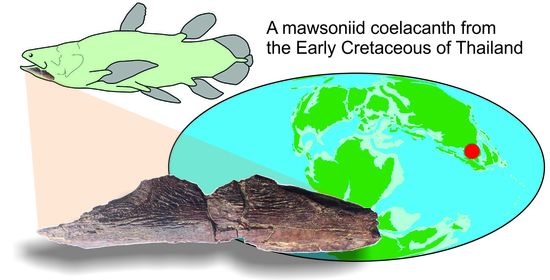

The First Fossil Coelacanth from Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Geological and Paleoenvironmental Settings

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Systematic Paleontology

4.1.1. Description

- The state of preservation of the left angular PRC 160 (Figure 2) is fairly good, except for some breaks in its mid-length and along its ventral side. Moreover, matrix that cannot be removed because of fragility of the bone obscures some details of its medial (lingual) face. A dermal skull bone, likely belonging to the same individual, is still attached with matrix to the posterior part of the medial side. Although incompletely preserved, the general outline of the angular corresponds to a rather shallow bone, with its length a little more than four times its depth. The posterodorsal margin of the bone is poorly preserved, and its anterodorsal margin is almost straight. The coronoid eminence, located at the anterior third of the bone, is very slightly inclined forward. The sutural surface with the principal coronoid is small, but well defined. The lateral (labial) side is ornamented with a dense pattern of reticulated ridges oriented along the anteroposterior axis of the bone in its mid-depth and oriented toward the coronoid eminence in the anterodorsal region of the bone. The overlap surface for the dentary is visible as a slight concavity dug in the labial side along the anterodorsal margin, extending almost to the coronoid eminence. The ornamentation on this sutural surface, composed of anastomosed ridges smaller than those on the rest of the bone, is more noticeable than that in other mawsoniids. The ventral margin of the bone is inwardly curved, and this region is almost devoid of ornamentation. The ventral side of the angular is poorly preserved, obscuring the pattern of the mandibular sensory canal. A large posterior opening corresponding to the entrance of the mandibular sensory canal is present, visible in lateral and ventral views (Figure 2). In the ventral view, several pores are visible in the posterior third of the bone, but it is difficult to determine their number and shape. More anteriorly, the pores are likely present but not visible because of preservation. On the lingual face, the adductor fossa is well developed and marked by a pronounced ridge along its ventral margin. The longitudinal fossa, located on the posterior part of the bone, is only visible thanks to a ridge that marks its anterodorsal margin. The rest of the fossa is covered by matrix and by the dermal skull bone, which also prevents seeing whether a sutural surface for the prearticular is present or not.

- An isolated bone, squarish to ovoid in shape, is attached by matrix to the posterior part of the angular. The natural margins of the bone are not well preserved, preventing its precise identification. Its surface is ornamented with a reticulation of bulbous ridges, pretty different from the diverging ridges of the angular. This difference in ornamentation between the skull roof and cheek bones, including the angular bone, however, is typical of what is observed in mawsoniid coelacanths. Consequently, we consider that this ossification likely belongs to the same individual as the angular, and it was tentatively identified as a supraorbital because of its general rectangular shape and its ornamentation being more pronounced than the ornamentation on the bones of the median series (parietals, nasals).

4.1.2. Comparisons and Identification

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mawson, J.; Woodward, A.S. Cretaceous formation of Bahia and its vertebrate fossils. Q. J. Geol. Soc. 1907, 63, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maisey, J.G. Coelacanths from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Am. Mus. Novit. 1986, 2866, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yabumoto, Y. A new coelacanth from the Early Cretaceous of Brazil (Sarcopterygii, Actinistia). Paleontol. Res. 2002, 6, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Cupello, C.; Batista, T.A.; Fragoso, L.G.; Brito, P.M. Mawsoniid remains (Sarcopterygii: Actinistia) from the lacustrine Missão Velha Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Araripe Basin, North-East Brazil. Cretac. Res. 2016, 65, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, T.A.; Bantim, R.A.M.; de Lima, F.J.; dos Santos Filho, E.B.; Saraiva, A.Á.F. New data on the coelacanth fish-fauna (Mawsoniidae) from the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous of Araripe Basin, Brazil. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2019, 95, 102280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.; de Carvalho, M.S.S.; Maisey, J.G.; Perea, D.; Da Silva, J. Coelacanth remains from the Late Jurassic–?earliest Cretaceous of Uruguay: The southernmost occurrence of the Mawsoniidae. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2012, 32, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toriño, P.; Soto, M.; Perea, D.; de Carvalho, M.S.S. New findings of the coelacanth Mawsonia Woodward (Actinistia, Latimerioidei) from the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous of Uruguay: Novel anatomical and taxonomic considerations and an emended diagnosis for the genus. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2021, 107, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, W. Ergebnisse der Forschungsreisen Prof. E. Stromers in den Wüsten Ägyptens. II. Wirbeltierreste der Baharîje-Stufe (unterstes Cenoman). Neue Untersuchungen an den Fishresten. Abh. Der Bayer. Akad. Der Wissenschaften. Math.-Nat. Abt. 1935, Neue Folge, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tabaste, N. Etude de restes de poissons du Crétacé saharien. Mémoire IFAN Mélanges Ichthyol. 1963, 68, 437–485. [Google Scholar]

- Wenz, S. Un nouveau coelacanthidé du Crétacé inférieur du Niger, remarques sur la fusion des os dermiques. In Proceedings of the Colloque international CNRS, Problèmes actuels de paléontologie-évolution des vertébrés, Paris, France, 4–6 June 1975; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Wenz, S. Un coelacanthe géant, Mawsonia lavocati Tabaste, de l’Albien-base du Cénomanien du sud marocain. Ann. Paléontologie 1981, 67, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yabumoto, Y.; Uyeno, T. New materials of a Cretaceous coelacanth, Mawsonia lavocati Tabaste from Morocco. Bull. Natl. Sci. Mus. 2005, 31, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cavin, L.; Forey, P.L. New mawsoniid coelacanth (Sarcopterygii: Actinistia) remains from the Cretaceous of the Kem Kem beds, SE Morocco. In Mesozoic Fishes III—Systematics, Plaeoenvironments and Biodiversity; Tintori, A., Arratia, G., Eds.; Dr Pfeil Verlag: München, Germany, 2004; pp. 493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Casier, E. Matériaux pour la faune ichthyologique Eocrétacique du Congo. Annales du Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale-Tervuren, Belgique, série 8. Sci. Géologiques 1961, 39, 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, P.M.; Cupello, C.; Yabumoto, Y.; Hell, J.V.; Brunet, M.; Otero, O. First occurrence of a mawsoniid (Sarcopterygii: Actinistia), Mawsonia soba sp. nov., in pre-Aptian Cretaceous deposits from Cameroon. Cretac. Res. 2018, 86, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forey, P.L. History of the Coelacanth Fishes; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, M.D.; Rogers, R.R.; Curry Rogers, K. First record of Late Cretaceous coelacanths from Madagascar. In Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates; Arratia, G., Wilson, M.V.H., Cloutier, R., Eds.; Dr Pfeil Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2004; pp. 687–691. [Google Scholar]

- Cavin, L.; Forey, P.L.; Buffetaut, E.; Tong, H. Latest European coelacanth shows Gondwanan affinities. Biol. Lett. 2005, 2005, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavin, L.; Valentin, X.; Garcia, G. A new mawsoniid coelacanth (Actinistia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Southern France. Cretac. Res. 2016, 62, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavin, L.; Buffetaut, E.; Dutour, Y.; Garcia, G.; Le Loeuff, J.; Méchin, A.; Méchin, P.; Tong, H.; Tortosa, T.; Turini, E.; et al. The last known freshwater coelacanths: New Late Cretaceous mawsoniid remains (Osteichthyes: Actinistia) from Southern France. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavin, L. Palaeobiogeography of Cretaceous Bony Fishes (Actinistia, Dipnoi and Actinopterygii). In Fishes and the Breakup of Pangaea; Cavin, L., Longbottom, A., Richter, M., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2008; Volume 295, pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cavin, L.; Toriño, P.; Van Vranken, N.; Carter, B.; Polcyn, M.J.; Winkler, D. The first late Cretaceous mawsoniid coelacanth (Sarcopterygii: Actinistia) from North America: Evidence of a lineage of extinct ‘living fossils’. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, X.; Amiot, R.; Boura, A.A.; Cavin, L.; Martín-Closas, C.; Gobé, J.-F.; Godefroit, P.; Gomez, B.; Daviero-Gomez, V.; Otero, O. The fossil locality of Persac (Vienne, France): A unique window on a 100 million years old continental ecosystem. In Proceedings of the 27ème Réunion des Sciences de la Terre, Lyon, France, 1–5 November 2021; Available online: https://hal.inria.fr/hal-03720210/ (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Cuny, G.; Liard, R.; Deesri, U.; Liard, T.; Khamha, S.; Suteethorn, V. Shark faunas from the Late Jurassic—Early Cretaceous of northeastern Thailand. Paläontologische Z. 2014, 88, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, H.; Chanthasit, P.; Naksri, W.; Ditbanjong, P.; Suteethorn, S.; Buffetaut, E.; Suteethorn, V.; Wongko, K.; Deesri, U.; Claude, J. Yakemys multiporcata ngn sp., a Large Macrobaenid Turtle from the Basal Cretaceous of Thailand, with a Review of the Turtle Fauna from the Phu Kradung Formation and Its Stratigraphical Implications. Diversity 2021, 13, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deesri, U.; Suteethorn, V.; Liard, R.; Cavin, L. First discovery of a juvenile Thaiichthys (Actinopterygii: Holostei) from the Late Jurassic—Early Cretaceous of Thailand. J. Sci. Technol. Mahasarakham Univ. 2014, 33, 357–364. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H.; Claude, J.; Naksri, W.; Suteethorn, V.; Buffetaut, E.; Khansubha, S.; Wongko, K.; Yuangdetkla, P. Basilochelys macrobios n. gen. and n. sp., a large cryptodiran turtle from the Phu Kradung Formation (latest Jurassic-earliest Cretaceous) of the Khorat Plateau, NE Thailand. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2009, 315, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.E.; Lauprasert, K.; Buffetaut, E.; Liard, R.; Suteethorn, V. A large pholidosaurid in the Phu Kradung Formation of north-eastern Thailand. Palaeontology 2014, 57, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffetaut, E.; Suteethorn, V. A sinraptorid theropod (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Phu Kradung Formation of northeastern Thailand. Bull. Société Géologique Fr. 2007, 178, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, E.D. Contribution to the ichthyology of the Lesser Antilles. Trans. Am. Philos. Soc. 1871, 14, 445–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, H.-P. Osteichthyes: Sarcopterygii. In The Fossil Record 2; Benton, M.J., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1993; pp. 657–663. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.S.S.; Maisey, J.G. New occurrence of Mawsonia (Sarcopterygii: Actinistia) from the Early Cretaceous of the Sanfranciscana Basin, Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil. In Fishes and the Break-up of Pangaea; Special Publications; Cavin, L., Longbottom, A., Richter, M., Eds.; Geological Society: London, UK, 2008; Volume 295, pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cavin, L.; Cupello, C.; Yabumoto, Y.; Fragoso, L.; Deesri, U.; Brito, P.M. Phylogeny and evolutionary history of mawsoniid coelacanths. Bull. Kitakyushu Mus. Nat. Hist. Hum. Hist. Ser. A 2019, 17, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, W.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Hu, S.-X.; Benton, M.J.; Zhou, C.-Y.; Tao, X.; Huang, J.-Y.; Chen, Z.-Q. Coelacanths from the Middle Triassic Luoping Biota, Yunnan, South China, with the earliest evidence of ovoviviparity. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 2013, 58, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geng, B.-H.; Zhu, M.; Jin, F. A revision and phylogenetic analysis of Guizhoucoelacanthus (Sarcopterygii, Actinistia) from the Triassic of China. Vertebr. PalAsiatica 2009, 47, 311–329. [Google Scholar]

- Toriño, P.; Soto, M.; Perea, D. A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of coelacanth fishes (Sarcopterygii, Actinistia) with comments on the composition of the Mawsoniidae and Latimeriidae: Evaluating old and new methodological challenges and constraints. Hist. Biol. 2021, 33, 3423–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabumoto, Y.; Brito, P.M. A New Triassic Coelacanth, Whiteia oishii (Sarcopterygii, Actinistia) from West Timor, Indonesia. Paleontol. Res. 2016, 20, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavin, L.; Piuz, A.; Ferrante, C.; Guinot, G. Giant Mesozoic coelacanths (Osteichthyes, Actinistia) reveal high body size disparity decoupled from taxic diversity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisey, J.G. Continental break up and the distribution of fishes of Western Gondwana during the Early Cretaceous. Cretac. Res. 2000, 2000, 281–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutel, H.; Pennetier, E.; Pennetier, G. A giant marine coelacanth from the Jurassic of Normandy, France. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2014, 4, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutel, h.; Herbin, M.; Clément, G. First occurrence of a mawsoniid coelacanth in the Early Jurassic of Europe. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2015, 35, e929581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toriño, P.; Gausden, S.F.; Etches, S.; Rankin, K.; Marshall, J.E.; Gostling, N.J. An enigmatic large mawsoniid coelacanth (Sarcopterygii, Actinistia) from the Upper Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay Formation of England. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2022, 42, e2125813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyaud, L.; Wirjoatmodjo, S.; Rachmatika, I.; Tjakrawidjaja, A.; Hadiaty, R.; Hadie, W. Une nouvelle espèce de coelacanthe. Preuves Génétiques Et Morphol. 1999, 322, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kadarusman; Sugeha, H.Y.; Pouyaud, L.; Hocdé, R.; Hismayasari, I.B.; Gunaisah, E.; Widiarto, S.B.; Arafat, G.; Widyasari, F.; Mouillot, D.; et al. A thirteen-million-year divergence between two lineages of Indonesian coelacanths. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cavin, L.; Alvarez, N. Why coelacanths are almost “Living Fossils”? Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavin, L.; Tong, H.; Buffetaut, E.; Wongko, K.; Suteethorn, V.; Deesri, U. The First Fossil Coelacanth from Thailand. Diversity 2023, 15, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020286

Cavin L, Tong H, Buffetaut E, Wongko K, Suteethorn V, Deesri U. The First Fossil Coelacanth from Thailand. Diversity. 2023; 15(2):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020286

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavin, Lionel, Haiyan Tong, Eric Buffetaut, Kamonlak Wongko, Varavudh Suteethorn, and Uthumporn Deesri. 2023. "The First Fossil Coelacanth from Thailand" Diversity 15, no. 2: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020286

APA StyleCavin, L., Tong, H., Buffetaut, E., Wongko, K., Suteethorn, V., & Deesri, U. (2023). The First Fossil Coelacanth from Thailand. Diversity, 15(2), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15020286