Can Virtual Assistants Perform Cognitive Assessment in Older Adults? A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

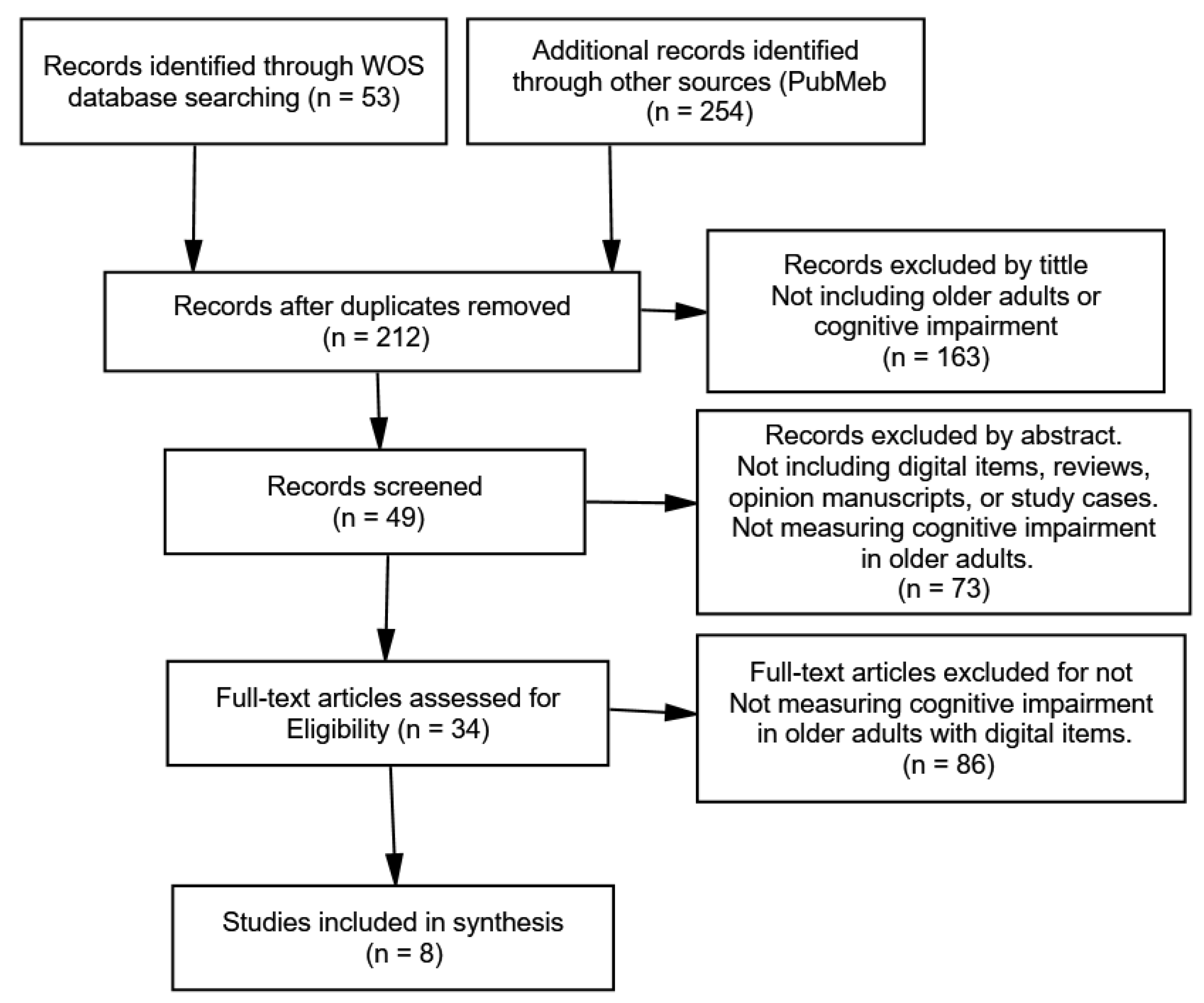

2. Materials and Methods

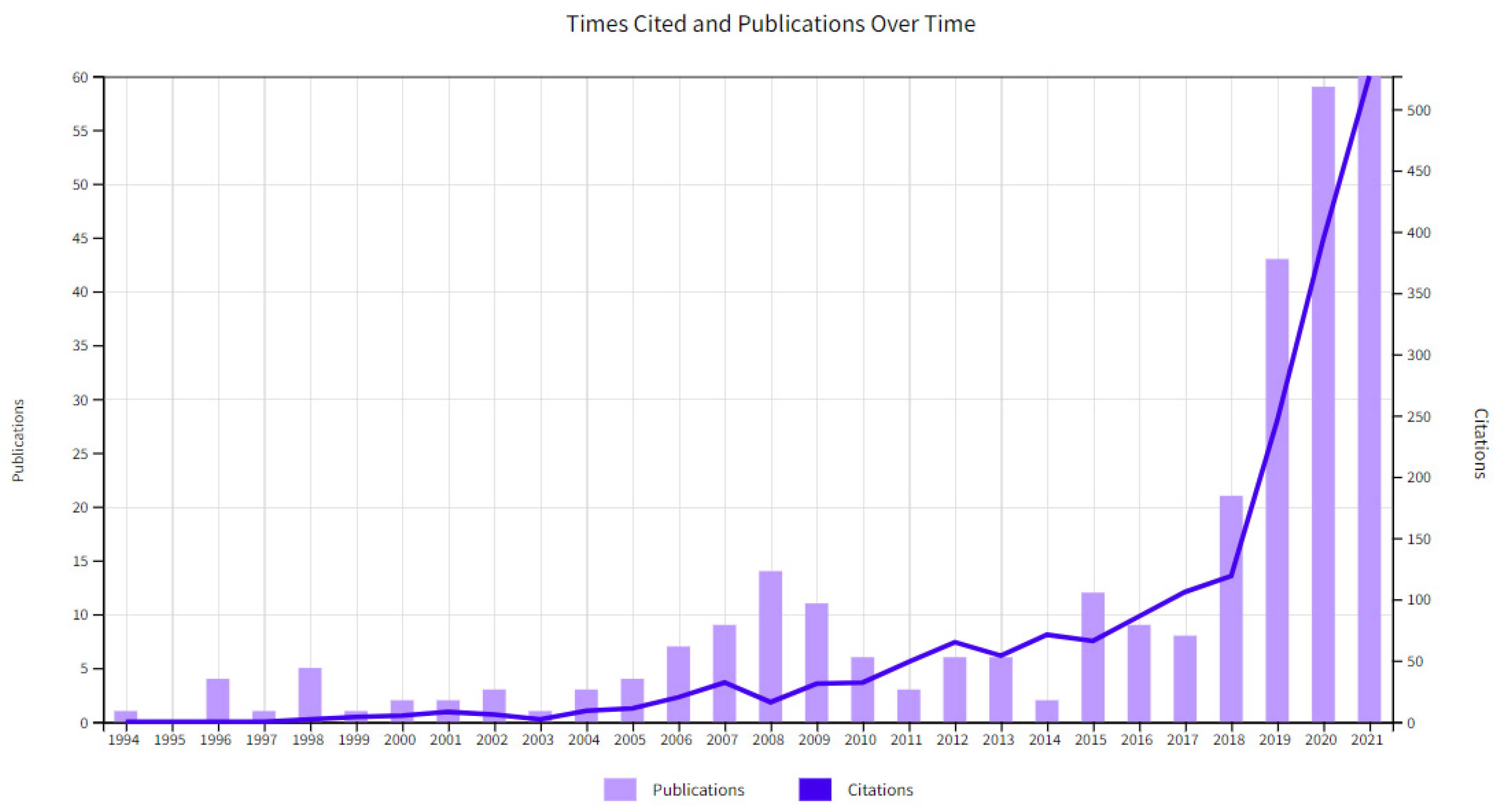

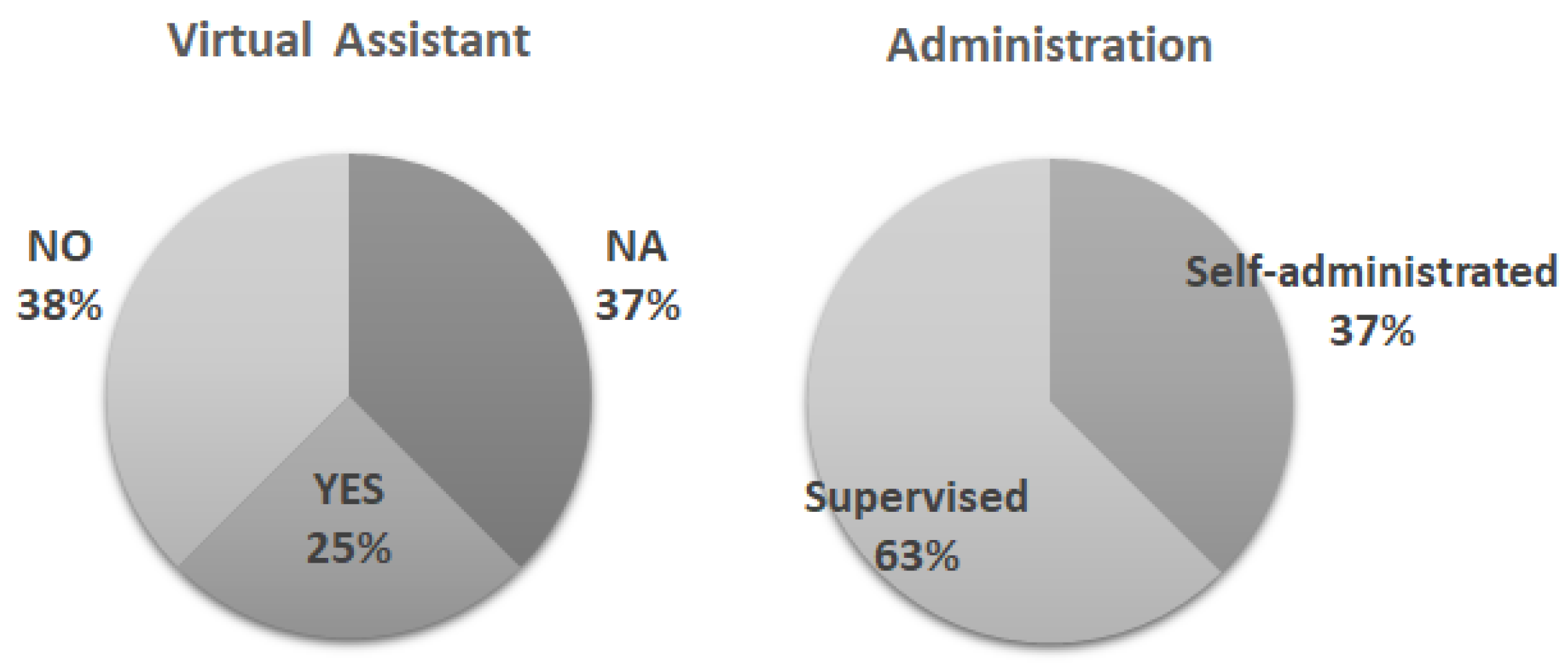

3. Results

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaidyam, A.N.; Wisniewski, H.; Halamka, J.D.; Kashavan, M.S.; Torous, J.B. Chatbots and Conversational Agents in Mental Health: A Review of the Psychiatric Landscape. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchetti, M.; Lee, J.H.; Aschwanden, D.; Sesker, A.; Strickhouser, J.E.; Terracciano, A.; Sutin, A.R. The Trajectory of Loneliness in Response to COVID-19. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. The Growing Problem of Loneliness. Lancet 2018, 391, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palgi, Y.; Shrira, A.; Ring, L.; Bodner, E.; Avidor, S.; Bergman, Y.; Cohen-Fridel, S.; Keisari, S.; Hoffman, Y. The Loneliness Pandemic: Loneliness and Other Concomitants of Depression, Anxiety and Their Comorbidity during the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharani, A.; Pendleton, N.; Leroi, I. Hearing Impairment, Loneliness, Social Isolation, and Cognitive Function: Longitudinal Analysis Using English Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitzner, T.L.; Savla, J.; Boot, W.R.; Sharit, J.; Charness, N.; Czaja, S.J.; Rogers, W.A. Technology Adoption by Older Adults: Findings From the PRISM Trial. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myhre, J.W.; Mehl, M.R.; Glisky, E.L. Cognitive Benefits of Online Social Networking for Healthy Older Adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cotten, S.R.; Ford, G.; Ford, S.; Hale, T.M. Internet Use and Depression Among Retired Older Adults in the United States: A Longitudinal Analysis. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heo, J.; Chun, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J. Internet Use and Well-Being in Older Adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavel, J.J.V.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Nakashima, T. Features of the Japanese National Dementia Strategy in Comparison with International Dementia Policies: How Should a National Dementia Policy Interact with the Public Health- and Social-Care Systems? Alzheimers Dement. 2014, 10, 468–476.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, L.; Wimo, A. The Cost of Dementia in Europe: A Review of the Evidence, and Methodological Considerations. PharmacoEconomics 2009, 27, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr, J.E.; Graham, R.B.; Hofer, S.M.; Muniz-Terrera, G. When does cognitive decline begin? A systematic review of change point studies on accelerated decline in cognitive and neurological outcomes preceding mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and death. Psychol. Aging 2018, 33, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavretsky, H. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Geriatric Psychiatry, 4th ed.; Blazer, D.G., Steffens, D.C., Eds.; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moret-Tatay, C.; Beneyto-Arrojo, M.J.; Gutierrez, E.; Boot, W.R.; Charness, N. A Spanish Adaptation of the Computer and Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaires (CPQ and MDPQ) for Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, N.A.; Boot, W.R. A new tool for assessing mobile device proficiency in older adults: The mobile device proficiency questionnaire. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2018, 37, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampioni, M.; Stara, V.; Felici, E.; Rossi, L.; Paolini, S. Embodied Conversational Agents for Patients With Dementia: Thematic Literature Analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e25381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorodeski, E.Z.; Rosenfeldt, A.B.; Fang, K.; Kubu, C.; Rao, S.M.; Jansen, A.E.; Dey, T.; Alberts, J.L. An iPad-based measure of processing speed in older adults hospitalized for heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 34, E9–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.Y.; Jee, S.J.; Kim, C.S.; Suh, K.S.; Wong, A.W.; Moon, J.Y. The feasibility study of Computer Cognitive Senior Assessment System-Screen (CoSAS-S) in critically ill patients with sepsis. J. Crit. Care 2018, 44, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardini, F.; Luperto, M.; Romeo, M.; Basilico, N.; Daniele, K.; Azzolino, D.; Damanti, S.; Abbate, C.; Mari, D.; Cesari, M.; et al. Supervised digital neuropsychological tests for cognitive decline in older adults: Usability and clinical validity study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Á.; Martin, J.; Jarke, H.; Ruggeri, K. Getting closer? Differences remain in neuropsychological assessments converted to mobile devices. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Park, H.; Doi, T.; Yoshida, D.; Uemura, K.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Suzuki, T. Evaluation of multidimensional neurocognitive function using a tablet personal computer: Test–retest reliability and validity in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoda, K.; Hamano, T.; Nabika, Y.; Aoyama, A.; Takayoshi, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Ishihara, M.; Mitaki, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Oguro, H.; et al. Validation of a new mass screening tool for cognitive impairment: Cognitive Assessment for Dementia, iPad version. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Snowdon, A.; Hussein, A.; Kent, R.; Pino, L.; Hachinski, V. Comparison of an electronic and paper-based Montreal Cognitive Assessment Tool. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2015, 29, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, S.E.; Brown, E.V.D.; Fairman, A.D.; Beardshall, K.; Olexsovich, A.; Taylor, A.; Schreiber, J.B. Validation of the standardized touchscreen assessment of cognition with neurotypical adults. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 40, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampieri, M.; Preslav, N.; Yves, S. Natural language processing for similar languages, varieties, and dialects: A survey. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2020, 26, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, C.S.; Oliveira, C.R.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Navarro-Pardo, E.; De Carli, G.A.; Silva, I.G.; Irigaray, T.; Argimon, I.I.D.L. Phonemic and semantic verbal fluency tasks: Normative data for elderly Brazilians. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2015, 28, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beltrami, D.; Gagliardi, G.; Favretti, R.R.; Ghidoni, E.; Tamburini, F.; Calzà, L. Speech Analysis by Natural Language Processing Techniques: A Possible Tool for Very Early Detection of Cognitive Decline? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrard, P. The effects of very early Alzheimer’s disease on the characteristics of writing by a renowned author. Brain 2004, 128, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Stephan, Y.; Terracciano, A. Verbal fluency and risk of dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Country | Acronym | Tool | Sample | Mean Age | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gorodeski, et al. (2019) [18] | United States | PST | iOS application | 60 | 69 | 4.75 min |

| Kang et al. (2018) [19] | South Korea | CoSAS-S | Tablet-based | 36 | 68 | 10–15 min |

| Lunardini et al., 2020 [20] | Italy | TMT adaptation | web app | 83 | 77.6 | About 2 h after the paper-based tests |

| Maguire et al., 2019 [21] | United States | CNAD-SAGE | iPadOS | 42 | 60.6 | NA |

| Makizato et al. (2013) [22] | United States | NCGG-FAT | iPadOS | 20 | 65–81 | 20–30 |

| Onoda et al., 2013 [23] | Japan | CADi | iPadOS | 222 | 71.73 | 10 min |

| Snowdon et al. (2015) [24] | Canada | eMOCA | a tablet-based | 182 | 51.7 | 15.45 |

| Wallace et al. (2017) [25] | United States | STAC | iPadOS | 88 | 49.18 | 15–30 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moret-Tatay, C.; Iborra-Marmolejo, I.; Jorques-Infante, M.J.; Esteve-Rodrigo, J.V.; Schwanke, C.H.A.; Irigaray, T.Q. Can Virtual Assistants Perform Cognitive Assessment in Older Adults? A Review. Medicina 2021, 57, 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57121310

Moret-Tatay C, Iborra-Marmolejo I, Jorques-Infante MJ, Esteve-Rodrigo JV, Schwanke CHA, Irigaray TQ. Can Virtual Assistants Perform Cognitive Assessment in Older Adults? A Review. Medicina. 2021; 57(12):1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57121310

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoret-Tatay, Carmen, Isabel Iborra-Marmolejo, María José Jorques-Infante, José Vicente Esteve-Rodrigo, Carla H. A. Schwanke, and Tatiana Q. Irigaray. 2021. "Can Virtual Assistants Perform Cognitive Assessment in Older Adults? A Review" Medicina 57, no. 12: 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57121310

APA StyleMoret-Tatay, C., Iborra-Marmolejo, I., Jorques-Infante, M. J., Esteve-Rodrigo, J. V., Schwanke, C. H. A., & Irigaray, T. Q. (2021). Can Virtual Assistants Perform Cognitive Assessment in Older Adults? A Review. Medicina, 57(12), 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57121310