Abstract

In this note, we suggest the adoption of expert-based approaches for threat analysis to allow an assessment of the magnitude of efforts of wildlife management actions. Similar to what is proposed for expert-based quantification of threat events, in wildlife management this approach can be applied by assigning a score to the extent of the areas affected by management, their frequency and intensity of action, supporting the decision-making process and optimizing the management strategies, both ordinary (for example, in the operational management of nature reserves) and extraordinary (for example, within specific target-oriented conservation projects). Quantifying and defining priority ranks among management events can be useful: (i) to compare managed areas with each other or the same areas in different times; (ii) to adjust the allocation of resources among alternative management actions (assigning more or less resources in terms of time, budget, operators, and technology). Finally, similar to what is done in the threat analysis approach, managers could compare the effort (magnitude) of management at different times. We report, as an example, a first quantification for a case study carried out in a coastal nature reserve.

1. Introduction

In ecology, any event can be characterized by its regime in time and space [1]. This characterization is used in both the quantification of natural disturbances [2] and the analysis of anthropogenic threats [3,4,5,6]. More particularly, we define the term “regime” as the set of attributes (variables or parameters) that characterize a process (in our case, an anthropogenic disturbance event [5]).

The approaches characterizing anthropogenic threats have been mainly based on the evaluation and quantification (either analytical approaches or according to expert-based methods) of regimes of threats, for instance, considering the extent, frequency, duration, and intensity in order to obtain an overall value of impact (i.e., their magnitude). This approach, although criticized, has been adopted in many conservation contexts and appears effective to rank priorities in conservation (for review, see Reference [7]).

In our opinion, these evaluation approaches can be applied not only to such actions as anthropogenic threats but also to any event deliberately caused to carry out management actions (for example, restoration projects carried out by agencies, etc.). Indeed, since both “threats” and “management actions” are human-induced processes, similar to what is proposed for expert-based quantification of threats, where these activities are assessed assigning (and summing) scores to their extent, duration, frequency, and intensity [5], in wildlife management we can assign a score to the extent of the areas affected by management, their duration and frequency, and, finally, the intensity of action. Since managers of conservation areas lack tools for measuring how they allocate management resources, these scores may support the decision-making process and adjust the management strategies, both ordinary (for example, in the operational management of nature reserves; [8]) and extraordinary (for example, within specific target-oriented conservation projects; [5]). The quantification and the definition of a rank of priorities among management events can be useful: (i) to compare managed areas with each other or the same areas at different times; (ii) to adjust ordinary or extraordinary management actions (that is assigning more or less resources in terms of time, budget, operators, technology).

In this regard, we aimed with this article at suggesting the adoption of the approaches in use for the analysis of threats also to allow an assessment of the magnitude of effort of wildlife management activities. More particularly, in this regard, we refer to “magnitude” as the amount of management effort (i.e., output) that has been devoted for each management action carried out by a park agency managing a nature reserve as an example, and we reported a first quantification in a case study (a coastal nature reserve).

2. Methods

2.1. Case Study

The study area corresponded to the “Palude di Torre Flavia” natural monument, a small protected coastal Mediterranean wetland (40 ha; Special Area of Conservation, according to the EC Directive on the Conservation of Wild Bird 79/409/EEC; code IT6030020) which is a relic of a larger wetland drained and transformed by land reclamation in the last century located along the Tyrrhenian coast of Central Italy (Latium; Municipalities of Cerveteri and Ladispoli; 41°58’ N; 12°03’ E) [9,10]. This reserve was established in 1997 to protect a large number of wet habitats and related breeding and wintering migratory birds. Indeed, in this area >180 species of birds have been censused with 40 species of high conservation concern (some of them “near threatened” or “critically endangered” following the IUCN (World Conservation Union) red list and included in 147/2009/“Wild Bird” EC Directive: among them Charadrius alexandrinus, linked to sandy beaches, and Botaurus stellaris, Ixobrychus minutus, Nycticorax nycticorax, Ardeola ralloides, Plegadis falcinellus, Aythya nyroca linked to salt marshes and ponds). The recent “measures of conservation” of this reserve (Città Metropolitana di Roma Capitale, 2010, unpublished data) focused on the conservation of a sufficient status of the species included in Wild Bird Directive through a set of measures (mainly: habitat restoration and threat mitigation).

The vegetation is characterized by both saline and hygrophilous vegetation related to temporary and semi-temporary ponds. Along the coast, dunal environments are present which host the endangered bird species [9].

The area has been managed since 1997 by a Public Agency (Città Metropolitana Roma Capitale, Rome, Italy) through an operational staff composed of two technicians and two practitioner operators who know the occurrence of the different ordinary management actions that take place there. Ordinary management activities in the Torre Flavia nature reserve can be grouped into the following categories: (1) regulation, administration, and logistics; (2) Fruition (i.e., actions focused on guaranteeing the reserve is available for use through access points, paths, and visitor centers); (3) control; (4) conservation education; (5) communication; (6) training; (7) ordinary management of environmental components; (8) conservation; (9) research; (10) other activities.

2.2. Protocol

As mentioned above, in analogy to what happens when treating a threat regime [7], defining a range of attributes is an important step. Such attributes allow the definition of the total management effort, i.e., its magnitude. Among the different regime attributes (see Reference [7]), we selected three: extent, frequency (around an annual cycle), and intensity. More particularly: (I) Extent: according to Reference [11], extent represents the spatial or temporal range where activities, actions, or events occur. Scores: 4: the whole management area; 3: >75% of the area; 2: from 25 to 50%; 1: <25%; (II) Frequency: this indicates the number of anthropogenic events (in our case management actions) within the time unit. Scores: 4: daily; 3: weekly; 2: monthly; 1: annually; (III) Intensity (or severity): in threat analysis, and according to Reference [5], this term is indirectly connected to the degree of a target’s damage/alteration (impact) which can be expected within specific circumstances. Applying this attribute to management actions, we can define “intensity” as the direct effort (excluding extent and frequency) necessary to have a potential positive impact on defined management targets regardless of the real outcomes on the different management targets. Scores: 4: very high management intensity (in terms of costs, technology, materials, operators involved); 3: high; 2: medium; 1: low.

We summed the abovementioned management attributes in a single final score named “Magnitude”. In threat analysis, magnitude represents the capacity of a threat event to exert a pressure or an impact [10]. As such, this attribute is strictly dependent on the threat regime itself. Similar to the other attributes, in the absence of field or experimental data, magnitude can be calculated through the sum of scores assigned by skilled practitioners following an expert-based method. More in particular, magnitude is obtained by summing the regime attribute utilized [5]. In our case, we summed the scores obtained for the three selected regime attributes, i.e., extent, frequency, and intensity. Therefore, in our approach, management magnitude could represent the degree of a total effort (output management) devoted to an activity in terms of extent, frequency, and intensity. From a project management perspective, this effort can be considered the project output, or the set of energies dedicated to carrying out a series of actions for a specific category of activity, (see Reference [8]). It should not be confused with the project outcomes (i.e., with the effective results of the actions on the environmental components) which, in this case, are not measured.

To assign scores, we involved four operators having a comparable role (all management operators) and a large knowledge (>10 years) of management actions carried out yearly in the nature reserve (see Acknowledgments).

First, we selected the set of management actions (n = 35), grouped in 10 categories, to which the scores will be attributed (Table 1). Secondly, we built an “action/attribute” evaluation matrix that was submitted to operators who independently evaluated the extent, frequency, and intensity of each management action. The scores were subsequently added up obtaining a magnitude score, and the mean value (and standard deviation) was calculated. Therefore, magnitudes were ranked across 35 management actions using the scores provided by each of the four observers.

Table 1.

List of (ordinary) management actions carried out in the “Torre Flavia” nature reserve (Special Protection Area). For each activity, a short description is reported.

For some actions (e.g., fences, signs, social media, research) the intensity score was assigned by evaluating the collective effort made by operators to achieve that specific output (e.g., for social media: effort to design communication strategy; for research: effort devoted to define protocols, experimental design, and data analyses). The comparison of the average magnitude values among the various actions was calculated using Friedman test [12]. The alpha was set at the 0.05 level. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software.

3. Results

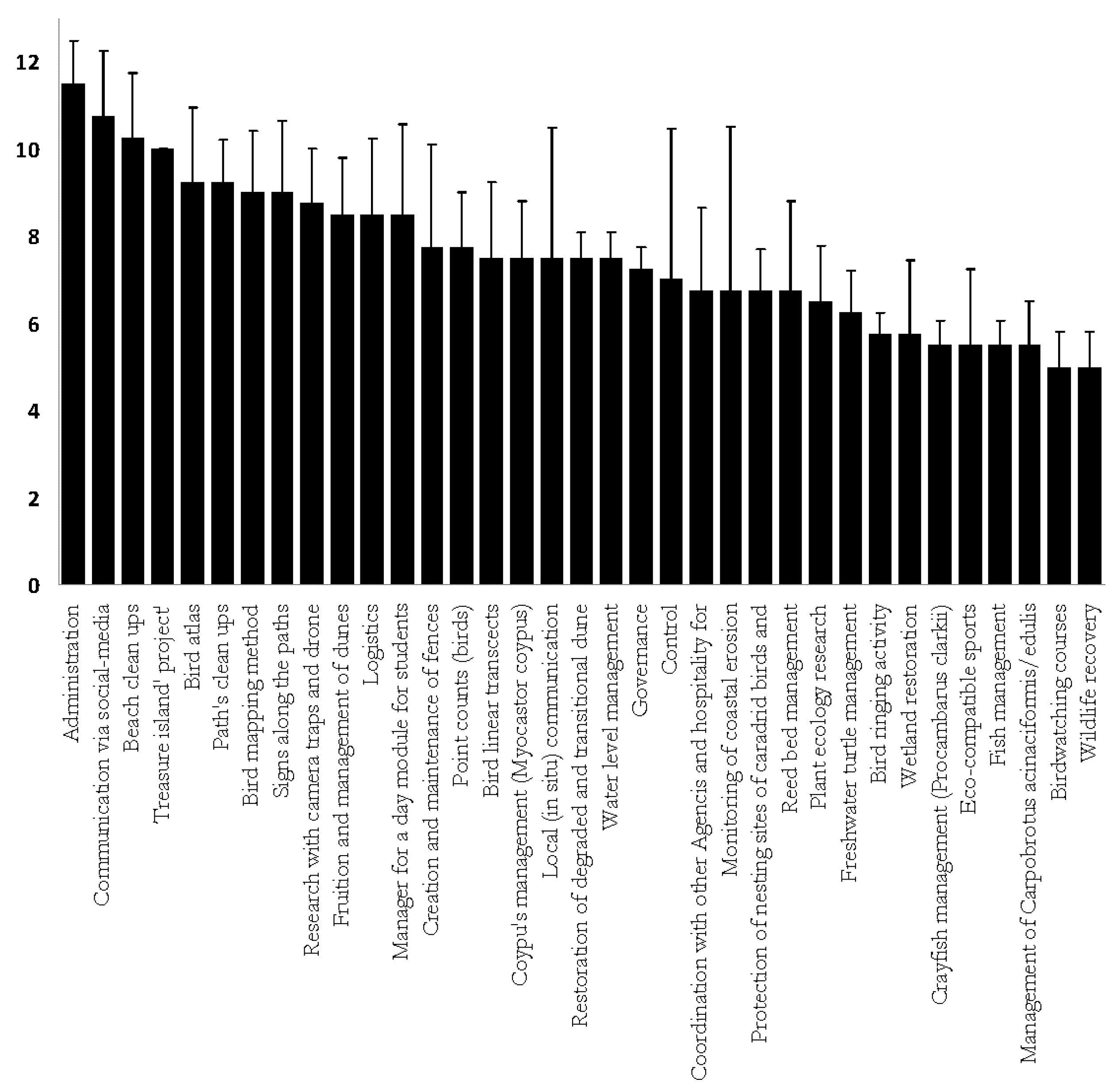

The mean magnitude scores for each attribute calculated for each management action are shown in Figure 1. In our case study of ordinary management of a protected area, we observed a significant difference among management actions (χ2 = 83.186, p < 0.001; d.f. 34, Friedman test) with administration, communication, and beach clean ups being the actions demanding the most effort (mean magnitude > 10) and bird-watching courses and wildlife rehabilitation being the actions demanding the least effort (≤ 5) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Mean magnitude scores (and standard deviations) for the management actions selected.

Table 2.

Mean magnitude score for the management actions (and categories, in bold) selected for the case study (Torre Flavia wetland nature reserve).

4. Discussion

In wildlife management and conservation, the evaluation of management effort is of priority relevance [13,14] and a large number of approaches have been used as decision-support tools to prioritize actions in conservation projects by following different criteria (for example: Triage: [15]; Eisenhower matrix: [16]). In this case, we treated the individual management actions of a case study (ordinary management of a protected area) as activities each one carried out with an effort expended (magnitude = management output) and addressed to obtain a specific effect (i.e., a potential positive impacts = outcomes) on the environmental targets. Similar to what is suggested in the case of analysis of threat events, for which it is possible to quantify the magnitude of impact through the assignment of scores by experts to regime attributes ([5,10]; reviewed in Reference [7]), also in this case it was possible to quantify the total effort (= impact magnitude) considering a series of regime attributes.

The abovementioned approach can be useful to know the potential impact (expressed as a magnitude score) of the various actions, in terms of management effort, both ordinary (e.g., ordinary management of a protected area) and extraordinary within a project cycle (e.g., problem-solving and management through projects). For example, this method can be used to compare management efforts between different protected areas (for example, nature reserve systems managed by a single agency). Furthermore, chief managers could use this approach to better target (i.e., to balance) the different management or project activities. For example, in our case a high magnitude of the administrative sector emerged, given the critical state of the protected area (where many threats impact on targets of conservation interest). This indication can adjust our management strategy; indeed, it might be more appropriate to exercise a higher management magnitude towards operational activities aimed at controlling some environmental processes in progress (coastal erosion, control of alien species). Finally, similar to what is done in areas of conservation concern through threat analysis (see Reference [17]), managers could compare the effort (magnitude) of management at different times.

However, this approach can be even more complex and detailed. First: the evaluation can also use other attributes of management activities (duration, reversibility, predictability, urgency, importance; reviewed in Reference [7]). Second, further details may be added to assign specific weights of relative importance of individual attributes, if circumstances require it [18]. When managers adopt this approach, they should also examine which of the three variables might be more important or reflective of what is attempting to be measured and possibly change the simple equal weighting, not just accepting this preliminary simple index of effort. Third, we used a simple expert-based procedure obtaining average values provided by a limited number of operators on the assumption that combining the expertise of several individuals will provide more reliable results than consulting few individuals. Fourth, our approach calculated only the management effort (outputs) and further analyses could be devoted to obtaining scores about the real effectiveness on conservation targets (management outcomes). In this work, our aim was understanding where the total management effort is addressed, independently from the real effectiveness on conservation targets (biodiversity) and a comparison between management effort (outputs) and real effectiveness (outcomes) could be important to evaluate the role of management agency and their real role as conservation organization (i.e., measuring effort is just one step, but measuring real outcomes is important for the mission of a park agency). Finally, you can adopt other approaches (for example, Delphi techniques performed to develop consensus among experts over several rounds of deliberation, known as “open Delphi”; [19]). Moreover, management evaluation can be implemented using graphical approaches, for example, through n × n matrices and graphs (for threats: e.g., [20]), widely used in environmental project management [21]. Last but not least, since this approach can be useful to effectively address management budgets and resources, we think that this approach using discrete variables may be included in the disciplinary context of discrete optimization problems [22], aimed at finding the best solution from all feasible solutions (in our case, highlighting what are the management actions for which the greatest effort is dedicated and, if necessary, direct it towards conservation priorities). Our case study revealed that the public park agency devoted the largest share of effort to administration and less effort to true conservation practices. Such allocation of resources away from conservation has been denounced by wildlife practitioners [23,24]; our proposed scoring method allows potential resource misallocation to be quantified and evaluated.

Author Contributions

C.B. and L.L. contributed to the article through conceptualization of the problem, development of methodology, data collection and analyses, and original draft preparation. All authors participated in writing—review & editing. C.B. participated in the score evaluation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication did not receive funds.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Carlo Galimberti and Egidio Trucchia (operators in the Torre Flavia wetland nature reserve) for their participation to the working groups as expert members. Alex Zocchi reviewed the English style and language. Two anonymous reviewers provided useful comments and suggestions that improved the first and second draft of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lytle, D.A.; Poff, N.L. Adaptation to natural flow regimes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, W.P. The role of disturbance in natural communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1984, 15, 353–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N.; Landres, P.B. Threats to wilderness ecosystems: Impacts and research needs. Ecol. Appl. 1996, 6, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Kolasa, J.; Armesto, J.J.; Collins, S.L. The ecological concept of disturbance and its expression at various hierarchical levels. Oikos 1989, 54, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salafsky, N.; Salzer, D.; Stattersfield, A.J.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Neugarten, R.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Collen, B.; Cox, N.; Master, L.L.; O’Connor, S.; et al. A standard lexicon for biodiversity conservation: Unified classifications of threats and actions. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurant, G. The Ecology of Natural Disturbance and Patch Dynamics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, C.; Poeta, G.; Fanelli, G. An Introduction to Disturbance Ecology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hockings, M.; Stolten, S.; Leverington, F.; Dudley, N.; Courrau, J. Evaluating Effectiveness: A Framework for Assessing the Management of Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, C.; Aglitti, C.; Sorace, A.; Trotta, M. Water level and its effect on the breeding bird community in a remnant wetland in Central Italy. Ekològia (Bratisl.) 2006, 25, 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, C.; Luiselli, L.; Pantano, D.; Teofili, C. On threats analysis approach applied to a Mediterranean remnant wetland: Is the assessment of human-induced threats related into different level of expertise of respondents? Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 16, 1529–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, J. WWF Rapid Assessment And Prioritization of Protected Area Management (RAPPAM) Methodology; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dytham, C. Choosing and Using Statistics: A Biologist’s Guide; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hockings, M. Systems for assessing the effectiveness of management in protected areas. BioScience 2003, 53, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.K.; McDuff, M.D.; Monroe, M.C. Conservation Education and Outreach Techniques; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Leverington, F.; Hockings, M.; Costa, K.L. Management Effectiveness Evaluation in Protected Areas: A Global Study; University of Brisbane: Brisbane, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bottrill, M.C.; Joseph, L.N.; Carwardine, J.; Bode, M.; Cook, C.; Game, E.T.; Grantham, H.; Kark, S.; Linke, S.; McDonald-Madden, E.; et al. Is conservation triage just smart decision making? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.C.; Lee, Y.Y. Strategic planning for land use under extreme climate changes: A case study in Taiwan. Sustainability 2016, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salafsky, N.; Margoluis, R. Threat reduction assessment: A practical and cost-effective approach to evaluating conservation and development projects. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasolo, W.K.; Temu, A.B. Tree species selection for buffer zone agroforestry: The case of Budongo Forest in Uganda. Int. For. Rev. 2008, 10, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, D.C.; Marshall, K. The Delphi process–an expert-based approach to ecological modelling in data-poor environments. Anim. Conserv. 2006, 9, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.N. The Wilderness Threats Matrix: A Framework for Assessing Impacts; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain: Ogden, UT, USA, 1994; 14p.

- Battisti, C. Unifying the trans-disciplinary arsenal of project management tools in a single logical framework: Further suggestion for IUCN project cycle development. J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 41, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Pressey, R.L.; Faith, D.P.; Margules, C.R.; Fuller, T.; Stoms, D.M.; Moffett, A.; Wilson, K.A.; Williams, K.J.; Williams, P.H.; et al. Biodiversity conservation planning tools: Present status and challenges for the future. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 123–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C.; Franco, D.; Luiselli, L. Searching the conditioning factors explaining the (In)Effectiveness of protected areas management: A case study using a SWOT Approach. Environ. Pract. 2013, 15, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).