox, J. Anticholinergic drug exposure and the risk of dementia: A nested case-control study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.B.; Shi, L.; Zhu, X.M.; Bao, Y.P.; Bai, L.J.; Li, J.Q.; Liu, J.J.; Han, Y.; Shi, J.; Lu, L. Anticholinergic drugs and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancelli, I.; Gigli, G.L.; Piani, A.; Zanchettin, B.; Janes, F.; Rinaldi, A.; Valente, M. Drugs with anticholinergic properties as a risk factor for cognitive impairment in elderly people: A population-based study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 28, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigand, A.J.; Bondi, M.W.; Thomas, K.R.; Campbell, N.L.; Galasko, D.R.; Salmon, D.P.; Sewell, D.; Brewer, J.B.; Feldman, H.H.; Delano-Wood, L. Association of anticholinergic medications and AD biomarkers with incidence of MCI among cognitively normal older adults. Neurology 2020, 95, e2295–e2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Rowan, M.; Edwards, S.; Noel-Storr, A.H.; McCleery, J.; Myint, P.K.; Soiza, R.; Stewart, C.; Loke, Y.K.; Quinn, T.J. Anticholinergic burden (prognostic factor) for prediction of dementia or cognitive decline in older adults with no known cognitive syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 5, Cd013540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, L.; Gray, S.L.; Boudreau, D.M.; Thummel, K.; Edwards, K.L.; Fullerton, S.M.; Crane, P.K.; Larson, E.B. Cumulative Antidepressant Use and Risk of Dementia in a Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 1948–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Huang, C.C.; Ho, C.H.; Huang, Y.T.; Wu, M.P.; Ou, M.J.; Yang, C.H.; Chen, P.J. Cumulative use of therapeutic bladder anticholinergics and the risk of dementia in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: A nationwide 12-year cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur, J.; Russ, T.C.; Cox, S.R.; Marioni, R.E.; Muniz-Terrera, G. Association between anticholinergic burden and dementia in UK Biobank. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2022, 8, e12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonawalla, I.B.; Xu, Y.; Gaddy, R.; James, A.; Ruble, M.; Burns, S.; Dixon, S.W.; Suehs, B.T. Anticholinergic exposure and its association with dementia/Alzheimer’s disease and mortality in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heser, K.; Luck, T.; Röhr, S.; Wiese, B.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Oey, A.; Bickel, H.; Mösch, E.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J. Potentially inappropriate medication: Association between the use of antidepressant drugs and the subsequent risk for dementia. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiyama, Y.; Kojima, A.; Itoh, K.; Uchiyama, T.; Arai, K. Anticholinergics boost the pathological process of neurodegeneration with increased inflammation in a tauopathy mouse model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 45, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-P.; Chien, W.-C.; Chung, C.-H.; Chang, H.-A.; Kao, Y.-C.; Tzeng, N.-S. Are anticholinergic medications associated with increased risk of dementia and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia? A nationwide 15-year follow-up cohort study in Taiwan. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, L.F.; Anstey, K.J.; Sachdev, P. Use of medications with anticholinergic properties and cognitive function in a young-old community sample. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, H.; Ricci, F.; Di Martino, G.; Bachus, E.; Nilsson, E.D.; Ballerini, P.; Melander, O.; Hansson, O.; Nägga, K.; Magnusson, M.; et al. Beta-blocker therapy and risk of vascular dementia: A population-based prospective study. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 125–126, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroevers, J.L.; Hoevenaar-Blom, M.P.; Busschers, W.B.; Hollander, M.; Van Gool, W.A.; Richard, E.; Van Dalen, J.W.; Moll van Charante, E.P. Antihypertensive medication classes and risk of incident dementia in primary care patients: A longitudinal cohort study in the Netherlands. Lancet Reg. Health—Eur. 2024, 42, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaman, E.E.; Bonde, A.N.; Larsen, S.M.U.; Ozenne, B.; Lohela, T.J.; Nedergaard, M.; Gíslason, G.H.; Knudsen, G.M.; Holst, S.C. Blood–brain barrier permeable β-blockers linked to lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease in hypertension. Brain 2022, 146, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Chen, X.; Wu, T.; Li, L.; Fei, X. Risk of dementia in long-term benzodiazepine users: Evidence from a meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 15, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shash, D.; Kurth, T.; Bertrand, M.; Dufouil, C.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Berr, C.; Ritchie, K.; Dartigues, J.F.; Bégaud, B.; Alpérovitch, A. Benzodiazepine, psychotropic medication, and dementia: A population-based cohort study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 12, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, E.; Comijs, H.; Gundy, C.; Sonnenberg, C.; Jonker, C.; Beekman, A. The effect of chronic benzodiazepine use on cognitive functioning in older persons: Good, bad or indifferent? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry J. Psychiatry Late Life Allied Sci. 2007, 22, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapiainen, V.; Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Hartikainen, S.; Tolppanen, A.M. The risk of Alzheimer’s disease associated with benzodiazepines and related drugs: A nested case–control study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 138, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Jung, S.J.; Choi, J.-w.; Shin, A.; Lee, Y.J. Use of sedative-hypnotics and the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gage, S.B.; Moride, Y.; Ducruet, T.; Kurth, T.; Verdoux, H.; Tournier, M.; Pariente, A.; Bégaud, B. Benzodiazepine use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: Case-control study. BMJ 2014, 349, g5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M.; Iqbal, U.; Walther, B.; Atique, S.; Dubey, N.K.; Nguyen, P.-A.; Poly, T.N.; Masud, J.H.B.; Li, Y.-C.; Shabbir, S.-A. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia in the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 2017, 47, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarelainen, L.; Tolppanen, A.M.; Koponen, M.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Hartikainen, S.; Taipale, H. Risk of death associated with new benzodiazepine use among persons with Alzheimer disease: A matched cohort study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomm, W.; von Holt, K.; Thomé, F.; Broich, K.; Maier, W.; Weckbecker, K.; Fink, A.; Doblhammer, G.; Haenisch, B. Regular benzodiazepine and Z-substance use and risk of dementia: An analysis of German claims data. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016, 54, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetta, R.C.; da Mata, B.P.M.; Mastroianni, P.d.C. Association between development of dementia and use of benzodiazepines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2018, 38, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninkilampi, R.; Eslick, G.D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of dementia associated with benzodiazepine use, after controlling for protopathic bias. CNS Drugs 2018, 32, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettcheto, M.; Olloquequi, J.; Sánchez-López, E.; Busquets, O.; Cano, A.; Manzine, P.R.; Beas-Zarate, C.; Castro-Torres, R.D.; García, M.L.; Bulló, M.; et al. Benzodiazepines and Related Drugs as a Risk Factor in Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Association between benzodiazepine use and dementia: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, T.; Proust-Lima, C.; Akbaraly, T.; Amieva, H.; Tzourio, C.; Chevassus, H.; Picot, M.-C.; Jacqumin-Gadda, H.; Berr, C. Chronic use of benzodiazepines and latent cognitive decline in the elderly: Results from the Three-city study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Lim, Y.Y.; Neumeister, A.; Ames, D.; Ellis, K.A.; Harrington, K.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Restrepo, C.; Martins, R.N.; Masters, C.L. Amyloid-β, anxiety, and cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease: A multicenter, prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, S.L.; Hu, T.; Spadola, C.E.; Li, T.; Naseh, M.; Burgess, A.; Cadet, T. Mild cognitive impairment: Associations with sleep disturbance, apolipoprotein e4, and sleep medications. Sleep Med. 2018, 52, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biétry, F.A.; Pfeil, A.M.; Reich, O.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Meier, C.R. Benzodiazepine use and risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease: A case-control study based on Swiss claims data. CNS Drugs 2017, 31, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imfeld, P.; Bodmer, M.; Jick, S.S.; Meier, C.R. Benzodiazepine use and risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia: A case–control analysis. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaz, P.; Garjón, J.; Beitia, G.; Beltrán, I.; Librero, J.; Ibáñez, B.; Arroyo, P.; Ariz, M.J. Association between benzodiazepine use and development of dementia. Med. Clin. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 156, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.C.; Liao, M.H.; Su, C.H.; Poly, T.N.; Lin, M.C. Benzodiazepine Use and the Risk of Dementia in the Elderly Population: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, L.B.; Myra Kim, H.; Ignacio, R.V.; Strominger, J.; Maust, D.T. Use of benzodiazepines and risk of incident dementia: A retrospective cohort study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2022, 77, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.X.; Malkani, R.G. Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and stress intersect in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 10, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Flores Guzmán, B.; Vinnakota, C.; Govindpani, K.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.; Kwakowsky, A. The GABAergic system as a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2018, 146, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastbom, J.; Forsell, Y.; Winblad, B. Benzodiazepines may have protective effects against Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 1998, 12, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellana, C.; Pecere, S.; Furnari, M.; Telese, A.; Matteo, M.V.; Haidry, R.; Eusebi, L.H. Side effects of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: Practical considerations. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2021, 131, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Fan, Q.; Xiao, S.; Chen, K. Changes in proton pump inhibitor prescribing trend over the past decade and pharmacists’ effect on prescribing practice at a tertiary hospital. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yibirin, M.; De Oliveira, D.; Valera, R.; Plitt, A.E.; Lutgen, S. Adverse Effects Associated with Proton Pump Inhibitor Use. Cureus 2021, 13, e12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Ho, Y.-F.; Hung, L.; Chen, C.; Tsai, T. Determination and pharmacokinetic profile of omeprazole in rat blood, brain and bile by microdialysis and high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 949, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, A.; Nordberg, A.; Långström, B.; Darreh-Shori, T. Proton pump inhibitors act with unprecedented potencies as inhibitors of the acetylcholine biosynthesizing enzyme—A plausible missing link for their association with incidence of dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, R.; Gilmartin, J.F.M.; Kemp, W.; Hopper, I.; Liew, D. Dementia, cognitive impairment and proton pump inhibitor therapy: A systematic review. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 1426–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Luo, Z.; Yu, S.; Tang, Z. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e14422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomm, W.; von Holt, K.; Thomé, F.; Broich, K.; Maier, W.; Fink, A.; Doblhammer, G.; Haenisch, B. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: A pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016, 73, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welu, J.; Metzger, J.; Bebensee, S.; Ahrendt, A.; Vasek, M. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of dementia in the veteran population. Fed. Pract. 2019, 36, S27. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-Y.; Lin, H.-J.; Wu, W.-T.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-L.; Kao, J.; You, S.-L.; Chou, Y.-C.; Sun, C.-A. Clinical Use of Acid Suppressants and Risk of Dementia in the Elderly: A Pharmaco-Epidemiological Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenisch, B.; von Holt, K.; Wiese, B.; Prokein, J.; Lange, C.; Ernst, A.; Brettschneider, C.; König, H.-H.; Werle, J.; Weyerer, S. Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 265, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wilde, M.C.; Vellas, B.; Girault, E.; Yavuz, A.C.; Sijben, J.W. Lower brain and blood nutrient status in Alzheimer’s disease: Results from meta-analyses. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2017, 3, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, S.-Y.; Chien, C.-Y.; Wu, D.-C.; Lin, K.-D.; Ho, B.-L.; Chang, Y.-H.; Chang, Y.-P. Risk of dementia from proton pump inhibitor use in Asian population: A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, E. Vitamin B12, folic acid, and the nervous system. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Cruz, D.; Asamoah, N.; Buxbaum, A.; Sohar, I.; Lobel, P.; Maxfield, F.R. Activation of microglia acidifies lysosomes and leads to degradation of Alzheimer amyloid fibrils. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nighot, M.; Nighot, P.; Ma, T. Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPI) induces colonic Tight Junction barrier (TJ) dysfunction via an upregulation of TJ pore forming Caludin-2 protein. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongon, N.; Chamniansawat, S. Hippocampal synaptic dysfunction and spatial memory impairment in omeprazole-treated rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 2871–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, H.; Tolppanen, A.-M.; Tiihonen, M.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Hartikainen, S. No association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2017, 112, 1802–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, F.C.; Steenland, K.; Zhao, L.; Wharton, W.; Levey, A.I.; Hajjar, I. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1969–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksey, R.; Kennedy, J.; Dennis, M.S.; Escott-Price, V.; Lyons, R.A.; Seaborne, M.; Brophy, S. Proton pump inhibitors and dementia risk: Evidence from a cohort study using linked routinely collected national health data in Wales, UK. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, N.; Nolde, M.; Krause, E.; Güntner, F.; Günter, A.; Tauscher, M.; Gerlach, R.; Meisinger, C.; Linseisen, J.; Baumeister, S.E. Do proton pump inhibitors increase the risk of dementia? A systematic review, meta-analysis and bias analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, S.L.; Walker, R.L.; Dublin, S.; Yu, O.; Aiello Bowles, E.J.; Anderson, M.L.; Crane, P.K.; Larson, E.B. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Dementia Risk: Prospective Population-Based Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Bondia, F.; Dakterzada, F.; Galván, L.; Buti, M.; Besanson, G.; Gill, E.; Buil, R.; de Batlle, J.; Piñol-Ripoll, G. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and non-Alzheimer’s dementias. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, L.; Yan, X. No association between acid suppressant use and risk of dementia: An updated meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 78, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayyedi, P.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Bosch, J.; Connolly, S.J.; Dyal, L.; Shestakovska, O.; Leong, D.; Anand, S.S.; Störk, S.; Branch, K.R. Safety of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, multi-year, randomized trial of patients receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 682–691.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, C.; Veloso, M.; Borda, S. Proton pump inhibitors and dementia: What association? Dement. Neuropsychol. 2023, 17, e20220048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, L.R.; Mitton, M.W.; Arvik, B.M.; Doraiswamy, P.M. Statin-associated memory loss: Analysis of 60 case reports and review of the literature. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2003, 23, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizar, O.; Khare, S.; Patel, P.; Talati, R. Statin medications. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Important Safety Label Changes to Cholesterol-Lowering Statin Drugs; US Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S.F.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Negative statin-related news stories decrease statin persistence and increase myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality: A nationwide prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Higdon, R.; Kukull, W.A.; Peskind, E.; Van Valen Moore, K.; Tsuang, D.; van Belle, G.; McCormick, W.; Bowen, J.D.; Teri, L.; et al. Statin therapy and risk of dementia in the elderly: A community-based prospective cohort study. Neurology 2004, 63, 1624–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, P.P.; Sparks, D.L.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Tschanz, J.; Norton, M.; Steinberg, M.; Welsh-Bohmer, K.A.; Breitner, J.C. Do statins reduce risk of incident dementia and Alzheimer disease? The Cache County Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Ryan, J.; Ernst, M.E.; Zoungas, S.; Tonkin, A.M.; Woods, R.L.; McNeil, J.J.; Reid, C.M.; Curtis, A.J.; Wolfe, R.; et al. Effect of Statin Therapy on Cognitive Decline and Incident Dementia in Older Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 3145–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, E.C.; Ebner, M.K.; Ramanan, S.; Godek, T.A.; Pugh, E.A.; Bartlett, H.H.; McDonald, J.W.; Mecca, M.C.; van Dyck, C.H.; Mecca, A.P. Statin Use and Risk of Cognitive Decline in the ADNI Cohort. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, B.R.; Daiello, L.A.; Dahabreh, I.J.; Springate, B.A.; Bixby, K.; Murali, M.; Trikalinos, T.A. Do statins impair cognition? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, H.; Ghasemi, F.; Barreto, G.E.; Sathyapalan, T.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. The effects of statins on microglial cells to protect against neurodegenerative disorders: A mechanistic review. Biofactors 2020, 46, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukiya, A.N.; Blank, P.S.; Rosenhouse-Dantsker, A. Cholesterol intake and statin use regulate neuronal G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channels. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.M.; Shin, D.W.; Yoo, T.G.; Cho, M.H.; Jang, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. Association between statin use and Alzheimer’s disease with dose response relationship. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poly, T.N.; Islam, M.M.; Walther, B.A.; Yang, H.C.; Wu, C.C.; Lin, M.C.; Li, Y.C. Association between Use of Statin and Risk of Dementia: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Neuroepidemiology 2020, 54, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Tripathy, S.; Chuzi, S.; Peterson, J.; Stone, N.J. Association between statin use and cognitive function: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials and observational studies. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2021, 15, 22–32.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C.; Haan, M.N.; Galea, S.; Langa, K.M.; Kalbfleisch, J.D. Use of statins and incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment without dementia in a cohort study. Neurology 2008, 71, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, M.D.; Hofman, A.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Stricker, B.H.; Breteler, M.M. Statins are associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer disease regardless of lipophilicity. The Rotterdam Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2009, 80, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.Y.; Chou, Y.C.; Chou, Y.J.; Yang, Y.F.; Huang, N. Statin use and incident dementia: A nationwide cohort study of Taiwan. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 173, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmastroni, E.; Molari, G.; De Beni, N.; Colpani, O.; Galimberti, F.; Gazzotti, M.; Zambon, A.; Catapano, A.L.; Casula, M. Statin use and risk of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 29, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.H.; Lin, C.L.; Huang, C.N. Neuroprotective effects of statins against amyloid β-induced neurotoxicity. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Oliva, A.; Zepeda, A.; Arias, C. The complex actions of statins in brain and their relevance for Alzheimer’s disease treatment: An analytical review. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2014, 11, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.-w.; Katherine Teng, T.-H.; Tse, Y.-K.; Wei Tsang, C.T.; Yu, S.-Y.; Wu, M.-Z.; Li, X.-l.; Hung, D.; Tse, H.-F.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. Statins and risks of dementia among patients with heart failure: A population-based retrospective cohort study in Hong Kong. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2024, 44, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos-Palacios, L.; Sanz-Cánovas, J.; Muñoz-Ubeda, M.; Lopez-Carmona, M.D.; Perez-Belmonte, L.M.; Lopez-Sampalo, A.; Gomez-Huelgas, R.; Bernal-Lopez, M.R. Statin therapy in very old patients: Lights and shadows. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 779044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, F.; Biffi, A.; Ronco, R.; Franchi, M.; Cammarota, S.; Citarella, A.; Conti, V.; Filippelli, A.; Sellitto, C.; Corrao, G. Cardiovascular outcomes and mortality associated with discontinuing statins in older patients receiving polypharmacy. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2113186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Byrne, S.; O’Connor, M.N.; Ryan, C.; Gallagher, P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing 2014, 44, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel, A.G.S.B.C.U.E.; Fick, D.M.; Semla, T.P.; Steinman, M.; Beizer, J.; Brandt, N.; Dombrowski, R.; DuBeau, C.E.; Pezzullo, L.; Epplin, J.J. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel; Campanelli, C.M. American Geriatrics Society Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Medication Type | Young Adults (%) | Elderly (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics | 20–60 | 70–85 | [11,12,13,14] |

| Anticholinergics | 20–25 | 30–50 | [15,16] |

| Benzodiazepines | 5–10 | 30–40 | [17,18] |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 2–5 | 35–50 | [19] |

| Statins | 15–25 | 35–60 | [20,21,22] |

| Drug | Target | 1 Protein Expression and Location | 1 Tissue RNA Expression | 1 Cell-Type RNA Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics | Cox 1 and 2, opioid receptors (μκ Others (BACE1, PPARγ) | Cox1: Cytoplasmic expression at variable levels in several tissues, high expression in squamous epithelia, megakaryocytes, fallopian tube, brain, and subsets of cells in tissue stroma. Localized to the Golgi apparatus, Vesicles | Tissue-enhanced (Intestine, Skin, Urinary bladder). Skin—Cornification (mainly). Low human brain regional specificity. Macrophages and Microglia—Immune response (mainly) | Group-enriched (granulocytes, Glandular and luminal cells). Cell-type-enriched (Adrenal gland—Macrophages, Heart muscle—Fibroblasts, Skeletal muscle—Fibroblasts, Skin—Keratinocyte (other), Spleen—Platelets) |

| Cox 2: Cytoplasmic and membranous expression in selected tissues, including seminal vesicle, urinary bladder, and gall bladder. Localized to the Vesicles, Cytosol | Tissue-enhanced (Bone marrow, Seminal vesicle, Urinary bladder). Tissue-enhanced (Bone marrow, Seminal vesicle, Urinary bladder). Low human brain regional specificity. Neurons—Mixed function (mainly) | Group-enriched (Basal prostatic cells, granulocytes, Langerhans cells, monocytes, Macrophages, Alveolar cells type 1). Cell-type-enriched (Heart muscle—Fibroblasts) | ||

| Opioid receptor μ: Membranous expression in seminiferous tubules. Soma, dendrite, axon, and synapse in neurons. | Tissue-enhanced (Brain, Testis). Low human brain regional specificity. Sub-cortical—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enhanced (Excitatory neurons, Early spermatids, Late spermatids, Inhibitory neurons, Microglial cells). Cell-type-enriched (Adrenal gland—Adrenal medulla cells, Testis—Early spermatids, Testis—Late spermatids) | ||

| Opioid receptor κ: Cytoplasmic expression in CNS. Localized to the Plasma membrane, Nucleoplasm, Cytosol | Tissue-enhanced (Brain, Prostate, Skeletal muscle), Low human brain regional specificity, Neurons—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enhanced (Prostatic glandular cells, Inhibitory neurons, Extravillous trophoblasts, Glandular and luminal cells, Excitatory neurons, Leydig cells). Cell-type-enriched (Colon—Colon enteroendocrine cells, Minor Salivary Gland—Adipocytes (Minor salivary gland), Prostate—Prostate glandular cells) | ||

| BACE1: Granular cytoplasmic expression in several tissues. Localized to the Plasma membrane | Group-enriched (Brain, Pancreas). Low human brain regional specificity. White matter—Myelination (mainly) | Cell-type-enhanced (Late spermatids, Cone photoreceptor cells, Oligodendrocytes) | ||

| PPARγ: Cytoplasmic and nuclear expression in several tissues. Localized to the Nucleoplasm, Vesicles | Tissue-enhanced (Adipose tissue). Low human brain regional specificity. Neurons—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enhanced (Extravillous trophoblasts, Adipocytes, Distal enterocytes, Cytotrophoblasts, Syncytiotrophoblasts) | ||

| Anticholinergics | mAChR (M1–M5) | M1: Cytoplasmic expression in pyramidal neurons and Purkinje cells. Soma, dendrite, and synapse in neurons. | Group-enriched (Brain, Prostate, Salivary gland), Group-enriched (Amygdala, Basal ganglia, Cerebral cortex, Hippocampal formation, White matter), Neurons—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enriched (Prostatic glandular cells), Cell-type-enriched (Heart muscle—Cardiomyocytes, Liver—Hepatic stellate cells, Testis—Early spermatids, Testis—Late spermatids), Group-enriched (Brain, Prostate, Salivary gland) |

| M2: Ubiquitous cytoplasmic expression in all tissues at variable levels. Localized to the Plasma membrane, Nucleoli, Golgi apparatus, Primary cilium, Basal body | Tissue-enhanced (Heart muscle, Intestine), Heart muscle—Heart development (mainly), Low human brain regional specificity, Hindbrain—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enriched (Heart muscle—Cardiomyocytes, Liver—Hepatic stellate cells, Testis—Early spermatids, Testis—Late spermatids) Group-enriched (Inhibitory neurons, Cardiomyocytes, Excitatory neurons) | ||

| M3: General cytoplasmic expression at variable levels. Localized to the Plasma membrane | Tissue-enhanced (Salivary gland), Salivary gland—Salivary secretion (mainly) Low human brain regional specificity, Astrocytes—Astrocyte-neuron interactions (mainly) | Cell-type-enriched (Heart muscle—Smooth muscle cells, Minor Salivary Gland—Minor salivary glandular cells, Skin—Eccrine sweat gland cells, Thyroid gland—Endothelial cells), Group-enriched (Excitatory neurons, Inhibitory neurons) | ||

| M4: Cytoplasmic and membranous expression in several tissues, including the brain and intestines Localized to the Golgi apparatus and Nucleoplasm | Tissue-enhanced (Brain, Intestine, Lymphoid tissue), Human brain regional-enhanced (Basal ganglia), Neurons—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enriched (Colon—Colon enteroendocrine cells, Skin—Keratinocyte (granular), Testis—Early spermatids, Testis—Late spermatids) | ||

| M5: Tissue profile NA. Membrane, Intracellular (different isoforms) | Tissue-enriched (Brain), Low human brain regional specificity, Oligodendrocytes—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enriched (Oligodendrocytes, Testis—Early spermatids, Testis—Late spermatids) | ||

| Benzodiazepines | GABA-A receptor | Selective expression in neuropil and subset of neurons, Localized to the Plasma membrane, Nucleoplasm, Synapse in neurons | Group-enriched (Brain, Retina) Brain—Synaptic signal transduction (mainly) Low human brain regional specificity Neurons—Mixed function (mainly) | Cell-type-enriched (Adrenal gland—Adrenal medulla cells, Stomach—Gastric enteroendocrine cells, Testis—Early spermatids, Testis—Late spermatids) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | H/K-ATPase | Membranous expression in most tissues. Localized to the Vesicles, Plasma membrane | Tissue-enhanced (Parathyroid gland), Parathyroid gland—Vesicular transport (mainly). Low human brain regional specificity, Neurons and Synapses—Synaptic function (mainly) | Cell-type-enriched (Adrenal gland—Adrenal cortex cells, Lung—Alveolar cells type 2, Thyroid gland—Thyroid glandular cells) |

| Statins | HMG-CoA reductase | Ubiquitous cytoplasmic expression. Membrane, Intracellular (different isoforms) | Tissue-enhanced (Liver) Liver and Intestine—Lipid metabolism (mainly); Low human brain regional specificity. Neurons—Mixed function | Cell-type-enriched (Adrenal gland—Adrenal cortex cells, Lung—Alveolar cells type 2, Minor Salivary Gland—Minor salivary gland basal cells) |

| Study | Population Sample | Analgesic Type | AD/Dementia Risk Factor | Statistics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective Study—UK Biobank | n = 194,758 (aged ≥ 60) | Aspirin, Paracetamol, 2–3 NSAIDs | Frequent use of paracetamol, as opposed to ibuprofen, was linked to a notably increased likelihood of developing dementia in elderly | Aspirin HR: 1.12 (CI: 1.01–1.24, p < 0.05) Paracetamol HR: 1.15 (CI:1.05–1.27, p < 0.01) 2–3 NSAIDs HR: 1.2 (CI:1.08–1.33, p < 0.05) | [35] |

| Prospective national cohort study—Israel | n = 91,307 (aged ≥ 60) | Opioids | Linked with an increased dementia risk | aHR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.01–1.92, p < 0.05 in opioid exposed group aged 75+ yrs | [41] |

| Community-based cohort—West King County, US | n = 3392 (aged ≥ 65) | NSAIDs | Heavy NSAID users had increased incidence of dementia and AD | Dementia: aHR 1.66 95% CI: 1.24–2.24 AD: aHR:1.57 95% CI: 1.10–2.23 | [44] |

| Population Cohort Study- Korean patients | n = 1,261,682 | Opioids | Increased AD and dementia risk | Dementia: 15%; AD: 15%; Unspecified Dementia: 16% | [40] |

| Longitudinal Study—Baltimore | n = 1686 | NSAIDs | No association was found between AD risk and use of acetaminophen AD risk decreased with increasing duration of NSAID use | RR = 1.35; 95% CI: 0.79–2.30 2 or more years NSAID use, RR:0.40 95% CI: 0.19–0.84; less than 2 years RR: 0.65 95% CI: 0.33–1.29 | [50] |

| Population-based autopsy cohort—ACT Study | n = 257 | NSAIDs | Increased dementia risk | 1000–2000 SDD [RR] 2.16, 95% [CI] 1.02–4.25; >2000 SDD [aRR] 2.37, 95% CI 1.24–4.67 | [45] |

| Nested Case–Control Study UK Biobank | n = 500,000 (age 40–69 yrs) | Opioids | Increased dementia risk Risk increased with more opioid prescriptions | OR (1–5 prescriptions): 1.21 (CI: 1.07–1.37, p: 0.003); OR (6–20 prescriptions): 1.27 (CI: 1.08–1.50, p: 0.003); OR (>20 prescriptions): 1.43 (CI: 1.23–1.67, p < 0.001) | [43] |

| Community-based autopsy cohort—ACT Study | n = 420 | Opioids NSAIDs | The use of prescription opioids does not have a connection with dementia-related neuropathological alterations, although frequent use of NSAIDs may be linked | For neuritic plaques, the aRR [95% CI] was 0.99 [0.64–1.47] for 91+ TSDDs of opioids; heavy NSAID use had a higher risk of neuritic plaques (RR 1.39 [1.01–1.89]) | [46] |

| Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (6 cohort; 3 case–controls) | n = 13,211 (cohorts) n = 1443 (case–controls) (age > 55 yrs) | NSAIDs | Decreased AD risk | Pooled RR for AD:0.72 95% CI: 0.56–0.94 (<1 month) RR: 0.95 CI: 0.70–1.29; (<24 months) RR:0.83 CI: 0.65–1.06; (>24 months) RR: 0.27 CI: 0.13–0.58 | [52] |

| Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (17 epidemiological studies from 8 countries—US, Australia, Canada, China, Finland, Italy, Netherlands, UK) | NSAIDs | Decreased AD risk | Combined OR: 0.55, p < 0.0001 | [49] | |

| A Finnish nationwide nested case–control study MEDALZ | n = 70,718 (mean age 80 yrs) | Opioids | No increased AD risk even for longer duration or higher dose | aOR: 1.00 95% CI: 0.98–1.03 cumulative use for >365 days: aOR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.96–1.08 >90 TSDs: aOR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.98–1.07 | [56] |

| Meta-analysis (16 cohort studies) | n = 236,022 | NSAIDs | Reduced AD risk | Global RR: 0.81 CI: 0.70–0.94; Europe: RR: 0.72; Asia: no association | [57] |

| Prospective Cohort Study-Northwest US | n = 3434 (median age 74 yrs) | NSAIDs Opioids | Individuals who had high levels of opioid or NSAID consumption were found to have a slightly elevated risk of dementia compared to those with minimal or no usage | Cumulative opioid use: HRs for dementia: 1.06 95% CI = 0.88–1.26 for 11 to 30 TSDs; HR: 0.88 (95% CI = 0.70–1.09) for 31 to 90 TSDs; and HR:1.29 (95% CI = 1.02–1.62) for 91 or more TSDs. A similar pattern was seen for NSAID use | [55] |

| Clinical trial double-blind, placebo-controlled study—Northwest Phoenix metropolitan area | n = 44 | NSAID (indomethacin) | Protective against cognitive decline in mild to moderately impaired AD | Improved cognitive tests p < 0.003 | [51] |

| Prospective, population-based cohort study—Rotterdam, Netherlands | n = 6989 (age ≥ 50) | NSAIDs | No association with a reduction in the risk of VD | AD: RR: 0.95 95% CI: 0.70–1.29 (short-term use); RR: 0.83 95% CI: 0.62–1.11 (intermediate-term use); and RR:0.20 95% CI: 0.05–0.83 (long-term use) | [58] |

| Study Type | Population Sample | Effect on Dementia/AD Risk | Statistical Data | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| German Cohort Study | n = 2605, (age > 75 ± 4.5 yrs) | Increased risk of dementia | Dementia: HR: 2.08; AD: HR: 1.63 | [66] |

| UK Case–control study | n = 40,770 (age ≥ 65 yrs) | Dementia was associated with an increasing average ACB score | aOR for any anticholinergic drug with an ACB score of 3 was 1.11 (95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.14) | [67] |

| Population-based Cohort Study— South Korea | n = 550,000 (age ≥ 60 yrs) | AD risk was higher in subjects with an increased number of prescriptions | HR (95% confidence interval (95% CI)) 0.99 (0.95–1.03), 1.19 (1.12–1.26), 1.39 (1.30–1.50); in the 10–49 doses/year, 50–119 doses/year, and ≥120 doses/year groups HR higher in the young-old subgroup (60–64 years old) [HR (95% CI) 1.11 (1.04–1.22), 1.43 (1.25–1.65), 1.83 (1.56–2.14); in the 10–49 doses/year, 50–119 doses/year, and ≥120 doses/year groups | [68] |

| Nested Case–Control Study—UK | n = 284,343 | Higher dementia risk | Antidepressants: aOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.24–1.34, Anti-Parkinson’s drugs: aOR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.16–2.00, Antipsychotics: aOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.53–1.90, Bladder antimuscarinic drugs: aOR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.56–1.75, and Antiepileptic drugs: aOR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.22–1.57 all for more than 1095 TSDDs | [70] |

| Population-based cohort recruited from 3 French cities | n = 6912 (age > 65 yrs) | Increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia | HR: 1.65; 95% CI, 1.00–2.73 | [65] |

| Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (France, UK, Germany, US, Nigeria, Turkey, Netherlands, China, Taiwan) | n = 1,564,18 | Increased risk of ACD and AD (anti-Parkinson’s, urological, antidepressants) Negative association with dementia (anticholinergic cardiovascular and gastrointestinal drugs) No association (antipsychotic, analgesic, and respiratory anticholinergic) | Anti-Parkinson’s (RR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.26–1.53, I2 = 0, 95% CI: 0–90%, p = 0.504), Urological drugs (RR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.12–1.44, I2 = 94.4%, 95% CI: 87%–98%, p < 0.001), and Antidepressants (RR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.15–1.22, I2 = 52.6%, 95% CI: 0–83%, p = 0.077). Anticholinergic cardiovascular (RR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.95−0.996, I2 = 0, 95% CI: 0–90%, p = 0.721) Gastrointestinal (RR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91−0.99, I2 = 48.1%, 95% CI: 0–85%, p = 0.146) | [72] |

| Population-Based Study— Italy | n = 750, (age > 65 yrs) | Cognitive impairment | OR: 3.18 95% CI: 1.93–5.23, p < 0.001 | [73] |

| ADNI cohort | n = 688 (mean age 73.5 yrs) | Increased dementia risk | HR:1.47, p = 0.02 | [75] |

| Prospective and retrospective longitudinal cohort and case–control observational studies | n = 968,428 (age ≥ 65 yrs) | Increased risk of cognitive decline or dementia | OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.96 | [76] |

| Longitudinal Study—England and Wales | n = 13,004 (age ≥ 65 yrs) | Increased cumulative risk of cognitive impairment and mortality | A decline in MMSE score (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.03–0.64, p = 0.03) | [61] |

| A Nationwide 15-Year Follow-Up Cohort Study—Taiwan | n = 790,240 (age > 65 yrs) | No significant association | HR: 1.043 (95% CI: 0.958–1.212, p = 0.139) | [83] |

| Retrospective cohort study used the Humana Research Database | n = 12,209 | Increase AD and dementia risk | 1.6 (95% CI 1.4–1.9), 2.1 (95% CI 1.7–2.8), 2.6 (95% CI 1.5–4.4), and 2.6 (95% CI 1.1–6.3) times increased risk | [80] |

| UK Biobank Cohort study | n = 171,775 | Increase dementia risk | HR: 1.094; 95% CI: 1.068–1.119 | [79] |

| Prospective cohort study conducted within Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPWA) | n = 3059 | Increase AD and dementia risk | 0–90 TSDDs: HR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.18–2.42; 91–365 TSDDs: HR = 1.40, 95% CI = 0.88–2.23; 366–1095 TSDDs: HR = 2.13, 95% CI = 1.32–3.43; ≥1095 TSDDs: HR = 1.42, 95% CI = 0.82–2.46 | [77] |

| Nationwide 12-year cohort study—Taiwan | n = 16,412 (age > 50 yrs) | Bladder anticholinergics increased dementia risk | Dementia aHR 1.15 (95% CI = 0.97–1.37) in the 85–336 cDDD group, and 1.40 (95% CI = 1.12–1.75) in the ≥337 cDDD group | [78] |

| Randomly selected community-based | n = 2058 (age 60–64 yrs) | Anticholinergic medication is associated with lower level of complex attention in the young-old, but not with greater cognitive decline over time | [84] | |

| Prospective cohort study—Seattle, Washington | n = 3434 (age ≥ 65 yrs) | Increased risk for dementia | aHR: 0.92 (95% CI, 0.74–1.16) for TSDDs of 1 to 90; aHR:1.19 (95% CI, 0.94–1.51) for TSDDs of 91 to 365; aHR:1.23 (95% CI, 0.94–1.62) for TSDDs of 366 to 1095; and aHR: 1.54 (95% CI, 1.21–1.96) for TSDDs greater than 1095. A similar pattern for AD | [63] |

| Longitudinal cohort study—Montpellier region of southern France | n = 372 (age > 60 yrs) | Significant cognitive functioning impairments and high chances of being categorized as MCI impaired, with no higher risk of dementia | OR: 5.12, p = 0.001 | [64] |

| Population-based prospective study—Malmo, Sweden | n = 18,063 (mean age 68.2 yrs) | β-blockers not associated with increased risk ACD, AD, and mixed dementia | ACD:HR:1.15; 95% CI 0.80–1.66; p = 0.44; AD:HR:0.85; 95%CI 0.48–1.54; p = 0.59 and Mixed dementia: HR:1.35; 95%CI 0.56–3.27; p = 0.50 | [86] |

| Longitudinal cohort study—Netherlands | n = 133,355 | AHM, ARBs, CCBs, and Ang-II-stimulating AHM were associated with lower dementia risk | ARBs [HR = 0.86 (95% CI = 0.80–0.92)], β-blockers [HR = 0.81 (95% CI = 0.75–0.87)], CCBs [HR = 0.77 (95% CI = 0.71–0.84)], and diuretics [HR = 0.65 (95% CI = 0.61–0.70)] were associated with significantly lower dementia risks; β-blockers [HR = 1.21 (95% CI = 1.15–1.27)] and diuretics [HR = 1.69 (95% CI = 1.60–1.78)] were associated with higher, CCBs with similar, and ARBs with lower [HR = 0.83 (95% CI = 0.80–0.87)] mortality risk. Dementia [HR = 0.88 (95% CI = 0.82–0.95)] and mortality risk [HR = 0.86 (95% CI = 0.82–0.91)] were lower for Ang-II-stimulating drugs | [87] |

| Danish Population-based study | n = 69,081 (median age 64.4 yrs) | Highly permeable β-blockers protect against AD by promoting waste brain metabolite clearance. | −0.45%, p < 0.036 | [88] |

| Study Type | Population Sample | Effect on Dementia/AD Risk | Statistical Data | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-Analysis | n = 45,391 | Long-term BZD users are at a higher risk of developing dementia in comparison to those who have never used the medication | RR: 1.49,95% CI: 1.30–1.72) forever user, RR:1.55 (95% CI 1.31–1.83) for recent users, and RR:1.55 (95% CI 1.17–2.03) for past users. | [101] |

| Longitudinal Study | n = 668 (aged ≥ 75) | Significantly lower incidence of AD in the BDZ+ group | [110] | |

| Population-based Study German population | n = 105,725 (aged ≥ 60) | Increased dementia risk | OR: 1.21 (95% CI: 1.13–1.29, p < 0.001) | [97] |

| Three-city French population-based study | aged ≥ 65 yrs | Linked to lower cognitive ability but not to faster cognitive deterioration as one ages | Chronic use significantly associated with a lower latent cognitive level (β = −1.79 SE = 0.25 p ≤ 0.001) no association was found between chronic use and an acceleration of cognitive decline, (β × time = 0.010 SE = 0.04 p = 0.81), | [102] |

| Retrospective Cohort Study—US | n = 528,006 (aged ≥ 65 yrs) | Slightly raised the risk of dementia compared to not using them, but the risk did not significantly increase with higher exposure levels. | aHR: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.02–1.10) for low BZD exposure, 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.09) for medium BZD exposure, and 1.05 (95% CI 1.02–1.09) for high BZD exposure. | [109] |

| Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses (5) and systematic review (15) | Weak evidence of dementia link | aRR: 1.06 (low users), 1.05 (medium users), 1.05 (high users) | [108] | |

| Case–control study Canadian population | n = 38,741 (age ≥ 65 yrs) | Increased risk of AD | aOR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.36 to 1.69; | [94] |

| A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (Asian, North American, European population) | Increased risk of dementia | Higher association in Asian (OR 2.40; 95% CI 1.66–3.47); moderate association in North American (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.34–1.65) and In European (OR 1.43; 95% CI 1.16–1.75) | [95] | |

| Matched cohort study Finnish population | n = 70,718 | Increased risk of death | aHR = 1.4, 95% CI: 1.2–1.6 | [96] |

| A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | n = 981,133 (in the systematic review) and n = 980,860 (in the meta-analysis) | Can be a risk factor for developing dementia | OR: 1.38, 95% CI: l 1.07–1.77 | [98] |

| A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | n = 159,090 | Increase dementia risk | OR: 1.39, 95%, CI: 1.21–1.59 | [99] |

| Case–Control Study Swiss population | n = 2876 (Mean age 80 ± 7.5 yrs) | No association with increased AD risk | Long-term benzodiazepine use (≥30 prescriptions) aOR: 0.78 (0.53–1.14). | [105] |

| UK-based case–control analysis | n = 26,459 (aged ≥ 65 yrs) | No association with increased AD or VD risk | AD: aOR: 0.69 (0.57–0.85) or VD: aOR: 1.11 (0.85–1.45). | [106] |

| Analytical prospective nested case–control study Spanish population | n = 77,609 | Increased AD risk | OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.10 | [107] |

| Study Type | Population Sample | Effect on Dementia/AD Risk | Statistical Data | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective cohort study—Germany | n = 73,679 (aged ≥ 75 yrs) | Increased dementia risk | HR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.36–1.52; p < 0.001 | [120] |

| Prospective cohort study—US | n = 3484 (aged ≥ 65 yrs) | Not associated with dementia risk, even for people with high cumulative exposure | Dementia (p = 0.66) AD (p = 0.77) | [134] |

| Retrospective study— Veteran population, US | n = 23,656 | Significant association | OR: 1.55 | [121] |

| Nationwide cohort study—Taiwan | n = 1,000,000 (aged ≥ 65 yrs) | Increased dementia risk | aHR: 1.42; 95% CI, 1.07–1.84 | [122] |

| Meta-Analysis | n = 642,305 | No significant AD or dementia risk | Dementia: HR: 1.04 (95% CI: 0.92–1.15) AD: HR: 0.96 (95% CI: 0.83–1.09 p < 0.001) | [10] |

| Longitudinal, multicenter cohort study— Germany | n = 3327 (aged ≥ 75 yrs) | Increased risk of dementia and AD | Dementia: HR: 1.38 (95% CI: 1.04–1.83) AD: HR: 1.44 (95% CI: 1.01–2.06) | [123] |

| Comprehensive Review (8 systematic reviews, 1 clinical trial, 15 observational studies, 3 case–control studies, and 1 cross-sectional observational study) | No link to cognitive decline or dementia | [136] | ||

| A Nationwide Cohort Study—Taiwan | n = 15,726 (aged ≥ 40 yrs) | Increased dementia risk | aHR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.05–1.42 | [125] |

| Finnish Nationwide nested case–control study | n = 282,858 | No clinically meaningful association between PPI use and the risk of AD Higher dose was not associated with an increased risk | 1–3 years of use: aOR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.97–1.06; ≥3 years OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.94–1.04. ≥1.5 defined daily doses: aOR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.92–1.14 | [130] |

| Observational, longitudinal study | n = 12,416 (aged ≥ 50 yrs) | Not associated with a greater risk of dementia or AD | Decline in cognitive function HR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.66–0.93, p = 0.005 Conversion to MCI or AD (HR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.69–0.98, p = 0.03). Intermittent use was also associated with a lower risk of decline in cognitive function (HR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.76–0.93, p = 0.001) and risk of conversion to MCI or AD (HR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.74–0.91, p = 0.001) | [131] |

| Population-based study—UK | n = 3,765,744 (aged ≥ 55 yrs) | PPI use was associated with decreased dementia risk | HR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.65–0.67, p < 0.01. | [132] |

| A systematic review, meta-analysis, and bias analysis from 9 observational cohorts | n = 3,302,778 | No clear evidence | Dementia: RR: 1.15 (95% CI = 1.00–1.31); AD: RR: 1.13 (95% CI = 0.93–1.38) | [133] |

| Community-based retrospective cohorts | n = 135,722 (aged ≥ 45 yrs) | AD was not higher among PPI users, and a slight increase in the risk of non-AD dementia was observed | AD: OR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.18–1.83 non-AD dementias OR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.12–1.70 | [135] |

| Meta-analysis location (European, North American, Asian) | n = 1,251,562 (mean age ≥ 70 yrs) | No association found | HR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.85–1.13 | [137] |

| Large placebo-controlled randomized trial | n = 17,598 (mean age ≥ 65 yrs) | No negative effects related to the use of pantoprazole over 3 years, except for a potentially higher chance of contracting enteric infections | OR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.89–1.50; p = 0.28 | [138] |

| Study Type | Population Sample | Effect on Dementia/AD Risk | Statistical Data | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-varying status of statin use along with the dose–response relationship Korean population | n = 119,013 (≥60 years old) Statin users duration < 540 days | Short-term use linked to increased AD risk; consistent use decreased AD risk | aHR = 1.04; 95%, CI = [0.99–1.10]. Having at least 540 days of statin prescription and a cumulative defined daily dose of at least 540 were linked to a reduced risk of AD [aHR (95% CI) = 0.87 (0.80–0.95) and 0.79 (0.68–0.92), respectively]. | [150] |

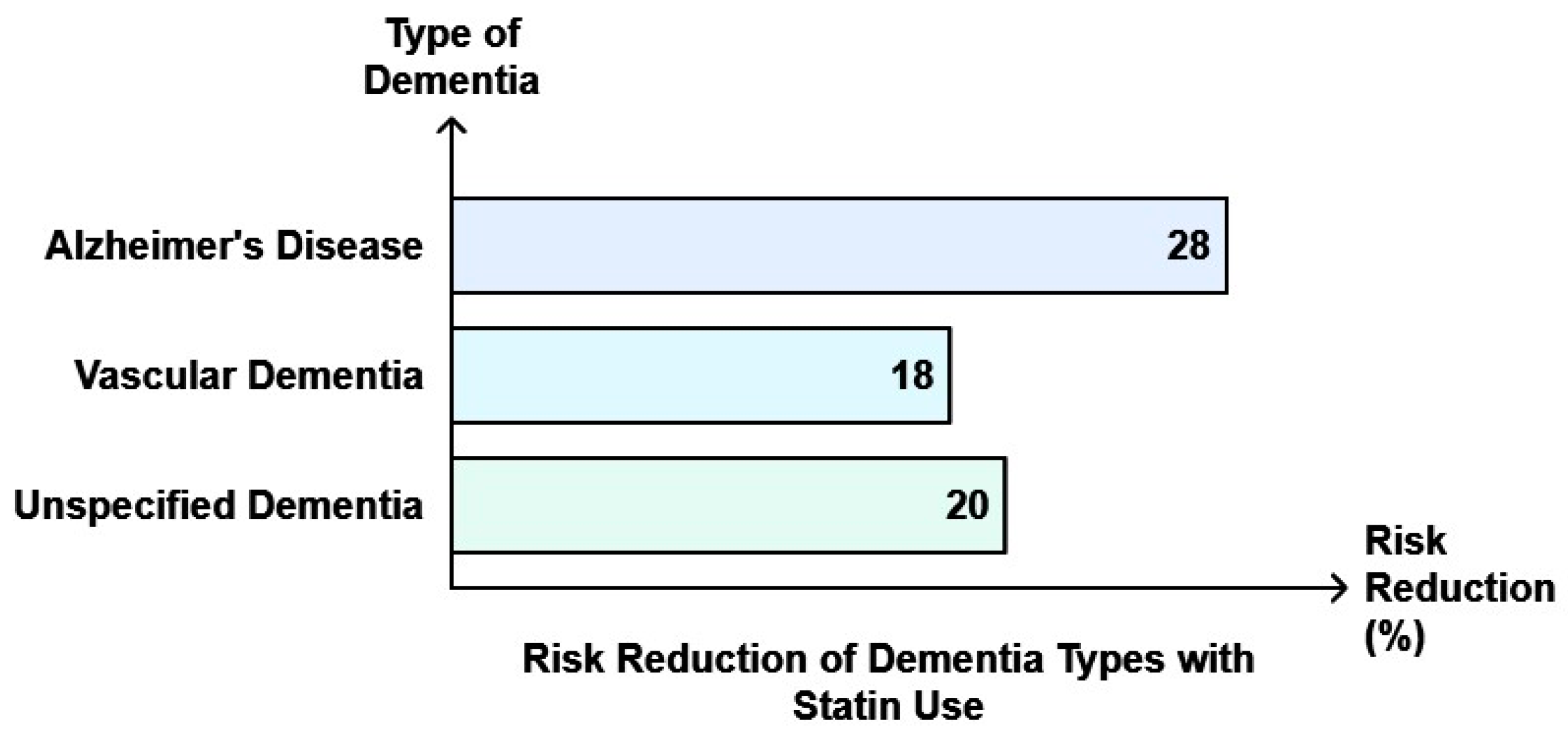

| Meta-Analysis (30 studies) | n = 9,162,509 | Statin use is associated with reduced risks of dementia, AD, and vascular dementia (VD) | Dementia risk: RR:0.83, 95% CI: 0.79–0.87 AD risk: RR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.60–0.80, p < 0. 0001), VD risk: RR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.74–1.16, p = 0.54). | [151] |

| Systematic review of randomized clinical trials (3) and observational studies (21) | n = 1,404,459 (aged ≥ 60 yrs) | No adverse cognitive effects | OR: 1.03 [0.82–1.30] and OR: 1.0 [0.61–1.65] | [152] |

| Nationwide Cohort Study Taiwan | n = 33,398 (aged ≥ 60 yrs) | Reduction in dementia risk in older adults | Dementia: ([HR], 0.78; 95% CI, 0.72–0.85, p < 0.001). | [155] |

| Population-based study—Rotterdam | n = 6992 | Reduction in dementia risk for both lipophilic and hydrophilic statins | AD: HR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.37–0.90), HRs were equal for lipophilic (HR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.32- 0.89) and hydrophilic statins (HR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.26–1.11). | [151] |

| A cohort of older patients receiving polypharmacy | n = 29,047 patients exposed to polypharmacy (mean age 76 yrs) | Stopping statins while continuing other medications led to a rise in the long-term chances of experiencing cardiovascular events, both fatal and nonfatal | In contrast to those who continued the medication, patients who stopped taking it had a higher risk of hospitalizations due to heart failure (HR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.07–1.43) and any cardiovascular events (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.03–1.26), as well as all-cause mortality (HR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.02–1.30) and emergency admissions for any reason (HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.05–1.19). | [159] |

| Population-based retrospective cohort study—Hong Kong | n = 104,295 (mean age 74.2 ± 13.6 yrs) | Reduced AD, VD, and dementia risk | Dementia: (multivariable-adjusted SHR 0.80, 95% CI 0.76–0.84, AD: (SHR 0.72, 95% CI 0.63–0.82), VD: (SHR 0.82, 95% CI 0.70–0.95), unspecified dementia: (SHR 0.80, 95% CI 0.75–0.85). | [160] |

| Nationwide Prospective cohort study— Danish population | n = 674,900 (age > 40 yr) | Increased CVD risk | During follow-up, the Hazard ratios for individuals with vs. without early statin discontinuation were 1.26 (1.21–1.30) for myocardial infarction and 1.18 (1.14–1.23) for death from cardiovascular disease. | [142] |

| Systematic review (60 case reports) | Mean age 62 yrs | Conflicting results | [141] | |

| Community-based prospective cohort study | n = 2356 (age > 65 yrs) | No significant association | ACD: HR:1.33, 95% CI: 0.95–1.85 AD: HR: 0.90, CI: 0.54–1.51 An analysis of a specific subset of participants who had at least one APOE-ε4 allele and joined the study before age 80 revealed aHR: of 0.33, CI: 0.10–1.04. | [143] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, N.; An, S.S.A.; Kim, S.Y. Medication Exposure and Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252312850

Sharma N, An SSA, Kim SY. Medication Exposure and Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(23):12850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252312850

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Niti, Seong Soo A. An, and Sang Yun Kim. 2024. "Medication Exposure and Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 23: 12850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252312850

APA StyleSharma, N., An, S. S. A., & Kim, S. Y. (2024). Medication Exposure and Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(23), 12850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252312850