Resin Infiltration in Dental Fluorosis Treatment—1-Year Follow-Up

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- isolation with dental dam, hooks and accessories devices (dental floss, wedges, transparent matrices) where needed;

- -

- cleaning of dental surfaces with a prophylaxis paste without fluoride;

- -

- etching of lesions with 15% hydrochloric acid (Icon etch, DMG) for 120 s;

- -

- rinsing of surfaces with abundant water for 30 s and drying with air jet;

- -

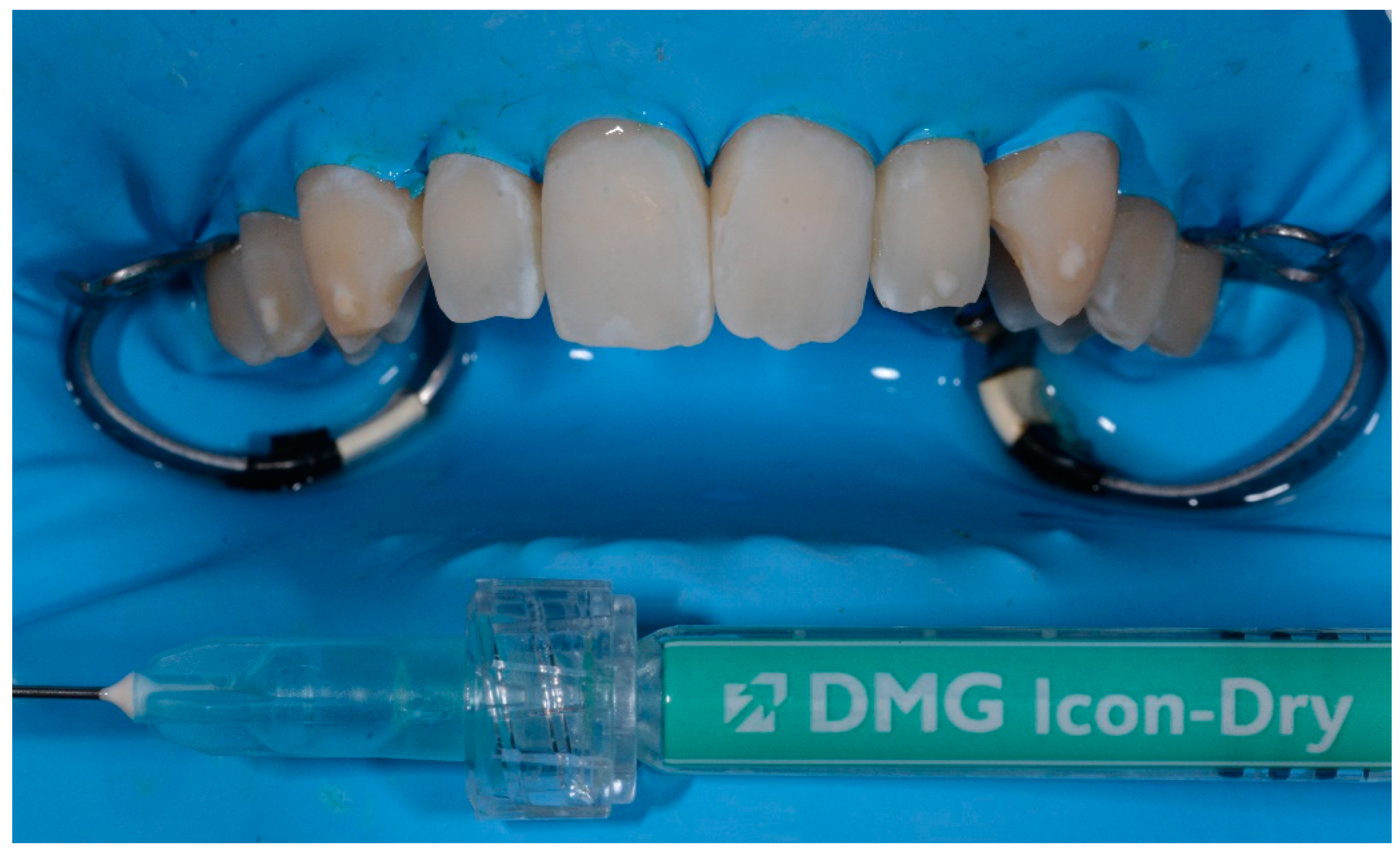

- application of 99% pure ethanol (Icon-Dry, DMG) for 30 s; (Figure 1)

- -

- assessment of needing for further etching cycles by the operator

- -

- completed the drying of surfaces, application of infiltrating resin (Icon Infiltrant; DMG) left in position for 3 min; (Figure 2)

- -

- elimination of excess material using cotton pellets in vestibular portion and dental floss in interproximal areas, thus photopolymerization with UV lamp for 40 s;

- -

- second infiltration of resin, left in position for 1 min and polymerized for 40 s

- -

- polishing of surfaces, check of contact points and finishing with abrasive stripes in interproximal areas requiring. (Figure 3)

- (a)

- Aesthetic dissatisfaction for lesions (VAS scale, 0: indifferent, 10: highly unsatisfied)

- (b)

- Shiff Air Index Sensitive Scale (after treatment) [21]

- (c)

- Sensitive teeth reported (after 72 h)

- (d)

- Satisfaction of the duration of treatment (VAS scale, 0: not satisfied, 10: highly satisfied)

- (e)

- Pain during treatment (VAS scale)

- -

- TSIF

- -

- The main dimension of lesions (mm)

- -

- Etching cycles needed

- -

- -

- -

Statistical Analysis

- -

- Dimension of lesions at t0 and t1

- -

- TSIF at t0 and t1

- -

- Dental sensitivity values after 72 h of treatment

- -

- Pain during treatment

- -

- Aesthetic dissatisfaction for lesions at t0 and t1

- -

- Aesthetic dissatisfaction for lesions at t1 and t2

- -

- Aesthetic dissatisfaction for lesions at t2 and t3

- -

- Aesthetic dissatisfaction for lesions at t3 and t4 (values in t4 were collected on 26 patients)

- -

- Differences between aesthetic dissatisfaction of smokers and non-smokers patients (at t0 and t1)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aoba, T.; Fejerskov, O. Dental fluorosis: Chemistry and biology. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2002, 13, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DenBesten, P.K. Biological mechanisms of dental fluorosis relevant to the use of fluoride supplements. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1999, 27, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.T.; Chen, S.C.; Hall, K.I.; Yamauchi, M.; Bawden, J.W. Protein characterization of fluorosed human enamel. J. Dent. Res. 1996, 75, 1936–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.; Connell, S.; Kirkham, J.; Brookes, S.J.; Shore, R.C.; Smith, A.M. The effect of fluoride on the developing tooth. Caries Res. 2004, 38, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zotti, F.; Laffranchi, L.; Fontana, P.; Dalessandri, D.; Bonetti, S. Effects of fluorotherapy on oral changes caused by a vegan diet. Minerva Stomatol. 2014, 63, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Rezende, K.M.P.C.; Marocho, S.M.S.; Alves, F.B.; Celiberti, P.; Ciamponi, A.L. Dental fluorosis: Exposure, prevention and management. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2009, 1, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, E.Y.; Stenstrom, M.K. Onsite defluoridation system for drinking water treatment using calcium carbonate. J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 216, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, F.; Pietrobelli, A.; Malchiodi, L.; Nocini, P.F.; Albanese, M. Apps for oral hygiene in children 4 to 7 years: Fun and effectiveness. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dhingra, R.; Chaudhuri, P.; Gupta, A. A comparison of various minimally invasive techniques for the removal of dental fluorosis stains in children. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2017, 35, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejerskov, O.; Yaeger, J.A.; Thylstrup, A. Microradiography of the effect of acute and chronic administration of fluoride on human and rat dentine and enamel. Arch. Oral Biol. 1979, 24, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Frechero, N.; Nevarez-Rascón, M.; Nevarez-Rascón, A.; González-González, R.; Irigoyen-Camacho, M.E.; Sánchez-Pérez, L.; López-Verdin, S.; Bologna-Molina, R. Impact of Dental Fluorosis, Socioeconomic Status and Self-Perception in Adolescents Exposed to a High Level of Fluoride in Water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nor, N.A.M. Methods and indices in measuring fluorosis: A review. Arch. Orofac. Sci. 2017, 12, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni, T.; Eliades, T.; Papageorgiou, S.N. Interventions for dental fluorosis: A systematic review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mazur, M.; Westland, S.; Guerra, F.; Corridore, D.; Vichi, M.; Maruotti, A.; Nardi, G.M.; Ottolenghi, L. Objective and subjective aesthetic performance of icon® treatment for enamel hypomineralization lesions in young adolescents: A retrospective single center study. J. Dent. 2018, 68, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tirlet, G.; Chabouis, H.F.; Attal, J.P. Infiltration, a new therapy for masking enamel white spots: A 19-month follow-up case series. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2013, 8, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Li, J.Z.; Zuo, Q.L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, H.; Du, M.Q. Accelerated aging effects on color, microhardness and microstructure of ICON resin infiltration. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 23, 7722–7731. [Google Scholar]

- Laffranchi, L.; Zotti, F.; Bonetti, S.; Dalessandri, D.; Fontana, P. Oral implications of the vegan diet: Observational study. Minerva Stomatol. 2010, 59, 583–591. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira Esteves, C.; De Campos, W.G.; Gallo, R.T.; Ebling Artes, G.; Shimabukuro, N.; Witzel, A.L.; Lemos, C.A. Oral profile of eating disorders patients: Case series. Spec. Care Dentist. 2019, 39, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, D.; Mohamed, A.M.F.S.; Liew, A.K.C. Dentine hypersensitivity-like tooth pain associated with the use of high-dose steroid therapy. J. Conserv. Dent. 2019, 22, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, N.; Endo, Y.; Iikubo, M.; Ishii, T.; Harigae, H.; Aida, J.; Sakamoto, M.; Sasano, T. Dentin hypersensitivity-like tooth pain seen in patients receiving steroid therapy: An exploratory study. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 132, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, C.J.; Kugel, G.; Gerlach, R. A randomized, controlled comparison of two professional dentin desensitizing agents immediately post-treatment and 2 months post-treatment. Am. J. Dent. 2018, 31, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malchiodi, L.; Zotti, F.; Moro, T.; De Santis, D.; Albanese, M. Clinical and Esthetical Evaluation of 79 Lithium Disilicate Multilayered Anterior Veneers with a Medium Follow-Up of 3 Years. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Torlakovic, L.; Olsen, I.; Petzold, C.; Tiainen, H.; Øgaard, B. Clinical color intensity of white spot lesions might be a better predictor of enamel demineralization depth than traditional clinical grading. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2012, 142, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roque-Torres, G.D.; Kwon, S.R.; Oyoyo, U.; Li, Y. Measurement of erosion depth using microcomputed tomography and light microscopy. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2020, 83, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auschill, T.M.; Schmidt, K.E.; Arweiler, N.B. Resin Infiltration for Aesthetic Improvement of Mild to Moderate Fluorosis: A Six-month Follow-up Case Report. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2015, 13, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, M.A.; Arana-Gordillo, L.A.; Gomes, G.M.; Gomes, O.M.; Bombarda, N.H.C.; Reis, A.; Loguercio, A.D. Alternative esthetic management of fluorosis and hypoplasia stains: Blending effect obtained with resin infiltration techniques. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2013, 25, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.B.; Caneppele, T.M.; Masterson, D.; Maia, L.C. Is resin infiltration an effective esthetic treatment for enamel development defects and white spot lesions? A systematic review. J. Dent. 2017, 56, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, Z.; Que, K.; Liu, J.; Sun, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Lou, Y.; Zhao, M. Effects of at-home bleaching and resin infiltration treatments on the aesthetic and psychological status of patients with dental fluorosis: A prospective study. J. Dent. 2019, 91, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, R.; Lipari, F.; Puleio, F.; Alibrandi, A.; Lo Giudice, F.; Tamà, C.; Sazonova, E.; Lo Giudice, G. Spectrophotometric Evaluation of Enamel Color Variation Using Infiltration Resin Treatment of White Spot Lesions at One Year Follow-Up. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Narayanan, R.; Prabhuji, M.L.V.; Paramashivaiah, R.; Bhavikatti, S.K. Low-level Laser Therapy in Combination with Desensitising Agent Reduces Dentin Hypersensitivity in Fluorotic and Non-fluorotic Teeth—A Randomised, Controlled, Double-blind Clinical Trial. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2019, 17, 547–556. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte-Rodrigues, L.; Ramos-Jorge, M.L.; Alves-Duarte, A.C.; Fonseca-Silva, T.; Flores-Mir, C.; Marques, L.S. Oral disorders associated with the experience of verbal bullying among Brazilian school-aged children: A case-control study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, S.; Trivedi, A.; Banda, N.R.; Mishra, N.; Singh, G.; Srivastava, E.; Kulkarni, D. Evaluation of Eruption Pattern and Caries Occurrence among Children Affected with Fluorosis. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2019, 20, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zakizade, M.; Davoudi, A.; Akhavan, A.; Shirban, F. Effect of Resin Infiltration Technique on Improving Surface Hardness of Enamel Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2020, 20, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Features | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 |

| Female | 14 |

| Age-Groups (years) | |

| <20 | 4 |

| 20–30 | 20 |

| 31–40 | 3 |

| 41–50 | 3 |

| Smokers | |

| Yes | 13 |

| Not | 17 |

| t0 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Variables | Spearman’s Coef | Significance (p) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitive Teeth at 72 h | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Pain During Treatment | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| Lesion Dimension at t0 | 0.24 | 0.001 |

| Lesion Dimension at t1 | 0.45 | 0.00001 |

| TSFI * at t0 | 0.57 | 0.00001 |

| TSFI * at t1 | 0.46 | 0.00001 |

| Aesthetic Dissatisfaction | p Values |

|---|---|

| t0–t1 | 0.0001 |

| t1–t2 | 0.0078 |

| t2–t3 | 0.25 |

| t3–t4 | 0.99 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zotti, F.; Albertini, L.; Tomizioli, N.; Capocasale, G.; Albanese, M. Resin Infiltration in Dental Fluorosis Treatment—1-Year Follow-Up. Medicina 2021, 57, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57010022

Zotti F, Albertini L, Tomizioli N, Capocasale G, Albanese M. Resin Infiltration in Dental Fluorosis Treatment—1-Year Follow-Up. Medicina. 2021; 57(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleZotti, Francesca, Luca Albertini, Nicolò Tomizioli, Giorgia Capocasale, and Massimo Albanese. 2021. "Resin Infiltration in Dental Fluorosis Treatment—1-Year Follow-Up" Medicina 57, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57010022

APA StyleZotti, F., Albertini, L., Tomizioli, N., Capocasale, G., & Albanese, M. (2021). Resin Infiltration in Dental Fluorosis Treatment—1-Year Follow-Up. Medicina, 57(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57010022